4. Standard Zooms and Primes

ISO 200 • 1/60 sec. • f/2.8 • 63mm

Image-making with the most popular lenses

Standard. That is a word that describes a necessity, the basis against which all else is judged, or around which everything is designed. It makes sense, then, that a large number of the lenses Canon makes belong to two groups dubbed standard primes and standard zooms.

Standard, in the case of lenses, refers to a range of focal lengths that photographers can maximize for the largest amount of image-making. All 19 lenses (as of this writing) in this category offer photographers the most options available in one lens for making great pictures—pictures that vary in focal length but do not deviate much from the familiar human perspective.

The Go-To Lenses

If you recently purchased an EOS Rebel-series camera, you more than likely purchased an entire kit that included an EF-S 18–55mm f/3.5–5.6 lens. If you purchased an EOS 5D Mk III or EOS 6D (full-frame sensor cameras), instead, you had the option of purchasing a kit version of the camera that included in the price an EF 24–105mm f/4L IS. Some retailers put together full-frame kits, including the EF 24–70mm f/2.8L in lieu of the EF 24–105mm f/4L IS. All lenses are excellent standard zooms and are intended to be photographers’ go-to lenses for much of their work (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 The EF 24–70mm f/2.8L (left) and the EF-S 18–55mm f/3.5–5.6 IS (right) are two popular Canon standard zoom lenses.

For the most part, any time you purchase a kit, the lens fits somewhere in this standard zoom range. Most folks consider standard focal lengths to be ranging from 24mm to 105mm on a full-frame sensor camera (dictated by design as opposed to a strict regulation), hence the popularity of the EF 24–105mm f/4L IS for the full-frame kit mentioned above. For the purposes of this chapter, we’ll go with these focal lengths as well when discussing standard lenses.

Range and Flexibility

The obvious advantage of a standard zoom—as well as a few standard primes if you choose to go that route—is its versatility. Rightly so, a standard zoom lens is built for the amount of flex a photographer demands of any one lens. I can’t think of another lens that sees a variety of focal lengths actually used when shooting. As I mentioned in the previous chapter, wide-angle zooms are typically used at their widest focal length, and the opposite happens for many telephoto-zoom lenses. However, the 40-some-odd millimeters of focal length many standard zoom lenses offer (some more) tend to get used.

The standard zoom lens creeps into the wide world, especially if the lens reaches as wide as 24mm or its EF-S equivalent (18mm on an EF-S lens is comparable to a 29mm full-frame perspective). At the same time, many reach 70mm or more, which is medium-telephoto territory. Not too shabby for one lens. For photographers on a budget or wanting to carry a minimum amount of gear, the standard zoom lens is ideal. It is the foundation for the lens trinity highlighted in Chapter 1, and it is the one I recommend that all novice photographers obtain first. Standard zooms run the gamut in terms of build quality and lens speed and features.

An additional advantage of the standard zoom lens is its coverage of landmark focal lengths, including 35mm and 50mm. Both focal lengths are valuable to many photographers, particularly those interested in photojournalism. We’ll spend more time discussing the 50mm lenses later in this chapter. However, it is important to mention—especially for those new to selecting gear for rental or purchase—that a standard zoom lens also allows the photographer to learn if she leans toward these two focal lengths and whether or not it is advantageous for her to purchase dedicated 35mm and/or 50mm prime lenses.

Real-Life Applications

Aside from the mechanical flexibility of standard lenses, especially standard zooms, they are also useful for a diverse range of photographic subject matter. More than anything else, this is the reason to own either a standard zoom or a couple of standard prime lenses, like a 35mm and a 50mm.

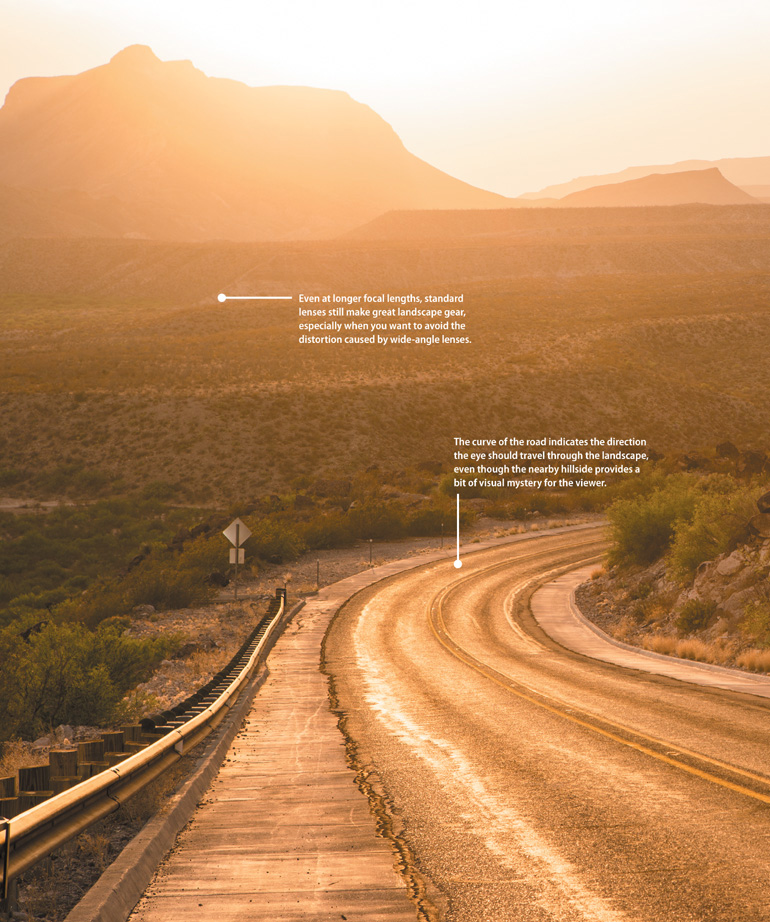

Landscape photography

Consider the flexibility of focal lengths the standard category includes, and then consider what you can adequately shoot with this range. I used to think that all of my landscape shots had to be made with an ultra-wide lens. Nowadays, I probably use 24mm as the widest focal length more than I do 17mm or wider (Figure 4.2). Why? It doesn’t distort as much as 17mm, it’s wide enough to showcase a lot of environment but tight enough to mitigate large void spaces in the sky or foreground, and probably most convenient, it is the widest extreme on a zoom lens that lets me quickly move from fairly wide to long with the twist of my wrist. This is useful for shooting in a river environment (Figure 4.3), where a wide perspective will provide one shot, and a tighter perspective will offer another in literally seconds (Figure 4.4).

ISO 100 • 1/6 sec. • f/22 • 24mm

Figure 4.2 At 24mm, a standard zoom lens is very capable of helping to create expansive landscape shots.

ISO 100 • 1/125 sec. • f/8 • 24mm

Figure 4.3 A standard zoom lens like the EF 24–105mm f/4L IS offers up great wide views of desert riparian landscapes.

ISO 100 • 1/125 sec. • f/11 • 105mm

Figure 4.4 At the same time, the long end of an EF 24–105mm f/4L IS helps compress the layers of the same landscape, making for a rather different image.

Photojournalism

The standard lens range is also very popular in the photojournalism and documentary fields of photography (Figure 4.5). It not only allows the photographer to work closely with his subject matter, but it also forces him to produce more intimate images based on physical proximity of the camera to the subject(s) (Figure 4.6). Some of the most compelling images ever made were created with a 35mm or 50mm lens. Technological limitations and availability prevented photographers in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s from obtaining longer lenses, which would have provided a different perspective. Yet the 35mm and 50mm lenses offered these photographers a great way to tell stories from a close yet observable distance. Because of this, the standard focal length range has remained popular for photography since photo essays were first popularized.

ISO 200 • 1/4000 sec. • f/2.2 • 50mm

Figure 4.5 A 50mm lens is nice to take on a photo walk, perfect for finding candid moments, like this family walking home in Carmona, Spain.

ISO 400 • 1/60 sec. • f/4 • 24mm

Figure 4.6 Standard lenses keep the distance between the subject and the photographer close and engaging, helping to create a feeling of actually being there for the viewer.

Portraiture

Standard focal lengths are also valuable for portraits. I know many environmental portrait photographers who consider their standard zooms the most important lenses in their bags. Whether you are shooting full-length portraits with the wider side of the lens (Figure 4.7) or head shots with the longer end (Figure 4.8), the standard zoom is as flexible for portraits as it is for landscapes. Keep in mind that the wider focal lengths exhibit higher levels of distortion and keystoning, which might prove disadvantageous for fashion work. Subsequently, many waist-up, or medium, portraits are made at the longer focal lengths in the standard range (Figure 4.9), including perhaps the most popular portrait focal length Canon makes, the 85mm (which we will touch on shortly).

ISO 100 • 1/125 sec. • f/2.8 • 50mm

Figure 4.7 A standard lens is my favorite lens for making full-length portraits.

ISO 200 • 1/160 sec. • f/8 • 70mm

Figure 4.8 The long end of a standard zoom lens is the preferred focal length I use for studio work, as illustrated in this portrait of angler Byron Kennedy.

ISO 200 • 1/160 sec. • f/8 • 70mm

Figure 4.9 Angler Lindsay West Kennedy poses for an in-studio shot made at 70mm, a great focal length for a variety of portrait work.

Sports and wildlife photography

We can’t leave out the sports and wildlife folks here. Although the majority of sports and wildlife work is achieved using telephotos and super-telephoto lenses, I don’t know a single photographer interested in these areas who does not own a standard zoom lens or at least one lens that fits within the standard focal length range. Take American football photography, for example. When the action on the field gets closer and closer to the end zone, there is only so much a 400mm lens will offer you. A standard zoom, like the EF 24–70mm f/2.8 L, keeps the photographer prepared for a play that moves closer to her side of the field, but it is even more useful for those milder activities like halftime (Figure 4.10).

ISO 800 • 1/1250 sec. • f/2.8 • 24mm

Figure 4.10 A standard zoom lens is nice to have on the football field, especially for capturing the halftime show, where being close to the action doesn’t mean getting knocked down.

Other sports that allow spectators a close look at the action, such as cycling, are great activities to shoot with both wide-angle and medium-telephoto perspectives (Figure 4.11). As so many photographers have stated over the years, being closer to the action makes for more interesting images, and a standard zoom lens or a few prime equivalents allow you to do just that.

ISO 100 • 1/20 sec. • f/5 • 50mm

Figure 4.11 You can make a pan of a cyclist easily with a standard lens from the side of the road.

Wildlife photography may offer a few more challenges than sports do, even at the longer end of the standard range of focal lengths, but certain subjects allow the shooter to use shorter lenses (Figure 4.12). Shorter focal lengths are also easier to use in conjunction with remote cameras set up to shoot wildlife from hidden areas.

ISO 100 • 1/200 sec. • f/9 • 73mm

Figure 4.12 Wildlife can be tough with a standard zoom lens, but with enough patience, you can make a comical shot of the smallest animals.

And, although I have never had the pleasure of testing this myself, I hear a standard zoom is ideal for underwater photography.

Composing With Standard Zooms and Primes

Composing with the standard range of focal lengths isn’t necessarily different from composing with any lens. Finding and using strong lines, following the rule of thirds, and the like, are standard compositional techniques. However, trying to envision those things coming together with so many useful focal lengths can be daunting, especially while on location, when everything is coming at you at once, or when you want to maximize the most from your photography in a short amount of time.

Points of Interest

Envisioning shots with wide-angle lenses is relatively easy. I’m not saying wide-angles are easy to use successfully, but the wide-angle look is very familiar. Therefore, seeing in a wide perspective, where compositional interests such as lines are strongly emphasized, isn’t as intimidating as seeing with other perspectives. It’s more work envisioning images with the standard range of lenses. I am a fan of simplifying, though, and that’s what I want to encourage in your own use of standard focal lengths.

Primary, secondary, and tertiary

Using all (or some) of those components of great composition covered in the previous chapter, focus on finding and providing a way for viewers to notice significant points of interest in your shots. You can use these points to guide the eye through the shot, from one direction to the other (Figure 4.13), or use them to isolate strong subjects over minor ones or a complementary background (Figure 4.14). Also consider being able to showcase multiple points of interest as if there were a visual hierarchy to how they should be physically viewed. A primary interest point—one that is the most important to the shot—may be placed in the foreground, a secondary interest point behind it (staggered to an opposite side perhaps), and a tertiary point placed as the least significant of the three (Figure 4.15). You may choose to have only one real point of interest in the frame, or as many as you can keep organized for the human eye.

ISO 400 • 1/40 sec. • f/8 • 24mm

Figure 4.13 The flowers in the foreground serve as a primary point of interest, which lead the eye to a secondary point—the lines of the fence—and on to the abandoned cattle station, the tertiary interest point.

ISO 320 • 1/30 sec. • f/4 • 82mm

Figure 4.14 Artist Charice Adams in front of some of her work in a local gallery. Using points of interest for composition can be as simple as one subject placed in front of the other.

ISO 400 • 1/60 sec. • f/3.5 • 24mm

Figure 4.15 With football coach Kliff Kingsbury serving as the primary point of interest, a wide-angle portrait includes the helmets as secondary interest points, and the image of the fans on the wall as a tertiary point.

Using this points-of-interest technique is by no means relegated to standard focal lengths only. I encourage everyone to use it at any focal length. However, it is a great way to simplify working with lenses and a range of focal lengths that cross the wide-to-telephoto divide. Although this divide is not over 100mm, it is incredible the visual difference one extreme has to the other (Figures 4.16 and 4.17).

ISO 200 • 1/8 sec. • f/22 • 35mm

Figure 4.16 At 35mm, you can see a line among diminished points of interest.

ISO 200 • 1/4 sec. • f/22 • 70mm

Figure 4.17 Yet, at 70mm, the hills in the background compress more with the foreground elements, new lines are formed, and interest points are more strongly exhibited.

No matter how much you zoom in (or out) on your subject matter, create a visual roadmap the viewer can follow from one strong point of interest to the other. Sometimes this requires looking through the lens at various focal lengths before snapping the shot.

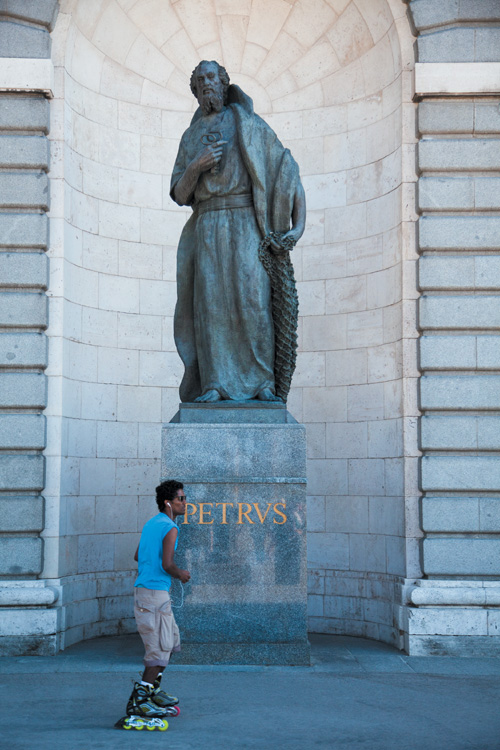

Storytelling with lenses

An added benefit of shooting points of visual interest is the storytelling that results. In any given environment, a point of interest serves as a component of the visual story that exists in an image (or multiple images). When these points of interest are tied together, a visual narrative is created based on our own ability to comprehend their connection (Figure 4.18).

ISO 200 • 1/500 sec. • f/4 • 55mm

Figure 4.18 A skater riding past a statue of Saint Peter in Madrid conveys a modern society set against the backdrop of tradition.

Photography can be rather interpretive, and there’s a sliding scale as to how much interpretation is required when creating and viewing an image (Figure 4.19). As image makers, though, we are at the visual helm of creating meaning with our images.

ISO 200 • 1/500 sec. • f/11 • 90mm

Figure 4.19 The gloomy look of the Rio Grande and the U.S./Mexican border in far West Texas sets up an image for quite a bit of interpretive value.

Fortunately, standard focal lengths have always been right alongside this storytelling process. Since the look of these types of lenses isn’t as visually defined as, say, a 14mm or a 500mm, a photographer’s attention to composition is even more key to an image’s success. Combine that with points of interest that increase a viewer’s understanding of a context or engage a viewer in a more active way (Figure 4.20), and the lens helps the photographer do what he set out to do.

ISO 100 • 1/1600 sec. • f/2.8 • 24mm

Figure 4.20 Pushing in tight on the secondary interest point—the West Texas grassland—helps highlight the primary subject of interest, a staff member of the Texas Parks and Wildlife department.

Framing

Although not unique to the standard range of focal lengths, one key compositional technique I find myself using quite a bit when I have a standard zoom lens in hand is framing. Framing, the use of content within an image to drive attention toward the subject, is a great technique to employ when you cannot rely largely on a perspective effect of a lens (Figure 4.21). An overhanging tree or the architecture of a building can visually frame up the subject of a portrait (Figure 4.22) or activity of interest.

ISO 50 • 1/1000 sec. • f/4 • 50mm

Figure 4.21 The shadowed trees and foreground frame the Cervantes Monument in Madrid, Spain.

ISO 100 • 1/320 sec. • f/2 • 50mm

Figure 4.22 I used an out-of-focus square column on the left to force the eye to the right and toward doctoral graduate Patrick Merle.

I often find myself using arches and walls as framing devices, where shooting at 35mm or longer allows me to keep most of the straight lines of an environment in perspective. Just about anything can serve as a frame, and sometimes all it takes to find frames is putting your eye to the viewfinder. Again, when you are not using a lens effect—e.g., wide-angle lens—to draw the eye to what is important in the frame, you’ll want to take advantage of framing devices while also employing other compositional techniques with a standard lens (Figure 4.23).

ISO 100 • 1/800 sec. • f/2 • 50mm

Figure 4.23 Using foreground material to frame up a shot of mother and daughter—who are placed along the right-third line of the frame—creates an appealing way to direct the viewer to the right side of the frame.

Over the Shoulder

Speaking of framing, one technique that’s useful with the longer extremes of standard focal lengths is what we’ll call the over-the-shoulder shot. These are popular shots of people using out-of-focus foreground material—many times they are the shoulders of other people talking to the subject—to push attention toward the person being photographed. Think corporate public-relations shots of employees enjoying their jobs (Figure 4.24). As cheesy as that example sounds, this technique forces the eye to look directly at the most important part of the frame without sacrificing environmental details, such as the person connected to the shoulder being used to frame the primary subject (Figure 4.25).

ISO 1600 • 1/60 sec. • f/2.8 • 40mm

Figure 4.24 Over-the-shoulder shots made at longer standard focal lengths are a great way to make viewers feel as if they are with the primary subject of interest.

ISO 800 • 1/200 sec. • f/2 • 50mm

Figure 4.25 Getting the camera low and behind the children gives the viewer a childlike perspective while encountering Santa Claus.

Of course, this type of composition is not limited to human subject matter. Nor does it have to involve a shoulder. The idea here is to draw attention to important subject matter by reducing the focus of the foreground and background (open up those apertures), de-cluttering the shot by moving in tight, and isolating the subject through simplifying the composition (Figure 4.26). I recommend using longer focal lengths, such as 70mm to 105mm, for these types of shots because of the increased compression. Using wider focal lengths may enlarge the size of the foreground—the lesser important subject—and create an expansive distance between it and the primary subject.

ISO 200 • 1/80 sec. • f/5.6 • 32mm

Figure 4.26 Trees surrounding the royal palace in Madrid serve as a great “shoulder,” or framing device, for the magnificent building.

50mm: Normal Perspective

If you were going to get only one prime lens in the standard category, I would have a hard time recommending any lens other than the 50mm. After all, it is the standard around which the standard range of focal lengths is based (Figure 4.27). The 50mm is widely known as the focal length that provides a perspective most similar to human perspective. It lacks the peripheral vision we have, but in terms of the relationship between all of the content we see—their sizes and distances from each other—50mm gets pretty close (Figure 4.28). Hence the moniker normal perspective.

ISO 200 • 1/125 sec. • f/8 • 50mm

Figure 4.28 On a full-frame camera, 50mm maintains our own eyes’ perspective of our surroundings, minus our peripheral vision. You get the same perspective with a 31mm lens on an APS-C crop sensor.

Also known as normal lenses, 50mm lenses have been around a while, and they’re not going anywhere. I would dare say they are some of the most popular lenses available to photographers. They were the kit lenses of choice decades ago. Since they relate so well to our own eyes, 50mm lenses are extremely popular with photojournalists and documentary photographers because of their straightforward, non-manipulative perspective, their relatively small size, and their simplicity (Figure 4.29).

ISO 200 • 1/200 sec. • f/2 • 50mm

Figure 4.29 At 50mm, the shot can be pushed in fairly tight on carpenter Sly Luna without distorting his form or the form of other structures around him.

Like most prime lenses, 50mm lenses are also popular in part due to their extremely fast apertures. Canon offers three 50mm lenses (EF 50mm f/1.8, EF 50mm f/1.4, and EF 50mm f/1.2L) that differ on, among other features, maximum aperture openings. All other features aside, each of Canon’s 50mm lenses has an extremely fast aperture (Figure 4.30). Achieving fast shutter speeds in dimly lit environments is possible when you’re using apertures that open this wide (Figure 4.31).

ISO 100 • 1/3200 sec. • f/1.2 • 50mm

Figure 4.30 Achieve extremely low depth of field easily with any of Canon’s three 50mm lenses.

ISO 400 • 1/640 sec. • f/2 • 50mm

Figure 4.31 The fast apertures of most prime glass, especially Canon’s 50mm lenses, help in creating images in dimly lit environments, such as this jeweler’s desk.

These large apertures also provide extremely shallow depth of field. Soft, creamy, out-of-focus areas are unique to apertures larger than f/2.8, and given the right distance from the subject, the 50mm lens has a look all its own (Figure 4.32). When zoomed in to capture medium waist-up shots of people in action and street photography, a 50mm lens offers superior isolation value. The depth of field is so shallow that the primary subject in focus sometimes looks as though it was digitally composited into the frame later.

ISO 100 • 1/200 sec. • f/2 • 50mm

Figure 4.32 A soft bokeh keeps the visual attention on the couple while providing a signature 50mm lens look to the entire frame.

85mm: Standard Portrait Lens

Want to cause lens envy? Roll into a photography party (do they have those?) with an EF 85mm f/1.2L on your camera. Heck, even the lesser expensive—but sharp as a tack—EF 85mm f/1.8 will have people looking (Figure 4.33). The first thing people will think: portrait shooter (regardless of whether or not that’s how you would describe your work).

Figure 4.33 The EF 85mm f/1.8, one of two Canon 85mm lenses, is my favorite based on focusing speed, sharpness, and price.

Why It’s Great

In terms of it being the perfect portrait lens, the 85mm focal length has several things going for it. First, in any iteration, it is an extremely fast lens. Like the 50mm trio from Canon, both 85mm lenses sport wide opening apertures and an incredibly shallow depth of field. Popular among environmental portrait photographers, wedding shooters, children photographers, and folks producing great Hollywood head shots, both 85mm lenses offer superb bokeh (Figure 4.34). When pushed in tight to the subject and left wide open, the lens makes just about everything out of focus except for the focal point on a subject’s face (Figure 4.35). Distracting backgrounds are manipulated into abstract blobs of color and light with these lenses, perfect for cleanly isolating your subject in the frame.

ISO 200 • 1/160 sec. • f/1.8 • 85mm

Figure 4.34 Great for tight portraits, the Canon 85mm lenses are made for taking advantage of light as well as interesting backgrounds.

ISO 200 • 1/500 sec. • f/1.8 • 85mm

Figure 4.35 Backgrounds fade easily into beautiful, blurred color and light when either of the Canon 85mm lenses is pushed close to its minimum focusing distance from the subject.

The second feature of this great-for-portraiture focal length is that it is long enough to create a bit of foreground-to-background compression, but it is still short enough that the photographer can stay relatively close to her subject. The compression caused by the lens is nice because it helps simplify shots, particularly when combined with very shallow depth of field (Figure 4.36). Keep an eye out for sharp, clean backgrounds. The proximity of the shooter to the subject is nice because it enables a tight relationship between the two. They can have conversations easily. The photographer can give instructions without yelling and can simply make the experience comfortable for the subject, who may feel removed from the action if the shooter is farther away than an 85mm focal length will allow for a head shot or other tighter portraits.

ISO 100 • 1/400 sec. • f/2.8 • 85mm

Figure 4.36 There is just enough compression at 85mm to keep the background close to the subject, but not so much that it becomes decontextualizing should you choose not to use a wide-open aperture.

The Cost of Owning an 85mm

Like the Canon lineup of 50mm lenses, the two 85mm lenses differ on a few features and price points. The EF 85mm f/1.8 is a more affordable iteration of the lens, featuring an all-plastic lens barrel (although it comes with a metal mount), and of course, a smaller maximum aperture. Many believe—including yours truly—that the f/1.8 version of the lens focuses faster than the f/1.2L. (The L-series version features an electronic focus requiring electricity from the camera to operate as opposed to a mechanical focus like most EF and EF-S lenses—ultimately, it makes it a slower-focusing lens.) In my opinion, this is a big issue, especially when the f/1.8 version is tack sharp. However, for those shooting mostly posed portraits, the slower focusing speed of the more-expensive f/1.2L may not be such a downside. The difference in price? There is a difference in price between the lenses of over US$1,500. But, with that price comes a very stout and heavy metal barrel, excellent glass, and the admiration of all of your photo buddies (well, maybe...).

Although I was willing to splurge on the L-series 50mm, my own style of shooting doesn’t justify the expense of the EF 85mm f/1.2L. Instead, I opted to purchase the more affordable EF 85mm f/1.8. Both are excellent pieces of glass, and a choice between the two—like with all lenses—is based on personal preference.

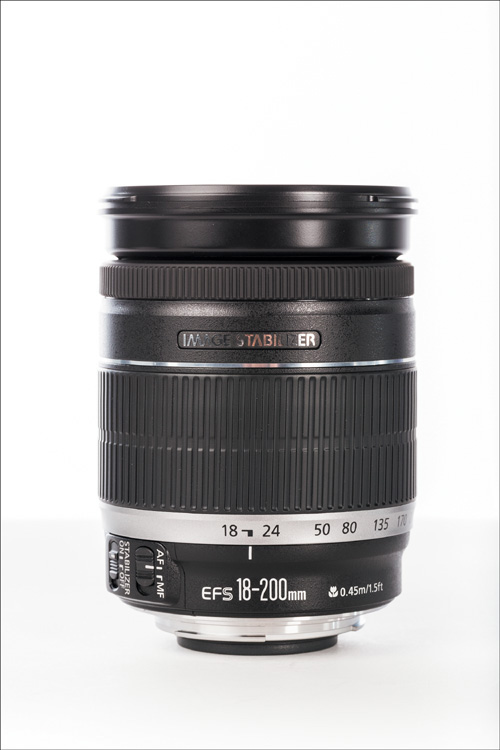

The All-Around Lens

Every year I teach a 15-day editorial field course to 14 students at the university. At least one student will ask me if I can recommend one lens that will work for the large majority of photography we produce in the class (but won’t break the bank). Having had a few meals on the cheap while I was in college, I sympathize with their wanting to save money. Luckily, I’m quick to recommend the EF-S 18–200mm f/3.5–5.6 IS (Figure 4.38).

Figure 4.38 For Canon APS-C crop-sensor-camera users, the EF-S 18–200mm f/3.5–5.6 IS is the perfect lens—focal length flexibility at a great value.

The 18–200mm focal length range is, for one thing, incredibly long. Not only is it long, though, it offers the photographer some of the most useful focal lengths he will need and use, all in one lens. A fairly wide perspective all the way to reaching telephoto perspective lets the photographer make the most of many different environments and types of photography. It truly is an all-around lens. To be honest, I have always been skeptical of lenses that try to cover this much ground in a zoomable package. For example, I’ve always been wary of the EF 100–400mm f/4.5–5.6L IS because lens sharpness tends to suffer when extremely long ranges are incorporated into zoom lenses like this. However, the EF-S 18–200mm f/3.5–5.6 IS has not given me cause to shudder, especially at a price point well below US$1,000.

Another nice thing about a lens like the EF-S 18–200mm f/3.5–5.6 IS is that it doesn’t have to be removed from the camera body much, if at all. This comes in handy when you might need to change lenses in poor weather (think rain or a dust storm) that may pose great risk to your camera body.

There is one catch. The lens highlighted here is an EF-S lens, only available for photographers using crop-sensor cameras, like any in the Rebel series. For those using full-frame cameras that only accept EF mount lenses, such a long range of coverage does not exist in a zoom lens—at least one that covers much of the standard focal range discussed in this chapter. However, there are several lenses that do include a great range, such as the EF 24–105mm f/4L IS and the EF 28–135mm f/3.5–5.6 IS. Of course, there is also the EF 28–300mm f/3.5–5.6L IS, but at more than US$1,000 more than the EF 24–105mm f/4L IS, it is cost prohibitive for a lot of folks. All, however, are nice EF alternatives to the popular EF-S 18–200mm f/3.5–5.6 IS.

Chapter 4 Assignments

Here are a few aesthetic and technical workouts that will help you improve your vision with, and operation of, the many lenses in the standard 24mm to 105mm range.

Working up interest

Let’s flex some serious composition muscles. Find a location that is important to the surrounding area. It could be something cultural like a fountain statue or museum, or something playful like a piece of playground equipment or outdoor basketball court. When you are on location, search for different ways to compose shots of it. Start dissecting the different kinds of subject matter that make up the location. Determine what is the most important. Consider that a primary interest point to which you want to direct the eye or use as an initial leading device to other areas of the location. After identifying the primary subject, find secondary and even tertiary points of interest to build into your composition. Again, use them to either lead the eye to the primary interest point, or use them to compositionally complement a dominating foreground interest point. Make several shots using different points along different lines, and think about foreground, midground, and background. To make it even more interesting, add a person (or people) to the mix.

Just be normal

On your next photo outing, shoot only at 50mm. That’s it. For those of you using an APS-C crop-sensor camera like a Rebel, 60D, or 7D, you’ll need to shoot at 31mm (or close). Get a feel for only shooting at this focal length and from this perspective. We often go really wide or really long, and we need practice seeing and shooting at normal perspective. Assess the size and distance between all of the components of the subject matter, gauge the distances you need to be from subjects for certain types of shots, and as always, work the frame’s composition!

Shoot shallow

While you are out on that photo walk, spend some time shooting with the aperture wide open. This works best if you have a 35mm, 50mm, or 85mm prime lens. Set the lens to its maximum aperture, and work at varying distances on one subject to nail focus. If possible, use a human subject and focus on her eyes. Once you do so, re-compose for the shot, and see how far your focus drifted (if at all) away from the eye. Did the focal plane move forward or backward? Determine how you might best be able to overcome this disadvantage of the extremely wide aperture settings inherent in many primes. Move to manual focus to see if you can eyeball it any better. Work on this technique continually to ensure you do not come away with out-of-focus shots.

Share your results with the book’s Flickr group!

Join the group here: www.flickr.com/groups/canonlenses_fromsnapshotstogreatshots