CHAPTER 6

Collaborative and Relational Contracting Strategies

I define collaborative contracting as attempts to foster better working relationships between parties through the terms and conditions of the contract itself. Not included in this contracting strategy is the use of conventional incentive clauses. I define relational contracting as attempts by owners and contractors to establish long‐term working relationships without changing the contract terms and conditions—a conventional contracting form is employed.

There are two types of collaborative contracting: alliancing/integrated project delivery (IPD) and partnering alliances. One type of relational contracting is discussed that we call repeat supply chain. These three types of contracting strategies are associated with very different project outcomes.

IPD/Alliancing: In Search of Collaboration Through Contracting

Projects are joint products of owners and contractors. Collaboration—which means “to work together”—is important to project success. Collaboration at the working level is essential. Collaboration all the way up to the owner and contractor top managements is desirable. Some contracting approaches, in particular integrated project delivery/alliancing and partnering alliances, were developed with the goal of maximizing the potential for collaboration.

Integrated project delivery, which is usually called alliancing in the petroleum sector, is aimed at aligning the objectives of owner, contractors, licensors, and even major vendors by creating an incentive pool that will be shared if the project achieves designated targets.1 Sometimes, failure to meet those targets may create a “pain‐share” pool, in which overruns are distributed. Strictly speaking, IPD is an incentivized (usually) EPC (usually) reimbursable strategy. IPD seeks to go much further than the typical incentivized reimbursable to generate teamwork and align objectives with all players.

According to Phillip Barutha, who was the lead researcher for the Construction Industry Institute team on IPD, there are “six cardinal pillars” of IPD that are essential to the contract form.

- The integration of project participants early on, including those who do not normally join a project until halfway through the project cycle or later, e.g., constructors, fabricators, module, or facility transporters (in the case of modular on‐shore or offshore platforms), and installers

- Risk and reward sharing among all the members of the alliance, including the owner

- Collaborative, if not consensus, decision‐making

- Jointly developed and validated targets

- Liability waivers amongst the alliance members

- Multiparty agreements2

These key characteristics of IPD as a contract strategy are interesting in that a number of them conflict directly with the central elements of other contracting approaches. We will discuss these points after reviewing the performance of the strategy. We consider the multiparty incentive pooling arrangement as an essential feature of this contracting approach. We would not classify a project as IPD without it.

IPD has become somewhat popular in some regions, such as Australia, for publicly owned infrastructure project delivery. IPD has been tried from time to time in petroleum development projects in the U.K. North Sea and very occasionally for refining and chemicals projects in the United States and elsewhere. It has repeatedly been touted as the contracting form of the future, especially in the United Kingdom, but has never taken hold in industrial projects.3

There is a mistaken belief that IPD/alliancing has not been tested for industrial projects4 and is therefore something new. In fact, the approach has been tried on many industrial projects starting at least as long ago as 1994 with BP's Andrew Project. IPA has evaluated more than major 30 industrial projects using IPD/alliancing as the contracting methodology. Petroleum production, refining, petrochemicals, minerals processing, and industrial infrastructure projects are included in our IPD/alliancing set. The projects tend to be large with a median cost of more than $1 billion. The smallest project in this set is more than $250 million. All of the IPD projects we examined had multiparty agreements in place, the element that is most often missing from the “pillars” cited previously.

When looking at the history of IPD/alliancing since it was introduced nearly 30 years ago, it has caught on in some project sectors, but not in industrial projects where economic profit is the ultimate goal. IPD/alliancing has generally been used much more often in sectors and for projects in which cost‐competitiveness is not paramount, such as hospital design and construction in the United States. It has never caught on in industrial sectors as a mainstream contracting approach and I strongly suspect it never will. We have only one company in our database that has used IPD/alliancing more than twice; the modal number of uses is one. The basic reason is quite straightforward: IPD/alliancing has very few true “successes” when capital cost competitiveness is an important measure of success.

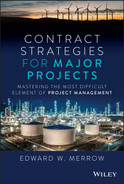

As shown in Figure 6.1, IPD/alliancing had the poorest outcomes of all contracting strategies in IPA's databases, even worse than convert to EPC‐LS. Of particular note is their lack of cost competitiveness with the average project at 126 percent of industry average. Cost growth was highly variable but averaged over 30 percent real.5 A number of projects underran their FID budgets (while usually being expensive), and a number were cost blow‐outs.

FIGURE 6.1 IPD/alliancing is expensive and slow.

Conceptually, IPD/alliancing makes sense. One of the biggest problems in project execution is the management of the interfaces between the many organizations involved. If only all organizations could be motivated via the incentive pool and good communication to cooperate more fully, many of the pain points and much of the friction might be avoided.

When IPD/alliancing is chosen, it is often accompanied by a great deal of owner effort to integrate with the contractors and suppliers. “One team, one voice, one outcome, one shared destiny” are typical of the slogans and sentiments that accompany the form. Team‐building sessions and the like are quite common. The use of the contracting form is often the subject of publicity around the project as well, especially if it is a large and prominent project. IPD requires a good deal of owner work in its implementation.

When owners used IPD/alliancing, they selected the strategy early in front‐end loading and formed the pool of contractors no later than FEED (FEL 3). The owners and contractors were very aware that they were trying something different, which might have led to a “Hawthorne effect” but judging from the results clearly did not.6 The owners put more thought and work into the contracting strategy for these projects than any other strategy I have seen. The owner personnel were often personally invested in making the strategy successful. This sometimes resulted in very intense denial when the failures of the projects were documented. There was even one project that was a complete disappointment including a large overrun, significant schedule slip, and very poor plant operability in which the owner PM and contractor leads wrote an effusive trade magazine article praising the contracting strategy used on the project while omitting the project results.7

Case Studies of One‐Off IPD/Alliances

To better understand the dynamics of integrated project delivery in industrial projects, I want to offer two case studies that are quite typical of two groups of IPD/alliancing projects: the first represents what was considered a successful application of the strategy, while the second represents what can only be described as very disappointing. Almost all IPD/alliancing projects in our dataset are represented in one of these two cases. I am disguising the projects as needed to protect confidentiality as well as the innocent and the guilty.

A Successful IPD/Alliance

This was an off‐shore petroleum development project in European waters. It was to increase production at an existing asset by tapping into some adjacent reserves that could not be reached from the original project. The project cost was just over $500 million, which included drilling, making it a modest‐sized project by offshore standards. The project incorporated no new technology, and the scopes were quite standard and familiar to all involved. As is typical of an offshore project, there were lots of players involved—several contractors, heavy lift company, major suppliers, and a field service firm. Eight companies in all signed the alliance agreement. Lots of players, of course, means lots of interfaces to manage.

The idea for forming an alliance to implement the project came from “lots of calls from contractors” to the business sponsor at the operating company encouraging an IPD form. The host government was also actively encouraging the strategy as well as a way of supporting EPC contractors. The contracting strategy was embraced by most (not all) of the project team but viewed with some suspicion by the nonoperating partners. As is usually the case, the operating partner's views prevailed.

The alliance agreement detailed a complex incentive structure that included a base fee as negotiated in individual contracts between the owner and contractor plus a variety of performance fees and pots of contingency money, some of which would be entirely kept by the contractor if not expended and some of which would add to the alliance incentive account to be shared among the members. There were provisions for “pain‐sharing,” but in most instances when pain would result, the owner stepped in with its contingency funds to bail out those situations. The incentive fees were in aggregate considerably larger than the base fees contained in the individual contracts.

Project Drivers

The project practices were generally as good as or better than the industry average. The objectives were clearly and fully defined; the team included all the needed disciplines, including operations and maintenance; roles and responsibilities were fully defined; and an active risk management program was in place. The front‐end loading was industry average. The drivers, taken as a whole, would lead us to expect a better‐than‐average project with fairly good cost and schedule performance. The FEL could and should have been better, but it was at least industry average.

The alliance members were encouraged (and incentivized) to bring cost‐savings ideas to the fore and did so, but the savings suggested were modest, which is not surprising considering the very conventional nature of the project.

Execution proceeded smoothly, especially considering that a significant number of major changes were required, in fact more than double the industry average.8 The alliance mostly operated as intended, but the lead owner operator was surprised at the amount of active intervention it had to provide, especially with regard to cost controls.

Project Results

Construction safety was very poor. Both DART and recordable injuries were double industry average. Interestingly, the safety provisions of the alliance contract were written in a way to make it extremely unlikely that the contractors would suffer any loss of incentive fees due to safety problems. Only a fatality or a single catastrophic event would cause any loss. Merely being double the industry average for injuries caused no loss of incentive.9

Costs underran by 12 percent, while cost competitiveness was very poor at 30 percent over industry average. That means that the starting authorization (FID) estimate was a whopping 40+ percent over a competitive number! This is the story of “successful” IPD projects: generous estimates, underruns, and poor competitiveness.

The schedule slipped by about seven months amounting to a 15 percent slip in the execution schedule. Like cost, the schedule was not aggressive at the start with a planned schedule competitiveness index of 1.10. Therefore, the project eroded some business value due to schedule but much less than the effect of the overspend. Startup experienced a few hiccups but nothing out of the ordinary.

So, was this a successful project? It would seem that success, like beauty, is often in the eye of the beholder. The team and the business sponsor considered the project a brilliant success and attributed that success to the alliance. I strongly suspect that some of the contractors (not all) did as well. The contractor who arguably performed worst by a considerable margin scored a profit in excess of 15 percent of their costs. The contractor who arguably performed best took home less than 1 percent of the base cost and probably lost money overall. This underscores the difficulty of devising an incentive payment scheme ex ante that will faithfully represent performance ex post. In this case, the relationships among alliance partners remained functional throughout the project. However, that was surely facilitated by the generous budget for the project.

An Unsuccessful Alliance

The second case is a $300 million commodity chemicals project using an innovative technology route for a standard product. The alliance was formed in front‐end loading and included the technology developer and two engineering contractors, the constructor, and the owner. The constructor was able to make input into the constructability of the design and design and procurement sequencing. A pooled gain/pain‐share incentive was established for the alliance members.

The primary impetus for the alliance arrangement was the hope that it would facilitate communication and cooperation, especially between the technology developer and the engineering contractors. In particular, it was expected that the licensor and engineering contractors would work seamlessly and that the constructor's input would mitigate the effects of late engineering input should that occur. The owner was experienced with IPD, and the alliance had good top management support.

Drivers

The drivers were very strong for this project: a fully integrated and fully staffed owner team and best practical front‐end loading. However, unlike our prior case study, the targets for this project were tight. Cost was set at 98 percent of industry average, and schedule was 96 percent. Planned operability was very high at 100 percent of nameplate in the first year. The gain/pain share was aimed at both cost and schedule, but schedule was the key driver with $75,000 per day gainshare available for earlier than planned mechanical completion.

Execution

The engineering was a nightmare. The technology developer and engineering firms fought constantly. Their systems were not compatible, and their attitudes were not either. They fought over roles and ownership of improvements. The alliance contract provided no practical conflict resolution. Engineering was quite late, which extended procurement and resulted in poor labor productivity for the constructor in the field. The constructor was in a zero‐profit situation before even starting his work.

Project Outcomes

Cost grew by 10 percent, which was really pretty good, all things considered, but this wiped out all cost‐related incentives. Schedule, however, slipped 17 percent. The project was from a capital cost and schedule perspective not too bad, but no incentives were paid, and the contractors made little or no money, depending on whether they had hidden profit in their multiplier. The real problem was startup and operability. The plant produced only about 30 percent of nameplate in the first six months and then finally came to steady‐state at about 65 percent of nameplate in the second year. The poor operability was clearly a product of the poor working relationships among the technology developer and engineers and wiped out all business value for the venture. This was a negative returns project.

Why did this project fail? It failed because the owner expected the contractual form to induce the contractors to do what the contractors really did not want to do: trust each other and cooperate and freely share information. They had fundamentally misaligned objectives, and the incentives in the contract did not change that. More importantly, the alliance form did not provide the sort of clearly delineated roles and responsibilities that would have assisted in conflict resolution. Instead, shared risks became nobody's risk. The constructor, of course, being last in line bore the brunt.

The Meaning of “Success” in IPD

A single handful of IPD/alliancing projects in our database were considered successes by the owners. Those projects look remarkably similar. The projects either underran or came in close to their FID budgets while being uncompetitive in cost by 20 to 30 percent. Their schedule results varied, but the cost underruns overrode any disappointments associated with schedule. The tendency to conflate cost underruns with success in projects, which we discussed in Chapter 3, is a near‐universal phenomenon.

In sectors where cost‐competitiveness is rarely measured, a cost‐ineffective contracting strategy can thrive if it is routinely associated with not overrunning the budget. When projects go badly, it is quite possible that everybody involved loses money—owner and contractor alike—regardless of the compensation scheme. But when a project goes smoothly, underruns its budget, but is very expensive, somebody got rich, and it isn't the owner.

Collaborative contracting is often premised on everything going well. It envisions projects without significant surprises and without substantial conflict. Perhaps the hope is that the contracting form can alter the project reality.

There are several things wrong with this premise. First, contracting is always a second‐order driver of outcomes at best. Project realities are unaltered by contracting form except in cases where contracting makes a project worse. Contracts have little ability to alter poor fundamentals. This is not pessimistic thinking. This is just reality.

Second, collaborative contracting tends to submerge conflict under a haze of good feeling. But it is still there. Contractor management does not tell their project team “Oh, don't worry about us making a profit on this one.” So rather than clearly marking, understanding, and managing the principal‐agent fault lines, potential conflicts are not seen until they have erupted and caused damage to the project. For example, in one large chemical project using IPD/alliancing, despite lots of team building, alliance sessions, and discussions, it did not emerge until FID that one joint venture partner in the project would not approve any project with any form of reimbursable construction. The constructor had already been brought on to the project and signed a contract on a reimbursable compensation basis. The project was delayed three months by the need to renegotiate the contract to lump‐sum for construction. We can all agree that conflict is bad for projects, but unseen, and therefore unmanageable, conflict is much worse.

Third, IPD seems premised on the notion that there is an enormous amount of money to be saved via better collaboration among all players. Good collaboration, however achieved, will certainly save some time and money, but it cannot possibly create a breakthrough in construction productivity. Only massive substitution of capital for labor can do that, and collaboration doesn't touch that issue.

Fourth, one‐off collaborative contracting approaches always suffer from a lack of time. When I have asked contractor and owner engagement leaders for partnering alliance relationships (discussed later in the chapter) how long it takes for the organizations to understand each other, no one has ever said less than two years, and most have said three. Yet with one‐off IPD we expect a number of organizations to learn how to work smoothly with each other in a matter of weeks or a couple of months, not years. Workable levels of collaboration between owners and contractors can develop quickly if the conditions are there. But deep collaboration takes a good deal of time to develop. Because they are multiproject and multiyear arrangements, partnering alliances and repeat supply chain strategies discussed later in this chapter do not suffer from this time constraint defect.

Finally, the most mistaken aspect of one‐off IPD/alliancing is the belief that collaboration requires contractual help. Unless the organizations have worked to create barriers, most owner and contractor personnel expect to work collaboratively to complete a project. There are important prerequisites—clear objectives, clear delineation of roles and responsibilities, competence, and mutual respect. Those things are both necessary and sufficient for a collaborative work environment to develop. Things beyond those conditions are window dressing or distractions.

The Six Pillars in Context of Results

Now let us return to the six “pillars” introduced at the start of this chapter and discuss each in light of the results of industrial IPD. The first pillar is the integration of all key project players early on. This is a compelling goal: managing the early involvement of the contractors and important service providers who start their work late in the project cycle. The most prominent of these are the constructors. For the typical process facility, more than 60 percent of the cycle time has expired before a constructor starts work. If brought into the project shortly before their work is to start, none of their requirements and preferences have been heard. None of their ideas for how to improve construction have been incorporated into the engineering and procurement efforts for the project.

One rationale for the EPC forms of contracting is that the constructors are embedded in the principal contractor and therefore will be fully represented in the front end. It is remarkable, however, how often that does not happen in EPC‐R contracting. Construction professionals in many EPCs complain that their inputs are not really welcomed by the engineers in their firm and that the engineers, as the point of sales, call all the shots. In EPCM contracting, as we discussed in Chapter 4, the construction management component is often not fully defined up front in FEED where it will count the most.

Bringing the constructors, fabricators, heavy‐lift companies, and other providers on the project contractually during front‐end loading creates a host of problems and sharply limits the contract options available. It renders Re/LS, one of the most effective of all strategies, essentially impossible to implement. I believe the best practical solution to this problem is to bring potential constructors and others in to review the project toward the end of FEED as part of the prequalification process. Let them fully inspect and critique the project execution plan, engineering sequencing and packaging, and the procurement approach. That will mitigate the problem of not hearing those who join late, provided that the owner and engineering firm are listening. This does not entail or require an IPD form but will accomplish a key goal.

The second pillar of IPD is risk and reward sharing. I believe this element of IPD is highly problematic. There is an old saying in contracts: “Shared risk is your risk.” As I will discuss in more detail in Chapter 9, contracting is all about risk assignment. One of the key purposes of a contract is to clearly articulate which risk belongs to which party. Fans of IPD often argue that other contracting strategies constitute “risk shedding” by owners. It is surely true that some owners in some circumstances seek to dump as much risk onto their contractors as they possibly can. As we have noted, that doesn't really work, but some do try it. But most contracting strategies seek to assign risks according to who best controls a risk, not simply shed risk. And a great many industrial projects today are done under no‐risk‐to‐contractor contractual approaches. EPCM is the most popular of all industrial contracting strategies, and it is usually a low‐risk or no‐risk to contractor form. It hardly represents a “risk‐shedding” strategy.

The third pillar of IPD is “collaborative decision‐making.” If collaborative is taken to mean that owners fully and carefully listen to the input of their contractors, then I am a firm supporter. If it means what it suggests, that decisions are made jointly, it is borderline insane for complex projects. The asset being created is being funded by and will be used for as much as a generation by the owner, not the contractors. Capital projects need strong owners.10 Listening well is a key attribute of project leadership, but sharing decision‐making is an attribute of weak leaders.11

The fourth pillar of IPD is jointly developed targets for cost and schedule. Target‐setting is one of the most difficult things to do well in capital projects.12 Setting aggressive targets without a clear path to achieve them is a fool's game. Setting soft targets means you will achieve soft results. Jointly developing and validating targets is common enough on incentivized contract arrangements, but it doesn't make the principal‐agent problem go away.

The fifth pillar of IPD is liability waivers for all alliance members. The waiver of liability means that no member of the alliance has legal recourse against another for damages they may suffer in the execution of the project. I have not seen a blanket waiver of liability in alliance agreements and have not seen a waiver litigated for gross negligence.13 What is peculiar about the waiver provision is that the alliance members normally sign individual contracts with the owner and those contracts contain conventional liability frameworks. If a large failed IPD project did end up in litigation, I would expect a bonanza for the legal profession. Baratha finds that the liability waiver provision is the least agreed upon of the IPD pillars.14 It is easy to understand why.

Finally, to have a true alliance, there needs to be an agreement among all the participants to define and memorialize the intended relationships among all the players. The agreement always calls for collaboration and a “no blame” culture. The multiparty agreement acts as a kind of “no fault insurance” arrangement. But the problem with this is that many of the parties, especially the owner, want actual insurance in place. Insurance, however, is fault‐based, and if no one is at fault, then how does it work?

In our experience with IPD/alliancing, getting the multiparty agreement signed by all intended participants is often difficult. Securing agreement from all about the risk‐sharing formula is most problematic. The usual multiparty agreement is not signed and final until execution is well under way. It is particularly difficult to get those who will start their work late to agree to a situation in which they could start their work in a loss position on the project. Often, specialty contractors refuse to join the alliance at all, arguing that their profits should not depend on the performance of others. As one of my colleagues put it, “Alliancing is a bit like those dreaded graduate school class projects where everyone receives the same grade even though the work performance is never uniform.”

It is my conclusion that although well intentioned, IPD/alliancing has a very small niche in industrial project contracting and probably no place in complex industrial projects. In its attempt to eliminate the principal‐agent problem in contracting, it merely submerges it. When it does resurface, the contract offers no assistance. If an owner is not cost‐conscious, IPD may appear to be workable, but only at the expense of shareholders somewhere. There is no free lunch. Virtually all industrial owners are in fact cost‐conscious.

Partnering/Long‐Term Alliances

Partnering refers to long‐term, multiproject relationships between an owner and a contractor. The relationships are often dubbed “alliances,” but the form is quite different from one‐off IPD/alliancing. This model of contracting involves signing a multiyear multiproject contract between an owner and a contractor, usually an EPC. The typical contract length is five years and is renewable by mutual consent. The contractor is usually involved in front‐end loading and carries on to do detailed engineering and construction. Some agreements guarantee the contractor a minimum level of work each year, but most do not.

The partnering form became popular for major industrial projects during the 1990s in the United States. At that time, there was an over‐supply of EPC contractors in the market, and most contractors were very hungry for work. When the industrial projects market started to accelerate after 2003, the approach was largely abandoned except for site‐based small project systems where it continues to be a staple. Our sample of major industrial projects from this century has no examples of partnering form projects.

When the contracting approach was in use during the 1990s, IPA conducted a series of studies trying to understand whether it was a superior form.15 Some examples were indeed spectacular performers. One large chemical company executed all of its projects in the United States and Europe with three partner EPC contractors in long‐term partner alliances. The owner maintained a strong engineering and projects organization that followed strong practices. Five‐year contracts were executed with the three partner contractors, and projects were allocated among the three based on expertise. A certain amount of competitive tension was maintained in the three‐contractor arrangement.

We also found that for every partnership like the previous one, there was one that produced poor project results. For example, another major chemical company had a long‐term relationship with a single contractor that produced projects that averaged more than 30 percent more than industry average cost while producing persistent underruns! That systematic over‐capitalization contributed to the demise of the company. The partnerships were a study in extreme contrasts; some brilliant project results were obtained, and some very poor project results were produced.

The differences in the two sets were clear. The strong partnerships had strong owner project organizations with a very strong focus on front‐end loading excellence. The partnerships producing poor project results had been used as a vehicle for downsizing and outsourcing engineering and project skills by the owners. It left the owners easy prey for contractors who overestimated projects, brought in underruns, and pocketed out‐sized profits. Second, the strong partnerships had very active relationship management on both sides. This was relational contracting at its best. Both owner and contractor understood that maintaining the partnership was going to take significant work. Third, the owners in successful partnerships always stayed in touch with the market. They would bid the occasional project out on an EPC‐LS basis to see if the partner EPCs were producing competitive results. When more than one partner contractor was involved, they would introduce a measure of competition between them, giving more work at the margin to the contractor performing better. Finally, the owner in successful partnering relationships had reasonably stable project workloads and modest expectations. In the unsuccessful cases, there were sometimes grossly misaligned objectives: the owner was looking for the contractor to smooth the peaks and valleys in their project portfolio while the contractor was looking for steady work. What could go wrong?

The period from about 1984 to 2003 was a period of relatively low work in the process industries around the world. The petroleum industry was in a period of low and very low prices, and the minerals industry was mostly in an overcapacity situation. Chemicals growth was mostly in line with global economic growth, but margins were being eroded by globalization of the industry. This was also a period of overcapacity in the engineering and construction industry because the rapid growth of the 1970s and early 1980s had spawned a much larger EPC industry that was then devastated by the collapse of oil prices in 1984. This made the period quite a benign one for owners (and a miserable one for contractors) and facilitated the functionality of partnership arrangements.

When the demand for engineering and construction services suddenly accelerated in 2004, the EPC industry was at low‐ebb and had significantly consolidated. The partnerships were largely abandoned as the shortage of EPC services took hold. If project markets in a region are in an extended low period and surplus EPC capacity exists, partnership arrangements are clearly workable. But all of the lessons from the 1990's experience still pertain: strong partnerships need strong owners and strong relationship management to work along with some mechanism to maintain contact with the market.

Repeat Supply Chain Contracting

We end our discussion of unusual contracting strategies with repeat supply chain (RSC) contracting. All of our RSC projects are drawn from petroleum production projects, but there is no obvious reason why equivalent results would not occur in other industrial sectors. Our databases contain more than 70 RSC projects in 17 separate series that range from 2 to 9 projects. The average capital cost of the projects is just under $2 billion, although they range downward to about $100 million. Virtually all of the projects were contracted as lump‐sums.

A repeat supply chain occurs when the same set of suppliers—engineering firm, substructure vendor/yard, topsides fabricator, and systems integrator—is used for sequential projects with an owner on a sole source basis. What differentiates RSC from partnering contracting is that each project is governed by a separate contract with no guarantee of future work. RSC contracting is always accompanied by some degree of standardization. In some respects, standardization is a necessary condition because the contractors and suppliers must be capable of performing over a series of projects, so the projects cannot be too dissimilar. A large amount of heterogeneity of project scopes would make that all but impossible. The degree of standardization varied from series to series, and none of the series of projects were characterized by highly (greater than 80 percent) standardized scope.

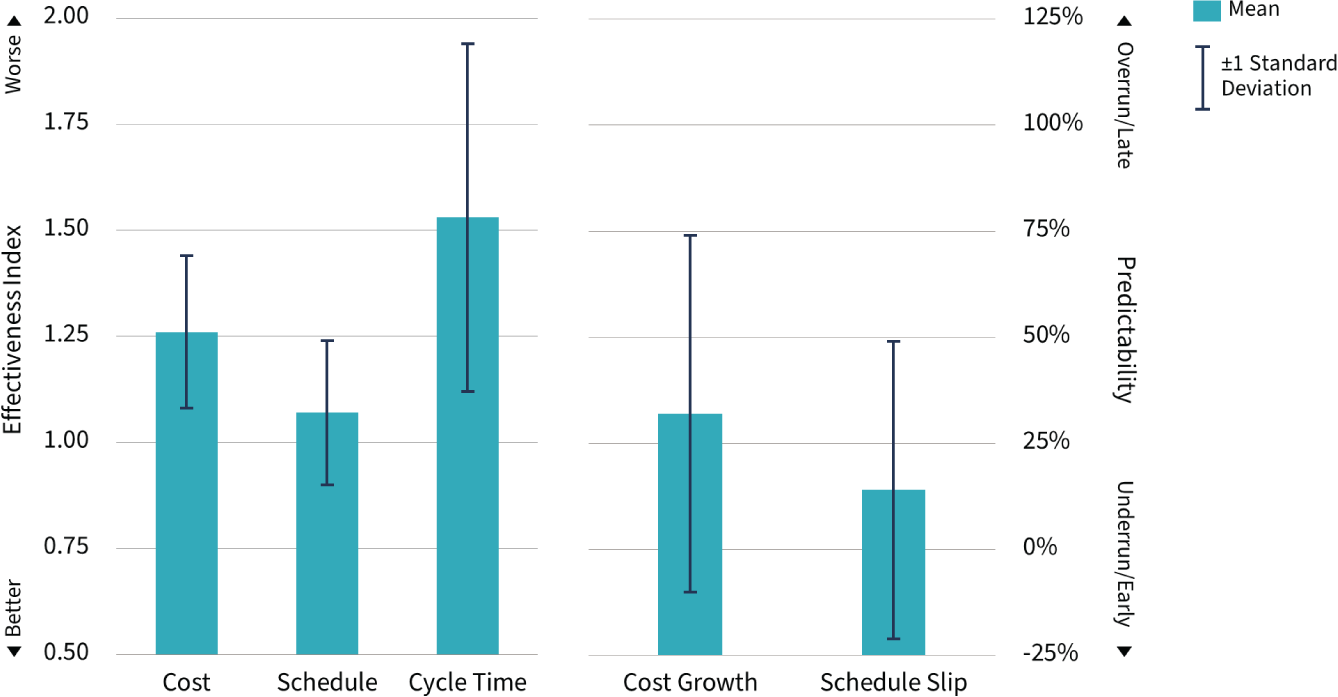

As shown in Figure 6.2, RSC contracting produces excellent value for owners—the best overall results of any particular contracting form.16 In addition to excellent cost, schedule, and cycle time results, RSC contracted projects experienced the fewest operability problem in the first year after startup of any contracting approach.17 But in keeping with the principle that there is never a free lunch, RSC contracting is quite difficult to manage and may be limited in potential application.

FIGURE 6.2 Repeat supply chains provide the best value overall.

Repeat supply chains usually started as a matter of serendipity rather than design. An owner would develop a project in some region and select via competitive bidding a set of contractors and service providers to perform the work. After the project went unusually well, the owner decided that rather than competitively bidding the next project in the same geography, he would invite the contractors and other suppliers on the first project to join the next project on a sole source basis, agree on a cost estimate and schedule, and execute the second project. There is no “all‐party agreement” in this form. This process is repeated until there are no more projects for the owner or one of the parties loses interest. As soon as the contractors and other suppliers accept that this will continue, the relationships and contracts become self‐enforcing. Exploiting the situation for monetary gain or doing demonstrably poor work would mean that the next project would go to a competitor.

The best known RSC in the petroleum industry was the series of deep water spar production platform projects led by Don Vardeman, first at Oryx Petroleum and then carried to Kerr‐McGee and finally Anadarko through acquisition. As Vardeman explained, the key to the contracting strategy was the careful maintenance of the relationships over time.18 Not every project went perfectly, and not every contractor performance was exemplary, but the relationships were managed by frank discussions of performance, give and take, and constant learning. There were never any formal guarantees, but there was the guarantee that if the suppliers were faithful to the relationship by doing solid work, they would always be rewarded with the next job. The average platform in that series of megaprojects cost 75 percent of industry average, which is astounding performance.

The benefits of RSC are obvious. As the set of suppliers work together on sequential projects, the management of the interfaces becomes progressively easier. The repeat nature of the work means that low cost could be maintained, while profitability for the contractors and suppliers improved because the work was being done more efficiently. The self‐enforcing nature of the relationships means that senior leadership is aligned on both the buyer and seller sides.19

All of the RSC series that we have seen were confined to a particular region of the world. In principle, it may be possible to run an RSC across regions, but we have not seen it done. In some companies, RSC contracting generates strenuous objections from the procurement organization or the legal department due to the sole source nature of the strategy. Some engineering organizations and business functions also object to the high degree of standardization that is often necessary to make RSC contracting work. And, of course, in some jurisdictions such sole source contracting is illegal because open bidding competitions are required for projects.

What I find most interesting is that RSC contracting appears to generate all of the advantages sought by IPD/alliancing—excellent collaboration, early involvement of all parties, better management of interfaces, and better alignment of incentives. But RSC contracting does this without gimmick and without asking the contracts to generate the collaboration, which clearly does not work. The contracts for the RSC projects were standard fixed‐price contracts. They were also mostly irrelevant, which is the best contract of all.

The Effects of Scale on the Unusual Contracting Forms

One of the most important attributes of a contracting strategy is how its effectiveness changes with project size and complexity. As we noted in Chapter 4, EPC reimbursable and EPCM scale quite poorly. As owners lose line‐of‐sight control, the forms become progressively more expensive and slow. EPC lump‐sum degrades with size, but not as severely as the two reimbursable forms. The split forms Re/LS and Re/Re do not degrade at all with increased size and complexity.

The unusual forms differ in how they respond to size and complexity:

- Duty spec contracts remain relatively constant with respect to size as long as standard solutions are available at the size and complexity sought. There may be some tendency for operability to degrade with complexity.

- Design competitions are unaffected by size and complexity. Some of the most successful complex megaprojects resulted from well‐run design competitions.

- Convert to lump‐sum are also unaffected by size and complexity, but that is not a good thing! They tend to be very expensive for owners at all sizes.

- Because GMPs are usually on the smaller size, there is not enough variation to understand how they scale.

- IPD/alliancing does not scale well. IPD megaprojects were not only disproportionately failures; IPD/alliancing appears to be a causal factor in increasing their chances to fail even in a group of projects that do not tend to do very well.20 Smaller IPDs tend to be expensive but are more likely to go smoothly than megaproject alliances. IPD is a complex contractual form that often does a poor job assigning risk. That is a poor match for projects with a large number of participants and built‐in problems for good risk assignment.

- Partnering arrangements were rarely used with projects over about $250 million. Owners that had partnering contractors tended to go to market outside the partnerships for the big projects and contract them on a one‐off basis. I believe the reason for this is that a very large project could upset the partnership arrangements by overwhelming the staffing capability of the partner contractor within the relationship. In most partner arrangements, the contractor staffing for the partner owner was quite stable as personnel would be assigned long term. For these reasons we can't know how the form would scale.

- Repeat supply chain scales very well as a contracting form. We cannot tell how scale would affect any single supply chain series because the projects tended to be of fairly uniform size. RSCs that started large remained large, and those that started with small projects tended to remain small. The RSC contracting dataset, however, had a disproportionate number of megaprojects. Provided that sufficient standardization can be sustained, RSC is a capable contracting strategy for megaprojects.

Notes

- 1 In this discussion, I am only referring to the use of IPD in a “one‐off” project situation. When collaborative strategies are used with contractors on a long‐term, multiproject basis, those are considered “partnering alliance” situations, not IPD.

- 2 Philip James Barutha, Integrated Project Delivery for Industrial Projects, Dissertation, Iowa State University, Department of Civil Engineering, 2018. A very similar set of criteria were developed much earlier by the European Construction Institute study of Alliancing published in 2000. See Bob Scott, et al., Partnering in Europe, Thomas Telford Publishing, London, 2000.

- 3 B. Scott, op. cit. 2000.

- 4 See “Integrated Project Delivery for Industrial Projects,” Construction Industry Institute Research Team 341, Final Report 341, July 2019.

- 5 The term real is used because the effects of any escalation and foreign currency changes have been removed.

- 6 The Hawthorne effect derives from a series of industrial “scientific management” experiments conducted by Elton Mayo and Associates at the Hawthorne, New York, facility of the General Electric Company in the early 20th century. Because the company personnel involved in the experiments knew that they were being watched and measured, their performance was far better than expected.

- 7 One common characteristic of IPD/alliances is that the final alliance contracts were often significantly delayed.

- 8 We define a major change as any change (design or scope) that changes the expected total costs by more than one‐half of 1 percent or the schedule by more than one month. In this case, any change of more than $3.5 million would qualify as a major change.

- 9 This is unfortunately rather common in incentivized contracts. As we will discuss in Chapter 7, safety gets a great deal of play in that process and then is often forgotten when it comes to actual selection of contractors.

- 10 See Graham M. Winch and Roine Leiringer (2016). “Owner Project Capabilities for Infrastructure Development: A Review and Development of the ‘Strong Owner’ Concept.” International Journal of Project Management, 34(2), 271–281.

- 11 For a discussion of project leadership skills including the importance of listening, see E.W. Merrow and Neeraj Nandurdikar, Leading Complex Projects, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

- 12 See Paul H. Barshop, Capital Projects, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- 13 In most engineering and construction contracts, caps on liability can be lifted if gross negligence or fraud is proven.

- 14 Baratha, op. cit., p. 43.

- 15 E.W. Merrow, “Partnering Alliances and Project Outcomes,” Industry Benchmarking Consortium Annual Meeting, 1996; and see E.W. Merrow, “Contracting Strategy,” Industry Benchmarking Consortium Annual Meeting Proceedings, March 2000.

- 16 There are two sources of cost efficiency at work in RSC contracting: standardization and the contracting strategy. Sorting out the contribution of each discretely is difficult because standardization of industrial projects is almost always accompanied by a contracting approach that is in effect RSC.

- 17 E.W. Merrow and J.A. Walker, “The Efficacy of Unusual Contracting Approaches in Petroleum Production Projects,” Proceedings of the Upstream Industry Benchmarking Consortium Annual Meeting, November 2019.

- 18 See Edward W. Merrow and Neeraj S. Nandurdikar, op. cit., pp. 130 ff.

- 19 Of note, the RSCs did not show learning curves in which each project was more cost competitive than the one before. I believe there are two reasons for this. First, the RSCs were only started because the first project was cost effective, which had the effect of lowering the Y‐intercept on the learning curve. Second, the suppliers could improve their profitability, which may well have been on the low side for the initial projects, by being more efficient in the subsequent projects.

- 20 See E. Merrow, Industrial Megaprojects, op. cit. p. 260.