Chapter 9

Margin analysis: structure

If financial analysis were a puppet, company strategy would be pulling its strings

An analysis of a company's margins is the first step in any financial analysis. It is a key stage because a company that does not manage to sell its products or services for more than the corresponding production costs is clearly doomed to fail. But, as we shall see, positive margins are not sufficient on their own to create value or to escape bankruptcy.

Net income is what is left after all the revenues and charges shown on the income statement have been taken into account. Readers will not therefore be very surprised to learn that we will not spend too much time on analysing net income as such. A company's performance depends primarily on its operating performance, which explains why recurring operating profit (or EBIT) is the focus of analysts' attention. Financial and non-recurrent items are regarded as being almost “inevitable” or “automatic” and are thus less interesting, particularly when it comes to forecasting a company's future prospects.

The first step in margin analysis is to examine the accounting practices used by the company to draw up its income statement. We dealt with this subject in Chapter 8 and shall not restate it here, except to stress how important it is. Given the emphasis placed by analysts on studying operating profit, there is a big temptation for companies to present an attractive recurring operating profit by transferring operating charges to financial or non-recurring items.

The next stage involves a trend analysis based on an examination of the revenues and charges that determined the company's operating performance. This is useful only insofar as it sheds light on the past to help predict the future. Therefore, it is based on historical data and should cover several financial years. Naturally, this exercise is based on the assumption that the company's business activities have not altered significantly during the period under consideration.

The main aim here is to calculate the rate of change in the main sources of revenue and the main costs, to examine their respective trends and thus to account for the relative change in the margins posted by the company over the period.

The main potential pitfall in this exercise is adopting a purely descriptive approach, without much or any analytical input, e.g. statements such as “personnel cost increased by 10%, rising from 100 to 110 …”.

Margin trends are a reflection of a company's:

- strategic position, which may be stronger or weaker depending on the scissors effect; and

- risk profile, which may be stronger or weaker depending on the breakeven effect that we will examine in Chapter 10.

All too often the strategic aspects are neglected, with the lion's share of the study being devoted to ratios and no assessment being made of what these figures tell us about a company's strategic position.

As we saw in Chapter 8, analysing a company's operating profit involves assessing what these figures tell us about its strategic position, which directly influences the size of its margins and its profitability:

- a company lacking any strategic power will, sooner or later, post a poor, if not negative, operating performance;

- a company with strategic power will be more profitable than the other companies in its business sector.

In our income statement analysis, our approach therefore needs to be far more qualitative than quantitative.

Section 9.1 How operating profit is formed

By-nature format income statements (raw material purchases, personnel cost, etc.), which predominate in Continental Europe, provide a more in-depth analysis than the by-?function format developed in the Anglo-Saxon tradition of accounting (cost of sales, selling and marketing costs, research and development costs, etc.). Granted, analysts only have to page through the notes to the accounts for the more detailed information they need to get to grips with. In most cases, they will be able to work back towards EBITDA1 by using the depreciation and amortisation data that must be included in the notes or in the cash flow statement.

1/ Sales

Sales trends are an essential factor in all financial analysis and company assessments. Companies for which business activities are expanding rapidly, stagnating, growing slowly, turning lower or depressed will encounter different problems. Sales growth forms the cornerstone for all financial analysis. Sales growth needs to be analysed in terms of volume (quantities sold) and price trends, organic and external growth (i.e. acquisition driven).

Before sales volumes can be analysed, external growth needs to be separated from the company's organic growth, so that like can be compared with like. This means analysing the company's performance (in terms of its volumes and prices) on a comparable-?structure basis and then assessing additions to and withdrawals from the scope of consolidation. In practice, most groups publish pro forma accounts in the notes to their accounts showing the income statements for the relevant and previous periods based on the same scope of consolidation and using the same consolidation methods.

If a company is experiencing very brisk growth, analysts will need to look closely at the growth in operating costs and the cash needs generated by this growth.

A company experiencing a period of stagnation will have to scale down its operating costs and financial requirements. As we shall see later in this chapter, production factors do not have the same flexibility profile when sales are growing as when sales are declining.

Where a company sells a single product, volume growth can easily be calculated as the difference between the overall increase in sales and the selling price of its product. Where it sells a variety of different products or services, analysts face a trickier task. In such circumstances, they have the option of either working along the same lines by studying the company's main products or calculating an average price increase, based on which the average growth in volumes can be estimated.

An analysis of price increases provides valuable insight into the extent to which overall growth in sales is attributable to inflation. The analysis can be carried out by comparing trends in the company's prices with those in the general price index for its sector of activity. Account also needs to be taken of currency fluctuations and changes in the product mix, which may sometimes significantly affect sales, especially in consolidated accounts.

In turn, this process helps to shed light on the company's strategy, i.e.:

- whether its prices have increased through efforts to sell higher-value-added products;

- whether prices have been hiked owing to a lack of control on administrative overheads, which will gradually erode sales performance;

- whether the company has lowered its prices in a bid to pass on efficiency gains to customers and thus to strengthen its market position;

- etc.

Key points and indicators:

- The rate of growth in sales is the key indicator that needs to be analysed.

- It should be broken down into volume and price trends, as well as into product and regional trends.

- These different rates of growth should then be compared with those for the market at large and (general and sectoral) price indices. Currency effects should be taken into account.

- The impact of changes in the scope of consolidation on sales needs to be studied.

2/ Production

Sales represent what the company has been able to sell to its customers. Production represents what the company has produced during the year and is computed as follows:

| Production sold, i.e. sales | |

| + | Changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress at cost price |

| + | Production for own use, reflecting the work performed by the company for itself and carried at cost |

| = | Production |

First and foremost, production provides a way of establishing a relationship between the materials used during a given period and the corresponding sales generated. As a result, it is particularly important where the company carries high levels of inventories or work in progress. Unfortunately, production is not entirely consistent insofar as it lumps together:

- production sold (sales), shown at the selling price;

- changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress and production for own use, stated at cost price.

Consequently, production is primarily an accounting concept that depends on the methods used to value the company's inventories of finished goods and work in progress.

A faster rate of growth in production than in sales may be the result of serious problems:

- overproduction, which the company will have to absorb in the following year by curbing its activities, bringing additional costs;

- overstatement of inventories' value, which will gradually reduce the margins posted by the company in future periods.

Production for own use does not constitute a problem unless its size seems relatively large. From a tax standpoint, it is good practice to maximise the amount of capital expenditure that can be expensed, in which case production for own use is kept to a minimum. An unusually high amount may conceal problems and an effort by management to boost book profit superficially.

Key points and indicators:

- The growth rate in production and the production/sales ratio are the two key indicators.

- They naturally require an analysis of production volumes and inventory valuation methods.

3/ Gross margin

Gross margin is the difference between production and the cost of raw materials used.

| Production | |

| − | Purchase of raw materials |

| + | Change in inventories of raw materials |

| = | Gross margin |

It is useful in industrial sectors where it is a crucial indicator and helps to shed light on a company's strategy.

This is another arena in which price and volume effects are at work, but it is almost impossible to separate them out because of the variety of items involved. At this general level, it is very hard to calculate productivity ratios for raw materials. Consequently, analysts may have to make do with a comparison between the growth rate in cost of sales and that in net sales (for by-function income statements), or the growth rate of raw materials and that in production (by-nature income statements). A sustained difference between these figures may be attributable to changes in the products manufactured by the company or improvements (deterioration) in the production process.

Conversely, internal analysts may be able to calculate productivity ratios based on actual raw material costs used in the operating cycle since they have access to the company's management accounts.

Key points and indicators:

- How changes in the gross margin are explained between price and volume effects

4/ Gross trading profit

Gross trading profit is the difference between the selling price of goods for sale and their purchase cost.

| Sale of goods | |

| − | Purchase of goods for sale |

| + | Change in inventories of goods for sale |

| = | Gross trading profit |

It is useful only in the retail, wholesale and trading sectors, where it is a crucial indicator and helps to shed light on a company's strategy. It is usually more stable than its components (i.e. sales and the cost of goods for sale sold).

5/ Value added

This represents the value added by the company to goods and services purchased from third parties through its activities. It is equivalent to the sum of gross trading profit and gross margin used minus other goods and services purchased from third parties.

It may thus be calculated as follows for by-nature income statements:

| Gross trading profit | |

| + | Gross margin |

| − | Other operating costs purchased from third parties |

| = | Value added |

Other operating costs comprise outsourcing costs, property or equipment rental charges, the cost of raw materials and supplies that cannot be held in inventory (i.e. water, energy, small items of equipment, maintenance-related items, administrative supplies, etc.), maintenance and repair work, insurance premiums, studies and research costs, fees payable to intermediaries and professional costs, advertising costs, transportation charges, travel costs, the cost of meetings and receptions, postal charges and bank charges (not interest on bank loans, which is booked under interest expense).

For by-function income statements, value added may be calculated as follows:

| Operating profit (EBIT) | |

| + | Depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets |

| + | Personnel costs |

| + | Tax other than corporate income tax |

| = | Value added |

At company level, value added is of interest only insofar as it provides valuable insight regarding the degree of a company's integration within its sector. It is not uncommon for an analyst to say that average value added in sector X stands at A, as opposed to B in sector Y.

Besides that, we do not regard the concept of value added as being very useful. In our view, it is not very helpful to make a distinction between what a company adds to a product or service internally and what it buys in from the outside. This is because all decisions of a company are tailored to the various markets in which it operates, such as the markets for labour, raw materials, capital and capital goods, to cite but a few. Against this backdrop, a company formulates a specific value-creation strategy, i.e. a way of differentiating its offering from that of its rivals in order to generate a revenue stream.

This is what really matters – not the internal/external distinction.

In addition, value added is only useful where a market-based relationship exists between the company and its suppliers in the broad sense of the term, e.g. suppliers of raw materials, capital providers and suppliers of labour. In the food sector, food processing companies usually establish special relationships with the farming industry. As a result, a company with a workforce of 1000 may actually keep 10 000 farmers in work. This raises the issue of what such a company's real value added is.

Where a company has established special contractual ties with its supplier base, the concept of value added loses its meaning.

Value added is a useful concept only where a market-based relationship exists between a company and its suppliers.

6/ Personnel cost

This is a very important item because it is often high in relative terms. Although personnel cost is theoretically a variable cost, it actually represents a genuinely fixed-cost item from a short-term perspective.

A financial analysis should focus both on volume and price effects (measured by the ![]() ratio) as well as the employee productivity ratio, which is measured by the following ratios:

ratio) as well as the employee productivity ratio, which is measured by the following ratios: ![]() ,

,![]() . Since external analysts are unable to make more accurate calculations, they have to make a rough approximation of the actual situation. In general, productivity gains are limited and are thinly spread across most income statement items, making them hard to isolate.

. Since external analysts are unable to make more accurate calculations, they have to make a rough approximation of the actual situation. In general, productivity gains are limited and are thinly spread across most income statement items, making them hard to isolate.

Analysts should not neglect the inertia of personnel cost, as regards either increases or decreases in the headcount. If 100 additional staff members are hired throughout the year, this means that only 50% of their salary costs will appear in the first year, with the full amount showing up in the following period. The same applies if employees are laid off.

Key points and indicators:

Personnel cost should be analysed in terms of:

- productivity – sales/average headcount, value added/average headcount and production/average headcount;

- cost control – personnel cost/average headcount;

- growth.

7/ earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation

As we saw in Chapter 3, EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) is a key concept in the analysis of income statements. The concepts we have just examined, i.e. value added and production, have more to do with macroeconomics, whereas EBITDA firmly belongs to the field of microeconomics.

We cannot stress strongly enough the importance of EBITDA in income statement analysis.

EBITDA represents the difference between operating revenues and cash operating charges. Consequently, it is computed as follows:

| Operating profit (EBIT) | |

| + | Depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets |

| = | EBITDA |

Alternatively, for by-nature income statements, EBITDA can be computed as follows:

| Value added | |

| − | Taxes other than on income |

| − | Personnel cost and payroll charges |

| − | Impairment losses on current assets and additions to provisions |

| + | Other operating revenues |

| + | Depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets |

| − | Other operating costs |

| = | EBITDA |

Other operating costs comprise charges that are not used up as part of the production process and include items such as redundancy payments, recurring restructuring charges, payments relating to patents, licences, concessions, representation agreements and directors' fees. Other operating revenues include payments received in respect of patents, licences, concessions, representation agreements, directors' fees, operating subsidies received.

Impairment losses on current assets include impairment losses related to receivables (doubtful receivables), inventories, work in progress and various other receivables related to the current or previous periods. Additions to provisions primarily include provisions for retirement benefit costs, litigation, major repairs and deferred costs, statutory leave, redundancy or pre-redundancy payments, early retirement, future under-activity and relocation, provided that they relate to the company's normal business activities. In fact, these provisions represent losses for the company and should be deducted from its EBITDA.

Personnel expense and payroll charges also include employee incentive payments, stock options and profit-sharing.

Since it is unaffected by non-cash charges – i.e. depreciation, amortisation, impairment charges and provisions, which may leave analysts rather blindsided – trends in the EBITDA/sales ratio, commonly known as the EBITDA margin, form a central part of a financial analysis. All the points we have dealt with so far in this section should enable a financial analyst to explain why a group's EBITDA margin expanded or contracted by x points between one period and the next. The EBITDA margin change can be attributable to an overrun on production costs, to personnel cost, to the price effect on sales or to a combination of all these factors.

Our experience tells us that competitive pressures are making it increasingly hard for companies to keep their EBITDA margin moving in the right direction!

The following table shows trends in the EBITDA margins posted by various sectors in Europe over the 2000– 2015 period (2014 and 2015 are brokers' consensus estimates).

| Sector | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014e | 2015e |

| Aerospace & Defence | 9% | 10% | 11% | 10% | 11% | 12% | 11% | 9% |

| Automotive | 9% | 8% | 10% | 10% | 11% | 9% | 6% | 11% |

| Building Materials | 17% | 17% | 16% | 17% | 17% | 15% | 14% | 14% |

| Capital Goods | 10% | 9% | 11% | 11% | 14% | 13% | 12% | 14% |

| Consumer Goods | 18% | 14% | 15% | 14% | 15% | 14% | 13% | 14% |

| Food Retail | 6% | 6% | 6% | 6% | 7% | 6% | 6% | 7% |

| IT Services | 9% | 12% | 9% | 9% | 9% | 10% | 9% | 9% |

| Luxury Goods | 15% | 16% | 19% | 19% | 20% | 20% | 20% | 23% |

| Media | 8% | 16% | 21% | 22% | 22% | 22% | 21% | 22% |

| Mining | 17% | 29% | 41% | 42% | 41% | 39% | 34% | 44% |

| Oil & Gas | 19% | 19% | 20% | 18% | 18% | 18% | 17% | |

| Pharmaceuticals | 21% | 26% | 30% | 32% | 32% | 33% | 35% | 36% |

| Steel | 11% | 16% | 17% | 16% | 16% | 8% | 10% | |

| Telecom Operators | 40% | 32% | 35% | 34% | 33% | 33% | 34% | 33% |

| Utilities | 48% | 16% | 23% | 22% | 22% | 20% | 22% | 21% |

Source: Exane BNP Paribas

It clearly shows, among other things, the tiny but stable EBITDA margin of food retailers, and the very high EBITDA margin of telecom groups which was impacted by the Internet bubble blowout in 2000– 2002. The highest margins are for the mining industry, which needs heavy investment, thus requiring high margins in order to get sufficient returns.

8/ Operating profit or EBIT

Now we come to the operating profit (EBIT), an indicator whose stock is still at the top. Analysts usually refer to the operating profit/sales ratio as the operating margin, trends in which must also be explained.

Operating profit is EBITDA minus non-cash operating costs. It may thus be calculated as follows:

| EBITDA | |

| + − | Depreciation and amortisation |

| + | Write-backs of depreciation and amortisation |

| = | Operating profit or EBIT |

Impairment losses on fixed assets relate to operating assets (brands, purchased goodwill, etc.) and are normally included with depreciation and amortisation by accountants. We beg to differ as impairment losses are normally non-recurring items and as such should be excluded by the analyst from the operating profit and relegated to the bottom of the income statement.

As we saw in Chapter 3, the by-function format directly reaches operating profit without passing through EBITDA:

| Sales | |

| − | Cost of sales |

| − | Selling, general and administrative costs |

| − | Research and development costs |

| +/− | Other operating income and costs |

| = | Operating profit (or EBIT) |

The emphasis placed by analysts on operating performance has led many companies to attempt to boost their operating profit artificially by excluding charges that should logically be included. These charges are usually to be found on the separate “Other income and costs” line, below operating profit, and are, of course, normally negative.

Other companies publish an operating profit figure and a separate EBIT figure, presented as being more significant than operating profit. Naturally, it is always higher, too.

For instance, we have seen foreign currency losses of a debt-free company,2 recurring provisions for length-of-service awards and environmental liabilities, costs related to under-activity and anticipated losses on contracts excluded from operating profit. In other cases, capital gains on asset disposals have been included in recurring EBIT.

We believe it is vital for readers to avoid preconceptions and to analyse precisely what is included and what is not included in operating profit. In our opinion, the broader the operating profit definition, the better!

The following table shows trends in the operating margin posted by various sectors over the 2000– 2015 period.

The reader may notice, for example, how cyclical the steel sector is in stark contrast to the food retail sector.

| Sector | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014e | 2015e |

| Aerospace & Defence | 4% | 6% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 9% | 7% | 6% |

| Automotive | 3% | 4% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 4% | 1% | 6% |

| Building Materials | 11% | 11% | 11% | 12% | 12% | 11% | 8% | 8% |

| Capital Goods | 6% | 6% | 7% | 8% | 11% | 10% | 9% | 10% |

| Consumer Goods | 13% | 11% | 12% | 11% | 12% | 11% | 9% | 10% |

| Food Retail | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% |

| IT Services | 6% | 10% | 6% | 6% | 7% | 8% | 7% | 7% |

| Luxury Goods | 13% | 13% | 15% | 16% | 17% | 17% | 16% | 19% |

| Media | 5% | 11% | 18% | 18% | 18% | 17% | 16% | 17% |

| Mining | 12% | 21% | 34% | 35% | 35% | 32% | 25% | 37% |

| Oil & Gas | 13% | 15% | 15% | 14% | 14% | 11% | 12% | |

| Pharmaceuticals | 16% | 20% | 25% | 27% | 28% | 28% | 30% | 31% |

| Steel | 6% | 12% | 13% | 13% | 12% | 2% | 6% | |

| Telecom Operators | 18% | 15% | 20% | 18% | 17% | 17% | 18% | 17% |

| Utilities | 31% | 9% | 15% | 15% | 15% | 13% | 14% | 13% |

Source: Exane BNP Paribas

Section 9.2 How operating profit is allocated

EBIT is divided up among the company's providers of funds: financial earnings for the lenders, net income for the shareholders, and corporation tax for the government, which although it does not provide funds, creates and maintains infrastructure and a favourable environment; without forgetting non-recurrent items.

1/ Net financial expense/income

It may seem strange to talk about net financial income for an industrial or service company whose activities are not primarily geared towards generating financial income. Since finance is merely supposed to be a form of financing a company's operating assets, financial items should normally show a negative balance, and this is generally the case. That said, some companies, particularly large groups generating substantial negative working capital (like big retailers, for instance), have financial aspirations and generate net financial income, to which their financial income makes a significant contribution.

Net financial expense thus equals financial expense minus financial income. Where financial income is greater than financial expense, we naturally refer to it as net financial income.

Financial income includes:

- income from securities and from loans recorded as long-term investments (fixed assets). This covers all income received from investments other than participating interests, i.e. dividends and interest on loans;

- other interests and related income, i.e. income from commercial and other loans, income from marketable securities, other financial income;

- write-backs of certain provisions and charges transferred, i.e. write-backs of provisions, of impairment losses on financial items and, lastly, write-backs of financial charges transferred;

- foreign exchange gains on debt;

- net income on the disposal of marketable securities, i.e. capital gains.

Financial expense includes:

- interest and related charges;

- foreign exchange losses on debt;

- net expense on the disposal of marketable securities, i.e. capital losses on the disposal of marketable securities;

- amortisation of bond redemption premiums;

- additions to provisions for financial liabilities and charges and impairment losses on investments.

Where a company uses sophisticated financial liabilities and treasury management techniques, we advise readers to analyse its net financial income/expense carefully.

Net financial expense is not directly related to the operating cycle, but instead reflects the size of the company's debt burden and the level of interest rates. There is no volume or price effect to be seen at this level. Chapter 12, which is devoted to the issue of how companies are financed, covers the analysis of net financial expense in much greater detail.

Profit before tax is the difference between operating profit and financial expense net of financial income.

2/ Non-recurring items

Depending on accounting principles, firms are allowed to include more or fewer items in the exceptional/extraordinary items line. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has decided to include extraordinary and exceptional items within operating without identifying them as such. Nevertheless, the real need for such a distinction has led a large number of companies reporting in IFRS to present a “recurring operating profit” (or similar term) before the operating profit line.

Non-recurring items should be defined on a case-by-case basis by the analyst.

One of the main puzzles for the financial analyst is to identify whether an extraordinary or exceptional item can be described as recurrent or non-recurrent. If it is recurrent, it will occur again and again in the future. If it is not recurrent, it is simply a one-off item.

Without any doubt, extraordinary items and results from discontinued operations are non-recurrent items.

Exceptional items are much more tricky to analyse. In large groups, closure of plants, provisions for restructuring, etc. tend to happen every year in different divisions or countries and should consequently be treated as recurring items. In some sectors, exceptional items are an intrinsic part of the business. A car rental company renews its fleet of cars every nine months and regularly registers capital gains. Exceptional items should then be analysed as recurrent items and as such be included in the operating profit. For smaller companies, exceptional items tend to be one-off items and as such should be seen as non-recurrent items.

It makes no sense to assess the current level of non-recurring items from the perspective of the company's profitability or to predict their future trends. Analysts should limit themselves to understanding their origin and why, for example, the company needed to write down the goodwill.

3/ Income tax

The corporate income tax line can be difficult to analyse owing to the effects of deferred taxation, the impact of foreign subsidiaries and tax-loss carryforwards. Analysts usually calculate the group's effective tax rate (i.e. corporate income tax divided by profit before tax), which they monitor over time to assess how well the company has managed its tax affairs. A weak tax rate must be explained. It may be due to the use of tax losses carried forward or to aggressive tax optimization schemes which are not risk-free especially when countries are running high levels of debts and/or deficits.

In the notes to the accounts, there is a table that explains the reconciliation between the theoretical tax rate on companies and the tax rate effectively paid by the company or the group (it is called “tax proof”).

4/ Goodwill impairment, income from associates, minority interests

Regarding goodwill impairment, the main questions should be: Where does this goodwill come from and why was it depreciated?

Depending on its size, the share of net profits (losses) of associates3 deserves special attention. Where these profits or losses account for a significant part of net income, either they should be separated out into operating, financial and non-recurring items to provide greater insight into the contribution made by the equity-accounted associates, or a separate financial analysis should be carried out of the relevant associate.

Minority interests4 are always an interesting subject and beg the following questions: Where do they come from? Which subsidiaries do they relate to? Do the minority investors finance losses or do they grab a large share of the profits? An analysis of minority interests often proves to be a useful way of working out which subsidiary(ies) generate(s) the group's profits.

Section 9.3 Standard income statements (individual and consolidated accounts)

The following tables show two model income statements. The first has been adapted to the needs of non-consolidated (individual) company accounts and is based on the by-nature format. The second is based on the by-function format as it is used in the Indesit group's consolidated accounts.

BY-NATURE INCOME STATEMENT – INDIVIDUAL COMPANY ACCOUNTS

| Periods | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| NET SALES | |||

| + Changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress + Production for own use |

|||

| = PRODUCTION | |||

| − Raw materials used − Cost of goods for resale sold = GROSS MARGIN or GROSS TRADING PROFIT − Other purchases and external charges |

|||

| = VALUE ADDED | |||

| − Personnel cost (incl. employee profit-sharing andincentives) − Taxes other than on net income + Operating subsidies − Change in operating provisions5 + Other operating income and cost |

|||

| = EBITDA | |||

| − Depreciation and amortisation | |||

| = EBIT (OPERATING PROFIT) (A) | |||

| Financial expense − Financial income − Net capital gains/(losses) on the disposal of marketablesecurities + Change in financial provisions |

|||

| = NET FINANCIAL EXPENSE (B) (A)−(B)= PROFIT BEFORE TAX ANDNON-RECURRING ITEMS |

|||

| +/− Non-recurring items including impairment losses on fixed assets − Corporate income tax = NET INCOME (net profit) |

Table BY-FUNCTION INCOME STATEMENT – CONSOLIDATED ACCOUNTS

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | ||||||

| € m | % | € m | % | € m | % | € m | % | € m | % | |

| NET SALES | 2613 | −17% | 2879 | +10% | 3155 | +10% | 2894 | −8% | 2671 | −8% |

| − Cost of sales | 1939 | 2044 | 2378 | 2180 | 2050 | |||||

| = GROSS MARGIN | 26.4% | 674 | 835 | 29.0% | 777 | 24.6% | 714 | 24.8% | 621 | |

| − Selling and marketing costs | 408 | 483 | 503 | 454 | 433 | |||||

| − General and administrative costs | 97 | 124 | 114 | 105 | 104 | |||||

| ± Other operating income and expense | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| + Income from associates | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| = RECURRING OPERATING PROFIT | 169 | 6.5% | 228 | 7.9% | 160 | 4.9% | 155 | 5.4% | 84 | 3.1% |

| ± Non-recurring items | (50) | (44) | (19) | (19) | (16) | |||||

| = OPERATING PROFIT (EBIT) | 119 | 4.6% | 184 | 6.4% | 141 | 4.3% | 136 | 4.7% | 68 | 2.6% |

| − Financial expense | 53 | 36 | 58 | 37 | 53 | |||||

| + Financial income | 2 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 2 | |||||

| = PROFIT BEFORE TAX | 68 | 2.6% | 150 | 5.2% | 95 | 2.9% | 102 | 3.5% | 17 | 0.6% |

| − Income tax | 33 | 60 | 39 | 40 | 14 | |||||

| − Minority interests | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| = NET PROFIT ATTRIBUTABLE TO SHAREHOLDERS | 34 | 1.3% | 90 | 3.1% | 56 | 1.7% | 62 | 2.1% | 3 | 0.0% |

Section 9.4 Financial assessment

1/ The scissors effect

The scissors effect is, first and foremost, the product of a simple phenomenon.

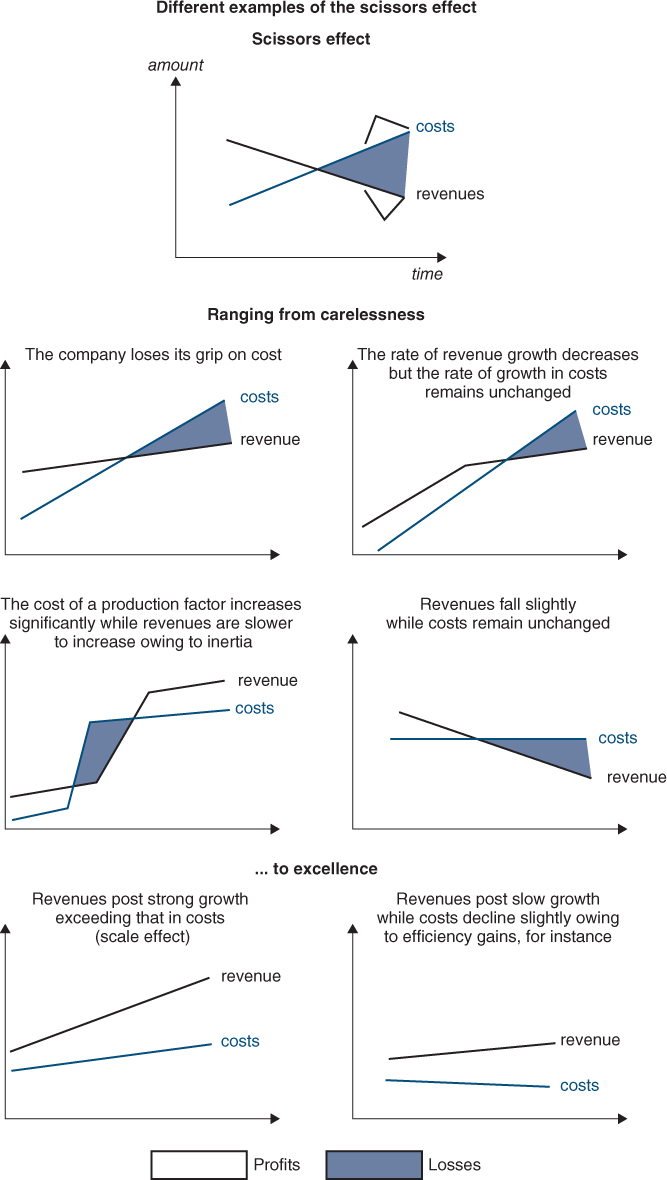

The scissors effect is what takes place when revenues and costs move in diverging directions. It accounts for trends in profits and margins.

If revenues are growing by 5% p.a. and certain costs are growing at a faster rate, earnings naturally decrease. If this trend continues, earnings will decline further each year and ultimately the company will sink into the red. This is what is known as the scissors effect.

Whether or not a scissors effect is identified matters little. What really counts is establishing the causes of the phenomenon. A scissors effect may occur for all kinds of reasons (regulatory developments, intense competition, mismanagement in a sector, etc.) that reflect the higher or lower quality of the company's strategic position in its market. If it has a strong position, it will be able to pass on any increase in its costs to its customers by raising its selling prices and thus gradually widening its margins.

Where it reduces profits, the scissors effect may be attributable to:

- a statutory freeze on selling prices, making it impossible to pass on the rising cost of production factors;

- psychological reluctance to put up prices. During the 1970s, the impact of higher interest rates was very slow to be reflected in selling prices in certain debt-laden sectors;

- poor cost control, e.g. where a company does not have a tight grip on its cost base and may not be able to pass rising costs on in full to its selling prices. As a result, the company no longer grows, but its cost base continues to expand.

The impact of trends in the cost of production factors is especially important because these factors represent a key component of the cost price of products. In such cases, analysts have to try to estimate the likely impact of a delayed adjustment in prices. This depends primarily on how the company and its rivals behave and on their relative strength within the marketplace.

But the scissors effect may also work to the company's benefit, as shown by the last two charts in the following figure.

2/ Pitfalls

A company's accounts are littered with potential pitfalls, which must be sidestepped to avoid errors of interpretation during an analysis. The main types of potential traps are as follows.

(a) The stability principle (which prevents any simplistic reasoning)

This principle holds that a company's earnings are much more stable than we would expect. Net income is frequently a modest amount that remains when charges are offset against revenues. Net income represents an equilibrium that is not necessarily upset by external factors. Let's consider, for instance, a supermarket chain where the net income is roughly equal to the net financial income. It would be a mistake to say that if interest rates decline, the company's earnings will be wiped out. The key issue here is whether the company will be able to slightly raise its prices to offset the impact of lower interest rates, without eroding its competitiveness. It will probably be able to do so if all its rivals are in the same boat. But the company may be doomed to fail if more efficient distribution channels exist.

The situation is very similar for champagne houses. A poor harvest drives up the cost of grapes, and pushes up the selling price of champagne. Here the key issues are when prices should be increased in view of the competition from sparkling wines, the likely emergence of an alternative product at some point in the future and consumers' ability to make do without champagne if it is too expensive.

It is important not to repeat the common mistake of establishing a direct link between two parameters and explaining one by trends in the other.

A company's margins also depend to a great extent on those of its rivals. The purpose of financial analysis is to understand why they are above or below those of its rivals.

That said, there are limits to the stability principle.

(b) Regulatory changes

These are controls imposed on a company by an authority (usually the government) that generally restricts the “natural” direction in which the company is moving. Examples include an aggressive devaluation, the introduction of a shorter working week or measures to reduce the opening hours of shops.

(c) External factors

Like regulatory changes, these are imposed on the company. That said, they are more common and are specific to the company's sector of activity, e.g. pressures in a market, arrival (or sudden reawakening) of a very powerful competitor or changes to a collective bargaining agreement.

(d) Pre-emptive action

Pre-emptive action is where a company immediately reflects expectations of an increase in the cost of a production factor by charging higher selling prices. This occurs in the champagne sector where the build-up of pressure in the raw materials market following a poor grape harvest very soon leads to an increase in prices per bottle. Such action is taken even though it will be another two or three years before the champagne comes onto the marketplace.

Pre-emptive action is particularly rapid where no alternative products exist in the short to medium term and competition in the sector is not very intense. It leads to gains or losses on inventories that can be established by valuing them only at their replacement cost.

(e) Inertia effects

Inertia effects are much more common than those we have just described, and they work in the opposite direction. Owing to inertia, a company may struggle to pass on fluctuations in the cost of its production factors by upping its selling prices. For instance, in a sector that is as competitive and has such low barriers to entry as the road haulage business, there is usually a delay before an increase in diesel fuel prices is passed on to ?customers in the form of higher shipping charges.

(f) Inflation effects

Inflation distorts company earnings because it acts as an incentive for overinvestment and overproduction, particularly when it is high (e.g. during the 1970s and the early 1980s). A company that plans to expand the capacity of a plant four years in the future should decide to build it immediately; it will then save 30–40% of its cost in nominal terms, giving it a competitive advantage in terms of accounting costs. Building up excess inventories is another temptation in high-inflation environments because time increases the value of inventories, thereby offsetting the financial expense involved in carrying them and giving rise to inflation gains in the accounts.

Inflation gives rise to a whole series of similar temptations for artificial gains, and any players opting for a more cautious approach during such periods of madness may find themselves steamrollered out of existence. By refusing to build up their inventories to an excessively high level and missing out on inflation gains, they are unable to pass on a portion of them to consumers, as their competitors do. Consequently, during periods of inflation:

- depreciation and amortisation are in most cases insufficient to cover the replacement cost of an investment, the price of which has risen;

- inventories yield especially large nominal inflation gains where they are slow-moving.

Deflation leads to the opposite results.

(g) Capital expenditure and restructuring

It is fairly common for major investments (e.g. the construction of a new plant) to depress operating performance and even lead to operating losses during the first few years after they enter service.

For instance, the construction of a new plant generally leads to:

- additional general and administrative costs such as R&D and launch costs, professional fees, etc;

- financial costs that are not matched by any corresponding operating revenue until the investment comes on stream (this is a common phenomenon in the hotel sector given the length of the payback periods on investments). In certain cases, they may be capitalised and added to the cost of fixed assets but this is even more dangerous;

- additional personnel cost deriving from the early recruitment of line staff and managers, who have to be in place by the time the new plant enters service;

- lower productivity owing both to the time it takes to get the new plant and equipment running and the inexperience of staff at the new production facilities.

As a result of these factors, some of the investment spending finds its way onto the income statement, which is thus weighed down considerably by the implications of the investment programme.

Conversely, a company may deliberately decide to pursue a policy of underinvestment to enhance its bottom line (so they can be sold at an inflated price) and to maximise the profitability of investments it carried out some time ago. But this type of strategy of maximising margins jeopardises its scope for value creation in the future (it will not create any new product, it will not train sufficient staff to prepare for changes in its business, etc.).

Section 9.5 Case study: Indesit

In 2009 sales in Eastern European countries and Russia dropped by 46% (!) due in particular to retailers' financial difficulties and devaluations. In 2010, activity picked up, led by emerging countries and, in particular, Russia (catch-up effect). This was only a short-term phenomenon as sales dropped again by 8% in 2012 and again by 8% in 2013. There are three main explanations: the strength of the euro which depresses sales made in Eastern European currencies when translated into euros; deflation in the white goods industry (the price of a fridge went down by 31% in Italy between 2008 and 2013) and a loss in market share due to excellent performances from LG and Samsung accounting now for roughly 5% each against 2% five years ago.

Despite such volatility in sales, Indesit had succeeded in maintaining a decent operating margin until 2013 thanks to the transfer of part of the production to, and sourcing from, low-cost countries (e.g. Poland). But the operating margin was divided by two in 2013 as Indesit suffered from having too many production facilities in Western Europe where the hourly labour cost is around € 24 versus € 5– 6 in Poland, Turkey or Russia where new entrants on the European market have set up their plants. Even if labour accounts for around 10% of sales and productivity is better in Western Europe, this has an impact on margins.

Summary

The summary of this chapter can be downloaded from www.vernimmen.com.

The first step in any financial analysis is to analyse a company's margins. This is absolutely vital because a company that fails to sell its products or services to its customers above their cost is doomed.

An analysis of margins and their level relative to those of a company's competitors reveals a good deal about the strength of a company's strategic position in its sector.

Operating profit, which reflects the profits generated by the operating cycle, is a central figure in income statement analysis. First of all, we look at how the figure is formed based on the following factors:

- sales, which are broken down to show the rate of growth in volumes and prices, with trends being compared with growth rates in the market or the sector;

- production, which leads to an examination of the level of unsold products and the accounting method used to value inventories, with overproduction possibly heralding a serious crisis;

- raw materials used and other external charges, which need to be broken down into their main components (raw materials, transportation, distribution costs, advertising, etc.) and analysed in terms of their quantities and costs;

- personnel cost, which can be used to assess the workforce's productivity (sales/average headcount, value-added/average headcount) and the company's grip on costs (personnel cost/average headcount);

- depreciation and amortisation, which reflect the company's investment policy.

Further down the income statement, operating profit is allocated as follows:

- net financial expense, which reflects the company's financial policy. Heavy financial expense is not sufficient to account for a company's problems, it merely indicates that its profitability is not sufficient to cover the risks it has taken;

- non-recurring items (extraordinary items, some exceptional items and results from discontinued operations) and the items specific to consolidated accounts (income or losses from associates, minority interests, impairment losses on fixed assets).

- corporate income tax.

Diverging trends in revenues and charges produce a scissors effect, which may be attributable to changes in the market in which the company operates, e.g. economic rents, monopolies, regulatory changes, pre-emptive action, inertia. Identifying the cause of the scissors effect provides valuable insight into the economic forces at work and the strength of the company's strategic position in its sector. We are able to understand why the company generates a profit, and get clues about its future prospects.

Questions

1/ If you had to analyse the non-consolidated accounts of a holding company of several industrial participations, which profit level would you focus on? What are the important items on the income statement? Are the consolidated accounts of this holding company interesting?

2/ The industrial group HEEMS shows a net result, 80% of which is from extraordinary income. State your views.

3/ The industrial group VAN DAM shows a net result, 80% of which is from its financial income. State your views.

4/ Why can a direct link not be drawn between an increase in production costs and the corresponding drop in profits?

5/ What steps can be taken to help offset the impact of a negative scissors effect?

6/ Of the following companies, which would you define as making “a margin between the end market and an upstream market”?

- temporary employment agency;

- storage company (warehouse);

- slaughterhouse;

- furniture manufacturer;

- supermarket.

7/ What does the stability of a company's net profits depend on?

8/ Van Poucke NV has positive EBITDA and growth, but negative operating profit. State your views.

9/ What is your view of a company which has seen a huge increase in sales due to a significant drop in prices and a strong volume effect?

10/ Why analyse minority interests on the consolidated income statement?

11/ Why break down contributions made by associate companies into operating, financial and non-recurring items?

12/ In a growing company, would you expect margins to grow or to decrease?

More questions are waiting for you at www.vernimmen.com.

Exercises

1/ Identify the sector to which each of the following types of company belongs: electricity producer, supermarket, temporary employment agency, specialised retailer, construction and public infrastructure.

| Company | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Sales | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Production | 100 | 100 | 104 | 99 | 0 |

| Trading profit | 23.0 | 24.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Raw materials used | 0 | 0 | } 46.6 | 23.6 | 0 |

| Other external charges | 7.8 | 7.0 | 46.9 | 14.1 | |

| Personnel cost | 9.3 | 11.7 | 21.5 | 24.1 | 88.2 |

| EBITDA | 6.8 | 6.7 | 28.1 | 3.7 | 4.6 |

| Depreciation and amortisation | 2.6 | 0.9 | 14.4 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Operating income | 4.2 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

2/ Identify the sector to which each of the following types of company belongs: cement, luxury products, travel agency, stationery, telecom equipment.

| Company | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Sales | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Cost of sales | 35.9 | 84.0 | 67.7 | 44.3 | 52.2 |

| Marketing and selling costs | 37.0 | 4.4 | 14.0 | 23.1 | 21.8 |

| Administrative costs | 11.1 | 10.0 | 6.6 | 10.7 | 9.3 |

| R&D costs | 0 | 0 | 20.1 | 6.6 | 2.1 |

| Operating income | 16.0 | 1.6 | −8.3 | 15.3 | 14.6 |

Answers

Questions

1/ Focus on the financial result. Administrative costs, corporate income tax. No, as consolidated accounts will only reflect the cumulated financial situation of very diverse activities.

2/ It is important to understand the nature of this extraordinary income as, by definition, it is not likely to be recurring.

3/ It is important to understand the nature of this financial income: is it due to excess cash or to withdrawal of provisions?

4/ Because of the very complex issues at work which will require further study.

5/ Be flexible: outsource, bring in temporary staff.

6/ Temporary employment agency: margin between the direct employment market and the temporary employment market. Warehouse: fixed costs although margins are linked to volumes of business. Slaughterhouses: margin between downstream and upstream. Manufacturer of furniture: margin between raw material, the wood and the sales price. Supermarkets: fixed costs although margins are linked to volumes of business.

7/ On the cyclical nature of sales, the flexibility of the company (fixed/variable cost split), and the margin in absolute value.

8/ Analyse the investments and amortisation policy, along with impairment losses on fixed assets.

9/ What is the impact on EBITDA?

10/ In order to find out which of the group's entities is making profits.

11/ To obtain a clearer view of the entirety of the income statement, especially operating income.

12/ Margins should increase in theory as the company should enjoy a scale effect. It is often the reverse as, in growing markets, gain of market share is made at the expense of margins by cutting prices.

Exercises

1/ Electricity production: 3 (large amount booked under depreciation and amortisation); supermarkets: 1 (lowest trading profits, it is a low margins business); temporary employment agency: 5 (high personnel cost); specialised retail: 2 (highest trading profits); building and public infrastructure: 4 (high outsourcing costs).

2/ Luxury products group: 1 (high operating income margin and high marketing costs); travel agency: 2 (very low operating income, very high cost of sales, no R&D); telecom equipment supplier: 3 (high R&D costs); stationery products group: 4 (high marketing costs but lower than for the luxury products group); cement group: 5 (the last one! Limited R&D).