CHAPTER 13

Towards a New (Information) Architecture

We’ve spent the bulk of this book focused on establishing a methodology for organizing content: one based on meaning and purpose, on rules and relationships. We’ve explored practical approaches to making smart decisions about how to structure and store information. We’ve walked through examples of how others are creating more reusable, mobile-ready, flexible content.

And yet, this book isn’t really about method; it’s about mindset: about establishing a way of thinking that will serve your content—not to mention your users, your organization, and your sanity—well into the future. It’s about building a framework for thinking about content, not answering every question you’ll encounter about it.

After all, methods must adjust with time and technology, changing as new tools are built and new ideas developed. But a mindset that’s flexible, more focused on retaining content’s meaning and purpose than on defining its location, is what will allow you to adapt to whatever new methods come to pass.

This way of thinking—one where the structures we build derive from what our content means and how it means it, and where pages and documents give way to new forms and approaches—requires a fundamental shift in the way we think about and design for the Web, forcing us to take a fresh look at the very disciplines we’ve embraced as careers: the writing of documents, the architecting of information.

Changing how you work, and how you think, is no small task. So before I leave you to tackle your own organization’s issues and break down your own blobs of content, let’s take a moment to gain some inspiration from the past—and see how keeping a human focus in our work can help us avoid some of the pitfalls of modular, reusable content.

Designing for Change

The Web moves quickly. Apps and mash-ups and services and sites launch daily. Bots continue to take over formerly human tasks. Devices hit shelves, make a splash, and then become obsolete within just a few months.

Things are shifting at a dizzying rate, and our customers and clients expect us to keep up. It’s a tremendously exciting new world, and as we talked about in Chapter 12, “Content and Change,” it’s one where the only way not to let it run you ragged is to stop chasing after the newest new thing and start investing in solutions that are more scalable and adaptable.

In a sense, today’s challenge isn’t so different from what happened in the first part of the last century—a time when mechanization was rapidly changing the economic and social landscape, and people were struggling to make sense of the endless array of new technology around them.

Automobiles, airplanes, ocean liners: the technological advancements of the early 20th century set into motion a new way of thinking about building—moving focus toward engineering, repeatable processes, and modular parts, rather than on designing individual units as complete, immutable wholes.

In other words, people started thinking about how to design for a world that had changed.

Architecture from Within

The plan proceeds from the inside out; the exterior is the result of the interior.

—Le Corbusier, 1923

Shaped by these advancements, and the changes they brought to everything from urban life to warfare, a new movement emerged in art and architecture: modernism. Perhaps the most prominent proponent of this new aesthetic in architecture was the French modernist Le Corbusier, known for his 1923 treatise Towards an Architecture (widely known, until its most recent scholarly English translation in 2007, as Towards a New Architecture). Reacting to the embellished, grandiose beaux-arts style that was en vogue at the start of the 20th century, Le Corbusier called for his peers to develop a new architecture—one focused on designing for purpose, rather than decoration (see Figure 13.1).

Calling the home a “machine for living in,” Le Corbusier emphasized the importance of understanding purpose—of breaking homes down to their elements so that a new approach to designing spaces would emerge: spaces that could be mass produced, and whose structure would endure through those replications.

In this world, homes and communities would trade in decoration—flourishes that didn’t contribute to practical living—for design that embraced the repeatable processes and standardized parts of the modern world.

As part of this new architecture, Le Corbusier envisioned mass-produced housing designed with various combinations of the same standardized fixtures and finishes, creating communities that could be built quickly and efficiently off the same modular designs.

Today, as the people responsible for designing the systems that will support content, our task in some ways isn’t unlike that of Le Corbusier’s mass-production housing. We must design our content’s structure around its purpose, and make it modular and reusable across different applications.

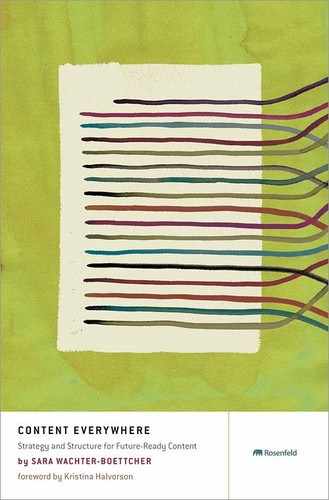

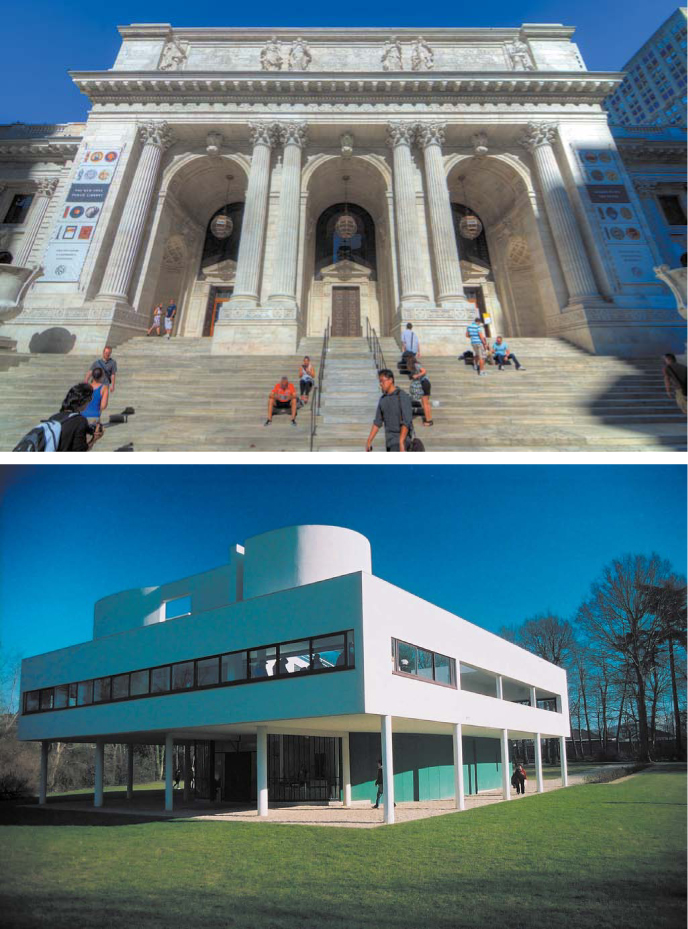

FIGURE 13.1

Beaux-arts detail defines the New York Public Library, built in 1911. Needless to say, Le Corbusier preferred the style of Villa Savoye, a modernist home he built in Poissy, France, from 1928 to 1931 (image by Lawrence Baulch, Creative Commons-BY).

The Problem with Mass Production

Yet this aesthetic of modularity and mass production wasn’t without its pitfalls—pitfalls we must avoid as we wrestle to make our reusable, replicable modules of content work for users.

In fact, Le Corbusier’s harshest critics later accused his “new architecture” of leading to the rigid, uninviting structures of postwar communism in the East and public housing complexes in the cities of the West. In housing projects from East Berlin to East Harlem, millions of humans inhabited similarly towering, bleak buildings built—ostensibly at least—under the principles outlined by Le Corbusier: repeatability, efficiency, modularity (see Figure 13.2).

If the home is indeed a machine for living in, as Le Corbusier touted in Towards an Architecture, then these spaces seemed to define “living” in an incredibly limited way: They included all the necessary components, but none of the necessary life. Though repeatable everywhere and functionally complete, structures like these were devoid of spirit: disconnected from the cities in which they were located, isolating, and unfriendly for pedestrians—“in the city, but not of the city,” as the popular saying goes.

FIGURE 13.2

East Harlem’s Robert F. Wagner public housing project, built in 1958, presents a pretty bleak view of modular, repeatable structures (image by Madame Chaotica, Creative Commons-BY).

This is precisely what we need to avoid with our content. While we want the benefits of modular, reusable content, we’re not running factories that stamp out the same chunks of content, day after day. Instead, as we talked about in Chapter 12, today’s challenge is to be adaptable to a constantly changing landscape.

This means we need content that can be reused across different outputs, yet that feels not just in its medium, but of its medium, everywhere it goes. We need content that can feel in context with anywhere it’s being presented, even if we don’t know exactly where that might be yet.

Simultaneously, we need to keep our content’s liveliness intact as it becomes modular and more automated—a challenge that has long plagued projects that seek to aggregate and collect like content, like the BBC’s nature or recipe websites we learned about in Chapter 8, “Findable Content.” Without a human editor shaping and guiding their production, what separates these hubs of information from a list of links, functionally just fine but practically quite boring?

Content in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

We’re not the first to grapple with challenges like this. In his 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” cultural critic Walter Benjamin argued that the effect of reproduction is often a loss of authenticity—that the “aura” that accompanied the original dissipates as it is copied.

Of course, neither Le Corbusier nor Benjamin could have foreseen today’s world of digital content—a world where labels like “original” and “reproduction” are difficult to affix to information that’s ultimately just an expression of ones and zeroes. Yet this idea that our work—call it art, call it content, call it product—has an aura, a sense of authenticity, is still quite valuable.

Like those acres of monolithic housing projects, carefully subdivided into endlessly replicable units, content that’s devoid of liveliness and authenticity won’t do us any good. As we move towards being more structured and modular, towards making things that can be repurposed and reconfigured over and over again, we must never lose sight of this need for feeling—lest we end up with content that’s functionally adequate, yet unsatisfying and dead.

Keeping the Aura Intact

As technological advancement continues rapidly for us, much like it did for the early modernists, we must learn to keep pace by designing new systems for content—without falling victim to this unaesthetic, cold industrialization. We must build an approach to our work that embraces standard, repeatable systems for content, without rendering that content devoid of the spirit that lends it meaning.

But in an age where reproduction is unavoidable, and even desirable, where and how does the aura—the heart and soul of the content—live? How do we mechanize the means by which our content is published without mechanizing the content itself?

The answer is in not just devising content structures that are universally recognizable, but that also retain their inherent brand, message, and art—the things that make the content itself any good.

This is the real crux of creating content that will endure, serving your organization and users into the future: it must shift and reshape to fit varied devices, contexts, and sites, while also retaining its essence—the substance that defines it and makes it what it is.

Getting closer to content and understanding how its elements lend it meaning and give it purpose, as we’ve learned to do throughout this book, is the only way to keep content from losing its power as its context shifts.

That’s why it’s so critical not to just model content in the technical sense, but to start with the creative sense, as we learned to do in Chapter 3, “Breaking Content Down.” Because it’s only once we understand what our content means for our users—and make structural decisions that support and enhance that meaning—that we’ll make it strong enough to stay intact as it faces shifts in device, location, and layout.

This is also why we can’t assume the same structuring, the same COPE model, or the same markup is going to work for everything and everyone. It’s why single-sourcing all your content, all the time, is likely a pipe dream. And it’s why so many structured content efforts have had a hard time gaining steam outside of niche technical groups.

Instead of looking at structure as a single solution—a one-size-fits-all approach to content—it’s important to consider your content on a spectrum, from handcrafted to fully automated. Some content is truly just for one place, one moment in time. Some must be so human and in the moment that it can’t be robotically yanked from a database and plopped onto a page.

That’s OK.

The real work is in determining which things need that level of human care, and which things do not—and building systems that allow you to make it happen.

Content for Humans

Whether it was a case of unforeseen consequences, bad implementation, or simply flawed ideas from the start, countless buildings were constructed with Le Corbusier’s ideals in mind that stripped the humanness from living—treated a room’s purpose as something cold, sterile, and purely task-oriented. And just as that failed to serve the needs of the people who inhabited these perfectly repeatable, infinitely modular homes, any approach that removes the human touch from our content will fail our users as well.

After all, our goal isn’t to spread our content as far as possible, distributing its seeds onto each and every patch of land we can find. Content everywhere means, at its core, content that lives on, inhabiting many different lives across many different paths, not all of which we can control. It means content that flexes and fits our users, without breaking the things that make it what it is: its provenance, its message, its craft.

Content that has any hope of enduring—of making a lasting impression on a person’s life, values, loyalties, or actions—must matter to the person consuming it. And that means it will never be enough to simply replicate information across every device, channel, platform, or touch point possible.

Instead, if you embrace this more micro approach to information architecture—considering the inherent shape of your content first, then designing human-centered systems that connect the dots and enable understanding—you’ll be able to keep the heart of your content intact, wherever it goes.

The Road Ahead

“Content” can be a dirty word. Vague and vast in its definition, it can come to include nearly anything and everything—so it’s easy to dismiss or to stop bothering to parse its meaning.

But, as we’ve talked about time and again throughout this book, content isn’t homogenous, each molecule the same. It’s layered, rich, and intensely personal. It’s expensive to create, time-consuming to keep up, and impossible to do without.

It’s complex, and it deserves attention and analysis.

Yet we spend so much time thinking about content—full of powerful stories, important information, critical details—as just documents and pages, identical little units where each one is exactly like the others. We’ve failed to take its complexity into account when it comes to how we’ve published and displayed it. And as a more mobile, social, and user-centered Web has emerged, that failure has finally caught up with us.

It’s time we right the ship.

Wherever the world goes with markup, whatever happens with the Semantic Web and APIs and even big hairy problems like media revenue models, the truth remains: You’re going to need content that’s ready for multiple destinations—multiple potential destinies.

In fact, if you even want to be part of your organization’s conversations about those big hairy problems, you’d be best served by understanding your content and all the ways it might get used and reused.

To get there, you have to break down both your content and the organizational hurdles that are preventing your organization from change. You have to focus on getting modular and more flexible without losing sight of what your content means and how it matches your audiences’ mental models.

Without this, it doesn’t really matter whether you live and die by XML, demand a CMS that can handle markdown, or any number of other practical matters. You’ll still be stuck dealing with content that doesn’t stand the test of time, and your organization or client will still feel the pain of every new device and platform and expectation your users develop.

The Internet is going to change. The business world is going to change. And it’s all going to happen very quickly, without a lot of time for big, bumbling slowpoke organizations to catch up. But your content doesn’t have to be left behind. You can start working, right now, to help your organization or clients adapt more quickly, embrace new ideas more easily, and run more efficiently well into the future. You can make content that endures—content that withstands changes to how and where it’s displayed, and still continues to serve its purpose.

If you do, you’ll not only help your organization and its customers, but you’ll also increase your job prospects—and likely your own professional satisfaction as well. If you don’t, you’ll end up stuck, too—unable to bring your skills and experience along as the future continues marching on.

The choice is yours, but the content isn’t. It belongs to your users. It’s time you give it to them, everywhere they want it.