Knowledge sharing is an ancient and adaptive behavior, but history cautions that the emergence of new ideas—spread through new media—is often resisted by The Powers That Be. That was the case in most organizational cultures until the 20th century when industrialization generated the need for more scientific management practices, which in turn led to more perceptive techniques for internal analysis. Using those techniques, organizations over the past 50 years have identified information handling as the great challenge heading into the 21st century. In this chapter, we describe how knowledge management theory has responded to that challenge and how the subject of this book—online knowledge networking—has developed, since the invention of the computer, as a valuable practice for uncovering and applying knowledge. Throughout the chapter, we provide examples of groundbreaking and current state-of-the-art knowledge networking applications.

As we mentioned at the end of Chapter 1, "Knowledge, History, and the Industrial Organization," some claim that knowledge management is an oxymoron, which Dictionary.com defines as "a rhetorical figure in which incongruous or contradictory terms are combined, as in a deafening silence and a mournful optimist." We're not so sure that knowledge management fully qualifies under that definition, but we recognize the shortcomings of a term that implies that knowledge can be managed.

David Skyrme, a respected British consultant, calls the two words "uneasy bedfellows."1 He points out (and we agree) that real knowledge—based on experience and practice—lives in the human mind and defies external management. Indeed, some say management can kill knowledge, and the history we reviewed in Chapter 1 includes some supporting evidence that kings, pharaohs, and popes have often attempted to suppress the advances that come with new ideas and intellectual exploration.

New knowledge tends to incite change, and entrenched rulers (which include many managers of successful companies) tend to steer clear of adventure, risk, and surprise. Knowledge cannot thrive where its emergence is overcontrolled. But as Skyrme also observes, "knowledge is increasingly recognized as a crucial organizational resource that gives market leverage. Its management is therefore too important to be left to chance." So there must be a happy medium between allowing the wild and random exchange of ideas and opinions and prohibiting any crosstalk among people in the work place. This happy medium can be attained by establishing clear goals and purposes for the exchange and identifying the people who should (and must) be included in the conversation.

A functioning knowledge network does not manage the knowledge. Rather, it manages the structure and composition of the networks that exchange the knowledge. This book provides instruction for building and populating effective online networks that fill an essential role under the broad conceptual umbrella of knowledge management.

The knowledge management approach was originally developed to meet two looming challenges recognized by large businesses as they sought a competitive edge in an expanding and information-intensive marketplace. One was to get a better handle on the runaway growth of useful information by somehow taking control of the sources of that information and not losing information that had been located and captured. The other was to manipulate information to answer vital business questions in an increasingly complex and fast-changing world.

This was the origin of what some call the knowledge as object path. Its goal is to gather key data and configure them in ways that tell the organization how to proceed toward whatever it defines as success. It starts with data collection, storage, and management and applies the searching and parsing skills of virtual librarians and economists to the various data streams associated with purchasing, production, sales, marketing, and human resources.

This path has led to the development of increasingly sophisticated and "intelligent" software platforms—some are called expert systems—that can weave the various data streams together into systems that bring more efficiency to labor-intensive and complex business processes. Today, sophisticated platforms exist for supply chain management, customer-relationship management, hiring, sales forecasting, and resource location, all of which are based on capturing and storing essential information for internal reporting. Suppliers and service providers now employ systems that are compatible with their buyers and clients so that, for example, UPS can interface its delivery system with its customers' supply chain management system, saving time for the customer through greater convenience.

The first waves of knowledge management (KM) theory treated knowledge as content, and the first technologies to implement the theory could best be described as elaborate digital containers and decanters. But just as the cave walls at Chauvet contained information that none of us today can interpret, the information many organizations collect is often beyond the interpretation abilities of their own employees. The tools that store and report the information have to somehow provide (or be used within) a context that gives meaning to the information. Information without context is not truly knowledge.

Treating knowledge as an object—to be captured, stored, and retrieved through intelligent reporting—was (and still is) a powerful lever for organizations, but the approach has practical limitations. It fails to take advantage of the communications capabilities of the Net, and it cannot uncover, store, or distribute the human intelligence possessed by the people in the organization. This intellectual capital is much more fluid and accessible through person-to-person interaction. The facilities of email and online conferencing systems, running on the same digital networks that serve the knowledge-as-object software, allow knowledge sharing to take place on a deeper and more customizable basis.

The management focus of knowledge as process is on people and how they communicate rather than on information and how it is handled. People are more complex and more difficult to manage than information, so it's easy to understand why most organizations have spent more money, time, and resources on developing their capabilities for information handling than on developing those for interpersonal collaboration.

People may be natural knowledge sharers, but within organizations there are competing motivations between loyalty to the organization, loyalty to the team, and loyalty to one's career. There are many different contexts for collaboration depending on the structure of the organization and the task at hand. There are cultural issues, professional issues, and when we're considering online networking, technical competence issues, all of which will be discussed throughout this book.

The knowledge-as-process path is a continuation of the long history of human knowledge sharing. Its leaders and proponents tend to be sociologists, organizational development experts, and anthropologists rather than programmers, executives, and MBAs. Its most enthusiastic participants tend to be the people who actually own the know-how within the organization and who resist the idea that their intellectual assets can be controlled or condensed into pages of data.

Knowledge management was formalized to some degree in the early 1990s, but the roots of both the as-object and as-process paths go back to the very invention of computers and the networks that joined them. The problem recognized then, at the end of World War II, was the same one that prompted the focus on knowledge and information 50 years later.

Only two generations ago the Digital Age was science fiction. The evolution of hardware, software, communications technologies, and interactive techniques is still in its infancy today, but we've come a long way since the idea of storing information and connecting people electronically was conceived, half a century ago. And though we make much of the fact that knowledge networking is an underutilized practice within organizations, the natural tendency for people to want to communicate inspired the earliest visions of what computers could be.

The first description of the modern knowledge network was published on July 1945, at the end of World War II. Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the U.S. government's Office of Scientific Research and Development, wrote an article in Atlantic Monthly titled "As We May Think."[11] He lamented a situation where, in spite of the many great scientific advances that had been made, the organizations of his time were stuck using obsolete methods for dealing with their fast-growing stores of information.

"The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate," he wrote, "and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships." His solution to this outmoded knowledge access situation was an imagined device he called a memex "in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility."

Bush was visualizing the desktop computer. After several generations of technical evolution, the first computer-mediated networks appeared as ARPANET, built by the Advanced Research Project Agency during the 1960s. Initially funded by the Department of Defense, the distributed hub model of ARPANET, in which no single communications node was essential to its operation, was intended to preserve its functionality in case of a nuclear attack. The design proved to be valuable for other reasons, too. It was easy to add nodes, and its nonhierarchical structure encouraged innovation. But the incremental adoption of institutional and academic networking that followed over the next 20 years could only advance the technology so far. These networks were not commercial, and the population using them was very limited. The mainframe computers of the era, which filled large air-conditioned rooms and were accessed through dumb terminals, were prohibitively expensive and slow compared to even the first generation of desktop PCs.

The earliest networks allowed their users to share data files. An operating system named UNIX, which allowed multiple users to share and work simultaneously on files located on a single computer, was invented in 1969. Email was invented in 1971, and many-to-many conferencing through Usenet became a reality in 1979. But these tools served only the relatively few professionals and university-connected users who had access to mainframe computers at the hubs of the various educational and government-sponsored networks that grew out of the ARPANET model. The use of these networks—BITNET and EDUNET were among the most active—served the purposes of scientists and academics seeking to collaborate over a long distance.

Dr. Bush's vision of a personal computer was finally realized in the late 1970s, and with the introduction of the first Apple computers and IBM PCs, commercial multiuser systems like CompuServe, the Source, Genie, and the WELL—all of which relied on modems and telephone dialup connections—introduced new populations of early adopters to the practice of what came to be called virtual community.

A plethora of bulletin board systems (BBSs), each with its own dialup numbers, served the wide range of hobbyists and special interest groups (SIGs) operating from their homes. People paid good money for access to one another's knowledge, and by the late 1980s, the denizens of BBSs and those of the commercial dialup communities discovered each other and began comparing notes on their technologies and cultures.

Connecting people who shared the same interests was the central business proposition of the pre-Web online world. During that time, computer networks were rarely used to support central business processes and internal communications. With few exceptions, computer applications in business were limited to calculating, accounting, and building customer databases, even after the personal computer became commonplace in the office. After all, the software program that most stimulated sales of IBM's first PC was not a communications interface; it was the spreadsheet Lotus 1-2-3.

But almost a decade before the IBM PC, early computer programmers had recognized the possibilities for using their primitive networks to help them improve the software they were writing for nonprogrammers. PLATO was created to share knowledge,[12] but in what we'd think of today as a customer-service application.

Its features and foundation inspired the next generation of collaborative software interfaces. Notes, in its PLATO and Lotus forms, was the idea framework around which other software applications were designed to support teams involved in projects, programming, and design. Peter and Trudy Johnson-Lenz were two inventive researchers who had used and helped design special applications for such software, which they christened groupware.

Groupware was typically categorized along two dimensions:

Whether the members of the group worked together at the same time (real-time or synchronous work)

Whether the members of the group worked together in the same place (collocated or face-to-face) or in different places (noncollocated or distant)

The resulting 2 × 2 matrix described the kinds of software applications and collaboration that were appropriate to the various combinations of time and place.

DIFFERENT TIME | ||

|---|---|---|

Same place | Voting, presentations | Shared computers |

Different place | Chat, videophones | Email, conferencing, workflow |

To help design the software that would fit these various needs and situations, a field of study called Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) developed. The people working in this field represented many different aspects of the work-place experience. According to the Usability First Web site: "The field typically attracts those interested in software design and social and organizational behavior, including business people, computer scientists, organizational psychologists, communications researchers, and anthropologists, among other specialties."[13] The resulting design was more than a mechanistic set of tools to meet the needs of cooperation and work; it was a carefully orchestrated suite of capabilities and options that considered the importance of aspects like competition, socialization, and play.

With the invention of the personal computer, the evolution of design toward greater support of CSCW seemed to reverse itself, but within a short time, the local area network (LAN) was invented to link mainframes, PCs, and computer peripherals as shared resources. Groupware development moved to the local Net. By the late 1980s, LANs could interconnect with the larger geographical networks that were then merging to become what we know as the Internet. The seemingly overnight emergence and adoption of the World Wide Web interface made the Internet more useful, more user-friendly, and consequently, more attractive to a generation raised using PCs.

The Web attracted a user base counted in the tens of millions, and many corporations began to carefully integrate Web compatibility into their planning. Lotus and IBM, the owners and developers of Notes—at one time the definitive model of groupware—were conspicuously absent from the first wave of Web-based collaborative software. Fully occupied as they were serving lucrative standalone networks for their clients and enterprise-level customers, they underestimated the degree to which the Web protocol would be adopted and the influence it would have on internal system design. The Web had lifted off without them, and its groupware vacuum had to be filled.

From its very beginning, the idea of groupware made perfect sense, but its adoption by organizations had been slowed by bad experiences, typically where design and implementation—the CSCW stage—had resulted in poor matches between social and workplace realities. Workers didn't use the tools, or if they did initially, they were likely to abandon them.

In retrospect, it's not surprising that organizations still in the early stages of companywide computer literacy found it difficult to be both laboratory guinea pigs and end-user customers of experimental software. The Web altered the game board of collaborative software design by providing designers with millions of eager guinea pigs and a gigantic test bed for online group interaction.

The Web's explosive growth moved the question of Internet integration into the corporate fast lane because new channels of contact had been opened with so many of the right kinds of customers. And because millions of those potential customers were interacting regularly with one another, interest in the adoption of groupware was promoted from an esoteric curiosity to a mainstream business consideration. Which is not to say that most companies then joined the groupware revolution, but they at least gained a passing familiarity with chat, message boards, and other manifestations of online group collaboration.

What is most important here is that the Web's user-friendly technology and its adoption by the masses drove its acceptance by business. The Web's simple utility generated a network effect, which the dictionary at Marketing Terms.com describes as "the phenomenon whereby a service becomes more valuable as more people use it, thereby encouraging ever-increasing numbers of adopters."[14] If someone's friend, business associate, or family was on the Web, that individual was more likely to get on the Web, too. This applied, likewise, to customers, partners, and competitors.

Surely, if so many were jumping at the chance to buy the equipment and learn the techniques required to connect to the Web, its methods deserved attention within the company. But even in companies where the executives remained ignorant of the Web's growing influence, workers, who surfed the Web from their home computers, launched guerilla marketing campaigns within their companies. Years of effort had gone into spreading the groupware gospel, but it took the Web, with its public demonstration of diverse and widespread group interaction, to seize the attention of most organizational decision makers.

The best of the Web-based collaboration tools were originally designed for use by masses of individual consumers, not by the staffs of organizations. Web ventures expected the industry's primary source of revenue to come from advertising dollars. People hooked on online conversation—clicking daily to new pages (and banner ads) with every new exchange of messages—offered the potential of a user-powered perpetual money machine. The Globe was one of the Web's early examples of online communities centered around an easy build-it-yourself homepage kit. It gained over 600 percent in share value on the day of its initial public offering (IPO) because investors assumed that its sticky social content and conversation would attract a captive, self-categorizing audience for high-value advertisers.

People, relationships, prefab home pages: The rush of users signing up to immerse themselves in the Web was described as doubling annually with no end in sight. But in the Web's stratospheric boom, overoptimistic marketers failed to see that such rabid infatuation with the Web's amusement park-like novelty would eventually wear off. Investors didn't realize that people would tire of clicking on banner ads or that, in the midst of interesting online social activity, they would simply ignore ads altogether. But that's exactly what happened, and the dreams of ad-supported interactivity died along with many other Web-based business models.

Today, The Globe is history, and the days of overblown expectations for commercial online communities have passed, but the tools developed to support group interaction on the Web are still widely used. Many chat room and message board interfaces are being overhauled and upgraded by their developers to serve a marketplace where organizations, rather than individual Web users, are beginning to express demand for powerful, flexible, collaboration-supporting online environments.

The idea of groupware has merged with the battle-tested, practical design of software meant to attract communities of special interest. But well-designed and robust technology is only part of the knowledge networking formula. How we behave as social creatures in electronic environments may be more important than the technology, as some experimental communities discovered in the pre-Web years.

A community is made up of people with common interests who communicate, form relationships, and establish shared history. The community is a basic social structure that we all recognize in our lives but often have a hard time describing. Try to name the specific communities you are a part of. Try to describe their boundaries and what defines them as communities. What does it take for someone to join your communities or to lose membership in them? Like us, you probably define them according to your feeling of membership. "If it feels like I'm part of a community, then it must be a community."

Communities have historically been defined by their geographical location because people needed to be in the same place to communicate. This is no longer the case. People can communicate very well using the Net, and since the first email messages were passed over the early ARPANET, communities have formed in its virtual space. Scientists working together on projects exchanged messages regularly over long periods of time, extending their limited opportunities to meet face to face through the use of electronic connections.

When the first publicly accessible electronic networks were launched in the late 1970s, the founders and first customers were people who once had access to the government-sponsored networks, usually as students or instructors on university campuses. They'd had a taste of the Net's utility and were willing to pay hefty hourly fees to use similar technologies through private networks. As the populations of these online gathering places grew, more people began to practice the art of informal knowledge networking. Changes in societal patterns, such as increased mobility and decreased involvement with local social activities, were also making the advantages of online communication more valuable as a means of staying in touch.

Howard Rheingold wrote The Virtual Community[15] in 1993 and exposed his readers not only to a new concept of social interaction but to the wide variety of people, ideas, and types of interaction that had been mixing for years through, around, and within the scattered experiments with computer-mediated communications. The stories in his book illustrate the overlap of friendship, intellectual stimulation, and professional interaction that characterized the early research and commercial networks. Rheingold states that people used CMC to "rediscover the power of cooperation," describing how their interaction represented "a merger of knowledge capital, social capital, and communion."

Murray Turoff built what Rheingold calls the "great-great-grandmother of all virtual communities" in 1976. Named Electronic Information Exchange System (EIES), it was funded by the National Science Foundation as "an electronic communication laboratory for use by geographically dispersed research communities." EIES served as a test bed for the use of online conferencing in problem-solving applications, and through people who spent time using the system, EIES got the word out among many students of organizational development about the useful potential of multiuser online conferencing.

On a separate track, Tom Truscott and James Ellis developed Usenet News in 1979 as a program to support ongoing stored-and-forwarded message-based interaction among users of computers that ran the UNIX operating system. Because it cost so much to connect to ARPANET, Usenet was created to be the "poor man's ARPANET." Usenet newsgroups began circulating among college campuses and other installations a year later, but distribution grew slowly.

The newsgroups were originally meant to be a discussion platform for questions and answers about UNIX and its technical administration. There were many UNIX enthusiasts and pioneers at AT&T Bell Labs, so the organization helped Usenet however it could. AT&T benefited from participating in Usenet newsgroups about improving the operation of internal email. Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) adopted Usenet and UNIX to help sell their UNIX-based computer systems. Usenet became the central knowledge base for discussion of the operating system that would eventually be the basis of the Internet and the model for all other multiuser, multitasking operating systems.

No one owned Usenet, and no one was in charge of the system that expanded faster and more widely than its creators had expected. It grew as much around a culture as it did around a technology. The original intention had been to provide a forum for mutual self-help among people facing similar technical problems, but the subject matter of newsgroups diversified quickly as Usenet got connected to ARPANET and, eventually, to the Internet. As Michael Hauben writes in a chapter of Netizens: An Anthology:

The number of sites receiving Usenet continually increased, demonstrating its popularity. People were attracted to Usenet because of what it made possible. People want to communicate and enjoy the thrill of finding others across the country (or today across the world) who share a common interest or just to be in touch with.[16]

Its popularity forced its loyal users to develop a code of rules for posting messages to newsgroups, with an entire category or domain of newsgroups devoted to orienting the newcomer to the virtual culture. The culture attempted to take care of the commons by instilling itself in its new members. It accomplished this through what Hauben calls the "contributed effort" of the people who donated content and the site administrators who maintained the systems required to run, maintain, and distribute news from their local Usenet installations.

Through its first decade, Usenet was available only to those who, through their school or workplace, had access to computers that could move newsgroups through modem connections or the ARPANET itself. But once habituated to Usenet, people who lost their access upon leaving a school or workplace were quite willing to pay for a connection to the growing collection of networked minds and ideas.

The first pay-for-access online discussion system was the Telecomputing Corporation of America, which Reader's Digest bought in 1980 and renamed "the Source." CompuServe was founded by H&R Block soon after. Joining either of these systems required an initial membership fee and hourly fees that varied with the time of day. An hour-a-day habit could easily cost hundreds of dollars per month, but thousands of people joined, even when the fastest modems ran at only .005 the speed of today's 56-kilobit-per-second (Kbps) modems.

Communities on these text-based systems formed around professional interests, hobbies, humor, current events, general technology, and most significantly, around the specific technologies of the systems that made the conversations possible. These self-tuning activities fascinated us at the WELL, and their practice is one of the great underappreciated assets of online discussion communities.

Using a collaborative interface, a group can learn through experience how to make its environment more conducive to achieving its needs and goals. Like Usenet, the subscription-based online communities showed that where members valued the online interaction they would, if allowed to, actively work to improve the system's design and operation.

People who describe themselves as "knowledge workers" are especially at home in the environment of the Net. The authors were privileged to be associated with one of the prime examples of grass-roots knowledge networking: the Whole Earth Lectronic Link, better known as the WELL.

The company was founded in 1985, and working as part of the WELL's small staff for 6 years convinced us that valued relationships could be developed and maintained purely through online communication. WELL members, like those of the Source and CompuServe, paid a significant amount to converse with a diverse selection of learned people on a wide variety of subjects.

There was always plenty of disagreement and some fairly spectacular feuds to spice up life in the virtual village, but most people logged in to find friendship and intellectual stimulation, not conflict. Many individuals separated by hundreds or thousands of miles became loyal friends and even professional partners exclusively through their online conversations and email. This took place at a time before people could build graphical home pages to describe themselves and their interests in minute detail. Instead, they made themselves known through their typed responses in online conversations.

WELL members occasionally referred to the bandwidth of relationship, meaning the amount of information that could be transmitted about each other's personal qualities through the medium of slow PCs and slow modems. Having only words on a screen to work with, and lacking pictures or sound to fill out one's description, we sought higher bandwidth through other means. One was the sparing use of symbols to convey emotions—the so-called smileys that employed punctuation marks to represent facial expressions. Another was the development of a local style of writing that included jargon and shorthand for adding personality and efficiency to messages. But the two most effective means for getting to know people were parties and a far-ranging selection of conversation topics.

Beginning in its second year, the WELL began holding monthly office parties open to members and their friends. These Friday night gabfests served as an excuse for in-person meetings with characters previously known only by their written words. Face-to-face (F2F) encounters raised the reality level of relationships, providing vivid mental referents for future online interactions.

Though many WELL members lived too far away from the San Francisco Bay Area to attend the parties, it was important for the WELL's overall community stability that as many people as possible got to know each other F2F. The WELLers who actually knew and trusted each other formed the core of the community, a social flywheel for interaction that could carry the soul of the community through difficult times.

The diversity of the WELL's structured online social environment was an equally important factor in establishing trust and familiarity between individual members. Well-rounded relationships could be based on the varied interaction that members shared around hobbies, family, personal life, entertainment, and world events.

The structure of the WELL's knowledge space was based on the conference: a collection of conversation topics with a common focus. Like a newspaper, the WELL had sections devoted to politics, sports, movies, and many of the area's local neighborhoods. It also had conferences for single people, married people, parents, writers, journalists, and computer geeks. It had a jokes conference, a future conference, and a sarcasm free-fire zone called Weird. The network of conferences permitted WELLers to build multidimensional familiarity with each other.

Joe might find Sue to be an obnoxious adversary in the politics conference but a compassionate advocate in the parenting conference. They might give each other helpful tips in the cooking conference and agree on the strengths of the latest mouse design in the Macintosh conference. But Sue might find Joe's jokes in Weird to be very strange and troubling. They might never meet in person, but they could at least know a lot about different aspects of each other's personality—enough to establish trust, if not to be the best of friends.

The WELL was founded on the groundbreaking publishing model of the Whole Earth Catalog, which intentionally blurred the boundary between publisher/ writer and consumer/reader. The catalogs had, for over a decade, invited readers to submit recommendations and reviews of products and articles about intriguing subjects. Such amateur authors were compensated modestly for their submissions, but many proved to be competent experts in their fields.

The WELL took this model online in a conversational format where members would submit the benefits of their experience and education to the curiosity of others. The voluntary sharing of knowledge fed on itself over the years, persuading members that if they gave freely of what they knew, they would get back at least equal value in kind.

The rewards from fellow WELL members might come in the form of useful facts, humor, moral support, advice, or opinion. They might come from someone for whom they'd provided help or from someone with whom they'd never interacted at all. Rather than just being a space for person-to-person knowledge barter, the WELL became a knowledge pool to which everyone gave and from which everyone could draw. It was both a knowledge marketplace and knowledge collective.

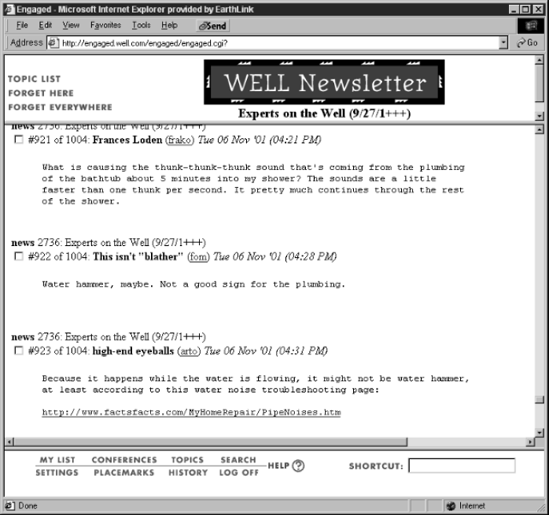

One of the community's earliest topics was called "Experts on the WELL." Today, more than 16 years after it was first started, the Experts topic is still active in its umpteenth incarnation. In Experts, a member posts a question and another member posts an answer. There's always a response and most of the time a definitive answer, though it often comes from a combination of people and pointers.

In Figure 2.1, a simple plumbing question elicits a straightforward suggestion and then a pointer to a source for what could be the comprehensive remedy. Experts is an informal and general resource. During the same period when this question about plumbing was posed, other questions addressed the molecular properties of different types of alcohol, a problem with Microsoft software that turned out to be a virus, the schedule of monarch butterfly migration to Big Sur, tenants rights laws in Marin County, and how to relight the pilot light in an oven. All were answered thoroughly and cooperatively. The catch on the WELL is that each question is likely to trigger an entire conversation, which by its volume makes the answers difficult to find later using the WELL's rudimentary data retrieval tools.

CourtesySalon.com

To reach such fluency in exchanging valuable and often hard-won knowledge, a large majority of WELL members had to trust each other. Most never got the chance to meet in person, and it took some time for interactions across a variety of conferences to build the level of familiarity that would allow members to "know" each other. Two years into its existence, Howard Rheingold and another community leader founded a conference named "True Confessions." Its purpose was to be a space for people to describe themselves through autobiographical stories. As it turned out, True accelerated the coalescence of WELL culture.

Chapter 6,In we'll include more about the effectiveness of stories in opening people up to each other and to new ways of thinking and generating knowledge. But suffice it to say that after people had posted true tales about their upbringing, about their adventures growing up, about their parents and siblings, or about how they found their life's work, membership in the WELL began to evoke feelings of living in a real-life village. When the Loma Prieta earthquake struck the Bay Area in 1989, the postquake support and caring reached an almost familial level.

It must be pointed out that the WELL's purpose was not to get work done. It was a small business that best described its mission as "selling its subscribers access to each other." It was in the relationship business more than the technical business, and to make the business work, the staff had to foster and maintain an overall atmosphere of trust. There was no common allegiance to a company to hold our members together, and many refused to trust certain other members even after True Confessions, the earthquake, several deaths in the family, and the passage of many years. But for the majority of people and the majority of relationships, the WELL's discussion space felt safe, open, and supportive.

Governance in the WELL's community was based on some simple guidelines. The first ground rule was "you own your own words," which meant that as a business the WELL would not be responsible for anything that any member posted on its site. Another founding principle was the distribution of power to responsible members who volunteered (or were appointed) to be conference hosts. Hosts presided over the hundreds of interest-based discussion locales of the WELL and qualified for their privileges through a combination of expertise in the subject, reliable presence and participation in their conference, and—we would always hope at the outset—responsible behavior as good representatives of WELL culture.

Hostship, with its power and responsibility, was awarded to almost as many people as volunteered to accept it. Hosts were empowered through the software to control and edit the content of their discussion areas, even to delete messages and entire conversations posted by their participants. Their powers to do harm through overcontrol were regulated by the cultural perception that censorship was a last-resort evil. Good hosts were assets to the business because they helped keep paying members interested and active, improving the quality of the WELL's content.

Hosts were rewarded for their help with free access to the system—a custom that was, for many years, the standard way that all online businesses managed their communities. This arrangement worked as long as online communities charged hourly membership fees, but when the business model changed to monthly flat fees in the mid-nineties, the rewards of free access became much more limited and AOL's volunteers challenged the legal fairness of being compensated with a mere $30 per month for many hours of valuable work. Good online discussion hosts deserve fair compensation, and within organizations good online hosts and facilitators are worth training and hiring for the difference they can make in knowledge-sharing discussion communities.

The WELL's one rule concerning bad behavior was conceived in response to actual experience. It outlawed intentional harassment and threatened any member who persisted in bothering another member with expulsion from the community by denying them further login privileges. As much as possible, WELL management encouraged self-governance and a sense of shared ownership and pride in the system, a strategy that seems to have worked more than it didn't.

The WELL is still active, with many of its early members still participating, even after 17 years. It has not grown steadily like AOL, which was founded around the same time, but the WELL was not built on the same business model, with the same motivations. It is a stable and persistent community, while there are very few such social entities living on AOL. The WELL's longevity has demonstrated the value of history in an online culture that, while not created to serve the knowledge needs of an organization, has enriched its members (and overall Net culture) in many ways.

One of the WELL's founders contributed its first central computer, six modems, a hard disk loaded with the UNIX operating system, and a software program called Picospan to support its online discussion. Picospan was a conferencing system, which put it in the category of asynchronous message boards. Members read the messages left on the system in its various boards or conferences and, when motivated to do so, wrote responding messages for others to read. Asychronicity means that WELL members didn't have to be online at the same time to converse. A response to a message might come in the next minute or the next month. A conversation might be displayed on the WELL for years. In fact, some historical conversations from 1986 can still be read today in the WELL's Archive conference.

Because members were permitted access to the operating system—the software layer that supported Picospan—the WELL was considered an open installation, where members with programming skills could build features and utilities for their own use or for the benefit of the community as a whole. Thus, the more the system was used, the more its users were able to improve upon its original features and operations.

One member wrote and donated the first user's manual. Another built the equivalent of today's instant messaging tools, allowing members who were logged in at the same time to communicate in real time, lending a greater sense of presence to their conversation. Another built a tool that allowed members to blank out or ignore the messages posted by other members who irritated them in some way. Called a bozo filter, its availability improved the perceived quality of online life while having a deterrent effect on behaviors intended to be abrasive. Thus, the environment of the WELL could be customized to fit the needs of its users, making it more useful, more appealing, and more consistent with the ways they managed relationships in the F2F world.

The WELL's example of user-driven software improvement is significant from a cost-management point of view. Any organization making decisions about software to support a knowledge network should consider that a flexible and easily customizable interface is better able to meet the evolving needs of the communities that use it. Buying a platform with rigid features—custom configured in advance of its actual use by "experts"—can freeze the community into processes that it finds neither natural nor comfortable. In Chapter 5, "Fostering a Knowledge-Sharing Culture," we'll describe some of the platforms that offer the design flexibility required by new conversational knowledge communities.

These early prototypes of knowledge-generating networks, pioneered by research communities and commercial providers, were like petri dishes, demonstrating the possibilities of using technical conversation interfaces for a variety of purposes and populations. Though some aimed to make large profits, many were satisfied with just breaking even or getting funded. All sought to stimulate activity and involvement.

The managers of these systems were focused on learning how to make their untried models work. They regarded their systems as full-time focus groups, testing the process of group problem solving in virtual environments. They listened for direction in refining their online interfaces to fit the specific needs of their communities. They involved themselves in conversations about governance and manners. They openly asked for advice and appreciated getting it. The relationship between management and customer was symbiotic, and this solid trust was needed going both ways.

The interaction on these systems resulted in many positive and surprising outcomes. One of the most fruitful by-products was the cross-pollination effect of different internal cultures brought together electronically. Groups whose physical paths might have never intersected were able to interface and integrate in a new knowledge nexus. In the most classic example, when technical people and nontechnical people communicated across the early networks, the alchemical combination provided a steady driving force for better product design.

The WELL was a tossed salad of professional writers, techno-geeks, counterculture veterans, journalists, Gen-Xers, futurists, scientists, musicians, artists, and fans of the Grateful Dead. These different communities met through the years under a variety of contexts: as cohorts, fellow parents, witnesses to disaster, seekers of discourse, observers of the world, business associates, concerned citizens, and attention seekers. Our conversations, at their best, were far ranging, witty, and passionate. At their worst, they were infuriating, depressing and passionate. All of this social and intellectual involvement made the community an always-open marketplace for hard-earned knowledge, hearsay, and opinion.

Pioneering systems like the WELL learned that certain hassles came with the human territory. Misunderstandings happened. Arguments and hurt feelings happened. So did feuds and fits, social sabotage, accusations, and the occasional rebellion or mutiny. People could be relied on to flip out from time to time as individuals or as groups. In many ways, both good and bad, social reality was plainly the same online as it was in the so-called real world. But some social games proved easier to play in virtual space than sitting across the table where one's nose might get punched.

Through using the tools of online group interaction, the community manager was able to learn in actual practice how to do a better job and produce a better product. But even that had to be learned. The immediate feedback that networked communities generated was a revelation to organizations that had not yet begun to use the technologies. The idea of the learning organization did not arise directly out of online discourse, but it was yet another response of the pressures of the Information Age.

Royal Dutch Shell, the global oil company, was among the first businesses to change emphasis from long-range planning to "the microcosm (the 'mental model') of our decision makers."[17] Peter Senge soon became the lead proponent of the idea of the learning organization, describing it as one "in which you cannot not learn because learning is so insinuated into the fabric of life." The people who comprise a learning organization are, he wrote, "continually enhancing their capacity to create what they want to create."

For the most part, the early online knowledge networks were informal exchanges among users with shared focus, compatible backgrounds, and enthusiasm for using the technology available to them. Their activities needed no official approval by the boss or company. People took part either on their own time or in pursuit of solutions for problems that they'd encountered in their workplace.

The idea of bringing such collaborative learning interaction into the organization was being tried only by a few companies. The concept of the learning organization was not originally framed around any technology at all. If the value of the company centered on learning, then whatever practice or technology could advance that value was likely to be pursued. Computer networks, as it turned out, fit many of the needs of the learning organization.

Few of the early virtual communities were assigned to do the organization's work. Some did generate knowledge that was used internally by the companies that sponsored them. But people didn't participate with the boss looking over their shoulders to see if they were affecting the bottom line. Informality was an advantage because their members felt free to say what they thought and to float new ideas even if they were off the wall. Informality took their collaboration out of the box.

One thing these experiments showed was that the most productive communities, from a business or organizational point of view, are those made up of people who communicate about what they do: their practice. Communities formed around common skills and knowledge are perhaps the most natural of associations and group identity beyond the family. One leading expert in applying the idea of communities of practice (CoPs) is Etienne Wenger, who got his Ph.D. in artificial intelligence and now works full time developing intelligence within groups of people with similar experience.

Wenger's definition of CoPs encompasses, "your local magician club, nurses in a ward, a street gang or a group of software engineers meeting regularly in the cafeteria to share tips."[18] Like workers in Japan and Korea, he equates knowing with doing. "Knowledge," he writes, "is an act of participation." Many of the earliest uses of computer networks were by communities of practice—the programmers who were building on the very networks they used as their primary meeting places. Now Wenger applies his principles to the situations of multinational corporations. We'll draw from his work in our discussion of the relationship between culture and technology in Chapter 7, "Choosing and Using Technology," and in some of our guides to knowledge network implementation in Chapter 8, "Initiating and Supporting Internal Conversation," and Chapter 9, "Conversing with External Stakeholders."

Not all virtual communities within the organization are CoPs, nor should they all be. Homogeneous communities of practice are valuable for their members, but cross-pollinated communities formed around diverse practices can create different types and hybrids of knowledge for the organization that can break new ground and discover novel solutions.

After the programmers, academics, and researchers pioneered the virtual meeting space, the next community of practice to blossom was that of customers— notably customers of some of the first personal computer products. This was a population of early adopters who found nothing more fascinating than the potential uses of these new tools and their operating languages. As soon as it became possible, they jumped on whatever manifestations of networked communication they could reach, from dialup BBSs to Usenet News. A new kind of relationship was being formed between companies and the people who used their products, and it wasn't the companies that initiated the relationship.

Apple computer was one of the earliest examples of a company whose customers used its products to communicate with each other and with the actual product designers and developers. According to the lore found on the Apple-fritter site,[19] Joe Torzewski started an Apple I users' group in 1977. Communication among fellow users and with Apple Computer initially took place through letters sent through the mail. Once the Apple II was released, the still-small company stopped supporting the Apple I and Joe, the customer, became Apple's main contact for supporting its first machine and its software.

The development of the Macintosh, in combination with the availability of modems and earlier Apple computers, spurred the growth of online user groups. The Stanford University Library's Macintosh history site[20] reports that user groups distributed software for the early Mac when commercial software companies were still in their formative stages. The groups circulated news and shared advice before Apple was ready to perform those duties. Enterprises for supporting the Mac grew out of the interaction and incubation of the user groups. The groups' newsletters also served as records of members' "dealings with the Macintosh," exposing bugs, tips, tricks, and shortcuts and reinforcing the cult status of the revolutionary new computer.

User groups also sprang up for other early computers and operating systems such as the Radio Shack TRS-80, the CP/M operating system, and the Atari. The users themselves began developing software products that could be used with these systems and made them available as "freeware" or at minimal prices as "shareware." Indeed, the customers were driving the knowledge marketplace around the PC revolution just as hard as the companies that were producing the hardware.

But it took a while, even after modems became commonplace, before the companies themselves joined the conversations directly. Of course, you were liable to encounter key developers of products (from Apple, at least) on the user group BBSs, but it wasn't until the common connectivity and common interface of the Web that the support function of the user communities had its counterpart within the company.

In late 1999, one of the authors of this book began a consulting engagement with Cisco Systems, helping them prepare to open a Web-based conversation with the networking professionals (NPs) who installed, configured, and maintained Cisco's equipment on customer sites. Cisco realized that there was plenty of room for improvement in its ability to support these thousands of technicians in the field, even though it already had one of the most advanced and sophisticated customer support operations anywhere. Cisco presented itself to the world as the leader of the migration to the Net. Its marketing slogan was, "Are you ready?" So it figured it needed to make itself readier by learning and applying the practice of virtual community.

The original vision inside the company was to provide a space where NPs could meet, share war stories, and suggest solutions for problems not covered in Cisco's extensive online documentation. Often, the problems encountered in the field were unknown to the customer service representatives who answered email and phone queries. The people using the equipment in unique situations were the sole owners of knowledge about how to resolve those situations. The NP community site would establish a space where those people could meet as a last resort and find the elusive answers to their questions under Cisco's URL.

The NP community was not meant to be a place to ask Cisco support questions. But Cisco's customer support staff, on hearing the idea, recognized it as a potential learning resource for them. They could learn from conversations between Cisco equipment users how to improve the company's documentation and support. The team working to develop the community interface and processes began to see how the conversations among expert users of the products could serve as a valuable pipeline into the minds of the customers for all of the company's product developers and marketers.

The community launched in the summer of 2000 and within a year had grown to such a level of activity that other divisions within Cisco asked to adapt the community software, management training, and design template for their own communities of practice and use. The evolution from a helpful service and a branding enhancement to an integral part of the service design process had taken root even as the company endured a brutal pounding in the marketplace.

Other technical companies such as Sun Microsystems, Hewlett-Packard, and Adobe had provided and supported online discussion communities with their customers for years. They still do so, not only as add-on services to their core products but also as a means of learning from some of the smartest and most relevant people they know: the customers who use and depend on their products.

These communications and information resources—reaching through the company firewall, extending from the internal networks that had been there for many years—were the first extranets made practical for many companies by the Web protocol. Here, too, technical companies took the lead, putting to use the very products they were developing.

For a company like Cisco, every useful application of networking justifies the purchase of their switches and routers. For Sun, every envelope-pushing idea for connecting the company with its customers is another clear example of why a network based on Sun servers and software would be worth buying. With technical products, the reasoning was clear. It was not so clear, though, to companies whose customers were behind the technical curve, without the connectivity or skills to participate online with their suppliers. The standardization of the Web interface has changed all that.

Extranets now connect organizations with the various communities defined by the buyer/seller relationship, information technology managers from companies seeking to make their systems compatible, and customers and their customer support teams. Extranets are used not only to coordinate data flow for transacting business, but they also provide meeting spaces for the kinds of knowledge that should be shared between the different links in the business chain. The implications of extranet-supported knowledge communities will be considered further in our chapters on culture (Chapter 6, "Taking Culture Online," and Chapter 7, "Choosing and Using Technology") and on external knowledge networking solutions (Chapter 9, "Conversing with External Stakeholders").

In 1995, the term portal was first used to describe a Web site. One didn't refer to them as Web companies because they had yet to prove themselves as viable businesses. But at about the same time, Yahoo, Excite, and Lycos began developing the idea of a single arrival page from which a user could find almost anything else on the Web. The site wasn't meant to be a final destination; it was designed to be a pass-through—a portal. For almost 3 years, these three leaders in the Web portal derby set the pace for stock valuation.

They had earned the status of Web companies for sure, but once the advertising model fell out of favor, their values deflated precipitously. But not before enterprises saw, in the portal model, an answer to their problems with trying to make complex information stashes more useful to their employees. The solution was a single starting point, with links to all the important people, forms, and information—a gathering place for the essentials that even a technophobe could deal with.

By the mid-nineties, intranets had connected the desktops within most large organizations, but in a slapdash manner. As new generations of software were introduced and new applications were added to the organization's internal systems, they were installed or upgraded and made available to the workers who needed them. But each new addition required new training for the workers and integration by IT. It seemed that the more powerful the company made its information systems, the more useless they became to the people who needed the information they contained. Email was available, but it was completely separate from the information systems. Online tools for continuous group interaction were rare or weakly supported, and few companies had the means for groups to view information together and discuss it through the intranet.

The Web protocol and the portal model offered new options to eliminate the chaos that intranet users had been experiencing. The challenge for IT, as the nineties came to a close, was to migrate intranet tools to the Web protocol. As we'll explore in Chapter 4, "The Role of IT in the Effective Knowledge Network," IT knew that life for them and for the organizations they supported would be easier if a common platform lay under all of the disparate internal applications and under the applications shared through the extranet as well. Once this conversion had taken place, the experience on the worker's desktop could be made more attractive and easier to use.

The modern intranet is now almost seamless with the Web. Of course, there are firewalls between it and the Web's wide open spaces, restricting who can get in and what can get out, but the user experience is consistent across the boundary. Hyperlinks open other pages or launch programs. Files can be exchanged and downloaded. Email can contain HTML. And conversation spaces can be imbedded within or proximate to the information that is relevant to them.

By bringing the Web into the organization, the possibilities for what can be accomplished through the intranet expand tremendously. Once this stage has been reached by IT, more than half the battle of knowledge networking has been won because the knowledge-as-object and knowledge-as-process approaches can be integrated. Content can be produced and moved around. Conversation can refer directly to content. Conversation can also be converted into content. Information can be put into context via discussion. People can be found by their skills and the knowledge they bring to the table. Communities of practice can meet and invite people with complementary skills to cross-pollinate their knowledge pools.

Maybe the most significant improvement is that power and responsibility can be easily distributed to the different realms of the intranet. Web-based interfaces allow department-level content production and interaction. New protocols like XML allow Web pages to exchange data with non-Web applications. And the flexibility of group conversation tools allows many configurations for meetings and support for working relationships within and between departments in the company. The intranet is no longer a bothersome system to use but has the potential of being a vital network for the entire organization.

The new intranet is presented as the primary foundation for building the knowledge network through the remainder of this book. But it's not the only format for generating and exchanging knowledge over today's Internet. Other software solutions and social configurations are becoming more important as organizations spread out geographically and simultaneously tighten the purse strings of their travel budgets.

Companies have more experience in producing face-to-face events than virtual ones. Gatherings called "knowledge fairs" have become one increasingly popular way of bringing the various departments, divisions, and teams of the company together in a physical space to catch up on who's doing what, which practices are working, and which discoveries are worth sharing in the mutual interest of the organization's success.

The time-and-place limitations of meeting face to face compared to meeting online are clear, as are the relationship bandwidth advantages of meeting in person. A consistent theme of this book is the trade-off of advantages between physical copresence and virtual communications. It's always important to combine and balance these two approaches in optimum proportion to fit organizational needs and budgets and to optimize knowledge-sharing relationships.

Events differ from ongoing conversations in that they are defined by beginnings and endings. Some events last only an hour; others go on for days or weeks. They take place through the Web, intranets, extranets, or special interfaces that run over the Internet. Some require high bandwidth connections, whereas others work over relatively slow modems. Events, like F2F conferences and meetings, have purpose and a focus. The handy thing about conducting these get-togethers online, aside from saving the time and cost of travel, is that they can be preserved, visited, and searched later through the wonders of digital storage technology.

Virtual knowledge networks make good use of the event format as a complement to the day-to-day exchanges that go on in message boards, email, and other more open-ended communications formats. Events provide opportunities for introducing new products, colleagues, and strategies. They attract attention and generate interest and enthusiasm around new knowledge networking communities. We'll describe the techniques for producing successful events in several formats in Chapter 8, "Initiating and Supporting Internal Conversation," and Chapter 9, "Conversing with External Stakeholders."

The current prospect of a slow economy combined with terror in the air has forced companies to reduce their travel budgets for attending meetings and conferences. Even staff located in different buildings on the corporate campus find it time-consuming to get together in person. More companies than ever are trying real-time video conferencing and groupware as the means for holding meetings.

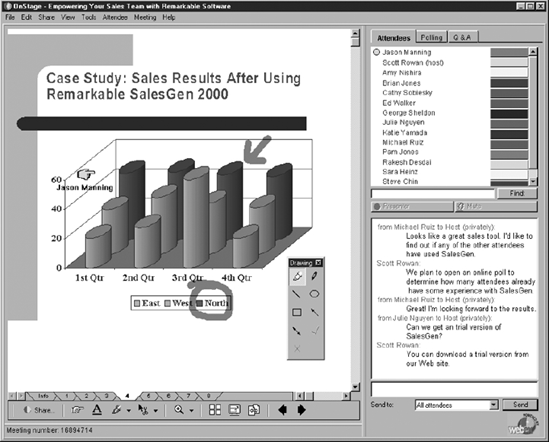

Companies, such as Webex and Placeware, "rent out" online meeting rooms to organizations by the event, by the week, or by the year (see Figure 2.2). They offer to provide online "facilitators" to manage the meetings, which can include slide presentations to the group and comments exchanged through text or simultaneous telephone conferencing.

Participants must be present to participate in such meetings, though they are usually recorded and can be played back when convenient for those who miss them or need to review them. Because some of these presentations include video feeds of the attendees, they provide the social bandwidth that many people appreciate (and some people dread.)

Like F2F meetings, these require coordinating schedules and, as companies become more international in scope, careful planning to include people across many time zones and local cultures. They answer the need for group communications that are direct and immediate in spite of the distance between participants. But in their limited timeframe, they do not encourage or support the kinds of thoughtful responses that can be composed in email or in asynchronous discussion boards, which are kinder to those with more problematic scheduling needs.

AOL has hosted online "celebrity events" since the early 1990s to build traffic and attract new members. Where else could one have a chance to ask Michael Jackson a question without leaving one's bedroom? Where else could 377,000 people simultaneously attend a live chat about the release of President Clinton's scandal-related tapes?

Courtesy of Webex, Inc.

As soon as the first commercial chat interfaces were designed for popular use on the Web, they were modified to include features—variously called auditoriums or forums—that allowed more than the usual number of chat attendees, while shielding designated special guests from direct contact by audience members. Questions and comments were sent through a moderator to be filtered and then relayed to the guest, who then responded directly back to the audience. Members of the audience could chat with others in their same virtual row but not with people in other rows. The celebrity event worked very well as a marketing technique, so naturally, companies that were not networking entertainment giants like AOL also began to try it in different formats but with the same intentions of attracting an audience.

The ability to hold virtual meetings—where audiences could be addressed by and interact with special guests—fit into the marketing needs of wired corporations once enough of their customers, partners, and investors were found to have access to the Internet. This became even more important and valuable when SEC regulations began to require public companies to share information equitably for all of their investors. The corporate "conference call" could now include audiences numbered in the thousands.

Product rollouts, demonstrations, training sessions, and press conferences can all take place now completely online, attracting people who never would have gone out of their way to attend a live promotion event in a hotel ballroom in their hometown, much less in another city on the other side of the continent. The knowledge networking aspects lay in the ability to reach a wider audience with current information and to gather feedback immediately or within a limited timespan.

The quality of response when the audience is able to carry on a give-and-take dialogue with an authority is much higher than what can be gleaned from polls and surveys. But showcase events tend to be asymmetric in the amount of information going out to the audience compared to the amount coming in. For real learning over a limited timespan, more conversational formats can provide better results.

The online conference is another type of knowledge-sharing event. It employs asynchronous tools—which, for clarity sake, we refer to generically as message boards—and lasts longer than the real-time meetings just described: from a full day to a month or more. These formats are used widely in the e-learning sphere, where students tend to have full-time jobs and can only participate when their busy schedules allow. Interaction takes place over time, and students are often required to post messages and responses as evidence of their engagement in the learning process. Where the context is not formal education but organizational learning and knowledge exchange, the format is similar, but one's participation is "graded" in other ways.

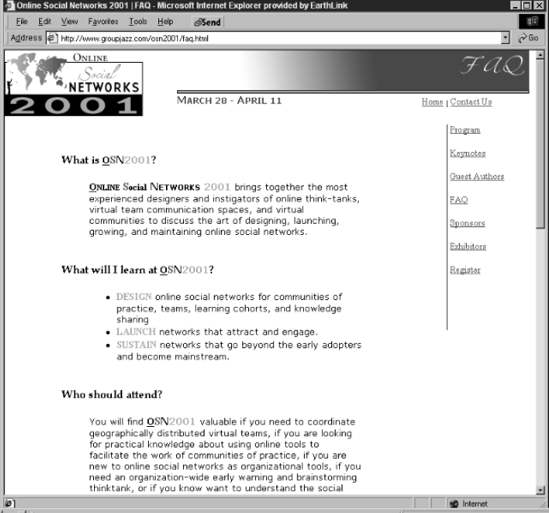

Lisa Kimball is a veteran in producing group events. Her company, Group Jazz, combines the use of online tools and F2F interaction with the practical skills of facilitation and virtual teamwork. Group Jazz produced Mathweb 2000, a professional conference with sponsors such as PBS and the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. It also produced Online Social Networking 2001 (see Figure 2.3), which Kimball describes as "an online conference to help companies understand why and how to organize, lead, manage, value, and sustain internal online social networks for teams, communities of practice, learning cohorts, and other mission-oriented groups."

Such formats—where experts attend online and "speak" on their specialties and where the ensuing discussions blur the lines between experts and people seeking to learn new skills—are applicable to communities of practice, internal training programs, and marketing-focused conferences. We'll elaborate on the techniques for producing virtual seminars in Chapter 8, "Initiating and Supporting Internal Conversation," and Chapter 9, "Conversing with External Stakeholders."

In May 2001, IBM held an online brainstorming extravaganza that it called WorldJam. Over the 3 days of the event, 52,000 of its 320,000 employees logged in and contributed over 6,000 ideas and opinions about the operations, processes, products, and organization of their employer. The end result of this invitation for workplace input was an archive of comments that continued to be visited heavily by employees in the days immediately after the event. It was, at least, an occasion for global IBM visibility, but the internal analysis of the shared knowledge and its application went on for months, reportedly yielding enough useful information to justify its costs.

Courtesy of Group Jazz

Though it was certainly a large event in terms of intentional participation, its perception as a success was tempered (for us at least) by the seemingly low worker response, which in itself could be a valuable indicator of employee sentiment. IBM's figures report that, given the advance invitation and opportunity over 3 days, only one of six IBM employees bothered to log on. Those relative few contributed only 6,000 proposals and comments.

Does this mean that IBM is an organization whose workers feel no incentive to take advantage of a risk-free opportunity to sound off or communicate with fellow employees about improving the company? Or does it simply demonstrate that over 80 percent of the employees think everything is as fine as it can be? It's hard to say, but it's clear that a culture for using online communications has not yet permeated IBM.

For comparison, we can look at a system that one of the authors managed for over a year. The estimated 20,000 active members of the Table Talk online discussion community on Salon.com posted over 6,000 new messages almost every weekday in 1999. These people had little, if any, stake in the success of Salon.com as compared to the workers who most definitely had a stake in suggesting improvements to IBM. Yet, WorldJam stood out at the time as the most visible and spectacular demonstration to that date of the use of the Net as a channel for gathering internal input to a large organization. Maybe many of IBM's employees felt it safer to refrain from posting their 2-cents worth, whereas Table Talk's members stood no risk of being fired or demoted no matter what they posted.

The greatest immeasurable benefit to IBM of WorldJam may have been a boost in employee perception of the company. As distinguished from the usual secrecy (or disdain) with which feedback from the workplace is treated by management, the open nature of WorldJam's forum may have demonstrated something significant to IBM's employees: that the company was willing to let the world know that it welcomed widespread input and that it trusted the medium of the Net as the channel for that input. Whether the company keeps the communications channels open for continuing conversation and whether the employees make greater use of those channels will determine, in our eyes, the real and lasting impact and success of the event.

Much key knowledge is also held outside the organization in the minds and opinions of customers and constituents. It's still a sad fact that most Web sites provide a contact us link to which no real person is assigned responsibility to respond as the us. But customers on the Web—now accustomed to the immediacy of online communication through email, chat, instant messaging, and online discussion—are more eager than corporations are aware to offer their feedback and suggestions as long as they believe it will have some effect on the company to which it's directed. Some businesses have begun to seek this input directly from customers on the Web, with or without the customers' prior knowledge.

IBM let the world know of its active listening through dedicated chat rooms, message boards, and surveys. Other companies do their listening more surrep-titiously—not in dedicated message systems and communities but in public discussion spaces across the Web, where people who are likely to fit their target demographics tend to log on regularly and converse. Some companies train and assign internal employees to this task, and others provide the service under contract and send in regular reports of customer feedback and commentary to their clients.

A USA Today story[21] told of a man, calling himself "the Starwood Lurker," who would troll the Internet, dipping into frequent-traveler electronic bulletin boards to check the postings about his employer, Starwood Hotels & Resorts. The lurker scanned for comments about big hotel chains operating under Star-wood's corporate umbrella, which included Westin, Sheraton, St. Regis, and W, and when he found such comments, he'd respond to them, usually through email. The reaction from frequent travelers (according to the company) was almost always positive as travelers appreciated the concern and the customer service outreach.

Most companies consider this kind of activity—whether they have an employee do it or hire a specialty service to scan the Web for comments about them—to be more in the realm of customer relationship management (CRM) than knowledge gathering. But this is where the lines blur between the two intentions. Learning about customer attitudes builds knowledge that can lead to happier customers and better customer relationships. But the company doesn't have to go lurking around the Web or send a Web clipping service out on its behalf. It can instead create a dedicated space for customers to gather and interact, not as a focus group, but more like a customers' think tank.

Hallmark greeting cards decided that it needed to know more about how its typical customers lived to understand the kinds of products they needed and were willing to buy. Instead of asking customers directly about their preferences, they invited a group of their female customers to join "Idea Exchange," an online discussion community where they would be encouraged to get to know each other and interact informally over time.

There was no schedule or set of topics to follow—just a group of women talking online about their lives, their concerns, their joys, and their challenges. Hallmark unobtrusively, and with the participants' full knowledge, listened in and learned. As Business Week reported: "Many say they love tuning into their own soap opera every day. They sign on when they have a moment, chat among themselves, post pictures of home decorations at Hallmark's prompting, and answer the company's questions about products and ideas."[22]

From the interaction, Hallmark discovered new opportunities for products that stood a good chance of selling because they met consensus needs of these 200 women. It was relatively cheap to pull off, and it achieved a depth of meaning that gave the input far more impact than that of a focus group or survey.

Competitive pressures to provide better customer service and develop improved customer products are forcing companies to use the Web as a research tool for learning more about how their customers think, behave, and make their buying decisions. It's the kind of knowledge that can translate directly into business success.

The Information Age brought new technologies and new needs to organizations. The technologies gave birth to new methods for bringing groups together around common interests. People communicating through electronic networks were able to collaborate on improving these networks and thus work more effectively as communities in the new meeting space of the Net. Early pioneering systems established precedents and spread practical ideas for dealing with social realities in environments where people were not physically together. Now these ideas and practices are being integrated into the wired organization.

The vanguard in putting networks to social use was made up of early adopters who were most ready to deal with the new technology. Similarly, the leading groups in populating organizational networks are likely to be people most familiar with communicating online and most motivated to go through the adjustment and improvement period that comes with every new online application. Groups that work together for mutual benefit, like the user groups in the early days of personal computers, will push knowledge networks ahead.

There are now many options for creating and designing online group interaction, and they all have different strengths. The organization today can talk to itself through its workers; it can talk with its customers and with collaborating partner organizations all through the uniformity of the Web protocol. There are software solutions for use in intranets and extranets to share information and knowledge in many formats, and the pioneers of the past years have been making use of the ubiquitous Web interface to learn more about their customers and workers.

There are many solutions and promising new techniques, but there are still many questions to be answered and predictable problems to be dealt with in every attempt to form conversational communities for generating knowledge. The next chapter describes these challenges and the solutions and attitudes that can be applied to counter them.