The Risk Management Process

By now you should believe that risk management is critical to the long-term security (and even success) of your organization. But how do you get this done? NIST SP 800-39 describes four interrelated components that comprise the risk management process. Let’s consider each of these components briefly now, since they will nicely frame the remainder of our discussion of risk management.

• Frame risk Risk framing defines the context within which all other risk activities take place. What are our assumptions and constraints? What are the organizational priorities? What is the risk tolerance of senior management?

• Assess risk Before we can take any action to mitigate risk, we have to assess it. This is perhaps the most critical aspect of the process, and one that we will discuss at length. If your risk assessment is spot-on, then the rest of the process becomes pretty straightforward.

• Respond to risk By now, we’ve done our homework. We know what we should, must, and can’t do (from the framing component), and we know what we’re up against in terms of threats, vulnerabilities, and attacks (from the assess component). Responding to the risk becomes a matter of matching our limited resources with our prioritized set of controls. Not only are we mitigating significant risk, but, more importantly, we can tell our bosses what risk we can’t do anything about because we’re out of resources.

• Monitor risk No matter how diligent we’ve been so far, we probably missed something. If not, then the environment likely changed (perhaps a new threat source emerged or a new system brought new vulnerabilities). In order to stay one step ahead of the bad guys, we need to continuously monitor the effectiveness of our controls against the risks for which we designed them.

You will notice that our discussion of risk so far has dealt heavily with the whole framing process. In the preceding sections, we’ve talked about the organization (top to bottom), the policies, and the team. The next step is to assess the risk, and what better way to start than by modeling the threat.

Threat Modeling

Before we can develop effective defenses, it is imperative to understand the assets that we value, as well as the threats against which we are protecting them. Though multiple definitions exist for the term, for the purposes of our discussion we define threat modeling as the process of describing feasible adverse effects on our assets caused by threat sources. That’s quite a mouthful, so let’s break it down. When we build a model of the threats we face, we want to ground them in reality, so it is important to only consider dangers that are reasonably likely to occur. To do otherwise would dilute our limited resources to the point of making us unable to properly defend ourselves.

You could argue (correctly) that threat modeling is a component task to the risk assessment that we will discuss in the next section. However, many organizations are stepping up threat intelligence efforts at an accelerated pace. Threat intelligence is becoming a resource that is used not only by the risk teams, but also by the security operations, development, and even management teams. We isolate threat modeling from the larger discussion of risk assessment here to highlight the fact that it serves more than just risk assessment efforts and allows an organization to understand what is in the realm of the probable and not just the possible.

Threat Modeling Concepts

To focus our efforts on the likely (and push aside the less likely), we need to consider what it is that we have that someone (or something) else may be able to degrade, disrupt, or destroy. As we will see shortly, inventorying and categorizing our information systems is a critical early step in the process. For the purpose of modeling the threat, we are particularly interested in the vulnerabilities inherent in our systems that could lead to the compromise of their confidentiality, integrity, or availability. We then ask the question, “Who would want to exploit this vulnerability, and why?” This leads us to a deliberate study of our potential adversaries, their motivations, and their capabilities. Finally, we determine whether a given threat source has the means to exploit one or more vulnerabilities in order to attack our assets.

Vulnerabilities

Everything built by humans is vulnerable to something. Our information systems, in particular, are riddled with vulnerabilities even in the best-defended cases. One need only read news accounts of the compromise of the highly protected and classified systems of defense contractors and even governments to see that this universal principle is true. In order to properly analyze vulnerabilities, it is useful to recall that information systems consist of information, processes, and people that are typically, but not always, interacting with computer systems. Since we discuss computer system vulnerabilities in detail in Chapter 3 (which covers domain 3, Security Architecture and Engineering), we will briefly discuss the other three components here.

Information In almost every case, the information at the core of our information systems is the most valuable asset to a potential adversary. Information within a computer information system (CIS) is represented as data. This information may be stored (data at rest), transported between parts of our system (data in motion), or actively being used by the system (data in use). In each of its three states, the information exhibits different vulnerabilities, as listed in the following examples:

• Data at rest Data is copied to a thumb drive and given to unauthorized parties by an insider, thus compromising its confidentiality.

• Data in motion Data is modified by an external actor intercepting it on the network and then relaying the altered version (known as a man-in-the-middle or MitM attack), thus compromising its integrity.

• Data in use Data is deleted by a malicious process exploiting a “time of check to time of use” (TOC/TOU) or “race condition” vulnerability, thus compromising its availability. We address this in detail in Chapter 3 (which covers domain 3, Security Architecture and Engineering).

Processes Processes are almost always instantiated in software as part of a CIS. Therefore, process vulnerabilities can be thought of as a specific kind of software vulnerability. We will address these in detail in Chapter 8 (which covers domain 8, Software Development Security). As security professionals, however, it is important that we take a broader view of the issue and think about the business processes that are implemented in our software systems.

People There are many who would consider the human the weakest link in the security chain. Whether or not you agree with this, it is important to consider the specific vulnerabilities that people present in a system. Though there are many ways to exploit the human in the loop, there are three that correspond to the bulk of the attacks, summarized briefly here:

• Social engineering This is the process of getting a person to violate a security procedure or policy, and usually involves human interaction or e-mail/text messages.

• Social networks The prevalence of social network use provides potential attackers with a wealth of information that can be leveraged directly (e.g., blackmail) or indirectly (e.g., crafting an e-mail with a link that is likely to be clicked) to exploit people.

• Passwords Weak passwords can be cracked in milliseconds using rainbow tables (discussed in Chapter 5) and are very susceptible to dictionary or brute-force attacks. Even strong passwords are vulnerable if they are reused across sites and systems.

Threats

As you identify the vulnerabilities that are inherent to your organization and its systems, it is important to also identify the sources that could attack them. The International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission in their ISO/IEC standard 27000 define a threat as a “potential cause of an unwanted incident, which may result in harm to a system or organization.” While this may sound somewhat vague, it is important to include the full breadth of possibilities.

Perhaps the most obvious threat source is the malicious attacker who intentionally pokes and prods our systems looking for vulnerabilities to exploit. In the past, this was a sufficient description of this kind of threat source. Increasingly, however, organizations are interested in profiling the threat in great detail. Many organizations are implementing teams to conduct cyberthreat intelligence that allows them to individually label, track, and understand specific cybercrime groups. This capability enables these organizations to more accurately determine which attacks are likely to originate from each group based on their capabilities as well as their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP).

Another important threat source is the insider, who may be malicious or simply careless. The malicious insider is motivated by a number of factors, but most frequently by disgruntlement and/or financial gain. In the wake of the massive leak of classified data attributed to Edward Snowden in 2012, there’s been increased emphasis on techniques and procedures for identifying and mitigating the insider threat source. While the deliberate insider dominates the news, it is important to note that the accidental insider can be just as dangerous, particularly if they fall into one of the vulnerability classes described in the preceding section.

Finally, the nonhuman threat source can be just as important as the ones we’ve previously discussed. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011 serve as reminders that natural events can be more destructive than any human attack. They also force the information systems security professional to consider threats that fall way outside the norm. Though it is easier and in many cases cheaper to address likelier natural events such as a water main break or a fire in a facility, one should always look for opportunities to leverage countermeasures that protect against both mild and extreme events for small price differentials.

Threat Modeling Methodologies

If the vulnerability is on one end of a network and the threat source is on the other, it is the attack that ties them together. In other words, if a given threat (e.g., a disgruntled employee) wants to exploit a given vulnerability (e.g., the e-mail inbox of the company’s president), but lacks the means to do so, then an attack would likely not be feasible and this scenario would not be part of our threat model. It is not possible to determine the feasibility of an attack if we don’t know who would execute it and against which vulnerability. This shows how it is the triads formed by an existent vulnerability, a feasible attack, and a capable threat that constitute the heart of a threat model. Because there will be an awful lot of these possible triads in a typical organization, we need systematic approaches to identifying and analyzing them. This is what threat modeling methodologies give us.

Attack Trees

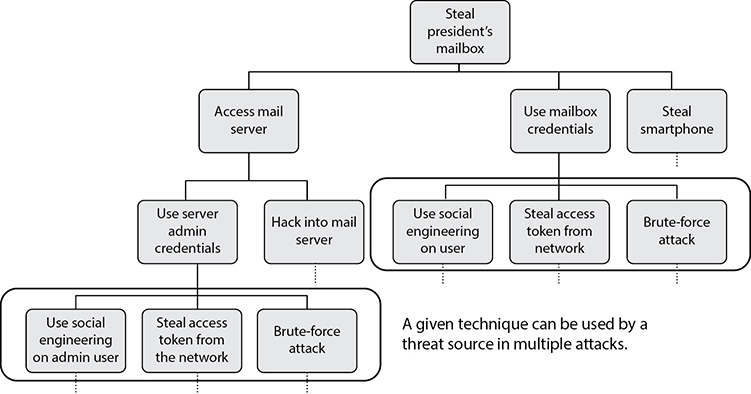

This methodology is based on the observation that, typically, there are multiple ways to accomplish a given objective. For example, if a disgruntled employee wanted to steal the contents of the president’s mailbox, this could be accomplished by either accessing the e-mail server, obtaining the password, or stealing the president’s laptop. Accessing the e-mail server could be accomplished by using administrative credentials or by hacking in. To get the credentials, one could use brute force or social engineering. The branches created by each decision point create what is known as an attack tree, an example of which for this scenario is shown in Figure 1-13. Each of the leaf nodes represents a specific condition that must be met in order for the parent node to be effective. For instance, to effectively obtain the mailbox credentials, the employee could have stolen a network access token. Given that the employee has met the condition of having the credentials, he would then be able to steal the contents of the president’s mailbox. A successful attack, then, is one in which the attacker traverses from a leaf node all the way to the root of the tree.

Figure 1-13 A simplified attack tree

NOTE The terms “attack chain” and “kill chain” are commonly used. They refer to a specific type of attack tree that has no branches and simply proceeds from one stage or action to the next. The attack tree is much more expressive in that it shows many ways in which an attacker can accomplish each objective.

Reduction Analysis

The generation of attack trees for an organization usually requires a large investment of resources. Each vulnerability-threat-attack triad can be described in detail using an attack tree, so you end up with as many trees as you do triads. To defeat each of the attacks you identify, you would typically need a control or countermeasure at each leaf node. Since one attack generates many leaf nodes, this has a multiplicative effect that could make it very difficult to justify the whole exercise. However, attack trees lend themselves to a methodology known as reduction analysis.

There are two aspects of reduction analysis in the context of threat modeling: one aspect is to reduce the number of attacks we have to consider, and the other is to reduce the threat posed by the attacks. The first aspect is evidenced by the commonalities in the example shown in Figure 1-13. To satisfy the conditions for logging into the mail server or the user’s mailbox, an attacker can use the exact same three techniques. This means we can reduce the number of conditions we need to mitigate by finding these commonalities. When you consider that these three sample conditions apply to a variety of other attacks, you realize that we can very quickly cull the number of conditions to a manageable number.

The second aspect of reduction analysis is the identification of ways to mitigate or negate the attacks we’ve identified. This is where the use of attack trees can really benefit us. Recall that each tree has only one root but many leaves and internal nodes. The closer you are to the root when you implement a mitigation technique, the more leaf conditions you will defeat with that one control. This allows you to easily identify the most effective techniques to protect your entire organization. These techniques are typically called controls or countermeasures.

Risk Assessment and Analysis

A risk assessment, which is really a tool for risk management, is a method of identifying vulnerabilities and threats and assessing the possible impacts to determine where to implement security controls. After parts of a risk assessment are carried out, the results are analyzed. Risk analysis is a detailed examination of the components of risk used to ensure that security is cost effective, relevant, timely, and responsive to threats. It is easy to apply too much security, not enough security, or the wrong security controls and to spend too much money in the process without attaining the necessary objectives. Risk analysis helps companies prioritize their risks and shows management the amount of resources that should be applied to protecting against those risks in a sensible manner.

NOTE The terms risk assessment and risk analysis, depending on who you ask, can mean the same thing, or one must follow the other, or one is a subpart of the other. Here, we treat risk assessment as the broader effort, which is reinforced by specific risk analysis tasks as needed. This is how you should think of it for the CISSP exam.

Risk analysis has four main goals:

• Identify assets and their value to the organization.

• Determine the likelihood that a threat exploits a vulnerability.

• Determine the business impact of these potential threats.

• Provide an economic balance between the impact of the threat and the cost of the countermeasure.

Risk analysis provides a cost/benefit comparison, which compares the annualized cost of controls to the potential cost of loss. A control, in most cases, should not be implemented unless the annualized cost of loss exceeds the annualized cost of the control itself. This means that if a facility is worth $100,000, it does not make sense to spend $150,000 trying to protect it.

It is important to figure out what you are supposed to be doing before you dig right in and start working. Anyone who has worked on a project without a properly defined scope can attest to the truth of this statement. Before an assessment is started, the team must carry out project sizing to understand what assets and threats should be evaluated. Most assessments are focused on physical security, technology security, or personnel security. Trying to assess all of them at the same time can be quite an undertaking.

One of the risk assessment team’s tasks is to create a report that details the asset valuations. Senior management should review and accept the list and make them the scope of the risk management project. If management determines at this early stage that some assets are not important, the risk assessment team should not spend additional time or resources evaluating those assets. During discussions with management, everyone involved must have a firm understanding of the value of the security AIC triad—availability, integrity, and confidentiality—and how it directly relates to business needs.

Management should outline the scope of the assessment, which most likely will be dictated by organizational compliance requirements as well as budgetary constraints. Many projects have run out of funds, and consequently stopped, because proper project sizing was not conducted at the onset of the project. Don’t let this happen to you.

A risk assessment helps integrate the security program objectives with the company’s business objectives and requirements. The more the business and security objectives are in alignment, the more successful the two will be. The assessment also helps the company draft a proper budget for a security program and its constituent security components. Once a company knows how much its assets are worth and the possible threats they are exposed to, it can make intelligent decisions about how much money to spend protecting those assets.

A risk assessment must be supported and directed by senior management if it is to be successful. Management must define the purpose and scope of the effort, appoint a team to carry out the assessment, and allocate the necessary time and funds to conduct it. It is essential for senior management to review the outcome of the risk assessment and to act on its findings. After all, what good is it to go through all the trouble of a risk assessment and not react to its findings? Unfortunately, this does happen all too often.

Risk Assessment Team

Each organization has different departments, and each department has its own functionality, resources, tasks, and quirks. For the most effective risk assessment, an organization must build a risk assessment team that includes individuals from many or all departments to ensure that all of the threats are identified and addressed. The team members may be part of management, application programmers, IT staff, systems integrators, and operational managers—indeed, any key personnel from key areas of the organization. This mix is necessary because if the team comprises only individuals from the IT department, it may not understand, for example, the types of threats the accounting department faces with data integrity issues, or how the company as a whole would be affected if the accounting department’s data files were wiped out by an accidental or intentional act. Or, as another example, the IT staff may not understand all the risks the employees in the warehouse would face if a natural disaster were to hit, or what it would mean to their productivity and how it would affect the organization overall. If the risk assessment team is unable to include members from various departments, it should, at the very least, make sure to interview people in each department so it fully understands and can quantify all threats.

The risk assessment team must also include people who understand the processes that are part of their individual departments, meaning individuals who are at the right levels of each department. This is a difficult task, since managers tend to delegate any sort of risk assessment task to lower levels within the department. However, the people who work at these lower levels may not have adequate knowledge and understanding of the processes that the risk assessment team may need to deal with.

The Value of Information and Assets

The value placed on information is relative to the parties involved, what work was required to develop it, how much it costs to maintain, what damage would result if it were lost or destroyed, what enemies would pay for it, and what liability penalties could be endured. If a company does not know the value of the information and the other assets it is trying to protect, it does not know how much money and time it should spend on protecting them. If the calculated value of your company’s secret formula is x, then the total cost of protecting it should be some value less than x. The value of the information supports security measure decisions.

The previous examples refer to assessing the value of information and protecting it, but this logic applies toward an organization’s facilities, systems, and resources. The value of the company’s facilities must be assessed, along with all printers, workstations, servers, peripheral devices, supplies, and employees. You do not know how much is in danger of being lost if you don’t know what you have and what it is worth in the first place.

Costs That Make Up the Value

An asset can have both quantitative and qualitative measurements assigned to it, but these measurements need to be derived. The actual value of an asset is determined by the importance it has to the organization as a whole. The value of an asset should reflect all identifiable costs that would arise if the asset were actually impaired. If a server cost $4,000 to purchase, this value should not be input as the value of the asset in a risk assessment. Rather, the cost of replacing or repairing it, the loss of productivity, and the value of any data that may be corrupted or lost must be accounted for to properly capture the amount the organization would lose if the server were to fail for one reason or another.

The following issues should be considered when assigning values to assets:

• Cost to acquire or develop the asset

• Cost to maintain and protect the asset

• Value of the asset to owners and users

• Value of the asset to adversaries

• Price others are willing to pay for the asset

• Cost to replace the asset if lost

• Operational and production activities affected if the asset is unavailable

• Liability issues if the asset is compromised

• Usefulness and role of the asset in the organization

Understanding the value of an asset is the first step to understanding what security mechanisms should be put in place and what funds should go toward protecting it. A very important question is how much it could cost the company to not protect the asset.

Determining the value of assets may be useful to a company for a variety of reasons, including the following:

• To perform effective cost/benefit analyses

• To select specific countermeasures and safeguards

• To determine the level of insurance coverage to purchase

• To understand what exactly is at risk

• To comply with legal and regulatory requirements

Assets may be tangible (computers, facilities, supplies) or intangible (reputation, data, intellectual property). It is usually harder to quantify the values of intangible assets, which may change over time. How do you put a monetary value on a company’s reputation? This is not always an easy question to answer, but it is important to be able to do so.

Identifying Vulnerabilities and Threats

Earlier, it was stated that the definition of a risk is the probability of a threat agent exploiting a vulnerability to cause harm to an asset and the resulting business impact. Many types of threat agents can take advantage of several types of vulnerabilities, resulting in a variety of specific threats, as outlined in Table 1-5, which represents only a sampling of the risks many organizations should address in their risk management programs.

Table 1-5 Relationship of Threats and Vulnerabilities

Other types of threats can arise in an environment that are much harder to identify than those listed in Table 1-5. These other threats have to do with application and user errors. If an application uses several complex equations to produce results, the threat can be difficult to discover and isolate if these equations are incorrect or if the application is using inputted data incorrectly. This can result in illogical processing and cascading errors as invalid results are passed on to another process. These types of problems can lie within applications’ code and are very hard to identify.

User errors, whether intentional or accidental, are easier to identify by monitoring and auditing user activities. Audits and reviews must be conducted to discover if employees are inputting values incorrectly into programs, misusing technology, or modifying data in an inappropriate manner.

Once the vulnerabilities and associated threats are identified, the ramifications of these vulnerabilities being exploited must be investigated. Risks have loss potential, meaning what the company would lose if a threat agent actually exploited a vulnerability. The loss may be corrupted data, destruction of systems and/or the facility, unauthorized disclosure of confidential information, a reduction in employee productivity, and so on. When performing a risk assessment, the team also must look at delayed loss when assessing the damages that can occur. Delayed loss is secondary in nature and takes place well after a vulnerability is exploited. Delayed loss may include damage to the company’s reputation, loss of market share, accrued late penalties, civil suits, the delayed collection of funds from customers, resources required to reimage other compromised systems, and so forth.

For example, if a company’s web servers are attacked and taken offline, the immediate damage (loss potential) could be data corruption, the man-hours necessary to place the servers back online, and the replacement of any code or components required. The company could lose revenue if it usually accepts orders and payments via its website. If it takes a full day to get the web servers fixed and back online, the company could lose a lot more sales and profits. If it takes a full week to get the web servers fixed and back online, the company could lose enough sales and profits to not be able to pay other bills and expenses. This would be a delayed loss. If the company’s customers lose confidence in it because of this activity, it could lose business for months or years. This is a more extreme case of delayed loss.

These types of issues make the process of properly quantifying losses that specific threats could cause more complex, but they must be taken into consideration to ensure reality is represented in this type of analysis.

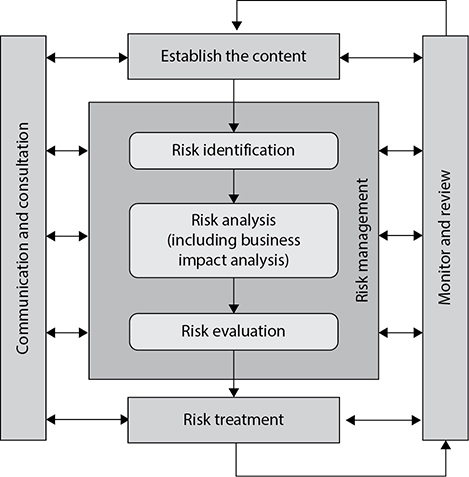

Methodologies for Risk Assessment

The industry has different standardized methodologies when it comes to carrying out risk assessments. Each of the individual methodologies has the same basic core components (identify vulnerabilities, associate threats, calculate risk values), but each has a specific focus. As a security professional it is your responsibility to know which is the best approach for your organization and its needs.

NIST developed a guide for conducting risk assessments, which is published in SP 800-30, Revision 1. It is specific to information systems threats and how they relate to information security risks. It lays out the following steps:

1. Prepare for the assessment.

2. Conduct the assessment:

a. Identify threat sources and events.

b. Identify vulnerabilities and predisposing conditions.

c. Determine likelihood of occurrence.

d. Determine magnitude of impact.

e. Determine risk.

3. Communicate results.

4. Maintain assessment.

The NIST risk management methodology is mainly focused on computer systems and IT security issues. It does not explicitly cover larger organizational threat types, as in succession planning, environmental issues, or how security risks associate to business risks. It is a methodology that focuses on the operational components of an enterprise, not necessarily the higher strategic level.

A second type of risk assessment methodology is called FRAP, which stands for Facilitated Risk Analysis Process. The crux of this qualitative methodology is to focus only on the systems that really need assessing, to reduce costs and time obligations. It stresses prescreening activities so that the risk assessment steps are only carried out on the item(s) that needs it the most. FRAP is intended to be used to analyze one system, application, or business process at a time. Data is gathered and threats to business operations are prioritized based upon their criticality. The risk assessment team documents the controls that need to be put into place to reduce the identified risks along with action plans for control implementation efforts.

This methodology does not support the idea of calculating exploitation probability numbers or annual loss expectancy values. The criticalities of the risks are determined by the team members’ experience. The author of this methodology (Thomas Peltier) believes that trying to use mathematical formulas for the calculation of risk is too confusing and time consuming. The goal is to keep the scope of the assessment small and the assessment processes simple to allow for efficiency and cost effectiveness.

Another methodology called OCTAVE (Operationally Critical Threat, Asset, and Vulnerability Evaluation) was created by Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute. It is a methodology that is intended to be used in situations where people manage and direct the risk evaluation for information security within their company. This places the people who work inside the organization in the power positions as being able to make the decisions regarding what is the best approach for evaluating the security of their organization. This relies on the idea that the people working in these environments best understand what is needed and what kind of risks they are facing. The individuals who make up the risk assessment team go through rounds of facilitated workshops. The facilitator helps the team members understand the risk methodology and how to apply it to the vulnerabilities and threats identified within their specific business units. It stresses a self-directed team approach. The scope of an OCTAVE assessment is usually very wide compared to the more focused approach of FRAP. Where FRAP would be used to assess a system or application, OCTAVE would be used to assess all systems, applications, and business processes within the organization.

While NIST, FRAP, and OCTAVE methodologies focus on IT security threats and information security risks, AS/NZS ISO 31000 takes a much broader approach to risk management. This Australian and New Zealand methodology can be used to understand a company’s financial, capital, human safety, and business decisions risks. Although it can be used to analyze security risks, it was not created specifically for this purpose. This risk methodology is more focused on the health of a company from a business point of view, not security.

If we need a risk methodology that is to be integrated into our security program, we can use one that was previously mentioned within the “ISO/IEC 27000 Series” section earlier in the chapter. As a reminder, ISO/IEC 27005 is an international standard for how risk management should be carried out in the framework of an information security management system (ISMS). So where the NIST risk methodology is mainly focused on IT and operations, this methodology deals with IT and the softer security issues (documentation, personnel security, training, etc.). This methodology is to be integrated into an organizational security program that addresses all of the security threats an organization could be faced with.

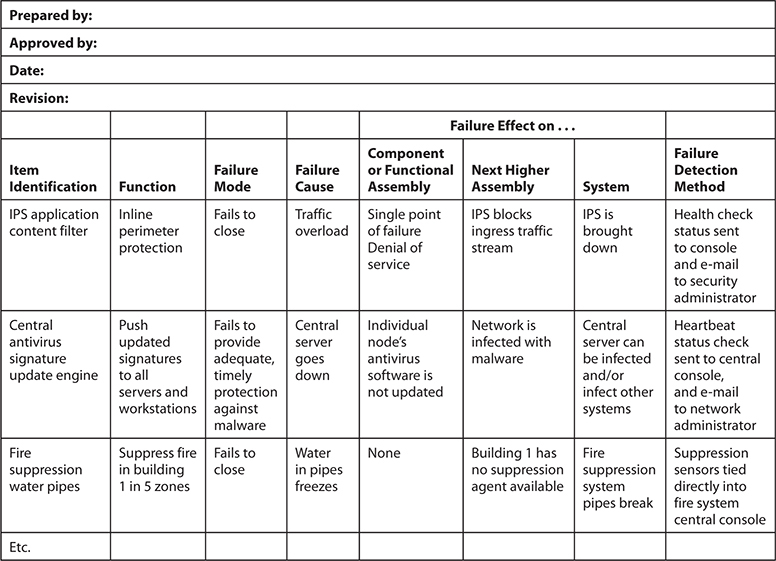

Failure Modes and Effect Analysis (FMEA) is a method for determining functions, identifying functional failures, and assessing the causes of failure and their failure effects through a structured process. FMEA is commonly used in product development and operational environments. The goal is to identify where something is most likely going to break and either fix the flaws that could cause this issue or implement controls to reduce the impact of the break. For example, you might choose to carry out an FMEA on your organization’s network to identify single points of failure. These single points of failure represent vulnerabilities that could directly affect the productivity of the network as a whole. You would use this structured approach to identify these issues (vulnerabilities), assess their criticality (risk), and identify the necessary controls that should be put into place (reduce risk).

The FMEA methodology uses failure modes (how something can break or fail) and effects analysis (impact of that break or failure). The application of this process to a chronic failure enables the determination of where exactly the failure is most likely to occur. Think of it as being able to look into the future and locate areas that have the potential for failure and then applying corrective measures to them before they do become actual liabilities.

By following a specific order of steps, the best results can be maximized for an FMEA:

1. Start with a block diagram of a system or control.

2. Consider what happens if each block of the diagram fails.

3. Draw up a table in which failures are paired with their effects and an evaluation of the effects.

4. Correct the design of the system, and adjust the table until the system is not known to have unacceptable problems.

5. Have several engineers review the Failure Modes and Effect Analysis.

Table 1-6 is an example of how an FMEA can be carried out and documented. Although most companies will not have the resources to do this level of detailed work for every system and control, it can be carried out on critical functions and systems that can drastically affect the company.

FMEA was first developed for systems engineering. Its purpose is to examine the potential failures in products and the processes involved with them. This approach proved to be successful and has been more recently adapted for use in evaluating risk management priorities and mitigating known threat vulnerabilities.

FMEA is used in assurance risk management because of the level of detail, variables, and complexity that continues to rise as corporations understand risk at more granular levels. This methodical way of identifying potential pitfalls is coming into play more as the need for risk awareness—down to the tactical and operational levels—continues to expand.

Table 1-6 How an FMEA Can Be Carried Out and Documented

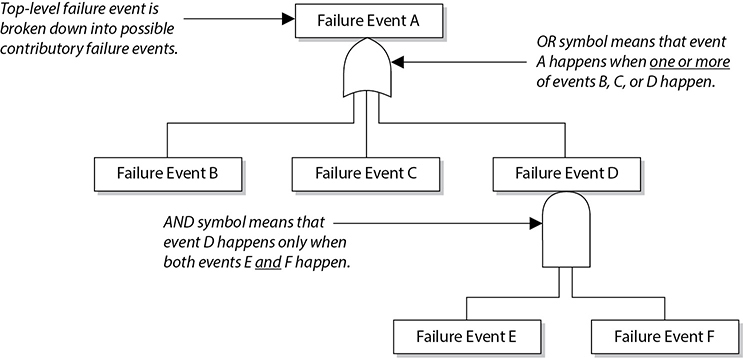

While FMEA is most useful as a survey method to identify major failure modes in a given system, the method is not as useful in discovering complex failure modes that may be involved in multiple systems or subsystems. A fault tree analysis usually proves to be a more useful approach to identifying failures that can take place within more complex environments and systems. Fault trees are similar to the attack trees we discussed earlier and follow this general process. First, an undesired effect is taken as the root or top event of a tree of logic. Then, each situation that has the potential to cause that effect is added to the tree as a series of logic expressions. Fault trees are then labeled with actual numbers pertaining to failure probabilities. This is typically done by using computer programs that can calculate the failure probabilities from a fault tree.

Figure 1-14 shows a simplistic fault tree and the different logic symbols used to represent what must take place for a specific fault event to occur.

When setting up the tree, you must accurately list all the threats or faults that can occur within a system. The branches of the tree can be divided into general categories, such as physical threats, networks threats, software threats, Internet threats, and component failure threats. Then, once all possible general categories are in place, you can trim them and effectively prune the branches from the tree that won’t apply to the system in question. In general, if a system is not connected to the Internet by any means, remove that general branch from the tree.

Some of the most common software failure events that can be explored through a fault tree analysis are the following:

• False alarms

• Insufficient error handling

• Sequencing or order

• Incorrect timing outputs

• Valid but not expected outputs

Figure 1-14 Fault tree and logic components

Of course, because of the complexity of software and heterogeneous environments, this is a very small sample list.

Just in case you do not have enough risk assessment methodologies to choose from, you can also look at CRAMM (Central Computing and Telecommunications Agency Risk Analysis and Management Method), which was created by the United Kingdom, and its automated tools are sold by Siemens. It works in three distinct stages: define objectives, assess risks, and identify countermeasures. It is really not fair to call it a unique methodology, because it follows the basic structure of any risk methodology. It just has everything (questionnaires, asset dependency modeling, assessment formulas, compliancy reporting) in automated tool format.

Similar to the “Security Frameworks” section that covered things such as ISO/IEC 27000, CMMI, COBIT, COSO IC, Zachman Framework, SABSA, ITIL, NIST SP 800-53, and Six Sigma, this section on risk methodologies could at first take seem like another list of confusing standards and guidelines. Remember that the methodologies have a lot of overlapping similarities because each one has the specific goal of identifying things that could hurt the organization (vulnerabilities and threats) so that those things can be addressed (risk reduced). What make these methodologies different from each other are their unique approaches and focuses. If you need to deploy an organization-wide risk management program and integrate it into your security program, you should follow the ISO/IEC 27005 or OCTAVE methods. If you need to focus just on IT security risks during your assessment, you can follow NIST SP 800-30. If you have a limited budget and need to carry out a focused assessment on an individual system or process, you can follow the Facilitated Risk Analysis Process. If you really want to dig into the details of how a security flaw within a specific system could cause negative ramifications, you could use Failure Modes and Effect Analysis or fault tree analysis. If you need to understand your company’s business risks, then you can follow the AS/NZS ISO 31000 approach.

So up to this point, we have accomplished the following items:

• Developed a risk management policy

• Developed a risk management team

• Identified company assets to be assessed

• Calculated the value of each asset

• Identified the vulnerabilities and threats that can affect the identified assets

• Chose a risk assessment methodology that best fits our needs

The next thing we need to figure out is if our risk analysis approach should be quantitative or qualitative in nature, which we will cover in the following section.

EXAM TIP A risk assessment is used to gather data. A risk analysis examines the gathered data to produce results that can be acted upon.

Risk Analysis Approaches

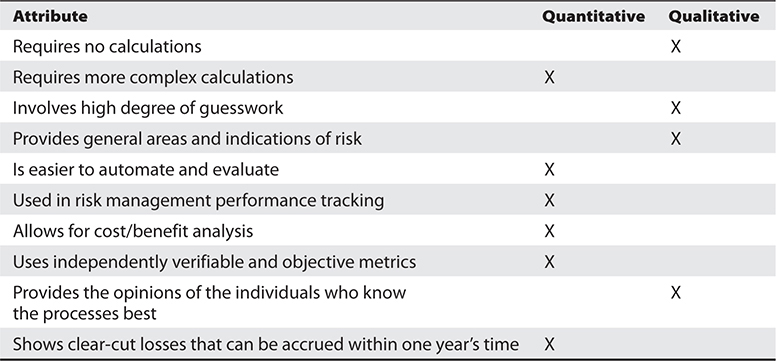

The two approaches to risk analysis are quantitative and qualitative. A quantitative risk analysis is used to assign monetary and numeric values to all elements of the risk analysis process. Each element within the analysis (asset value, threat frequency, severity of vulnerability, impact damage, safeguard costs, safeguard effectiveness, uncertainty, and probability items) is quantified and entered into equations to determine total and residual risks. It is more of a scientific or mathematical approach to risk analysis compared to qualitative. A qualitative risk analysis uses a “softer” approach to the data elements of a risk analysis. It does not quantify that data, which means that it does not assign numeric values to the data so that it can be used in equations. As an example, the results of a quantitative risk analysis could be that the organization is at risk of losing $100,000 if a buffer overflow were exploited on a web server, $25,000 if a database were compromised, and $10,000 if a file server were compromised. A qualitative risk analysis would not present these findings in monetary values, but would assign ratings to the risks, as in Red, Yellow, and Green.

A quantitative analysis uses risk calculations that attempt to predict the level of monetary losses and the probability for each type of threat. Qualitative analysis does not use calculations. Instead, it is more opinion and scenario based and uses a rating system to relay the risk criticality levels.

Quantitative and qualitative approaches have their own pros and cons, and each applies more appropriately to some situations than others. Company management and the risk analysis team, and the tools they decide to use, will determine which approach is best.

In the following sections we will dig into the depths of quantitative analysis and then revisit the qualitative approach. We will then compare and contrast their attributes.

Automated Risk Analysis Methods

Collecting all the necessary data that needs to be plugged into risk analysis equations and properly interpreting the results can be overwhelming if done manually. Several automated risk analysis tools on the market can make this task much less painful and, hopefully, more accurate. The gathered data can be reused, greatly reducing the time required to perform subsequent analyses. The risk analysis team can also print reports and comprehensive graphs to present to management.

EXAM TIP Remember that vulnerability assessments are different from risk assessments. A vulnerability assessment just finds the vulnerabilities (the holes). A risk assessment calculates the probability of the vulnerabilities being exploited and the associated business impact.

The objective of these tools is to reduce the manual effort of these tasks, perform calculations quickly, estimate future expected losses, and determine the effectiveness and benefits of the security countermeasures chosen. Most automatic risk analysis products port information into a database and run several types of scenarios with different parameters to give a panoramic view of what the outcome will be if different threats come to bear. For example, after such a tool has all the necessary information inputted, it can be rerun several times with different parameters to compute the potential outcome if a large fire were to take place; the potential losses if a virus were to damage 40 percent of the data on the main file server; how much the company would lose if an attacker were to steal all the customer credit card information held in three databases; and so on. Running through the different risk possibilities gives a company a more detailed understanding of which risks are more critical than others, and thus which ones to address first.

Steps of a Quantitative Risk Analysis

Recapping the previous sections in this chapter, we have already carried out our risk assessment, which is the process of gathering data for a risk analysis. We have identified the assets that are to be assessed, associated a value to each asset, and identified the vulnerabilities and threats that could affect these assets. Now we need to carry out the risk analysis portion, which means that we need to figure out how to interpret all the data that was gathered during the assessment.

If we choose to carry out a quantitative analysis, then we are going to use mathematical equations for our data interpretation process. The most common equations used for this purpose are the single loss expectancy (SLE) and the annual loss expectancy (ALE).

The SLE is a dollar amount that is assigned to a single event that represents the company’s potential loss amount if a specific threat were to take place. The equation is laid out as follows:

Asset Value × Exposure Factor (EF) = SLE

The exposure factor (EF) represents the percentage of loss a realized threat could have on a certain asset. For example, if a data warehouse has the asset value of $150,000, it can be estimated that if a fire were to occur, 25 percent of the warehouse would be damaged, in which case the SLE would be $37,500:

Asset Value ($150,000) × Exposure Factor (25%) = $37,500

This tells us that the company could potentially lose $37,500 if a fire were to take place. But we need to know what our annual potential loss is, since we develop and use our security budgets on an annual basis. This is where the ALE equation comes into play. The ALE equation is as follows:

SLE × Annualized Rate of Occurrence (ARO) = ALE

The annualized rate of occurrence (ARO) is the value that represents the estimated frequency of a specific threat taking place within a 12-month timeframe. The range can be from 0.0 (never) to 1.0 (once a year) to greater than 1 (several times a year), and anywhere in between. For example, if the probability of a fire taking place and damaging our data warehouse is once every 10 years, the ARO value is 0.1.

So, if a fire taking place within a company’s data warehouse facility can cause $37,500 in damages, and the frequency (or ARO) of a fire taking place has an ARO value of 0.1 (indicating once in 10 years), then the ALE value is $3,750 ($37,500 × 0.1 = $3,750).

The ALE value tells the company that if it wants to put in controls to protect the asset (warehouse) from this threat (fire), it can sensibly spend $3,750 or less per year to provide the necessary level of protection. Knowing the real possibility of a threat and how much damage, in monetary terms, the threat can cause is important in determining how much should be spent to try and protect against that threat in the first place. It would not make good business sense for the company to spend more than $3,750 per year to protect itself from this threat.

Now that we have all these numbers, what do we do with them? Let’s look at the example in Table 1-7, which shows the outcome of a quantitative risk analysis. With this data, the company can make intelligent decisions on what threats must be addressed first because of the severity of the threat, the likelihood of it happening, and how much could be lost if the threat were realized. The company now also knows how much money it should spend to protect against each threat. This will result in good business decisions, instead of just buying protection here and there without a clear understanding of the big picture. Because the company has a risk of losing up to $6,500 if data is corrupted by virus infiltration, up to this amount of funds can be earmarked toward providing antivirus software and methods to ensure that a virus attack will not happen.

When carrying out a quantitative analysis, some people mistakenly think that the process is purely objective and scientific because data is being presented in numeric values. But a purely quantitative analysis is hard to achieve because there is still some subjectivity when it comes to the data. How do we know that a fire will only take place once every 10 years? How do we know that the damage from a fire will be 25 percent of the value of the asset? We don’t know these values exactly, but instead of just pulling them out of thin air, they should be based upon historical data and industry experience. In quantitative risk analysis, we can do our best to provide all the correct information, and by doing so we will come close to the risk values, but we cannot predict the future and how much the future will cost us or the company.

Table 1-7 Breaking Down How SLE and ALE Values Are Used

Results of a Quantitative Risk Analysis

The risk analysis team should have clearly defined goals. The following is a short list of what generally is expected from the results of a risk analysis:

• Monetary values assigned to assets

• Comprehensive list of all significant threats

• Probability of the occurrence rate of each threat

• Loss potential the company can endure per threat in a 12-month time span

• Recommended controls

Although this list looks short, there is usually an incredible amount of detail under each bullet item. This report will be presented to senior management, which will be concerned with possible monetary losses and the necessary costs to mitigate these risks. Although the reports should be as detailed as possible, there should be executive abstracts so senior management can quickly understand the overall findings of the analysis.

Qualitative Risk Analysis

Another method of risk analysis is qualitative, which does not assign numbers and monetary values to components and losses. Instead, qualitative methods walk through different scenarios of risk possibilities and rank the seriousness of the threats and the validity of the different possible countermeasures based on opinions. (A wide-sweeping analysis can include hundreds of scenarios.) Qualitative analysis techniques include judgment, best practices, intuition, and experience. Examples of qualitative techniques to gather data are Delphi, brainstorming, storyboarding, focus groups, surveys, questionnaires, checklists, one-on-one meetings, and interviews. The risk analysis team will determine the best technique for the threats that need to be assessed, as well as the culture of the company and individuals involved with the analysis.

The team that is performing the risk analysis gathers personnel who have experience and education on the threats being evaluated. When this group is presented with a scenario that describes threats and loss potential, each member responds with their gut feeling and experience on the likelihood of the threat and the extent of damage that may result. This group explores a scenario of each identified vulnerability and how it would be exploited. The “expert” in the group, who is most familiar with this type of threat, should review the scenario to ensure it reflects how an actual threat would be carried out. Safeguards that would diminish the damage of this threat are then evaluated, and the scenario is played out for each safeguard. The exposure possibility and loss possibility can be ranked as high, medium, or low on a scale of 1 to 5 or 1 to 10.

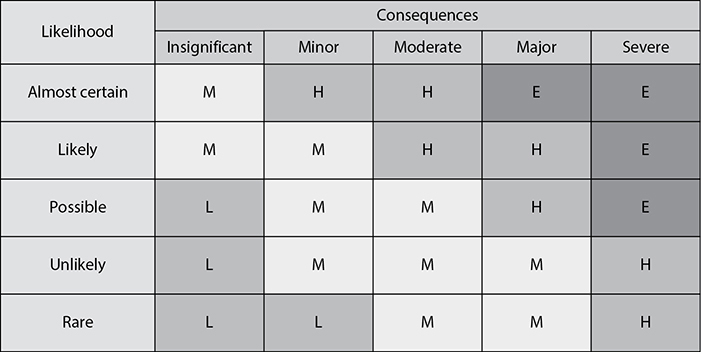

A common qualitative risk matrix is shown in Figure 1-15. Once the selected personnel rank the possibility of a threat happening, the loss potential, and the advantages of each safeguard, this information is compiled into a report and presented to management to help it make better decisions on how best to implement safeguards into the environment. The benefits of this type of analysis are that communication must happen among team members to rank the risks, evaluate the safeguard strengths, and identify weaknesses, and the people who know these subjects the best provide their opinions to management.

Let’s look at a simple example of a qualitative risk analysis.

The risk analysis team presents a scenario explaining the threat of a hacker accessing confidential information held on the five file servers within the company. The risk analysis team then distributes the scenario in a written format to a team of five people (the IT manager, database administrator, application programmer, system operator, and operational manager), who are also given a sheet to rank the threat’s severity, loss potential, and each safeguard’s effectiveness, with a rating of 1 to 5, 1 being the least severe, effective, or probable. Table 1-8 shows the results.

Figure 1-15 Qualitative risk matrix: likelihood vs. consequences (impact)

Table 1-8 Example of a Qualitative Analysis

This data is compiled and inserted into a report and presented to management. When management is presented with this information, it will see that its staff (or a chosen set) feels that purchasing a firewall will protect the company from this threat more than purchasing an intrusion detection system or setting up a honeypot system.

This is the result of looking at only one threat, and management will view the severity, probability, and loss potential of each threat so it knows which threats cause the greatest risk and should be addressed first.

Table 1-9 Quantitative vs. Qualitative Characteristics

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

Each method has its advantages and disadvantages, some of which are outlined in Table 1-9 for purposes of comparison.

The risk analysis team, management, risk analysis tools, and culture of the company will dictate which approach—quantitative or qualitative—should be used. The goal of either method is to estimate a company’s real risk and to rank the severity of the threats so the correct countermeasures can be put into place within a practical budget.

Table 1-9 refers to some of the positive aspects of the quantitative and qualitative approaches. However, not everything is always easy. In deciding to use either a quantitative or qualitative approach, the following points might need to be considered.

Quantitative Cons:

• Calculations can be complex. Can management understand how these values were derived?

• Without automated tools, this process is extremely laborious.

• More preliminary work is needed to gather detailed information about the environment.

• Standards are not available. Each vendor has its own way of interpreting the processes and their results.

Qualitative Cons:

• The assessments and results are subjective and opinion based.

• Eliminates the opportunity to create a dollar value for cost/benefit discussions.

• Hard to develop a security budget from the results because monetary values are not used.

• Standards are not available. Each vendor has its own way of interpreting the processes and their results.

NOTE Since a purely quantitative assessment is close to impossible and a purely qualitative process does not provide enough statistical data for financial decisions, these two risk analysis approaches can be used in a hybrid approach. Quantitative evaluation can be used for tangible assets (monetary values), and a qualitative assessment can be used for intangible assets (priority values).

Protection Mechanisms

The next step is to identify the current security mechanisms and evaluate their effectiveness.

This section addresses identifying and choosing the right countermeasures for computer systems. It gives the best attributes to look for and the different cost scenarios to investigate when comparing different types of countermeasures. The end product of the analysis of choices should demonstrate why the selected control is the most advantageous to the company.

NOTE The terms control, countermeasure, safeguard, security mechanism, and protection mechanism are synonymous in the context of information systems security. We use them interchangeably.

Control Selection

A security control must make good business sense, meaning it is cost effective (its benefit outweighs its cost). This requires another type of analysis: a cost/benefit analysis. A commonly used cost/benefit calculation for a given safeguard (control) is

(ALE before implementing safeguard) – (ALE after implementing safeguard) – (annual cost of safeguard) = value of safeguard to the company

For example, if the ALE of the threat of a hacker bringing down a web server is $12,000 prior to implementing the suggested safeguard, and the ALE is $3,000 after implementing the safeguard, while the annual cost of maintenance and operation of the safeguard is $650, then the value of this safeguard to the company is $8,350 each year.

The cost of a countermeasure is more than just the amount filled out on the purchase order. The following items should be considered and evaluated when deriving the full cost of a countermeasure:

• Product costs

• Design/planning costs

• Implementation costs

• Environment modifications

• Compatibility with other countermeasures

• Maintenance requirements

• Testing requirements

• Repair, replacement, or update costs

• Operating and support costs

• Effects on productivity

• Subscription costs

• Extra man-hours for monitoring and responding to alerts

Many companies have gone through the pain of purchasing new security products without understanding that they will need the staff to maintain those products. Although tools automate tasks, many companies were not even carrying out these tasks before, so they do not save on man-hours, but many times require more hours. For example, Company A decides that to protect many of its resources, purchasing an IDS is warranted. So, the company pays $5,500 for an IDS. Is that the total cost? Nope. This software should be tested in an environment that is segmented from the production environment to uncover any unexpected activity. After this testing is complete and the security group feels it is safe to insert the IDS into its production environment, the security group must install the monitoring management software, install the sensors, and properly direct the communication paths from the sensors to the management console. The security group may also need to reconfigure the routers to redirect traffic flow, and it definitely needs to ensure that users cannot access the IDS management console. Finally, the security group should configure a database to hold all attack signatures and then run simulations.

Costs associated with an IDS alert response should most definitely be considered. Now that Company A has an IDS in place, security administrators may need additional alerting equipment such as smartphones. And then there are the time costs associated with a response to an IDS event.

Anyone who has worked in an IT group knows that some adverse reaction almost always takes place in this type of scenario. Network performance can take an unacceptable hit after installing a product if it is an inline or proactive product. Users may no longer be able to access the Unix server for some mysterious reason. The IDS vendor may not have explained that two more service patches are necessary for the whole thing to work correctly. Staff time will need to be allocated for training and to respond to all of the alerts (true or false) the new IDS sends out.

So, for example, the cost of this countermeasure could be $23,500 for the product and licenses; $2,500 for training; $3,400 for testing; $2,600 for the loss in user productivity once the product is introduced into production; and $4,000 in labor for router reconfiguration, product installation, troubleshooting, and installation of the two service patches. The real cost of this countermeasure is $36,000. If our total potential loss was calculated at $9,000, we went over budget by 300 percent when applying this countermeasure for the identified risk. Some of these costs may be hard or impossible to identify before they are incurred, but an experienced risk analyst would account for many of these possibilities.

Security Control Assessment

The risk assessment team must evaluate the security controls’ functionality and effectiveness. When selecting a security control, some attributes are more favorable than others. Table 1-10 lists and describes attributes that should be considered before purchasing and committing to a security control.

Table 1-10 Characteristics to Consider When Assessing Security Controls

Security controls can provide deterrence attributes if they are highly visible. This tells potential evildoers that adequate protection is in place and that they should move on to an easier target. Although the control may be highly visible, attackers should not be able to discover the way it works, thus enabling them to attempt to modify it, or know how to get around the protection mechanism. If users know how to disable the antivirus program that is taking up CPU cycles or know how to bypass a proxy server to get to the Internet without restrictions, they will do so.

Total Risk vs. Residual Risk

The reason a company implements countermeasures is to reduce its overall risk to an acceptable level. As stated earlier, no system or environment is 100 percent secure, which means there is always some risk left over to deal with. This is called residual risk.

Residual risk is different from total risk, which is the risk a company faces if it chooses not to implement any type of safeguard. A company may choose to take on total risk if the cost/benefit analysis results indicate this is the best course of action. For example, if there is a small likelihood that a company’s web servers can be compromised and the necessary safeguards to provide a higher level of protection cost more than the potential loss in the first place, the company will choose not to implement the safeguard, choosing to deal with the total risk.

There is an important difference between total risk and residual risk and which type of risk a company is willing to accept. The following are conceptual formulas:

threats × vulnerability × asset value = total risk (threats × vulnerability × asset value) × controls gap = residual risk

You may also see these concepts illustrated as the following:

total risk – countermeasures = residual risk

NOTE The previous formulas are not constructs you can actually plug numbers into. They are instead used to illustrate the relation of the different items that make up risk in a conceptual manner. This means no multiplication or mathematical functions actually take place. It is a means of understanding what items are involved when defining either total or residual risk.

During a risk assessment, the threats and vulnerabilities are identified. The possibility of a vulnerability being exploited is multiplied by the value of the assets being assessed, which results in the total risk. Once the controls gap (protection the control cannot provide) is factored in, the result is the residual risk. Implementing countermeasures is a way of mitigating risks. Because no company can remove all threats, there will always be some residual risk. The question is what level of risk the company is willing to accept.

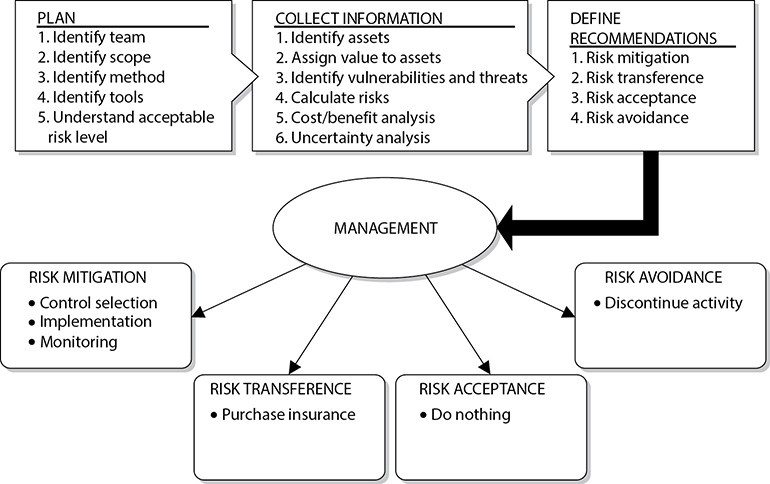

Handling Risk

Once a company knows the amount of total and residual risk it is faced with, it must decide how to handle it. Risk can be dealt with in four basic ways: transfer it, avoid it, reduce it, or accept it.

Many types of insurance are available to companies to protect their assets. If a company decides the total risk is too high to gamble with, it can purchase insurance, which would transfer the risk to the insurance company.

If a company decides to terminate the activity that is introducing the risk, this is known as risk avoidance. For example, if a company allows employees to use instant messaging (IM), there are many risks surrounding this technology. The company could decide not to allow any IM activity by employees because there is not a strong enough business need for its continued use. Discontinuing this service is an example of risk avoidance.

Another approach is risk mitigation, where the risk is reduced to a level considered acceptable enough to continue conducting business. The implementation of firewalls, training, and intrusion/detection protection systems or other control types represent types of risk mitigation efforts.

The last approach is to accept the risk, which means the company understands the level of risk it is faced with, as well as the potential cost of damage, and decides to just live with it and not implement the countermeasure. Many companies will accept risk when the cost/benefit ratio indicates that the cost of the countermeasure outweighs the potential loss value.

A crucial issue with risk acceptance is understanding why this is the best approach for a specific situation. Unfortunately, today many people in organizations are accepting risk and not understanding fully what they are accepting. This usually has to do with the relative newness of risk management in the security field and the lack of education and experience in those personnel who make risk decisions. When business managers are charged with the responsibility of dealing with risk in their department, most of the time they will accept whatever risk is put in front of them because their real goals pertain to getting a project finished and out the door. They don’t want to be bogged down by this silly and irritating security stuff.

Risk acceptance should be based on several factors. For example, is the potential loss lower than the countermeasure? Can the organization deal with the “pain” that will come with accepting this risk? This second consideration is not purely a cost decision, but may entail non cost issues surrounding the decision. For example, if we accept this risk, we must add three more steps in our production process. Does that make sense for us? Or if we accept this risk, more security incidents may arise from it, and are we prepared to handle those?

The individual or group accepting risk must also understand the potential visibility of this decision. Let’s say a company has determined that it does not need to protect customers’ first names, but it does have to protect other items like Social Security numbers, account numbers, and so on. So these current activities are in compliance with the regulations and laws, but what if your customers find out you are not properly protecting their names and they associate such things with identity fraud because of their lack of education on the matter? The company may not be able to handle this potential reputation hit, even if it is doing all it is supposed to be doing. Perceptions of a company’s customer base are not always rooted in fact, but the possibility that customers will move their business to another company is a potential fact your company must comprehend.

Figure 1-16 How a risk management program can be set up

Figure 1-16 shows how a risk management program can be set up, which ties together all the concepts covered in this section.

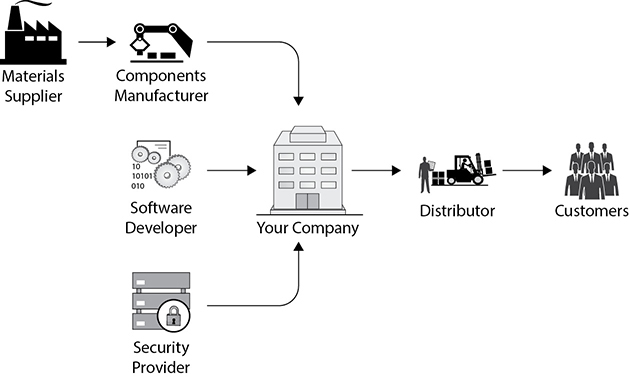

Supply Chain Risk Management

Many organizations fail to consider their supply chain when managing risk, despite the fact that it often presents a convenient and easier back door to an attacker. So what is a supply chain anyway? A supply chain is a sequence of suppliers involved in delivering some product. If your company manufactures laptops, your supply chain will include the vendor that supplies your video cards. It will also include whoever makes the integrated circuits that go on those cards as well as the supplier of the raw chemicals that are involved in that process. The supply chain also includes suppliers of services, such as the company that maintains the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems needed to keep your assembly lines running.

The various organizations that make up your supply chain will have a different outlook on security than you do. For one thing, their threat modeling will include different threats than yours. Why would a criminal looking to steal credit card information target an HVAC service provider? This is exactly what happened in 2013 when Target had over 40 million credit cards compromised. Target had done a reasonable job at securing its perimeter, but not its internal networks. The attacker, unable (or maybe just unwilling) to penetrate Target’s outer shell head-on, decided to exploit the vulnerable network of one of Target’s HVAC service providers and steal its credentials. Armed with these, the thieves were able to gain access to the point of sale terminals and, from there, the credit card information.

The basic processes you’ll need to manage risk in your supply chain are the same ones you use in the rest of your risk management program. The differences are mainly in what you look at (that is, the scope of your assessments) and what you can do about it (legally and contractually). A good resource to help integrate supply chain risk into your risk management program is NIST SP 800-161, “Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Federal Information Systems and Organizations.”

One of the first things you’ll need to do is to create a supply chain map for your organization. This is essentially a network diagram of who supplies what to whom down to your ultimate customers. Figure 1-17 depicts a simplified systems integrator company (“Your Company”). It has a hardware components manufacturer that supplies it hardware and is, in turn, supplied by a materials producer. Your Company receives software from a developer and receives managed security from an external service provider. The hardware and software components are integrated and configured into Your Company’s product, which is then shipped to its distributor and on to its customers. In this example, the company has four suppliers on which to base its supply chain risk assessment. It is also considered a supplier to its distributor.

Figure 1-17 Simplified supply chain

Upstream and Downstream Suppliers

Suppliers are “upstream” from your company if they supply materials, goods, or services to your company and your company uses those in turn to provide whatever it is that it supplies to others. The core vulnerability that exists in these supply arrangements is that you could allow untrusted hardware, software, or services into your organization or products, where they could cause security problems. The Greeks used this to their advantage against the Trojans.

Conversely, your company may be upstream from others in the same supply chain. These would be your company’s downstream suppliers. While it may be tempting to think that you should be concerned only about supply chain security upstream, those who follow your company in the supply chain may have their own set of upstream requirements for your firm. Furthermore, your customers may not care that a security issue was caused by your downstream distributor; your brand name will be damaged all the same.

Hardware

One of the major supply chain risks is the addition of hardware Trojans to electronic components. A hardware Trojan is an electronic circuit that is added to an existing device in order to compromise its security or provide unauthorized functionality. Depending on the attacker’s access, these mechanisms can be inserted at any stage of the hardware development process (specification, design, fabrication, testing, assembly, or packaging). It is also possible to add them after the hardware is packaged by intercepting shipments in the supply chain. In this case, the Trojan may be noticeable if the device is opened and visually inspected. The earlier hardware Trojans are inserted, the more difficult they are to detect.

Another supply chain risk to hardware is the substitution of counterfeit components. The problems with these clones are many, but from a security perspective one of the most important is that they don’t go through the same quality controls that the real ones do. This leads to lower reliability and abnormal behavior. It could also lead to undetected hardware Trojans (perhaps inserted by the illicit manufacturers themselves). Obviously, using counterfeits could have legal implications and will definitely be a problem when you need customer support from the manufacturer.

Software

Like hardware, third-party software can be Trojaned by an adversary in your supply chain, particularly if it is custom-made for your organization. This could happen if your supplier reuses components (like libraries) developed elsewhere and to which the attacker has access. It can also be done by a malicious insider in the supplier or by a remote attacker who has gained access to the supplier’s software repositories. Failing all that, the software could be intercepted in transit to you, modified, and then sent on its way. This last approach could be made more difficult for the adversary by using code signing or hashes, but it is still possible.

Services

More organizations are outsourcing services to allow them to focus on their core business functions. Companies use hosting companies to maintain websites and e-mail servers, service providers for various telecommunication connections, disaster recovery companies for co-location capabilities, cloud computing providers for infrastructure or application services, developers for software creation, and security companies to carry out vulnerability management. It is important to realize that while you can outsource functionality, you cannot outsource risk. When your company is using these third-party service providers, your company can still be ultimately responsible if something like a data breach takes place. Let’s look at some things an organization should do to reduce its risk when it comes to outsourcing:

• Review the service provider’s security program

• Conduct onsite inspection and interviews

• Review contracts to ensure security and protection levels are agreed upon

• Ensure service level agreements are in place

• Review internal and external audit reports and third-party reviews

• Review references and communicate with former and existing customers

• Review Better Business Bureau reports

• Ensure the service provider has a business continuity plan (BCP) in place

• Implement a nondisclosure agreement (NDA)

• Understand the provider’s legal and regulatory requirements

Service outsourcing is prevalent within organizations today but is commonly forgotten about when it comes to security and compliance requirements. It may be economical to outsource certain functionalities, but if this allows security breaches to take place, it can turn out to be a very costly decision.

Service Level Agreements

A service level agreement (SLA) is a contractual agreement that states that a service provider guarantees a certain level of service. If the service is not delivered at the agreed-upon level (or better), then there are consequences (typically financial) for the service provider. SLAs provide a mechanism to mitigate some of the risk from service providers in the supply chain. For example, an Internet service provider (ISP) may sign an SLA of 99.999 percent (called five nines) uptime to the Internet backbone. That means that the ISP guarantees less than 26 seconds of downtime per month.

Risk Management Frameworks

We have covered a lot of material dealing with risk management in general and risk assessments in particular. By now, you may be asking yourself, “How does this all fit together into an actionable process?” This is where frameworks come to the rescue. The Oxford English Dictionary defines framework as a basic structure underlying a system, concept, or text. By combining this with our earlier definition of risk management, we can define a risk management framework (RMF) as a structured process that allows an organization to identify and assess risk, reduce it to an acceptable level, and ensure that it remains at that level. In essence, an RMF is a structured approach to risk management.

As you might imagine, there is no shortage of RMFs out there. What is important to you as a security professional is to ensure your organization has an RMF that works for you. That being said, there are some frameworks that have enjoyed widespread success and acceptance (see sidebar). You should at least be aware of these, and ideally adopt (and perhaps modify) one of them to fit your particular needs.

In this section, we will focus our discussion on the NIST risk management framework, SP 800-37, Revision 1, “Guide for Applying the Risk Management Framework to Federal Information Systems,” since it incorporates the most important components that you should know as a security professional. It is important to keep in mind, however, that this framework is geared toward federal government entities and may have to be modified to fit your own needs. The NIST RMF outlines the following six-step process of applying the RMF, each of which will be addressed in turn in the following sections:

1. Categorize information system.

2. Select security controls.

3. Implement security controls.

4. Assess security controls.

5. Authorize information system.

6. Monitor security controls.

Categorize Information System

The first step is to identify and categorize the information system. What does this mean? First, you have to identify what you have in terms of systems, subsystems, and boundaries. For example, if you have a customer relationship management (CRM) information system, you need to inventory its components (e.g., software, hardware), any subsystems it may include (e.g., bulk e-mailer, customer analytics), and its boundaries (e.g., interface with the corporate mail system). You also need to know how this system fits into your organization’s business process, how sensitive it is, and who owns it and the data within it. Other questions you may ask are

• How is the information system integrated into the enterprise architecture?

• What types of information are processed, stored, and transmitted by the system?

• Are there regulatory or legal requirements applicable to the information system?

• How is the system interconnected to others?

• What is the criticality of this information system to the business?