Chapter 47

Bankruptcy and restructuring

Women and children first!

Every economic system needs mechanisms to ensure the optimal use of resources. Bankruptcy is the primary instrument for reallocating means of production from inefficient to efficient firms.

Theoretically, bankruptcy shakes out the bad apples from sectors in difficulty and allows profitable groups to prosper. Without efficient bankruptcy procedures, financial crises are longer and deeper.

A bankruptcy process can allow a company to reorganise, often requiring asset sales, a change in ownership and partial debt forgiveness on the part of creditors. In other cases, bankruptcy leads to liquidation–the death of the company.

Generally speaking, bankruptcy is triggered when a company can no longer meet its short-term commitments and thus faces a liquidity crisis. Nevertheless, the exact definition of the financial distress leading the company to file for bankruptcy may differ from one jurisdiction to another.

Bankruptcy is a critical juncture in the life of the firm. Not only does the bankruptcy require that each of the company's stakeholders make specific choices, but the very possibility of bankruptcy has an impact on the investment and financing strategies of healthy companies.

Section 47.1 Causes of bankruptcy

Companies do not encounter financial difficulties because they have too much debt, but because they are not profitable enough. A heavy debt burden does no more than accelerate financial difficulties.

The problems generally stem from an ill-conceived strategy, or because that strategy is not implemented properly for its sector (costs are too high, for example). As a result, profitability falls short of creditor expectations. If the company does not have a heavy debt burden, it can limp along for a certain period of time. Otherwise, financial difficulties rapidly start appearing.

Generally speaking, financial difficulties result either from a market problem, a cost problem or a combination of the two. The company may have been caught unawares by market changes and its products might not suit market demands (e.g. Virgin Megastore, a book and disk retailer, Silicon Graphics). Alternatively, the market may be too small for the number of companies competing in it (e.g., online book sales, satellite TV platforms in various countries). Ballooning costs compared with those of rivals can also lead to bankruptcy. General Motors, for example, was uncompetitive against other carmakers. Eurotunnel, meanwhile, spent twice the budgeted amount on digging the tunnel between France and the UK.

Nevertheless, a profitable company can encounter financial difficulties, too. For example, if a company's debt is primarily short term, it may have trouble rolling it over if liquidity is lacking on the financial markets. In this case, the most rational solution is to restructure the company's debt.

One of the fundamental goals of financial analysis as it is practised in commercial banks, whose main business is making loans to companies, is to identify the companies most likely to go belly up in the near or medium term and not lend to them. Numerous standardised tools have been developed to help banks identify bankruptcy risks as early as possible. This is the goal of credit scoring, which we analysed in Chapter 8.

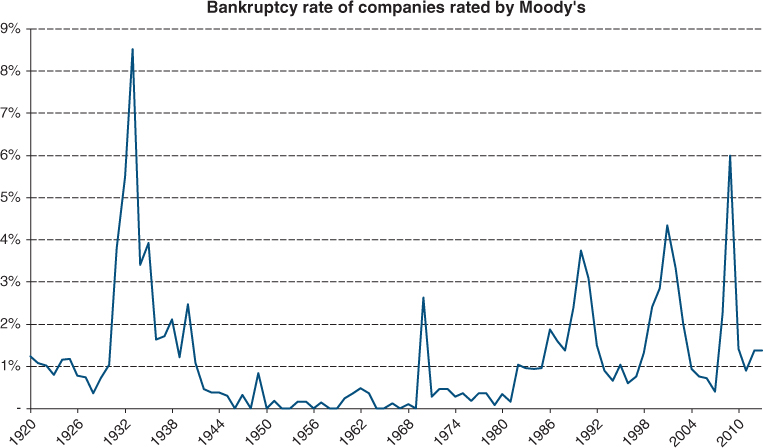

Rating agencies also estimate the probability that a company will go bankrupt in the short or long term (bankruptcies as a function of rating were presented in Chapter 20).

Source: Moody', 2013

Section 47.2 The different bankruptcy procedures

The bankruptcy process is one of the legal mechanisms that is the least standardised and homogenised around the world. Virtually all countries have different systems. In addition, legislation is generally recent and evolves rapidly.

Nevertheless, among the different procedures, some patterns can be found. In a nutshell, there are two different types of bankruptcy procedure. The process will be either “creditor (lender) friendly” or “debtor (company) friendly”. But all processes have the same ultimate goals, although they may rank differently:

- paying down the liabilities of the firm;

- minimising the disruptive impact on the industry;

- minimising the social impact.

1/ Creditor friendly and debtor friendly processes

A creditor-oriented process clearly sets the reimbursement of creditors as the main target of the bankruptcy process. In addition, the seniority of debt is of high importance and is therefore recognised in the procedure. In this type of procedure, creditors gain control, or at least retain substantial powers in the process. This type of process generally results in the liquidation of the firm. Bankruptcy procedure in the United Kingdom clearly falls into this category.

Such a regulation may seem unfair and too tough but it aims at preventing financial distress rather than solving it in the least disruptive way for the whole economy. In such countries, firms exercise a kind of self-discipline and tend to keep their level of debt reasonable in order to avoid financial distress. As a counterpart, creditors are more confident when granting loans, and money is more readily available to companies. For those supporting this type of process, the smaller number of bankruptcies in countries with stringent regulations (and an efficient judicial system) is evidence that this self-regulation works.

At the other end of the spectrum, some jurisdictions will give the maximum chance to the company to restructure. These procedures will generally allow management to stay in place and give sufficient time to come up with a restructuring plan. Countries with this approach include the USA (Chapter 11) and France.

To summarise, the following criteria help define a bankruptcy procedure:

- Does the procedure allow restructuring or does it systematically lead to liquidation (most jurisdictions design two distinct procedures) ?

- Does management stay in place or not?

- Does the procedure include secured debts? In some countries, secured debts (i.e. debts that are guaranteed by specific assets) and related assets are excluded from the process and treated separately, allowing greater certainty in the repayment. In such countries, securing a debt by a pledge on an asset gives strong guarantees.

- Do creditors take the lead, or at least have a say in the outcome of the process? In most jurisdictions, creditors vote on the plan that is proposed to them as the outcome of the bankruptcy process. They sometimes have even greater power and are allowed to name a trustee who will liquidate the assets to pay down debt. But in some countries (e.g. France) they are generally not even consulted.

| France | Germany | India | Italy | UK | USA | |

| Type | Debtor (borrower) friendly | Creditor (lender) friendly | Creditor (lender) friendly | Debtor (borrower) friendly | Creditor (lender) friendly | Debtor (borrower) friendly |

| Possible restructuring | Yes | Yes (rare) | Yes | Yes | Rare after opening of a proceeding | Yes |

| Management can stay in place | Yes* | Yes* | No | *** | No | Yes |

| Lenders vote on restructuring/ liquidation plan | No | Yes | Yes | Yes** | Yes | Yes |

| Priority rule | Salaries; tax, other social liabilities; part of secured debts; proceeding charges; other secured debts; other debts | Proceeding charges; secured debts; other debts | Secured debts and employee proceeding charges; tax and social liabilities; unsecured debts | Proceeding charges; preferential creditors (inc. tax and social) and secured creditors; unsecured creditors | Proceeding charges; secured debts on specific assets; tax and social security; other secured debts; other debts | Secured debts granted after filing; employee benefit and tax claims; unsecured debts |

* Assisted by court-designated trustee.

** Yes in the case of restructuring (pre-emptive arrangement) but only consultative committee in case of liquidation.

*** No in the case of liquidation.

Recasens (2001) has demonstrated that a creditor-orientated process is the most efficient. He reaches this conclusion after having compared the US system (debtor friendly) and the Canadian one (creditor friendly) on the basis of:

- the length and cost of the liquidation;

- the recovery rate according to seniority ranking;

- the risk of allowing a non-viable company to restructure and the risk of liquidating an efficient company.

He has noticed that creditor-orientated processes increase the debt offer. As a matter of fact it is logical that the offering of debt will be less abundant in countries where lenders are badly treated in case of difficulties experienced by their borrowers. Davydenko and Franks (2008) have demonstrated that British lenders recover 20% more on their claims than their French counterparts.

Claessens and Klapper (2002) have shown that the number of bankruptcies is greater in countries with mature financial markets. The proposed explanation is that, in those countries, companies are more likely to have public or syndicated debt and therefore a large number of creditors. In addition, with sophisticated markets, firms are more likely to have several types of debt: secured loans, senior debt, convertibles, subordinated, etc. In this context it may appear to be very difficult to restructure the firm privately (i.e. to find an agreement with a large number of parties with often conflicting interests such as hedge funds, vulture funds, trade suppliers, commercial banks, etc.), hence a bankruptcy process is the favoured route.

This is especially true when a lender has already hedged itself though a credit default swap1 and will earn more from bankruptcy (recover 100% of its claims thanks to the CDS) than in a reorganisation (will get less than 100%).

In bank-financing-based countries, firms have strong relationships with banks. In the case of financial distress, banks are likely to organise the restructuring privately. This is often the case in Germany or in France where bilateral relationships between banks and corporates are stronger than in the Anglo-Saxon world.

2/ An illustrative example of a bankruptcy

- In 1988, Virgin Megastore France opened a flagship store on the Champs-Élysées in Paris which was immediately a huge success. Other smaller stores were opened in the French provinces, based on the same concept of a cultural department store selling books, music, videos, concert tickets, etc.

- The company left the fold of the Virgin group, joining Lagardère in 2001, which sold it in 2007 to the private equity firm Butler Capital, who specialise in companies in difficulty that need to be turned around.

- The glory days were in fact over. Sales fell from €381m in 2008 to €286m in 2011 and the company continued to post losses. The incredible efficiency of Amazon, the ongoing development of digital music, books and videos at the expense of hardcopy formats and Virgin's slow development on the digital market explain a situation that just could not be turned around. Between 2011 and 2012, nine stores were closed and 200 employees lost their jobs.

- On 4 January 2013, Virgin Megastore announced that it was unable to meet its payments and filed for bankruptcy on 9 January. On 14 January, the Commercial Court of Paris opened an administration procedure with a four-month observation period. Offers to take over the company were made by Rougier et Plé, Vivarte and Cultura. These offers only covered some of the stores, at most 11 out of 26, and a third of the 960 remaining employees.

- On 23 May, the Commercial Court held that the offers were inadequate and gave the parties more time to improve or finalise their offers. On 10 June, the Court rejected the two offers that had not been withdrawn.

- On 12 June, the stores were closed to the public. On 17 June, the administration procedure was converted into liquidation proceedings and the company no longer existed. The premises it occupied were taken over by other businesses. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Section 47.3 Bankruptcy and financial theory

1/ The efficient markets hypothesis

In the efficient markets hypothesis, bankruptcy is nothing more than a reallocation of assets and liabilities to more efficient companies. It should not have an impact on investor wealth, because investors all hold perfectly diversified portfolios. Bankruptcy, therefore, is simply a reallocation of the portfolio.

The reality of bankruptcy is, however, much more complicated than a simple redistribution. Bankruptcy costs amount to a significant percentage of the total value of the company. By bankruptcy costs, we mean not only the direct costs, such as the cost of court proceedings, but also the indirect costs. These include loss of credibility vis-à-vis customers and suppliers, loss of certain business opportunities, etc. Almeida and Philippon have estimated that bankruptcy costs range at 4.5% of the enterprise value of the company (see Chapter 33).

2/ Signal theory and agency theory

The possibility of bankruptcy is a key element of signalling theory. An aggressive borrowing strategy sends a positive signal to the market, because company managers are showing their belief that future cash flows will be sufficient to meet the company's commitments. But this signal is credible only because there is also the threat of sanctions: if managers are wrong, the company goes bankrupt and incurs the related costs.

Moreover, conflicts between shareholders and creditors, as predicted by agency theory, appear only when the company is close to the financial precipice. When the company is in good health, creditors are indifferent to shareholder decisions. But any decision that makes bankruptcy more likely, even if this decision is highly likely to create value overall for the company, will be perceived negatively by the creditors.

Let's look at an example. Rainbow Ltd manufactures umbrellas and is expected to generate just one cash flow. To avoid having to calculate present values, we assume the company will receive the cash flow tomorrow. Tomorrow's cash flow will be one of two values, depending on the weather. Rainbow has borrowings and will have to pay 50 to its creditors tomorrow (principal and interest).

| Weather | Rain | Shine |

| Cash flow | 100 | 50 |

| Payment of principal and interest | −50 | −50 |

| Shareholders' portion of cash flow (equity) | 50 | 0 |

Rainbow now has an investment opportunity requiring an outlay of 40 and returning cash flow of 100 in case of rainy weather and −10 in case of sunny weather. The investment project appears to have a positive net present value. Let's see what happens if the investment is financed with additional borrowings.

| Weather | Rain | Shine |

| Cash flow | 200 | 40 |

| Payment of principal and interest | −90 | −40 (whereas 90 was due) |

| Shareholders' portion of cash flow (equity) | 110 | 0 |

Even though the investment project has a positive net present value, Rainbow's creditors will oppose the project because it endangers the repayment of part of their loans. Shareholders will, of course, try to undertake risky projects as it will more than double the value of the equity.

It can be demonstrated that when a company is close to bankruptcy, all financial decisions constitute a potential transfer of value between shareholders and creditors. Any decision that increases the company's overall risk profile (risky investment project, increase in debt coupled with a share buy-back) will transfer value from creditors to shareholders. Decisions that lower the risk of the company (e.g. capital increase) will transfer value from shareholders to creditors. As we showed in Chapter 34, these value transfers can be modelled using options theory.

Conflicts between shareholders and creditors and between senior and junior creditors also influence the decisions taken when the company is already in bankruptcy. On the one hand, creditors want to accelerate the procedure and liquidate assets quickly, because the value of assets rapidly decreases when the company is “in the tank”. On the other hand, shareholders and managers want to avoid liquidation for as long as possible because it signifies the end of all hope of turning the company around, without any financial reward. For managers, it means they will lose their jobs and their reputations will suffer. At the same time, managers, shareholders and creditors would all like to avoid the inefficiencies linked with liquidation. This common objective can make their disparate interests converge.

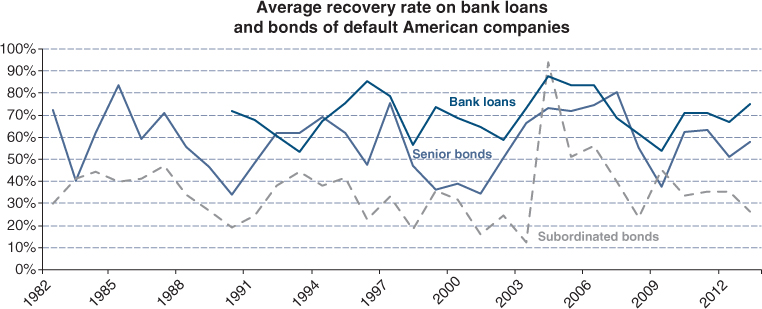

The table below shows the average hope for repayment in the case of bankruptcy, depending on the ranking of the debt.

Source: Moody's Global Credit Policy, February 2014

Whereas senior creditors get, on average, 60% of their money back, most junior creditors will receive less than 25% of their initial lending.

Lastly, a company in financial difficulties gives rise to the free rider problem (see Chapter 26). For example, a small bank participating in a large syndicated loan may prefer to see the other banks renegotiate their loans, while keeping the terms of its loan unchanged.

3/ The limits of limited liability

Modern economies are based largely on the concept of limited liability, under which a shareholder's commitment can never exceed the amount invested in the company. It is this rule that gives rise to the conflicts between creditors and shareholders and all other theoretical ramifications on this theme (agency theory).

In bankruptcy, managers can be required to cover liabilities in the event of gross negligence. In such cases, they can be forced to pay back creditors out of their own pockets, once the value of the company's assets is exhausted. So when majority shareholders are also the managers of the company, their responsibility is no longer limited to their investment. Such cases are outside the framework of the pure financial decision situations we have studied here.

Section 47.4 Restructuring plans

Restructurings concern companies which are considered to be viable, subject to certain conditions, often requiring operational changes in management, strategy, scope, production or marketing methods, etc.

Additionally, their capital structure must be adapted to a new environment because these companies, although they may be viable, do not and will not generate sufficient cash flows over a foreseeable period in order to cope with their current debts. Accordingly, these debts must be reduced one way or another, leading to sacrifices for both lenders and shareholders.

1/ The principles

When a company is simply in breach of a covenant (see page 714), it will negotiate a waiver with its banks in exchange for a commission of 0.5% to 1% of the total debt and a rise in the margins on the loans, the risk of which has increased (from 0.5% to 2% more than the initial margin, depending on the case).

If the company realises that it is not going to be able to meet the next repayment on its loan, it is strongly advised, with the help of an advisor, to commence private negotiations, known as private workouts, with its creditors. The more numerous the company's sources of funding – common shareholders, preferred shareholders, convertible bond holders, creditors, etc. – the more complex the negotiations.

The business plan submitted by the company in financial distress is a key element in estimating its ability to generate the cash flows needed to pay off creditors, partly or totally according to the seniority of their claims. It is usually validated through an Independent Business Review (IBR), carried out by a specialist firm.

A restructuring plan requires sacrifices from all of the company's stakeholders. It generally includes a recapitalisation, often funded primarily by the company's existing shareholders or by new shareholders who can thus take control over the company, and a renegotiation of the company's debt. Creditors are often asked to give up some of their claims, accept a moratorium on interest payments and/or reschedule principal payments or accept a swap of part of their debts into equity of the borrower.

The parties naturally have diverging interests, with each one seeking to minimise the reductions in value that it will have to agree to in order to enable the company to achieve a capital structure in line with economic conditions which have deteriorated.

The shareholders, who have already lost a lot of money, only want to put in a minimum amount of new equity, as long as an overall agreement can be reached and as long as they are confident in the company's ability to turn itself around. Sometimes, they are unable to put in any money as they have no resources (for example LBO funds at the end of their lives).

Lenders are, in theory, in a strong position thanks to the guarantees that they may have insisted on or their ability to take control of the company by converting part of their debts into shares in the case of an insolvency plan or court-ordered administration. In practice, they are not always keen or able to become shareholders, since this often involves providing new funds to finance the operational restructuring, which is a particularly risky investment. But under a debtor friendly system, it is not always clear who has the upper hand, since the aim of the lawmakers is first and foremost the preservation of the company and its jobs, not the preservation of the creditors.

Creditors and shareholders are naturally at odds with each other in a restructuring. To bring them all on board, the renegotiated debt agreements sometimes include clawback provisions, whereby the principal initially foregone will be repaid if the company's future profits exceed a certain level. Alternatively, creditors might be granted share warrants. If the restructuring is successful, warrants enable the creditors to reap part of the benefits.

This whole context explains that most restructuring negotiations finish in the early morning, after several all-night negotiating sessions, break-offs and unexpected dramatic turns in events. They end because there is a deadline which forces the parties to reach an agreement! To succeed, financial restructuring must be accompanied by operational restructuring allowing the return to a normal level of return on capital employed. Needless to say, it is the most important one! Working capital will have to be reduced as well as headcount, certain businesses might be sold or discontinued. Note that restructuring a company in difficulty can sometimes be a vicious circle. Faced with a liquidity crisis, the company must sell off its most profitable operations. But as it must do so quickly, it sells them for less than their fair value. The profitability of the remaining assets is therefore impaired, paving the way to new financial difficulties.

2/ An illustrative example

We have chosen to illustrate the process of financial restructuring using, as an example, Eurotunnel, the company that owns and operates the Channel tunnel between France and the UK, and the financial distress it experienced in 2006 and 2007. The case and figures have been intentionally simplified and could therefore appear to have been altered.

Back in 1986, Eurotunnel decided to take on debt rather than equity: it raised 4.7 times more debt (€7.6bn) than equity (€1.6bn) to finance the construction of the tunnel. The construction cost 80% more than expected (€16.7bn) and opened one year behind schedule. As a consequence, even after several equity issues, Eurotunnel had to bear a monumental debt (around €10bn) resulting in an unbearable amount of interest, which always exceeded its free cash flows.

A new CEO, appointed in 2005, started to improve the operating structure, reducing the number of employees, optimising the tunnel's capacity and changing the marketing strategy. He then started negotiations with creditors knowing that Eurotunnel would be unable to meet its financial commitments by early 2007.

The CEO stated repeatedly that he would not hesitate to declare Eurotunnel bankrupt, highlighting the fact that creditors, generally the most junior, would lose their entire investment in the process. Very basically, creditors were either senior (€3.7bn of debt) or junior (€5.4bn, such as bondholders). The CEO first had to convince creditors that, given the cash flow projections, a reasonable amount of debt could not exceed €4bn. His next task was to persuade the creditors to share the effort that had to be made by playing one category off against the other, always bearing in mind that shareholders, whose approval was compulsory, could veto a deal that would be too harsh on them, pushing the company into liquidation. He was helped by French bankruptcy law which does not allow creditors to automatically seize assets in the event of bankruptcy. After having spent the whole of 2006 in negotiations, an agreement was reached and approved by shareholders and creditors alike. But to reach this deal, the CEO had to seek the protection of the Paris Court, allowing Eurotunnel to suspend the payment of debts during the negotiation phase, and a receiver was appointed to help him.

The restructuring involved:

- the issue of a long-term loan of €4.2bn, of which €3.7bn was used to reimburse the senior debt. This new loan was at a lower interest rate and over a longer period of time than the old senior debt and it was compatible with the cash flow projections of Eurotunnel. The first debt repayment was postponed from 2007 to 2013 with the main repayments between 2018 and 2043;

- the transformation of the junior debt in mandatory convertible bonds into Eurotunnel shares. In addition, junior debtholders received some cash (€0.4bn) and warrants to subscribe in the future to new Eurotunnel shares at a price of €0.01 per share;

- of the €4.2bn loan, €0.1bn was left as a financial reserve;

- the issue of free warrants to shareholders parallel to those distributed to junior debtholders (55% for the former and 45% for the latter).

Eurotunnel shareholders were to receive 28% of the equity of the restructured group after conversion of the mandatory convertible bonds into new shares and the exercising of the warrants.

Basically, bondholders and other junior debtholders gave up all their claims to become owners of the group and received some cash. Prior to the plan, the debt (senior and junior) was trading at c. 44% of face value. The new loan is trading close to 100% of face value. Before restructuring, the market capitalisation of Eurotunnel was €0.7bn; after restructuring it increased by the exercise of warrants to c.€1.3bn.

For the shareholders and creditors the financial impact of the plan was as follows:

| Before restructuring (December 2005) | After restructuring (June 2007) | |

| Senior creditors | Nominal value: €3.7bn Market value: below nominal |

€3.7bn |

| Junior creditors | Nominal value: €5.4bn Market value: below 40% (i.e. €2.2bn) |

€2.6bn, of which mandatory convertible bonds for €1.7bn, warrants for €0.5bn and cash for €0.4bn |

| Shareholders | €0.7bn | €1.3bn, of which value of the shares for €0.7bn + value of warrants (€0.6bn) |

The CEO should be complimented on the good job he did for his shareholders. Junior creditors were in a weak negotiating position, as, in the event of liquidation, senior creditors would be allocated most of the assets because the face value of their claims was close to the value of the assets. However, we should not forget that, before restructuring, Eurotunnel shares were trading at 97% below the IPO price!

Summary

The summary of this chapter can be downloaded from www.vernimmen.com.

Bankruptcy is triggered when a company can no longer meet its short-term commitments and thus faces a liquidity crisis. This situation does not arise because the company has too much debt, but because it is not profitable enough. A heavy debt burden does no more than hasten the onset of financial difficulties.

The bankruptcy process is one of the legal mechanisms that is the least standardised and homogenised around the world. Virtually all countries have a different system. Depending on the country, the process will be either “creditor (lender) friendly” or “debtor (company) friendly”. But all processes have the same goals, although they might rank differently:

- paying down the liabilities of the firm;

- minimising the disruptive impact on the industry;

- minimising the social impact.

The bankruptcy process can generate two types of inefficiencies:

- allowing restructuring of an inefficient firm that destroys value;

- initiating the liquidation of efficient companies.

Prior to court proceedings, a company experiencing financial difficulties can try to implement a restructuring plan. The plan generally includes a recapitalisation and renegotiation of the company's debt.

Bankruptcy generates both direct (court proceedings, lawyers, fees, etc.) and indirect costs (loss of credibility vis-à-vis customers and suppliers, loss of certain business opportunities, etc.). These costs have an impact on a company's choice of financial structure.

Financial distress will generate conflict between shareholders and creditors (agency theory) and conflict among creditors (free rider issues).

Questions

1/ Why do companies go bankrupt?

2/ What risks do you take if you buy a subsidiary of a group that you know is in financial distress?

3/ Do the same types of conflict arise in the event of the bankruptcy of a partnership and that of a limited company? Why?

4/ How, in some countries, can bankruptcy play a role in the survival of the company?

5/ How do bankruptcy costs impact on the tax breaks available on debt?

6/ Why are companies that are emerging from bankruptcy proceedings often strong competitors?

7/ Why are companies in France that are emerging from bankruptcy proceedings rarely strong competitors?

8/ Can a company with no debts go bankrupt? Can it destroy value?

9/ Why is a company able to get back on its feet financially during the bankruptcy period?

10/ Why do creditors agree to grant loans to companies during the bankruptcy period?

11/ What are the pros of a creditor friendly bankruptcy procedure for shareholders?

12/ Name countries which have debtor friendly bankruptcy procedures.

More questions are waiting for you at www.vernimmen.com.

Exercises

1/ The Landmark car park will be shutting down tomorrow after having generated a final cash flow. It has debts of 500 used to finance its activities. Depending on whether the economic situation is good or bad (there is an equal probability of either), the flows are as follows:

| Economic situation | − | + |

| Operating cash flow | 500 | 1000 |

| Payment of debt | −500 | −500 |

| Shareholders' portion of cash flow | 0 | 500 |

The company is offered an investment yielding 0 if things go badly (−) and 300 if things go well (+).

- (a) What is the initial value of the debt? And of shareholders' equity?

- (b) What is the objective value of the investment project? At what price would investors be prepared to invest? Does your answer depend on the way this investment is financed?

- (c) What conditions would new creditors set for financing this new investment?

- (d) Are conflicts that arise between shareholders and creditors a result of the way in which the company finances investments?

2/ Alok Malpani and Sons is a high-tech group in financial distress. Its key financials are as follows:

| (in €m) | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

| Sales | 8026 | 5208 | 3018 |

| Operating income | 130 | (168) | (100) |

| Financial expense | (330) | (144) | (62) |

| Restructuring costs | (1020) | (314) | |

| Net income | (1220) | (626) | (162) |

| Fixed assets | 122 | 72 | |

| Working capital | 614 | 330 | |

| Shareholders' equity | (620) | (784) | |

| Subordinated debt | 616 | 616 | |

| Senior debt | 740 | 570 |

The Alok Malpani and Sons shares are trading at €24. The company's share capital is divided into 8 910 000 shares. The value of the senior debt can be estimated at half of its face value and the value of the subordinated debt at 21% of its face value.

The following rescue plan has been submitted to all of the investors in the company:

- Shareholder subscription to a capital increase of 15 500 000 new shares at a price of €20 per share, totalling €310m.

- Partial repayment and conversion of the subordinated debt into capital: issue of 3 850 000 new shares and repayment of €36.96m.

- Waiver of €160m of debts by senior creditors. In exchange, 1 250 000 warrants entitling holders to subscribe after three years to 1 share per warrant at a price of €25 per share. The value of these warrants is estimated at €4 per warrant. The proceeds of the capital increase that are left over after partial repayment of the subordinated debt will be used to repay the senior creditors.

- (a) What is your view of the financial health of this company?

- (b) Calculate the value of the different securities used to finance the capital employed.

- (c) Calculate how much the various lenders will have before and after the rescue plan. Assume the negotiated amount of the face value of the senior debt will be 80% after the plan.

- (d) Who are the key beneficiaries of this plan?

Answers

Questions

1/ Because their return on capital employed is too low and they do not generate enough free cash flow.

2/ The risk that the sale may be declared invalid, as it took place during the period immediately preceding the bankruptcy.

3/ No, because in partnerships, partners' liability is not limited to their contributions.

4/ It puts the counter back to zero for all contracts.

5/ The present value of the cost of bankruptcy is deducted from the enterprise value. The more debts a company has, the higher the bankruptcy costs.

6/ Because a portion of their charges may have been renegotiated and revised downwards (rent, personnel expenses, miscellaneous charges).

7/ Because in France, public policy is weighted heavily in favour of job preservation, and the recovery plan that saves the largest number of jobs is likely to be the one selected by the bankruptcy courts, even if, in the long term, it leads to the demise of the company.

8/ No, since it doesn't owe anything (or practically nothing). Yes, if it invests at a rate of return below that required by shareholders.

9/ Because in most jurisdictions, repayments on old debts are frozen, and customers continue to pay their debts.

10/ Because their new debts will be paid off before the old debts if the company is liquidated.

11/ Managers will try to postpone bankruptcy for as long as possible.

12/ USA, France.

Exercises

A detailed Excel version of the solutions is available at www.vernimmen.com.

1/

- (a) VD = 500, VE = 250.

- (b) 150; nearly 300 if it is debt financed; 150 if it is equity financed.

- (c) They would want to be certain that they will be reimbursed first (i.e. their credit is ranked higher than that of existing creditors).

- (d) Yes, but only because the company was close to bankruptcy at the outset.

2/

- (a) The group is in very poor shape financially, and its returns are far too low. The disposal of the most attractive assets that became necessary to meet cash needs merely served to accelerate the group's plunge into bankruptcy. The business is shrinking away.

- (b) Value of shareholders' equity = €213.84m.

- Value of subordinated debt = €129.36m.

- Value of senior debt = €285m.

- Value of capital employed = €628.2m.

- (c) Value of senior creditors' assets = (310 − 36.94) + (570 − 160 − 310 + 36.94) × 80% + 1.25 × 4 = €387.61m.

- Value of shareholders' equity = 628.2 − (570 − 160 − 310 + 36.94) × 80% − 1.25 × 4 = 513.65.

- Value of a share = 513.65/(8.91 + 15.5 + 3.85) = €18.2

Shareholders' wealth without capital increase = €162.2m (compared with €213.83m before plan).

Subordinated creditors' assets = 36.94 + 3.85 × 18.2 = €107m (compared with €129.36m before).

Wealth of shareholders who subscribed to the capital increase = 15.5 × 18.2 = €282.1m (for €310m invested).

- (d) The creditors.

Bibliography

- E. Altman, E. Hotchkiss, Corporate Financial Distress and Bankruptcy: Predict and Avoid Bankruptcy, Analyze and Invest in Distressed Debt, 3rd edn, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005.

- G. Andrade, S. Kaplan, How costly is financial (not economic) distress? Evidence from highly leveraged transactions that became distressed, Journal of Finance, 53(5), 1443–1493, October 1998.

- E. Berkovitch, R. Israel, Optimal bankruptcy laws across different economic systems, Review of Financial Studies, 12(2), 347–377, Summer 1999.

- A. Bris, I. Welch, N. Zhu, The costs of bankruptcy: Chapter 7 liquidation versus Chapter 11 reorganization, Journal of Finance, 61(3), 1253–1306, June 2006.

- J. Campbell, J. Hilscher, J. Szilagyi, In search of distress risk, Journal of Finance, 63(6), 2899–2939, December 2008.

- S. Claessens, L. Klapper, Bankruptcy Around the World–Explanation of its Relative Use, World Bank Development Research Group, July 2002.

- S. Davydenko, J. Franks, Do bankruptcy codes matter? A study of defaults in France, Germany, and the UK, Journal of Finance, 63(2), 565–608, April 2008.

- S. Djankov, O. Hart, C. McLiesh, A. Shleifer, Debt enforcement around the world, Journal of Political Economy, 116(6), 1105–1149, December 2008.

- I. Hashi, The economics of bankruptcy, reorganization, and liquidation: Lessons for East European transition economies, Russian and East European Finance and Trade, 33(4), 6–34, July/August 1999.

- U. Hege, Workouts, court-supervised reorganization and the choice between private and public debt, Journal of Corporate Finance, 9(2), 233–269, March 2003.

- J. McConnell, D. Denis, Corporate Restructuring, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2005.

- C. Molina, L. Preve, Trade receivables policy of distressed firms and its effect on the costs of financial distress, Financial Management, 38(3), 663–686, Autumn 2009.

- G. Recasens, Aléa moral, financement par dette bancaire et clémence de la loi sur les défaillances d'entreprises, Revue Finance, 22(1),65–86, June 2001.

- D.T. Stanley, M. Girth, Bankruptcy: Problem, Process, Reform, Brookings Institution, Washington, 1971.

- J. Warner, Bankruptcy costs: Some evidence, Journal of Finance, 32(2), 337–347, May 1977.

- L. Weiss, Bankruptcy resolution, direct costs and violation of priority of claims, Journal of Financial Economics, 27(2), 285–314, October 1990.

- M. White, The corporate bankruptcy decision, Journal of Economic Perspective, 3(2), 129–151, October 1989.

- G. Zhang, Emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy: Is it good news or bad news for industry competitors? Financial Management, 39(4), 1719–1742, Winter 2010.