Chapter 5

Understanding Different Threat Actors, Vectors, and Intelligence Sources

This chapter covers the following topics related to Objective 1.5 (Explain different threat actors, vectors, and intelligence sources) of the CompTIA Security+ SY0-601 certification exam:

Actors and threats

Advanced persistent threat (APT)

Insider threats

State actors

Hacktivists

Script kiddies

Criminal syndicates

Hackers

Authorized

Unauthorized

Semi-authorized

Shadow IT

Competitors

Attributes of actors

Internal/external

Level of sophistication/capability

Resources/funding

Intent/motivation

Vectors

Direct access

Wireless

Email

Supply chain

Social media

Removable media

Cloud

Threat intelligence sources

Open source intelligence (OSINT)

Closed/proprietary

Vulnerability databases

Public/private information sharing centers

Dark web

Indicators of compromise

Automated indicator sharing (AIS)

Structured threat information eXpression (STIX)/Trusted automated eXchange of indicator information (TAXII)

Predictive analysis

Threat maps

File/code repositories

Research sources

Vendor websites

Vulnerability feeds

Conferences

Academic journals

Request for comments (RFC)

Local industry groups

Social media

Threat feeds

Adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP)

This chapter covers the different types and attributes of threat actors. You also learn what threat intelligence is, what it is used for, and the different types of threat intelligence sources and formats. The chapter concludes with a list of research resources that individuals and organizations can use to understand today’s threats and to protect their networks and systems.

“Do I Know This Already?” Quiz

The “Do I Know This Already?” quiz enables you to assess whether you should read this entire chapter thoroughly or jump to the “Chapter Review Activities” section. If you are in doubt about your answers to these questions or your own assessment of your knowledge of the topics, read the entire chapter. Table 5-1 lists the major headings in this chapter and their corresponding “Do I Know This Already?” quiz questions. You can find the answers in Appendix A, “Answers to the ‘Do I Know This Already?’ Quizzes and Review Questions.”

Table 5-1 “Do I Know This Already?” Section-to-Question Mapping

Foundation Topics Section |

Questions |

|---|---|

Actors and Threats |

1–2 |

Attributes of Actors |

3–4 |

Attack Vectors |

5–6 |

Threat Intelligence and Threat Intelligence Sources |

7–8 |

Research Sources |

9–10 |

Caution

The goal of self-assessment is to gauge your mastery of the topics in this chapter. If you do not know the answer to a question or are only partially sure of the answer, you should mark that question as wrong for purposes of the self-assessment. Giving yourself credit for an answer you correctly guess skews your self-assessment results and might provide you with a false sense of security.

1. Which of the following threat actors typically aims to cause denial-of-service conditions or deface websites due to a political or social belief?

Hacktivists

Semi-authorized hackers

Script kiddies

Nation state actors

2. Which of the following threat actors is typically motivated by money? (Choose the best answer.)

Authorized hackers

Criminal syndicates and organized crime

Exploit groups

None of these answers are correct.

3. Which of the following attributes make threat actors different?

Level of sophistication

Resources

Funding

All of these answers are correct.

4. Which incident response concept is designed to represent a cybersecurity incident and is made up of four parts?

FIRST

InfraGard

Diamond Model of Intrusion

All of these answers are correct.

5. Which of the following is an effective attack vector where an attacker could modify or tamper hardware or software from a vendor to perform mass compromise attacks?

Supply chain

Removable media

Wireless

Direct access

6. Which of the following elements could an attacker leverage to perform a cloud-based attack?

Misconfigured VMs

Unpatched applications and operating systems

Misconfigured storage buckets

All of these answers are correct.

7. Which term refers to the knowledge about an existing or emerging threat to assets, including networks and systems?

Threat intelligence

Threat feed

Threat model

None of these answers are correct.

8. Which technique is used when you leverage public information from DNS records, social media sites, websites, search engines, and other sources for reconnaissance?

OSINT

Threat maps

Threat models

Threat analysis

9. Which of the following could be threat and vulnerability research sources?

Vendor websites

Threat feeds

Vulnerability feeds

All of these answers are correct.

10. Which framework was created by MITRE to describe adversary tactics and techniques?

InfraGard

CVE

ATT&CK

CWE

Foundation Topics

Actors and Threats

It’s important to understand the types of attackers that you might encounter and their characteristics and personality traits. Keep in mind that these “actors” can find ways to access systems and networks just by searching the Internet. Some attacks can be perpetrated by people with little knowledge of computers and technology. However, other actors have increased knowledge, and with knowledge comes power—the type of power you want to be ready for in advance. However, all levels of attackers can be dangerous. Let’s look at several of the actors now.

The first of these personas is the script kiddie. This unsophisticated individual has little or no skills when it comes to technology. This person uses code that was written by others and is freely accessible on the Internet. For example, a script kiddie might copy a malicious PHP script directly from one website to another; only the knowledge of “copy and paste” is required. This derogatory term is often associated with juveniles. Though the processes they use are simple, script kiddies can knowingly (and even unwittingly) inflict incredible amounts of damage to insecure systems. These people almost never have internal knowledge of a system and typically have a limited amount of resources, so the amount, sophistication, and extent of their attacks are constrained. They are often thrill-seekers and are motivated by a need to increase their reputation in the script kiddie world.

Next is the hacktivist—a combination of the terms hack and activist. As with the term hacker, the name hacktivist is often applied to different kinds of activities—from hacking for social change, to hacking to promote political agendas, to full-blown cyberterrorism. Due to the ambiguity of the term, a hacktivist could be inside a company or attack from the outside and will have varying amounts of resources and funding. However, the hacktivist is usually far more competent than a script kiddie.

Cybercriminals might work on their own, or they might be part of criminal syndicates and organized crime—a centralized enterprise run by people motivated mainly by money. Individuals who are part of an organized crime group are often well funded and can have a high level of sophistication.

Individuals might also carry out cyber attacks for governments and nation states. In this case, a government—and its processes—is known as an advanced persistent threat (APT), though this term can also refer to the set of computer-attacking processes themselves. Often, an APT entity has the highest level of resources, including open-source intelligence (OSINT) and covert sources of intelligence. This, coupled with extreme motivation, makes the APT one of the most dangerous foes. In many cases, APTs are tied to nation state actors. It is not a taboo anymore that governments also use cyber techniques as a method of warfare. State actors can use adversarial techniques to steal intellectual property, cause disruption, and potentially compromise critical infrastructure.

Note

OSINT is covered in more detail later in this chapter.

Companies should be prepared for insiders and competitors as well. In fact, they might be one and the same. An insider threat can be one of the deadliest to servers and networks, especially if the person making this threat is a system administrator or has security clearance at the organization. Not all “insiders” may be malicious, however. Think about the risks that shadow IT may introduce in a company. In shadow IT an employee or a group of employees use IT systems, network devices, software, applications, and services without the approval of the corporate IT department. For example, an engineer may just deploy a physical or virtual server and host his or her own application in it. The engineer may not patch or monitor that system often for any security vulnerabilities. Consequently, threat actors may easily compromise the vulnerable system or application. This problem has grown exponentially in recent years because more companies and individuals are adopting cloud-based applications and services. It is very easy to “spin off” a new virtual machine (VM), container, or storage element in the cloud. Employees often put sensitive corporate information in cloud services that are often not closely monitored, introducing a significant risk to the corporation.

You should know these actors and their motivations, but in the end, it doesn’t matter too much what you call the attackers. Be ready to prevent the basic attacks and the advanced attacks and treat them all with respect.

Not all hackers are malicious, however. That’s right! There are different types of hackers. Different organizations use various names, but some of the common labels include the following:

An authorized hacker (white hat) is also known an ethical hacker; this term describes those who use their powers for good. They are often granted permission to hack.

An unauthorized hacker (black hat) is a malicious hacker who may have a wide range of skill, but this category is used to describe those hackers involved with criminal activities or malicious intent.

A semi-authorized (gray hat) hacker falls somewhere in the middle of authorized and unauthorized. This person doesn’t typically have malicious intent but often runs afoul of ethical standards and principles.

Attributes of Threat Actors

Now that you have learned about the different types of threat actors, let’s try to understand their attributes, intent, and motivation. The intent and motivation, in most cases, differ depending on the type of attacker. For example, the motivation for hacktivists is typically around protesting against something that they do not agree with (a political or religious belief, human rights, etc.). Hacktivists tend to use disruption techniques, perform denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, or deface websites. The intent of criminals is typically to make money. Nation state actors can also have different motivations and intent. Some nation state actors just want to steal intellectual property from another nation, government, or a corporation; whereas others want to cause disruption and bring down critical infrastructure. Another example is an internal actor (insider) who in some cases could be motivated by money being offered from an external actor (either to steal information or to cause disruption). The internal actor could also be a disgruntled employee who may leave a backdoor either to later access confidential information or to trigger a denial-of-service condition on critical systems and applications.

Another difference between the different types of threat actors is the level of sophistication/capability and the resources/funding. Obviously, a disgruntled employee, a hacktivist, or an amateur script kiddie will not have the resources and funding that nation state actors may have at their disposal. Criminal organizations in some cases may have more resources, money, and access to sophisticated exploits than hacktivists.

Active intrusions start with an adversary who is targeting a victim. The adversary will use various capabilities along some form of infrastructure to launch an attack against the victim. Capabilities can be various forms of tools, techniques, and procedures, while the infrastructure is what connects the adversary and victim.

Attack Vectors

A threat actor may leverage different attack vectors:

Direct access: Direct network access or physical access to a device provides one type of attack vector.

Wireless: This attack vector includes hijacking wireless connections, rogue wireless devices, evil twins, and the attacks you learned in Chapter 4, “Analyzing Potential Indicators Associated with Network Attacks.”

Email: Email attack vectors include phishing and spear phishing emails with malicious attachments or malicious links.

Supply chain: One of the most effective attacks for mass compromise is to attack the supply chain of a vendor to tamper with hardware and/or software. This tampering might occur in-house or earlier, while in transit through the manufacturing supply chain.

Social media: This attack vector includes leveraging social media platforms for reconnaissance or to launch social engineering attacks.

Removable media: Many attackers have successfully compromised victim systems by just leaving USB sticks (sometimes referred to as USB keys or USB pen drives) unattended or placing them in strategic locations. Often users think that the devices are lost and insert them into their systems to figure out who to return the devices to; before they know it, they may be downloading and installing malware. Plugging in that USB stick you found lying on the street outside your office could lead to a security breach.

Cloud: Attackers can leverage misconfigured and insecure cloud deployments including unpatched applications, operating systems, and storage buckets.

Threat Intelligence and Threat Intelligence Sources

Threat intelligence refers to knowledge about an existing or emerging threat to assets, including networks and systems. Threat intelligence includes context, mechanisms, indicators of compromise (IoCs), implications, and actionable advice. This type of intelligence includes specifics on the tactics, techniques, and procedures of these adversaries. The primary purpose of threat intelligence is to inform business decisions regarding the risks and implications associated with threats.

Converting these definitions into common language could translate to threat intelligence being evidence-based knowledge of the capabilities of internal and external threat actors. This type of data can be beneficial for the security operations center (SOC) of any organization. Threat intelligence extends cybersecurity awareness beyond the internal network by consuming intelligence from other sources Internet-wide related to possible threats to you or your organization. For instance, you can learn about threats that have impacted different external organizations. Subsequently, you can proactively prepare rather than react after the threat is seen against your network. One service that threat intelligence platforms typically provide is an enrichment data feed.

During the investigation and resolution of a security incident, you may also need to communicate with outside parties regarding the incident. Examples include but are not limited to contacting law enforcement, fielding media inquiries, seeking external expertise, and working with Internet service providers (ISPs), the vendor of your hardware and software products, threat intelligence vendor feeds, coordination centers, and members of other incident response teams.

You can also share relevant incident IoC information and other threat intelligence with industry peers. There are public and private information sharing centers. A good example of information-sharing communities includes the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC).

Tip

Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) are private-sector critical infrastructure organizations and government institutions that collaborate and share information between each other. ISACs exist for different industry sectors. Examples include automotive, aviation, communications, IT, natural gas, elections, electricity, financial services, health-care, and many other ISACs. You can learn more about ISACs at www.nationalisacs.org.

A cybersecurity incident response plan should account for these types of interactions with outside entities. It should also include information about how to interact with your organization’s public relations department, legal department, and upper management. You should also get their buy-in when sharing information with outside parties to minimize the risk of information leakage. In other words, you should avoid leaking sensitive information regarding security incidents with unauthorized parties. These actions could potentially lead to additional disruption and financial loss. You should also maintain a list of all the contacts at those external entities, including a detailed list of all external communications for liability and evidentiary purposes.

You can also subscribe to commercial and open-source threat intelligence feeds. Some of these feeds could be closed or proprietary. In cybersecurity, there is a concept called open-source intelligence (OSINT). OSINT applies to offensive security (ethical hacking/penetration testing) and defensive security. In offensive security, OSINT enables you to leverage public information from DNS records, social media sites, websites, search engines, and other sources for reconnaissance—in other words, to obtain information about a targeted individual or an organization. When it comes to threat intelligence, OSINT refers to public and free sources of threat intelligence.

Tip

The following GitHub repository includes numerous references about OSINT tools and sources: https://github.com/The-Art-of-Hacking/h4cker/tree/master/osint.

You also could leverage other sources to obtain information about threats, including the dark web. The “deep web” is the part of the Internet that has not been indexed by search engines like Google or Bing. The dark web is just a subset of what is considered the “deep web” and is the place where many threat actors perform malicious activities such as selling stolen credit card numbers, health records, and other personal information. Criminals also sell drugs, guns, counterfeit equipment, and exploits. In some cases, security professionals go to the dark web to perform research and try to find different threats and exploits that could affect their organization. This task is easier said than done. This is why several companies sell “dark web monitoring” and threat intelligence services.

As a security professional, you also have to pay attention to vulnerability databases and feeds. One of the most popular vulnerability databases is the United States National Vulnerability Database (NVD), part of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). You can access the NVD at https://nvd.nist.gov.

The NVD provides information about vulnerabilities disclosed worldwide and is assigned the Common Vulnerability and Exposure (CVE) identifiers. CVE is a standard created by MITRE (www.mitre.org) that provides a mechanism to assign an identifier to vulnerabilities so that you can correlate the reports of those vulnerabilities among sites, tools, and feeds. You can obtain additional information about CVE at https://cve.mitre.org.

When it comes to threat intelligence, several standards and formats allow you to perform automated indicator sharing (AIS) within your organization or with industry peers. The next section covers the most popular standards and formats for threat intelligence exchange.

Structured Threat Information eXpression (STIX) and the Trusted Automated eXchange of Indicator Information (TAXII)

The Structured Threat Information eXpression (STIX) is an OASIS standard designed for sharing of cyber-attack information. STIX details can contain data such as the IP addresses or domain names of command-and-control servers (often referred to C2 or CnC), malware hashes, and so on. STIX was originally developed by MITRE and is now maintained by OASIS.

The Trusted Automated eXchange of Indicator Information (TAXII) is also an OASIS standard that provides an open transport mechanism that standardizes the automated exchange of cyber-threat information. TAXII was originally developed by MITRE and is now maintained by OASIS.

Note

You can access the STIX and TAXII specification details at https://oasis-open.github.io/cti-documentation.

In short, STIX is the actual threat intelligence document in JSON format and TAXII is the transport mechanism.

Example 5-1 provides a STIX threat intelligence document.

Example 5-1 A STIX Threat Intelligence Document

{

"type": "bundle",

"id": "bundle--aaaa-bbbb-cccc-1234-123123123",

"objects": [

{

"type": "indicator",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": " indicator-aaabbbcc-b0123-cbc ",

"created": "2020-10-21T11:09:08.123Z",

"modified": "2020-10-21T11:09:08.123Z",

"name": "Windows Trojan Trojan/Win32.PornoAsset.R39927",

"description": "This file hash indicates that a sample of Trojan/Win32.PornoAsset.R39927 is present.",

"indicator_types": [

"malicious-activity"

],

"pattern": "[file:hashes.'SHA-256' = '0f1f19244fcc11818083aa1f943bbead338f89e046b8a57a50ec7cf48b62496f']",

"pattern_type": "stix",

"valid_from": "2020-03-11T08:00:00Z"

},

{

"type": "malware",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": " malware--aaaa-bbb-cccc-dddd-eeee ",

"created": "2020-10-21T11:09:08.123Z",

"modified": "2020-10-21T11:09:08.123Z",

"name": "Poison Ivy",

"malware_types": [

"remote-access-trojan"

],

"is_family": false

},

{

"type": "relationship",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "relationship--12344-4334-1253-6644-b2455",

"created": "2020-10-21T11:09:08.123Z",

"modified": "2020-10-21T11:09:08.123Z",

"relationship_type": "indicates",

"source_ref": "indicator-aaabbbcc-b0123-cbc",

"target_ref": "malware--aaaa-bbb-cccc-dddd-eeee"

}

]

}

Predictive analysis and predictive analytics can help discover security threats in your network. Machine-learning-powered solutions have evolved during the last few years, providing benefits that extend beyond signature-based intrusion detection and prevention. Many organizations have to handle large volumes of data from multiple security devices and sources. This makes it almost impossible for individuals to keep up and analyze. As described in Chapter 2, “Analyzing Potential Indicators to Determine the Type of Attack,” machine learning (ML) provides a way to quickly analyze security logs and data to perform advanced calculations on it in near real time and help respond to security incidents.

Several organizations have created threat maps to try to visualize the types of attacks and threats in their network and across the Internet. A cyber-threat map (also known as an attack map) is a real-time map of security attacks happening at any given time. These maps are visualizations from data aggregated from many different sensors around the world. Threat maps help illustrate how prevalent cyber attacks are.

Another source of threat and security information is file and code repositories. Threat actors often release exploits and breached data to file repositories like https://pastebin.com and code repositories like GitLab and GitHub.

Research Sources

Threat and vulnerability research sources include vendor websites, threat feeds, and vulnerability feeds from different providers, including security advisories from different providers. For example, the following link leads to the list of security advisories in Palo Alto products: https://security.paloaltonetworks.com. Likewise, the following link leads to the security advisories from Cisco: https://www.cisco.com/go/psirt. Most mature vendors disclose vulnerabilities affecting their products and services in a transparent way. Several commercial vendors also sell subscriptions to threat and vulnerability feeds.

You can learn and research new threats and vulnerabilities at security conferences, in academic journals, and from local industry groups. Examples of local industry groups include InfraGard (a collaborative effort between the FBI and the private sector), OWASP community chapters, DEF CON groups, and other local groups. Even social media (like Twitter) can be a source of security threat information.

You can also obtain deep technical information about threats and protocol deficiencies in the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) request for comments (RFC) drafts and publications (www.ietf.org).

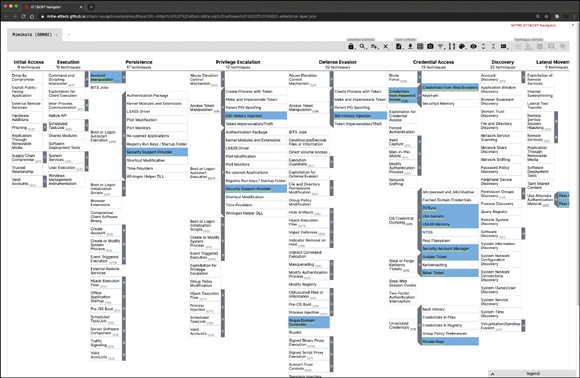

The MITRE ATT&CK Framework

Threat hunters assume that an attacker has already compromised the network. Consequently, they need to come up with a hypothesis of what is compromised and how an adversary could have performed the attack. For the threat hunting to be successful, hunters need to be aware of the adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that modern attackers use. This is why many organizations use MITRE’s ATT&CK framework to be able to learn about the tactics and techniques of adversaries. You will learn more about how MITRE’s ATT&CK can be used in threat hunting.

Threat hunting is not a new concept. Many organizations have performed threat hunting for a long time. However, in the last decade many organizations have recognized that they either have to implement a threat-hunting program or enhance their existing program to better defend their organization.

You can use the MITRE’s ATT&CK framework to learn about the tactics and techniques that attackers used during their campaigns. The information in ATT&CK can be extremely useful for threat hunting.

ATT&CK (https://attack.mitre.org) is a collection of different matrices of tactics and techniques. The ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise includes the tactics and techniques that adversaries use while preparing for an attack, including gathering of information (open-source intelligence, technical and people weakness identification, and more), and every single aspect of exploitation, post-exploitation, command and control, and other actions performed by the attacker. MITRE also provides a list of software (tools and malware) that adversaries use to carry out their attacks. You can access this list at https://attack.mitre.org/software.

You can also obtain detailed information about a specific tool or type of malware used by attackers for different purposes. For example, Figure 5-1 shows the well-known malicious memory-scraping and credential-dumping tool called Mimikatz in the MITRE ATT&CK Navigator.

FIGURE 5-1 The MITRE ATT&CK Navigator

As illustrated in Figure 5-1, the MITRE ATT&CK Navigator shows all the different tactics and techniques where Mimikatz has been used in many different attacks by a multitude of attackers.

Chapter Review Activities

Use the features in this section to study and review the topics in this chapter.

Review Key Topics

Review the most important topics in the chapter, noted with the Key Topic icon in the outer margin of the page. Table 5-2 lists a reference of these key topics and the page number on which each is found.

Table 5-2 Key Topics for Chapter 5

Key Topic Element |

Description |

Page Number |

|---|---|---|

Section |

Actors and Threats |

120 |

Paragraph |

Understanding the attributes, intent, and motivations of threat actors |

122 |

Section |

Attack Vectors |

122 |

Paragraph |

Understanding threat intelligence and indicators of compromise |

123 |

Section |

Structured Threat Information eXpression (STIX) and the Trusted Automated eXchange of Indicator Information (TAXII) |

125 |

Paragraph |

Understanding predictive analysis |

127 |

Paragraph |

Identifying threat and security information in file and code repositories |

127 |

Paragraph |

Surveying threat and vulnerability research sources such as vendor websites, threat feeds, and vulnerability feeds |

127 |

Section |

The MITRE ATT&CK Framework |

128 |

Define Key Terms

Define the following key terms from this chapter, and check your answers in the glossary:

advanced persistent threat (APT)

public information sharing centers

private information sharing centers

Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs)

open-source intelligence (OSINT)

automated indicator sharing (AIS)

Structured Threat Information eXpression (STIX)

Trusted Automated eXchange of Indicator Information (TAXII)

Review Questions

Answer the following review questions. Check your answers with the answer key in Appendix A.

1. What includes the tactics and techniques that adversaries use while preparing for an attack, including gathering of information (open-source intelligence, technical and people weakness identification, and more)?

2. What standard was designed to document threat intelligence in a machine-readable format?

3. What standard was designed as a transport mechanism of threat intelligence and to perform automated indicator sharing (AIS)?

4. What is the vulnerability database maintained by NIST?

5. What is the attack vector where evil twins are used?

6. You were hired to perform a penetration test against three different applications for a large enterprise. You are considered a(n) ______________ hacker.

7. You are hired to investigate a cyber attack. Your customer provided different types of information collected from compromised systems such as malware hashes and the IP address of a potential command and control (C2). What are these elements often called?

8. What name is often used to describe a government or state-sponsored persistent and sophisticated attack?

9. What is the term used when an employee or a group of employees use IT systems, network devices, software, applications, and services without the approval of the corporate IT department?