1

Corporate Governance: An Overview

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- Capitalism at Crossroads

- Increasing Awareness

- Global Concerns

- What is Corporate Governance?

- Governance Is More Than Just Board Processes and Procedures

- A Historical Perspective of Corporate Governance

- Issues in Corporate Governance

Capitalism at Crossroads

The beginning of the twenty-first century was marked by the emergence of corporate governance, as a solution to the collapse of several high-profile corporations, both in the USA and elsewhere. The business world was shocked beyond belief with both the scale and degree of illegal and unethical corporate practices. As a result, “the need for the adoption of good corporate governance principles has been reinforced, and inevitably and inextricably, efforts to this end have gathered momentum every time a new corporate scandal came to light.”1

Corporates in the very citadel of capitalism, the United States of America, were mired in problems and were going through a grave crisis of credibility during the very early years of the new millennium. Companies that were held out till then as role-models in corporate governance were being threatened with widespread exposures of accounting irregularities and fraudulent practices. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) set up under the New Deal to combat the Great Depression, appeared to be inadequately equipped to deal with gigantic business conglomerates such as Xerox, WorldCom and Enron that committed deliberate frauds with a view to boosting their sales revenues and for showing highly inflated profits. If company managements want the market value of their equity shares to climb new peaks year after year, the temptation to fudge accounts and thereby take credit for unearned profits seem to be difficult to resist. Investors, on their part, can neither equate high profits shown by their companies as a sure index of corporate efficiency nor treat a company’s failure to maintain a consistent high profit a failure of corporate governance.

In the beginning of the new millennium, several companies in the USA and elsewhere faced collapse because of corporate misgovernance and unethical practices they indulged in. The then existing regulatory framework seemed to be inadequate to deal with the gigantic business conglomerates that committed deliberate frauds.

The problems of corporate America, as indeed of several developed and more so of developing economies such as India, have a lot to do with the failure of the auditing profession to safeguard consciously the interests of shareholders. There is a growing apprehension among users of audited accounts such as shareholders, financial institutions and banks, government, industry and the public at large, that all is not well with the profession of auditing. The collapse of US corporate giants has only heightened this perception.

In the past few years, the reported corporate lootings have become so frequent, so spectacular that the term “business ethics” seems to sound like a cruel oxymoron. The swashbuckling CEO, the archetypal corporate hero in prosperous times, is now villified as a crook, gambling away the retirement savings of hapless workers and other unwary investors.

America’s Hall of Shame—2002

Corporate America’s Hall of Shame was littered with failed mega corporations and transnational companies that sound like a virtual “who is who” of international business glitterati.

In the year 2000, several American mega corporations collapsed like a pack of cards. The federal administration of President Bush was quick to slap punitive measures on erring corporations and initiated preventive steps to avoid corporate frauds in future. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act made it mandatory for senior executives to certify reports under oath with the pain of severe penalties if proved wrong.

WorldCom improperly booked $3.8 billion in expenses, thus inflating profits. The founder, Bernie Ebbers, borrowed $408 million from the phone company to cover personal debts. Energy firm, Enron, created outside partnerships that helped hide its poor financial condition. Executives earned millions of dollars selling company stocks. The company had to go to bankruptcy court. The accounting firm, Andersen, was accused of shredding Enron documents and was convicted for obstruction of justice. Energy company, Dynegy, was under investigation for accounting and trading malpractices, in part related to California power crisis. Securities and Exchange Commission sued executives of garbage company Waste Management for massive accounting fraud from 1992 to 1997 that resulted in a $17 billion restatement of earnings. Its auditor was Arthur Andersen. Adelphia Communications made illegal loans to founder Rigas’ family members and was under investigation for accounting malpractices. Amid questions about its accounting malpractices, Tyco Chief Executive, L. Dennis Kozlowiski, was charged with deliberately dodging sales tax on purchase of artwork for his New York residence. Chief Executive, Samuel Waksal, of Imclone Systems was charged with insider trading after company’s drug application got rejected. Southern California software company Peregrine Systems said it might have overstated revenue by $100 million over three years. Three former executives of the drugstore chain Rite Aid were indicted for charges of securities and accounting fraud relating to irregularities in the 1990s.

The Bush Federal Administration was prompt to slap punitive measures on erring corporates and preventive steps to avoid future corporate frauds. The new law that has come into force, known as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, stipulates that chief executive officers (CEOs) and chief financial officers (CFOs) of big companies should swear in front of a notary that their annual and quarterly reports contain no untrue statement and have not omitted any material fact. Over the past few years, more and more companies have made a beeline to make the certification of the truthfulness of their accounting statements. It is now mandatory for both the CEO and the CFO to certify the annual report and also give an assurance that they meet internal controls relating to the circulation of material information regarding the company. This certification means that these officials will be liable for criminal or civil suits for any omissions, false statements and restatements.

Corporate Misgovernance in India

Industrial growth in India along with the development of corporate culture started only after the country became free in 1947. However, with the characteristic of the country’s governance continuing to be feudalistic, and its political system degenerating to be pseudo-democratic, the governance of most of the country’s industrial and business organisations thrived on unethical practices at the market place while showing scant regard for the timeless human and organisational values in dealing with their employees, shareholders and customers. The increasing corruption in the government and its various services had kept the managements of country’s industrial and business organisations above accountability for their misdeeds, encouraging them to indulge in more unethical practices. The state-owned organisations occupying a dominant position in the country’s economy and being monopolistic, passed on the costs of their corporate misgovernance to the helpless consumers of their products and services. Organisations in the private sector, barring a few, indulged in all possible unethical practices to fleece their customers on the one hand and denied the state its due on the other. In India, one could see a large number of privately owned business organisations too indulging in rampant corporate misgovernance. The difference is that while in state-owned organisations employees at all levels are seen to indulge in, or contribute to, corporate misgovernance, in privately owned business organisations only employees at top levels are seen to be indulging in corporate misgovernance, indicating that in privately owned business organisations employees at the lower levels of the corporation are better controlled. The scams committed in a number of large privately owned corporations during the last one decade clearly indicate the nature and extent of corporate misgovernance that exists in privately owned business organisations.

In India, the governance of most of the country’s industrial and business organisations thrived on unethical practices at the market place and showed scant regard for the timeless human and organisational values while dealing with their shareholders, employees and other stakeholders.

Series of Scams That Shook Investor Confidence

The vital need for corporate governance was first realised in the country with the “Big Bull,” Harshad Mehta’s securities scam that was uncovered in April 1992 involving a large number of banks and resulting in the stock market nosediving for the first time since the advent of reforms in 1991. This was followed by a sudden growth of cases in 1993 when transnational companies started consolidating their ownership by issuing equity allotments to their respective controlling groups at steep discounts to their market price. In this preferential allotment scam alone investors lost roughly Rs. 5,000 crore. The third scandal of the decade was the disappearance of the companies during 1993–94. Between July 1993 and September 1994, the stock market index shot up by 120 per cent. During this boom, 3,911 companies that raised over Rs. 25,000 crore vanished or did not set up their projects. Due to the vanishing companies scam, gullible investors lost a lot of money because during the artificial boom hundreds of obscure companies were allowed to make public issues at large share premia through high sales pitch of questionable investment banks and misleading prospectuses.

Another scam took place in 1995–96. Plantation companies scam saw Rs. 50,000 crore mopped up from gullible investors who were prompted to believe plantation schemes would yield huge returns. The so-called non-banking finance companies scam that took place in 1995–97 also saw more than Rs. 50,000 crore mopped up from the public promising them high returns but vanished. The mutual fund scam saw public sector banks raising between 1995–98 nearly Rs. 15,000 crore by promising huge fixed returns, but all of them flopped. Yet another scandal was the one in which BPL, Sterlite and Videocon price rigging happened with the help of Harshad Mehta. The IT scam between 1999–2000 saw firms change their names to include ‘infotech’, and investors saw their stocks run away overnight. The year 2001 witnessed yet another scam in which Ketan Parekh resorted to price rigging in association with a bear cartel. One of the most recent and scandalous scams that was said to be the worst compared to all the previous ones here and elsewhere was the Satyam scandal. The promoter of the country’s fourth largest IT company systematically siphoned off billions of rupees of shareholders’ wealth.

Illegal Tactics of Indian Corporates

Several illegal tactics used by corporates in India over the years are as follows:

- Cornering of industrial licenses mainly with a view to pre-empting competitors to enter into their well-entrenched industry.

- Using import licenses to make a quick profit in the market.

- Illegally holding money abroad to meet business expenses and investments for which government would not allow enough funds.

- Trying to gain special advantages for the business through bribery of concerned officials, generating unaccounted money in the business so as to compensate for penal levels of taxation other “business” expenses and political donations.

An overwhelmingly large number of Indian corporations used several illegal tactics such as cornering of industrial licenses with a view to keeping away competitors, using import licenses to make a quick profit, illegally holding money abroad, and indulging in bribery, corruption and other unethical practices with impunity.

The extraordinarily high income tax levels of the 1960s led many companies to devise tax evasion tactics in the form of compensation packages for their senior and middle level employees. These elements grew in value over the years, often crossing the lines of legality. Overseas holidays for families shown as business trips, expensive residences shown as in office use, cars for personal use but shown as being used for work, furniture and furnishings, clothing, food and most household expenses being met by the company for employees became relatively common practices for the companies which promised to be honest otherwise. The economy lost tax revenues and the organisations fostered an acceptance of ignoring and violating of laws that were regarded as unacceptable by the company. The net result of such dishonest practices and scams was that the regulators started tightening up especially in the last few years, also public patience ebbed and intolerance to such issues rose. This fuelled a change in the Indian corporate mindset. These scandals led to the realisation that “corporate governance” was essential and was advocated by financial press, some financial institutions, more enlightened business associations, the regulatory agencies and government.

It is strange but true that early initiative for better corporate governance in India came from the more enlightened listed companies and an industry association. This was quite different from the US or Great Britain, where the drivers of corporate governance were shareholders’ groups, activist funds and self-regulatory bodies within capital markets, or Southeast and East Asia, where it was the result of conditions imposed by the IMF and the World Bank in the wake of the financial collapse of 1997–98. When India embarked on its corporate governance movement in 1996–97, the country faced no financial or balance of payments crisis. There were no major internal or external pressures that could have created urgency for better corporate governance.

Reasons for Corporate Misgovernance

For too long, Indian corporates have insulated themselves from wholesome developments evolving elsewhere. A closed economy, a sheltered market, limited need and access to global business/trade, lack of competitive spirit and a regulatory framework that enjoined mere observance of rules and regulations rather than realisation of broader corporate objectives marked the contours of corporate management for well over 40 years, ever since we adopted a socialistic pattern of society.

Apart from forces militating against healthy and transparent governance is the fact that a vast majority of Indian corporates is controlled by promoter families which while owning a negligible proportion of share capital in their companies, rule them as if they are their personal fiefdoms. According to a survey conducted some years ago, family shareholdings in big business groups averaged a mere 3.3 per cent of the aggregate paid-up capital. Under the new economic policy, the fear of hostile raids has made several business houses enhance their stakes but the units still remain captive for a meagre stake. These so-called “owners” view with disdain any suggestion of professional management, which, after all, is the core and essence of corporate governance. In such an unhealthy scenario, corporate democracy, professionalisation of management and transparency of operations were mere rhetoric used to drum up support or elicit a degree of acceptability from gullible investors.

The reasons for the corporate misgovernance in India were many: A closed economy, a sheltered market, limited need and access to global business, lack of competitive spirit and an inefficient regulatory framework. These were responsible for the poor governance of companies in India for well over 40 years, between 1951 and 1991.

The perpetrators of misgovernance, however, have to face the winds of change in the form of market-driven reforms that are shaking their feeble foundations. Economic liberalisation, a steady dismantling of the control and quota regime, delicensing and deregulation of industries, changes in export-import and overall commercial policies, globalisation of the economy within and outside the ambit of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the entry of transnational corporations and the take-over bids in an open and competitive environment, have all ripped open the cocoons within which Indian corporates had laid out their cosy existence. These dramatic changes have exposed them to the merciless forces of international competition and forced them to shed their old ways if not switch over to newer norms of corporate governance.

Increasing Awareness

Thus, in the aftermath of economic liberalisation, corporate heavyweights have started mulling over the buzz phrase of corporate governance in hastily convened conclaves and conferences. Apart from the Department of Company Affairs and the Institute of Company Secretaries, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), which has worked out a code of corporate governance, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and the Association of Mutual Funds in India (AMFI) just to name a few apex bodies, have discussed it with all the seriousness it deserved. The Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI) has implemented an internal corporate governance code about ten years ago.

In the aftermath of the pioneering Cadbury Report and economic liberalisation in India, corporate governance gained greater currency and importance in the country. The Department of Company Affairs, the Institute of Company Secretaries and trade associations such as the CII and FICCI, capital market regulator, SEBI and companies such as ICICI took the lead in discussing it and recommending its implementation. By April 2003, every listed company adopted the SEBI code of corporate governance.

The corporate governance movement in India began in 1997 with a voluntary code framed by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). In the next three years, almost 30 large listed companies accounting for over 25 per cent of India’s market capitalisation voluntarily adopted the CII code. By 1999, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI)—India’s capital market regulator—got into the act and set up a committee headed by Kumar Mangalam Birla to mandate international standards of corporate governance for listed companies. From 1 April 2001, over 140 listed companies accounting for almost 80 per cent of market capitalisation started following a mandatory code which was in line with some of the best international practices. By April 2003, each and every listed company joined the SEBI code.

How did this sea change occur without the presence of sufficient internal or external pressures? The answer has to do a lot with the change in corporate mindset brought about by economic liberalisation and competition of the 1990s. It is useful to emphasise here the great churning that has been unleashed by a decade of liberalisation. Consider the top 100 companies ranked according to market capitalisation as on 1 April 1991. How has the market treated these companies a couple of years after liberalisation? Very poorly! that is what the market statistics of the time tell us. Simply, yesterday’s giants—those who lived off protection and cared precious little for generating greater shareholder value—have been dwarfed by market forces. Compare this with the new players in the corporate sector. They have been doing well. This evidence shows how economic liberalisation, competitiveness and dismantling of controls have reduced entry barriers, and permitted new entrepreneurs to race to the top.

This change has augured well for corporate governance. The new breed of managers is not wedded to the mechanics of yesterday’s regime. Instead, they believe in professionalism and the credo of running business transparently to increase corporate value. Thus, the need for good corporate governance is being appreciated as a sound business strategy, and as an important facilitator to tap domestic as well as international capital.

Global Concerns

There are fewer concerns more central to international business and developmental agendas than that of corporate governance. A series of events over the last two decades have placed corporate governance issues at the centre stage both for the international business community and for international financial institutions. Apart from colossal business failures and serious frauds in the USA, several high-profile scandals in Russia and the Asian crisis have brought corporate governance issues to the forefront in developing countries and transition economies. The virtual collapse of the Russian economy in 1998 resulted in large measure from the weakness of governance mechanisms. The abysmal inefficiency of business operations under state control led to the earlier collapse of the Soviet system. But privatisation of industries resulted in a substantial diversion of assets by managers. These managers are said to have robbed share holders, creditors, consumers, the government, workers, in sum all possible stake holders, an estimated $100 billion and this colossal sum was moved out of the country by these predators. The consequent distrust predictably resulted in the virtual collapse of external capital to firms, illustrating vividly the fact that corporate misgovernance can shake the very foundations of a society, affecting every member therefrom. Likewise, the Asian financial crisis also demonstrated that even strong economies lacking transparent control, responsible corporate boards and share holder rights can collapse quickly as investors’ confidence erodes.

Further, national business communities are gradually realising the fact that there is no substitute for getting the basic business and management systems in place in order to be competitive in the global market and to attract foreign investment.

What is Corporate Governance?

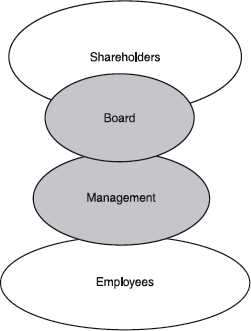

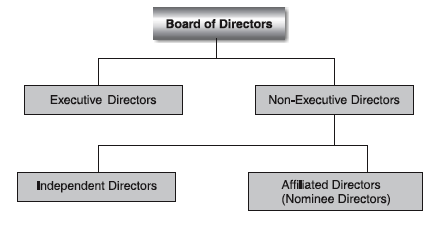

Corporate governance is typically perceived by academic literature as dealing with “problems that result from the separation of ownership and control.” From this perspective, corporate governance would focus on: The internal structure and rules of the board of directors; the creation of independent audit committees; rules for disclosure of information to shareholders and creditors; and, control of the management. Figure 1.1 explains how a corporation is structured.

Figure 1.1 Separation of ownership and management

Definitions of Corporate Governance

The concept of corporate governance sounds simple and unambiguous, but when one attempts to define it and scan available literature to look for precedence, one comes across a bewildering variety of perceptions behind available definitions. The definition varies according to the sensitivity of the analyst, the context of varying degrees of development and from the standpoint of academics versus corporate managements. However, there is an underlying uniformity in the thinking of all analysts that there is a definite need to eradicate corporate misgovernance and promote corporate governance at all costs. It is not only the stakeholders who are keenly interested in ensuring adoption of best governance practices by corporates, but all societies and countries worldwide.

From the Academic Point of View

From the academic standpoint, corporate governance is seen as one that addresses “the problems that result from the separation of ownership and control.”2 Viewed from this perspective, corporate governance focusses on some structures and mechanisms that would ensure the proper internal structure and rules of the board of directors; creation of independent committees; rules for disclosure of information to shareholders and creditors; transparency of operations and an impeccable process of decision-making; and control of management.

A recent academic survey of corporate governance defined it as follows: “Corporate governance deals with the ways in which suppliers of finance to corporations assure themselves of getting a return on their investment. How do the suppliers of finance get managers to return some of the profits to them? How do they make sure that managers do not steal the capital they supply or invest it in bad projects? How do suppliers of finance control managers?”3

From this point of view, corporate governance tends to focus on a simple model:

- Shareholders elect directors who represent them.

- Directors vote on key matters and adopt the majority decision.

- Decisions are made in a transparent manner so that shareholders and others can hold directors accountable.

- The company adopts accounting standards to generate the information necessary for directors, investors and other stakeholders to make decisions.

- The company’s policies and practices adhere to applicable national, state and local laws.4

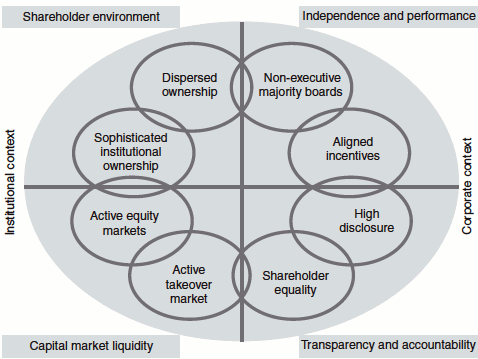

A McKinsey & Company Report published in 2001 under the title “Giving New Life to the Corporate Governance Reform Agenda for Emerging Markets” suggests that by using a two-version “governance” chain model, we can illustrate the governance practices throughout the world.

Model 1

In the first version of McKinsey’s model called “The Market Model” governance chain, there are efficient, well-developed equity markets and dispersed ownership, something common in the developed industrial nations such as the US, UK, Canada and Australia. Corporate governance is basically how companies deal fairly with problems that arise from “separation of ownership and effective control.” This model illustrates conditions and governance practices that are better understood and appreciated and as such highly valued by sophisticated global investors.

Figure 1.2 The “market model” governance chain (more common in the US, the UK, Canada and Australia)

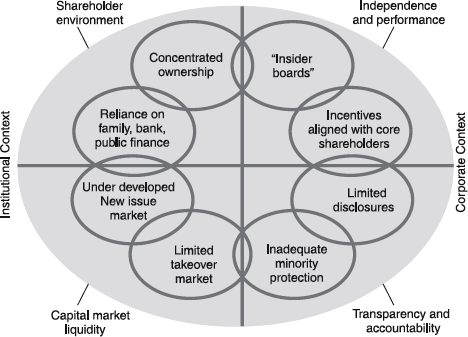

Model 2

In the second version of McKinsey’s model called “The Control Model,” governance chain is represented by underdeveloped equity markets, concentrated (family) ownership, less shareholder transparency and inadequate protection of minority and foreign shareholders, a paradigm more familiar in Asia, Latin America and some east European nations. In such transitional and developing economies there is a need to build, nurture and grow supporting institutions such as a strong and efficient capital market regulator and judiciary to enforce contracts or protect property rights.

From the Angle of Developed Versus Developing Countries

The concept of corporate governance can also be viewed from the context of economic development achieved by countries. While the principles underlying the concept are the same and there is no question of the norms governing it being different, the evolution of the systems and procedures that are required to implement it are at varying degrees of maturity. The earlier definitions quoted assume that in all societies an efficient and functioning legal system is in place, which is unfortunately, not so.

Figure 1.3 The “control model” governance chain (more common in Asia, Latin America, parts of Europe)

The Anglo-American, German, Japanese and other mature and developed economies have all well-functioning market systems and highly developed legal institutions, although there are considerable differences between them as there are in other features of democracy. In fact, it is these well-developed and mature institutions that have played a significant role in ushering in faster economic development of these countries. Therefore, in such economies, proper checks and balances exist to ensure good corporate behaviour. Even if any aberration occurs and corporate misdemeanour is noticed, quick remedial action can be taken to arrest the spread of such virus throughout the system, as was promptly done in the US by the Bush administration through the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the wake of corporate failures in 2002.

In the context of developed societies, the essence of corporate governance as expressed in the words of Patricia A. Nodoushani and Omid Nodoushani is as follows: “It is a relationship among various participants in determining the direction and performance of a corporation. However, corporate governance goes beyond the simple concept of who is in charge and who has the power. Chief among its goals are improving shareholder value and supporting a continuing commitment to growth.”

Providing the foundation to this more “traditional” view of corporate governance are three basic assumptions: Primacy of the shareholder; diversity of the shareholder group; and the maximisation of shareholder wealth as a fundamental raison d’être of a company.5 This view is consistent with both the Anglo-American system and the Continental European or German systems. Yet another crisp definition was from the former President of World Bank, J. Wolfensohn, who expressed the view that “corporate governance is about promoting corporate fairness, transparency and accountability.”6

In such a scenario, in the absence of mature supporting institutions, governance practices tend to be designed as more ad hoc to suit the needs of controlling or influencing the shareholders. According to McKinsey, “the Market Model is a natural goal or target for any reform process of developing or transition economies which will however require fundamental institutional reform” to usher in material changes in the functioning of corporates.

According to some other experts: “Corporate governance means doing everything better to improve relations between companies and their shareholders; to improve the quality of outside directors; to encourage people to think of long-term relations; information needs of all stakeholders are met and to ensure that executive management is monitored properly in the interest of shareholders.”

Sir Adrian Cadbury, chairman of the Cadbury Committee, defined the concept thus: “Corporate governance is defined as holding the balance between economic and social goals and also between individual and communal goals. The governance framework is there to encourage the efficient use of resources and equally to require accountability for the stewardship of those resources. The aim is to align as nearly as possible the interest of individuals, corporations and society. The incentive to corporations is to achieve their corporate aims and to attract investment. The incentive for states is to strengthen their economies and discourage fraud and mismanagement.”7

Defining corporate governance is not an easy task. It varies according to the sensitivity of the analyst, the context of the degree of development of the country to which it is referred and the different standpoints of the analysts, though there is an underlying unity in all these definitions. The Cadbury Report was a forerunner and made a significant contribution to the understanding of the concept.

Experts at the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have defined corporate governance as “the system by which business corporations are directed and controlled.” According to them, “the corporate governance structure specifies the distribution of rights and responsibilities among different participants in the corporation, such as, the Board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders, and spells out the rules and procedures for making decisions on corporate affairs” (OECD, April 1999). By doing this, it provides the structure through which the company objectives are set, and also provides the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance. OECD’s definition, incidentally is consistent with the one presented by Cadbury Committee.

All these definitions which are shareholder-centric capture some of the most important concerns of governments in particular and the society in general. These are: (i) management accountability, (ii) providing adequate investments to management, (iii) disciplining and replacement of bad management, (iv) enhancing corporate performance, (v) transparency, (vi) shareholder activism, (vii) investor protection, (viii) improving access to capital markets, (ix) promoting long-term investment, and (x) encouraging innovation.

All these traditional views reflect the necessity of corporate governance for improved performance of corporates themselves. However, there is a growing school of thought that maintains that this traditional theory does not go far enough. Good governance is critical not only for the success or failure of companies, but also for industries and economies as well. Besides, there is a need to extend the concept of governance to corporates of developing and transitional economies and standardise it to accommodate “well-entrenched” local and regional customs, traditions and business practices, which may be very different from what are obtained in advanced societies.

Of late, corporate governance has become the cynosure of all issues connected with corporations. National business communities are gradually realising the fact that there is no substitute for getting the basic business and management systems in place in order to be competitive in the global market and to attract investment.

From the standpoint of developing economies and transition societies, ensuring corporate governance becomes difficult in the absence of a well-developed corporate culture, capital market, money market, regulatory systems, well-defined and suitable public policies, proactive governments, well-informed stakeholders and presence of corruption, bribery, discrimination and a culture of accepting misgovernance, fraud and corporate misdemenour as part of human frailities. This has been amply demonstrated in the manner in which corporates have been run in developing countries by all-pervasive family-owned concerns. Shareholders, on the other hand, have remained scattered, mute and often oblige managements and pass resolutions without a murmur for the meagre dividends and petty gifts. In such a scenario, developing strong and powerful regulatory institutions, legal structures and evolving healthy precedence is of great importance.

Corporate governance systems depend upon a set of institutions (laws, regulations, contracts, and norms) that create self-governing firms as the central element of a competitive market economy. These institutions ensure that the internal corporate governance procedures adopted by firms are enforced and that management is responsible to owners (shareholders) and other stakeholders.8 As John D. Sullivan asserts: “In developing economies one must look to supporting institutions—for example, shoring up weak judicial and legal systems in order to enforce contracts and protect property rights in a better way.”9 This need for an institutional arrangement being the sine qua non for adopting better corporate governance practices is underlined in the following definition: “Corporate governance is not just corporate management; it is something much broader to include a fair, efficient and transparent administration to meet certain well-defined objectives. It is a system of structuring, operating and controlling a company with a view to achieving long-term strategic goals to satisfy shareholders, creditors, employees, customers and suppliers and to comply with the legal and regulatory requirements, apart from meeting environmental and local community needs. When it is practised under a well-laid out system, it leads to the building of a legal, commercial and institutional framework and demarcate the boundaries within which these functions are performed.”10

Definitions point to the fact that corporate governance systems depend upon a set of institutions such as laws, regulations, contracts and norms that create self-governing firms as the central element of a competitive market economy. These institutions ensure that the internal corporate governance procedures adopted by firms are enforced and that managements are responsible to owners and other stakeholders.

A critical factor in corporate governance is the inherent need to accept it, and to get acclimatised to, change with its fast phase and unpredictability in a market-driven global economy, even while getting even with cut-throat competition at all levels. Every country wants its corporates to flourish and grow, provide wealth and welfare to its people, enhance standards of living and ensure social cohesion to the extent feasible.

But these concerns are not limited to developing countries and transition societies alone. There is a global trend towards strengthening corporate governance. For example, in recent years, the Cadbury Committee in the United Kingdom, the Vienot Commission in France, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have all issued new guidelines. In the United States, there is mounting concern over the “independence” of independent audits as witnessed in the recent publicity surrounding violations of rules prohibiting auditors to invest in companies that they audit. In all of these cases, the underlying concerns centre around ways to accomplish the core values of corporate governance including transparency, accountability and building values.11

In this context, it is refreshing as well as interesting to note another definition of corporate governance: “Some commentators take too narrow a view, and say it (corporate governance) is the fancy term for the way in which directors and auditors handle their responsibilities towards shareholders. Others use the expression as if it is synonymous with shareholders’ democracy. Corporate governance is a topic recently conceived, as yet ill-defined, consequently blurred at the edges… Corporate governance as a subject, as an objective, or as a regime to be followed for the good of shareholders, employees, customers, bankers, and indeed for the reputation and standing of our nation and its economy.”

Narrow Versus Broad Perceptions of Corporate Governance

Corporate governance can also be defined from a very narrow perception to a broad manner. According to an article that appeared in Financial Times in 1997: “Corporate governance… is defined narrowly as the relationship of a company to its shareholders or, more broadly, as its relationship to society.”

According to an article that appeared in Financial Times in 1997, “Corporate governance is defined narrowly as the relationship of a company with its shareholders or, more broadly, as its relationship with society.” Thus, the concept covers a vast canvas and cannot be put into one straitjacket.

The earliest definition of corporate governance in its narrow sense is from the Economist and Nobel Laureate, Milton Friedman. According to him, “corporate governance is to conduct the business in accordance with the owner’s or shareholders’ desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible, while conforming to the basic rules of the society embodied in law and local customs.” This definition is based on the economic concept of market value maximisation that underpins shareholder capitalism. In the present day context, Friedman’s definition appears narrow in scope. In this narrow sense, corporate governance can be viewed as a set of arrangements internal to the corporation that define the relationship between the owners and managers of the corporation. For instance, Monks and Minow12 define corporate governance as “the relationship among various participants in determining the direction and performance of corporations. The primary participants are: (1) the shareholders, (2) the management, and (3) the board of directors.”13

The World Bank defines corporate governance from two different perspectives. From the standpoint of a corporation, the emphasis is placed on the relations between the owners, management, board and other stakeholders (the employees, customers, suppliers, investors and communities). Major significance in corporate governance in this narrow perspective is given to the board of directors and its ability to attain long-term, sustained value by balancing these interests. From a public policy perspective, corporate governance refers to providing for the survival, growth and development of the company, and at the same time, its accountability in the exercise of power and control over companies. The role of public policy is to discipline companies and, at the same time, to stimulate them to minimise differences between private and social interests.14 The OECD also offers a broader definition: “…Corporate governance refers to the private and public institutions, including laws, regulations and accepted business practices, which together govern the relationship in a market economy, between corporate managers and entrepreneurs (corporate insiders) on one hand, and those who invest resources in corporations, on the other.”15

From all the above definitions, any discerning reader can understand that good corporate governance is a desideratum to the growth and development of enterprises worldwide. To attain sustainable economic growth, the economy should boast of a growing enterprise sector which is, inter alia responsible, accountable, transparent and fair not only to its shareholders, but also to the entire groups of stakeholders. These characteristics of good corporate governance are now recognised as a sine qua non for access to, and development of, financial markets, and are being increasingly demanded by both international and domestic investors.

In the case of transition economies which are eager to convert their command economies to market-driven economies, it is improved corporate performance that will justify and accelerate their efforts to reach their goal. In the case of India too, the government found implementation of delicensing, deregulation and liberalisation relatively “easy going” because of the improved performance of the corporate sector in the wake of the new economic policy initiated in and after 1991, which in turn, boosted the growth of the country’s national income, in the aftermath of the changed strategies in economic policy.

Ensuring better corporate governance practices in the country’s mega corporations will result in boosting investors’ confidence so that they can confidently commit their funds to them. Having a transparent and fair system to govern markets, equitable treatment of all stakeholders and an opportunity to enterprises to prove their worth in competitive markets are all very important to the successful development of an economy. And in this scenario, corporate democracy should go hand-in-hand with political democracy.

Perceptional Differences in Definitions

We have seen several definitions of corporate governance and any intelligent reader would not have failed to note the fact that even while all of them emphasise the importance of ensuring good corporate governance practices for the good of the economy and the nation, there is a perceptible difference in the emphasis they lay in terms of objectives, goals and the means and tools to achieve and realise it. In this context, it will be appropriate to recall the contention of many writers of the history of economic thought. Having gone through the chequered history and development of economic thought with their profound impact on the policy formulations and functioning of economies world-wide, they come to the inevitable conclusion that economic doctrines—though they appear to be permanent and inexorable—reflect the conditions of the times in which they are enunciated; so also the contexts and the situations in which they are to be tested or to be put into practice. Lest one is tempted to jump to the conclusion that such economic doctrines have no scientific relevance, one should be clear in one’s mind that economics being a social science studying human behaviour that can not be put into one strait-jacket, can hardly have inflexible and exact doctrines like physics or mathematics.

In the several definitions of corporate governance that are available any intelligent reader would not have failed to note the fact that even while all of them emphasise the importance of ensuring good corporate governance practices for the good of the economy and the nation, there is a perceptible difference in the emphasis they lay in terms of objectives, goals, means and tools to achieve and realise it.

Therefore, corporate governance which reflects a practical field of economics too has definitions that lay varying degree of emphasis on time, context and the dimensions of corporate governance issues. According to some economists: “Corporate governance is a field in economics that investigates how to secure/motivate efficient management of corporations by the use of incentive mechanisms, such as contracts, organisational designs and legislation. This is often limited to the question of improving finance performance, for example, how the corporate owners can secure/motivate that the corporate managers will deliver a competitive rate of return.”16

Thus, in today’s world different governance practices exist in different markets reflecting the business reality. But there is a common view that the “natural goal” for all markets, be they developed or developing, should be essentially the same. But even though there is common goal, writers on the topic also come to the conclusion that “One Size Does Not Fit All.” For example, Mayer is of the view that “governance is more than shareholder/management alignment; it is about who is in control, for how long and over what critical important corporate activities.” Other commentators argue that new economy companies’ governance structures should adopt themselves rapidly to the fast-moving changes in control, while this adoption may be slow in old economy companies. It is, therefore, important that governance structures and practices should be tailored to meet appropriate requirements and needs.

There are many writers who hold the view, as Mayer does, that governance is moving in a direction that encompasses corporate strategy as a key element. To Mayer, “corporate governance is not… solely concerned with the efficiency with which companies are operated in the interests of shareholders. It is also intimately related to company strategy and life cycle development.”

There are writers who would want corporate governance to include management discipline (including financial discipline), business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and stakeholder participation in the decision-making processes. It is also being presumed that corporates have a responsibility to promote sustainable economic development of the countries in which they operate. In this era of globalisation, it is being increasingly realised that instituting corporate governance is not only a means to survive in today’s competitive world, but a good strategy to prosper.

Governance Is More Than Just Board Processes and Procedures

To most of us, corporate governance is just a set of codes and guidelines to be practised diligently by companies. We have the Cadbury Code and the CII Code of Desirable Corporate Governance. These codes generally enjoin corporations to ensure changes in their Board structures and procedures with a view to making the company more accountable to shareholders. To achieve such an objective, they would recommend increasing the number of independent directors on boards and not to have one person acting both as the chairman and CEO, and to introduce committees for specific purposes such as the audit committee and remuneration committee.

Corporate governance is generally perceived as a set of codes and guidelines to be followed by companies. But governance is more than just board processes and procedures. It involves relationships between a company’s management, its board, shareholders and other stakeholders.

However, “governance is more than just Board processes and procedures. It involves the full set of relationships between a company’s management, its Board, its shareholders and its other stakeholders, such as its employees and the community in which it is located. The quality of governance is directly linked to the policy framework. In the 21st Century, stability and prosperity will depend on the strengthening of capital markets and the creation of strong corporate governance systems.”17 In such a scheme of things, therefore, governments play a crucial role in making the legal, institutional and regulatory framework within which governance systems are kept in place. The efficiency or otherwise of the governance system will directly depend on the framework conditions, which would include legal rights of shareholders and how these are protected when violated by managements.

Writers on the theme of quality of governance link it to the efficiency or otherwise of the economies. Poor governance, for instance, can wreck havoc on the performance of national economies, which in turn, will upset global financial stability. The financial crises in Russia and Asia had created ripples that affected not only the countries in their regions, but the entire world’s economy. Poor governance undermines investor confidence in the markets and holds the whole financial system hostage. This is the reason why even in advanced countries like the US, UK, France, Germany, Sweden and Australia, important long-term efforts have been initiated in the sphere of company law, mergers and acquisitions by companies.

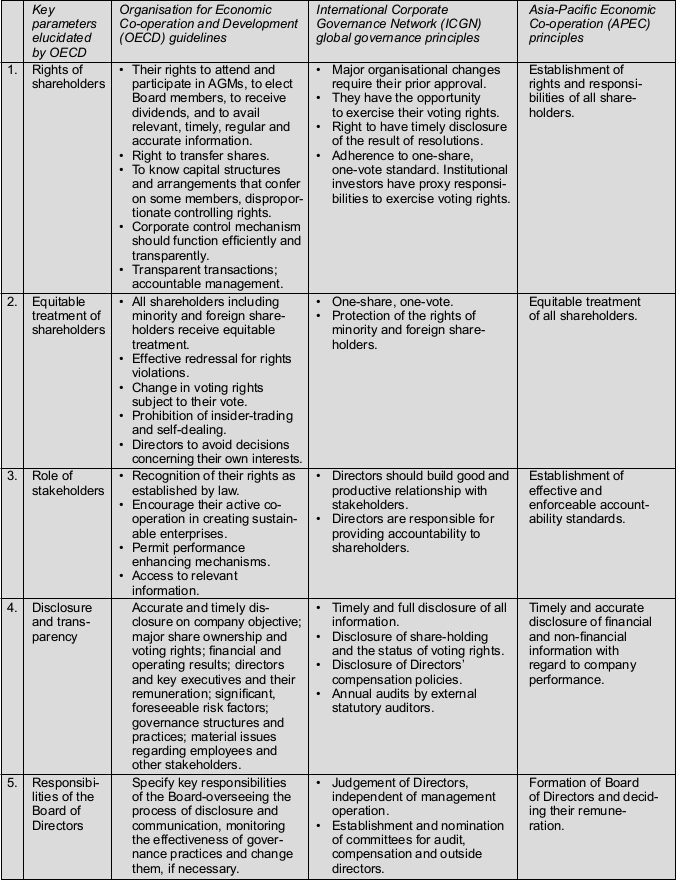

All these broader visions of corporate governance and the consequent improvements that have been effected in the systems, procedures and the frameworks are the direct outcome of the increasing public awareness about the necessity to have better governance practices. In this effort, not only governments are involved, but also world-level organisations such as the World Bank, OECD, and Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC). The OECD, for instance, had elaborated the corporate governance system which had been adopted by its member governments.

The OECD has emphasised the following requirements of corporate governance:

- Rights of shareholders: The rights of shareholders which have been stressed as important for ensuring better corporate governance by all writers and organisations including the World Bank and APEC, include secure ownership of their shares, voting rights, the right to full disclosure of information, participation in decisions on sale or any change in corporate assets (including mergers) and new share issues. Shareholders have the right to know the capital structures of their corporation and arrangements that enable certain shareholders to obtain control disproportionate to their holding. All transactions should be at transparent prices and under fair conditions. Anti-takeover devices should not be used to shield management from accountability. Institutional shareholders should consider the costs and benefits of exercising their voting rights.

- Equitable treatment of shareholders: The OECD and other organisations such as APEC have stressed the point that all shareholders including minority and foreign shareholders should get equitable treatment. All shareholders should have equal opportunity for redressal of their grievances and violation of their rights. Shareholders should not face undue difficulties in exercising their voting rights. Any change in their voting rights should be subject to a vote by shareholders. Insider trading and abusive self-dealing that are repugnant to the principle of equitable treatment of shareholders should be prohibited. Directors should disclose any material interests regarding transactions. They should avoid situations involving conflict of interest while making decisions. Interested directors should not participate in deliberations leading to decisions that concern them.

- Role of stakeholders in corporate governance: The OECD guidelines as also others on the subject of corporate governance recognise the fact that there are other stakeholders in corporations apart from shareholders. Apart from dealers, consumers and the government who constitute the stakeholders’ group, there are others too who ought to be considered. Banks, bondholders and workers, for example, are important stakeholders in the way in which companies perform and make decisions. Corporate governance framework should, apart from recognising the rights of shareholders, allow employee representation on board of directors, profit sharing, creditors’ involvement in insolvency proceedings etc. For an active stakeholder participation, it should be ensured that they have access to relevant information.

- Disclosure and transparency: The OECD lays down a number of provisions for the disclosure and dissemination of key information about the company to all those entitled for such information. These may range from company objective to financial details, operating results, governance structure and policies, the board of directors, their remuneration, significant foreseeable risk factors and material issues regarding employees and other stakeholders. The OECD guidelines also spell out that annual audits should be performed by independent auditors in accordance with high quality standards. Like the OECD, the APEC also provides guidelines on the establishment of effective and enforceable accountability standards and timely and accurate disclosure of financial and non-financial information regarding company performance. Moreover, in the administration and management of a company, there may be several grey areas that baffle managers as to which course of action must be pursued to be on the right side of law. In such a piquant situation, they are expected to disclose their options to stakeholders. “When in doubt, disclose” is the ideal guideline one must follow.

- Responsibilities of the board: The OECD guidelines explain in detail the functions of the Board in protecting the company, its shareholders and its other stakeholders. These functions would include concerns about corporate strategy, risk, executive compensation and performance, accounting and reporting systems, monitoring effectiveness and changing them, if needed. APEC guidelines include establishment of rights and responsibilities of managers and directors.

Most worldwide organisations that strongly promote corporate governance as a means of enhancing economic growth of member nations such as World Bank, APEC and OECD insist on the inalienable rights of shareholders, equitable treatment to all of them, role of stakeholders in realising corporate governance, through disclosure, transparency and the boards’ responsibility in ensuring all these.

The OECD guidelines focus only on those governance issues which arise due to separation between ownership and control of capital. Though these have limited focus, they are comprehensive, especially with reference to voting rights of institutional shareholders and obligations of the Board to stakeholders. Though the APEC principles too reiterate them, they give foremost importance to disclosures. Again, instead of rights of shareholders, they reiterate the rights and also of the responsibilities of shareholders, managers and directors. To them, establishment of accountability standards is a separate principle by itself.

To conclude, most of the earlier definitions of corporate governance centre around issues and problems arising out of the separation between ownership and control of capital, such as rights of shareholders, equitable treatment of all shareholders including minorities, foreigners and other stakeholders, disclosure and transparency, and the responsibilities of the board of directors. Later day commentators on the topic stress the importance of corporate governance covering a wider spectrum of policies and procedures encompassing management disciplines, stakeholder participation in decision making processes, social responsibility and corporation’s contribution to sustainable development. There is now a definite emphasis on the quality of governance which is imperative and vital to achieve and realise all these policies. Moreover, it is necessary that we have to have different hats to fit different heads. One Size Does Not Fit All. The Broad objectives and principles of corporate governance may be the same to all societies, but when it comes to applying them to individual countries we have to reckon the peculiar features, socio-cultural characteristics, the history of its people, their value systems, economic system, political set-up, stage and maturity of development and even literacy rates. All these factors have an impact on both political and corporate governance systems. Superimposing the governance systems and procedures that are effective in mature Western democracies on transition economies will be inappropriate, ineffective and may even be inimical to the interests of the people these are intended to serve.

A comparative study of corporate governance guidelines issued by three international organisations, namely, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Corporate Governance Network and the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation which fairly represent the thinking and perceptions of people on several governance issues of corporates is given on the next page.

A Historical Perspective of Corporate Governance

From a Narrow to a Broader Vision

As we have observed earlier, corporate governance has focussed traditionally on the problem of the separation of ownership by shareholders and control by management. But with the passage of time, experiences gained from historical developments of corporate misdemeanour and with the impact of a growing visions of society, we have come to recognise increasingly a broader framework of corporate governance. It is now accepted that firms should respond to the expectations of more categories of stakeholders which include employees, consumers, large institutional investors, government and the society as a whole. These diverse interests are to be harmonised and accommodated. Firms can achieve long-run value maximisation only if they respond to the expectations of these increasingly large number of stakeholders. In recent years, externalities such as product safety, job safety, and environmental impacts have increased the importance and significance of better governance of corporations to achieve these ends. Still more additions to the wide range of corporate governance practices include as indicated earlier business ethics, social responsibility, management discipline, corporate strategy, life-cycle development, stakeholder participation in the decision-making processes, and promotion of sustainable economic development. Nowadays commentators on the issue emphasise the importance of the quality of governance. All this growth in the perception of corporate governance from the very narrow definition of Milton Friedman (to conduct the business purely in accordance with shareholders’ desires) to the very broad to include the entire society, has not been achieved in a short period. The evolution and development of corporate governance as an all-encompassing system of corporate behaviour with a great stake in sustainable development has an interesting and chequered history.

Corporate governance has focussed traditionally on the problem of the separation of ownership by shareholders and control by management. It is now accepted that firms should respond to the expectations of more categories of stakeholders. The wide range of corporate governance practices include business ethics, social responsibility, management discipline, corporate strategy, life-cycle development, stakeholder participation in the decision-making processes and promotion of sustainable economic development.

TABLE 1.1 Corporate governance guidelines—a comparative study

Source: OECD, ICGN, APEC and Cal PERS Web sites.

The Growth of Modern Ideas of Corporate Governance from the USA

The seeds of modern ideas of corporate governance were sown by the Watergate scandal during the Nixon presidency in the US. Subsequent investigations on the scandal revealed that the regulators and legislative bodies failed to control and stop several major corporations from making illegal political contributions and bribing government officials. The need to arrest such unhealthy trend was translated into the legislation of the Foreign and Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 in America that provides for the maintenance and review of systems of internal control in an establishment. In the same year, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed mandatory reporting on internal financial controls. In 1985, a series of high profile business failures rocked the US which included the collapse of Savings and Loan. With a view to identifying the main causes of misrepresentation in financial reports and to recommend ways of reducing such incidences, the government appointed the Treadway Commission. Its report published in 1987 highlighted the need for a proper control environment, independent audit committees and an objective Internal Audit System. The Treadway Report underlined the need for published reports on the effectiveness of internal control and advised the sponsoring organisations to develop an integrated set of internal control criteria to enable corporations improve their control mechanisms. As a result of this recommendation, the Committee of Sponsoring Organisations (COSO) came into being. COSO’s Report in 1992 stipulated a control framework for the orderly functioning of corporations.

The seeds of modern ideas of corporate governance were probably sown by the Watergate scandal during the Nixon presidency in the US. Subsequent investigations on the scandal revealed that the regulators and legislative bodies failed to control and stop several major corporations from making illegal political contributions and bribing government officials. It also paved the way for stiffer legislations.

England Catches Up

Even while these developments in the US stirred a healthy debate in the UK, a series of corporate scams and collapses in that country took place in the late 1980s and early 1990s which worried banks and investors about their investments and led the government in the UK to realise the inefficacy of the existing legislation and self-regulation. Famous corporations such as Polly Peck, Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), British & Commonwealth and Robert Maxwell’s Mirror Group International collapsed like a pack of cards. Illustrious business enterprises, which witnessed spectacular growth in boom time became disastrous failures later due to poor management and lack of effective control.

The Cadbury Committee

When it was realised in England that the existing rules and regulations were not adequate to curb unlawful and unfair practices of corporates so as to protect the unwary investors, it was thought necessary to look at the issues involved afresh and look for remedial measures. It was with this view a committee under the chairmanship of Sir Adrian Cadbury was appointed by the London Stock Exchange in 1991. This Cadbury Committee, consisting of representatives drawn from the echelons of British industry was assigned the task of drafting a code of practices to assist corporations in England in defining and applying internal controls to limit their exposure to financial loss, from whatever cause it arose.

The objective of the committee was “to help raise the standards of corporate governance and the level of confidence in financial reporting and auditing by setting out clearly what it sees as the respective responsibilities of those involved and what it believes is expected of them.” The Cadbury Committee, in a commendable pioneering effort, investigated extensively the accountability of the board of directors to shareholders and to the society. The committee submitted its report along with the “Code of Best Practices” in December 1992. In its globally well received report, the committee elaborated the methods of governance needed to achieve a balance between the essential powers of the board of directors and their proper accountability. Though the recommendations of the committee were not mandatory in character, the companies listed on the London Stock Exchange were enjoined to state explicitly in their accounts, whether or not the code has been followed by them, and if not complied with, were advised to explain the reasons for non-compliance.

The Cadbury Code of Best Practices had recommendations which were in the nature of guidelines relating to the board of directors, non-executive directors and those on reporting and control. These recommendations are given in Chapter 3: “Landmarks in the Emergence of Corporate Governance.”

In England, Sir Adrian Cadbury was entrusted in 1991, by the London Stock Exchange, with the task of drafting a code of practices to assist corporations in defining and applying internal controls to limit their exposure to financial loss. The Cadbury Committee investigated extensively the accountability of the board of directors to shareholders and to the society. The committee that submitted its report along with the “Code of Best Practices” in December 1992 elaborated the methods of governance needed to achieve a balance between the essential powers of the board and their proper accountability.

The Aftermath of the Cadbury Report

The Cadbury Committee’ s Report, especially its recommendations concealed in the Code of Best Practices, shocked the corporate world in Britain and elsewhere. Its most revolutionary recommendations reverberated several transformatory changes that were to be incorporated in the corporate sector everywhere and its ramifications vibrated not only in the advanced countries of the West, but also could be heard in emerging and transition economies like those of Russia, India and those in South East Asia. The most controversial of the Cadbury’s recommendations was the one that required that the “directors should report on the effectiveness of a company’s system of internal control.” It was the extension of control beyond the financial matters that caused the controversy.

After five years of the publication of the Cadbury Report, public confidence in corporates in England was again shaken by further scandals. To deal with the situation, a “Committee on Corporate Governance” headed by Ron Hampel was constituted with a brief to keep up the momentum by assessing the impact of Cadbury Report and developing further guidelines. The final report of the Hampel Committee submitted in 1998 contained some important and progressive guidelines, especially the extension of directors’ responsibilities to “all relevant control objectives including business risk assessment and minimising the risk of fraud.” Earlier, another Committee headed by Greenbury to address the issue of directors’ remuneration submitted its Report in 1995. An amalgam of all these codes known as the Combined Code was subsequently derived. This Combined Code is appended to the listing rules of the London Stock Exchange and its compliance was made mandatory for all listed companies in the United Kingdom.

The Combined Code stipulated, inter alia, that the boards should maintain a sound system of internal control to safeguard shareholders’ investment and the company’s assets. Further, the directors should, conduct a review of the effectiveness of the group’s system of internal control and report to shareholders at least once a year that they have done so. The review should cover all controls, including financial, operational and compliance and risk management.

The developments with regard to corporate governance led to the publication of Turnbull Guidance in September 1999, which required the board of directors to confirm that there was an ongoing process for identifying, evaluating and managing key business risks. Shareholders, after all, are entitled to ask if all the significant risks had been reviewed (and presumably appropriate actions taken to mitigate them) and why was a wealth-destroying event not anticipated and acted upon?

It was also found that the one common factor behind past failures of corporates was the lack of effective Risk Management. Risk Management subsequently grew in importance and is now seen as highly crucial to the achievement of business objectives by corporates.

It was clear, therefore, that boards of directors are not only responsible but also needed guidance not just for reviewing the effectiveness of internal controls but also for providing assurance that all the significant risks have been reviewed. Furthermore, assurance was also required that the risks had been managed and an embedded risk management process was in place. In many companies, this challenge was being passed on to the Internal Audit function.

Corporate Governance in the Banking Sector

Around this time, some bank failures in the West underlined the necessity of close monitoring of the banking system. Weakness in the banking system of a country can threaten the financial stability, both within the country and globally. The need to improve the strength of financial systems has attracted growing international concern. A communication issued at the close of the Lyon G-7 Summit in June 1996 called for action in this vital area. Several official bodies including the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision established by the Central Bank Governors of the Group of Ten Countries in 1975, the Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have recently been examining ways and means to strengthen financial stability throughout the world.

Some bank failures in the West underlined the necessity of close monitoring of the banking system. Weakness in the banking system of a country can threaten the financial stability, both within the country and globally. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has been working in this field for many years, both directly and through its many contacts with banking supervisors in every part of the world.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has been working in this field for many years, both directly and through its many contacts with banking supervisors in every part of the world.

Revival of Corporate Governance Issues in the New Millennium

As the stock market began to decline in the United States in early 2000, a number of thus far highly regarded companies began to collapse. Most dramatic was the demise of Enron. Serious problems were also reported at WorldCom, Adelphia, Global Crossing, Dynegy, Sunbeam, and Tyco. The revelations gave rise to anguished complaints of corruption, fraud, deception, insider trading and self-dealing at major corporations, which only months ago, looked invincible and almost infallible. Further research revealed that these examples of types of corporate fraud represented only a small sample of the murky goings on in hundreds of corporations. Between the period 2000 and 2002, the revelations of corporate fraud in the US were of such magnitude and inflicted such damage on investors’ that company reputations were irreparably destroyed and investors confidence dipped to a new low. Declining stock prices and erosion of billions of dollars of investors had severe and widespread impacts. The fraud and self-dealing revelations resulted in investigations by the US Congress. the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and the State Attorney General in New York. All these enquiries and the conclusions put their teeth in a comprehensive Act. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOA) was enacted into a law on 30 July 2002.

It is said that eternal vigilance is the price of freedom. Such is also the price investors have to pay for ensuring corporate governance. Complacence and undue faith and trust in corporate managements have resulted in huge and unbearable losses of investors’ hard-earned money. The history of corporate governance gives us an unforgettable lesson that vigilance and a continuing effort at building and strengthening it alone will give the investors the safety net they require.

Issues in Corporate Governance

Corporate governance has been defined in different ways by different writers and organisations. Some define it in a narrow perspective to include in it only the shareholders, while others want it to address the concerns of all stakeholders. Some talk about corporate governance being an important instrument for a country to achieve sustainable economic development, while some others consider it as a corporate strategy to achieve a long tenure and a healthy image. To people in developing societies and transitional economies, it is a necessary incentive to usher in more powerful and vibrant institutions of control. To some, it provides another dimension to corporate ethics and social responsibility of business. Thus corporate governance has different meaning to different people. But to all, corporate governance is a means to an end, the end being long term shareholder, and more importantly, stakeholder value. Thus, all authorities on the subject are one in recognising the need for good corporate governance practices to achieve the end for which corporates are formed. They identify some governance issues being crucial and critical to achieve these objectives. These are:

Corporate governance conveys different meanings to different people. But to all, corporate governance is a means to an end, the end being long-term shareholder value, and more importantly, stakeholder value. Thus, all authorities on the subject are one in recognising the need for good corporate governance practices to achieve the end for which corporates are formed.

1. Distinguishing the roles of board and management: Constitutions of more and more companies stress and underline that the business is to be managed “by or under the direction of” the board. In such a practice, the responsibility for managing the business is delegated by the board to the CEO, who in turn delegates the responsibility to other senior executives. Thus, the board occupies a key position between the shareholders (owners) and the company’s management (day-to-day managers of the company’s resources). As per this arrangement, the board of a listed company has the following functions:

- Select, decide the remuneration and evaluate on a regular basis, and when necessary, change the CEO.

- Oversee (not directly, but indirectly) the conduct of the company’s business to evaluate whether or not it is being correctly managed.

- Review and, where necessary, approve the company’s financial objectives and major corporate plans and objectives.

- Render advice and counsel top management including the Board of directors.

- Identify and recommend candidates to shareholders for electing them to the board of directors.

- Review the adequacy of systems to comply with all applicable laws and regulations.

- All other functions required by law to be performed.

2. Composition of the board and related issues: A board of directors is a “committee elected by the shareholders of a limited company to be responsible for the policy of the company. Sometimes, full-time functional directors are appointed, each being responsible for some particular branch of the firm’s work.”18

The composition of board of directors refers to the number of directors of different kinds that participate in the work of the board. Over a period of time there has been a change as to the number and proportion of different types of directors in the board of a limited company. Figure 1.4 illustrates the usual composition of the board in recent times in most of the countries.

The SEBI-appointed Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee’s Report defined the composition of the Board thus: “The Board of Directors of a company shall have an optimum combination of executive and non-executive directors with not less than 50 per cent of the board of directors to be non-executive directors. The number of independent directors would depend whether the chairman is executive or non-executive. In case of a non-executive chairman, at least one-third of the board should comprise independent directors and in case of executive chairman, at least half of the board should be independent directors.”19

Figure 1.4 Types of Directors

As shown in Figure 1.4, an executive director is one who is an executive of the company and also a member of the board of directors, while a non-executive director has no separate employment relationship with the company. Independent non-executive directors are those directors on the board who are free from any business or other relationship which could materially interfere with the exercise of their independent judgement in the process of decision-making as a member of the board. An affiliated director or a nominee director is a non executive director who has some kind of independence, impairing relationship with the company or the company’s management. For example, the director may have links with a major supplier or customer of the company, or may be a partner in a professional firm that supplies services to the company, or may be a retired top management professional of the company.20

3. Separation of the roles of the CEO and chairperson: The composition of the board is a major issue in corporate governance as the board acts as a link between the shareholders and the management and its decisions affect the performance of the company. Professionalisation of family companies should commence with the composition of the board. All committees that studied governance practices all over the world, starting with the Cadbury Committee, have suggested various improvements in the composition of boards of companies.