Chapter 50

Managing financial risks

Forbidden, but useful, tools …

The graph below illustrates the high volatility of some parameters of importance for the profit and loss account of companies: exchange rate (dollar/euro), interest rate (Eonia), raw materials (copper), and services (freight rates).

Source: Datastream - copper spot price in $ per MT: London Metal Exchange - Fret price: Baltic Dry Index

Accordingly, investors, supervisory authorities and managers pay more and more attention to risk management. This has led to:

- a regulatory framework imposing communication on procedures to identify and assess risks for the firm and on strategy for management of those risks and its efficiency;

- increasing pressure from capital markets to show more transparency. Guidance to better governance hints at reinforcing the power of directors in the management of risks through the implementation of risk audit committees;

- awareness of management teams of the importance of risk monitoring that leads to the setting up or the reinforcement of departments dedicated to risk management (internal audit, risk managers).

The evolution of risk management in recent years has consisted in increasingly segmenting risks and developing products that offer more accurate and flexible hedging for risk that in the past had not always been well assessed.

Section 50.1 Introduction to risk management

1/ Definition of risk

The key features of risk are:

- intensity of the possible loss on the amount of the exposure;

- frequency, which is the likelihood of this loss occurring (insurers talk about loss probability).

Risk can be classified into four major categories:

- Risk fundamentally linked to market changes (interest and exchange rates, raw material prices). The likelihood of occurrence of fundamental risk, i.e. the probability that the market will move against the interests of the company, is mechanically close to 50%. The intensity of the loss will depend on the volatility of the market in question.

- Loss probability refers to the likelihood of the loss occurring on a recurrent basis (such as losses on bad debts, the unknown losses suffered by mass market retailers on marked-down products, damage caused to vehicles by car rental companies, etc.). This is more of a statistical cost than a risk. The real risk is the possibility that a probable loss will occur more suddenly than usual, hence its name.

- Volatility risk is a risk that materialises during an exceptional year (fire in a hypermarket). This sort of risk should always be covered.

- A disaster risk materialises once a century (for example, the explosion at the BP oil refinery in the Gulf of Mexico) but it can have a very high level of intensity. It is difficult to cover1 and it is not unusual for the risk of a disaster occurring to be only partially covered, or not covered at all, given the fact that it is very unlikely to occur.

2/ Risk management steps

The different steps involved in risk management are as follows:

- Identification: the map-making work involved in risks. Once the intensity and probability of the risk has been identified and determined, it can be classified.

- Determination of existing internal controls which will help to mitigate the risk. This step involves assessing and testing existing internal controls (adequacy and efficiency). Controls should, in fact, lead to the substantial reduction (and generally at a low cost) of most risks, acting as a sort of filter. So it would be counterproductive for a company to insure its losses on receivables if it hadn't put in place basic controls to ensure their recovery (monitoring of outstanding payables, sending out reminders, etc.).

Prevention is often the best form of internal control. There is the very telling example of the manager of a transport firm who sent all of his drivers off for driving lessons in order to reduce the firm's accident rate.

- Determination of a residual risk and assessment: internal control generally manages and eliminates a large part of the risk that is easy to master. This leaves the company in a position where it can determine the residual risk. It then only has to assess the potential impact which will be a determining factor in the final phase.

- Definition of a management strategy: this involves finding the answers to two key questions:

- Am I in a position to manage this risk internally? If so, what is the cost?

- Are there any tools that can be used to hedge against this risk? If so, what is the cost?

Managers will rely on an assessment of the relationship between the level of hedging and the cost of each strategy to help them come to a decision. However, the choice of whether to cover a risk or not is not a simple yes or no decision, as it may first appear. Often, the best solution turns out to be an intelligent combination of a number of options.

However, issues relating to corporate image and communication may interfere with this purely economic reasoning. For example, a company may have to opt for more expensive hedging if this ties in with its image as a good corporate citizen. There are also some financial directors who may question whether the company should take out insurance against certain risks that will need to be booked at fair value (as required under IAS 39) and which would be likely to introduce high levels of volatility onto the income statement!

Insuring against risks helps to limit the volatility of earnings and cash flows. Nevertheless, the reader, who will by now have developed the reasoning of a skilled theoretician, could quite rightly point out that, as the risks covered are by nature diversified risks, eliminating them through insurance is not remunerated by the investor in the form of a lower required rate of return.2 In other words, the coverage does not create value. This is true from a purely logical point of view of efficient markets.

Looking at the issue in terms of agency theory, it is clear that managers should reduce the volatility of cash flows. Even if the hedging decision does not create value, a company that is less exposed to the ups and downs of the market is, from a manager's point of view, in a more comfortable position. Comprehensive insurance will enable management to implement a long-term strategy by reducing the likelihood of bankruptcy and reducing the personal risk of managers.

Campello, Lin, Ma and Zou (2011) have demonstrated that a company that hedges its financial risks benefits from a lower cost of debt and from less restrictive covenants. Lenders do not like specific risks.

Finally, Rountree, Weston and Allayannis (2008) have shown that an increase by 1% of the volatility of cash flows results in a decrease of enterprise value by 0.15%. Shareholders do not like the lack of hedging either and it is rare that a company does not hedge, at least partially, the financial risks that it can hedge.

3/ The different types of risk

Risks run by companies can be split into five categories:

- Market risk is exposure to unfavourable trends in product prices, interest rates, exchange rates, raw material prices or stock prices. Market risk occurs at various levels:

- a position (a) debt, for example, or an expected receipt of revenue in foreign currencies, etc.);

- a business activity (e.g. purchases paid in a currency other than that in which the products are sold); or

- a portfolio (short- and long-term financial holdings).

- Counterparty or credit risk. This is the risk of loss on an outstanding receivable or, more generally, on a debt that is not paid on time. It naturally depends on three parameters: the amount of the debt, the likelihood of default and the portion of the debt that will be collected in the event of a default.

- Liquidity risk is the impossibility at a given moment of meeting a debt payment, because:

- the company no longer has assets that can rapidly be turned into cash;

- a financial crisis (a) market crash, for example) has made it very difficult to liquidate assets, except at a very great loss in value; or

- it is impossible to find investors willing to offer new funding.

- Operating risks: these are risks of losses caused by errors on the part of employees, systems and processes, or by external events. They include:

- risk of deterioration of industrial facilities (accident, fire, explosion, etc.) that may also cover the risk of a temporary halt in business;

- technological risk: am I in a position to identify/anticipate the arrival of new technology which will make my own technology redundant?

- climate risks that may be of vital importance in some sectors, such as agriculture (how can cereal growers protect their harvests from the vagaries of the weather?) or the leisure sector (what sort of insurance should producers of outdoor concerts take out?);

- environmental risks: how can I ensure that I'm in a position to protect the environment from the potentially harmful impact of my activity? Am I in a position to certify that I comply with all environmental statutes and regulations in force?

- Political, regulatory and legal risks: these are risks that impact on the immediate environment of the company and that could substantially modify its competitive situation and even the business model itself.

Section 50.2 Measuring financial risks

We will now focus on financial risks.

Different financial risks are measured in very different ways. Measurement is quite sophisticated for market risks, for example, with the notion of position and value at risk (VaR), and for liquidity risks, less sophisticated for counterparty risks and quite unsatisfactory for other risks. Most risk measurement tools were initially developed by banks – whose activities make them highly exposed to financial risks – before being gradually adopted by other companies.

1/ Position and measurement of market risks

Market risk is exposure to fluctuations in value of an asset called the underlying asset. An operator's position is the residual market exposure on his balance sheet at any given moment.

When an operator has bought more in an underlying asset than he has sold, he is long (for interest or exchange rate a long position is when the underlying asset is worth more than the corresponding liability). It is possible, for example, to be long in euros, long in bonds or long three months out (i.e. having lent more than borrowed three months out). The market risk on a long position is the risk of a fall in market value of the underlying asset (or an increase in interest rates).

On the other hand, when an operator has sold more in the underlying asset than he has bought, he is said to be short. The market risk on a short position is the risk of an increase in market value of the underlying asset (or a fall in interest rates).

The notion of position is very important for banks operating on the fixed-income and currency markets. Generally speaking, traders are allowed to keep a given amount in an open position, depending on their expectations. However, clients buy and sell products constantly, each time modifying traders' positions. At a given moment, a trader could even have a position that runs counter to his expectations. Whenever this is the case, he can close out his position (by realising a transaction that cancels out his position) in the interbank market.

2/ Companies' market positions

Like banks, at any given moment an industrial company can have positions vis-à-vis the various categories of risk (the most common being currency and interest rate risk). Such positions do not generally arise from the company's choice or a purchase of derivatives, but are rather a natural consequence of its business activities, financing and the geographical location of its subsidiaries. A company's aggregate position results from the following three items:

- its commercial position;

- its financial position;

- its accounting position.

Let us first consider currency risk. Exposure to currency risk arises first of all from the purchases and sales of currencies that a company makes in the course of carrying out its business activities. Let us say, for example, that a eurozone company is due to receive $10m in six months, and has no dollar payables at the same date. That company is said to be long in six-month dollars. Depending on the company's business cycle, the actual timeframe can range from a few days to several years (if the order backlog is equivalent to several years of revenues). The company must therefore quantify its total currency risk exposure by setting receipts against expenditure, currency by currency, at the level of existing billings and forecast billings. By doing so, it obtains its commercial currency position.

However, the company's commercial exchange position goes well beyond the one-off transaction described above. Take, for example, a company such as Airbus, which gets its revenues in dollars but pays its costs in euros. Even if it hedges against foreign exchange losses on its orders, it will still be exposed over the long term to fluctuating exchange rates. The group cannot hedge against possible losses several years in advance on sales that it has not yet made! Its commercial position is thus structural and it is obvious that this position is even more precarious when the company's competitors are not in the same position. Boeing, for example, earns its revenues and pays its costs in dollars.

Hedging of commercial cash flows that are not contractual rarely covers over a few quarters, as this would be taking too high a risk if exchange rates were to move in the wrong direction. It allows the firm time to take corrective actions: increase sales prices, delocalise production, reduce costs, bill clients in a different currency, etc.

There is also a risk in holding financial assets and liabilities denominated in foreign currencies. If our eurozone company has raised funds in dollars, it is now short in dollars, as some of its liabilities are denominated in dollars with nothing to offset them on the asset side. The main sources of this risk are: (1) loans, borrowings and current accounts denominated in foreign currencies, with their related interest charges; and (2) investments in foreign currencies. Taken as a whole, these risks express companies' financial currency position.

The third component of currency risk is accounting currency risk, which arises from the consolidation of foreign subsidiaries. Equity denominated in foreign currencies, dividend flows, financial investments denominated in foreign currencies and currency translation differences3 give rise to accounting currency risk. Note, however, that this is reflected in the currency translation differential in the consolidated accounts and therefore has no impact on net income.

The same thing can apply to the interest rate risk. The commercial interest rate risk depends on the level of inflation of the currencies in which the goods are bought and sold, while the financial interest rate is obviously tied directly to the terms a company has obtained for its borrowings and investments. Floating-rate borrowings, for example, expose companies to an increase in the benchmark rate, while fixed-rate borrowings expose them to opportunity cost if they cannot take advantage of a possible cut in rates.

In addition to currencies and interest rates, other market-related risks require companies to take positions. In many sectors, for example, raw material prices are a key factor. A company can have a strategically important position in oil, coffee, semiconductors or electricity markets, for example.

3/ Value at risk (VaR) and corporate value at risk

VaR (value at risk) is a finer measure of market risk. It represents an investor's maximum potential loss on the value of an asset or a portfolio of financial assets and liabilities, based on the investment timeframe and a confidence interval. This potential loss is calculated on the basis of historical data or deduced from normal statistical laws.

Hence, a portfolio worth €100m with a VaR of €2.5m at 95% (calculated on a monthly basis) has just a 5% chance of shrinking more than €2.5m in one month.

VaR is often used by financial establishments as a tool in managing risk. VaR is beginning to be used by major industrial groups. Tele Danmark, for example, includes it in its annual reports. However, VaR has two drawbacks:

- it assumes that the markets follow normal distribution laws, an assumption that underestimates the frequency of extreme values;

- it tells us absolutely nothing about the potential loss that could occur when stepping outside the confidence interval.

Based on the above example, how much can be lost in those 5% of cases: €3m, €10m or €100m? VaR tells us nothing on this point, but stress scenarios can then be implemented. Stress tests computations (sensitivity, worst-case scenarios) can complete the information from the VaR. The average loss beyond the confidence interval (expected shortfall) measures the average loss over a certain period in x% of worst cases. The expected shortfall of €10m over one month and 5% means that over one month, the portfolio has a probability of 5% of suffering an average loss of €10m.

In the same way, some firms compute earnings at risk, cash flows at risk and corporate value at risk to measure the impact of adverse effects on earnings, cash flows and value over a longer period than for banks: from several months up to a year.

4/ Measuring other financial risks

Liquidity risk is measured by comparing contractual debt maturities with estimated future cash flow, via either a cash flow statement or curves such as those presented on page 208. Contracts carrying clauses on the company's financial ratios or ratings must not be included under debt maturing in more than one year because a worsening in the company's ratios or a downgrade could trigger early repayment of outstanding loans.

In addition to conventional financial analysis techniques and credit scoring, credit and counterparty risk is measured mainly via tests that break down risks. Such tests include the proportion of the company's top 10 clients in total receivables, number of clients with credit lines above a certain level, etc.

The measure of political risk is still in its infancy.

Section 50.3 Principles of financial risk management

Financial risk management comes in four forms:

- self-hedging, a seemingly passive stance that is taken only by a few, very large, companies and only on some of their risks;

- locking in prices or rates for a future transaction, which has the drawback of preventing the company from benefiting from a favourable shift in prices or rates;

- insurance, which consists in paying a premium in some form to a third party, which will then assume the risk, if it materialises; this approach allows the company to benefit from a favourable shift in prices or rates;

- immediate disposal of a risky asset or liability.

1/ Self-hedging

Self-hedging is only a strategy for hedging against risk when it is deliberately chosen by the company or when there is no other alternative (uninsurable risks). It can be structured to a greater or lesser extent. At one extreme, we get risk taking (no hedging after the risk has been analysed) and at the other, the setting up of a captive insurance scheme.

Self-hedging consists, in fact, in not hedging a risk. This is a reasonable strategy but only for very large groups. Such groups assume that the law of averages applies to them and that they are therefore certain to experience some negative events on a regular basis, such as devaluations, customer bankruptcy, etc. Risk thus becomes a certainty and, hence, a cost. Self-hedging is based on the principle that a company has no interest in passing on the risk (and the profit) to a third party. Rather than paying what amounts to an insurance premium, the company provisions a sum each year to meet claims that will inevitably occur, thus becoming its own insurer.

The risk can be diminished, but not eliminated, by natural hedges. A European company, for example, that sells in the US will also produce there, so that its costs can be in dollars rather than euros. It will take on debt in the US rather than in Europe, to set dollar-denominated liabilities against dollar-denominated assets.

Self-hedging is a strategy adopted by either irresponsible companies or a limited number of very large companies who serve as their own insurance company!

One sophisticated procedure consists in setting up a captive insurance company, which will invest the premiums thus saved to build up reserves in order to meet future claims. In the meantime, some of the risk can be sold on the reinsurance market.4

Setting up a captive insurance scheme is a complex operation, which takes the company into the realms of insurance. A captive insurance company is an insurance or reinsurance company that belongs to an industrial or commercial company, whose core business is not insurance. The purpose of the company's existence is to insure the risks of the group to which it belongs. This sort of setup sometimes becomes necessary because of the shortcomings of traditional insurance:

- some groups may be tempted to reduce risk prevention measures when they know that the insurance company will pay out if anything goes wrong;

- coverage capacities are limited and some risks are no longer insurable, for example gradual pollution or asbestos-related damage;

- good risks end up making up for bad risks.

The scheme works as follows: the captive insurance company collects premiums from the industrial or commercial company and its subsidiaries, and covers their insurance losses. Like all insurance companies, it reinsures part of its risks with international reinsurance companies. A captive insurance setup has the following advantages:

- much greater efficiency (involvement in its own loss profile, exclusion of credit risk, reduction of overinsurance, tailor-made policies);

- access to the reinsurance market;

- greater independence from insurance companies (having them compete against each other);

- reduction in vulnerability to cycles on the insurance market;

- possibility of tax optimisation;

- spreading the impact of losses over several financial years.

There is also the option of alternative risk financing. Well known for their fertile imaginations, insurers have come up with products that make it possible to spread the impact of insurance losses on the income statement. The insured pays an annual premium and, if a loss occurs, the premium is adjusted, if necessary, to cover the cost of the loss. IFRS has killed off these products, which did not transfer risk but merely allowed the consequences of a loss to be spread over several financial years.

2/ Locking in future prices or rates through forward transactions

Forward transactions can fully eliminate risk by locking in now the price or rate at which a transaction will be made in the future. This costs the company nothing but does prevent it from benefiting from a favourable shift in price or rates.

Forward transactions sometimes defy conventional logic, as they allow one to “sell” what one does not yet possess or to “buy” a product before it is available. However, they are not abstractions divorced from economic reality. As we will show, forward transactions can be broken down into the simple, familiar operations of spot purchasing or selling, borrowing and lending.

(a) Forward currency transactions

Let us take the example of a US company that is to receive €100m in euros in three months. Let's say the euro is currently trading at $1.5198. Unless the company treasurer is speculating on a rise in the euro, he wants to lock in today the exchange rate at which he will be able to sell these euros. So he offers to sell euros now that he will not receive for another three months. This is the essence of the forward transaction. Although forward transactions are common practice, it is worth looking at how they are calculated.

The transaction is tantamount to borrowing today the present value in euros of the sum that will be received in three months, exchanging it at the current rate and investing the corresponding amount in dollars for the same maturity.

Assume A is the amount in euros received by the company; N, the number of days between today and the date of receipt; R€, the euro borrowing rate; and R$, the dollar interest rate.

The amount borrowed today in euros is simply the value A, discounted at rate R€:

This amount is then exchanged at the RS spot rate and invested in dollars at rate R$. Future value is thus expressed as:

Thus:

The forward rate (FR) is that which equalises the future value in euros and the amount A.

Thus: If RS = $1.5198, N =90 days, R$ = 3.03% and R€ = 4.38%, we obtain a forward selling price of $1.5147.

A forward purchase of euros, in which the company treasurer pledges to buy euros in the future, is tantamount to the treasurer's buying the euros today while borrowing their corresponding value in dollars for the same period. The euros that have been bought are also invested during this time at the euro interest rate.

The forward exchange rate of a currency is based on the spot price and the interest rate differential between the foreign currency and the benchmark currency during the period covered by the transaction.

In our example, as interest rates are higher in euros than in dollars, the forward euro-into-dollar exchange rate is lower than the spot rate. The difference is called swap points. In our example, swap points come to 51.5 Swap points can be seen as compensation demanded by the treasurer in the forward transaction for borrowing in a high-yielding currency (the euro in our example), and investing in a low-yielding currency (the dollar in our example) up to the moment when the transaction is unwound. More generally, if the benchmark currency offers a lower interest rate than the foreign currency, the forward rate will be below the spot rate. Currency A is said to be at discount vis-à-vis currency B if A offers higher interest rates than B during the period concerned.

Similarly, currency A is said to be at premium vis-à-vis currency B if interest rates on A are below interest rates on B during the period concerned.

As in any forward transaction, treasurers know at what price they will be able to buy or sell their currencies, but will be unable to take advantage of any later opportunities. For example, if a treasurer sold his €100m forward at $1.5147, and the euro is trading at $1.5500 dollars at maturity, he will have to keep his word (unless he wants to break the futures contract, in which case he will have to pay a penalty) and bear an opportunity cost equal to $0.0353 per euro sold.

(b) Forward-forward rate and FRAs

Let us say our company treasurer learns that his company plans to install a new IT system, which will require a considerable outlay in equipment and software in three months. His cash flow projections show that, in three months, he will have to borrow €20m for six months.

On the euro money market, spot interest rates are as follows:

| 3 months | 1.35%–1.55% |

| 6 months | 1.63%–1.83% |

| 9 months | 1.81%–2.05% |

How can the treasurer hedge against a rise in short-term rates over the next three months? Armed with his knowledge of the yield curve, he can use the procedures discussed below to lock in the six-month rate as it will be in three months.

He decides to borrow €20m today for nine months and to reinvest it for the first three months. Assuming that he works directly at money market conditions, in nine months he will have to pay back:

But his three-month investment turns €20m into:

The implied rate obtained is called the forward-forward rate and is expressed as follows:

Our treasurer was thus able to hedge his exchange rate risk but has borrowed €20m from his bank, €20m that he will not be using for three months. Hence, he must bear the ?corresponding intermediation costs. His company's balance sheet and income statement will be affected by this transaction.

Now let's imagine that the bank finds out about our treasurer's concerns and offers him the following product:

- in three months' time, if the six-month (floating benchmark) rate is above 2.39% (the guaranteed rate), the bank pledges to pay him the difference between the market rate and 2.39% on a predetermined principal.

- in three months' time, if the six-month (floating benchmark) rate is below 2.39% (the guaranteed rate), the company will have to pay the bank the difference between 2.39% and the market rate on the same predetermined principal.

This is called a forward rate agreement, or FRA. An FRA allows the treasurer to hedge against fluctuations in rates, without the amount of the transaction being actually ?borrowed or lent.

If, in three months' time, the six-month rate is 2.5%, our treasurer will borrow €20m at this high rate but will receive, on the same amount, the pro-rated difference between 2.5% and 2.39%. The actual cost of the loan will therefore be 2.39%. Similarly, if the six-month rate is 1.5%, the treasurer will have borrowed on favourable terms, but will have to pay the pro-rated difference between 2.39% and 1.5%.

The same reasoning applies if the treasurer wishes to invest any surplus funds. Such a transaction would involve FRA lending, as opposed to the FRA borrowing described above.

Forward rate agreements are used to lock in an interest rate for a future transaction.

The notional amount is the theoretical amount to which the difference between the guaranteed rate and the floating rate is applied. The notional amount is never exchanged between the buyer and seller of an FRA. The interest rate differential is not paid at the maturity of the underlying loan but is discounted and paid at the maturity of the FRA.

An FRA is free of charge but, of course, the “purchase” of an FRA and the “sale” of an FRA are not made at the same interest rate. As in all financial products, a margin separates the rate charged on a six-month loan in three months' time and the rate at which that money can be invested over the same period of time.

Banks are key operators on the FRA market and offer companies the opportunity to buy or sell FRAs with maturities generally shorter than one year.

(c) Swaps

In its broadest sense, a swap is an exchange of financial assets or flows between two entities during a certain period of time. Both operators must, of course, believe the transaction to be to their advantage.

“Swap” in everyday parlance means an exchange of financial flows (calculated on the basis of a theoretical benchmark called a notional) between two entities during a given period of time. Such financial flows can be:

- currency swaps without principal;

- interest rate swaps (IRS);

- currency swaps with principal.

Unlike financial assets, financial flows are traded over the counter with no impact on the balance sheet, and allow the parties to modify the exchange or interest rate terms (or both simultaneously) on current or future assets or liabilities.

Interest rate swaps are a long-term portfolio of FRAs (from one to 15 years).

As with FRAs, the principle is to compare a floating rate and a guaranteed rate and to make up the difference without an exchange of principal. Interest rate swaps are especially suited for managing a company's long-term currency exposure.

For a company with long-term debt at 7% (at fixed rates) and wishing to benefit from the fall in interest rates that it expects, the simplest solution is to receive the fixed rate (7%) on a notional amount and to pay the floating rate on the same amount.

That is:

Fixed rate − Fixed rate − Floating rate = −Floating rate, tantamount to our company's borrowing the notional at a floating rate for the duration of the swap without its lenders seeing any change in their debts. After the first year, if the variable benchmark rate (Libor,6 Euribor,7 etc.) is 6%, the company will have paid its creditors an interest rate of 7%, but will receive 1% of the swap's notional amount. Its effective rate will be 6%.

The transaction described is a swap of fixed for floating rates, and all sorts of combinations are possible:

- swapping a fixed rate for a fixed rate (in the same currency);

- swapping floating rate 1 for floating rate 2 (called benchmark switching);

- swapping a fixed rate in currency 1 for a fixed rate in currency 2;

- swapping a fixed rate in currency 1 for a floating rate in currency 2;

- swapping a floating rate in currency 1 for a floating rate in currency 2.

These last three swaps come with an exchange of principal, as the two parties use different currencies. This exchange is generally done at the beginning and at the maturity of the swap at the same exchange rate. More sophisticated swaps make it possible to separate the benchmark rates from the currencies concerned.

The swaps market has experienced a considerable boom, and banks are key players. Company treasurers appreciate the flexibility of swaps, which allow them to choose the duration, the floating benchmark rate and the notional amount. Note, finally, that a swap between a bank and a company can be liquidated at any moment by calculating the present value of future cash flows at the market rate and comparing it to the initial notional amount. Swaps are also frequently used to manage interest rate risk on floating- or fixed-rate assets.

The difficulties that some emerging countries had in paying off their debt led to a boom in asset (and debt) swaps. They were meant to prevent too many risks from being heaped on the shoulders of a single debtor. The swaps work by allowing creditors to exchange one debt for another of the same type. Each country is rated in terms of percentage of the nominal of the debt. Ratings can range from almost 0 (default) to 100% for the safest borrowers.

The concept of the swap has been enlarged with total return swaps. Two players swap the revenues and change in value of two different assets they own during a certain period of time. One of the assets is generally a short-term loan, the other one can be a share price index, a block of shares, a portfolio of bonds, etc.

3/ Insurance

Insurance allows companies to pay a premium to a third party, which assumes the risk if that risk materialises. If it doesn't, companies can benefit from a favourable trend in the parameter hedged (exchange rate, interest rates, solvency of a debtor, etc.).

Conceptually, insurance is based on the technique of options; the insurance premium paid corresponds to the value of the option purchased.

As we saw in Chapter 23, an option gives its holder the right to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specified price on a specified date, or to forego this right if the market offers better opportunities. See Chapter 23 for background, valuation and conditions in which options are used.

Options are an ideal management tool for company treasurers, as they help guarantee a price while still leaving some leeway. But, as our reader has learned, there are no miracles in finance and the option premium is the price of this freedom. Its cost can be prohibitive, particularly in the case of companies operating businesses with low sales margins.

Major international banks are market makers on all sorts of markets. Below we present the most commonly used options.

(a) Currency options

Currency options allow their holders to lock in an exchange rate in a particular currency while retaining the choice of realising a transaction at the spot market rate if it is more favourable. Of course, the strike price has to be compared with the forward rate and not the spot rate. Banks can theoretically list all types of options, although European-style options are the main ones traded.

While standardised contracts are listed, treasurers generally prefer the over-the-counter variety, as they are more flexible for choosing an amount (which can correspond exactly to the amount of the flow for companies), dates and strike prices. Options can be used in many ways. Some companies buy only options that are far out of the money and thus carry low premiums; in doing do, they seek to hedge against extreme events such as devaluations. Other companies set the strike price in line with their commercial needs or perhaps their expectations.

Given the often high cost of the premium, several imaginative (and risky) products have been developed, including average strike options, lookback options, options on options and barrier options.

Average strike options8 can be used to buy or sell currencies on the basis of the average exchange rate during the life of the option. The premium is thus lower, as less risk is taken by the seller and the buyer has a lower return potential.

Lookback options are options where the strike price is fixed at the lowest price reached by the underlying asset during the life of the call option, and at its highest price for a put option. This kind of option cancels all opportunity cost, consequently its premium is high.

Options on options are quite useful for companies bidding on a foreign project. The bid is made on the basis of a certain exchange rate, but let's say the rate has moved the wrong way by the time the company wins the contract. Options on options allow the company to hedge its currency exposure as soon as it submits its bid, by giving it the right to buy a currency option with a strike price close to the benchmark rate. If the company is not chosen for the bid, it simply gives up its option on the option. As the value of an option is below the value of the underlying asset, the value of an option on an option will be low.

Barrier options are surely the most frequently traded exotic products on the market. A barrier is a limit price which, when exceeded, knocks in or knocks out the option (i.e. creates or cancels the option). This reduces the risk to the seller and thus the premium to the buyer. For example, if the euro is trading at $1.5, US company treasurers who know they will have to buy euros in the future can ensure that they'll get a certain exchange rate by buying a euro call at $1.46, for example; and then, to reduce the premium, placing the knock-out barrier at $1.35. If the euro falls below $1.35 at any time during the life of the option, treasurers will find themselves without a hedge (but the market will have moved in their direction and at that moment the futures price will be far below the level at which they bought their options).

It's easy to imagine various combinations of barrier options (e.g. knock-out barrier above the current price or knock-in barrier below; options at various strike prices: one activated at the level where the other is deactivated, etc.). When a bank offers a new currency product with a strange earnings profile (a) staircase profile, for example), it is generally the combination of one (or several) barrier option(s) with other standard market products.

Barrier options are attractive but require careful management as treasurers must constantly keep up with exchange rates in order to maintain their hedging situation (and to rehedge, if the option is knocked out). Moreover, their own risk-management tools would not necessarily tell them the exact consequences of these products or their implied specifications.

(b) Interest rate options

The rules that apply to options in general obviously apply to interest rate options. For the financial market, the exact nature of the underlying asset is irrelevant to either the design or valuation of the option. As a result, many products are built around identical concepts and their degree of popularity is often a simple matter of fashion.

A cap allows borrowers to set a ceiling interest rate above which they no longer wish to borrow and they will receive the difference between the market rate and cap rate.

A floor allows lenders to set a minimum interest rate below which they do not wish to lend and they will receive the difference between the floor rate and the market rate.

A collar or rate tunnel involves both the purchase of a cap and the sale of a floor. This sets a zone of fluctuation in interest rates below which operators must pay the difference in rates between the market rate and the floor rate and above which the counterparty pays the differential. This combination reduces the cost of hedging, as the premium of the cap is paid partly or totally by the sale of the floor.

Do not be intimidated by these products, as the cap is none other than a call option on an FRA borrower. Similarly, the floor is just a call option on an FRA lender. In a sense, these products are long options on interest rates that give the implicit right to buy or sell bonds at a certain price. As we have seen, these products allow operators to set a borrowing or lending rate vis-à-vis the counterparty. These options are frequently used by operators to take positions on the long part of the yield curve.

Swaptions are options on swaps, and can be used to buy or sell the right to conclude a swap over a certain duration. The underlying swap is stated at the outset and is defined by its notional amount, maturity and the fixed and floating rate that are used as benchmarks.

Some banks have combined swaps with swaptions to produce what they call swaps that can be cancelled at no cost. Do not be too impressed by the lack of cost. This product is none other than a swap combined with an option to sell a swap. The premium of the option is not paid in cash but factored into the calculation of the swap rate.

Barrier interest rate options are similar to barrier currency options:

- either the option exists only if the benchmark rate reaches the barrier rate; or

- the option is knocked in only if the benchmark rate exceeds a set limit.

The presence of barriers reduces the option's premium. Company treasurers can combine these options with other products into a custom-made hedge. Like barrier currency options, barrier interest rate options often require careful management.

(c) Confirmed credit lines

In exchange for a commitment fee, a company can obtain short- and medium-term confirmed credit lines from banks, on which it can draw at any time for its cash needs. A confirmed credit line is like an option to take out a loan.

(d) Credit insurance

Insurance companies specialising in appraising default risk (Euler Hermes, Atradius, Coface, etc.) guarantee companies' payment of a debt in exchange for a premium equivalent to about 0.3% of the nominal.

(e) Credit derivatives

Credit derivatives, which emerged in 1995, are used to unlink the management of a credit risk on an asset or liability from the ownership of that asset or liability.

Developed and used first of all by financial institutions, credit derivatives are beginning to be used by major industrial and commercial groups. The purpose of these products is mainly to reduce the credit risk on some clients, which may account for an excessive portion of the credit portfolio. They can also be used to protect against a negative trend in margins on a future loan. Companies are marginal players on this market (less than 10% of volume, this share does not seem to be increasing).

Credit derivatives work very much like interest rate or currency options. Only the nature of the risk covered is different – the risk of default or rating downgrade instead of interest rate or currency risk.

The most conventional form of credit derivative is the credit default swap (or CDS). In these agreements one side buys protection against the default of its counterparty by paying a third party regularly and receiving from it the predetermined amount in the event of default. The credit risk is thus transferred from the buyer of protection (a) company, an investor, a bank) to a third party (an investor, an insurance company, etc.) in exchange for some compensation.

Credit derivatives are traded over the counter and play the same economic role as an insurance contract.

Meanwhile, a second category of derivatives has developed which is not an “insurance” type product but a “forward” type of product. Using these, companies can, from the start, set the spread of a bond to be issued in the future. The spread of an issue is thus bought and sold at a preset level. And, of course, wherever forward purchasing or selling exists, financial intermediaries will come up with the corresponding options. We thus end up with an insurance product called an option on future spreads!

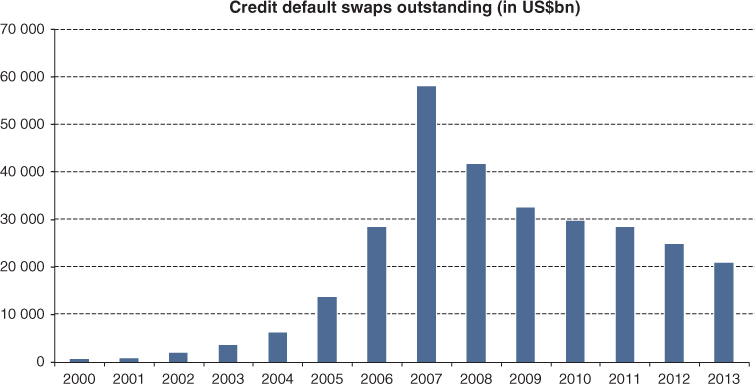

Source: Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

Exponential development until collapse in 2008; credit derivatives cover an existing risk or can be used to speculate.

(f) Political risk insurance

Political risk insurance is offered by specialised companies, such as Unistrat-Coface, Hermes and SACE, which can cover 90–95% of the value of an investment for as long as 15 years in most parts of the world. Risks normally covered include expropriation, nationalisation, confiscation and changes in legislation covering foreign investments. Initially the domain of public or quasi-public organisations, political risk insurance is increasingly being offered by the private sector.

Section 50.4 Organised markets – OTC markets

1/ Standardisation of contracts

In the forward transactions we looked at in Section 50.3, two operators concluded a contract, each exposing himself to counterparty risk if the other was in default at the delivery of the currency, for example, or before the maturity of the swap. Moreover, other operators were ignorant of the terms of these over-the-counter transactions, and the product's liquidity was unreliable. Liquidity is closely tied to the product's specificity, and usually dependent on the willingness of the counterparty to unwind the transaction.

It is because of these drawbacks that investors turn to standardised products that can be bought and sold on an organised market, such as a stock on the stock exchange. The futures and options markets have responded to this demand by offering:

- a fully liquid, listed product;

- with a clearing house; and

- specialised traders who act as intermediaries and ensure that the market functions properly.

Let's take the example of a three-month Euribor traded on Euronext-LIFFE, which has a €1m notional value. The contract matures on the twentieth day of March, June, September and December. It is listed in the form of 100 minus three-month Euribor and can thus be compared immediately with bond prices. The initial deposit is €500 per contract and the minimum fluctuation is 0.001%.

The high degree of standardisation in futures ensures fungibility of contracts and market liquidity. Liquidity is often greater on futures than on the underlying asset, as, unlike the underlying assets, futures volumes are not limited by the amount actually in issue.

Eurex, NYSE-LIFFE and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange are the main market places offering contracts for managing interest rates and commodity prices.

As listed contracts have become more liquid, standardised options have emerged on these contracts, which allow financial institutions and companies to take positions on the volatility of contract prices. Organised currency risk management markets are still in their infancy, as the dominance of banks in forward currency transactions constitutes an obstacle to the development of contracts of this type.

2/ Unwinding of contracts

In theory, when a contract matures, the buyer buys the agreed quantity of the underlying asset and pays the agreed price. Meanwhile, the seller of the contract receives the agreed price and delivers the agreed quantity of the underlying asset. This is the mechanism of delivery. For futures markets to be viable and to function properly, there must be at least the theoretical possibility of delivery. Possibility of physical delivery prevents the contract prices from being fully disconnected from price trends in the underlying asset. In other words, the value of the contract at maturity is equal to the value of the underlying asset at that time.

Let's take the example of an investor who, on 21 March, buys cocoa contracts maturing in July. Assume that the contract price is £2487 per tonne vs. a spot market price of £2500. Assume that, at the end of July, cocoa is quoted at £2600. By using futures contracts, our investor has bought the tonne of cocoa in July at £2487, whereas it is trading at £2600 on the market. Arbitrage trading makes the futures and spot prices converge at maturity. Let's assume that futures contracts were priced below the spot price. Investors would then snatch up these contracts at less than £2600 to instantly obtain (as the contract has now matured) cocoa that they can resell immediately for £2600. On the other hand, if the futures contracts were priced above £2600, no investor in his right mind would buy any (after all, who would buy cocoa for more than £2600 via futures contracts when they can buy at £2600 on the spot market?).

The value of a future at maturity is equal to the value of the underlying asset. The theoretical possibility of delivery prevents the contract price from coming unlinked from the price of the underlying asset at maturity.

However, prior to maturity, the difference between the spot price and future price, called the “base”, varies and is only rarely reduced to zero.

So much for the theory. In reality, in more than 95% of cases, no underlying asset is delivered, as this would be costly and administratively complicated. Let's look again at the example of the investor who bought contracts on cocoa at £2487 on 21 March and sells them at the end of July instead of taking delivery of the cocoa, since for him the result is the same. Indeed, what price would these futures be priced at except the cocoa spot price of £2600, which is also the futures price, since we are at maturity? Once the transaction is unwound, he will buy the cocoa on the spot market at £2600. This will cost him a total of £2487 (purchase of the contracts) + £2600 (reselling of the contracts) − £2600 (purchase of the cocoa), i.e. £2487 per tonne.

The mechanism of delivery exists only to allow arbitrage trading if, by chance, the price of contracts at maturity moves away from the price of the underlying asset. This is rather rare, as the markets regulate themselves. At maturity, buyers of contracts sell them to the sellers at a price that is equivalent to the price of the underlying asset at the time.

The purchase of a futures contract is normally unwound by selling it. The sale of a futures contract is normally unwound by buying it back.

3/ Eliminating counterparty risks

Derivatives markets offer considerable possibilities to investors, as long as everyone meets their commitments. The possibility of them not doing so is called counterparty risk. And such a risk, while small, does exist. For example, a contract could be so unfavourable for an operator that he might decide not to deliver the securities or funds promised, preferring to expose himself to a long legal process rather than suffer immediate losses. And even when everyone is operating in good faith, could not the bankruptcy of one operator create a domino effect, jeopardising several other commitments and considerable sums?

Unless specific measures are in place, counterparty risk should certainly be considered the main market risk. But, in fact, markets are organised to address this concern.

Derivatives market authorities may, at any time, demand that all buyers and sellers prove they are financially able to assume the risks they have taken on (i.e. they can bear the losses already incurred and even those that are possible the next day). They do so through the mechanism of the clearing, deposits and margin calls. The clearing house is, in fact, the sole counterparty of all market operators.

The buyer is not buying from the seller, but from the clearing house. The seller is not selling to the buyer, but to the clearing house. All operators are dealing with an organisation whose financial weight, reputation and functioning rules guarantee that all contracts will be honoured.

Clearing authorities watch over positions and demand a deposit on the day that a contract is concluded. This deposit normally covers two days of maximum loss.

Daily price movements create potential losses and gains relative to the transaction price. Each day, the clearing house credits or debits the account of each operator for this potential gain or loss.

When it is a loss, the clearing house makes a margin call – i.e. it demands an additional payment from the operator. Hence, the operator's account is always in the black at least by the amount of the initial deposit. If the operator does not meet a margin call, the clearing house closes out his position and uses the deposit to cover the loss.

For potential gains, the clearing house pays out a margin.

When the contract has exceeded the clearing house's maximum regulatory amount, price quotation is stopped and the clearing house makes further margin calls before quotation resumes.

4/ Important leverage effect

Margin calls are an integral component of derivatives markets. By limiting the amount of the initial deposit, margins provide considerable leverage to investors. Let's take the example of the cocoa contract above and try to work out the transaction's profitability. Our investor used futures contracts to buy July cocoa for £2487/tonne. At maturity it quotes at £2600 on the spot market, hence a £113 gain for a very limited outlay (just the deposit of £75). The return is considerable: 113/75 = 151%, whereas cocoa has gone up just (2600–2487) /2487 = 4.54%. Here is an example of the steep leverage of futures, but leverage can also work in reverse.

Such steep leverage explains why counterparty risk is never totally eliminated, despite precautions that are normally quite effective. Margin calls limit the extent of potential defaults to the losses that are incurred in one day, while the initial deposit is meant to cover unexpected events. However, the amounts at stake can, in a few hours, reach sums so high that all operators are shaken. Even if this happens only once in a while no clearing house has ever gone bust, even in the 2008 financial crisis. On the contrary, new clearing houses are expected to be created for OTC-traded products, like credit derivative swaps, so as to avoid the trouble caused on markets by the collapses of Lehman and AIG.

This leverage effect is not typical of organized derivative markets, it is typical of derivative products. The mechanics of a clearing house do not make it possible to eliminate this leverage but they ensure that at any point in time, each market player can meet the consequence of its positions. This theoretically avoids a chain reaction in case of bankruptcy. Market authorities are therefore seeking to increase the proportion of derivatives handled by clearing houses that offer a better protection against counterparty risk. This is now the case for a major part of interest rate swaps. There is still a long way to go, as demonstrated by the graph below:

Source: Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

OTC markets are much larger than organised markets due to interest swaps but this may change as a consequence of the 2008 financial crisis.

5/ A zero-sum game

Futures are a zero-sum game, as what one operator earns, another loses. The aggregate of market operators gets neither richer nor poorer (when excluding intermediation fees).

Let's take the above example of a tonne of cocoa quoted at £2600 at the end of July. We saw that the investor who bought contracts on 21 March has earned £113 per tonne. On the other side, the operator who sold those contracts on 21 March must deliver cocoa at the end of July for £2487, even though it is priced at £2600. He will thus lose £113, the exact amount that his counterparty has earned.

A zero-sum game, not a senseless game.

This is not only a zero-sum game but also a worthwhile game. Derivatives markets are there not to create wealth, but to spread risk and to improve the liquidity of the financial markets. On the whole, there is no wealth creation.

Summary

The summary of this chapter can be downloaded from www.vernimmen.com.

Managing risk inside a company has become a hot issue: regulations are much stricter, investors ask for more transparency and top management spends more time on it.

Risk management requires identification of risks, setting up controls, measuring the residual risk and lastly choosing a hedging strategy.

Risk is characterised by frequency and intensity.

We can identify five major risks:

- market risk – i.e. exposure of the company to unfavourable changes in interest and exchange rates or prices of raw materials or shares;

- counterparty risk – i.e. the loss of repayments of a debt in the event of default of the creditor;

- liquidity risk – i.e. the inability of a company to make its payments by their due date;

- operating risk – i.e. the losses caused by errors on the part of employees, systems and processes;

- political risk - i.e. the impacts on importers, exporters and companies that invest abroad.

Market risks are accurately measured with the notion of position and value at risk (VaR). Liquidity is measured by comparing debt repayment and expected cash receipts. Techniques for measuring other risks are still in their infancy.

When confronted with risk, a company can:

- decide to do nothing and take its own hedging measures. This will only apply to small risks or some very large corporates;

- lock in prices or rates for a future transaction by means of forwardation;

- insure against the risk by paying a premium to a third party which will then assume the risk if it materialises. This is the same idea that underlies options;

- immediately dispose of the risky asset or liability (securitisation, defeasance, factoring, etc.).

The same types of product (forward buying, put options, swaps, etc.) have been developed to cover the five different risks and are traded either on the OTC markets or on stock exchanges. On the OTC market, the company can find products that are perfectly suited to its needs, but there is the counterparty risk of the third party that provides the hedging. This problem is eliminated on the futures and options markets, although the price paid is reduced flexibility in tailoring products to companies' needs.

Questions

1/ What are the five financial risks that companies are exposed to?

2/ Describe four ways for a company to deal with risk.

3/ Use arbitrage to calculate forward selling of yen against euros at three months. What information do you need to do the calculation?

4/ What is an FRA?

5/ A Portuguese company imports maize from Mexico, which it in turn exports to Canada. The company pays and is paid at three months (the maize is, in fact, shipped direct from Mexico to Canada). Should it buy or sell a peso call option or a put option against the Canadian dollar?

6/ What is a future?

7/ What are the differences between OTC forward transactions and futures?

8/ What role does a clearing house play?

9/ Can credit derivatives be based on options?

10/ Does a derivative product have to be sufficiently liquid to be attractive?

11/ Can you provide examples of hedging products used by individuals?

12/ What category of derivative products would personal injury insurance fit into?

13/ Should corporate treasurers take advantage of any arbitrages that they detect on the markets?

14/ Should traders take advantage of any arbitrages that they detect on the markets?

15/ Excluding any costs, can a company hedge against all of its risks, taking the risk of opportunity into account? And the trader?

16/ A company is hedging more than its actual position. In doing so what is it actually doing?

More questions are waiting for you at www.vernimmen.com.

Exercises

1/ Calculate the future buy and sell price at three months (dollar against euro) using the following information:

- the three-month euro rate is equal to 4 6/8 – 4 7/8%;

- the three-month dollar rate is equal to 3 7/8 – 4%;

- the euro is currently trading at $1.0210/20.

2/ Calculate the six-month interest rate of the dollar on the basis of the following information:

- the six-month euro rate is equal to 4 4/8 – 4 5/8%;

- the euro is currently trading at $1.0210/20;

- the euro is trading at six months at $1.0150/60.

3/ A market trader is offering a $500m loan agreement in three months, for a period of three months, on the following terms: 3 3/4% – 3 7/8%. Using the information provided in Questions 1 and 2, can you identify an arbitrage opportunity? What is the potential gain for the arbitrageur?

4/ Is an arbitrage of this sort really without risk?

5/ If a corporate treasurer finds himself in the situation described above, should he execute the arbitrage?

Answers

Questions

1/ Market, liquidity, political, operational and counterparty risk.

2/ Self-hedging, locking in prices or interest rates now, taking out insurance, disposing of the risky asset or liability.

3/ See chapter. Three-month yen borrowing rate. Three-month euro investment rate. Yen/euro spot price.

4/ See chapter.

5/ Purchase of a call option.

6/ A forward buy or sell contract.

7/ Futures market = organised market.

8/ Eliminating counterparty risk.

9/ Yes.

10/ No – it is an OTC product.

11/ All insurance policies.

12/ A floor.

13/ No, there is no such thing as a perfect arbitrage, and there is always an element of speculation. Accordingly, it does not fall within the remit of a corporate treasurer.

14/ Yes, of course – that's what traders do.

15/ No, because it cannot wind up its business. Yes, because he can wind up his commitments.

16/ It is speculating.

Exercises

A detailed Excel version of the solutions is available at www.vernimmen.com.

1/ Three-month forward euro exchange rate: $1.0185 – $1.0201.

2/ Six-month dollar interest rate: 3.099% – 3.623%.

3/ You should borrow $495.2m at six months at 3.623%, invest it at 3 7/8% in dollars for three months (you will then have $500m in three months) and buy the traders' contract. The value of the arbitrage gain is $514 380 to be cashed in with no risk at maturity of the contract.

4/ No, there is always the counterparty risk of the trader offering the contract.

5/ No, because there is no way of measuring counterparty risk or any of the other market inefficiencies. For the corporate treasurer, this transaction would amount to financial speculation and, accordingly, would not form part of the ordinary course of the company's business.

Bibliography

On the theory behind the purpose and practice of hedging:

- T. Adam, C. Fernando, Hedging, speculation and shareholder value, Journal of Financial Economics, 81(2), 283–309, August 2006.

- K. Ben Khediri, D. Folus, Hedging and financing decisions, Bankers, Markets & Investors, 98, 28–38, January–February 2009.

- G. Brown, Managing foreign exchange risk with derivatives, Journal of Financial Economics, 60(2–3), 401–448, May 2001.

- G. Brown, K. Bjerre Toft, How firms should hedge, The Review of Financial Studies, 15(4), 1283–1324, Autumn 2002.

- M. Campello, Ch. Lui, Y. Ma, H. Zou, The real and financial implications of corporate hedging, Journal of Finance, 66(5), 1615–1647, October 2011.

- M. Faulkender, Hedging or market timing? Selecting the interest rate exposure of corporate debt, Journal of Finance, 60(2), 187–243, May 2001.

- G. Gay, C.-M. Lin, S. Smith, Corporate derivatives use and the cost of equity, Journal of Banking and Finance, 35(2011), 1491–1506, 2011.

- J. Graham, C. Harvey, The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field, Journal of Financial Economics, 60(2–3), 187–243, May 2001.

- P. Mackay, S. Moeller, The value of corporate risk management, Journal of Finance, 62(3), 1379–1419, June 2007.

- B. Rountree, J. Weston, G. Allayannis, Do investors value smooth performance?, Journal of Financial Economics, 90(3), 237–251, December 2008.

- J. Vickery, How and why do small firms manage interest rate risk? Journal of Financial Economics, 87(2), 446–470, 2008.

And for more about credit derivatives:

- G. Chacko, A. Sjöman, H. Motahashi, V. Dessain, Credit Derivatives: A Primer on Credit Risk, Modeling and Instruments, Wharton School Publishing, 2006.

- R. Douglas, Credit Derivatives Strategies: New Thinking on Managing Risk and Return, Bloomberg Press, 2007.

- A. Lipton, A. Rennie, The Oxford Handbook of Credit Derivatives, Oxford University Press, 2011.

- http://www.credit-deriv.com

On the transfer of alternative risks:

- K. Froot, The market for catastrophe risk: A clinical examination, Journal of Financial Economics, 60(2–3), 529–571, May 2001.

On value at risk:

- C. Alexander, Value-at-Risk Models, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2009.

- P. Jorion, Value at Risk, 3rd edn, McGraw-Hill, 2006.

- M. Leippold, Don't rely on VaR, Euromoney, 36–49, November 2004.

- www.gloriamundi.org

On political risk:

- M. Bouchet, E. Clark, B. Groslambert, Country Risk Assessment: A Guide to Global Investment Strategy, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003.

For a global view on risk: