Chapter 22

Launching Activities and Subactivities

The theory behind the Android UI architecture is that developers should decompose their application into distinct activities. For example, a calendar application could have activities for viewing the calendar, viewing a single event, editing an event (including adding a new one), viewing and editing events on the same screen for larger displays, and so forth. This implies that one of your activities has the means to start up another activity. For example, if a user selects an event from the view-calendar activity, you might want to show the view-event activity for that event. This means that you need to be able to cause the view-event activity to launch and show a specific event (the one the user chose).

This can be further broken down into two scenarios:

- You know which activity you want to launch, probably because it is another activity in your own application.

- You have a content

Urito do something, and you want your users to be able to do something with it, but you do not know up front what the options are.

This chapter covers the first scenario; the second is beyond the scope of this book.

Peers and Subs

One key question you need to answer when you decide to launch an activity is this: does your activity need to know when the launched activity ends?

For example, suppose you want to spawn an activity to collect authentication information for some web service you are connecting to—maybe you need to authenticate with OpenID in order to use an OAuth service. In this case, your main activity will need to know when the authentication is complete so it can start to use the web service.

On the other hand, imagine an e-mail application in Android. When the user elects to view an attachment, neither you nor the user necessarily expects the main activity to know when the user is done viewing that attachment.

In the first scenario, the launched activity is clearly subordinate to the launching activity. In that case, you probably want to launch the child as a subactivity, which means your activity will be notified when the child activity is complete.

In the second scenario, the launched activity is more a peer of your activity, so you probably want to launch the child just as a regular activity. Your activity will not be informed when the child is done, but, then again, your activity really does not need to know.

Start ’Em Up

The two pieces for starting an activity are an intent and your choice of how to start it up.

Make an Intent

As discussed in the previous chapter, intents encapsulate a request, made to Android, for some activity or other receiver to do something. If the activity you intend to launch is one of your own, you may find it simplest to create an explicit intent, naming the component you wish to launch. For example, from within your activity, you could create an intent like this:

new Intent(this, HelpActivity.class);

This stipulates that you want to launch the HelpActivity. This activity would need to be named in your AndroidManifest.xml file, though not necessarily with any intent filter, since you are trying to request it directly.

Or, you could put together an intent for some Uri, requesting a particular action:

Uri uri=Uri.parse("geo:"+lat.toString()+","+lon.toString());

Intent i=new Intent(Intent.ACTION_VIEW, uri);

Here, given that you have the latitude and longitude of some position (lat and lon, respectively) of type Double, you construct a geo scheme Uri and create an intent requesting to view this Uri (ACTION_VIEW).

Make the Call

Once you have your intent, you need to pass it to Android and get the child activity to launch. You have two main options (with a few more advanced/specialized variants):

- The simplest option is to call

startActivity()with theIntent. This will cause Android to find the best-match activity and pass the intent to it for handling. Your activity will not be informed when the child activity is complete. - You can call

startActivityForResult(), passing it theIntentand a number (unique to the calling activity). Android will find the best-match activity and pass the intent to it for handling. Your activity will be notified when the child activity is complete, via theonActivityResult()callback. - In some cases, you may want or need conditional launching, batch launching, etc. of activities. Additional methods like

startActivities(),startActivityFromFragment(), andstartActivityIfNeeded()can help with these cases.

With startActivityForResult(), as noted, you can implement the onActivityResult() callback to be notified when the child activity has completed its work. The callback receives the unique number supplied to startActivityForResult(), so you can determine which child activity is the one that has completed. You also get the following:

- A result code, from the child activity calling

setResult(). Typically, this isRESULT_OKorRESULT_CANCELED, though you can create your own return codes (pick a number starting withRESULT_FIRST_USER). - An optional

Stringcontaining some result data, possibly a URL to some internal or external resource. For example, anACTION_PICKintent typically returns the selected bit of content via this data string. - An optional

Bundlecontaining additional information beyond the result code and data string.

To demonstrate launching a peer activity, take a peek at the Activities/Launch sample application. The XML layout is fairly straightforward: two fields for the latitude and longitude, plus a button.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

>

<TableLayout

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:stretchColumns="1,2"

>

<TableRow>

<TextView

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:paddingLeft="2dip"

android:paddingRight="4dip"

android:text="Location:"

/>

<EditText android:id="@+id/lat"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:cursorVisible="true"

android:editable="true"

android:singleLine="true"

android:layout_weight="1"

/>

<EditText android:id="@+id/lon"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:cursorVisible="true"

android:editable="true"

android:singleLine="true"

android:layout_weight="1"

/>

</TableRow>

</TableLayout>

<Button android:id="@+id/map"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="Show Me!"

android:onClick="showMe"

/>

</LinearLayout>

The button’s showMe() callback method simply takes the latitude and longitude, pours them into a geo scheme Uri, and then starts the activity:

packagecom.commonsware.android.activities;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.content.Intent;

import android.net.Uri;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.View;

import android.widget.EditText;

public class LaunchDemo extends Activity {

private EditText lat;

private EditText lon;

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle icicle) {

super.onCreate(icicle);

setContentView(R.layout.main);

lat=(EditText)findViewById(R.id.lat);

lon=(EditText)findViewById(R.id.lon);

}

public void showMe(View v) {

String _lat=lat.getText().toString();

String _lon=lon.getText().toString();

Uri uri=Uri.parse("geo:"+_lat+","+_lon);

startActivity(new Intent(Intent.ACTION_VIEW, uri));

}

}

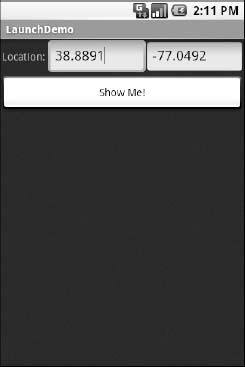

We’ve kept the activity very basic so as to focus on our topic of handling the geo intent. We start as shown in Figure 22–1.

Figure 22–1. The LaunchDemo sample application, with a location filled in

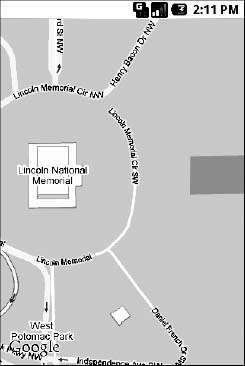

If you fill in a location (e.g., 38.8891 latitude and -77.0492 longitude) and click the button, the resulting map is more interesting, as shown in Figure 22–2. Note that this is the built-in Android map activity—we did not create our own activity to display this map.

Figure 22–2. The map launched by LaunchDemo, showing the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC

In Chapter 40, you will see how you can create maps in your own activities, in case you need greater control over how the map is displayed.

NOTE: This geo:Intent will work only on devices or emulators that have Google Maps installed, or on devices that have some other mapping application that supports the geo: URL.

Tabbed Browsing, Sort Of

One of the main features of the modern desktop web browser is tabbed browsing, where a single browser window can show several pages split across a series of tabs. On a mobile device, this may not make a lot of sense, given that you lose screen real estate for the tabs themselves. In this book, however, we do not let little things like sensibility stop us, so this section demonstrates a tabbed browser, using TabActivity and Intent objects.

As you may recall from the Chapter 14 section “Putting It on My Tab,” a tab can have either a View or an Activity as its content. If you want to use an Activity as the content of a tab, you provide an Intent that will launch the desired Activity; Android’s tab-management framework will then pour the Activity’s UI into the tab.

Your natural instinct might be to use an http: Uri the way we used a geo: Uri in the previous example:

Intent i=new Intent(Intent.ACTION_VIEW);

i.setData(Uri.parse("http://commonsware.com"));

That way, you could use the built-in browser application and get all the features that it offers. Alas, this does not work. You cannot host other applications’ activities in your tabs; only your own activities are allowed, for security reasons. So, we dust off our WebView demos from Chapter 15 and use those instead, repackaged as Activities/IntentTab.

Here is the source to the main activity, the one hosting the TabView:

package com.commonsware.android.intenttab;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.TabActivity;

import android.content.Intent;

import android.net.Uri;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.webkit.WebView;

import android.widget.TabHost;

public class IntentTabDemo extends TabActivity {

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

TabHost host=getTabHost();

Intent i=new Intent(this, CWBrowser.class);

i.putExtra(CWBrowser.URL, "http://commonsware.com");

host.addTab(host.newTabSpec("one")

.setIndicator("CW")

.setContent(i));

i=new Intent(i);

i.putExtra(CWBrowser.URL, "http://www.android.com");

host.addTab(host.newTabSpec("two")

.setIndicator("Android")

.setContent(i));

}

}

As you can see, we are using TabActivity as the base class, and so we do not need our own layout XML—TabActivity supplies it for us. All we do is get access to the TabHost and add two tabs, each specifying an Intent that directly refers to another class. In this case, our two tabs will each host a CWBrowser, with a URL to load supplied via an Intent extra.

The CWBrowser activity is a simple modification to the earlier browser demos:

package com.commonsware.android.intenttab;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.content.Intent;

import android.net.Uri;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.webkit.WebView;

public class CWBrowser extends Activity {

public static final String URL="com.commonsware.android.intenttab.URL";

private WebView browser;

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle icicle) {

super.onCreate(icicle);

browser=new WebView(this);

setContentView(browser);

browser.loadUrl(getIntent().getStringExtra(URL));

}

}

They simply load a different URL into the browser: the CommonsWare home page in one, the Android home page in the other.

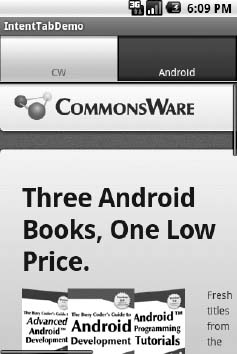

The resulting UI shows what tabbed browsing could look like on Android, as shown in Figures 22–3 and 22–4.

Figure 22–3. The IntentTabDemo sample application, showing the first tab

Figure 22–4. The IntentTabDemo sample application, showing the second tab

However, this approach is rather wasteful. There is a fair bit of overhead in creating an activity that you do not need just to populate tabs in a TabHost. In particular, it increases the amount of stack space needed by your application, and running out of stack space is a significant problem in Android, as will be described in a later chapter.