Chapter 6. Securing Online Advertising: Rustlers and Sheriffs in the New Wild West

Read the news of recent computer security guffaws, and it’s striking how many problems stem from online advertising. Advertising is the bedrock of websites that are provided without charge to end users, so advertising is everywhere. But advertising security gaps are equally widespread: from “malvertisement” banner ads pushing rogue anti-spyware software, to click fraud, to spyware and adware, the security lapses of online advertising are striking.

During the past five years, I have uncovered hundreds of online advertising scams defrauding thousands of users—not to mention all the Web’s top merchants. This chapter summarizes some of what I’ve found, and what users and advertisers can do to protect themselves.

Attacks on Users

Users are the first victims—and typically the most direct ones—of online advertising attacks. From deceptive pop-up ads to full-fledged browser exploits, users suffer the direct costs of cleanup. This section looks at some of the culprits.

Exploit-Laden Banner Ads

In March 2004, spam-king-turned-spyware-pusher Sanford Wallace found a way to install software on users’ computers without users’ permission. Wallace turned to security vulnerabilities—defects in Windows, Internet Explorer, or other software on a user’s computer—that let Wallace take control of a user’s computer without the user granting consent. Earlier intruders had to persuade users to click on an executable file or open a virus-infected document—something users were learning to avoid. But Wallace’s new exploit took total control when the user merely visited a website—something we all do dozens of times a day.

Wallace emailed a collaborator to report the achievement:[20]

From: Sanford Wallace, [email protected]

To: Jared Lansky, [email protected]

Subject: I DID IT

Date: March 6, 2004

I figured out a way to install an exe without any user interaction. This is the time to make the $$$ while we can.

Once Wallace got control of a user’s computer via this exploit, he could install any software he chose. A variety of vendors paid Wallace to install their software on users’ computers. So Wallace filled users’ PCs with programs that tracked user behavior, showed pop-up ads, and cluttered browsers with extra toolbars.

But Wallace still had a problem: to take over a user’s computer via a security exploit, Wallace first needed to make the user visit his exploit loader. How? Jared Lansky had an answer: he’d buy advertisements from banner ad networks. Merely by viewing an ad within an ordinary website, a user could get infected with Wallace’s barrage of unwanted software.

Still, buying the advertisement traffic presented major challenges. Few websites sold ads directly to advertisers; instead, most sites sold their ad space through ad networks. But once an ad network realized what was going on, it would be furious. After all, exploits would damage an ad network’s reputation with its affiliated websites.

Wallace and Lansky devised a two-part plan to avoid detection. First, they’d run exploits on the weekend when ad networks were less likely to notice:

From: Sanford Wallace, [email protected]

To: Jared Lansky, [email protected]

Subject: strategy

I do my sneaky shit…today through Sunday—everyone’s off anyway…

Second, if an ad network noticed, Lansky would deny any knowledge of what had happened. For instance, Lansky replied to a complaint from Bob Regular, VP of ad network Cydoor:

From: Jared Lansky, [email protected]

To: Bob Regular, [email protected]

Subject: RE: Please Terminate OptinTrade Online Pharmacy - Violated Agreement

Hi Bob - The pharmacy campaign was a new advertiser with a new code set. When tested it didn’t launch pops or change my homepage so I approved it to run with you. I have no idea how this is happening…

Through this scheme, Wallace and Lansky infected thousands of computers, if not one to two orders of magnitude more. (Litigation documents do not reveal the specifics.) But the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ultimately caught on, bringing suit and demanding repayment of more than $4 million of ill-gotten gains.[21] Unfortunately, Wallace and Lansky’s strategy was just the tip of the iceberg.

Later in 2004, British IT news site The Register[22] was hit by an exploit that installed malware on users’ computers, showed pop ups, tracked user behavior in great detail, and even converted users’ computers into spam-spewing “zombies.” I happened to test that exploit, and found that it installed at least a dozen different programs, totaling hundreds of files and thousands of registry keys.[23] Other such exploits, seen throughout 2005 and 2006, used similar tactics to drop ever-larger payloads.[24]

Visiting even a familiar and respected site could turn a user’s computer into a bot, without the user ever realizing that the trusted site had become a malware factory.

There’s no defending exploit-based software installation: the FTC has repeatedly prohibited nonconsensual installations,[25] and consumer class-action litigation confirmed that nonconsensual installations are a “trespass to chattels”: an interference with a consumer’s use of his private property (here, a computer).[26] So how do exploit-based installers get away with it? For one, they continue the sneakiness of Wallace’s early weekend-only exploits: I’ve seen exploits running only outside business hours, or only for users in certain regions (typically, far from the ad networks that could investigate and take action).

More generally, many exploit-based installers use intermediaries to try to avoid responsibility. Building on Wallace’s partnership with Lansky, these intermediary relationships invoke an often-lengthy series of companies, partners, and affiliates. One conspirator might buy the banner, another runs the exploit, another develops the software, and yet another finds ways to make money from the software. If pressured, each partner would blame another. For example, the company that bought the banner would point out that it didn’t run the exploit, while the company that built the software would produce a contract wherein its distributors promised to get user consent. With so much finger-pointing, conspirators hope to prevent ad networks, regulators, or consumer protection lawyers from figuring out whom to blame.

These attacks are ongoing, but noticeably reduced. What changed? Windows XP Service Pack 2 offers users significantly better protection from exploit-based installs, particularly when combined with post-SP2 patches to Internet Explorer. Also, the financial incentive to run exploits has begun to dry up: regulators and consumers sued the “adware” makers who had funded so many exploit-based installs, and advertisers came to hesitate to advertise through such unpopular pop ups.

For sophisticated readers, it’s possible to uncover these exploits for yourself. Using VMware Workstation, create a fresh virtual machine, and install a vulnerable operating system—for instance, factory-fresh Windows XP with no service packs. Browse the Web and watch for unusual disk or network behavior. Better yet, run a packet sniffer (such as the free Wireshark) and one or more change-trackers. (I like InCtrl for full scans, and HijackThis for quick analysis.) If your computer hits an exploit, examine the packet sniffer logs to figure out what happened and how. Then contact sites, ad networks, and other intermediaries to help get the exploits stopped. I find that I tend to hit exploits most often on entertainment sites—games, song lyrics, links to BitTorrent downloads—but in principle, exploits can occur anywhere. Best of all, after you infect a virtual machine, you can use VMware’s “restore” function to restore the VM’s clean, pre-infection state.

Malvertisements

Unlucky users sometimes encounter banner ads that literally pop out of a web page. In some respects these ads look similar to pop ups, opening a new web browser in addition to the browser the user already opened. But these so-called “malvertisement” ads pop open without the underlying website authorizing any such thing; to the contrary, the website intends to sell an ordinary banner, not a pop up. Furthermore, after these malvertisements pop out of a web page, they typically fill the user’s entire screen, whereas standard pop ups are usually somewhat smaller. Worse, sometimes these malvertisements redirect the user’s entire web browser, entirely replacing the page the user requested and leaving the user with only the unrequested advertisement.

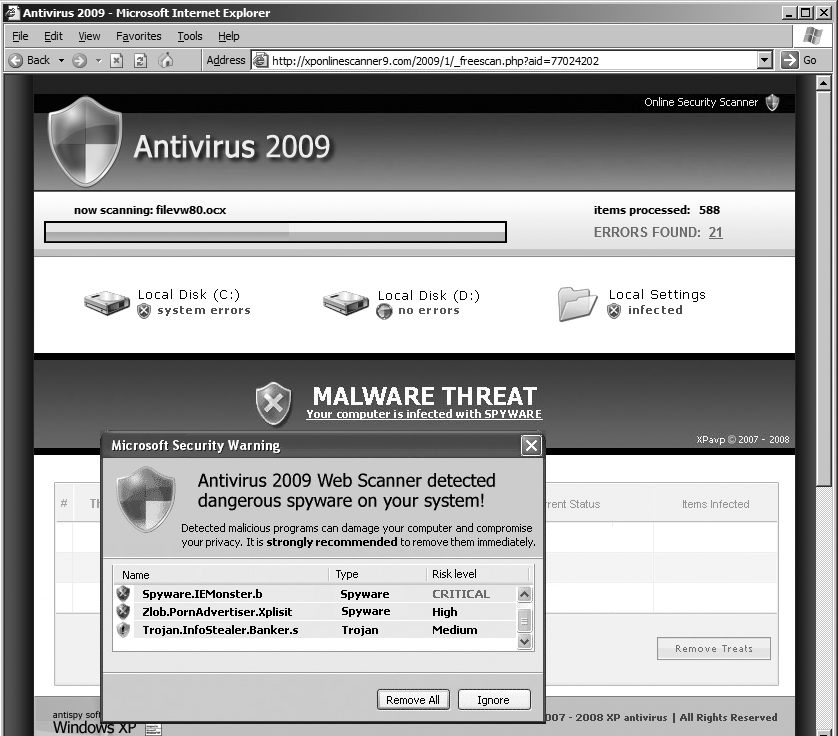

As Figure 6-1 shows, malvertisements typically promote rogue anti-spyware software with claims that a user’s computer is infected with spyware, despite lacking specific evidence that the user’s computer is anything other than normal. For example, the screenshot claims to be “scanning filevw80.ocx”—even though no such file exists on my test PC. Indeed, the pop-up web page is just a web page—not a bona fide scanner, and hence incapable of scanning anything at all. Furthermore, the “now scanning” box is merely part of the advertisement, and even the realistic-looking buttons and icons are all a ruse. But by combining the pop-out interruption with the realistic user interface and the overstated “warning” of infection, these ads can be remarkably effective at getting users’ attention and convincing them to make a purchase.

Malvertisements work hard to avoid detection by websites and ad networks. When viewed in its innocuous state, a malvertisement typically looks like an ordinary Flash ad: a banner, perhaps with limited animation. But when the time is right, the malvertisement uses Flash ActionScript to pop out of the ad frame. How? ActionScript often sports obfuscated code, using a stub procedure to assemble commands decoded from a block of what is, to casual inspection, gibberish. Other ActionScript programs check in with a web server that can consult a user’s IP address and decide how the ad should behave. These systems even detect auditors testing the ad’s behavior by employing remote proxies to adopt a faraway address. Specifically, ActionScript lets an ad obtain the time according to the clock on the user’s PC. If the user’s PC says it’s one time but it’s actually another time at the location associated with the user’s apparent IP address, the ad server can infer that the “user” is a tester connecting by proxy—and the ad server can revert to its innocuous banner mode.

The best defense against these attacks is to fully secure client devices. In the context of typical banner ads, Flash is supposed to show only pictures, animation, and perhaps an occasional video. Why allow such rich code for what is supposed to be just an ad? By default, an ad should have limited permissions, but Flash tends to give ads surprisingly free reign. Unfortunately, a new security model would require fundamental changes to the Flash architecture, meaning action by Adobe, which to date has shown little interest in such defenses.

Fortunately, decentralized development offers two possible ways

forward. First, Flash’s "AllowScriptAccess" tag lets ad networks

disable ad scripts to defend against concealed hostile ads.[27] An ad network need only place this attribute in

the PARAM or EMBED tag that places a Flash banner within a

page. With this attribute in place, the ad can’t invoke outside code, so

attacks are greatly reduced. Some advertisers may insist that their rich

media requires external scripting. But advertisers who have proven their

trustworthiness through their reputation and responsible behavior can

persuade ad networks to let their ads run scripts, while standard or

little-known advertisers get limited permissions to match their limited

reputations.

Alternatively, ad networks can test ads to uncover bad actors. The best-known product in this vein is Right Media’s Media Guard, which uses automated systems to examine ads using a variety of computers in a variety of locations. It’s hard work—serious automation technology that Right Media built at significant expense. But this system lets Right Media feel confident in the behavior of its ads, which becomes crucial as more ad networks exchange inventory through Right Media’s platform. Google now has similar testing, which flags exploits both on advertisers’ pages and in organic search results. But other ad networks, especially small networks, still lack effective tools to catch malicious ads or to ferret them out. That’s too bad for the users who end up caught in the mess created by these networks’ inability to meaningfully assess their advertisers.

Deceptive Advertisements

Thirty years ago, Encyclopædia Britannica sold its wares via door-to-door salesmen who were pushy at best. Knowing that consumers would reject solicitations, Britannica’s salesmen resorted to trickery to get consumers’ attention. In subsequent litigation, a judge described these tactics:

One ploy used to gain entrance into prospects’ homes is the Advertising Research Analysis questionnaire. This form questionnaire is designed to enable the salesman to disguise his role as a salesman and appear as a surveyor engaged in advertising research. [Britannica] fortifies the deception created by the questionnaire with a form letter from its Director of Advertising for use with those prospects who may question the survey role. These questionnaires are thrown away by salesmen without being analyzed for any purpose whatsoever.

The FTC successfully challenged Britannica’s practices,[28] despite Britannica’s appeals all the way to the Supreme Court.[29] The FTC thus established the prohibition on “deceptive door openers” under the principle that once a seller creates a false impression through her initial statements to consumers, the deception may be so serious that subsequent clarifications cannot restore the customer’s capacity for detached judgment. Applying this rule to Britannica’s strategy, the salesman’s claim that he is a research surveyor eviscerates any subsequent consumer “agreement” to buy the encyclopedias—even if the salesman ultimately admits his true role.

Fast-forward to the present, and it’s easy to find online banner ads that are remarkably similar to the FTC’s 1976 Britannica case. One group of sleazy ads asks consumers to answer a shallow survey question (“Do you like George Bush?”), as in Figure 6-2, or to identify a celebrity (“Whose lips are these?”), as in Figure 6-3. Despite the questions, the advertiser doesn’t actually care what users prefer or who users recognize, because the advertiser isn’t really conducting market research. Instead, just as Britannica’s salesmen claimed to conduct “research” simply to get a consumer’s attention, these ads simply want a user to click on a choice so that the advertiser can present users with an entirely unrelated marketing offer.

But “deceptive door opener” ads go beyond survey-type banners. Plenty of other ads make false claims as well. “Get free ringtones,” an ad might promise, even though the ringtones cost $9.99/month—the very opposite of “free” (see Figures 6-4 and 6-5). Or consider an ad promising a “free credit report”—even though the touted service is actually neither free nor a credit report. Other bogus ads try to sell software that’s widely available without charge. Search for “Firefox,” “Skype,” or “Winzip,” and you may stumble into ads attempting to charge for these popular but free programs (see Figure 6-6).

These scams fly in the face of decades of consumer protection law. For one thing, not every clause in an agreement is legally enforceable. In particular, material terms must be clear and conspicuous, not buried in fine print.[30] (For example, the FTC successfully challenged deceptive ads that promised ice cream was “98% fat free” when a footnote admitted the products were not low in fat.[31]) Yet online marketers often think they can promise “free ringtones” or a “free iPod” with a small-type text admitting “details apply.”

Fortunately, regulators are beginning to notice. For example, the FTC challenged ValueClick’s deceptive banners and pop ups, which touted claims like “free PS3 for survey” and “select your free plasma TV.” The FTC found that receiving the promised merchandise required a convoluted and nearly impossible maze of sign-ups and trials. On this basis, the FTC ultimately required ValueClick to pay a $2.9 million fine and to cease such practices.[32] The attorney general of Florida took a similarly negative view of deceptive ringtone ads, including holding ad networks responsible for deceptive ads presented through their systems.[33] Private attorneys are also lending a hand—for example, suing Google for the false ads Google displays with abandon.[34] And in July 2008, the EU Consumer Commissioner reported that more than 80% of ringtone sites had inaccurate pricing, misleading offers, or improper contact information, all bases for legal action.[35] New scam advertisements arise day in and day out, and forward-thinking users should be on the lookout, constantly asking themselves whether an offer is too good to be true. Once suspicious, a user could run a quick web search on a site’s name, perhaps uncovering complaints from others. Or check Whois; scam sites often use privacy protection or far-flung addresses. For automatic assistance, users could look to McAfee SiteAdvisor,[36] which specifically attempts to detect and flag scams.[37]

Are deceptive ads really a matter of “computer security”? While security experts can address some of these shenanigans, consumer protection lawyers can do at least as much to help. But to a user who falls for such tricks, the difference is of limited import. And the same good judgment that protects users from many security threats can also help limit harm from deceptive ads.

Advertisers As Victims

It’s tempting to blame advertisers for all that goes wrong with online advertising. After all, advertisers’ money puts the system in motion. Plus, by designing and buying ads more carefully, advertisers could do much to reduce the harm caused by unsavory advertising practices.

But in some instances, I’m convinced that advertisers end up as victims: they are overcharged by ad networks and get results significantly worse than what they contracted to receive.

False Impressions

In 2006 I examined an online advertising broker called Hula Direct. Hula’s Global-store, Inqwire, and Venus123 sites were striking for their volume of ads: they typically presented at least half a dozen different ad banners on a single page, and sometimes more. Furthermore, Hula often stacked some banners in front of others. As a result, many of the “back” banners would be invisible, covered by an ad further forward in the stack. Users might forgive this barrage of advertising if Hula’s sites interspersed banners among valuable content. But, in fact, Hula’s sites had little real material, just ad after ad. Advertising professionals call these pages “banner farms”: like a farm growing a single crop with nothing else as far as the eye can see, banner farms are effectively just ads.

Industry reports indicated that Hula’s advertisers typically bought ads on a Cost Per Thousand Impressions (CPM) basis. That is, they paid a fee (albeit a small fee, typically a fraction of a cent) for each user who purportedly saw an ad. This payment structure exposes advertisers to a clear risk: if a website like Hula presents their ads en masse, advertisers may end up paying for ads that users were unlikely to notice, click on, or buy from. After all, a page with nothing but banners is unlikely to hold a user’s attention, so an ad there has little hope of getting noticed. An ad at the back of the stack, largely covered by another ad, has no hope at all of being effective (see Figure 6-7).

Hula’s banner farms revealed two further ways to overcharge advertisers. First, Hula loaded ads in pop unders that users never requested. So not only could Hula claim to show many ads, but it could show these ads in low-cost pop-up windows Hula bought from spyware, adware, or low-quality websites. Second, Hula designed its ads to reload themselves as often as every nine seconds. As a result, an advertiser that intended to buy an appearance on a bona fide web page for as long as the user viewed that page would instead get just nine seconds in a Hula-delivered banner farm.[38] Meanwhile, other scammers developed further innovations on the banner farm scam, including loading banners in windows as small as 1×1 pixel each, so that the scammers could get paid even though no ads were actually visible. No wonder advertisers widely view CPM as prone to fraud and hence, all else equal, less desirable than alternative payment metrics.

Escaping Fraud-Prone CPM Advertising

For an advertiser dissatisfied with CPM, online advertising vendors offer two basic alternatives. First, advertisers could pay CPC (cost per click), with fees due only if a user clicks an ad. Alternatively, advertisers could pay CPA (cost per action), where fees are due only if the advertiser actually makes a sale.

At first glance, both these approaches seem less fraud-prone than CPM. Perhaps they’re somewhat better—but experience shows they too can be the basis of troubling scams.

Gaming CPC advertising

CPC advertising is the bedrock of search engines and the source of substantially all of Google’s profit. At its best, CPC lets advertisers reach customers when they’re considering what to buy—potentially an exceptionally effective marketing strategy. But CPC ad campaigns can suffer from striking overcharges.

Consider an independent website publisher that enters into a syndication relationship with a CPC vendor. In such a contract, the CPC vendor pays the publisher a fee—typically a predetermined percentage of the advertiser’s payment—for each advertisement click occurring within the publisher’s site. This creates a natural incentive for the publisher to report extra clicks. How? Some publishers tell their users to click the ads. (“Support my site: Visit one of these advertisers.”) Other publishers use JavaScript to make a user’s browser “click” an ad, regardless of whether the user wants to visit the advertiser.[39] The most sophisticated rogue publishers turn to botnet-type code that causes infected PCs to load a variety of CPC ads—all without a user requesting the ads or, often, even seeing the advertisers’ sites.[40]

CPC advertising is vulnerable to these attacks because its underlying tracking method is easy to trick. Just as a CPM ad network cannot easily determine whether a user actually saw an ad, a CPC vendor often can’t tell whether an ad “click” came from an actual user moving her mouse to an ad and pressing the button, or from some kind of code that faked the click. After all, the CPC vendor tracks clicks based on specially coded HTTP requests sent to the search engine’s web server, bearing the publisher’s ID. But rogue publishers can easily fake these requests without a user actually clicking anything. And in developing countries, there are low-cost services where contractors click ads all day in exchange for payments from the corresponding sites.[41]

For a concerned CPC network, one easy response would be to refuse syndication partnerships, and instead only show ads on its own sites. For example, through mid-2008, Microsoft showed ads only at Live.com, on Microsoft sites, and at sites run by trusted top-tier partners. But this strategy limits the CPC network’s reach, reducing the traffic the network can provide to its advertisers. In contrast, Google chose the opposite tack: in the second quarter of 2008, Google paid its partners fully $1.47 billion to buy ad placements on their sites.[42] This large payment lets Google increase its reach, making its service that much more attractive to prospective advertisers. No wonder Microsoft announced plans in July 2008 to open its syndication more broadly.[43]

CPC vendors claim they have robust methods to identify invalid clicks, including the monitoring of IP addresses, duplicates, and other patterns.[44] But it’s hard to feel confident in their approach. How can CPC vendors know what they don’t catch? And how can CPC vendors defend against a savvy botnet that clicks only a few ads per month per PC, mixes click fraud traffic with genuine traffic, fakes all the right HTTP headers, and even browses a few pages on each advertiser’s site? These fake clicks would easily blend in with bona fide clicks, letting the syndicator claim extra fees with impunity.

In 2005–2006, a series of class actions claimed that top search engines Google, Yahoo!, and others were doing too little to prevent click fraud on credit advertisers’ accounts. The nominal value of settlements passed $100 million, though the real value to advertisers was arguably far less. (If an advertiser didn’t file a claim, its share of the settlement disappeared.) Meanwhile, search engines commissioned self-serving reports denying that click fraud was a major problem.[45] But the fundamental security flaws remained unchanged.

In hopes of protecting themselves from click fraud, advertisers sometimes hire third-party click-fraud detection services to review their web server logfiles in search of suspicious activity.[46] In a widely circulated response, Google mocks some of these services for analytical errors.[47] (Predictably, Google glosses over the extent to which the services’ shortcomings stem from the limited data Google provides to them.) Furthermore, it’s unclear whether a click-fraud detection service could detect botnet-originating click fraud that includes post-click browsing. But whatever the constraints of click-fraud detection services, they at least impose a partial check on overcharges by search engines through success in identifying some clear-cut cases of click fraud.

Inflating CPA costs

Purportedly most resistant to fraud, cost-per-action (CPA) advertising charges an advertiser only if a user makes a purchase from that advertiser’s site. In an important sense, CPA lowers an advertiser’s risk: an advertiser need not pay if no users see the ad, no users click the ad, or no users make a purchase after clicking the ad. So affiliate networks such as LinkShare and Commission Junction tout CPA as a low-risk alternative to other kinds of online advertising.[48]

But CPA is far from immune to fraud. Suppose a merchant were known to pay commissions instantly—say, the same day an order occurs. A co-conspirator could make purchases through an attacker’s CPA link and then return the merchandise for a full refund, yielding instant payment to the attacker, who would keep the commissions even after the return. Alternatively, if declined credit cards or chargebacks take a few days to be noticed, the attacker might be able to abscond with commissions before the merchant notices what happened. This may seem too hard to perpetrate on a large scale, but in fact such scams have turned up (less now than in the past).

In a more sophisticated scheme, an attacker designs a web page or banner ad to invoke CPA links automatically, without a user taking any action to click the link. If the user later happens to make a purchase from the corresponding merchant, the attacker gets paid a commission. Applied to the Web’s largest merchants—Amazon, eBay, and kin—these “stuffed cookies” can quickly yield high commission payouts because many users make purchases from top merchants even without any advertising encouragement.[49] By all indications, the amounts at issue are substantial. For example, eBay considers such fraud serious enough to merit federal litigation, as in eBay’s August 2008 suit against Digital Point Systems and others. In that litigation, eBay claims defendants forced the placement of eBay tracking cookies onto users’ computers, thereby claiming commissions from eBay without providing a bona fide marketing service or, indeed, promoting eBay in any way at all.[50]

In an especially complicated CPA scheme, an attacker first puts tracking software on a user’s computer—spyware or, politely, “adware.” This tracking software then monitors a user’s browsing activity and invokes CPA links to maximize payouts. Suppose an attacker notices that a user is browsing for laptops at Dell’s website. The attacker might then open a CPA link to Dell, so that if the user makes a purchase from Dell, the attacker gets a 2% commission. (After all, where better to find a Dell customer than a user already examining new Dells?) To Dell, things look good: by all indications, a user clicked a CPA link and made a purchase. What Dell doesn’t realize is that the user never actually clicked the link; instead, spyware opened the link. And Dell fails to consider that the user would have purchased the laptop anyway, meaning that the 2% commission payout is entirely unnecessary and completely wasted. Unfortunately, Dell cannot know what really happened, because Dell’s tracking systems tell Dell nothing about what was happening on the user’s computer. Dell cannot identify that the “click” came from spyware rather than a user, and Dell cannot figure out that the user would have made the purchase anyway, without payment of the CPA commission.

During the past four years, I’ve uncovered literally hundreds of bogus CPA affiliates using these tactics.[51] The volume of cheaters ultimately exceeded my capacity to document these incidents manually, so last year I built an automated system to uncover them autonomously. My software browses the Web on a set of spyware-infected virtual machines, watching for any unexpected CPA “click” events, and preserving its findings in packet logs and screen-capture videos.[52] I often now find several new cheaters each day, and I’m not the only one to notice. For example, in class action litigation against ValueClick, merchants are seeking recovery of CPA commissions they shouldn’t have been required to pay.[53] A recently announced settlement creates a $1 million fund for refunds to merchants and to legitimate affiliates whose commissions were lost after attackers overwrote their commission cookies.

Why Don’t Advertisers Fight Harder?

From years of auditing online ad placements, I get the sense that many advertisers don’t view fraud as a priority. Of course, there are exceptions: many small- to medium-sized advertisers cannot tolerate losses to fraud, and some big companies have pervasive commitments to fair and ethical practices. That said, big companies suffer greatly from these practices, yet they tend not to complain.

Marketers often write off advertising fraud as an unavoidable cost of doing business. To me, that puts the cart before the horse. Who’s to say what fraud deserves action and what is just a cost of doing business? By improving the effectiveness of responses to fraud—through finding low-cost ways to identify and prevent it—merchants can transform “unavoidable” losses into a bigger bottom line and a real competitive advantage. Nonetheless, that hasn’t happened often, I believe largely due to the skewed incentives facing advertisers’ staff.

Within companies buying online advertising, individual staff incentives can hinder efforts to protect the company from advertising fraud. Consider an advertising buyer who realizes one of the company’s suppliers has overcharged the company by many thousands of dollars. The company would be best served by the buyer immediately pursuing this matter, probably by bringing it to the attention of in-house counsel or other managers. But in approaching higher-ups, the ad buyer would inevitably be admitting his own historic failure—the fact that he paid the supplier for (say) several months before uncovering the fraud. My discussions with ad buyers convince me that these embarrassment effects are real. Advertising buyers wish they had caught on faster, and they instinctively blame themselves or, in any event, attempt to conceal what went wrong.

Equally seriously, some advertisers compensate ad buyers in ways that discourage ad buyers from rooting out fraud. Consider an ad buyer who is paid 10% of the company’s total online advertising spending. Such an ad buyer has little incentive to reject ads from a bogus source; for every dollar the company spends there, the buyer gets another 10 cents of payment. Such compensation is more widespread than outsiders might expect; many advertisers compensate their outside ad agencies in exactly this way.

For internal ad buyers, incentives can be even more pronounced. For example, a CPA program manager (“affiliate manager”) might be paid $50,000 plus 20% of year-over-year CPA program growth. Expand a program from $500,000 to $800,000 of gross sales, and the manager could earn a nice $60,000 bonus. But if the manager uncovers $50,000 of fraud, that’s effectively a $10,000 reduction in the bonus—tough medicine for even the most dedicated employee. No wonder so many affiliate programs have failed to reject even the most notorious perpetrators.

Similar incentive issues plague the ad networks in their supervision of partners, affiliates, and syndicators. If an ad network admitted that a portion of its traffic was fraudulent, it would need to remove associated charges from its bills to merchants. In contrast, by hiding or denying the problem, the network can keep its fees that much higher. Big problems can’t be hidden forever, but by delaying or downplaying the fraud, ad networks can increase short-term profits.

Lessons from Other Procurement Contexts: The Special Challenges of Online Procurement

When leading companies buy supplies, they typically establish procurement departments with robust internal controls. Consider oversight in the supply chains of top manufacturers: departments of carefully trained staff who evaluate would-be vendors to confirm legitimacy and integrity. In online advertising, firms have developed even larger supply networks—for example, at least hundreds of thousands of sites selling advertising inventory to Google’s AdSense service. Yet advertisers and advertising networks lack any comparable rigor for evaluating publishers.

Indeed, two aspects of online advertising make online advertising procurement harder than procurement in other contexts. First, advertising intermediaries tend to be secretive about where they place ads. Worried that competitors might poach their top partners, networks tend to keep their publisher lists confidential. But as a result, an advertiser buying from (for example) Google AdSense or ValueClick Media cannot know which sites participate. The advertiser thus cannot hand-check partners’ sites to confirm their propriety and legitimacy.

Furthermore, even if a publisher gets caught violating applicable rules, there is typically little to prevent the publisher from reapplying under a new name and URL. Thus, online advertisers have limited ability to block even those wrongdoers they manage to detect. In my paper “Deterring Online Advertising Fraud Through Optimal Payment in Arrears,”[54] I suggest an alternative approach: delaying payment by two to four months so that a publisher faces a financial detriment when its bad acts are revealed. But to date, most advertisers still pay faster than that, letting publishers cheat with little risk of punishment. And advertisers still treat fast payment as a virtue, not realizing that paying too quickly leaves them powerless when fraud is uncovered.

Creating Accountability in Online Advertising

Online advertising remains a “Wild West” where users are faced with ads they ought not to believe and where firms overpay for ads without getting what they were promised in return. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Enforcement by public agencies is starting to remind advertisers and ad networks that long-standing consumer protection rules still apply online. And as advertisers become more sophisticated, they’re less likely to tolerate opaque charges for services they can’t confirm they received.

Meanwhile, the online advertising economy offers exciting opportunities for those with interdisciplinary interests, combining the creativity of a software engineer with the nose-to-the-ground determination of a detective and the public-spiritedness of a civil servant. Do well by doing good—catching bad guys in the process!

[20] These emails were uncovered during FTC litigation, cited in FTC v. Seismic Entertainment, Inc., et al. No. 04-377-JD, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22788 (D.N.H. 2004).

[21] FTC v. Seismic Entertainment, Inc., et al. No. 04-377-JD, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22788 (D.N.H. 2004).

[22] “Bofra Exploit Hits Our Ad Serving Supplier.” The Register. November 21, 2004. http://www.theregister.co.uk/2004/11/21/register_adserver_attack/.

[23] Edelman, Benjamin. “Who Profits from Security Holes?” November 18, 2004. http://www.benedelman.org/news/111804-1.html.

[24] Edelman, Benjamin. “Spyware Installation Methods.” http://www.benedelman.org/spyware/installations/.

[25] See FTC v. Seismic Entertainment, Inc., et al. See also In the Matter of Zango, Inc. f/k/a 180Solutions, Inc., et al. FTC File No. 052 3130. See also In the Matter of DirectRevenue LLC, et al. FTC File No. 052 3131.

[26] Sotelo v. Direct Revenue. 384 F.Supp.2d 1219 (N.D. Ill. 2005).

[27] “Using AllowScriptAccess to Control Outbound Scripting from Macromedia Flash.” http://kb.adobe.com/selfservice/viewContent.do?externalId=tn_16494.

[28] Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 87 F.T.C. 421 (1976).

[29] Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 445 U.S. 934 (1980).

[30] “FTC Advertising Enforcement: Disclosures in Advertising.” http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/workshops/disclosures/cases/index.html.

[31] Häagen-Dazs Co. 119 F.T.C. 762 (1995).

[32] ValueClick, Inc. Case No. CV08-01711 MMM (RZx) (C. Dist. Cal. 2008).

[33] “CyberFraud Task Force.” Office of the Attorney General of Florida. http://myfloridalegal.com/.

[34] Goddard v. Google, Inc. Case No. 108CV111658 (Cal. Super. Ct. 2008).

[35] “EU Crackdown of Ringtone Scams.” EUROPA Memo/08/516. July 17, 2008.

[36] “SiteAdvisor FAQs.” http://www.siteadvisor.com/press/faqs.html.

[37] Disclosure: I am an advisor to McAfee SiteAdvisor. John Viega, editor of this volume, previously led SiteAdvisor’s data team.

[38] Edelman, Benjamin. “Banner Farms in the Crosshairs.” June 12, 2006. http://www.benedelman.org/news/061206-1.html.

[39] Edelman, Benjamin. “The Spyware – Click-Fraud Connection – and Yahoo’s Role Revisited.” April 4, 2006. http://www.benedelman.org/news/040406-1.html.

[40] Daswani, Neil and Stoppelman, Michael. “The Anatomy of Clickbot.A.” Proceedings of the First Workshop on Hot Topics in Understanding Botnets. 2007.

[41] Vidyasagar, N. “India’s Secret Army of Online Ad ‘Clickers.’” The Times of India. May 3, 2004.

[42] Google Form 10-Q, Q2 2008.

[44] See, for example, “How Does Google Detect Invalid Clicks?” https://adwords.google.com/support/bin/answer.py?answer=6114&topic=10625.

[45] See, for example, Tuzhilin, Alexander. “The Lane’s Gifts v. Google Report.” June 21, 2006. http://googleblog.blogspot.com/pdf/Tuzhilin_Report.pdf.

[46] See, for example, Click Defense and Click Forensics.

[47] “How Fictitious Clicks Occur in Third-Party Click Fraud Audit Reports.” August 8, 2006. http://www.google.com/adwords/ReportonThird-PartyClickFraudAuditing.pdf.

[48] See, for example, “pay affiliates only when a sale…is completed” within “LinkShare – Affiliate Information.” http://www.linkshare.com/affiliates/affiliates.shtml.

[49] See, for example, Edelman, Benjamin. “CPA Advertising Fraud: Forced Clicks and Invisible Windows.” http://www.benedelman.org/news/100708-1.html. October 7, 2008.

[50] eBay, Inc. v. Digital Point Solutions, No. 5:08-cv-04052-PVT (N.D. Cal. complaint filed Aug. 25, 2008).

[51] See Edelman, Benjamin. “Auditing Spyware Advertising Fraud: Wasted Spending at VistaPrint.” http://www.benedelman.org/news/093008-1.html. September 30, 2008. See also “Spyware Still Cheating Merchants and Legitimate Affiliates.” http://www.benedelman.org/news/052107-1.html. May 21, 2007. See also “How Affiliate Programs Fund Spyware.” September 14, 2005. http://www.benedelman.org/news/091405-1.html.

[52] Edelman, Benjamin. “Introducing the Automatic Spyware Advertising Tester.” http://www.benedelman.org/news/052107-2.html. May 21, 2007. U.S. patent pending.

[53] Settlement Recovery Center v. ValueClick. Cen. Dis. Calif. No. 2:07-cv-02638-FMC-CTx.

[54] Edelman, Benjamin. “Deterring Online Advertising Fraud Through Optimal Payment in Arrears.” February 19, 2008. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1095262.