11

How Facebook Wins the Talent Wars

LESSON 9:

Employee engagement is everything. Fit to people’s strengths and ignore weaknesses.

Background: With constant connectivity, our jobs have never felt more dangerously pervasive. At the same time, an increasingly service-oriented economy has driven the notion of people being a company’s most important asset to ever greater heights. More than any other single factor, the degree of engagement people have with their company—and their work—affects their contributions and intent to stay.

Facebook’s Move: Facebook puts an emphasis on connecting people to their most engaging work throughout the company, all the way up to its two most important leaders, Zuckerberg and Sandberg.

Thought Starter: When was the last time you asked the people around you what the best part of their day is?

The People Person

In the decade after getting her MBA from Harvard, Lori Goler had shown herself to be what Silicon Valley likes to call an “athlete,” someone with a broad set of abilities in business that have played out in different environments. She had been in business planning at The Walt Disney Company, held general management responsibilities at dotcom-era babystyle.com and led consumer marketing at eBay for five years.

It’s not surprising that when she reached out to Sheryl Sandberg in 2008, she began the call with the very open-ended question, “Sheryl, what is your biggest problem, and can I help solve it?” Sandberg—still in the first few months of her time at Facebook—quickly jumped to the steady stream of incoming talent the company would need in order to live up to its aspirations and asked Goler to come on board to run Recruiting.

It mattered little that Goler had never led a recruiting organization. She had a reputation as a talented exec, was excited about Facebook’s mission and knew that the role mattered a great deal to the company. Just a few months into the job, Chris Cox who led the People team—what other companies call Human Resources—would move to lead the Product team and asked Goler to succeed him, expanding Goler’s responsibilities to HR and Recruiting.

In the eight years since, Goler’s most important contribution to Facebook has been her focus on being a “strengths-based” organization as it went from just a few hundred employees in 2008 to more than 12,000 in 2016, making Facebook and Goler perhaps the largest practitioner of the approach in the world and a consistent winner in the Silicon Valley talent wars.

Anatomy of the Talent Wars

Significant parts of Silicon Valley’s talent wars play out very visibly above the surface in the form of headline-making transitions to Facebook by the likes of Sandberg, consumer marketing head Gary Briggs, advertising business leader David Fischer and leader of newly formed Building 8 skunkworks Regina Dugan (all from Google), Messenger head David Marcus (from PayPal), AI research lab leader Yann LeCun (from academia), and the post-acquisition arrivals of Instagram and WhatsApp CEOs Kevin Systrom and Jan Koum. Other parts play out on smaller stages with lesser-known players who are headhunted, acqui-hired (small acquisitions done primarily to bring on talent) or raise their hand to indicate availability. They may join partially because of the money—if they join early enough—but more so because of the irresistible scope of what they could affect with the things they might build at Facebook (if you’re interested in a dark, borderline vindictive take on that story, read Antonio Garcia Martinez’s soapy 2016 tell-all Chaos Monkeys).

But when you’re hiring thousands of new people a year—all of whom still need to be the best of whoever remains outside of Facebook but don’t rate a headline in TechCrunch, Recode or AdAge—and you can no longer offer world-altering degrees of control or life-altering stock grants, you need an attractor that works for everyone: a reputation for delivering job satisfaction not just for the rock stars but the rank and file.

And hiring is not the most important part. Keeping the 10,000 great employees you already have for as long as you can is the most important part. They are most familiar with what you’re doing and how you’re doing it. Their knowledge and learnings are the hardest to transition and replace. In the exceedingly fortunate economic and intellectual environment of Silicon Valley, which skews younger and, because of its constant creative destruction, values the last few years of your resume above all, the urge to move between opportunities—and the opportunity and encouragement to do so—is extreme. Staying a mere four years—the usual vesting period of initial stock grants that largely control personal outcomes—at one company is common in this twitchy environment. Six years is very good news for your employer, and anything over 10 years is cause for special celebrations. Without the nearly infinitely renewable source of energy that comes from a focus on employee engagement, companies have little chance of being a positive outlier in that distribution.

Attrition, however, is inescapable, so winning the talent wars—and with it your company’s longevity—means winning the inflow vs. outflow equation: are you keeping employees longer than your ever-evolving competition, and are more people coming to you from those competitors than are leaving to join them?

The Inner Game of Employee Engagement

Going back to 1999, Goler had been a fan of Marcus Buckingham’s and Curt Coffman’s management tome First, Break All the Rules. Based on 25 years of Gallup studies of 80,000 managers at 400 companies, the book finds four commonalities among great frontline managers:

1. Select for talent, not just experience or determination.

2. Define outcomes, not steps.

3. Motivate by focusing on strengths, not fixing weaknesses.

4. Find the right fit, not just the next rung.

Numbers 1 and 2 are good, but numbers 3 and 4 most interest Goler: an organizational mindset that focuses on people’s strengths and practically ignores their weaknesses (or, put slightly more pragmatically, works to make weaknesses irrelevant nontalents relative to someone’s role). This focus is a big driver of people’s engagement with their job and company, which in turn is a primary factor in their performance and intent to stay, the preeminent asset in the people economy of Silicon Valley.

Why is Goler so confident in the engagement-centric approach? It comes down to the chemistry of flow and the math of jungle gyms.

While intuitively it seems “nice” to match people’s strengths to their roles in order to maximize engagement, the success of the practice goes much deeper than that. It is rooted in research begun in the 1970s at the University of Chicago by Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Known simply as “flow,” it refers to an optimal state of consciousness where we feel—and perform—our best. It’s so powerful that in a 10-year study conducted by McKinsey, top executives reported being five times more productive in flow.

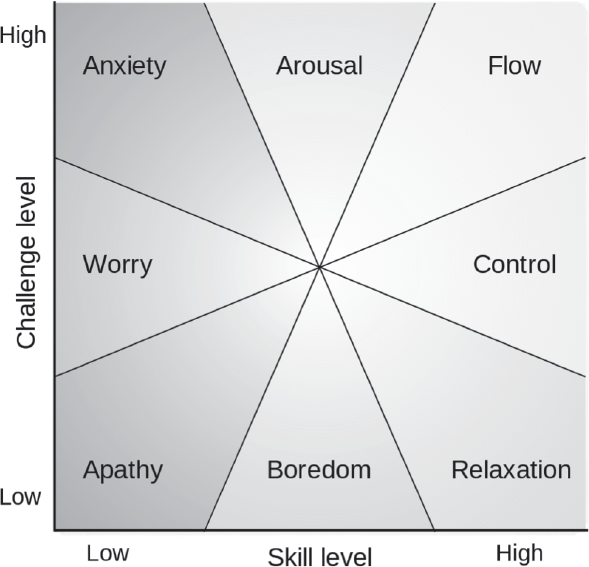

Csikszentmihalyi’s work surfaces a specific approach to understanding how to get into flow and why it is such a powerful state: the flow channel. Depicted in the upper right of Figure 11-1, it relates your skill with a task to the challenge of that task. When you are skilled but not challenged, you are bored. When you are not skilled but highly challenged, you are anxious. When you are neither skilled nor challenged, you are apathetic. In the flow channel, however, you are finely balanced between a constant growth in an existing skill and a level of challenge slightly beyond that skill.

Figure 11-1. Mental states brought about by various combinations of skill and challenge

When in the fine balance of the flow channel, we feel focused, have inner clarity, higher confidence and greater creativity; we learn faster and have a sense of timelessness and high intrinsic motivation. If that sounds suspiciously like an altered state, that’s because it is. Writing in Harvard Business Review in May 2014, Steven Kotler describes the rare confluence of neurochemicals:

In flow, the brain releases norepinephrine, dopamine, endorphins, anandamide, and serotonin. Norepinephrine and dopamine tighten focus, helping us shut out the persistent distractions of our multi-tasked lives. Endorphins block pain, letting us burn the candle at both ends without burning out altogether. Anandamide prompts lateral connections and generates insights far more than most brainstorming sessions. And serotonin, that feel-good chemical . . . bonds teams together more powerfully than the best-intentioned offsite.

These five chemicals are the biggest rewards the brain can produce, and flow is one of the only times the brain produces all five simultaneously. This makes the state one of the most pleasurable, meaningful and—literally—addictive experiences available.

Good stuff, this flow. And having more of it at work is premised on Goler’s focus: connecting people’s strengths with their roles. Flow cannot be induced externally through edict or command. It is virtually impossible to establish without the intrinsic motivation of having your opportunity balanced with your capacity (in the context of clear goals and rapid feedback).

When teams and entire organizations can create these conditions at scale, flow can even exist for the entire system. This sense of group cohesion is known as “social flow,” and at Facebook it stems from the tremendous buy-in to Facebook’s mission of making the world more open and connected at all levels of the company.

In addition to chemistry, there is also math to employee engagement, and it is best captured by contrasting the traditional “career ladder” with Goler’s favorite alternative, the “jungle gym” (her own career has been an example of not only lateral job moves but also steps down such as her original Facebook role).

If a feeling of engagement can be sustained only by constantly being promoted to higher levels of a pyramid with fewer spots at each successive step, the “ladder” makes it a certainty that engagement won’t last for most employees. A “jungle gym,” on the other hand, offers the flexibility of increasing personal development with greater accompanying challenges in one area, as well as the resetting to a new combination of interest, skill and challenge in another.

Put another way, there is simply more room on a jungle gym than on a ladder for everyone to keep flowing.

And that flow has proven crucial to people feeling that they are performing at their best for over 40 years of research across audiences as diverse as surgeons, musicians, dancers, climbers, chess players, Italian farmers, Navajo sheep herders, elderly Korean women, Chicago assembly line workers and Japanese teenage gang members.

It is particularly relevant, however, to Millennials, who will become 44%—the largest part—of the American workforce by 20251 and believe to a much greater degree than Baby Boomers (91% to 71%) that “achieving success and recognition in a career is necessary to living a good life” and will move to the right employer to find the environment for that success (60% of them leave within three years of being hired).2

The implication for the future is simple: engagement that comes from matching skills and challenges isn’t just a nice-to-have for the best companies in the world; it will be impossible to be best without it.

It Works . . . All the Way to the Top

Enough of the theory. Does it work?

Judging by data collected by compensation analysis firm Payscale in 2015 from 33,500 tech workers and published in March 2016, it works very well. Facebook employees were both the most satisfied (96%) and the least stressed (44%) of the 18 top technology companies that were the focus of the study. The next closest company, Google, had less than 90% satisfaction, and technology giant Apple barely more than 70%.

Additionally, Facebook is number 2 (and 1 in Technology), in anonymous job survey site Glassdoor’s “Best Places to Work in 2017” with a rating of 4.5 out of 5 stars, 92% of employees likely to recommend the company to a friend, 92% of employees having a positive outlook for the company’s future and 98% approving of Zuckerberg’s leadership as CEO. Google is 4th. Apple 36th.

Although scoffed at by outsiders, conveniences such as free food, laundry service and shuttle buses have become so common in Silicon Valley that they are no longer the differentiator in the talent wars being waged here every day. A reputation for job satisfaction at a company-wide scale is often now the difference maker, and the reason that Facebook is winning the inflow vs. outflow math of the talent wars.

According to analysis by recruiting site Top Prospect as far back as 2011, Facebook was pulling employees from Apple 11 times more than Apple from Facebook, held a 15:1 advantage over Google and 30:1 over Microsoft. Even in 2015, LinkedIn data examined by Quartz still showed that while Microsoft, Google and Apple were all in the top five former employers of current Facebook employees, Facebook did not appear in the top five list of former employers for Microsoft, Google and Apple employees.

One of the most institutionalized examples of the engagement-focused culture at Facebook is the practice of newly hired engineers selecting their chosen team—as opposed to the other way around—at the conclusion of the company’s six-week Bootcamp that begins every engineer’s time with the company.

Perhaps even more telling, the strengths-based approach plays out all the way to the top of the company, including the division of labor between Zuckerberg (who focuses nearly all his time on product strategy and development) and Sandberg (who is focused on operating the advertising business, partner ecosystems, communications and policy). Zuckerberg spends little time with advertising customers (in contrast to what you would see from more traditionally aligned CEOs), and Sandberg similarly little time on Facebook’s consumer products. These are not signs of disinterest or disrespect for customers or products, respectively, but simply a maximization of the amount of time the duo spends in their areas of strength.

The practice gives Facebook, its employees and its customers the best possible outcomes, and Zuckerberg and Sandberg make for Goler’s best role models for the strengths-based approach, reminding every employee to find their best fit and every manager to play an enabling role in the process.