CHAPTER 4

Exploring Why They Work the Way They Do

In this chapter, we will explore why the various primary contracting strategies perform in characteristically different ways. We will ask if there are ways to mitigate some of the problems we see in certain important contracting approaches, EPC‐LS and EPCM in particular. Given the popularity of EPCM around the world, any approaches to improving the outcomes of that particular contract form would be very useful. We will also discuss one of the great paradoxes in contracting strategy: why the best contracting strategies (for owners at least) are less popular than strategies that are more damaging to owner interests in cost and schedule effective projects.

Traditional EPC‐LS (Design‐Build Fixed Price)

EPC‐LS is the contracting strategy that minimizes the joint product nature of capital project delivery. The goal is to divide the project into three clearly delimited phases: owner‐led project preparation, contractor execution, and owner operation. Sometimes, contractor execution extends to starting up the facilities, in which case the contract form is “turnkey.” (We will address whether that is a good idea later.) The clear demarcation of responsibilities is one of the key features of EPC‐LS. It simplifies the management of the approach while creating important limitations as well.

The EPC‐LS form is used in some regions as the primary contracting strategy because government rules make other forms impossible or impractical. Government‐owned industrial companies (so called national companies) are most likely to follow EPC‐LS contracting because it is required or preferred by their government owner. It is the dominant form in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries in the Middle East for national companies and is common for national companies elsewhere in the world as well. Government preference for EPC‐LS is usually ascribed to the desire to make corruption in capital projects more difficult, although I am unaware of any evidence that it does so.1 Sometimes governments make EPC‐LS the only feasible contractual form by requiring government review of contracting decisions down to a very low level—in one case every spending decision over $10,000 USD has to be reviewed. That forces a minimum of contracting decisions and, therefore, EPC‐LS.

When projects are externally funded by financial institutions, the lending syndicate often mandates EPC‐LS. Many lenders go further and prefer a “wrap contract” with a single EPC‐LS turnkey contractor with operational performance guarantees and liquidated damages for late completion. As it is indelicately put, “It is good to have one throat to choke!” In reality, EPC‐LS offers little protection against overruns. The variation in actual‐to‐estimated cost is almost exactly the same for EPC‐LS and other contract strategies. The belief that the contract price is a ceiling on what the project will cost is a form of magical thinking or perhaps just confused vertical orientation. The EPC‐LS contract price is the floor on what the project will cost but certainly not the ceiling! The efficacy of liquidated damages and other penalties will be discussed in Chapter 8. Of course, a lending syndicate's desire to have a single contractor execute a project is not feasible if the project is too large for a single contractor to handle. In fact, about 40 percent of EPC‐LS projects overrun the contractor's bid, and when they do, the average overrun is 17 percent of total project cost with the largest overrun being 150 percent.

When EPC‐LS projects overrun, changes are the culprit (Pr.|t|<.001). The changes are in turn driven by the defects in the front‐end loading (Pr.|t|<.001), especially the FEED quality and the completeness of the project execution planning. In traditional EPC‐LS projects, the first task of the winning contractor is to thoroughly review every aspect of the FEED package. Usually, the contract will require the new contractor to identify and request change orders for all of the deficiencies in the FEED package within 60 to 90 days of contract award. After that point, FEED deficiencies will not generally be accepted as legitimate change order items.2 Of course, what is a “deficiency” is to some extent in the eye of the beholder. The two‐ to three‐month review period is an inevitable feature of the traditional EPC‐LS structure. It is thoroughly disliked by most owners as it is often quite contentious, delays the full start of execution, and pushes up the price if FEED errors and omissions are uncovered.

Many of the alternative EPC‐LS forms, such as design competitions, functional specification contracts, and covert‐to‐lump‐sum contracts, are attempts to avoid the “hard hand‐off” between the FEED contractor and the execution contractor while still maintaining the EPC‐LS format, at least in part. Occasionally, the owner seeks to avoid the hand‐over problem by allowing the FEED contractor to bid and surreptitiously giving that contractor an advantage in the bidding competition. This practice is quite unethical and often deters the best EPCs from entering the competition as they fear they are wasting their time and money.3

When projects are well defined, EPC‐LS does provide more protection against overruns than any other contractual form, but with some important caveats. If the project was too large for the contractor's balance sheet to absorb anything but a smallish overrun, the EPC‐LS form provides little protection to the owner. EPC‐LS projects are a major source of contractor bankruptcies, and in my experience that never works out well for the owner. Also, when a lump‐sum contractor is struggling with the job, quality will suffer unless the owner has a very strong inspection organization.

The Advantages of EPC‐LS

The traditional EPC‐LS offers a simple contractual structure with clear risk allocation if the terms and conditions are carefully drafted. Simple contractual approaches are particularly good when the project itself is large and complex. Remember, contracts are more about risk assignment than anything else.

The approach is less taxing on the owner project organization for certain skill sets. EPC‐LS minimizes owner interface management responsibility, but owners need to be careful not to overdo transfer of interface management. Interfaces with government entities, regulators, etc., should normally be managed by the owner rather than turned over to the contractor. Whether the owner or the contractor will take responsibility for the management of third‐party projects being done in conjunction with the effort should be carefully defined in the terms and conditions and the liability for third‐party performance carefully assigned. If the contractor cannot actually manage that third‐party liability, then remember the principle that risks will go unmanaged if assigned to a party that cannot control them.

The EPC‐LS all but eliminates the need for owner cost control in execution. The owner does not need to deeply understand or practice construction management in this form. But the notion that the owner's team can be very small with EPC‐LS is a misconception. The EPC‐LS form is a fully cost‐incentivized approach to contracting. Every dollar saved is a dollar in the EPC contractor's pocket. Every savvy owner using EPC‐LS knows this and counters the temptation to cut corners with very robust inspection of more or less everything: design standards, procurement of equipment and materials, and field construction. The owner inspectors need to be skilled and willing to confront the contractor on every cut corner they can find. If the contractor is in a loss position on the project, there will still be some things not found, but they will be small. EPC‐LS is a “low‐trust” form of contracting whenever the project is viewed as “one‐off” by the parties and the project is overrunning.

When available, EPC‐LS is perhaps the ideal contract form for highly standardized scopes. When supplier/contractors offer standard package solutions (e.g., for air separation), an EPC‐LS approach plays to the strengths of the suppliers provided that the owner does not require something tailored or unique. A related advantage of EPC‐LS is that the approach can help to control those within the owner organization that love to change things right up to the last minute. When going EPC‐LS, those late changes by the business or operations come with a clear price tag; that in itself is often enough to minimize change.

The fact that EPC‐LS can be very cost competitive in a down‐market environment is a decidedly mixed blessing. It is true that in a down market the low bid is likely to be at or below the “should cost” of the project. It is also true that if the owner has done everything right on the front end and the contractor has a strong balance sheet or a financially strong parent company, the owner may come out ahead. But every owner thinking of taking advantage of this situation needs to understand that there are a lot of caveats and the contractor will be looking for ways to shed risk, increase the price, and decrease his costs from day one. There is no free lunch.

Factors Militating Against Use of EPC‐LS

A number of factors make the use of EPC‐LS difficult or even impossible. The most important limitation by far is the state of the contractor market when a project is coming up for a contracting strategy decision. Busy sellers' markets make EPC‐LS either much more expensive or simply impracticable. When the market is busy, a contractor's need to win any particular bid declines. That enables contractors to more fully price any risk they see in the work.

The problem for owners is that contractors will price risk at a higher level than most owners would. This conclusion simply accords with the first principle of risk pricing: the pricing of the risk is a function of one's wealth position relative to the downside of the bet. Richer people can afford to be less risk‐averse than poorer people. In the industrial world, owners are almost always wealthier than contractors. The financial implications of absorbing a large overrun on a project are profoundly different for a contractor and an owner. On a lump‐sum contract, every dollar of overrun that cannot be avoided is deducted from the contractor's balance sheet. By contrast, every dollar of overrun on a reimbursable project is added to the owner's balance sheet as an asset. The owner is not happy about having to earn against an asset that is larger than expected, but even a large overrun is very unlikely to do serious financial damage to an owner company. A large overrun on even a medium‐sized project could be debilitating for a contractor.

The other factor that becomes important in hot markets is that one may not be able to generate a bid list of three to five genuinely interested contractors. Without at least three bidders, the competition is likely to end up with a high‐cost project, and three bidders is far from optimal.4

The present market is instructive about the differences between owners and contractors. The current market is not overheated in most areas of the world. Even so, contractors are highly risk‐averse. Many major EPC firms are declining to entertain any industrial EPC‐LS work because their financial condition is weak and they feel insecure with fixed‐price work. Many contractors are declining EPC‐LS for infrastructure work as well.

Too Much Time‐Pressure. A second consideration that must be weighed carefully is whether the time required for the EPC‐LS cycle time is going to be palatable to the business sponsors of the project. As shown in Figure 4.1 EPC‐LS projects average more than 130 days from issuance of the invitations to bid (ITB) to bid receipt.5 Larger (more than $500 million) greenfield projects require 215 days on average with a P25 to P75 range from 135 to 267 days. Complex process technology adds to the cycle as well. The bidding cycle is only part of the process. After a winner is selected, the contract terms must be negotiated, and the FEED review process delays true project start even more. If the business case cannot stand the added time, EPC‐LS may be a nonstarter.

FIGURE 4.1 Bid duration drives EPC‐LS cycle time.

Note that the bidding cycles for construction only competitions are much shorter and that there is no difference between lump‐sum construction and unit rate contracts. This becomes important as we discuss other contracting forms.

FIGURE 4.2 The timing of uncertainty reduction is key.

Too Much Residual Uncertainty After FEL. Another significant issue in the EPC‐LS decision is whether uncertainties in the particular project can be reduced very substantially before we need to issue the ITB. The timing of uncertainty reduction should look like the pattern shown in Project A in Figure 4.2. The owner's goal should always be to present a low‐risk project to the contractor community—a project that can be executed quickly and without significant upsets. Smart contractors do not like to enter EPC‐LS bidding competitions for messy projects.

If uncertainty is high at the end of FEL 3 (FEED and execution planning), such as in projects B and C, contractors will not bid, or will bid high, or the resulting contract will not be sustainable as an EPC‐LS.

There are a number of factors that can drive high levels of uncertainty into execution.

- Project unfriendly locations are places in which regulatory approvals are problematic and government interventions in projects during execution are likely and politics are unstable.

- Remote sites and other sites with inherently difficult logistics are probably poor candidates for EPC‐LS.

- Projects using substantially new technology in which significant design changes are likely through much of detailed engineering are not conducive to EPC‐LS.6

- Projects with significant shaping problems such as unhappy partners and other stakeholders, where disruption of execution is likely, should not be attempted EPC‐LS.7

- Finally, projects with poor quality or very incomplete FEED are going to be a disaster in the unlikely case that an EPC‐LS contract can even be had.

Lack of the Proper Skills. EPC‐LS requires the skill to select and manage FEED contractors. That requires a substantial amount of engineering skill. The ability to write a solid ITB and solicit a good number of bids is an under‐appreciated skill set. Finally, as mentioned, a strong inspector cadre is essential to mitigating the quality concerns that always accompany EPC‐LS contracts.

Insufficient Internal Discipline. Some companies should not attempt EPC‐LS simply because they lack the internal disciple essential to keeping EPC‐LS projects under control. By this I do not mean the controls function, but the willingness of all owner functions to get their project scope items addressed in FEL‐2 and not revisit the scope throughout the project execution process. As the old expression goes, the EPC lump‐sum with lots of owner changes is the contract from hell for the owner and the contract from heaven for the contractor.

The contract form depends on allowing the contractor to execute the project without repeated owner intervention. Owners who cannot stomach that should find another contracting strategy. Often changes and interventions lead to conflict with the contractor as well as unending cost growth and schedule slip. We even had one project in which the very reputable Japanese contractor quit the project in the middle of execution, arguing that the endlessly dabbling owner was “not an honorable owner!”

The Operability Penalty. The EPC‐LS form carries a small but consistent operability penalty of about 4 percent of nameplate capacity when compared to equivalent projects executed on different contract strategies. This penalty is based on the second six months production after startup, after startup upsets have been resolved. The hit to operability is not surprising as it is known that cutting corners is an ever‐present danger with the EPC‐LS forms. This result underscores the importance of quality inspectors on the owner team during execution.

Making EPC‐LS Work

EPC‐LS is a perfectly serviceable contract approach with the right owner personnel, the right mindset, and the right situation. The cost‐competitiveness of the form depends on using it in the right circumstances and doing a very good job on the front end. Front‐end loading quality is the primary driver of poor cost competitiveness in EPC‐LS projects (Pr.|t|<.009). And that is not just the FEED portion of FEL‐3 but good project execution planning as well.

EPC‐LS is often considered a very desirable contract approach by owners because they believe it passes risk materially to the contractor. But if the circumstances are not right for EPC‐LS, it often transfers little or no risk to the contractor. It is important to do a sober assessment of the situation before plunging ahead trying to use EPC‐LS when it is not the right strategy. When owners do that, they often end up having to change the contracting strategy at the last minute and end up with a strategy for which they and their project were not prepared.

A well‐chosen and well‐designed EPC‐LS does in fact transfer significant risk to the EPC contractor. But sometimes owners try to take advantage of the situation to transfer all risk of every sort to the contractor. The terms and conditions in an EPC‐LS contract should be designed to clarify risk ownership and management responsibilities but should not be designed to bankrupt the contractor. Sometimes owners will grab a very low bid from a desperate contractor and use their leverage to transfer unreasonable amounts of risk to contractor and then bleed the contractor during execution. In the process, that owner gains a reputation that will make that approach much less likely to generate good bids and more expensive to him in the future. A reputation for being tough but fair is a real advantage for owners in EPC‐LS contracting because over time such owners will attract more and better EPCs to their lump‐sum competitions.

One of the most useful exercises when negotiating an EPC‐LS with the winning contractor is to conduct a risk identification and assignment workshop. One of the most unfortunate practices for owner and contractors is to shy away from frank discussions about who is taking what risk during the negotiation of the terms and conditions. When a risk is not thoroughly discussed, it is easy for both parties to believe it is assigned to the other party. Agree to a set of rules to be followed during these negotiations, especially that whoever has greater control of a risk should be assigned the risk. Projects with clear risk assignment, which is then reflected in the contract language, end up with fewer disputes during execution and fewer claims later.

As owners negotiate with risk‐averse and wary EPCs, remember there are some key provisions that may make the difference between a successful and unsuccessful result. Chief among these are using waivers of consequential damages; setting limitations of liability, especially capping liability at the value of insurance; and providing a clear and fair change order process. Limiting the downside for the contractor in the ITB will entice better contracting firms to bid. Limiting the downside in negotiations make it more likely that the project will actually get under way.

Owners: finish FEED! Only about half of traditional EPC‐LS competitions were preceded by what IPA rated as a complete FEED. The projects that completed FEED were 11 percent less expensive than those that did not (Pr.|t|<.0001). Incomplete FEEDs generate higher low bids. Incomplete FEEDs result in a bid package that looks riskier to the contractors, and they bid accordingly. Incomplete FEED is a purely self‐inflicted wound by the owner; it is utterly unnecessary.

I was recently talking with a student of industrial contracting who said that her objection to EPC‐LS is that it is “anti‐collaborative or at best noncollaborative.” I have heard similar comments from other observers in the past. After watching owner‐contractor relationships over the course of thousands of capital projects in all corners of the world, I do not find EPC‐LS any more or less collaborative than any other contractual form. EPC‐LS does establish some clear boundaries for owner behavior—the owner cannot tell the EPC‐LS contractor how to do their work. But my experience is that owners should never tell contractors how to do their work. Contractors are professionals and should be treated as such. (Do you tell your doctor how your surgery should be performed?) My colleagues and I have seen many EPC‐LS projects in which the owner and contractor worked together seamlessly to solve problems and keep the project moving forward to success. We have also seen “collaborative” contracting strategies such as integrated project delivery descend into acrimonious in‐fighting on the way to failure. Collaboration is much more about competence and mutual respect than the contractual format for the project.

Understanding EPC‐Reimbursable

Reimbursable EPC is a relatively rare contracting form these days for major projects. It is sometimes an owner's contracting strategy of last resort. When no contractor will bid lump‐sum on a project or when EPC‐LS bids come in unacceptably high, EPC‐R is sometimes the fallback strategy. It is often used when high levels of uncertainty persist in a project into execution and an EPCM approach is not feasible. During the hot market periods in the U.S. Gulf Coast and Western Canada regions, EPC‐R was used when other forms, including lump‐sum construction, were simply not available in the market. EPC‐R is used more often when new technology is in play—about 10 percent of EPC‐R projects had some technology that was new in commercial use versus about 6 percent of other projects.8

If EPC‐LS typically has the highest of risk transfer to contractors, EPC‐R surely has the lowest. EPC‐R places more burden on owners to control the project than any other form. Most owners fear the possibility of the contractor “cranking hours” endlessly on EPC‐R projects. Unlike other contractual forms, there is seemingly no built‐in stop to the contractor spending more hours due to low productivity in both engineering and the field. The other EPC reimbursable form, EPCM, at least has the change of contractors for construction even if not for any other activity.

Is the owner fear of “cranking hours” a justified fear? We find it is only to a very limited degree. Most of the time when hours are seemingly being “cranked,” it is because the front end was not completed. EPC‐R projects have more increase in material quantities than any other contract form from authorization to completion. It is true that the EPC‐R contractor almost always executed FEED as well as execution. But one of the major downsides of not having a break between contractors at the end of FEED is that owners are tempted (often with contractor encouragement) to “slide” into execution, blurring the line between FEED activities and execution activities. That tendency is no doubt exacerbated by EPC‐R projects being schedule‐driven more often than any other contractual form except guaranteed maximum price.9

In recent years, even EPCs appear to have shied away from EPC‐R in preference of EPCM. EPC‐R usually involves direct‐hire construction by the EPC. EPC contractors have experienced a good deal of difficulty with direct‐hire projects because the deep level of construction management that is required is now beyond what many can comfortably deliver. Depending on the terms of the contract, EPC‐R often involves significantly more liability for the contractor than an EPCM assignment does. This is especially true if the EPCM has the constructors prime to the owner rather than subcontractors of the EPCM. The EPC‐R contractor may be liable for operational performance problems as well, whereas the EPCM contractor rarely is.

Downsides of EPC‐R for Owners

EPC‐R does not offer many advantages to owners except flexibility.

- It is the most expensive contractual form by a substantial margin. Leaving aside EPCM projects, EPC‐R is 19 percent more costly than all other contractual forms on average (Pr.|t|<.0001).

- It is thought by many to offer significant schedule advantages, but the data do not support that conclusion. It provides no schedule advantage when projects are schedule‐driven or when they are not. When they are schedule‐driven, however, the cost penalty rises to 26 percent (Pr.|t|<.0001). So, one is paying a hefty fine for a schedule advantage that is nil.

- EPC‐R projects also take significantly longer to start up and bring to steady‐state operation (Pr.|t|<.001).

- EPC‐R does not scale well as a contractual form. Larger EPC‐R and EPCM projects are progressively more expensive (more on this later in the chapter).

All in all, this is not a contractual approach I would recommend to any client for a major project except in the most dire of circumstances.

A Deeper Dive into EPCM

As industrial landscape changes go, the development of EPCM as the dominant contracting form has been quite dramatic. That begs the question of why this form has become so popular so quickly. A number of forces are at work.

First, a reminder: the form is actually FEED‐EPCM where FEED stands for “front‐end engineering design.” FEED is the engineering side of the final stage of the front‐end loading process. When FEED is complete, the project moves to full‐funds authorization, aka final investment decision (FID). For a typical project in the process industries, FEED is relatively expensive, typically accounting for 2 to 4 percent of total capital cost. When the EPCM form is selected, the FEED contractor is the EPCM contractor almost all the time (>95 percent). When the FEED contractor is not selected for the EPCM work, it is usually because the FEED contractor and the owner are not getting along.

The cases in which the owner is so unhappy with the FEED contractor as to end the relationship at FEED tend to be highly problematic projects. The core problem is that as soon as the FEED contractor knows it is not going forward into execution, the already problematic FEED process slows down, and the contractor often withdraws his best people. Often the actual contract is of almost no help at all here because the contract did not lay out with enough specificity what all the FEED deliverables were required to be and did not include any consequences for failing to get the work done in a timely way with quality. Every FEED contract should be written so that it is enforceable as a stand‐alone contract. “Off‐ramps” are difficult to write well but are important for a number of contract types.

Because it is an FEED to EPC form, EPCM avoids one of the most difficult transitions for capital projects: changing contractors at the FEED‐to‐execution point. Although FEED is considered part of the “front end,” it is actually more akin to execution engineering than it is to planning. FEED entails completing all of the engineering drawings that will be picked up and detailed in the next phase. The plot plans, the equipment layouts, the piping and instrumentation diagrams, line sizes, the electrical (single) lines, and the heat and material balances are all part of this work. The break between FEED and execution is largely artificial when considered only from the engineering perspective. When contractors are changed at the FEED‐to‐execution gate, for whatever reason, the new contractor needs to thoroughly review the work of the FEED contractor and almost always finds it deficient in a large number of respects. This finding seems to be completely independent of the actual quality of that FEED package! The result is lots of changes, sometimes important and sometimes cosmetic, and a slowing of the project. This transition costs the owner money and time and is thoroughly disliked by most project teams.

If the owner has not planned to change contractors after FEED, the change is very disruptive because new contractors have to be prequalified, and a tendering process has to be initiated.10 Alternatively, a contractor is selected as a sole source, but that is not a good solution either.11 So, the most important advantage of F‐EPCM is that it avoids the FEED‐to‐execution transition.

There are reasons other than the avoidance of transition for owners to like EPCM. As an EPC contractual form, EPCM is a “one‐stop shopping” exercise. Only one contracting decision has to be made; all the others are usually the responsibility of the EPCM, including the selection of the construction contractors. In practice, this means that owners feel like they require little or no construction expertise. Decisions such as when to start work in the field, selection of subcontractors, interface management, controls, and so forth are all considered responsibilities of the EPCM, with the owner providing guidance and consultation but not active management. The owner avoids all of the inspection challenges associated with EPC‐LS. EPCM reflects the reality of today's industrial company projects organization: profound weakness in knowledge of construction and field management practices. The out‐sourcing of construction management that started in Western countries in the late 1980s made contractual approaches such as EPCM inevitable in the 21st century.

The other positive of EPCM is that contractors really like the form, even more than EPC‐reimbursable. Contractors generally tout the form to owners as the best contracting strategy for any and all projects. Contractors' preference for EPCM is understandable: it provides them work with essentially no risk but with a number of avenues for profit, which we will discuss a bit later. The EPCM form also relieves the contractor of having to do direct‐hire of construction labor12 and the full and complete construction management that goes with it. EPCM has significant pluses for both owners and EPCM contractors. But when owners are saying “EPCM is the best way to go!” and contractors are saying “EPCM is the best way to go!” somebody ought to be asking “What's wrong with this picture?” So in keeping with the mantra of “there's no free lunch,” what are the downsides of EPCM?

The Downsides of EPCM

As discussed earlier, EPCM is an expensive contractual approach for owners. At any project size, EPCM is less cost‐competitive than EPC lump‐sum by 5 to 10 percent, depending on project size.13 And this is despite that, unlike EPC‐LS, EPCM is transferring little or no risk to the contractor! The EPCM form is much less cost effective than the split forms—more than 13 percent on average. The EPCM form has more cost growth than EPC‐LS (Pr.|t|<.006), and there is no difference in schedule slip. Therefore, the desire for predictability is not a reason for owners to prefer EPCM over EPC‐LS. Cycle time14 is about 9 percent shorter for EPCM than EPC‐LS (Pr.|t|<.01) due to the long bid cycle associated with traditional EPC‐LS between the completion of FEED and start of execution. There is no difference in average execution time.15

The biggest problem with EPCM from an owner's perspective is that cost performance degrades very rapidly with project size. Figure 4.3 provides the relationship between cost effectiveness and project cost for three types of contract approaches: EPCM, EPC‐LS, and the split forms. Both EPC‐LS and EPCM degrade with project size, but EPCM degrades at a much faster rate. The split forms, however, show no relationship between cost effectiveness and size at all; they maintain their superior cost effectiveness as well for megaprojects as for smaller projects. Ironically, EPCM becomes more common as projects get larger, while split forms become less common.

FIGURE 4.3 The scalability of cost performance varies greatly by contracting strategy.

Why EPCM Contracting Is Problematic

When I say that EPCM contracting is problematic, it is only problematic for owners. It has probably been instrumental in keeping EPC contractors afloat financially over the past decade. But why is EPCM so problematic for owners, and what, if anything, can be done about it?

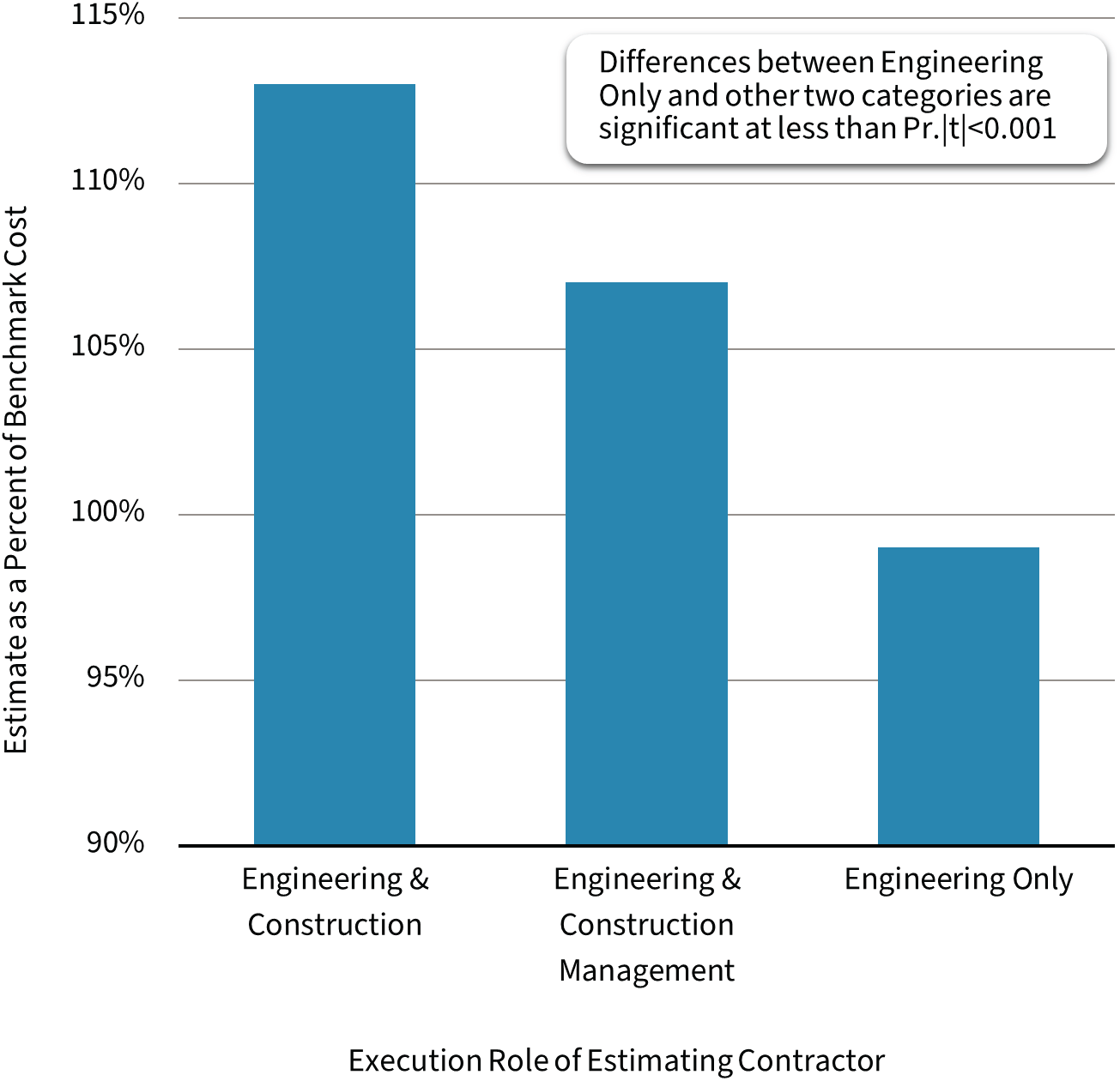

Because FEED is almost always included in the remit of the EPCM, the project's cost estimate and schedule are developed by the EPCM. It is the cost estimate that is key. When contractors who are going to execute develop the cost estimate, they are strongly incentivized to estimate high rather than 50/50. This is not a matter of evil intent; this is just a matter of common sense. As a contractor, would I rather underrun or overrun? Would I rather have more money in the engineering and construction management and construction accounts or less? Figure 4.4 provides the obvious answer to this obvious question.

FIGURE 4.4 Contractors make higher estimates for themselves.

When contractors make the estimates for projects in which they are going to execute engineering and construction, the estimate is 13 percent higher than the expected value of the estimate or engineering and construction management, and the estimates contain 8 percent more money for the total project than cases in which the contractor is going to execute engineering only.

Why doesn't owner estimate validation remove the excess money in the contractor's estimate? When owners went through a validation process on EPC‐R and EPCM contractor estimates, they removed little or none or the overestimated amounts. When the FEED contractor was going to execute engineering only, owner validation resulted in systematic improvement of the estimate (Pr.|t|<.02). What this tells us is pretty simple: when contractors have a very strong incentive to fatten up cost estimates, they will likely to do so and will do so in ways that are difficult for owner validation to find. This phenomenon is merely the principal‐agent problem at work. It is also worth mentioning that the desire to plump up the estimates will occur regardless of whether additional incentive payments are employed. It is just a fact of the situation, and it erodes the cost effectiveness of EPC‐R and EPCM strategies. The owner weakness that makes this process possible is the inability of most owner estimating functions to generate a bottom‐up detailed material takeoff‐based estimate. Because they do not know how to make such an estimate, they do not know how to find fat and errors in such estimates whether they are “open book” or not.

Owners' interests and contractors' interests do not, cannot, and never will fully align. As discussed in Chapter 3, even owner functions are often not fully aligned. There is another fact that really seals this issue. When owner personnel do EPCM, the projects results do not look like EPCM projects. Instead, the results look just like Re/Re or Re/LS projects, depending on how construction is contracted. A few owners maintain detailed engineering capability in‐house, and those owners usually execute F‐EPCM on their projects. They do not overestimate the projects. The projects are much more cost effective than EPCM, but the work structure is otherwise identical to an EPCM. The only thing missing is the principal‐agent problem.

Another disturbing aspect of EPCM from an owner's viewpoint is that the form becomes progressively more expensive with project size (Pr.|t|.004). This is a tendency more pronounced in EPCM than any other contract form.16 Part, but only part, of the explanation is that the estimates are fatter with size. Given the incentive structures at work and the decreasing efficacy of validation as a function of size and complexity (there are more places to hide money subtly), this result is not surprising.

The big difficulty with EPCM is not the F‐EP portion of the work; that is clear enough. However, the CM part frequently is not. Construction management is a general term that applies to a broad array of field activities, ranging from very high‐level progress reporting to very detailed hands‐on management responsibilities. The following is a short list of activities and functions that fall under the rubric of CM:

- Planning and sequencing of construction

- Ensuring timely completion systems for turnovers to ops

- Interface management (mostly between construction contractors on‐site)

- Work package planning: primary and backup tasks planning and tools

- Quantity surveying

- Progress measurement and reporting

- Change management

- Review and approval of submittals to the engineer

- Taking of questions for design and tracking responses

- Safety program—planning and execution

- QC

- Inspection and testing, such as weld tests, hydro testing, etc.

- Construction equipment leasing, maintenance shops, sometimes provision of certain equipment operators as well

- First‐line gang supervision

- General foreperson

- Materials management

- Receipt of equipment and materials inspection

- Yard management

- Lift planning

- Specialty contractor management

- Scaffold

- Paint and insulation

- Dining areas

- Labor camp

This list is not exhaustive, but the point should be clear. CM can range from just a few of these at a high level to every one of these activities. How much CM is required depends very much on the strength of the general construction contractor or the disciplinary contractors who are hired to construct the facilities. When the EPCM contract is signed, generally prior to the start of FEED, none of the actual constructors have usually been identified and qualified. If they have been identified and qualified, they may turn out to be unavailable or uninterested in bidding when the time comes later in the project. The contract may list and the contractor may promise every CM service imaginable. But that doesn't govern the contractor's assumptions about what will really have to be staffed. If the EPCM underestimates the range and depth of CM that will be required, the contractor will need very good bench strength to be able to meet the unexpected challenge. This is where the type of economic entity contractors must be remembered: carrying a strong bench in a professional services organization is a recipe for bankruptcy.

If the EPCM that was selected at the beginning of FEED assumed that the level of CM required would be relatively shallow, the contractor may be woefully unprepared if the construction contractors selected are not able to carry most of their own CM. This sort of mismatch of expectations about the depth of CM that will be required is the single most intractable problem that we see in this contracting form. As projects get larger and more complex, the probability of a mismatch of expectations and reality seems to become almost a certainty. As the number of construction contractors increases on the site, the interface management challenges increase exponentially, and it always seems that at least one of a large number of constructors will turn out to be less competent than expected. The EPCM firm is often not equipped to rescue the situation.

Constructors Prime to Whom?

Another issue that comes up repeatedly in EPCM is whether the construction contractors should be prime to the owner or subcontractors of the EPCM. There are arguments to be made both ways. Some argue, quite plausibly, that the constructors should be subs to the EPCM because they will be supervised by the EPCM, not the owner. Having the constructors prime to the owner could introduce a confusion of authority and accountability. The EPCM directs subs on behalf of the owner as the owner's agent. But the owner must often have direct contact and direction authority over the subs, especially when they are working at the site of a pre‐existing asset.

Both the owners and EPCM sometimes make counterarguments to the constructors being subs. The EPCMs argue that if the constructors are subcontractors to them, it could create some liability for them around construction quality and operability that they do not want. The EPCMs often are resisting that potential liability for causing delay or disruption to constructors' work, wanting theirs to be an entirely risk‐free contract. The owners sometimes complain that when the constructors are sub to the EPCM, they are not allowed to interact effectively with the constructors. The EPCM structure can facilitate playing the blame‐game—shifting responsibility away. When the construction contractors are prime to the owner, they have no links to the construction management entity. Any poor management by the EPCM relieves the constructors of responsibility but creates little risk for the EPCM. Any direction provided by the owner to whom the constructors are legally linked carries no risk for the EPCM and can be used to shift blame. The data do not provide us with any guidance here, which is another way of saying it doesn't make much difference. But expect it to be an issue.

Making EPCM Work Better

After reviewing the detailed histories of more than 300 EPCM projects, I see nine steps that owners can take that will systematically improve the outcomes of these projects. These steps will not eliminate the problems but at least will mitigate them.

- As we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 7, it is important to prequalify potential F‐EPCM contractors. EPCM contractors are selected without prequalification more than in any other contractual form. Be clear that this is not a recommendation to have a formal competitive bidding process for F‐EPCM work; it is rather to fully review the field before you make a selection of the F‐EPCM contractor. Owners learn important things during the prequalification process that may cause them to look beyond the contractor they were intending to hire sole‐source.

- Finish FEED completely before mobilizing design. That means completing all of the P&IDs, not just the inside battery limits portion. It means all the line sizes have been checked, the heat and material balances are fully closed, and all utility requirements are fully known and specified. The failure to complete FEED, which occurs in nearly 40 percent of EPCM projects, adds 10 percent to total installed cost (Pr.|t|<.0001) and is completely unnecessary. Because the FEED contractor will carry on into execution, it is too easy not to complete the FEED; it seems unnecessary. But without completed FEED, there is no quantities baseline for the project, maintaining control of engineering hours becomes more difficult, and work will be done out of order and therefore done more than once.

- Validate the estimate made by your FEED‐EPCM thoroughly. Challenge the bulk material quantities—it is the most common and insidious place to hide money. Benchmark the engineering hours by discipline. Carefully look at all the key ratios by material: bulks‐to‐equipment, engineering hours to bulks, engineering hours per piece of major equipment, labor hours to bulks, CM hours and cost to field hours, etc. If your EPCM balks at giving you complete access to the estimating information, you have selected a predatory EPCM.17

- Work with the contractor at the start of FEED (or even before) to assess the construction market and the capabilities of the general contractors (GCs) and disciplinary construction contractors to understand what depth of construction management will be required for the project. Make the decision about whether a GC will be needed early and start the prequalification process for GCs. If deep CM will be needed by your EPCM contractor, start discussing the staffing requirements during FEED, not later.

- Again work with your assessment of the construction contractor market, and decide what construction contracting strategy will be used if a GC is not going to be employed. For EPCMs, unit rate contracts are the most cost effective—about 8 percent more cost effective on a whole project basis (Pr.|t|<.04). Lump‐sums are directionally cheaper as well. Straight reimbursable and T&M contracts are the most expensive. Recall the principle that says that risks should be assigned to the party most capable of managing those risks. The construction firms doing the work are more capable of handling field productivity risks than any owner as long as the engineering and materials are available.

- Do not attempt to do EPCM by directly contracting disciplinary subs if the disciplinary construction contractor market is so thin that many subs will be required to get the work done on any one EPCM contract. The EPCM will be overwhelmed with interface management problems. When you have a large number of contractors working side by side doing construction, it is almost certain something will go badly wrong. Go with a GC instead, preferably with a unit rate or lump‐sum contract where available. Then allow the GC to manage and coordinate any disciplinary constructors as needed.

- As discussed earlier in this chapter, when smart owners use EPC‐LS strategies, they do very detailed and complete reviews of risk and risk assignments with the EPC during the negotiation process. Unfortunately, we rarely go through the same exercise with EPCM contractors. Part of the reason we do not do so is because the EPCM contract is usually negotiated before the start of FEED when project execution risks seem far in the future. Go through the same risk assignment exercise for EPCMs. Owners should not automatically be agreeing to a zero‐risk‐to‐the‐contractor EPCM form. At a minimum there should be target hours for engineering and CM (separately) that result in a loss of overhead contributions if those hours are exceeded without owner changes.

- If the owner chooses to be schedule‐driven when using an EPCM form, be clear that there is a very sizeable penalty for being so—an average of 8.5 percent of total installed cost. The penalty for being schedule‐driven is higher for EPCM than any other form except EPC‐R.

- Finally, owners have to exercise more discipline about allowing work to go to the field or fabrication yard too early. My advice would be never go to the field until after the final HAZOP is complete and changes incorporated and second model review is completed and changes incorporated. Then do a full review of procurement status. Understand exactly what is going on in the shops fabricating steel and pipe for the project. Then and only then, if everything looks sound, trigger field start. Owner project teams need to explain to the business sponsor that if the contractor attempts to go around the team to the business sponsor to suggest getting the field start sanctioned, they are doing so for their benefit, not the owner's.

EPCM is the single most popular industrial project contracting strategy in the world. Despite its many drawbacks, that is probably not going to change anytime soon. Therefore, it behooves all of us to do the things necessary to make EPCM as effective a strategy as possible.

Understanding the Split Strategies

Just as a reminder, there are four split strategies: Re/LS, Re/Re, LS/LS, and LS/Re. The last of the set is not used very often (about 2 percent of projects) and sometimes came about when the LS/LS strategy unraveled because construction contractors would not work lump‐sum. However, the LS/Re was nonetheless more cost effective (97 percent of industry average) than any of the EPC strategies. Because LS/Re is employed so rarely, we will not bother discussing it as a separate strategy.

The common feature of all split form strategies is the contractual break between engineering and procurement on the one hand and construction on the other. That break has a profound effect on the cost effectiveness of projects. For industrial companies making commodity products, the cost advantage of the split forms can over time provide a substantial boost to their return on capital employed (ROCE), which is one of the core financial measures of company success. Furthermore, as we saw in Chapter 3, the split forms can deliver on schedule‐driven projects as fast as or faster than the EPC strategies. In this section, we will explore the advantages, disadvantages, and challenges of using these generally superior contract strategies.

Split Form Advantages

There are a number of advantages in using split form contracting beyond superior project performance. Perhaps most important, owners are able to maintain control of key project decisions. Most important, when a split strategy is used, owners really do control the decision about when to start construction or fabrication work. In today's industrial projects world, engineering is chronically late. That means that the planned start of construction dates are assuming more complete engineering and procurement than are actually achieved most of the time. Overly early start of construction drives labor productivity into the ground because materials availability and design will not support the intended pace of construction. That makes the decision about construction start date very important to healthy projects.

In EPC forms, the owners think they control the field‐start decision, but they rarely really do. The incentive situation for an EPC or EPCM contractor is clear enough: getting into the field benefits their cash flow. When the contractor says “We are ready to start construction,” it is very difficult for the owner to say otherwise. There is a fundamental information asymmetry. In more than a few cases, we know of EPC‐R and EPCM contractors who went around owner project teams who were resisting starting in the field to tell the business sponsor that the project team was “dragging its feet” and costing the project “precious time.” In split forms, that pressure from the contractor is not there, although the pressure from the business sponsor may be.

In split forms, owners control the selection of construction contractors. That can be good or bad depending on the construction knowledge of the owner, but generally I believe that encouraging owners to have more and better understanding of construction is a good thing.

Split forms offer more flexibility than EPC forms. Better use can be made of whatever construction capability exists in the market. One can go with disciplinary contractors, a general contractor, or a mix of GC and subs. Usually, we can avoid the worst construction contract approaches—reimbursable and time and materials—and select lump‐sum or unit rates. They have the advantage of making craft productivity the responsibility of the constructor instead of the owner. In EPC‐R and EPCM forms, reimbursable or T&M is used most of the time. With their great flexibility and owner control, split forms offer a lot more opportunities to use local contractors.

Split Forms and Modularization

There is another benefit that we at IPA did not understand until looking at these data: split forms using a heavy degree of modular construction are significantly cheaper than EPC forms using modular construction. When looking at modular construction in the past, our conclusion was always that modular construction cost a bit more than stick build except in cases in which labor was abnormally expensive or not available in sufficient supply to do the job in a timely way.18 When we look at the EPC options (LS, R, and CM), modular construction is about 4 percent more than industry average cost, and the result is significant even controlling for FEL (Pr.|t|<.04). But looking only at the split forms using substantial modularization, the cost index is almost 6 percent below industry average, even controlling for FEL, and the result is very robust statistically (Pr.|t|<.0001).

We can only conclude that intrinsically a high degree of modularization usually results in a less expensive project for someone. When the engineering firm contracts with the fabrication yard, it appears that more than 100 percent of the savings associated with modularization goes to the EPC. When the fabrication yard is prime to the owner, the savings go to the owner. The delta is a hefty 10 percent of total installed cost. The engineer's role should only be answering questions about their own design. Then have the setting and finishing contractor prime to the owner with your own CM, with a GC, or with a hired CM firm.

Finally, and probably the biggest advantage to the owner, the split forms avoid having an EPC set their own cost estimate. As we showed in Figure 4.4, when a firm doing EPC‐R or EPCM does FEED, the cost estimate is 8 to 12 percent higher for the whole project. Most of the time, all of that money gets spent.

Disadvantages and Challenges of the Split Strategies

The largest burden of the split strategies is that the owner team and owner project organization must understand construction management. This does not imply that the owner team must do the construction management in split form projects. The owner can hire a firm that will do the CM work or the owner can hire a GC who will do overall CM, execute part of the work with their own organization, and subcontract the things the GC does not want to self‐perform. But the owner needs to understand CM deeply enough to orchestrate the different scenarios. It is very likely that the exact implementation of split strategies will change from project to project.

This is not a matter of having a cadre of good construction managers, although it is part of the calculus. This is a matter of understanding how construction of complex engineered facilities actually works and the things that will be necessary to generate a smooth construction process for a project. Unfortunately, a good many owners think they know construction management more deeply than they actually do. For example, we have seen too many owners who require that the constructors follow the Primavera® schedule that was laid out in front‐end loading. But Primavera® does not reflect the way construction is actually done.19 We have seen owners who dabble in some part of CM. For example, they decide they can do materials management for construction contractors because that will be more cost effective. The result is no one can find anything. We have seen procurement organizations that involved themselves repeatedly in a project for which the engineering contractor is responsible for procurement. Sometimes owners decide to do a “bit” of interface management. When the owner internally is not coherent, the owner/contractor interface cannot be either.

Owners must understand how constructors effectively monitor their progress, usually by the use of material installation rates, so the owner can understand whether the constructor he is prequalifying for the project is actually competent. When using split strategies, the owner will be responsible for selecting the constructors, not the engineering firm. In many cases, the owner will be responsible for doing CM and in others selecting a competent CM or CM/GC. Unless a GC is going to be used, the owner must know how to select the support and specialty contractors as well—scaffolding, heavy lift, etc. All of this takes knowledgeable people. However, the advantages of being able to use the split contracting strategies are so great that it is well worth the investment in people.

To manage split strategy projects effectively, the owner must know how to manage the transition between engineering and engineered material procurement on the one hand and construction on the other. In split strategy projects, the engineering firm (or in‐house detailed engineering organization) will be developing packages for the purposes of bidding the construction work, usually by discipline—civil, mechanical, E&I.20 The owner must then evaluate those bids and select the constructors.

One of the issues that actually comes up in every form of contracting is how to get good construction input into the engineering design of the project and into the FEED where engineering work should be sequenced. A clever way of doing this that we have seen practiced on split forms more often than in other forms is to invite the potential constructors to comment on design and sequencing as part of the prequalification process. We have seen the same process used with fabricators in modular and offshore construction as well. The constructor/fabricators appear willing and even eager to cooperate with this process because out of sequence design and design features that will create constructability challenges are among their chief complaints about engineering firms.21

Owners using split form contracting must also understand the constructor markets in which the project will be executed. Like politics, construction is always local. If an owner works in many places around the world, an in‐house infrastructure will have to be built to maintain knowledge of local construction markets and local norms with regard to construction contracting. The upshot of all this is that owner teams need to be somewhat larger in execution for split strategies than for EPC approaches.

The greater burden that the split strategies place on owner organizations is why the paradox of more effectiveness and less use exists. Given the size of the savings involved, however, the owner would come out well ahead to hire and retain the staff needed to execute split forms well. Split strategies are becoming more popular at a rate of about 1.4 percent higher use per year since 2000 (Pr.>|t|.0001). But that doesn't mean they are popular or that all owner users of the strategy are competent to execute it. Increasing use of split forms in the future will require strengthening more owner project organizations in the area of construction management.

Differences Among Re/Re, Re/LS, and LS/LS

There are some important differences in how the various split forms work. Re/Re is the most robust of the three forms. It provides very good cost and schedule performance, very little cost growth (4 percent), and less schedule slip than average (15 percent, which is a lot but still less than average). Re/Re is especially cost effective when unit rate construction contracts are used but are cost effective on average in any case. The overall performance is dependent only on completing front‐end loading with good quality. When speed in execution is important, Re/Re becomes the fastest of all contracting strategies (82 percent of industry average) with no degradation of cost performance. By contrast, the Re/LS and LS/LS forms are more sensitive to site knowledge and to team continuity than Re/Re. Because it does not use lump‐sum construction, there are fewer “gotcha” items.

Under schedule pressure, the Re/LS responds just as well as the Re/Re, but LS/LS does not. When schedule‐driven, the LS/LS form gathers very little speed, and the cost performance degrades from .92 in the non‐schedule driven case to .98. Re/Re and Re/LS show no cost degradation at all. The culprit is the poor flexibility under schedule‐driven conditions of the lump‐sum engineering. In case after case, we saw that the engineering firm was unwilling to accelerate because they were working lump‐sum and were seeking to maximize profits. Lump‐sum engineering tends to experience more slip than reimbursable engineering and not respond well to any attempt to increase speed. This should not be a surprise. Engineering tends to slip because the engineer does not have readily available the engineering disciplines needed in the right order. On a reimbursable, he can hire from the street to fill gaps. On lump‐sum engineering, that is a recipe to lose money unless the fee formula is altered, which we discuss in Chapter 8.

Why So Much Reimbursable Construction?

Outside EPC‐LS contracts, only about 40 percent of projects in the process industries use lump‐sum contracts for construction. Straight reimbursable (fixed‐fee) and T&M together are more common despite generating inferior results. The amount of reimbursable and T&M construction goes up as projects get larger. Fewer than a third of projects more than $200 million have predominantly lump‐sum construction.

Some owners tell us that the construction companies resist lump‐sum construction, and some tell us they resist unit rates as well. But that is not really my experience in talking to construction firms. A friend of mine was CEO of a first‐rate construction company. He was adamant that lump‐sum construction was better for his firm because it kept them sharp and focused. “Reimbursable makes you sloppy.” I suspect what is actually going on is the construction firms resist lump‐sum with owners who don't understand construction management and with engineers that will not sequence their work to ensure that design and materials are available when needed.

When constructors work on a reimbursable or T&M basis rather than lump‐sum or unit rates, the owner is taking responsibility for risk associated with craft labor productivity. That violates a basic principle of contracting: when a risk is assigned to a party who does not control the risk, the risk goes unmanaged. Owners do not have the skills needed to control labor productivity. Therefore, they need to ensure the project is set up properly in front‐end loading and that the detailed engineering will support transfer of that risk to those who do.

Summary

The contracting strategies that we have reviewed in Chapters 3 and 4 are the standard approaches for industrial projects. Each strategy is appropriate in some circumstances, depending on the project, the strength of the owner, and the contractor market. Most industrial owners are able to use only one or two of the standard strategies effectively, and most often those are the EPC strategies. The reluctance of owners to employ the split strategies costs industrial owners massive amounts of money. Developing the capability needed to employ split strategies on a wide variety of projects would be a very profitable investment.

Many owners, however, are not satisfied that the standard approaches produce the best possible outcomes and look to other strategies to deliver better results. We discuss a number of those less common strategies in the next two chapters.

Notes

- 1 Corruption is possible under any contract form. The issue is not really one of compensation scheme but whether a fair competition was held in which all qualified contractors are given an opportunity. In jurisdictions in which EPC‐LS is required, it is also common to allow selection only on the basis of price offered. That creates another constraint on EPC‐LS bidding competitions and may be even more important than the strategy itself.

- 2 Depending on the way the contract is written and the choice of jurisdiction, important but deeply hidden FEED defects may come back to the owner despite the limitation period. Fundamental technology and Basic Data errors, for example, are difficult to transfer to the EPC if the technology decisions were all made by the owner.

- 3 Even if the owner does not “steer” the contract to the FEED EPC, that contractor has significant advantages anyway. If FEED contractors even suspect that they will be permitted to bid, they will look to hide cost in scope that is actually unnecessary and can be removed later. Sometimes soils information will be presented in ways that suggest the soil conditions are less favorable than they actually are. There are a large number of ways to at least modestly inflate scope, and a modest inflation is all that may be necessary to win the competition unfairly. When FEED contractors are allowed to bid in an EPC‐LS competition, they actually win more than 50 percent of the time—far more often than we would expect by chance.

- 4 Four bidders is optimal for EPC‐LS competitions as it results in the lowest cost project. More than four competitors is actually associated with higher cost rather than lower. That may seem counterintuitive, but it actually makes sense. As the number of bidders goes above four, the chances increase of receiving an exceptionally low bid, a bid separated from all others by 15 percent or more. In those cases, that low bid is often accepted even though it is implausible. Those projects usually go quite poorly. When too many contractors are invited to bid, the interest of the best contractors often declines because they are aware of the incompetent low bid problem. Unfortunately, owners are much more likely to invite three contractors to bid rather than four for EPC‐LS work. See Arkadii Lebedinskii, Bidding Duration Study, Independent Project Analysis, 2020.

- 5 Lebedinskii, op. cit.

- 6 See Edward Merrow, Kenneth Phillips, and Christopher Myers, Understanding Cost Growth and Performance Shortfalls in Pioneer Process Plants, The RAND Corporation, 1981.

- 7 For a discussion of shaping issues and their effects on projects, see Edward Merrow, Industrial Megaprojects, 2011, John Wiley & Sons, Chapters 4 and 5, pp. 53–122.

- 8 New technology was actually most prevalent in the Re/Re form at 11 percent of projects.

- 9 The frequency of schedule‐driven projects in GMPs is a result of the popularity of the form among pharmaceutical companies. Pharma companies often have “schedule‐driven” as their default project strategy, while other industrial‐sector companies rarely do. GMP will be discussed in Chapter 6.

- 10 There should have been an exit strategy for the owner with alternative contractors already explored. That off‐ramp should have been planned as a risk mitigation step, but in reality it is rarely done.

- 11 I will discuss the importance of prequalification for EPCM and other contractors in Chapter 7.

- 12 Direct hire of construction labor is when the EPC contractor hires individual craft laborers to execute most construction activities except so‐called specialty contracts—scaffolding, heavy lift, etc.—which are generally subcontracted in all cases.

- 13 EPCM is on average (without controlling any other factor) 6.5 percent more expensive than EPC‐LS. The result is very robust statistically: Pr.|t|<.005. The reader needs to be clear that 6.5 percent is a lot of money; for the average, my project in our sample, the premium is more than $30 million, and it only gets larger as a percentage with project size. If we control for the completeness of front‐end loading, the premium paid for EPCM over EPC‐LS increases to 9.4 percent on average. The typical EPCM is actually better prepared at FID than EPC lump‐sum projects. With that said, remember that EPC‐LS is often not an available alternative when EPCM is selected. But other strategies discussed later in this chapter are.

- 14 Time from start of scope development through to the end of production startup.

- 15 Time from FID to mechanical completion of facilities.

- 16 Although it is present for GMP contracts as well.

- 17 Do not forget to include access to all such information in the terms and conditions of the contract. There can be no ambiguity about the owner's right to the reimbursable cost information and the cost estimate they have paid for. If the contractor pushes back during negotiation, drop them and move to your second choice, which of course you will have maintained as an option as a matter of good practice.

- 18 We also find that modular construction had no effect on execution time regardless of any factors being controlled.

- 19 This does not mean that the master schedule developed in FEL is not critically important for a successful complex project; it decidedly is. However, the master schedule is for the purpose of understanding whether the project schedule is feasible, for deciding whether the peak labor requirements by craft are sustainable at the site, and for laying out the systems turnovers in the proper order to commission and start up the facilities.

- 20 The word bidding does not necessarily imply lump‐sum construction. Predominantly lump‐sum construction is used on about half of split form contracting projects, with reimbursable, T&M, and unit rates making up the remainder.

- 21 One might imagine that the integration of engineering and construction would not be a significant problem when using an EPC strategy. It is. Often the engineering and construction organizations of EPC firms are not well integrated. In most EPC firms, the engineers are in charge because the engineers make the sales. The constructors often do not have a strong position at the management tables of EPC firms and little way to force good integration.