CHAPTER 3

Breaking Content Down

The challenge of making content more flexible begins with its name: content. Vague and expansive, the term alone does little to explain itself—and makes it easy to assume that any one piece of it is the same as another. But as anyone who’s worked with just a bit of content knows, there’s quite a variety that can exist within those seven little letters. From 140-character Tweets to 10,000-word articles, video clips to thumbnail images, all kinds of things can fall into this big, bursting content bucket.

In order to set your content free from the limitations of generic pages, you need to get much more specific about what that content is—understanding its meaningful dimensions and its inherent form—so you can ensure the way you structure and store it makes sense.

In this chapter, we’ll do the prep work for content modeling by taking a deep dive into our content’s meaning, then:

- Learning about content models.

- Analyzing content types, purposes, and goals.

- Assessing the content elements you have—or need—to meet your goals.

Together, this in-depth knowledge will allow you to identify the priorities, relationships, and dependencies that will guide how you ultimately document your models and modularize your content, which we’ll work on in Chapters 4, “Creating Content Models, and 5, “Designing Content Systems.”

Deconstructing to Construct

If you’re new to content modeling, think of it like this: It’s the process of first understanding the concept of a specific type of content—how your users perceive and understand the various pieces and parts it comprises—and then creating a structure that supports those components and relationships. By modeling, you create a tangible representation of the content that will serve as your guide as you write, edit, design templates, configure content management systems, and more.

Why do all this? Well, content modeling is the first step toward winning the war between “blobs versus chunks,” as Karen McGrane calls them—between content that’s shapeless and fixed and content that’s modular and flexible. In other words, you can’t have content everywhere unless you start with a smart model.

Breaking content down into its logical parts also provides practical benefits right on a single site, including:

- Allowing you to move forward with website and CMS specifications before all the content is complete, because you know what each template should be able to support.

- Giving those tasked with collecting, writing, and editing content a clear list of items to create or assemble.

- Providing user experience and interface designers with concrete elements to incorporate in their wireframes and comps. Most of all, content modeling gives you systemic knowledge; it allows you to see what types of content you have, which elements they include, and how they can operate in a standardized way—so you can work with archetypes, rather than designing each one individually.

NOTE MODELS AND TYPES AND ELEMENTS, OH MY!

Before we get too deep, let’s define some terms. The terminology out there may vary, but in this book, I refer to a content type as the actual thing a user would read or use, like an article, a recipe, or a help guide entry. Meanwhile, content elements are the modules and chunks that make up that content type: ingredients, summaries, teasers, and the like. A content model is the connective tissue between all of them—the expression of how all those types and elements coexist. You can make models of individual content types that show how each chunk of content comes together, which we’ll do next, as well as models of entire content systems, which show how multiple content types are interconnected based on rules and relationships, which we’ll start to tackle in Chapter 5.

A content model typically ends up being documented in a diagram that can get translated to a database and CMS structure. But we’re not quite ready to build a model yet. First, we’ll spend this chapter learning how to deconstruct content along meaningful lines that make sense to users and also map to organizational goals and strategies. Only then will we be ready to document our models and get them implemented.

First Meaning, Then Modeling

Content modeling isn’t unique to today’s mobile, multichannel world. Many IAs have been doing it for years, as have technical communicators, database developers, CMS vendors, and even a content or metadata specialist or two.

The difference is, these efforts often focused more on data storage and retrieval than on the content itself. So today, we’re not going to dive right into making diagrams and specs. Instead, we’re going to spend some time thinking about meaning before we get to modeling. Why? Because while it takes a little bit of technical know-how to implement a model, content can be ambiguous—which means that the art of modeling must start long before the spreadsheets and data tables come out.

As content strategist R. Stephen Gracey puts it, “content modeling is more than fields”:

We find ourselves pushed into the thick of technical specification before we’ve had a chance to imagine what the content is supposed to be and do, let alone how it should be structured.

In my view, we’d be nearer the truth of “modeling” if we took our cues from other disciplines... The sculptor “models” in clay before casting in bronze... The industrial designer creates digital “models” before production... Content must be modeled in this creative sense, as well as in the technical sense.1

In other words, arbitrarily chunking content into parts gives us a model, but it doesn’t necessarily make it a meaningful one. Shaping the right model in the first place takes work.

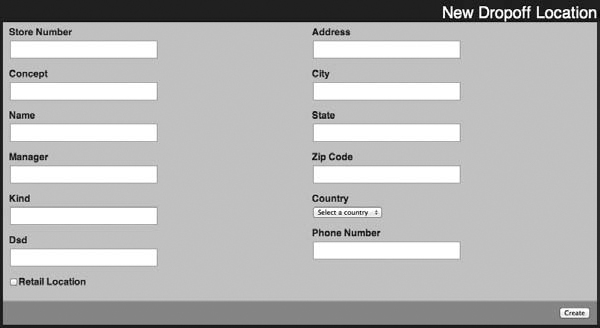

Naturally, I learned this the hard way, as many of us who got into digital work without formal training did. A few years ago, I worked on a project for a large international brand where we were adding retail locations to one of the company’s many sites. Someone from the corporate office sent over a CSV file of location data. It was handed straight to the development team, and the fields in that file immediately became the fields in the CMS template (shown in Figure 3.1) without anyone giving it a moment’s thought.

FIGURE 3.1

Dsd? Kind? When you consider your content’s purpose when making database decisions, you can avoid poor labeling and useless fields like these.

Between indecipherable labels like “Dsd” and open-entry fields labeled “Kind”—kind of what, exactly?—half the fields were either unintelligible or unnecessary. As a result, those responsible for content governance had no idea how to manage these listings effectively.

Fifteen minutes spent thinking about the content within that spreadsheet before the CMS template was built would have solved this problem. But the developer imported what he was given, and that was that.

TIP ADAPTING YOUR PROCESS

How does this close reading of your content fit into your project—and your process? Typically, the earlier you start assessing your content, the more chance you’ll have to use that knowledge later, influencing everything from sitemaps to faceted search and sort features to CMS requirements to content production.

Written down like this, the scenario sounds almost silly. Who let this happen? But in truth, content ends up being modeled like this all the time, in organizations large and small. Maybe even in your own.

We can do better than this, but only when we begin to understand which core elements make our content types come to life—and then share that knowledge with the folks building the physical systems and structures that will support our lively, user-satisfying content.

As content management expert Deane Barker has written, “structuring content can suck the soul out of the authoring process”2 by making those responsible for content stop thinking in wholes and start acting like machines. That’s probably true, but it needn’t be. If those of us who care about delivering great content and experience—like writers, editors, UXers, strategists, and designers—take the lead on making content models that are rich and meaningful, then we won’t have to choose between structure and soul.

Sound good? Then it’s time to get to work by exploring your content more closely than ever and getting at the center of what makes it tick.

A Tale of Two Content Models

To understand why close evaluation of content is so critical for modeling, let’s take a look at a content type you’ve likely seen and perhaps even worked with: a recipe.

Which content elements does a recipe need? If you said title, ingredients, and directions, that’s a start. But oftentimes, there may be much more to it.

I learned this while working on a website overhaul for a quickly growing grocery company. With hundreds of locations and a focus on fresh, natural products, the chain had a large following of fans interested in healthy eating and specialty diets like vegan and gluten-free, as well as a repository of recipes that had been previously published in its email newsletters. To meet the goals of engaging site visitors and reinforcing the chain’s fast, fresh, and healthy brand messages—while driving fans to buy more products, of course—we decided to publish relevant recipes alongside product pages across the site.

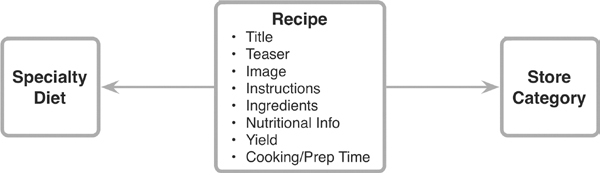

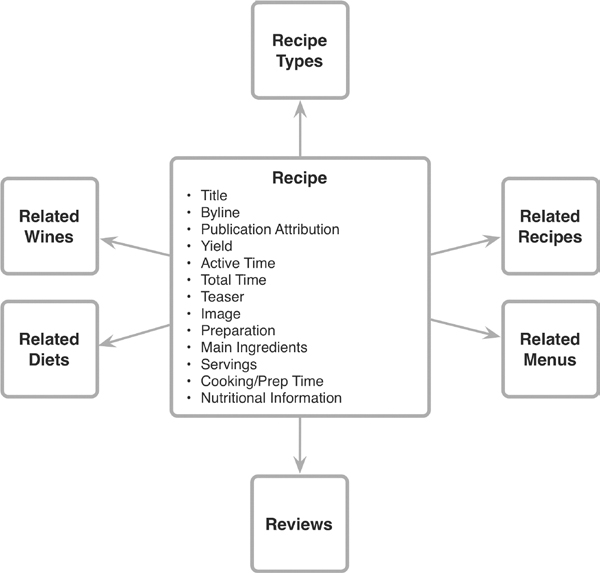

As we began scratching the surface, we saw a whole universe of elements contributing to this content’s meaning and helping us toward our goals. This led us to build a content model (shown in Figure 3.2) that included not just the basics like ingredients, directions, and yield, but also:

- Teasers to provide context and drive interest when displayed throughout the site.

- Nutritional information to support the brand’s health-conscious appeal.

- Specialty tags, like vegan or gluten-free, to assist those with dietary restrictions.

- Cooking and prep time data to reinforce the idea that healthy, home-cooked meals don’t need to be hard.

- Categories that mapped back to the brick-and-mortar stores’ layout, allowing site visitors to easily know where to shop for ingredients when in the store, while also allowing the chain to display more relevant supplemental content to people visiting those sections of the website.

FIGURE 3.2

A grocery chain’s recipe content model, where content elements match the store’s fast, fresh, and healthy branding.

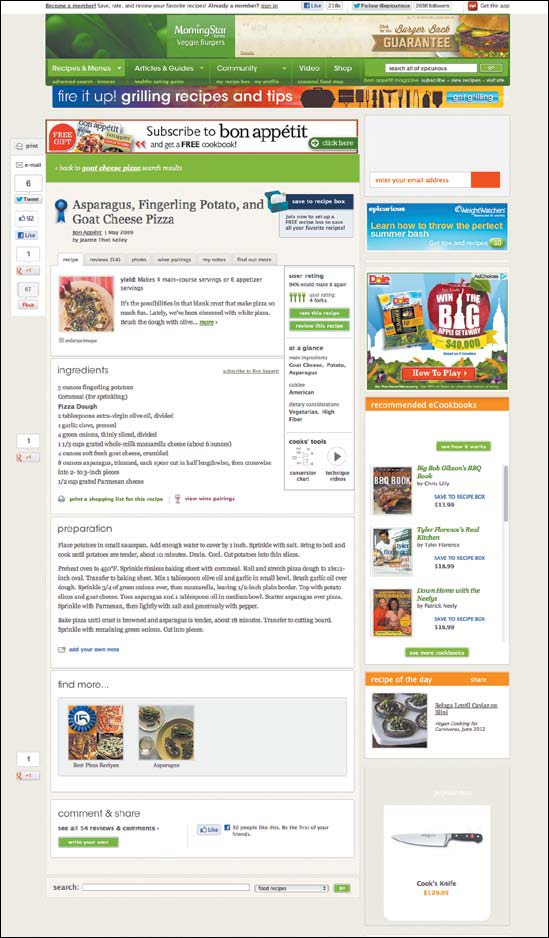

These content attributes aren’t the only meaningful dimensions you could glean from a recipe, however. For a different perspective, let’s look at another approach to the same type of content: the recipe model used by Epicurious, as seen in this top-rated pizza recipe shown in Figure 3.3.

FIGURE 3.3

A recipe for some tasty-looking goat cheese pizza from Epicurious.com.

While we can’t speak to Epicurious’ specific business goals, we can make some reasonable assumptions. First, the site is owned by Condé Nast. As a publisher that runs extensive banner advertising, Epicurious likely wants to increase page views in order to bolster ad revenue, and get recipe hunters to view content on or subscribe to its other food-related media properties, like Bon Appétit—very different goals than our grocery friends, and aims that have led Epicurious to use a long list of content elements, as shown in Figure 3.4:

- Title

- Byline

- Publication attribution

- Yield

- Active time

- Total time

- Teaser description

- Image

- Ingredients

- Preparation

- Wine pairings

- Reviews

- Main ingredients

- Type

- Dietary considerations

- Related menus

- Related recipes

FIGURE 3.4

What Epicurious’ recipe content model appears to look like. Note that it’s both more detailed and just plain different than the model in Figure 3.2.

Two recipes, two very different content models—each seemingly complete. So how do you figure out the right one for your content? What level of detail do you need? To answer that question, we need to take a step back and determine what you’re trying to accomplish in the first place.

Enter, Content Strategy

Content modeling requires you to simultaneously understand your goals at the highest level and get intimate with your content’s most minute attributes, and there’s a pretty big chasm in between. Luckily, there’s an entire discipline dedicated to bridging that divide: content strategy.

At its most basic, a content strategy outlines how content will be used to support both overall organizational goals and audiences’ needs. While there are many approaches to articulating a content strategy and a million ways to customize one for a specific project or problem, it should at a minimum include several items:

- Goals: How will content support your overall strategy? What should it accomplish for your organization? For your users?

- Resources: How much time and money do you have for your content? What skill sets are on hand?

- Key messages: What are the top organizational messages you want content to communicate? What do your users need?

- Voice and tone: How does your brand translate to your online presence? What should you sound like?

If you’re new to content strategy, and don’t foresee your project benefiting from a dedicated content strategist anytime soon, I highly suggest you spend a little extra time figuring this part out.3 It will serve you well as we travel the long road into the future, because each decision you make about content—what you publish, how it’s structured, and where it goes—will come out of this strategy.

Once you understand (and get the team to agree on) what content is intended to do for your organization, you’re ready to start evaluating the types of content you have against those goals. In other words, you’ll now take your macro content strategy, which may affect the entire organization, and apply it, piece by piece, to each of the content types you have.

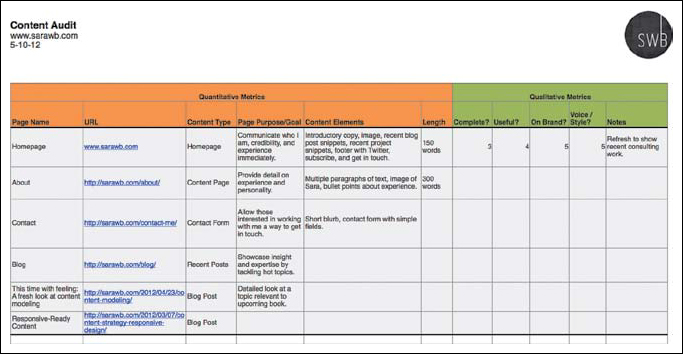

One of the best ways to begin this process is with a content audit—an in-depth accounting of all the content that exists.

Content audits, like the excerpt shown in Figure 3.5, are useful for all kinds of things, but at their most basic, they outline what content you already have and where it can be found. They come in all shapes and sizes, from qualitative evaluations that look for outdated, off-brand, or ineffective content to quantitative reviews of all assets to make sure nothing is missing before defining a new taxonomy for a website.4

FIGURE 3.5

Content audits, like this excerpt, needn’t be pretty. They just need to document what you have, where it is, and any other information relevant to your project.

When it comes to defining meaningful dimensions for your content structures, though, your top priority during the audit phase is to understand the types of content that exist currently—and how consistent their attributes are.

But content types are more than just labels like “articles” or “blog posts”; they’re an exploration of the content’s purpose: What role does it play in achieving your goals? For each distinct purpose you can unravel, you likely have a discrete content type.

To start this process, analyze your content against the following questions:

- Which of your content goals does this type of content support? How? For example, my grocery client wanted to be seen as healthy, so including healthy recipes with prominent nutritional information was important.

- Why would a user want this content? What does it achieve for her? Customer research told this grocery store that shoppers tended to be “assemblers,” not chefs—folks who want to eat fresh, homemade meals without a ton of work. Therefore, recipes needed to show how their products could be used in tasty, easy-to-prepare ways.

- What do you want users to do once they’ve consumed this content? For some organizations, this is easy—after all, “buy more groceries” was an obvious goal for my grocery client. But you might find others that are subtler, such as those relating to education, brand loyalty, or simply understanding.

The level of granularity you’ll need in your content types depends on your organization’s industry and goals. Take the term “article.” With my grocery client, this was a specific enough type, because all articles served the same singular purpose. Whether it was a video showcasing where a fair-trade coffee supplier obtained its beans or a detailed guide to which apples were best for what, every article was designed to demonstrate the brand’s commitment to healthy, natural—yet tasty—foods, and to build deeper connections between shoppers and the products they bought.

But what if you’re working with a media company, like a magazine or news site? Here, the term “article” is uselessly vague: Does it mean features? Editorials? Columns? News briefs? All of the above? These types of content likely accomplish very different things for a publication and for its readers or subscribers. Treating them as a single content type, then, won’t give you the flexibility you need.

In addition to documenting which content types you have, you can also use this moment to analyze whether there are additional types you need. Go back to your overall content goals and ask: Do we have content that is reaching each of these effectively? What’s missing? What about for our users? Have we done enough user research to know what they want, and whether they’re getting it? What new types of content would help fill the gaps?

Just as critical, now’s the time to note any content that seems extraneous. Are there items you simply don’t need? If there’s no organizational or user goal being met by an entire type of content, it’s just clutter. Unfixing it from a page to travel freely across multiple sites and experiences will only further muck things up—for your brand and for the people who encounter it. Cut it now, before it does additional harm.

Once done with your audit, you should have a clear sense of how many types of content you have, and how they’re different from one another—a great starting point for structuring and modeling that content in better, more useful ways.

Common Content Types

So what does a content type actually look like? While your findings will vary, some common examples include:

- Bios

- Blog posts

- Business listings

- Episodes

- Event listings

- Fact sheets

- FAQs

- Feature articles

- Help/user assistance modules

- Podcasts

- Poems

- Press releases

- Products

- Recipes

- Reviews

- Short stories

- Testimonials

- Tips and lists

- Tutorials

This list could go on and on, and vary greatly by industry. Point is, get to know what you’re dealing with, and why it’s important. Because you’ll need this knowledge in order to make smart, useful decisions about how you define its elements, store it, mark it up, and—ultimately—let it travel into an unknown future across varied devices and channels.

It’s important to note that I’ve left user interface copy, also called microcopy or in-line help, out of this list on purpose. That’s because here, we’re focused on the content that takes center stage: the information the site showcases, not the bits of content used to guide people to and around it. Moreover, you’ll likely always need different interface copy for different purposes. But don’t be fooled: UI copy is, indeed, important stuff—and will need careful attention as well.5

Turning Types into Elements

Establishing your content types sets the stage for the next step in breaking your content down: identifying the dimensions of each one. To do this, you need to know which elements exist in a given type of content, and whether they’re complete. A good way to start this process is to evaluate your content through a user’s perspective first: What do they see, and how do they perceive the information? How would you present the content to ease their understanding? Are there obvious distinctions between parts of content, such as titles, teasers or copy decks, subheads, lists, pull quotes, images, captions, or related items?

The specific elements you’ll uncover will vary, depending on the type of content you’re working with. But regardless of what you find, content elements should always accomplish two things:

- Be distinct from one another. A content element can (and likely will) be related to and dependent on other elements, but it should also be distinct from those elements. If breaking content into two elements feels forced, you may be trying to chunk information that’s best left in one piece.

- Represent a unit of information. Each content element won’t tell a complete story—that’s why they’re just chunks, not narrative wholes. But it should always contain enough information to communicate something specific, such as a summary, quote, or list.

Take our example from Chapter 2, “Building a Way Forward.” As NPR began working through the COPE model—that’s “Create Once, Publish Everywhere,” for those who’ve been skimming—the team had some decisions to make about how, precisely, this freewheeling, flexible content they envisioned would be created and organized within their CMS.

When NPR started considering this, the first question was, “What’s our basic building block?” says Zach Brand, NPR’s head of technology—in other words, what brought their content to life?

Initially, the team thought it was shows—the NPR programs like “All Things Considered” or “Talk of the Nation” that you’d traditionally hear on the radio. But after scratching a bit deeper, they discovered that the real kernel of NPR content was the story.

So what makes a story at NPR? Well, that all depends on the story. Some have rich visual and audio assets, some don’t. Some are long, some short. But, says Brand, at their core, all stories include a minimum of four key attributes: a headline, a teaser blurb, a longer description, and a date stamp. Everything else is optional, and depends on what the editor has available, what’s most relevant to the topic, and where it will be used.

Not Just for Big Publishers

It’s not surprising that an organization like NPR—one that has been working with complex content for decades, and that has always packaged its stories and made them available for its member stations’ platforms—has a leg up when it comes to creating editorially driven content elements designed for reuse.

Most of your companies and clients probably aren’t major media organizations with large editorial staffs. If your project isn’t as sophisticated as NPR, don’t worry: There’s still plenty you can do simply by honing a keen editorial eye.

Just as we broke down Epicurious’ recipe into more than a dozen parts, a close reading of just about any content type will reveal multiple distinct elements. Here are a few of the ones I’ve found most common:

- Title/headline: This is a given for most content. Typically just a few words long, though not always, the title is the most common entry point to the content.

- Copy deck/teaser/synopsis: These little tidbits may go by various names, but their structure is typically similar: short, punchy copy that leads users into the content.

- Attribution/byline: Content authorship is an important element, both for legal reasons (e.g., you may be required to attribute the work to the author in order to avoid copyright infringement), and because it’s often useful to relate multiple pieces of content by the same person, such as on a bio page with an author archive.

- Date stamp: News stories, blog posts, event listings, and other types of time-sensitive content usually feature a date stamp, which can mark either when the content was published or when the content is relevant, like in an event listing.

- Subhead: Subheads can be found intermittently throughout a piece of content, demarcating sections of information, or at the beginning of the piece, adding context and detail to a headline.

- Summary: These provide quick overviews of what’s included in a piece of content, such as an abstract for a research paper or a boxed nut graph in a news story.

- Bulleted or numbered lists: Lists are tricky little beasts: sometimes, they’re part and parcel with a larger, more distinct content element. But other times, they’re working their own magic on a piece of content, serving up discrete information, such as specs or product features. If that’s the case, be sure to label them based on what they are—e.g., specs—not just the format they’re in.

- Body content: Beware this content element, as it’s typically where large swaths of text get left to wallow shapelessly. To help prevent this, some organizations break long copy into multiple body sections, each one holding a key theme or narrative. However, many content types will have main content areas where more specific content elements aren’t really discernible. If that’s the case, don’t try to break these into arbitrary pieces—just let it be a longer chunk.

- Complementary content: Often treated as a sidebar—like a timeline that accompanies a trend piece in a magazine, or a quick facts inset that provides a short overview of a story—this content is independent from the main narrative (as in, the main narrative can be read and understood without it). Like lists, when breaking them out, make sure to consider not just where the content lives on a given page, but what that content actually means—and name the content element accordingly.

- Images and videos: While images and videos can certainly be content types unto themselves—you’ve seen YouTube, right?—they’re often simply elements of a larger piece of content, telling one part of a story or supporting other elements. It’s important to decide whether a video can stand alone or is part of a more complex type of content.

- Captions: Working in tandem with photos, charts, graphics, or videos, captions add written context to visual content.

- Transcripts: Transcripts to audio content provide users with a text version, which can be useful for accessibility, SEO, and other factors. While a transcript could live on its own, divorced from its A/V companion, it is often part of a larger multimedia content type.

- Pull quotes: Typically larger, more graphic treatments of a quote pulled from within a story or a key message from within marketing content, pull quotes turn important or compelling information into a visual hook for readers.

- Tags and categories: Sometimes this information is only used for internal metadata (e.g., to help your CMS connect information or enable your CMS authors to find content), but it may be used as external-facing content as well. Tags and categories can provide access to other similar content, help set the scene for users, and increase SEO performance.

These aren’t necessarily the only elements you’ll need to consider. In fact, each new content type you analyze is an opportunity to identify new ones, so an exhaustive list would be, well, exhausting...if not impossible.

Most important, this list is generic—a starting point that will help you begin identifying the natural divisions in your content. From here, you also want to define what these elements are doing in the context of your content—for example, in a recipe, you’d have elements like “preparation time” and “ingredients.” You might have elements like a “testimonial” or a “review.” The more the content’s meaning is reflected in the name of the element, the better.

Finally, as you work through your own content, just remember to look for elements that are both distinct from other parts and that communicate a specific piece of information.

Structure Follows Substance

Once you’re comfortable identifying content elements, your eye will start identifying them everywhere. But don’t get overwhelmed; not all of these elements are of equal importance—and that’s the point. You want to know everything about this content so you can determine what really matters to your users and organizations, because that’s how you’ll know which pieces you want to document more closely and design structures around.

Take our tale of two recipe models. While Epicurious values related recipes and meal-planning guides—great ways to engage a user in more page views—my grocery client cares more about outlining the recipe’s ingredients and departments where they’re found as a means of getting people into the store to shop. And that’s only two of the potential approaches to meaningful models, as illustrated in Figure 3.6.

FIGURE 3.6

The same type of content might need more or fewer distinct elements, depending on what it’s intended to do for your organization and your users. The right answer comes only once you’ve analyzed all your little pieces of content through the lens of a big-picture strategy.

That same recipe could be used in many more types of organizations and serve an entirely different purpose. For example, let’s say a local artisanal cheese producer publishes its own goat cheese pizza recipe. What’s this little creamery trying to accomplish? It may want to add credibility and depth to its brand story, and it probably wants to give fans ideas for what to make with its cheese so they’ll—you guessed it—buy more. Meanwhile, your favorite public television cooking program could share this recipe on its site while promoting its current fundraising drive, featuring a very special pizza paddle as its thank-you gift.

In every case, the recipe could be the same, but what each element is intended to do for the organization would be entirely different—and so, the decisions you make about how those content elements will be handled must be different as well.

That’s why it’s not enough to simply understand the elements that make up a piece of content; you must understand how each of those elements is contributing to the piece’s overall meaning—which we’ll discuss in Chapter 4, as we turn this close content analysis into a documented content model.

Coming Up for Air

OK, we’ve come pretty far, from business strategy to website strategy to content strategy to somewhere in much deeper waters. Time to catch our breath for a moment, get out of the weeds, and remember why we’re here: because we want content that can go mobile, portable, cross-channel—everywhere. Because we want content that’s smarter and more prepared for our users than ever. And because none of those things will be possible unless we truly know what our content holds.

By getting close to your content, asking hard questions, and synthesizing the answers you find, you’re now armed for action. This doesn’t mean every single element you’ve identified and dissected will get special treatment in your CMS, or get a laundry list of rules attached to it. But it does mean you will:

- Understand which elements are most critical, allowing you to prioritize how you design systems to deal with those elements without throwing things like CMS scope out the window.

- Have specific, tangible examples to guide CMS recommendations—and the analysis to back them up.

- Be able to provide content creators with a clear understanding, not just of how to “chunk” content, but why.

- Have the knowledge to collaborate with designers about layout considerations for responsive sites and mobile applications.

- Know what’s important when you start talking with technical teams about things like metadata, markup, and APIs.

- Be more prepared for cross-channel or mobile projects, even if your organization isn’t quite ready for them today.

Ultimately, this deep dive is all about arming you with the knowledge to act purposefully and convincing others to do the same. Without this, no number of CMS bells and whistles or markup acronyms will prepare your content for being set free.

Now we’re ready for what’s next: documenting our findings as complete content models, aligning them with our CMSs, and sharing it all with both the technical teams responsible for making them a reality and the authors who’ll have to use them.