Chapter 20

Working with Resources

Resources are static bits of information held outside the Java source code. You have seen one type of resource—the layout—frequently in the examples in this book. As you'll learn in this chapter, there are many other types of resources, such as images and strings, that you can take advantage of in your Android applications.

The Resource Lineup

Resources are stored as files under the res/ directory in your Android project layout. With the exception of raw resources (res/raw/), all the other types of resources are parsed for you, either by the Android packaging system or by the Android system on the device or emulator. So, for example, when you lay out an activity's UI via a layout resource (res/layout/), you do not need to parse the layout XML yourself; Android handles that for you.

In addition to layout resources (introduced in Chapter 4) and animation resources (introduced in Chapter 9), several other types of resources are available, including the following:

- Images (

res/drawable/), for putting static icons or other pictures in a user interface - Raw (

res/raw/), for arbitrary files that have meaning to your application but not necessarily to Android frameworks - Strings, colors, arrays, and dimensions (

res/values/), to both give these sorts of constants symbolic names and to keep them separate from the rest of the code (e.g., for internationalization and localization) - XML (

res/xml/), for static XML files containing your own data and structure

String Theory

Keeping your labels and other bits of text outside the main source code of your application is generally considered to be a very good idea. In particular, it helps with internationalization and localization, covered in the “Different Strokes for Different Folks” section later in this chapter. Even if you are not going to translate your strings to other languages, it is easier to make corrections if all the strings are in one spot, instead of scattered throughout your source code.

Android supports regular externalized strings, along with string formats, where the string has placeholders for dynamically inserted information. On top of that, Android supports simple text formatting, called styled text, so you can make your words be bold or italic intermingled with normal text.

Plain Strings

Generally speaking, all you need for plain strings is an XML file in the res/values directory (typically named res/values/strings.xml), with a resources root element, and one child string element for each string you wish to encode as a resource. The string element takes a name attribute, which is the unique name for this string, and a single text element containing the text of the string.

<resources>

<string name="quick">The quick brown fox...</string>

<string name="laughs">He who laughs last...</string>

</resources>

The only tricky part is if the string value contains a quotation mark (") or an apostrophe ('). In those cases, you will want to escape those values, by preceding them with a backslash (e.g., These are the times that try men's souls). Or, if it is just an apostrophe, you could enclose the value in quotation marks (e.g., “These are the times that try men's souls.”).

You can then reference this string from a layout file (as @string/..., where the ellipsis is the unique name, such as @string/laughs). Or you can get the string from your Java code by calling getString() with the resource ID of the string resource, which is the unique name prefixed with R.string. (e.g., getString(R.string.quick)).

String Formats

As with other implementations of the Java language, Android's Dalvik virtual machine supports string formats. Here, the string contains placeholders representing data to be replaced at runtime by variable information (e.g., My name is %1$s). Plain strings stored as resources can be used as string formats:

String strFormat=getString(R.string.my_name);

String strResult=String.format(strFormat, "Tim");

((TextView)findViewById(R.id.some_label)).setText(strResult);

Styled Text

If you want really rich text, you should have raw resources containing HTML, and then pour those into a WebKit widget. However, for light HTML formatting, using <b>, <i>, and <u>, you can just use a string resource. The catch is that you must escape the HTML tags, rather than treating them normally:

<resources>

<string name="b">This has <b>bold</b> in it.</string>

<string name="i">Whereas this has <i>italics</i>!</string>

</resources>

You can access these the same way as you get plain strings, with the exception that the result of the getString() call is really an object supporting the android.text.Spanned interface:

((TextView)findViewById(R.id.another_label))

.setText(getString(R.string.b));

Styled String Formats

Where styled text gets tricky is with styled string formats, as String.format() works on String objects, not Spanned objects with formatting instructions. If you really want to have styled string formats, here is the work-around:

- Entity-escape the angle brackets in the string resource (e.g.,

this is <b>%1$s</b>). - Retrieve the string resource as normal, though it will not be styled at this point (e.g.,

getString(R.string.funky_format)). - Generate the format results, being sure to escape any string values you substitute, in case they contain angle brackets or ampersands.

String.format(getString(R.string.funky_format),htmlEncode

TextUtils.(strName)); - Convert the entity-escaped HTML into a Spanned object via

Html.fromHtml().someTextView.setText(Html

.fromHtml(resultFromStringFormat));

To see this in action, let's look at the Resources/Strings demo. Here is the layout file:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

>

<LinearLayout

android:orientation="horizontal"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

>

<Button android:id="@+id/format"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="@string/btn_name"

/>

<EditText android:id="@+id/name"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

/>

</LinearLayout>

<TextView android:id="@+id/result"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

/>

</LinearLayout>

As you can see, it is just a button, a field, and a label. The idea is for users to enter their name in the field, and then click the button to cause the label to be updated with a formatted message containing their name.

The Button in the layout file references a string resource (@string/btn_name), so we need a string resource file (res/values/strings.xml):

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<resources>

<string name="app_name">StringsDemo</string>

<string name="btn_name">Name:</string>

<string name="funky_format">My name is <b>%1$s</b></string>

</resources>

The app_name resource is automatically created by the activityCreator script. The btn_name string is the caption of the Button, while our styled string format is in funky_format.

Finally, to hook all this together, we need a pinch of Java:

package com.commonsware.android.strings;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.text.TextUtils;

import android.text.Html;

import android.view.View;

import android.widget.Button;

import android.widget.EditText;

import android.widget.TextView;

public class StringsDemo extends Activity {

EditText name;

TextView result;

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle icicle) {

super.onCreate(icicle);

setContentView(R.layout.main);

name=(EditText)findViewById(R.id.name);

result=(TextView)findViewById(R.id.result);

Button btn=(Button)findViewById(R.id.format);

btn.setOnClickListener(new Button.OnClickListener() {

public void onClick(View v) {

applyFormat();

}

});

}

private void applyFormat() {

String format=getString(R.string.funky_format);

String simpleResult=String.format(format,

TextUtils.htmlEncode(name.getText().toString()));

result.setText(Html.fromHtml(simpleResult));

}

}

The string resource manipulation can be found in applyFormat(), which is called when the button is clicked. First, we get our format via getString() (something we could have done at onCreate() time for efficiency). Next, we format the value in the field using this format, getting a String back, since the string resource is in entity-encoded HTML. Note the use of TextUtils.htmlEncode() to entity-encode the entered name, in case someone decides to use an ampersand or something. Finally, we convert the simple HTML into a styled text object via Html.fromHtml() and update our label.

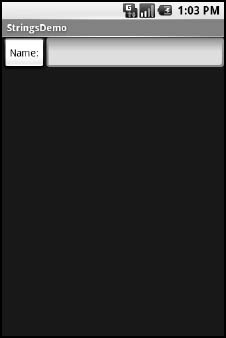

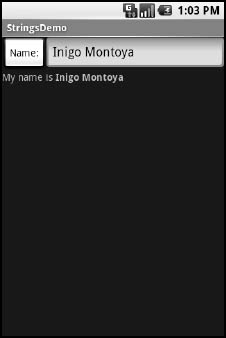

When the activity is first launched, we have an empty label, as shown in Figure 20–1.

Figure 20–1. The StringsDemo sample application, as initially launched

When you fill in a name and click the button, you get the result shown in Figure 20–2.

Figure 20–2. The same application, after filling in some heroic figure's name

Got the Picture?

Android supports images in the PNG, JPEG, and GIF formats. GIF is officially discouraged, however. PNG is the overall preferred format. Images can be used anywhere you require a Drawable, such as the image and background of an ImageView.

Using images is simply a matter of putting your image files in res/drawable/ and then referencing them as a resource. Within layout files, images are referenced as @drawable/... where the ellipsis is the base name of the file (e.g., for res/drawable/foo.png, the resource name is @drawable/foo). In Java, where you need an image resource ID, use R.drawable. plus the base name (e.g., R.drawable.foo).

To demonstrate, let's update the previous example to use an icon for the button instead of the string resource. This can be found as Resources/Images. First, we slightly adjust the layout file, using an ImageButton and referencing a Drawable named @drawable/icon:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

>

<LinearLayout

android:orientation="horizontal"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

>

<ImageButton android:id="@+id/format"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:src="@drawable/icon"

/>

<EditText android:id="@+id/name"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

/>

</LinearLayout>

<TextView android:id="@+id/result"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

/>

</LinearLayout>

Next, we need to put an image file in res/drawable with a base name of icon. In this case, we use a 32-by-32 PNG file from the Nuvola icon set (http://www.icon-king.com/projects/nuvola/). Finally, we twiddle the Java source, replacing our Button with an ImageButton:

package com.commonsware.android.images;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.text.TextUtils;

import android.text.Html;

import android.view.View;

import android.widget.Button;

import android.widget.ImageButton;

import android.widget.EditText;

import android.widget.TextView;

public class ImagesDemo extends Activity {

EditText name;

TextView result;

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle icicle) {

super.onCreate(icicle);

setContentView(R.layout.main);

name=(EditText)findViewById(R.id.name);

result=(TextView)findViewById(R.id.result);

ImageButton btn=(ImageButton)findViewById(R.id.format);

btn.setOnClickListener(new Button.OnClickListener() {

public void onClick(View v) {

applyFormat();

}

});

}

private void applyFormat() {

String format=getString(R.string.funky_format);

String simpleResult=String.format(format,

TextUtils.htmlEncode(name.getText().toString()));

result.setText(Html.fromHtml(simpleResult));

}

}

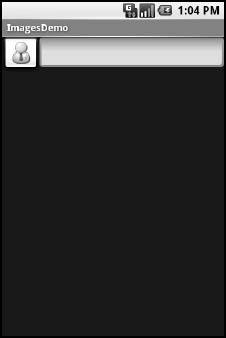

Now, our button has the desired icon, as shown in Figure 20–3.

Figure 20–3. The ImagesDemo sample application

XML: The Resource Way

If you wish to package static XML with your application, you can use an XML resource. Simply put the XML file in res/xml/. Then you can access it by getXml() on a Resources object, supplying it a resource ID of R.xml. plus the base name of your XML file. For example, in an activity, with an XML file of words.xml, you could call getResources().getXml(R.xml.words).

This returns an instance of an XmlPullParser, found in the org.xmlpull.v1 Java namespace. An XML pull parser is event-driven: you keep calling next() on the parser to get the next event, which could be START_TAG, END_TAG, END_DOCUMENT, and so on. On a START_TAG event, you can access the tag's name and attributes; a single TEXT event represents the concatenation of all text nodes that are direct children of this element. By looping, testing, and invoking per-element logic, you parse the file.

To see this in action, let's rewrite the Java code for the Files/Static sample project to use an XML resource. This new project, Resources/XML, requires that you place the words.xml file from Static not in res/raw/, but in res/xml/. The layout stays the same, so all that needs to be replaced is the Java source:

package com.commonsware.android.resources;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.app.ListActivity;

import android.view.View;

import android.widget.AdapterView;

import android.widget.ArrayAdapter;

import android.widget.ListView;

import android.widget.TextView;

import android.widget.Toast;

import java.io.InputStream;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import org.xmlpull.v1.XmlPullParser;

import org.xmlpull.v1.XmlPullParserException;

public class XMLResourceDemo extends ListActivity {

TextView selection;

ArrayList<String> items=new ArrayList<String>();

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle icicle) {

super.onCreate(icicle);

setContentView(R.layout.main);

selection=(TextView)findViewById(R.id.selection);

try {

XmlPullParser xpp=getResources().getXml(R.xml.words);

while (xpp.getEventType()!=XmlPullParser.END_DOCUMENT) {

if (xpp.getEventType()==XmlPullParser.START_TAG) {

if (xpp.getName().equals("word")) {

items.add(xpp.getAttributeValue(0));

}

}

xpp.next();

}

}

catch (Throwable t) {

Toast

.makeText(this, "Request failed: "+t.toString(), 4000)

.show();

}

setListAdapter(new ArrayAdapter<String>(this,

android.R.layout.simple_list_item_1,

items));

}

public void onListItemClick(ListView parent, View v, int position,

long id) {

selection.setText(items.get(position).toString());

}

}

Now, inside our try…catch block, we get our XmlPullParser and loop until the end of the document. If the current event is START_TAG and the name of the element is word (xpp.getName().equals("word")), then we get the one and only attribute, and pop that into our list of items for the selection widget. Since we have complete control over the XML file, it is safe enough to assume there is exactly one attribute. If you are not sure that the XML is properly defined, you might consider checking the attribute count (getAttributeCount()) and the name of the attribute (getAttributeName()) before blindly assuming the 0-index attribute is what you think it is.

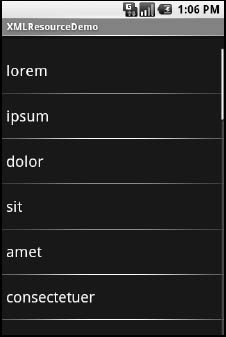

The result looks the same as before, albeit with a different name in the title bar, as shown in Figure 20–4.

Figure 20–4. The XMLResourceDemo sample application

Miscellaneous Values

In the res/values/ directory, in addition to string resources, you can place one (or more) XML files describing other simple resources, such as dimensions, colors, and arrays. You have already seen uses of dimensions and colors in previous examples, where they were passed as simple strings (e.g., “10px”) as parameters to calls. You could set these up as Java static final objects and use their symbolic names, but that works only inside Java source, not in layout XML files. By putting these values in resource XML files, you can reference them from both Java and layouts, plus have them centrally located for easy editing.

Resource XML files have a root element of resources; everything else is a child of that root.

Dimensions

Dimensions are used in several places in Android to describe distances, such a widget's padding. Most of this book's examples use pixels (e.g., 10px for 10 pixels). Several different units of measurement are also available:

inandmmfor inches and millimeters, respectively. These are based on the actual size of the screen.ptfor points. In publishing terms, a point is 1/72 inch (again, based on the actual physical size of the screen).dipandspfor device-independent pixels and scale-independent pixels, respectively. One pixel equals onedipfor a 160-dpi resolution screen, with the ratio scaling based on the actual screen pixel density. Scale-independent pixels also take into account the user's preferred font size.

To encode a dimension as a resource, add a dimen element, with a name attribute for your unique name for this resource, and a single child text element representing the value:

<resources>

<dimen name="thin">10px</dimen>

<dimen name="fat">1in</dimen>

</resources>

In a layout, you can reference dimensions as @dimen/…, where the ellipsis is a placeholder for your unique name for the resource (e.g., thin and fat from the preceding sample). In Java, you reference dimension resources by the unique name prefixed with R.dimen. (e.g., Resources.getDimen(R.dimen.thin)).

Colors

Colors in Android are hexadecimal RGB values, also optionally specifying an alpha channel. You have your choice of single-character hex values or double-character hex values, providing four styles:

#RGB#ARGB#RRGGBB#AARRGGBB

These work similarly to their counterparts in Cascading Style Sheets (CSS).

You can, of course, put these RGB values as string literals in Java source or layout resources. If you wish to turn them into resources, though, all you need to do is add color elements to the resource file, with a name attribute for your unique name for this color, and a single text element containing the RGB value itself:

<resources>

<color name="yellow_orange">#FFD555</color>

<color name="forest_green">#005500</color>

<color name="burnt_umber">#8A3324</color>

</resources>

In a layout, you can reference colors as @color/…, replacing the ellipsis with your unique name for the color (e.g., burnt_umber). In Java, you reference color resources by the unique name prefixed with R.color. (e.g., Resources.getColor(R.color.forest_green)).

Arrays

Array resources are designed to hold lists of simple strings, such as a list of honorifics (Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr., etc.).

In the resource file, you need one string-array element per array, with a name attribute for the unique name you are giving the array. Then add one or more child item elements, each with a single text element containing the value for that entry in the array:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<resources>

<string-array name="cities">

<item>Philadelphia</item>

<item>Pittsburgh</item>

<item>Allentown/Bethlehem</item>

<item>Erie</item>

<item>Reading</item>

<item>Scranton</item>

<item>Lancaster</item>

<item>Altoona</item>

<item>Harrisburg</item>

</string-array>

<string-array name="airport_codes">

<item>PHL</item>

<item>PIT</item>

<item>ABE</item>

<item>ERI</item>

<item>RDG</item>

<item>AVP</item>

<item>LNS</item>

<item>AOO</item>

<item>MDT</item>

</string-array>

</resources>

From your Java code, you can then use Resources.getStringArray() to get a String[] of the items in the list. The parameter to getStringArray() is your unique name for the array, prefixed with R.array. (e.g., Resources.getStringArray(R.array.honorifics)).

Different Strokes for Different Folks

One set of resources may not fit all situations where your application may be used. One obvious area comes with string resources and dealing with internationalization (I18N) and localization (L10N). Putting strings all in one language works fine—at least, for the developer—but covers only one language.

That is not the only scenario where resources might need to differ, though. Here are others:

- Screen orientation: Is the screen in a portrait or landscape orientation? Or is the screen square and, therefore, without an orientation?

- Screen size: How many pixels does the screen have, so you can size your resources accordingly (e.g., large versus small icons)?

- Touchscreen: does the device have a touchscreen? If so, is the touchscreen set up to be used with a stylus or a finger?

- Keyboard: Which keyboard does the user have (QWERTY, numeric, neither), either now or as an option?

- Other input: Does the device have some other form of input, like a D-pad or click-wheel?

The way Android currently handles this is by having multiple resource directories, with the criteria for each embedded in their names.

Suppose, for example, you want to support strings in both English and Spanish. Normally, for a single-language setup, you would put your strings in a file named res/values/strings.xml. To support both English and Spanish, you would create two folders, named res/values-en/ and res/values-es/, where the value after the hyphen is the ISO 639-1 two-letter code for the language. Your English strings would go in res/values-en/strings.xml, and the Spanish ones would go in res/values-es/strings.xml. Android will choose the proper file based on the user's device settings.

An even better approach is for you to consider some language to be your default, and put those strings in res/values/strings.xml. Then create other resource directories for your translations (e.g., res/values-es/strings.xml for Spanish). Android will try to match a specific language set of resources; failing that, it will fall back to the default of res/values/strings.xml.

Seems easy, right?

Where things start to get complicated is when you need to use multiple disparate criteria for your resources. For example, suppose you want to develop both for the T-Mobile G1 and two currently fictitious devices. One device (Fictional One) has a VGA (“large”) screen normally in a landscape orientation, an always-open QWERTY keyboard, a D-pad, but no touchscreen. The other device (Fictional Two) has a G1-sized screen (normal), a numeric keyboard but no QWERTY, a D-pad, and no touchscreen.

You may want to have somewhat different layouts for these devices, to take advantage of different screen real estate and different input options, as follows:

- For each combination of resolution and orientation

- For touchscreen devices versus ones without touchscreens

- For QWERTY versus non-QWERTY devices

Once you get into these sorts of situations, all sorts of rules come into play, such as these:

- The configuration options (e.g.,

-en) have a particular order of precedence, and they must appear in the directory name in that order. The Android documentation outlines the specific order in which these options can appear. For the purposes of this example, screen orientation must precede touchscreen type, which must precede screen size. - There can be only one value of each configuration option category per directory.

- Options are case-sensitive.

So, for the sample scenario, in theory, we would need the following directories:

res/layout-large-port-notouch-qwertyres/layout-normal-port-notouch-qwertyres/layout-large-port-notouch-12keyres/layout-normal-port-notouch-12keyres/layout-large-port-notouch-nokeysres/layout-normal-port-notouch-nokeysres/layout-large-port-stylus-qwertyres/layout-normal-port-stylus-qwertyres/layout-large-port-stylus-12keyres/layout-normal-port-stylus-12keyres/layout-large-port-stylus-nokeysres/layout-normal-port-stylus-nokeysres/layout-large-port-finger-qwertyres/layout-normal-port-finger-qwertyres/layout-large-port-finger-12keyres/layout-normal-port-finger-12keyres/layout-large-port-finger-nokeysres/layout-normal-port-finger-nokeysres/layout-large-land-notouch-qwertyres/layout-normal-land-notouch-qwertyres/layout-large-land-notouch-12keyres/layout-normal-land-notouch-12keyres/layout-large-land-notouch-nokeysres/layout-normal-land-notouch-nokeysres/layout-large-land-stylus-qwertyres/layout-normal-land-stylus-qwertyres/layout-large-land-stylus-12keyres/layout-normal-land-stylus-12keyres/layout-large-land-stylus-nokeysres/layout-normal-land-stylus-nokeysres/layout-large-land-finger-qwertyres/layout-normal-land-finger-qwertyres/layout-large-land-finger-12keyres/layout-normal-land-finger-12keyres/layout-large-land-finger-nokeysres/layout-normal-land-finger-nokeys

Don't panic! We will shorten this list in just a moment.

Note that for many of these, the actual layout files will be identical. For example, we only care about touchscreen layouts being different from the other two layouts, but since we cannot combine those two, we would theoretically need separate directories with identical contents for finger and stylus.

Also note that there is nothing preventing you from having another directory with the unadorned base name (res/layout). In fact, this is probably a good idea, in case future editions of the Android runtime introduce other configuration options you did not consider. Having a default layout might make the difference between your application working or failing on that new device.

Now, we can cheat a bit, by decoding the rules Android uses for determining which, among a set of candidates, is the correct resource directory to use:

- First up, Android tosses out ones that are specifically invalid. So, for example, if the screen size of the device is normal, the

-largedirectories would be dropped as candidates, since they call for some other size. - Next, Android counts the number of matches for each folder, and pays attention to only those with the most matches.

- Finally, Android goes in the order of precedence of the options; in other words, it goes from left to right in the directory name.

So, we could skate by with only the following configurations:

res/layout-large-port-notouch-qwertyres/layout-port-notouch-qwertyres/layout-large-port-notouchres/layout-port-notouchres/layout-large-port-qwertyres/layout-port-qwertyres/layout-large-portres/layout-portres/layout-large-land-notouch-qwertyres/layout-land-notouch-qwertyres/layout-large-land-notouchres/layout-land-notouchres/layout-large-land-qwertyres/layout-land-qwertyres/layout-large-landres/layout-land

Here, we take advantage of the fact that specific matches take precedence over unspecified values. So, a device with a QWERTY keyboard will choose a resource with qwerty in the directory over a resource that does not specify its keyboard type. Combining that with the “most matches wins” rule, we see that res/layout-port will match only devices with normal-sized screens, no QWERTY keyboard, and a touchscreen in portrait orientation.

We could refine this even further, to cover only the specific devices we are targeting (T-Mobile G1, Fictional One, and Fictional Two), plus take advantage of res/layout being the overall default:

res/layout-large-port-notouchres/layout-port-notouchres/layout-large-land-notouchres/layout-land-notouchres/layout-large-landres/layout

Here, -large differentiates Fictional One from the other two devices, while notouch differentiates Fictional Two from the T-Mobile G1.

You will see these resource sets again in Chapter 36, which describes how to support multiple screen sizes.