13

Messaging Becomes the Medium

Two more giant apps and an artificial intelligence based on trillions of pieces of data

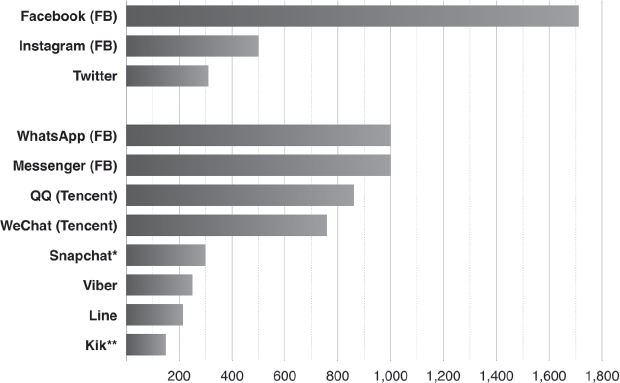

Social media is big. So big that there is only one class of apps bigger: messaging. As you can see in Figure 13-1, while Facebook is the largest social network and Instagram the second largest, there are four messaging apps larger than Instagram: WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Chinese juggernaut Tencent’s QQ and WeChat. A dominant seven of the top 10 communication apps in the world are now messaging apps.

Figure 13-1. Global monthly users (millions, circa Q4 2015 to Q2 2016)1

Is it really possible that the new New Thing™ looks like the old New Thing™—think AOL’s AIM and ICQ—from 20 years ago? It’s not so surprising. Messaging has always been the first and foundational use of every two-way medium:

![]() Telegraph (1844): Samuel Morse’s “What hath God wrought?”

Telegraph (1844): Samuel Morse’s “What hath God wrought?”

![]() Telephone (1876): Alexander Graham Bell’s “Mr. Watson, come here.”

Telephone (1876): Alexander Graham Bell’s “Mr. Watson, come here.”

![]() Internet (1969): Charley Kline’s “lo” (of “login”)

Internet (1969): Charley Kline’s “lo” (of “login”)

Messaging is the original interface. We’ve been talking one-on-one and in small groups for tens of thousands of years, and our modern phones are perfectly suited to expand the pace and scale of that messaging:

![]() Messaging is the simplest, most human, function on our devices.

Messaging is the simplest, most human, function on our devices.

![]() Thanks to your contact list of phone numbers, messaging apps have an instant network of everyone you want to connect with.

Thanks to your contact list of phone numbers, messaging apps have an instant network of everyone you want to connect with.

![]() Everyone is available, all the time, but without the interruption of a phone call.

Everyone is available, all the time, but without the interruption of a phone call.

![]() In addition to bypassing operators’ SMS/MMS fees—especially internationally—many Internet messaging apps also offer voice and video calling.

In addition to bypassing operators’ SMS/MMS fees—especially internationally—many Internet messaging apps also offer voice and video calling.

Because of these simple and powerful benefits, mobile messaging apps can grow quickly. QQ and WeChat (both belonging to Chinese Internet giant Tencent) did so in China, Line is the most popular service in Japan, Viber has a following in Europe and Snapchat is a favorite with U.S. Millennials.

Global leader WhatsApp grew to 400 million monthly active users in just four years. It took Facebook six.

Even following Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram in 2012, it was clear that messaging was going to play a big role in how people shared and which apps were making the world more open and connected, the pursuit Facebook wanted—and needed—to lead. Whether messaging would someday become more prevalent than Facebook itself or simply continue to be adjacent, Zuckerberg needed to protect Facebook against an incursion on its mission while also finding access to additional business opportunities that early efforts by some messaging apps—particularly those in Asia—were beginning to grow to hundreds of millions of dollars.

Zuckerberg needed a dog in the messaging fight.

Dogs in the Fight

While one dog would be good, two would be better. And so begins the story of how the biggest dog of them all, and the one that started as an awkward puppy in Facebook’s own backyard, wound up with the same owner.

It’s not hard to understand where Jan Koum’s low-key, pragmatic style comes from. Koum arrived in Silicon Valley in 1992 as a 16-year-old immigrant from communist Ukraine. He worked at a grocery store, collected food stamps and lived with his mother who suffered from cancer and eventually died in 2000. His father had not been able to come to the United States and died back in Ukraine in 1997.

He would start at San Jose University but leave before finishing his degree to work in infrastructure at Yahoo, where he met Brian Acton who would be a key partner throughout Koum’s career. Disillusioned by the beginning of Yahoo’s decline, the two left in 2007 and cast about for their next jobs, both—ironically—being rejected by Facebook. It was Koum’s first iPhone—and the realization of the power of overlaying your contacts list with a simple and reliable Internet-based status and messaging capability—that drove him and Acton to launch WhatsApp in November 2009.

By early 2012—WhatsApp had 90 million active users—Zuckerberg reached out to Koum, and the two began to have regular meetings. This is the part where the Instagram acquisition and, more importantly, its postacquisition success play a huge role.

As different as the matter-of-fact, under-the-radar Koum and the stylish and public Kevin Systrom are, they are both builders with vision who want a smart partner they’ve learned to trust and the resources and air cover of a successful business, but they also want to be largely left alone to move their products forward.

So when it came time for Koum to consider the $19 billion acquisition—and a Facebook board seat—that Zuckerberg offered in a one-on-one conversation at his house in February 2014 after building the relationship for two years, Koum and Acton would agree.

By February 2016, two years after the acquisition was announced, WhatsApp would grow from 450 million monthly users to 1 billion and send more than 42 billion messages daily—more than double the number of all SMS messages globally—in addition to 1.6 billion photos and 250 million videos. All with a stunningly efficient 57 engineers.

While the story of WhatsApp is meteoric, Facebook Messenger, its home-grown messaging offering, is more of a meandering walkabout to greatness.

Although we’ve been able to send messages within Facebook since its beginnings on the web—something Facebook tried but failed to extend by combining texts, instant messages and e-mail with @facebook.com addresses in November 2010—they did not launch the stand-alone Messenger mobile app until August 2011, a move made possible by the acquisition of iOS and Android group messaging app Beluga earlier that year.

By November 2012, Messenger had grown to only about 57 million monthly users,2 trailing messaging apps like WhatsApp and WeChat, which were rumored to have closer to 200 million users. So Facebook continued its split personality on messaging by integrating some of the best features of stand-alone Messenger back into its main Facebook app to play defense. Messenger continued to grow but by November 2013 was still not a breakout hit, so Facebook reworked the app to be a completely dedicated mobile-to-mobile one-to-one and small-group messenger obsessed with speed and ease of use, including the ability to connect with people based entirely on users’ phone numbers instead of having to be a registered Facebook user—thus mirroring the simple mechanism by which most other large messaging apps made connections.

Six months later, Messenger was still only at 200 million monthly users, and so in April 2014 Facebook made the fateful decision to remove all messaging functionality from its main Facebook app and force people to download Messenger, a controversial move at the time.

Having just made one very big decision regarding Messenger in April, Zuckerberg made another one in May: he would reach out to the president of a 15,000-person company to build a relationship and convince him to come work for him to guide Messenger, a team of just 100 at the time.

David Marcus is a lifelong founder and builder of telecommunications and commerce offerings. In 1996, at age 23, he started GTN Telecom, one of the first telecommunications operators in Switzerland’s deregulated market, and sold it to consolidator World Access in 2000. He then started Echovox, a mobile monetization platform from which he would spin out Zong, a mobile payments company acquired by global Internet payment giant PayPal in 2011. At PayPal he became the leader of mobile and, in 2012, its president.

In short, Marcus was the perfect person to take on the task of building Messenger into something very big now that its is-it-or-isn’t-it-part-of-the-Facebook-app schizophrenia was behind it. The evolution of Instagram and WhatsApp, the opportunity to focus on building the now accelerating Messenger instead of maintaining PayPal and Facebook’s overall growth and business success proved a heady cocktail that Zuckerberg offered up over multiple one-on-one sessions and that eventually Marcus could not resist.

In August 2014, Marcus became the fourth giant builder, along with Instagram’s Kevin Systrom, WhatsApp’s Jan Koum and Oculus VR’s Brendan Iribe, to join Facebook in a period of two and a half years.

It would prove a good decision as the independence of Messenger was paying massive dividends. It grew to 500 million monthly users by November 2014, to 800 million by the end of the following year and to 1 billion by July 2016, giving Facebook not just one but two platforms serving more than 1 billion people in the crucial messaging future.

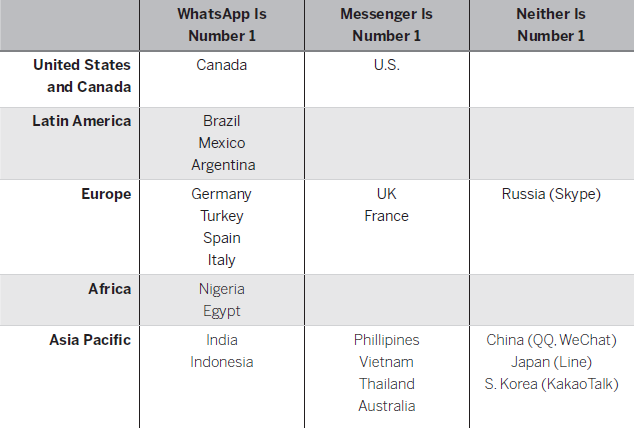

A question that sometimes arises when looking at the two messaging products in Facebook’s stable is whether Zuckerberg really needs both of them. Aside from the two apps creating a belts-and-suspenders hedge in an important space and the strategic flexibility to have Messenger play a pathfinding role in the business aspects of messaging while WhatsApp continues to focus primarily on user growth, it turns out that the two are very complementary when looking at their leadership in the category across some of the biggest Internet countries around the world by the end of 2015. As you can see in Table 13-1, while WhatsApp dominates in Latin America and Africa, Messenger leads in the United States. The two split popularity across European and Asian countries. Only Russia, China, Japan and South Korea have escaped their grasp to date.

Table 13-1. Leading messaging apps around the world

On the Cusp of Something Even Bigger

As big as messaging is, it’s likely a predecessor to something bigger still.

What if messaging were more than messaging? What if instead of just sending messages to people, we could easily include app-like features in our messages (“This is the song I was talking about this morning.”)? What if instead of messaging just with people, we could message with things (“Show me the two best options for European river cruises.”)? What if over time those things could become as intelligent as people and do work on our behalf (“I noticed you were making plans to visit Melanie in Austin next week; here are two restaurants in Austin both of you might like. I can make reservations.”)? What if a group made up of people and intelligent things could converse and get things done together (“We need to pull the data about the best-performing Q2 marketing programs and develop the Q4 plan accordingly.”)? What if this kind of messaging supersedes mobile apps the way mobile apps superseded the web?

What if the graphical user interfaces of the last 30 years were just a stopgap on the way back to the future of the “original” interface: natural language?

An interactive thing participating in messaging is known as a “bot.” The simplest version of this is taking an action you’ve previously done using an app and instead using messaging as a platform to request and deliver that action. These are available today, especially with voice-based interfaces, from some of the biggest Internet players: Apple’s Siri (“What was the score of last night’s Warriors’ game?”), Google’s Now (“What’s next on my calendar?”) and Amazon’s Echo (“Reorder my favorite Keurig cups”).

Already some existing messenger apps like Telegram and Kik for consumers and Slack for business users are acting as platforms that allow other services to plug into their environment to deliver existing services via a messaging interface. Some, like Assist, are building standalone bots to deliver simple services like hailing a ride, getting food delivery, making restaurant reservations and sending flowers. Atlantic Media’s Quartz has built a dedicated app that brings you the news in a messaging-like environment. Others, including Operator and Magic, are using messaging interfaces backed by a combination of software and people to deliver services.

To go much beyond these basic bots will require one of the great evolutions in all of computing: the intelligence, knowledge, history, anticipation and efficiency of a personal assistant. A digital mash-up of beloved Downton Abbey housekeeper Mrs. Hughes and butler Mr. Carson, James Bond boss M’s assistant Ms. Moneypenny and trusty West Winger Mrs. Landingham.

While the wide open and natural way of messaging—say anything—works fantastic for people who are particularly adept at deciphering meaning and applying it to their sophisticated understanding of other people and the world, it is notoriously difficult for computers. It would, however, be an immense force-multiplier for people to get computers involved in working on our behalf without the constrained environments of today’s interfaces—click here, select this, scroll there, enter that, read this—so the best and the brightest press on to evolve these interfaces. To do so, they need to make advances in the broad and complex field of artificial intelligence.

Which means Zuckerberg would need one more big asset beyond two giant messaging platforms to be best positioned for the future: a world-class artificial intelligence lab and an icon to run it.

How fortunate that back in December in 2013 he had recruited—once again via building a relationship and using the scale of Facebook’s mission and the bona fides of Facebook’s existing growth and success of the Instagram integration—pioneering artificial intelligence researcher Yann LeCun. The 55-year-old Frenchman started his path to legend in the early 1990s when he pioneered the use of so-called convolutional neural networks in the field of deep learning. Those fancy words refer to using computers to imitate the way networks of neurons in systems like the human visual cortex work. They are a way for very literal machines to be somewhat abstract. To recognize new things that are similar—but not identical—to many known things that have been given to the computer and internalized at gigantic scale in its preferred language of bits, numbers and math.

Computers may not reason easily, but they are very good at ingesting data and doing math. Given enough data, they can slowly form an understanding of the world. Especially if it’s data like Facebook’s trillions of objects and associations.

The appeal of that data and opportunity to start and lead a team of researchers in California, London, Paris and his native New York while remaining on the faculty at New York University were enough to add LeCun to the mix of great minds at Facebook trying to make the world more open and connected.

LeCun’s research group creates the foundational progress that the applied teams elsewhere at Facebook turn into products for you and me:

![]() Facial recognition: To make it easier to tag your family and friends

Facial recognition: To make it easier to tag your family and friends

![]() Image recognition: To make Facebook more accessible for the vision impaired

Image recognition: To make Facebook more accessible for the vision impaired

![]() Video recognition: To aid in classification—Facebook’s algorithms are smart enough to identify automatically something as obscure as mountain unicycling—and compression

Video recognition: To aid in classification—Facebook’s algorithms are smart enough to identify automatically something as obscure as mountain unicycling—and compression

![]() Language translation: To help you understand your French Canadian friends

Language translation: To help you understand your French Canadian friends

![]() Text analysis: To understand the content, sentiment and meaning of status updates in conjunction with photos and videos and assist the News Feed algorithm in selecting the most relevant content for you

Text analysis: To understand the content, sentiment and meaning of status updates in conjunction with photos and videos and assist the News Feed algorithm in selecting the most relevant content for you

Courtesy of the relentless march of performance improvements—and cost reduction—in computing, as well as the Facebook infrastructure team’s ability to fashion them into powerful digital factories, the most common form of machine intelligence—supervised learning—is reaching a very accomplished stage. The scale and speed at which we can teach computers about language, images and video have made computer recognition commonplace.

So, onward we go to the more complex problems: meaning, reasoning, planning, prediction and remembering. This is the domain of unsupervised learning, something that humans do naturally and literally 24×7 from birth but that is more difficult for computers as it involves constant observation, comprehending relationships between things and the maintenance and constant evolution of lots and lots of memory and understanding.

The difference between supervised learning and unsupervised learning is the difference between understanding a picture and understanding you.

Put more abstractly, Facebook’s computing power is the brain, and all of us the senses of a machine working to understand the world as a whole and each of us individually. What is so pedestrian to people will be the pinnacle for computing: common sense.

That may all seem far-fetched to us in 2017, but just 10 years ago it was equally inconceivable that each of us would carry in our pockets a screen that is connected to everyone and everything we care about. Everywhere. All the time.

When you put all of Facebook’s state-of-the-art-in-2016 assets together—including January 2015 speech recognition acquisition wit.ai—you get the beginnings of something bigger than just a mobile version of AOL Instant Messenger: Facebook M, a virtual assistant that uses the Messenger interface and is backed by artificial intelligence that has—and this is the important part to bridge from today’s capabilities to tomorrow’s—human trainers behind it. Instead of relying just on people, which would never scale to a billion users, or just on computers, which aren’t consistently smart enough yet to take care of things for you by themselves, M’s artificial intelligence will take its best first cut at dealing with your requests, and its human trainers will supervise the work and make the final decisions in handling your requests while the AI observes—and learns. It’s like Training Day for computers. And unlike a real call center where the more people it serves, the worse it gets, with M, the more people it serves, the smarter it gets.

The eventual aim of M is far beyond asking Siri about the weather. It is to use advances in language understanding, vision, prediction and planning to create a Messenger-based digital personal assistant to take care of things for each of us, so we can spend more time on the thing computers cannot do for us: being human.

One Version of the Future: Conversational Interfaces

As we look toward a possible future where messaging platforms are the new browsers (or stores) and bots the new sites (or apps), isn’t there a chance that we are taking three ease-of-use steps back to the cryptic days of “command lines” before graphical user interfaces (GUI) came along? Isn’t the lack of mass adoption of voice-based assistants like Apple’s Siri a sign that even though we can do these things, not enough of us actually will? Aren’t the constraints of a GUI meant to guide us through the few things we can do next, as opposed to overwhelming us with the unlimited possibilities of an empty text entry box? How will I know what that empty box can do unless it can do everything? Is the magic of a digital assistant understanding one request ruined by its inability to understand the next?

To navigate the biggest interface evolution since the arrival of GUIs, we will have to keep the best of the past and bring in the best of what’s now possible: a combination of GUIs and messaging interfaces where you will have the simple back-and-forth, natural language interface you enjoy with other people, and bots—initially backed by people—will respond with graphical, interactive objects contextual to the task you’re completing. We will go through a long transition from highly structured conversations—think the choose-your-own-adventure mechanic of a few options along each step of the conversation—to increasingly free-form interactions, to a truly open conversation with meaning, memory, prediction and anticipation.

All of it following the rapid evolution of unsupervised machine learning backstopped by human trainers until that fateful day when we can finally take the training wheels off and watch bots like M ride into the future by themselves.

Alongside Facebook, other big Internet players in this evolution with the necessary relationship with people—and the data and technology to understand them progressively better—are Google, Amazon (especially in commerce) and Apple (especially in entertainment).

Is There a New Business in This Future?

Definitely. And not just because WeChat’s mobile commerce to order a taxi or pay for a movie or Line’s special business accounts to enable direct messaging with consumers are already making hundreds of millions of dollars.

With Messenger as the lead dog sniffing out opportunities so that WhatsApp can continue to focus on user growth and learn from Messenger’s discoveries, Zuckerberg now has two more assets to create opportunities for people and businesses to connect.

However, finding revenue opportunities that continue the trend of creating value for both people and businesses is not as simple as bringing the Facebook and Instagram advertising experience to messengers since it does not fit the model of one-to-one or small-group messaging.

Instead, it will be communication in a context set by the user (although Facebook ads can be used to encourage people to reach out to businesses via messaging, thus bridging Facebook’s advertising and messaging experiences):

![]() Initial engagement: [Bot] “You have a new meeting in Los Angeles in May. Can we help you with your travel arrangements?”

Initial engagement: [Bot] “You have a new meeting in Los Angeles in May. Can we help you with your travel arrangements?”

![]() Assistance: [You] “I need a better coffee maker than the one in this picture.”

Assistance: [You] “I need a better coffee maker than the one in this picture.”

![]() Transaction: [You] “Order more diapers and the best crib toy for our baby girl.”

Transaction: [You] “Order more diapers and the best crib toy for our baby girl.”

![]() Service: [Bot] “Unfortunately, weather in Denver will cause you to miss your connecting flight, but we have rescheduled you on tomorrow morning’s flight, made reservations at the Marriott and ordered an Uber to take you to the hotel.”

Service: [Bot] “Unfortunately, weather in Denver will cause you to miss your connecting flight, but we have rescheduled you on tomorrow morning’s flight, made reservations at the Marriott and ordered an Uber to take you to the hotel.”

![]() Support: [You] “My dishwasher is broken. Can you send someone?”

Support: [You] “My dishwasher is broken. Can you send someone?”

A new model for handling people’s needs that plays out entirely in a single conversational graphical user interface rather than a convoluted nest of web searches, websites, mobile apps and phone calls. It may take a handful of years to mature—not unlike Facebook’s advertising offering—but we are headed for a future of “agents” that are more powerful and easier to use than their app, website and phone support predecessors.

And as Facebook did for advertising, they will democratize this intelligent messaging over time for every business from the biggest airline to the smallest bakery and for every person with Internet access from the New York business traveler to the Indonesian fisherman expanding their economic network. They will know the most about people, the most about businesses, and provide the best artificial intelligence to assist the two in engaging with each other.

They will deliver Ms. Moneypenny as a service.