10

How Facebook Plays the Long Game

LESSON 8:

Some long games are worth playing if you take care of business in the meantime.

Background: Facebook has been very successful helping people connect—and building related advertising revenue—in many places around the world. Most notably lagging behind those successes are China (Facebook’s services are blocked, and competition is stiff), Japan (competition has kept Facebook from taking a greater share of the lucrative advertising market) and India (only 30% of the population is on the Internet).

Facebook’s Move: Zuckerberg has accepted that overcoming the inherent challenges in China, Japan and India will take time. He is able to pursue these worthwhile but uncertain long games because more essential elements of the business are doing well.

Thought Starter: Are you playing a long game? Is it worth it? How are you thriving in the meantime?

One Step Forward in Cairo, Two Steps Back in Beijing

It’s not hard to imagine the furrowed brows in Beijing in early 2011 as nearly 4,700 miles to the West events were unfolding in Cairo.

Fomented by dissatisfaction with political, economic and human rights conditions, brought to the fore mostly by the younger generation, North Africa and the Middle East experienced a series of internal civil upheavals starting in late 2010. The Arab Spring began in Tunisia, quickly spread to Algeria and Jordan, and then—most publicly—to Egypt where the 30-year reign of Hosni Mubarak came under siege during 18 days of country-wide protests, including as many as 250,000 people in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, that would eventually see the autocrat resign in February 2011, with power transferring to Egypt’s Armed Forces, the parliament being dissolved and the 30-year “emergency law” and national constitution suspended.

Of Egyptians polled after the events, 85% credited social media—particularly Facebook and Twitter—with raising awareness inside the country on the cause of the movements, spreading information to the world about the movement, organizing actions and managing activists.1 Of those surveyed, 95% indicated they used Facebook to get news/information during the civil movements, as opposed to 86% using local, independent or private media and just 48% using regional or international media. Appropriately deflecting credit, Facebook’s leadership would point out that theirs was merely a tool and that change was being brought about not by the platform but by people, one of whom—ironically—was former Google employee Wael Ghonim, who played a leading role in calling for protests in Egypt and was one of the administrators of a Facebook Page titled “We Are All Khaled Saeed” (in memoriam of an Egyptian citizen who had been arrested and later died in custody as a consequence of police brutality in mid-2010), which had hundreds of thousands of followers.

Nevertheless, the connection between social media and large-scale political upheaval with profound consequences had been made to a greater extent than ever before, and by February 2012 rulers had been forced out in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen, uprisings were reaching rarely seen levels in Bahrain and Syria and protests were occurring in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco and Sudan.

Beijing was paying attention. The ability of the Middle East populace—especially the younger contingent—to rise up and throw off its leadership with the help of social platforms, while a “win” for places like Egypt (although the long arc of history continues to be complicated as Mohamed Morsi, democratically elected in June 2012, would be overthrown by the Egyptian military just a year later in July 2013), was a new wave of proof of the most visceral kind that China’s restrictive Internet policies—known in the West as the Great Firewall, which blocks services like Facebook—were precisely appropriate for the goals of the country’s communist government. Whether fundamental instigator or mere organizational tool, these services were not just abstractly incendiary.

Seeing its Middle East ally Mubarak deposed via internal civil pressure—instead of the traditional seen or unseen external political pressure from places like America—was striking, and China took substantial action to avoid “political contagion” between the Middle East and its own population by censoring terms like “Egypt” and “Jasmine” (a flower symbolizing solidarity with Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution) in Internet searches, disallowing the sale of Jasmine flowers, suppressing the efforts of foreign journalists reporting on possible effects of revolutions in the Middle East and detaining human rights advocates including artist Ai Weiwei.

In light of this weighty history and Facebook’s stated mission of making the world more open and connected—arguably the precise opposite of a government intent on controlling information both internally and across borders—success for Zuckerberg in China will be a long and uncertain game, and it is only one of three such efforts in which the Menlo Park company is engaged.

Facebook’s Big Long Game: China

At stake in China for Facebook are the twin pillars of user growth and revenue. Even a 30% penetration—half that of the United States and less than a third that of the Philippines—of the country’s 674 million Internet users would make China Facebook’s largest country by users. And China’s total advertising market is projected to be $67 billion in 2018,2 making a share of the business even just half that of Facebook’s in the United States—about 4.4% in 2015 on $8.3 billion out of $187 billion3—worth $1.5 billion annually with an upside to $2.5 billion when taking into consideration that digital advertising is projected to be nearly 50% of all advertising in China as opposed to the 28% it is projected to be in the United States. At the revenue multiples Facebook was being afforded on Wall Street in the middle of 2016, that could add up to as much as a $40 billion increase in valuation, the same as Twitter, Snapchat and Pinterest combined.

Standing in Facebook’s way are the interconnected forces of censorship and local competition. Blocking has been in place consistently since 2009 for Facebook, Instagram and Messenger (and off-and-on for WhatsApp), while local services—operating under tight rules for user identity, censorship and encryption—are thriving.

While the Chinese constitution affords freedom of speech and press, it allows authorities to crack down on “producing, posting or disseminating pernicious information that may jeopardize state security and disrupt social stability, contravene laws and regulations and spread superstition and obscenity.”4 According to the Council on Foreign Relations, to effect these crackdowns, China’s Golden Shield Project—the actual name of the Great Firewall—has been running since 1998 and engages in bandwidth throttling, keyword filtering (especially around forming collective action, ethnic strife, official corruption, police brutality, the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, freedom of speech, democracy and blocking access) and techniques as basic as shuttering the sites of certain publications, as sophisticated as deep packet inspection and as totalitarian as shutting down the entire Internet as they did for 10 months in 2009 following ethnic riots in the far western Xinjiang province deemed to have been enabled by the Internet. Beyond the digital effort, the government also engages in deterrents like jailing dissident journalists, bloggers and activists; dismissals; demotions; libel lawsuits; fines and forced TV confessions.

To operate in China, services have to carefully balance the country’s mandate to store data on Chinese users in China (where the government has the right to access it whenever they want, as is already the case for American companies such as Apple, Uber and LinkedIn), while assuring existing users outside of China that their data will not leak to the Chinese government and submitting to strict censorship guidelines that are refreshed weekly by the Communist Party Central Propaganda Department and Bureau of Internet Affairs, enforced by more than 100,000 people in state and private employ5 and observed by another 2 million people employed as “opinion analysts” who report on—but do not censor—Internet goings-on.6

Whether you consider these measures draconian or not (France-based watchdog group Reporters Without Borders ranked China 175th out of 180 countries in its 2014 index of press freedom), they are the way of a land carefully managing an information pressure valve between a sense of total oppression on one extreme (think North Korea) and power-altering overthrow on the other (think Tahrir Square). Zuckerberg has made it clear that Facebook—in contrast to Google, which rejected China’s censorship in the early days, subsequently shuttered its China operations and is now slowly crawling back—intends to respect and operate within the system on the way to finding success.

Perhaps more problematic even than censorship, Facebook faces daunting competition—or, for the more cynical, a cocktail of economic protectionism—in building something Chinese users would embrace in addition to wildly popular local products like the messenger WeChat (called Weixin in China where it has more than 600 million users), the micro blogging service Weibo (similar to Twitter, with over 250 million users7) and social network RenRen (most like Facebook, with over 200 million users8), which offer sophisticated takes in connecting people and enabling entertainment and commerce.

Zuckerberg, Sandberg, communications and policy leader Elliott Schrage, veteran corporate and business development vice president Vaughan Smith and Asia Pacific vice president Dan Neary, who has two decades of experience in the region, are well aware of the patience with which they will need to operate to understand China’s politics, economy and people and to deliver a product and business model that fits within that understanding but still exerts some advantage over the dominant incumbents embraced by both the government and hundreds of millions of users.

Zuckerberg has made a point of personal meetings with Xi Jinping, China’s president and general secretary of the Communist Party (said to hold the most consolidated degree of power over China since Mao Zedong), propaganda chief and member of the Communist Party’s Politburo Committee Liu Yunshan, Internet czar Lu Wei and Jack Ma, China’s biggest homegrown entrepreneur and CEO of commerce giant Alibaba. The American’s ability to speak Mandarin, his lectures at Tsinghua University, giving of a Chinese name to daughter Max (Mingyu roughly translates to “bright universe”) and marriage to Priscilla Chan—whose parents are Chinese-Vietnamese refugees who immigrated to the United States—even led state-run television broadcaster China Central Television to dub Zuckerberg “a son-in-law of China.” Sandberg, who as a Disney board member, has had a front-row seat for part of CEO Bob Iger’s 18-year journey—begun under former CEO Michael Eisner—to open Disneyland in Shanghai, is equally sensitized to the opportunity and complexity of landing and operating in China. And Facebook is not starting from scratch in the country. Although it is a little understood beachhead, Facebook already serves the Chinese market with a brisk business selling advertising to companies based in China—from its office in Hong Kong—who are promoting their products (most often mobile apps) elsewhere in the world.

Their effort to land a consumer product in China would be aided—as it has been for so many Western companies now operating in the country—by a partnership with a local company, and local investment via real estate, infrastructure, job creation and revenue sharing. One of the most interesting possibilities on this front would be a partnership with a telecommunications company such as China Telecom with whom Facebook could build telecommunications infrastructure and data centers using its open-sourced Open Compute and Telecom Infrastructure Project technologies and—without the complexities of net neutrality policy it would face in most other countries—offer a differentially priced Internet on-boarding service that brings new awareness and long-term customers (there are still over 500 million unconnected Chinese) to China Telecom and new users to Facebook.

To actually deliver a compelling product, Facebook would need to leverage a unique asset to overcome the advantage of local players. Their best opportunity may be to deliver a modified version of the services it offers elsewhere that asserts their leadership in content from global celebrities, athletes and media companies and combines it with their expertise and technology in mobile video, including live broadcasts. Between Facebook and Instagram—whose contents Facebook could easily combine into one offering—the company has hundreds of sources of content with the most intense global consumer interest, including artists and entertainers (from Beyoncé to The Rock and Vin Diesel to John Cena), athletes and teams (from footballers Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi and Neymar and basketball players LeBron James and Kevin Durant to teams including Manchester United and FC Barcelona), and entertainment (from Disney to MTV and Red Bull to The Simpsons), each with tens of millions of global followers to which these producers are already communicating on a daily basis and who would welcome Facebook’s efforts to extend their reach—especially via video—in China, the second largest economy in the world. While this service would not focus primarily on connections between people, it does offer a unique sense of connection beyond China that people there crave and would be fully stocked with more content than any other source—an archive, possibly even curated, of all the pictures and video previously posted—the day it launched.

As for censorship, in addition to the fact that these sources of content are less likely than the average user to run afoul of China’s censorship due to their own commercial interests with consumers in the country, Facebook could use its advanced artificial intelligence (more on that in Chapter 13) to provide an enhanced ability to affect censorship not just via specific keyword filtering but on the more general meaning of writing, pictures and videos, a technical advance the Chinese government intent on proving its model of Internet sovereignty would likely value and promote as a victory. Enabling the Chinese government with this technology could be seen as a Faustian bargain, but is precisely the kind of complex decision that Zuckerberg will increasingly be faced with given the scale at which he is operating, and the progress or failure that will be at stake.

Other Long Games: Japan and India

Facebook is involved in two other long games also occurring in Asia under the watch of Regional Vice President Dan Neary, but the challenges of the two are different from China and each other.

![]()

At 120 million, Japan’s population is less than a tenth that of China, but its total advertising marketplace is the third most lucrative in the world behind only the United States and China. Projected to total $43 billion by 2018,9 six times as much is spent on advertising per person in Japan as in China and 35 times as much as in India. That makes every additional Japanese user of Facebook’s services very valuable, and although there are 25 million users of Facebook, that is only a 22% share of the 91% of Japanese already on the Internet and not a leadership position. Instagram has 8 million users and is growing quickly, but if patterns from other countries hold true in Japan, the audience has significant overlaps with Facebook rather than being incremental.

Facebook will not only have to contend with digital leaders like local messaging service Line (more than twice as big as Facebook), global Internet video leader YouTube and even Twitter (Japan is one of the few countries where Twitter’s users exceed those of Facebook), but also the complexity of Japan’s advertising business where TV is still the preferred medium at 43% share of the overall business (nearly twice the share of digital) and the ad buying process is controlled nearly monopolistically by powerful local advertising agency Dentsu, which has long-standing agreements with media properties and celebrities and a tight-knit network with Japan’s big advertising spenders. Nevertheless, a doubling of each of Facebook’s user penetration and per-person share of the advertising market in Japan could eventually be worth more than $1 billion annually.

Facebook’s long game in Japan has been underway for many years and will have to continue for many more as no shortcuts are available. They have invested in consumer promotion of Facebook including TV ads and are counting on Instagram to be a powerful boost given how well aligned it is with the aesthetic emphasis in Japanese culture and advertising and that it does not have Facebook’s real name policy, which doesn’t always mesh with a more reserved Japanese culture.

The prize and challenge in India are entirely different from those of Japan. Not a particularly lucrative advertising market (projected to be a total of only $11 billion in 201810), the opportunity in India is instead as a proving ground that Facebook can play a meaningful role in connecting the unconnected. With 1.25 billion inhabitants but only 30% Internet penetration, India is the single biggest incremental Internet connectivity opportunity in the world.

After missteps with internet.org and Free Basics (more in Chapter 14), Facebook will have to reset but can continue to draw on a reservoir of early success—India’s 136 million Facebook users make it the second largest country on Facebook—via rapid introductions of new features and products and the will to make progress. Its remarkably bandwidth-efficient Facebook Lite has already found rapid success among the kind of users who are the next group to connect permanently, and infrastructure technologies meant to further reduce the costs of connectivity, like drones and dedicated satellites being tested in sub-Saharan Africa, will rapidly make their way to India if they show promise. While it may be Facebook’s longest game of all and the one with the heaviest infrastructure lifting, Zuckerberg’s ability to progress against the most fundamental aspect of his mission to make the world more connected is at stake. Expect a special brand of dogged effort.

Which Long Games to Play and When

The farther out one looks, the more options appear to present themselves, especially if you have found a measure of confidence from your early successes. That makes long games the most enticing, least concrete and most dangerous opportunities of all.

With billions of dollars of revenue and as a many as a billion new users of Facebook’s services at stake over the next decade, China, Japan and India are very much long games but occupy a particular spot in the order of Facebook’s priorities: they are dedicated to winning these efforts but can afford to lose without fundamental harm to the business.

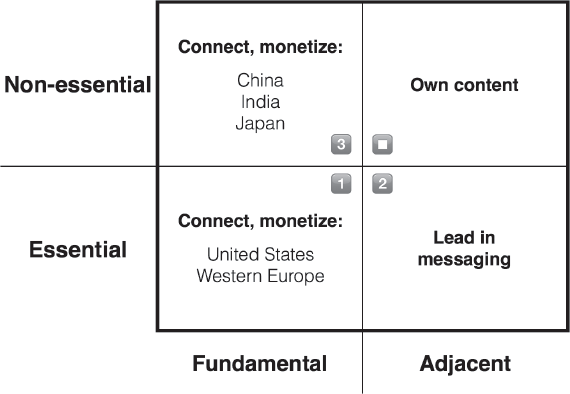

To help make sense of the various kinds of efforts in a business, here is a framework of projects and degrees of criticality to aid in evaluating and planning:

![]() Fundamental projects: The basic expression of your mission

Fundamental projects: The basic expression of your mission

![]() Adjacent projects: A clear—not wishful—expansion of your mission

Adjacent projects: A clear—not wishful—expansion of your mission

![]() Essential: A hill you cannot lose or the one from which competition could attack fatally

Essential: A hill you cannot lose or the one from which competition could attack fatally

![]() Nonessential: Failure does not harm the business fundamentally

Nonessential: Failure does not harm the business fundamentally

Figure 10.1 shows what some of Facebook’s strategy to date looks like in that framing.

Figure 10-1. Framework for evaluating projects for prioritization

The majority of Facebook’s effort, and its highest priority, during Facebook’s first decade were connecting people in the United States and Western Europe and growing advertising revenue relative to those audiences. Connecting existing Internet users in markets accounting for about 50% of global advertising spend11 is both fundamental to Facebook’s mission and essential to its business.

When that effort was on a successful road, Zuckerberg turned his attention to the growing threat of the adjacent messaging market and consolidated the Facebook leadership position with the evolution of the homegrown service Messenger and the very sizable acquisition of WhatsApp (more on that in Chapter 13) in an area clearly adjacent to the core mission and, although not yet broadly lucrative from a revenue perspective, a hill from which others could have attacked Facebook’s core business with dangerous consequences.

Only then did Zuckerberg increase the intensity with which Facebook treated China, Japan and India, but neither to the investment levels of the billions of dollars that had gone into the core of Facebook, Messenger and the acquisition of WhatsApp nor with the same expectations of success. Connecting people in China, Japan and India is certainly fundamental to Zuckerberg’s mission and would bring additional revenue, but the business can survive the uncertainty inherent in these long games with no guarantee of winning.

What Zuckerberg has stayed away from entirely to date are projects that are neither fundamental nor essential. Efforts like owning content (e.g., acquiring the likes of Netflix or Viacom) barely fall within the broadest interpretation of making the world more open and connected and are not essential to a healthy advertising business.

Facebook’s approach to the long game is worth emulating. Don’t be afraid of long games, but take care of the essential part of the business first.