Photographing Little Critters

Personally, I believe that plants, bushes, grasses, and trees in the landscape and the garden are living beings, and sentient. True, the kind of sentience is no doubt very different than ours, and the way time flows for a flower is probably very different than it does for us. My opinion remains that flowers and trees do at some level think and also communicate with one another, even if we don’t understand the mode of communication.

You may—or may not—agree with me about how the life force manifests in flora. But when it comes to living beings in a garden, there is little doubt that insects and other critters coexist in these realms with us. Some kinds of garden photography includes portraiture of these small denizens of our special places.

Getting Close

One of the biggest challenges with garden photography of little critters is getting close enough—both in terms of the telephoto so that your presence doesn’t scare the creature, and in terms of the magnification, so that you can enlarge interesting details. A telephoto-macro lens (see page 127) may be just what the doctor ordered if this kind of photography interests you.

When I first started photographing denizens as part of my garden photography, I learned that insects, hummingbirds, and other small flying critters tend to be somewhat obsessive-compulsive. I’m not really talking about a psychiatric diagnosis, just their habits.

Many are, as the saying goes, “creatures of habit.” Should you happen to disturb one of your diminutive models on its perch, it’s a very good tactic to expect it to return to the same place. Carry on, stay very still, and wait at least ten minutes. More than half the time, the winged little critter will return to exactly the same position and posture. This time around, since you are ready and the camera is already focused with the exposure set (hopefully!), you have a better chance of making your photograph.

Speaking of staying still, perhaps the best approach to getting close to small critters is to learn to meld with your environment. This means that you should avoid abrupt motions. Staying quiet is also important. Don’t listen to music with earbuds. Small garden critters have hearing that is far better than ours. Dress in colors that blend into the environment, perhaps in dark green or black for a shady area. In my experience, hummingbirds and butterflies seem to be happier around me in the sunshine when I am wearing a brightly colored Hawaiian shirt. I think perhaps I have become like a flower. But perhaps that’s just me!

Dragonfly Wing—After a rainy afternoon, the weather cleared. I went out to the garden to photograph water drops. I put my camera on my tripod, added a telephoto-macro lens (200mm on a 1.5 crop-factor sensor, for a focal-length equivalency of 300mm), then added an extension tube and a close-up filter, so I could get really close to the water drops. At its closest focus, this setup rendered results that were many magnifications of life-size.

As I was photographing, a dragonfly settled in my garden and was very still for a short while. Since I was already set up, I was able to make a close-up photo of the dragonfly’s wings, backlit by the late afternoon sun.

At this high magnification, the dragonfly’s wing reminds me of either an architectural construction or stained glass. It is truly a miracle of nature to see the well-wrought details in very small living things.

Nikon D300, 200mm macro, 36mm extension tube, +4 diopter close-up filter, 2 seconds at f/36 and ISO 320, tripod mounted.

Taking Off—In bright sunlight, I saw an attractive moth land on a Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia). Fortunately, my telephoto-macro lens was already on the camera, and I was able to take a quick photo at a fast shutter speed (1/1600 of a second) before the fickle, pollen-gathering moth took off again to visit another flower. I used a near-wide-open aperture (f/4.2) to create an image with low depth of field so that only the peripatetic moth was in focus.

Nikon D810, 200mm macro, 1/1600 of a second at f/4.2 and ISO 200, hand held.

There are a few small garden critters that are potentially dangerous. I don’t think most of us object very much to bees—unless one has an allergy—and the world’s gardens do depend on them. I, myself, think of bees as warm, furry, sweet creatures. But take a look at the wasp shown on page 338. This is definitely a creature built for war and offense, more than defense or self-protection. At high magnification as in my photo, the wasp is definitely an object of fear, as it should be. The very idea of this creature is to be as aggressive as possible, or at least look that way. The only reason we are, for the most part, not incredibly endangered has to do with scale and our relative sizes.

So, I have come to repeat to myself at times, “wingy, stingy—nope!” It’s not that I won’t photograph such creatures, but I would prefer to do so with common sense. Wasps and bees—for that matter, all cold-blooded creatures—are sluggish and not very dangerous when they are cold. Early in the morning is a good time to photograph a critter that might otherwise sting you.

Of course, a telephoto lens is also a good idea. With wingy-stingy creatures, perhaps the longer the better. If this concept of getting a macro photo of a toxic creature with lesser risk interests you, take a look at the probe macro lens described on page 299.

Red Dragonfly—One summer morning, I was playing in the garden with my kids. We looked around and all of a sudden noticed this attractive red dragonfly had landed on a dried stalk. I ran inside to my studio and grabbed my camera and a telephoto-macro lens. Fortunately, the dragonfly waited patiently for me and was still there. He didn’t respond, however, when I asked for a model release!

I quickly made a few hand-held exposures at a moderately-high ISO (ISO 640), which enabled me to use a relatively fast shutter speed (f/9), and still have enough depth of field so the dragonfly was in focus, with some nice bokeh in the background.

Nikon D300, 200mm macro, 1/320 of a second at f/9 and ISO 640, hand held.

Stopping Motion

One issue with winged creatures in the garden is learning how to work with motion. As I’ve suggested, habits of insects tend to repeat, so if you wait quietly, there is a chance of photographing your intended subject in repose in a location that the critter has previously occupied.

But watchful waiting may be neither possible nor desirable, for example, if the light is rapidly shifting, or when it is significantly windy. Furthermore, sometimes the best photograph of a garden critter shows that critter doing something, such as flying or sticking out its tongue like the hummingbird shown on page 337.

To stop the motion of a creature that is, well, in motion there are really only two practical approaches from a technical perspective:

- Use a fast enough shutter speed to stop the motion. How short the duration of time needs to be to “freeze” motion depends on a number of variables, including the speed and direction of the creature, distance from the creature, the focal length of the lens used (greater focal lengths require faster shutter speeds to not add motion blur), and the mount of the magnification (if the photograph is a macro). Boosting the shutter speed to “stop” motion may require compromises on the other two legs of the exposure triangle, for example, boosting the ISO, or using a more wide-open aperture (see page 85 for more about the exposure triangle).

- Use a high-speed strobe to stop the motion of the creature. In particular, a macro-high-speed strobe setup, like the one described on page 347, can work well for this. Note that when you light a subject using a flash, the effective duration of the exposure is not controlled by the length that the shutter is open. Rather, the effective duration is managed by the high-speed burst of light put out by the flash units. This can be so brief (about 1/10,000 of a second) as to be essentially instantaneous. While flash has the drawback of potentially scaring fauna, a well-designed flash arrangement, possibly using a blind, may be the only practical way to get great photos of certain kinds of high-speed subjects.

Focusing and Critters

When you are making a photo of a critter in motion, this may be a good place to use autofocus. Whether you are choosing the focus points in an autofocus setup or manually focusing, it’s worth thinking about where the focus should be.

Generally, focus with animals works the same way as in a human portrait. When you look at someone, the eyes are a “window” into the soul. That’s why making eye contact is so important. When you look into someone’s eyes, you may feel you know them. So when I am making portraits, I almost always focus on the eyes.

This holds true even when the eyes are insect-like and a bit beady. Apart from a garden-gnome sculpture, you probably won’t go wrong when focusing on a critter if you try for the eyes. Keep in mind that on a macro scale, even a critter’s eyes can have considerable depth. The best focus point is the pupil of the eye.

One technique that I have found hugely invaluable relies on the property of insects in the garden being creatures of habit, as I have previously mentioned. You can take advantage of this general characteristic by projecting where the creature is likely to return to, and pre-focusing on that spot. The pre-focus may not be exact, but it will often get you close and give you a good head start.

A great deal of insect photography in the garden is done with fairly-wide-open aperture and low depth of field. This means that focus is really critical to this kind of image making.

If garden critters are your thing, then it’s worth spending some time practicing focus when it comes to macro subjects in motion.

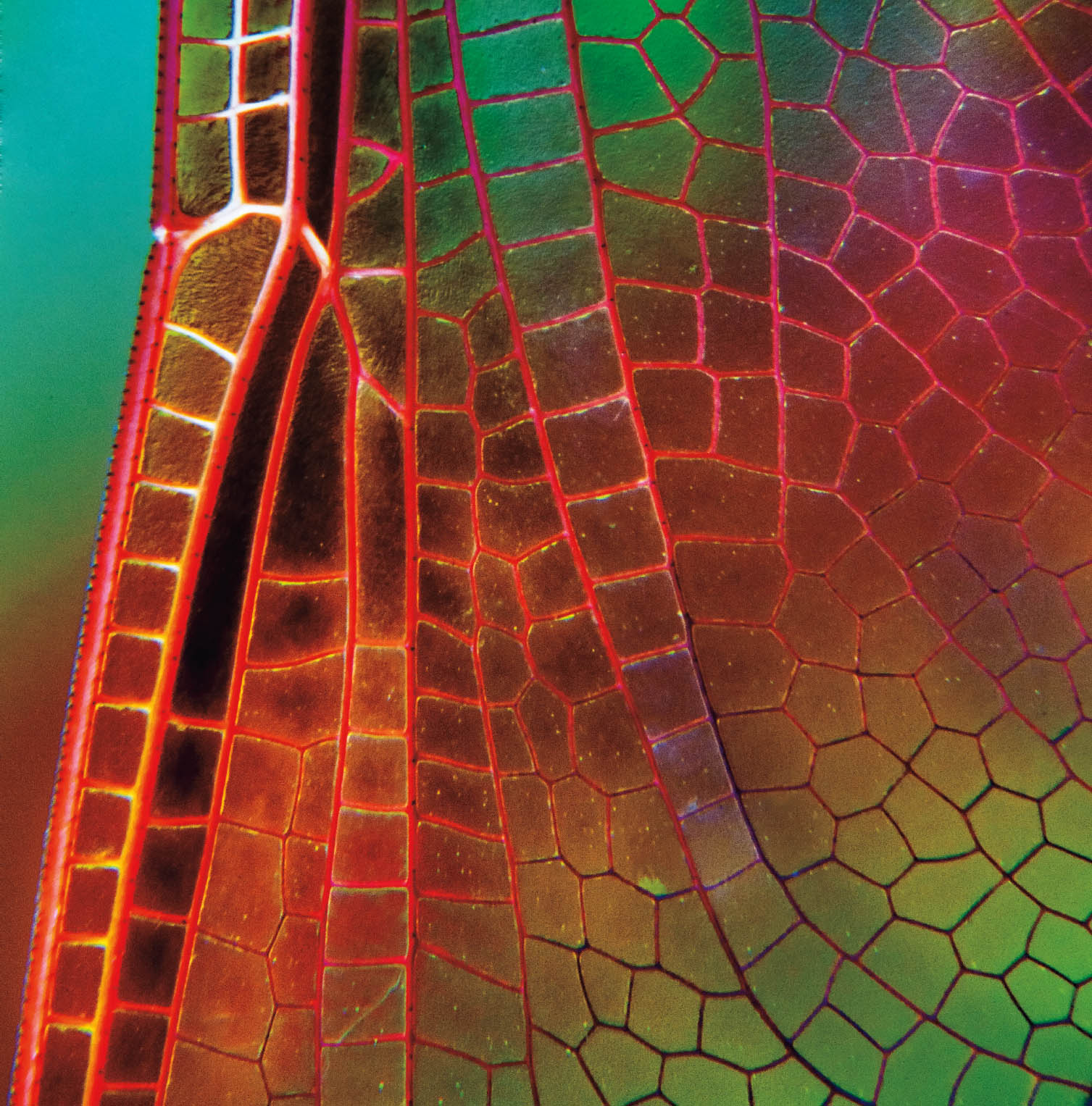

Dragonfly 4—Commissioned as part of a series of book cover photos for a publishing client, I started by photographing a specimen dragonfly on a light box. The actual specimen was nearly monochromatic without much variation in dynamic range, so I was able to make the photograph with a single capture.

This led to the problem that the assignment specification called for a colorful image, and what I had was nearly black and white. Photoshop to the rescue!

Using some of my favorite Photoshop tools—primarily cross-processing with LAB channel inversions and adjustments—I worked through many layers and versions to create the final dragonfly you see here. Ultimately, it was one of the accepted images in the series of book covers for my client.

Nikon D200, 200mm macro, 2 seconds at f/32 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

Bee the Light—Wandering around in nearby Blake Garden, I noticed a grist of bees buzzing and swarming around a bed of lowlying Bellflowers (Campanulas). I got down on my belly and aimed my Lensbaby macro up at one of the bees so that the flower behind the bee was spotlit and backlit by bright sunshine.

To take maximum advantage of the Lensbaby’s ability to “halo” light, I exposed wide open (at f/1.8) while focused and centered on the bee’s wings.

Nikon D850, 85mm Lensbaby Velvet macro, 1/1600 of a second at f/1.8 and ISO 64, hand held.

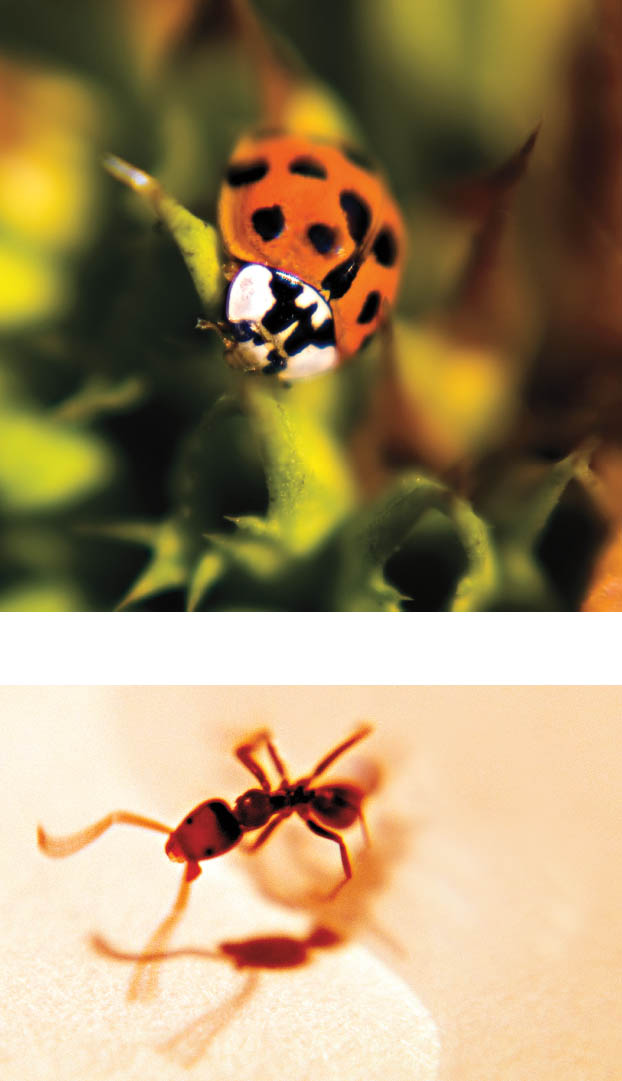

Ladybug—When my son Julian was little, I helped him plant “his” portion of the garden. Julian’s taste ran toward roses with thorns, and big, spiky succulent things. Toward the end of the season when Julian and I were out tending the garden, we saw this ladybug landing on the biggest, spikiest thing in Julian’s garden.

I ran inside, grabbed a camera with a Lensbaby and macro attachments, and made this close-up portrait of the ladybug.

A garden is healthy when there are many ladybugs, because ladybugs eat pests, such as aphids. One always has to applaud the economy of nature’s design in pesticide-free natural gardening. In this spirit, whenever I see a ladybug in a garden, I try to make its portrait.

Nikon D70, Lensbaby Composer with auxiliary close-up filter, 1/400 of a second, no aperture disk (wide-open) and ISO 200, hand held.

Lurker—Locusts are in the grasshopper family and have formed plagues since prehistory. In addition to the often-mentioned biblical “plague of locusts,” locusts are carved on ancient Egyptian tombs, and described in The Iliad and the Qur’an. Fundamentally, as grasshoppers these insects are harmless and solitary. However, under specific conditions—usually drought followed by rapid vegetation growth—serotonin released in their brains triggers a dramatic set of changes where the solitary insects become gregarious and migratory, unleashing the proverbial plague. A swarm of locusts can decimate and strip a field in minutes, and can powerfully fly from one agricultural area to another, causing multiple famines in human history.

Who knows what lurks in the fields and botanicals near us? I had no idea that this presumably harmless locust lurked within a flower in my garden until I trained my telephoto-macro lens on the flower.

Nikon D200, 200mm macro, 1/60 of a second at f/20 and ISO 100, hand held.

Eyes of Newt—This red-bellied newt (Taricha rivularis) is a salamander species native to the California coastal ranges. I found this little fellow near a grove of redwood trees in Tilden Park, not too far from my home. Sunning himself, he paused for a close-up portrait before ambling off on all four legs into the trees. By the way, the skin on this species of newt contains strong toxins, so handling him (even if I had been so inclined) would have been inadvisable.

Nikon D70, 200mm macro, 1/250 of a second at f/5.6 and ISO 200, hand held.

Froggy & Me—This frog held still for me for a brief moment next to a decorative pond at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden in Seal Harbor, Maine. After I made the exposure, froggy leapt back into his pond with a splash!

Nikon D850, 50mm Zeiss Makro-Planar, 1/1000 of a second at f/8 and ISO 800, hand held.

Hummingbird Tongue—Hummingbirds are native to the Americas and are the bird species of the smallest size (the bee hummingbird weighs less than two grams, or 0.07 ounces). They are called hummingbirds because of the humming sound created by their wings, which flap at a high frequency that is audible to humans. They hover in midair with wings flapping at rates that vary from about 12 to 80 beats a second. Their top speeds can reach an excess of 50 mph (80 km/h) in a dive.

Hummingbirds have the highest mass-specific metabolic rate of any warm-blooded animal. To conserve energy when there is no food or at night when they are not foraging, they go into torpor, which is a state similar to hibernation with a metabolic rate about 1/15 of normal. During the day, when there is food, hummingbirds are almost constantly eating, flitting from one food source to another.

Contrary to what you might expect, hummingbirds don’t suck nectar from flowers as if their tongues were straws. They lap flower nectar up repeatedly by flicking their tongues—which are very long in proportion to their bodies—in and out. This hummingbird-tongue action is kind of dog-like, and I never would have known about it if I hadn’t pointed my telephoto lens and snapped a photo when this hummingbird was in the process of beginning to lap at a flower.

Nikon D200, 70–200mm Nikkor zoom at 200mm with a 2X teleconverter for an effective focal length of 600mm on a 1.5 crop-factor camera, 1/80 of a second at f/5.6 and ISO 100, hand held.

Wasp—It was a cold spring morning and our furnace was out of order. When I got up in the morning and surveyed the living room, I found a mostly somnolent wasp slowly pacing across the ceiling.

Looking at this creature, it is an amazing fighting machine on its scale. I would not want to be a very small critter in its path. Surely, the wasp as a species is well weaponized.

So my takeaway from viewing the wasp on the ceiling is that a chill in the air helps when you want to photograph an aggressively armored creature. When it’s relatively cold, they move slowly enough for a long exposure (in this case 3/5 of a second), and are also not as fierce.

To make this photo, I hastily improvised a chair with cardboard box on top so I could reach the ceiling with my camera and tripod. Perched precariously on this rickety foundation, I dialed up my exposure and gently squeezed the shutter release.

Nikon D70, 105mm macro, 36mm extension tube, 0.6 seconds at f/32 and ISO 200, tripod mounted.

Dragonfly in the Garden—It rained heavily in the afternoon. After the rain stopped, I went out in near dusk to photograph water drops on an iris bed. I mounted my camera on the tripod with a telephoto-macro lens and an extension tube to photograph the flowers with water drops close-up.

Turning around, I saw this dragonfly almost close enough to touch. My motion spooked the critter and he flew off. Since garden creatures very often return to the same place multiple times, I got ready for the return of the dragonfly. I pointed my camera and lens right at the spot that he had occupied before, set the depth of field to an intermediate value (f/14) so the dragonfly would be in focus but the background would be slightly soft, stayed stock still, and waited.

After a few minutes, my friend the dragonfly returned, posed long enough for me to make the exposure, and then flew off again.

Nikon D300, 200mm macro, 36mm extension tube, 1/5 of a second at f/14 and ISO 320, tripod mounted.