CHAPTER 8

Findable Content

“That’s exactly what I was looking for!”

It’s a pretty good feeling, right? But as content gets unfixed and flexible and spread across all sorts of platforms, it’s also a feeling too many people are missing out on, slogging their way through the muck of content farms and overgrown forests of navigation and ultimately ending up in the expansive fields of user frustration.

Thankfully, you’re here to help them on this metaphor-laden journey—using your content’s structure as your tool.

Don’t worry: This isn’t some smarmy fluff about the latest SEO techniques. It’s a look at findability in many different places, both on a website and off—everything from improving what appears in search engine results to better handling site search queries, faceted search, and related or contextual content.

In this chapter, you’ll see how content structure, metadata, and markup are allowing organizations to make content more findable in many different ways—and, I hope, feel inspired to consider what your own content can do.

More Structured, More Findable

Why does structure help your content get found by your users? Ultimately, it’s because it gives them so much more to find. When your content is an unstructured blob, there’s only so much you can do to make the information inside accessible: You can rely on the keywords within the content to provide enough relevance for search engines to catch on; you can add generic, free-form tags to organize content; and you can build a hierarchical navigation system. And that’s about it.

Once you have meaningful chunks, appropriate metadata, and content stored separate from its presentation, however, you have lots more to work with—because every attribute of the content you store can be used to increase and enhance the ways people can find it. Your metadata can support sort and filter options; your semantic markup can better inform the search engine ’bots; and your shared content attributes can link related content together. And all of this can happen without the effort, time, and expense of chasing SEO tactics or creating carefully hand-curated collections of content.

Let’s look at some examples of each.

Search Engine Findability

Search engine algorithms are constantly changing. That’s partly because their robots’ ability to understand content, context, and relevance is always getting better, and partly because some hucksters are constantly cooking up new ways to game the system, and the engines have to compensate for it by finding new ways to thwart them. In 2012, for example, Google released several updates designed to cut down on web-spam—many of them designed to emphasize content quality and stop over-ranking sites that engage in keyword-stuffing (repeating the same terms over and over just to game the system) and questionable linking schemes.

While lots of SEO companies out there will still sell clients on chasing the white whale of “rankings,” today’s world of personalized search results, social results, and constantly refreshing news means that it’s near impossible to know where you “rank” on the search engine results page for any given term. Instead, you want to consider whether your content is adequately visible to—and understood by—search engines.

The good news is, by this point, you should have a lot of the work already under control. Once you’ve turned your content into meaningful chunks, stripped the non-semantic code from your database, and created markup that tells machines what a piece of information is, then the search-engine ’bots will have a much easier time making sense of it, too.

Keyword-Rich Content Attributes

“What about keywords?” you might ask. Yes, they’re important, but they’re often mystified—like they’re magical terms only an SEO guru can obtain and understand. In reality, they’re simply the words your audience naturally uses when looking for your product, service, or information. If the categories and attributes you’re using for your content are logical to your users, align with their mental models, and match their needs, then they’ll probably match pretty closely to the terminology those same users are likely to type into a search engine, right?

You can confirm your terminology makes sense—and compare potential vocabulary choices to see what’s most commonly used—with some simple research. For example, I did this back at the Arizona Office of Tourism, where we renamed a site section from “What to Do” to “Things to Do” after some analysis using keyword research tools showed that the latter phrase was a common query, while the former wasn’t even on the list.

TIP DON’T FEAR KEYWORD RESEARCH

If you’re new to SEO, try getting a big-picture look at how people look for your product or service online by using Google Trends (http://www.google.com/trends), which lets you compare searches over time for two or more words you think are commonly used by your audience, such as “vacation deals” versus “vacation packages.” You can also get more micro information with one of many keyword research tools, where you type in a seed term and get back a range of words and phrases people commonly use. Try Wordtracker’s free version (https://freekeywords.wordtracker.com) to get started.

We then used structured content and rules to relate each individual listing for various “things to do” to its appropriate city page, automatically creating plenty of content optimized for “things to do in [city name]” for all 400 or so of the state’s cities—without using any of SEO’s spammier gimmicks like keyword stuffing to get there. As a result, traffic from “things to do”-related keywords increased dramatically, and the user experience improved at the same time by making more valuable content accessible in more logical, useful places.

Content Hubs

If you’re working with a site where multiple content types share a single attribute—like my previous example, where businesses, hotels, parks and landmarks, feature stories, and more all shared an element for “city”—then you can also use that shared attribute to create hubs of content around a topic, much like the Sedona page we talked about earlier.

Not only can these sorts of hubs help users find things in the way they want, such as creating itineraries of things do to around Sedona, but they can also help you gain more traction with search engines. When all your content on a topic is aggregated, organized, and maybe even curated together, it creates a canonical presence: the place for Sedona content. Even if you have the exact same amount of content related to a topic, with the exact same keyword density—like we had all those business listings, articles, and other information spread across the site—creating a hub page can improve your SEO results substantially.

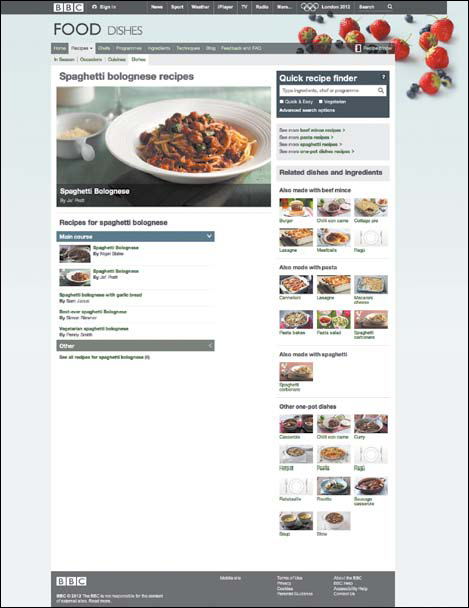

The British Broadcasting Corporation learned how beneficial this could be with BBC Food, a website dedicated to presenting the BBC’s culinary content, like celebrity chefs, recipes, and food-related programs, online. With user experience designer Mike Atherton leading the way, the organization implemented what Atherton refers to as “domain-driven design”—a process not unlike the content structuring we talk about here. In this case, the BBC’s content model placed the “dish” at the canonical center—like spaghetti Bolognese, for example, as shown in the screenshot in Figure 8.1. While there might be half a dozen recipes for spaghetti Bolognese, each from a different BBC-affiliated chef, there’s only one dish.

By creating content hubs around each dish in the domain, the BBC was able to build a central location where users could compare various recipes, explore the chefs and shows affiliated with the dish, understand the ingredients and techniques involved, and more. Meanwhile, this page became extremely relevant for spaghetti Bolognese searches, because it was the canonical source on the topic—leading to much improved SEO results. In fact, after launching BBC Food with this approach, the site saw an increase of more than 150,000 visitors each week from search engines alone—and overall traffic doubled, from around 650,000 visitors per week to around 1.3 million.

Now, there’s more to search engines—and to SEO—than structured content. But if you want to improve your visibility in search for the long haul, without sacrificing user experience or spending tons of budget on SEO consultants, then properly structured, semantic content is a great place to start.

FIGURE 8.1

The spaghetti Bolognese page from BBC Food, the center of the site’s domain model. From here, you can find all spaghetti Bolognese recipes, as well as additional contextual information.

Site Search Findability

Often overlooked by both UXers and content strategists, improving the performance of your own site’s search engine—that is, how easily and accurately your users find the information they want using it—is frequently a simple way to glean immediate improvements to a website’s performance.

Site search data is powerful stuff: it tells you, in users’ own words, what they want from your site and whether or not you have it. By analyzing what your users are typing in, you can see whether there are things they want that you don’t have, confirm whether they’re getting results to their common queries, and—most importantly for this book—make sure the results they’re finding are the most appropriate, relevant ones.

TIP GETTING STARTED WITH SITE SEARCH

For a deep dive into your site search data, pick up Search Analytics for Your Site: Conversations with Your Customers by Lou Rosenfeld, also published by Rosenfeld Media.

Once you start analyzing your site search data, you’ll probably find a whole list of ways you’d like to adjust your search engine’s performance to better meet searchers’ needs. Lo and behold, the better your content is structured, the easier it will be to implement these recommendations.

Remember how we talked about building rules in Chapter 5, “Designing Content Systems”? Well, when you really look at it, your site’s internal search engine just uses another set of rules, combing your site’s content and deciding what the most relevant response to a query should be. And unlike external search engines like Google or Bing, you can change the way your site’s search engine works, prioritizing some factors and deprioritizing others in ways that help the right content bubble up to the surface.

Just like with external search engines, when your content is stored in modular parts, you’re essentially giving your internal search engine more to work with: more chunks, more labels that help it understand what a piece of content is about. But structured content does something even greater for internal site search: it gives you lots of easy ways to tune your search engine results systematically.

One way you might tune results is by content type. For example, while working with a large university, I found that certain types of content, like press releases, were showing up disproportionately frequently in top search results—even when those press releases were several years old, and the query was something general and immediate, like “dorm costs.” Overall, we saw that users’ queries tended to map to a need for immediate information, not historical facts—and because press releases represent a moment in time, they were unlikely to meet this need. Likely at least in part due to this, the number of users who were abandoning the site after seeing a search results page was extremely high.

Tuning search engine performance takes careful attention and a bit of tweaking, but in this case, it was easy to decrease the weight for press releases as a whole—meaning they would still show up in search results, and could even be at the top of the pile for more specific queries where their content seemed especially relevant, but they were much less likely to make it to the top for most general terms.

In addition to prioritizing or deprioritizing whole content types, having content structured into meaningful chunks also allows you to put more or less weight on different elements of content. For example, if you have summaries or abstracts associated with all your content, those fields could be given greater weight in determining search engine relevance—the reasoning being, if it’s in the abstract, then that keyword must really be central to that piece of content, not just tangentially referenced. Or, you might find that you want to prioritize articles or other content that’s been recently published, and deprioritize content that’s older—something that’s much easier to do if your content is structured.

Without structure behind your content, your internal site search will rely on what it can glean from a large content block—in other words, relatively little. This means to tune it to your needs, you’ll typically be less able to make changes to its algorithm—the equation that consistently governs how content relevance is weighted—and instead rely more on hacks: overrides to the algorithm’s logic. And while those hacks are OK here and there, they’re a manual fix: While you can likely implement them for a few highly searched terms, you could do more to benefit the entire site search engine if you put some structure behind it.

Smarter Faceted Search

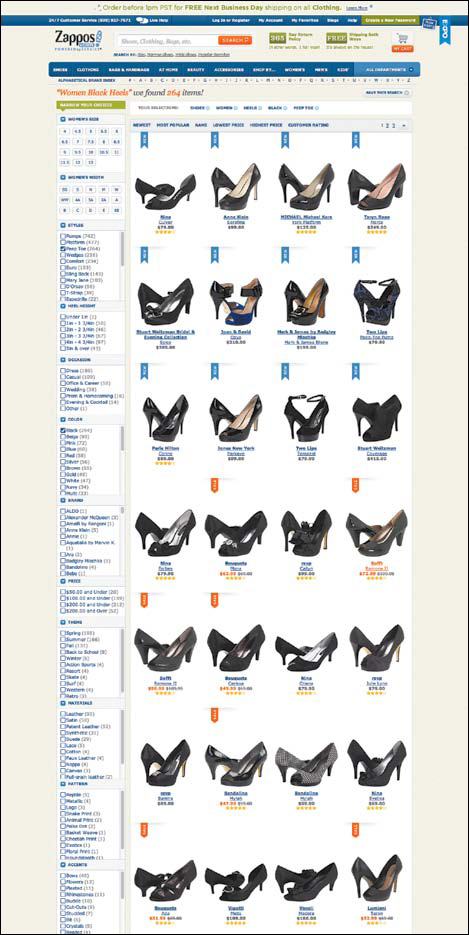

Faceted search, which allows users to sort and filter content using multiple criteria, has been around for years—perhaps most notably on online shopping sites, where you can whittle product results down to those most relevant to your search with criteria like size, color, brand, and price. It’s incredibly helpful, and perhaps even necessary, for navigating large product inventories. Could you imagine shopping Zappos, the online retailer of shoes and other apparel, without it? Even a search for a relatively specific item—a pair of black peep-toe heels, for example—can return hundreds of products (see Figure 8.2).

FIGURE 8.2

Navigating product sites, like Zappos.com, would be near impossible without faceted search, which is powered by structured content—but would benefit other types of content as well.

What online retail figured out long ago is that users wanted to find products in different ways, accessing and ordering products differently depending on their unique requirements or desires, rather than being forced to scroll through all items in a predetermined order set by the site. What the industry also figured out was that this level of faceted search requires structure—because in order to sort or filter by a certain criterion, that element must exist in a separate spot in the database.

Because of this, product listings for shopping are now nearly always structured, and their format is relatively consistent across different sites—making it possible for all kinds of things to work, from Google search results extracting the price of a product you search for without you even clicking through to view it, to those shopping aggregators that allow you to compare multiple sites’ deals on the same product.

Not all kinds of content need this level of personal control over sorting and filtering, of course. But if you have lots of content that’s designed for exploring—think things like recipes, help articles, restaurant listings, and anything else people might want to parse in different ways—you can put your content elements to work to help your users avoid a frustrating needle-in-a-haystack experience.

Related and Contextually Discoverable Content

When I first started working with websites—at the time, for a marketing-focused group obsessed with SEO, lead forms, and conversion rates—it seemed like every single sidebar we recommended was the same: an exposed lead form or a big call to action to buy now.

Needless to say (or maybe not, since I still see so many of them out there), these super-salesy sidebars don’t always work so well—because they didn’t take into account what users actually wanted to do next.

In other places, you see related or contextually accessible content all the time: links to additional articles at the bottom of a story, for example, or similar dishes along the sidebar of a recipe page. But how often is this content actually relevant?

These sidebars and related items lists are often based on free-form keyword tags or automatically generated lists—creating relationships that are assumed, rather than inherent to the content itself. As Atherton found when working with the BBC, this makes for a weak relationship. But when you have structure behind your content, such as with domain modeling, you create an ontological relationship—one built at the deepest level of the content, cutting to the core of its “thingness,” the stuff that makes the content what it is. This ensures related and contextual information is actually deeply rooted to the topic of the page—no questionable keywords required.

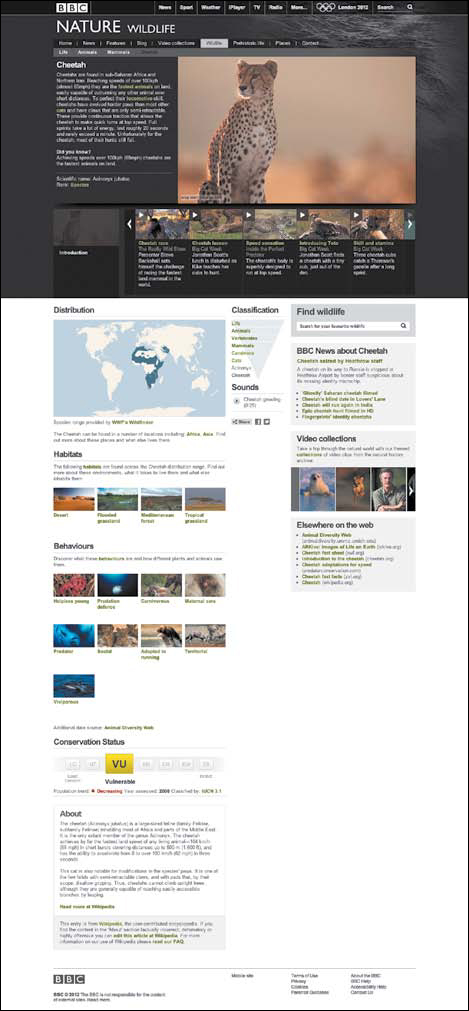

One easy-to-understand example of these deep relationships in action is the BBC’s Wildlife Finder. Because the BBC—and, by extension, much of the British public, who fund the BBC by paying television licensing fees—had invested substantially in creating a vast amount of nature video, the organization wanted to get more mileage out of this content than simply creating massive archives. The team took on the challenge by building a system for relating contextually relevant information based off a well-known historic domain: the Linnaean taxonomy, otherwise known as the animal classification system.

With this, you can visit a page about a specific animal, like the cheetah (shown in Figure 8.3), and from there, easily find videos, news, and links related to cheetahs. In addition, the structured classification system also opens up a wide range of related content options: a quick link up a level allows you to explore the entire felidae (cat) family, while a selection of related animals creates a parallel for exploring similar species, like the lynx.

In addition to using animal classification to structure BBC Wildlife content, the team also derived a system that included other information about animals, including their habitats and behaviors. For example, from the panda page, you can see that a panda lives in a broadleaf forest. By clicking through to the broadleaf forest page, you can see what a broadleaf forest means, as well as what other sorts of animals live there. And all these pages of content are built automatically, using the content’s underlying structure to dictate what’s contextually relevant where.

Finally, remember our introduction to linked data in Chapter 6, “Understanding Markup”? Well, the BBC is making use of that, too. Rather than, say, hiring writers to craft overviews of every animal the BBC has video footage about, the organization relies on content from other sources, accessible via linked data. That is, by structuring content along the same lines as sources like Wikipedia, the BBC can automatically pull in the content it doesn’t have—and isn’t invested enough in to create—from an external source.

FIGURE 8.3

BBC Wildlife’s collection of cheetah-related content and links to other animals, habitats, and more—all pulled together automatically based on their content’s structure.

Curation: The Other C-Word

Content curation has been a buzzword for a few years now, and it’s no wonder. As many sites move toward content hubs and lists of related links like the BBC’s wildlife pages, more than a few have started referring to their efforts as curation.

Problem is, curation is a complicated, often contentious thing. While some marketeers call all automated lists of links “curated,” folks from museums and other curatorial roles often find it more than a little unsettling to see a term from their highly specialized fields appropriated so readily.

In a museum setting, curators do much more than collect like things and put them in a room together. They examine cultural trends or historical objects and extract themes, movements, and influences. They arrange works in a way that highlights and contrasts, or that throws viewers’ assumptions into relief. They select pieces that are individually interesting, but that together tell an even richer story.

In short: curation makes new meaning—it creates something that’s more than the sum of its parts.

Curation is also a very human act—one that requires careful attention, editorial sensibility, storytelling skills, and a finely tuned sense of cultural relevance. It can be seen online in people like Jason Kottke and Maria Popova, who weave together some of the most interesting tidbits they find with their own commentary and cultural footnotes, connecting readers to ideas, art, stories, and more. The robots just can’t manage all that yet (whether we ever want them to is, perhaps, another story). While each is valuable in its own right, it’s quite a reach to equate any of the automated approaches discussed here with true curatorial care.

Finding Soul in Findability

One of the biggest benefits to structured content could also become its greatest pitfall. As it gets easier to automatically compile lists of links that are relevant to a topic, or to allow users to search through data in seemingly endlessly faceted ways, there’s a risk that the experience can become robotic: that the resulting content experiences will be reduced to data, not meaningful stories, information, and ideas. It’s hard to make an automated link list memorable.

While structured content and automatically generated pages may not have the power and nuances of curation, this approach to related, contextual, findable content does offer much more than a basic content aggregation system. By designing content models that fit your users’ own mental models for how information connects and makes meaning, you can design a system that relies on a sort of human-influenced robotic editing—resulting in a collection of information created automatically, yes, but that is informed by human care and understanding. It will never offer the handcrafted, carefully culled experience a fantastic human editor can provide. But it’s a start toward efficiently building collections of content that are more thoughtful, useful, and thematic.

After all, you don’t have the time, resources, or money to apply that level of care to every piece of content in the universe, particularly if you’re trying to make a large repository of information useful, like the BBC did with its archives. Instead, by allowing the robots to do some of the work—and giving them the well-structured content they need to do their work well—you can save your precious human capital for the most important, valuable content.