Chapter 1. Introduction

The service industry is a significant driver for worldwide economic growth. Guidance on developing and improving mature service practices is a key contributor to improved performance, customer satisfaction, and profitability. The CMMI for Services (CMMI-SVC) model is designed to begin meeting that need.

All CMMI-SVC model practices focus on the activities of the service provider. Seven process areas focus on practices specific to services, addressing capacity and availability management, service continuity, service delivery, incident resolution and prevention, service transition, service system development, and strategic service management processes. The remaining 17 process areas focus on practices that any organization should master to meet its business objectives.

Do You Need CMMI?

CMMI is being adopted by organizations all over the world. These organizations are large and small, government and private industry, and represent industries ranging from financial to health care, manufacturing to software, education to business services. What do all of these organizations have in common?

Do You Have These Common Problems?

Many organizations accept common problems as “normal” and they don’t try to address them or eliminate them. What about your organization? Are you settling for less? Take a look through the following list and see if you have accepted problems that you can solve by adopting CMMI.

• Plans are made, but not necessarily followed.

• Work is not tracked against the plan; plans are not adjusted.

• Expectations and service levels are not consistent; changes to them are not managed.

• Estimates are way off; over-commitment is common.

• When overruns become apparent, a crisis atmosphere develops.

• Most problems are discovered in operations or, worse yet, by the customer.

• Success depends on heroic efforts by competent staff members.

• Repeatability of effective behaviors is questionable.

Even if you’ve accepted that your organization could use something to reduce or eliminate these problems, some service providers reject the idea of using process improvement to address or resolve them. Some mythology has grown up around the idea of using process improvement. You may have heard some of these fallacies.

• I don’t need process improvement; I have good people (or advanced technology, or an experienced manager).

• Process improvement interferes with creativity and introduces bureaucracy.

• Process improvement is useful only in large organizations and costs too much.

• Process improvement hinders agility in fast-moving markets.1

These common misconceptions serve only as excuses for organizations not willing to make the changes needed to move ahead, address their problems, and improve their bottom line.

Another way to look at whether your organization could benefit from CMMI is to think about whether it is often operating in crisis mode. Crisis mode is characterized by the following:

• Staff members working harder and longer

• Staff members moving from team to team

• Service teams lowering expectations to meet delivery deadlines

• Service teams adding more people to meet expectations or deadlines

• Everyone cutting corners

• A hero saving the day

How Does CMMI Help You to Solve These Problems?

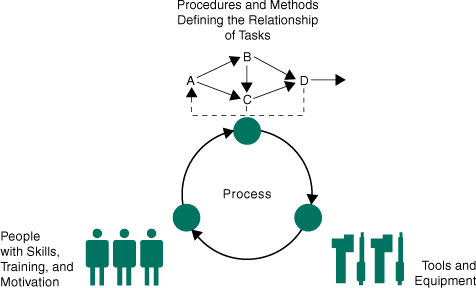

In its research to help organizations to develop and maintain quality products and services, the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) has found several dimensions that an organization can focus on to improve its business. Figure 1.1 illustrates the three critical dimensions that organizations typically focus on: people, procedures and methods, and tools and equipment.

Figure 1.1 The Three Critical Dimensions

What holds everything together? It is the processes used in your organization. Processes allow you to align the way you do business. They allow you to address scalability and provide a way to incorporate knowledge of how to do things better. Processes allow you to leverage your resources and to examine business trends.

This is not to say that people and technology are not important. We are living in a world where technology is changing at an incredible speed. Similarly, people typically work for many companies throughout their careers. We live in a dynamic world. A focus on process provides the infrastructure and stability necessary to deal with an ever-changing world and to maximize the productivity of people and the use of technology to be competitive.

Manufacturing has long recognized the importance of process effectiveness and efficiency. Today, many organizations in manufacturing and service industries recognize the importance of quality processes. Process helps an organization’s workforce to meet business objectives by helping them to work smarter, not harder, and with improved consistency. Effective processes also provide a vehicle for introducing and using new technology in a way that best meets the business objectives of the organization.

The advantage of a process focus is that it complements the emphasis the organization places on both its people and its technology.

• A well-defined process can provide the means to work smarter, not harder. That means using the experience and training of your workforce effectively. It also means shifting the “blame” for problems from people to processes, making the problems easier to address and solve.

• An appropriate process roadmap can help your organization use technology to its best advantage. Technology alone does not guarantee its effective use.

• A disciplined process enables an organization to discover which procedures and methods are most effective and to improve them as results are measured.

CMMI is a suite of products used for process improvement. These products include models, appraisal methods, and training courses.

• The models are descriptions of best practices that can help you achieve your business goals related to cost, schedule, service levels, quality, and so forth. CMMI best practices describe what to do, but not how to do it or who should do it.

• The appraisal methods evaluate an organization’s processes using a CMMI model as a yardstick. SCAMPI (Standard CMMI Appraisal Method for Process Improvement) is the group of SEI appraisal methods used with CMMI models. SCAMPI uses a formalized appraisal process, involves senior management as a sponsor, focuses the appraisal on the sponsor’s business objectives, and observes strict confidentiality and nonattribution of data.

• Training courses support knowledge about the use of CMMI models and appraisal methods.

The SEI has taken the process management premise that the quality of a product (including service) is highly influenced by the quality of the process used to develop and maintain it, and defined CMMs that embody this premise. The belief in this premise is seen worldwide in quality movements, as evidenced by the International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) body of standards.

How Can CMMI Benefit You?

Today, CMMI is an application of the principles introduced almost a century ago to achieve an enduring cycle of process improvement. The value of this process improvement approach has been confirmed over time. Organizations have experienced increased productivity and quality, improved cycle time, and more accurate and predictable schedules and budgets [Gibson 2006].

The benefits of CMMI have been published for years and will continue to be published in the future. (See the SEI website for more information about performance results.)

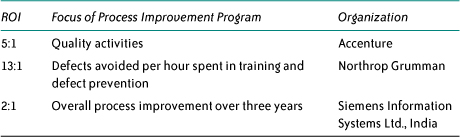

The cost of CMMI adoption is highly variable depending on many factors (e.g., organization size, culture, structure, current processes). Regardless of the investment, history demonstrates a respectable return on investment (ROI).

Example returns on investment at various organizations using CMMI-DEV include those shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Benefits Resulting from the Use of CMMI-DEV

Since the CMMI-SVC model was first released only two short years ago (2009), data on the results of its use are not yet available. We will be collecting ROI data as organizations adopt the CMMI-SVC model and experience the benefits.

See the CMMI website (www.sei.cmu.edu/cmmi/) for the latest information about CMMI adoption, including presentations by those who have adopted CMMI and want to share how they did it.

A Capability Maturity Model (CMM), including CMMI, is a simplified representation of the world. CMMs contain the essential elements of effective processes. These elements are based on the concepts developed by Crosby, Deming, Juran, and Humphrey.

In the 1930s, Walter Shewhart began work in process improvement with his principles of statistical quality control [Shewhart 1931]. These principles were refined by W. Edwards Deming [Deming 1986], Phillip Crosby [Crosby 1979], and Joseph Juran [Juran 1988].

Watts Humphrey, Ron Radice, and others extended these principles further and began applying them to software in their work at IBM and the SEI [Humphrey 1989]. Humphrey’s book, Managing the Software Process, provides a description of the basic principles and concepts on which many of the CMMs are based.

The SEI has taken the process management premise, “the quality of a system or product is highly influenced by the quality of the process used to develop and maintain it,” and defined CMMs that embody this premise. The belief in this premise is seen worldwide in quality movements, as evidenced by the ISO/IEC body of standards.

CMMs focus on improving processes in an organization. They contain the essential elements of effective processes for one or more disciplines and describe an evolutionary improvement path from ad hoc, immature processes to disciplined, mature processes with improved quality and effectiveness.

Like other CMMs, CMMI models provide guidance to use when developing processes. CMMI models are not processes or process descriptions. The actual processes used in an organization depend on many factors, including application domains and organization structure and size. In particular, the process areas of a CMMI model typically do not map one to one with the processes used in your organization.

The SEI created the first CMM designed for software organizations and published it in a book, The Capability Maturity Model: Guidelines for Improving the Software Process [SEI 1995].

Today, CMMI is an application of the principles introduced almost a century ago to this never-ending cycle of process improvement. The value of this process improvement approach has been confirmed over time. Organizations have experienced increased productivity and quality, improved cycle time, and more accurate and predictable schedules and budgets [Gibson 2006].

Evolution of CMMI

The CMM Integration project was formed to sort out the problem of using multiple CMMs. The combination of selected models into a single improvement framework was intended for use by organizations in their pursuit of enterprise-wide process improvement.

Developing a set of integrated models involved more than simply combining existing model materials. Using processes that promote consensus, the CMMI Product Team built a framework that accommodates multiple constellations.

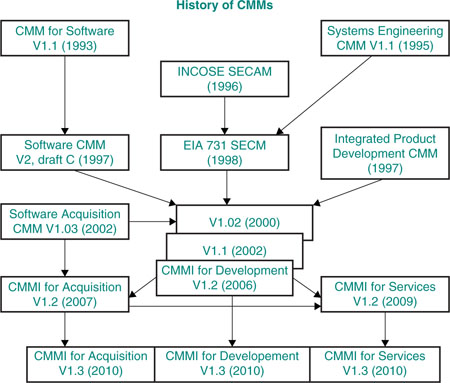

The first model to be developed was the CMMI for Development model (then simply called “CMMI”). Figure 1.2 illustrates the models that led to CMMI Version 1.3.

Figure 1.2 The History of CMMs2

Initially, CMMI was one model that combined three source models: the Capability Maturity Model for Software (SW-CMM) V2.0 draft C, the Systems Engineering Capability Model (SECM) [EIA 2002a], and the Integrated Product Development Capability Maturity Model (IPD-CMM) V0.98.

These three source models were selected because of their successful adoption or promising approach to improving processes in an organization.

The first CMMI model (V1.02) was designed for use by development organizations in their pursuit of enterprise-wide process improvement. It was released in 2000. Two years later Version 1.1 was released, and four years after that, Version 1.2 was released.

By the time Version 1.2 was released, two other CMMI models were being planned. Because of this planned expansion, the name of the first CMMI model had to change to become CMMI for Development and the concept of constellations was created.

The CMMI for Acquisition model was released in 2007. Since it built on the CMMI for Development Version 1.2 model, it also was named Version 1.2. Two years later the CMMI for Services model was released. It built on the other two models and also was named Version 1.2.

In 2008, plans were drawn to begin developing Version 1.3, which would ensure consistency among all three models and improve high maturity material. Version 1.3 of CMMI for Acquisition [Gallagher 2011, SEI 2010b], CMMI for Development [Chrissis 2011, SEI 2010a], and CMMI for Services [Forrester 2011, SEI 2010c] were released in November 2010.

CMMI Framework

The CMMI Framework provides the structure needed to produce CMMI models, training, and appraisal components. To allow the use of multiple models within the CMMI Framework, model components are classified as either common to all CMMI models or applicable to a specific model. The common material is called the “CMMI Model Foundation” or “CMF.”

The components of the CMF are part of every model generated from the CMMI Framework. Those components are combined with material applicable to an area of interest (e.g., acquisition, development, services) to produce a model.

A “constellation” is defined as a collection of CMMI components that are used to construct models, training materials, and appraisal related documents for an area of interest (e.g., services, development, acquisition). The model for the Services constellation is called “CMMI for Services” or “CMMI-SVC.”

CMMI for Services

CMMI-SVC draws on concepts and practices from CMMI and other service-focused standards and models, including the following:

• Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL)

• ISO/IEC 20000: Information Technology—Service Management

• Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (CobiT)

• Information Technology Services Capability Maturity Model (ITSCMM)

Familiarity with these and other service-oriented standards and models is not required to comprehend CMMI-SVC, and this model is not structured in a way that is intended to conform to any of them. However, knowledge of other standards and models can provide a richer understanding of CMMI-SVC.

The CMMI-SVC model covers the activities required to establish, deliver, and manage services. As defined in the CMMI context, a service is an intangible, nonstorable product. The CMMI-SVC model has been developed to be compatible with this broad definition.

CMMI-SVC goals and practices are therefore potentially relevant to any organization concerned with the delivery of services, including enterprises in sectors such as defense, information technology (IT), health care, finance, and transportation. Early users of CMMI-SVC include organizations that deliver services as varied as training, logistics, maintenance, refugee services, lawn care, book shelving, research, consulting, auditing, independent verification and validation, human resources, financial management, health care, and IT services.

The CMMI-SVC model contains practices that cover work management, process management, service establishment, service delivery and support, and supporting processes. The CMMI-SVC model shares a great deal of material with CMMI models in other constellations. Therefore, those who are familiar with another CMMI constellation will find much of the CMMI-SVC content familiar.

When using this model, use professional judgment and common sense to interpret it for your organization. That is, although the process areas described in this model depict behaviors considered best practices for most service providers, all process areas and practices should be interpreted using an in-depth knowledge of CMMI-SVC, organizational constraints, and the business environment.

Organizations interested in evaluating and improving their processes to develop systems for delivering services can use the CMMI-DEV model. This approach is especially recommended for organizations that are already using CMMI-DEV or that must develop and maintain complex systems for delivering services. However, the CMMI-SVC model provides an alternative, streamlined approach to evaluating and improving the development of service systems that can be more appropriate in certain contexts.

Important CMMI-SVC Concepts

The following concepts are particularly significant in the CMMI-SVC model. Although all are defined in the glossary, they each employ words that can cover a range of possible meanings to those from different backgrounds, and so they merit additional discussion to ensure that model material that includes these concepts is not misinterpreted.

Service

The most important of these terms is the word service itself, which the glossary defines as a product that is intangible and nonstorable. While this definition accurately captures the intended scope of meaning for the word service, it does not highlight some of the possible subtleties or misunderstandings of this concept in the CMMI context.

The first point to highlight is that a service is a kind of product, given this definition. Many people routinely think of products and services as two mutually exclusive categories. In CMMI models, however, products and services are not disjoint categories: A service is considered to be a special variety of product. Any reference to products can be assumed to refer to services as well. If you find a need to refer to a category of products that are not services in a CMMI context, you may find it helpful to use the term goods, as in the commonly used and understood phrase “goods and services.” (For historical reasons, portions of CMMI models still use the phrase “products and services” on occasion. However, this usage is always intended to explicitly remind the reader that services are included in the discussion.)

A second possible point of confusion is between services and processes, especially because both terms refer to entities that are by nature intangible and nonstorable, and because both concepts are intrinsically linked. However, in CMMI models, processes are activities, while services are a useful result of performing those activities. For example, an organization that provides training services performs training processes (activities) that are intended to leave the recipients of the training in a more knowledgeable state. This useful state of affairs (i.e., being more knowledgeable) is the service that the training provider delivers or attempts to deliver. If the training processes are performed but the recipients fail to become more knowledgeable (perhaps because the training is poorly designed, or the recipients don’t have some necessary preliminary knowledge), then the service—the useful result—has not actually been delivered. Services are the results of processes (performed as part of a collection of resources), not the processes themselves.

A final possible point of confusion over the meaning of the word service will be apparent to those with a background in information technology, especially those familiar with disciplines such as service-oriented architecture (SOA) or software as a service (SaaS). In a software context, services are typically thought of as methods, components, or building blocks of a larger automated system, rather than as the results produced by that system. In CMMI models, services are useful intangible and nonstorable results delivered through the operation of a service system, which may or may not have any automated components. To completely resolve this possible confusion, an understanding of the service system concept is necessary.

Service System

A service is delivered through the operation of a service system, which the glossary defines as an integrated and interdependent combination of component resources that satisfies service requirements. The use of the word system in service system may suggest to some that service systems are a variety of information technology, and that they must have hardware, software, and other conventional IT components. This interpretation is much too restrictive. While it is possible for some components of a service system to be implemented with information technology, it is also possible to have a service system that uses little or no information technology at all. Even organizations that deliver managed IT services have service systems that encompass more than merely IT components.

In this context, the word system should be interpreted in the broader sense of “a regularly interacting or interdependent group of items forming a unified whole,” a typical dictionary definition. Also, systems created by people usually have an intended unifying purpose, as well as a capability to operate or behave in intended ways. Consider a package delivery system, a health care system, or an education system as examples of service systems with a wide variety of integrated and interdependent component resources.

Some may still have trouble with this interpretation because they may feel that the way they deliver services is not systematic, does not involve identifiable “components,” or is too small or difficult to view through the lens of a systems perspective. While this difficulty may in some cases be true for service provider organizations with relatively immature practices, part of the difficulty may also be traced to an overly narrow interpretation of the word resources in the definition of service system.

The full extent of a service system encompasses everything required for service delivery, including work products, processes, tools, facilities, consumable items, and human resources. Some of these resources may belong to customers or suppliers, and some may be transient (in the sense that they are only part of the service system for a limited time). But all of these resources become part of a service system if they are needed in some way to enable service delivery.

Because of this broad range of included resource types and the relationships among them, a service system can be something large and complex, with extensive facilities and tangible components (e.g., a service system for health care or for transportation). Alternatively, a service system could be something consisting primarily of people and processes (e.g., for an independent verification and validation service). Since every service provider organization using the CMMI-SVC model must have at a minimum both people and process resources, they should be able to apply the service system concept successfully.

Service providers who are not used to thinking of their methods, tools, and personnel for service delivery from a broad systems perspective may need to expend some effort to reframe their concept of service delivery to accommodate this perspective. The benefits of doing so are great, however, because critical and otherwise unnoticed resources and dependencies among resources will become visible for the first time. This insight will enable the service provider organization to effectively improve its operations over time without being caught by surprises or wasting resources on incompletely addressing a problem.

Service Agreement

A service agreement is the foundation of the joint understanding between a service provider and a customer of what to expect from their mutual relationship. The glossary defines a service agreement as a binding, written record of a promised exchange of value between a service provider and a customer. Service agreements can appear in a wide variety of forms, ranging from simple posted menus of services and their prices, to tickets or signs with fine print that refer to terms and conditions described elsewhere, to complex multipart documents that are included as part of legal contracts. Whatever they may contain, it is essential that service agreements be recorded in a form that both the service provider and the customer can access and understand so that misunderstandings are minimized.

The “promised exchange of value” implies that each party to the agreement commits to providing the other party or parties with something they need or want. A common situation is for the service provider to deliver needed services and for the customer to pay money in return, but many other types of arrangements are possible. For example, an operating level agreement (OLA) between organizations in the same enterprise may require only that the customer organization notify the service provider organization when certain services are needed. Service agreements for public services provided by governments, municipal agencies, and nonprofit organizations may simply document what services are available, and identify what steps end users must follow to get those services. In some cases, the only thing the service provider needs or wants from the customer or end user is specific information required to enable service delivery.

See the glossary for additional discussion of the terms service agreement, service level agreement, customer, and end user.

Service Request

Even given a service agreement, customers and end users must be able to notify the service provider of their needs for specific instances of service delivery. In the CMMI-SVC model, these notifications are called “service requests,” and they can be communicated in every conceivable way, including face-to-face encounters, phone calls, all varieties of written media, and even nonverbal signals (e.g., pressing a button to call a bus to a bus stop).

However it is communicated, a service request identifies one or more desired services that the request originator expects to fall within the scope of an existing service agreement. These requests are often generated over time by customers and end users as their needs develop. In this sense, service requests are expected intentional actions that are an essential part of service delivery; they are the primary triggering events that cause service delivery to occur. (Of course, it is possible for the originator of a request to be mistaken about whether the request is actually within the scope of agreed services.)

Sometimes specific service requests may be incorporated directly into the service agreements themselves. This incorporation of service requests in the service agreement is often the case for services that are to be performed repeatedly or continuously over time (e.g., a cleaning service with a specific expected cleaning schedule or a network management service that must provide 99.9 percent network availability for the life of the service agreement). Even in these situations, ad hoc service requests may also be generated when needed and the service provider should be prepared to deliver services in response to both types of requests.

Service Incident

Even with the best planning, monitoring, and delivery of services, unintended events may occur that are unwanted. Some instances of service delivery may have lower than expected or lower than acceptable degrees of performance or quality, or may be completely unsuccessful. The CMMI-SVC model refers to these difficulties as “service incidents.” The glossary defines a service incident as an indication of an actual or potential interference with a service. The single word incident is used in place of service incident when the context makes the meaning clear.

Like requests, incidents require some recognition and response by the service provider; but unlike requests, incidents are unintended events, although some types of incidents may be anticipated. Whether or not they are anticipated, incidents must be resolved in some way by the service provider. In some service types and service provider organizations, service requests and incidents are both managed and resolved through common processes, personnel, and tools. The CMMI-SVC model is compatible with this kind of approach, but does not require it, as it is not appropriate for all types of services.

The use of the word potential in the definition of service incident is deliberate and significant; it means that incidents do not always have to involve actual interference with or failure of service delivery. Indications that a service may have been insufficient or unsuccessful are also incidents, as are indications that it may be insufficient or unsuccessful in the future. (Customer complaints are an almost universal example of this type of incident because they are always indications that service delivery may have been inadequate.) This aspect of incidents is often overlooked, but it is important: Failure to address and resolve potential interference with services is likely to lead eventually to actual interference, and possibly to a failure to satisfy service agreements.

Project, Work Group, and Work

CMMI models must often refer to the organizational entities that are at the foundation of process improvement efforts. These entities are focal points in the organization for creating value, managing work, tailoring processes, and conducting appraisals. In CMMI-SVC, these entities are called “work groups,” while in CMMI-DEV and CMMI-ACQ these entities are called “projects.” The glossary defines both terms and their relationship to each other, but it does not explain why two different terms are needed.

Those with prior experience using CMMI-DEV or CMMI-ACQ models, or who routinely think of their work as part of a project-style work arrangement, may wonder why the term project is not sufficient by itself. The CMMI glossary defines a “project” as a managed set of interrelated activities and resources, including people, that delivers one or more products or services to a customer or end user. The definition notes explain that a project has an intended beginning (i.e., project startup) and end, and that it typically operates according to a plan. These are characteristics of a project according to many definitions, so why is there an issue? Why might there be a difficulty with applying terms like project planning or project management in some service provider organizations?

One simple reason is that projects have an intended end as well as an intended beginning; such efforts are focused on accomplishing an objective by a certain time. While some services follow this same pattern, many are delivered over time without an expected end (e.g., typical municipal services, or services from businesses that intend to offer them indefinitely). Service providers in these contexts are naturally reluctant to describe their service delivery work as a project under this definition.

In prior (V1.2) CMMI models, the definition of “project” was deliberately changed to eliminate this limitation (i.e., that projects have a definite or intended end), in part to allow the term to be applied easily to the full range of service types. However, the change raised more questions and objections than it resolved when interpreted by many users (even in some service contexts), and so the limited meaning has been restored in V1.3: Projects now must have an intended end.

For organizations that do not structure their people and other resources into projects with intended ends, or that only do so for a portion of their work, the original problem remains. All of the common CMMI practices are useful whether or not your work is planned to have an intended end, but what can we call a fundamental organizational entity that implements those practices if it is not a project? How can we refer to and apply the practices of process areas such as project planning when we are not discussing a project?

The CMMI V1.3 solution is to introduce some new terms that take advantage of two distinct senses of meaning for the English word project: as a collection of resources (including people), and as a collection of activities performed by people. CMMI-DEV and CMMI-ACQ continue to use the term project for both senses, because this reflects the typical nature of development and acquisition efforts; CMMI-SVC replaces “project” with “work group” (when it refers strictly to a collection of resources including people) or with “work” (when it refers to a collection of activities, or a collection of activities and associated resources). The glossary defines a “work group” as a managed set of people and other resources that delivers one or more products or services to a customer or end user. The definition is silent on the expected lifetime of a work group. Therefore, a project (in the first sense) may be considered a type of work group, one whose work is planned to have an intended end.

Service provider organizations may therefore structure themselves into work groups (without time limits) or projects (with time limits) depending on the nature of the work, and many organizations will do both in different contexts. For example, development of a service system may be performed by a project, whereas service delivery may be performed by a work group.

The glossary also notes that a work group may contain work groups, may span organizational boundaries, and may appear at any level of an organization. It is possible for a work group to be defined by nothing more than those in an organization with a particular common purpose (e.g., all those who perform a particular task), whether or not that group is represented somewhere on an organization chart.

In the end, of course, organizations will use whatever terminology is comfortable, familiar, and useful to them, and the CMMI-SVC model does not require this approach to change. However, all CMMI models need a convenient way to refer clearly to the fundamental groupings of resources that organize work to achieve significant objectives. In contrast to other CMMI models, the CMMI-SVC model uses the term work group rather than project for this limited purpose, and uses the term work for other senses of the word project including combined senses. For example, a “project plan” is called a “work plan” in CMMI-SVC. (In a few cases, the word project is retained in the CMMI-SVC model when it explicitly refers to a true project.)

Consistent with this usage, the titles of some important core process areas are different in CMMI-SVC compared to CMMI-DEV and CMMI-ACQ: Work Planning, Work Monitoring and Control, Integrated Work Management, and Quantitative Work Management (cf. Project Planning, Project Monitoring and Control, Integrated Project Management, and Quantitative Project Management). Despite these differences in terminology in different constellations, Integrated Work Management and Integrated Project Management cover essentially the same material and are considered to be the same core process area in all three CMMI constellations; the same is true for other equivalent process area pairings.

Stakeholder, Customer, and End User

In the model glossary, a stakeholder is defined as a group or individual who is affected by or is in some way accountable for the outcome of an undertaking. Stakeholders include any and all parties with a legitimate interest in the results of service delivery, such as service provider executives, staff members, customers, end users, suppliers, partners, and oversight groups. Remember that any given reference to stakeholders in the model covers all these types of stakeholders, and not just the ones that might be most obvious in the particular context.

The model defines a customer as the party (individual, project, or organization) responsible for accepting the product or for authorizing payment. A customer must also be external to the project that develops (delivers) a product (service), although both the customer and the project may be part of the same larger organization.

While this concept seems clear enough, the glossary includes some ambiguous language about how the term customer can include “other relevant stakeholders” in some contexts, such as customer requirements. While this caveat reflects an accepted legacy usage of the term from earlier versions of CMMI models, it could be potentially confusing in a service context, where the distinction between customers and other stakeholders (especially end users) can be especially significant.

The CMMI for Services model addresses this concern in two ways. First, it avoids the term customer requirements except in those contexts where it refers to the requirements of customers in the narrow sense (those who accept a product or authorize payment). Second, the model relies upon material in the glossary that distinguishes between customers and end users, and that defines the term end user itself. Specifically, the model defines an end user as a party (individual, project, or organization) that ultimately uses a delivered product or receives the benefit of a delivered service. While end users and customers therefore cover distinct roles in service establishment and delivery, both can often be represented by a single party.

For example, a private individual who receives financial services from a bank is probably both the customer and the end user of those services. However, in health care services, the customers often include organizations such as employers and government agencies that negotiate (or dictate) health care plan coverage for the ultimate health care beneficiaries, who are the end users of those services. (Many of these end users may be customers as well, if they have a responsibility to pay for all or part of some services.)

To summarize: It’s important to keep in mind the actual scope of the terms stakeholder, customer, and end user as you review and apply the CMMI for Services model in your unique service context so that you don’t overlook or confuse crucial interactions and interfaces in your service system.