Chapter 10

Cultivating Your Critical Writing Skills

In This Chapter

![]() Structuring your writing for clarity

Structuring your writing for clarity

![]() Knowing and addressing your audience

Knowing and addressing your audience

![]() Walking your readers through the issues

Walking your readers through the issues

Explanations exist; they have existed for all time; there is always a well-known solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong.

—HL Mencken (‘The Divine Afflatus’, New York Evening Mail, 1917)

This chapter is all about applying Critical Thinking skills where they belong best — in writing. You get an overview of how to write effectively and also an ‘inside view’, as I explain the sorts of things that help to make writing, especially academic writing, clear, concise and successful. In the process, you really get into the nuts and bolts of Critical Thinking.

In this chapter, you can find out how to structure your writing to make its points clearer as well as about the ‘who, what and where’ factors that are vital to guiding your arguments. I dish up some tasty tips on preparation and research, and describe how to home in quickly on the textual clues in writing — by being aware of the key terms and words.

Finally (and that's a straightforward textual clue to flag the end of these introductory paragraphs!), you have an opportunity to develop your argumentation skills by deconstructing a passage into its constituent, logical parts, and specifically, its intermediate conclusions. Intermediate whats? It sounds like jargon, I know, (indeed, it is jargon) but the concept is useful and intermediate conclusions matter. You can find out all about them in this chapter.

Structuring Your Thoughts on the Page

By definition, a solid structure provides support for your piece of writing and gives readers the best chance of grasping your point or argument. In this section I cover the basics, show how to handle evidence and how to make sure that you really answer the question in an exam or assignment. All sprinkled with some essential tips on structure from an expert in the Critical Writing field.

Indentifying the basics of structure

What are the ingredients of a well-structured piece of writing? Well, writing first things first is a great start.

Also, in the context of factual writing, revealing your position at the outset is more honest, because then readers can critically evaluate your arguments. For instance, if you're going to present an argument that Shakespeare was an Eskimo, say so early on and then readers can be duly sceptical of any incidental details your essay starts to dwell on regarding textual evidence of Shakespeare's deep interest in snow and ice.

Another part of structuring your writing is to keep related information together. Suppose that you're discussing the health effects of pollution and you have three points about the ways that cars create dangerous fumes. At the very least consider whether to group the points together. (Sometimes. of course, you may have good reasons for keeping them separate.)

A book's index often reveals how methodical and organised the author really is, and how well he (or she) has grouped connected material together. If key topics in the index are revealed as page sweeps (such as 34–41), this is a better sign than if the same specific theme turns up in 10 or 20 different locations in the book.

Presenting the evidence and setting out the argument

In Critical Writing the emphasis is on producing reasons to support or (equally importantly) to discredit a position. Evidence is crucial for both kinds of activity, although clearly you need to produce more evidence for controversial claims than for common sense assertions that your readers may reasonably be expected not to need convincing of.

Writing comes in all shapes and sizes, but the essay format is often the way in which colleges demand it and so I concentrate on that style here. Academic essays are supposed to argue a certain position and provide reasons that support a conclusion. Thus they are ‘critical thinking’ in capsule form.

But, like life, an essay is more complicated than that. In Critical Writing you need to make a particular effort to identify conflicting positions and to acknowledge different views. A more sophisticated essay shows how the main conclusions follow from the evidence provided, but may also explore issues and arguments related to the question that don't support the eventual conclusions. In this important sense, a good essay consists of several arguments, some of which are in competition with each other.

And don't be dogmatic (I say dogmatically). Respect different views and approaches and display a spirit of negotiation in your Critical Writing.

Checking out the key principles of well-structured writing

Writing well requires three things — knowledge of your topic, organisation and communication skills. The last one is the Cinderella skill — not invited to the party — in many academic contexts. In this section, you can learn how to make all three elements come to you as naturally as breathing.

Lecturer Andrew Northedge is an expert in this area and here, to get you started, are some of his most useful points for his students.

Knowing what you're writing about

Andrew Northedge is a lecturer in the Open University in the UK. He specialises in writing guides for students, which include lots of ideas relevant to Critical Thinking.

The Open University is different from other universities in that its students are a mix of ages and backgrounds, often studying part time, and the courses have to be delivered, not in person, but at a distance, often via the Internet. Getting students to think critically is thus a particular concern of the Open University. Northedge urges students to spend a bit of time before they start writing to ask themselves just what they're meant to write. In other words, to try to identify the topics, information and ideas that a tutor — or more generally, future readers of the essay — will be looking for.

This may seem obvious, perhaps, but as Northedge says, writing is a particularly private activity — people retreat into a quiet corner on their own to do it. And if students spend a lot of time thinking about their own writing, and a bit of time thinking about the feedback later from tutors, most students never see what anyone else has written during their course. They live in a bubble and their writing is sealed off from public view. So make a special point of peering out!

Doing initial research

- Reading about your subject.

- Thinking about the issues.

- Making notes and perhaps doodling some ideas (check out Chapters 9 and 11 for more on this invaluable skill).

All this work improves your writing — and makes your arguments more effective — when you commit your ideas to paper.

Taking lessons from others

Of course, if you're a student doing an assignment, maybe don't look at essays on exactly your topic, or if you do so, make sure that it's after all the essays — your one and those you might be looking at — have been marked! (Otherwise, you're in danger of looking like you're copying ideas.) However, if your pieces of writing are regularly criticised for lacking clarity and structure — which is a vague sort of criticism and hard to act upon — comparing your efforts to those of someone whose writings have been praised for just these sorts of features can give insights.

Then, when you start writing, aim for simplicity and elegance over grandiose constructions intended to be huge and imposing. As Andrew Northedge sums it up:

There's no great mystery about what is good writing and what is not. Good writing is easy to read and makes sense. Poor writing is unclear and confusing; it keeps making you stop to try to work out what it's saying and where it's going.

—Andrew Northedge (The Good Study Guide, 2005)

Re-working that first draft

When you've written your first draft, you arrive at the often neglected after-writing stage. No, not turning the TV on, putting your feet up and getting the beer out! It's now the real work begins.

But just saying what the next paragraph is about isn't enough: you need to have a reason for your choice of content too — a sensible plan guiding the writing overall. The topics need to follow on from each other coherently and logically.

To make sure that this happens, you need either to be very good at writing ‘off the top of your head’ (what's sometimes called ‘steam of consciousness’ writing — the optimistic idea that your subconscious does all the work for you) or you need to have a pretty detailed and careful draft outline to guide your writing. You won't be surprised that for most people, a separate plan — one that delivers a sequence of points for the essay — together with links that connect them one to the next, works best in practice.

Such writing tricks are so easy that people often take them for granted. Yet they can make all the difference between readability — and indigestibility.

Deconstructing the question

The Critical Thinker's first job when writing is to think through exactly what that interest is — all the implications of the essay title or question. Don't tell the audience what you're interested in — tell readers only about what they want to know. The title or question is your indispensable guide to that.

In the academic context, the need to ‘answer the question’ is paramount. As Andrew Northedge, the Open University lecturer stresses, everything in an essay should relate to the question, and what's more, you need to make clear that this is the case. Northedge sees successful essays as featuring one long argument with every paragraph leading inexorably to, and supporting, the conclusion. Although that could be that there are no simple answers.

Producing effective conclusions

A crucial part of structuring an academic essay is ensuring that your conclusion is effective.

So, when you write the conclusion, don't worry about insulting the reader's intelligence — just go right ahead and spell things out. The same applies for all your earlier, subsidiary points too — your intermediate conclusions that build up to your final one (more on these in the later ‘Using intermediate conclusions’ section).

Choosing the Appropriate Style of Writing

Critical Writing requires keeping your audience in mind constantly. Therefore, you need to select the right information for them and present it in a way that's appropriate for them, avoiding unnecessary technicality or jargon.

Keeping your audience in mind

Noooo, not at all! You address not your supervisor but (at the very least) all the people the supervisor would expect your essay to need to convince too. For a student, rather obviously and literally, this would be examiners, but examiners too stand in for a wider audience. On a topic like this they'd judge an essay to be convincing and persuasive only if it would persuade any educated and reasonable person.

Considering the detail required

Any question set by an exam board or a tutor comes with certain expectations of the ‘level of detail’ wanted and about background knowledge within a certain subject domain — plus important assumptions about the style of writing. I know from personal experience that writing an interesting and highly creative narrative on a topic is pointless if the examiner wants a demonstration of knowledge of certain particular points. Dull, maybe, but that's how it is, and Critical Writers are nothing if not realistic.

To work out the relevant ‘domain of expertise’, to use a flowery phrase, ask yourself: what's the practical context? For example, if you're writing an essay on ‘What role can organic farming have in feeding the world?’, you need to identify the appropriate framework: is the context a course on economics, farming technology or social psychology? Or perhaps it's not a course at all, but an assignment for a company making, say, organic ice cream.

Student essays aren't exactly journal articles, let alone full-blown dissertations (thank goodness), but they're a highly structured kind of writing that must focus on developing an argument.

Getting Down to the Specifics of Critical Writing

At the start of this chapter I promised to cover the nuts and bolts of the Critical Writing skills and so now here they are. It all hinges on strategies for straightforwardness, keywords, evidence, signposts and conclusions.

Understanding that only gardens should be flowery

Rule 2 is avoid specialist terms and technical language where possible, and where you do need them clearly introduce and explain them. Similarly, flag up non-specialist terms that can be used in more than one way as ambiguous and define them for the purposes of the essay.

A good way to road check the comprehensibility of your writing, or at least of certain phrases, is to read it aloud. Remember, you don't have to appear to be a know-all. So simplify wherever possible.

Spotting and using keywords

Okay, so keywords are worth using. But which ones are they? Not all words are equal! Part of writing effectively is certainly to use a relatively small number of powerful words, in the sense that they help to shape your argument and guide readers through it.

No, the truth is a bit more subtle. A lot of the navigation of writing is implied: the first paragraph is probably going to introduce the topic, for example, and the last one is probably the conclusion.

- Keywords flagging up another argument in support of a view: Similarly, equally, again, another, in the same way, likewise.

- Keywords flagging up alternative perspectives and arguments: On the other hand (that's one of my favourites!), yet, however, but.

- Keywords rowing back against a criticism just advanced, in support of an earlier view: Nonetheless, even so, however, but (yes, keywords can serve different purposes).

- Keywords to tell the reader that you're about to draw some conclusions (get ready!): Therefore, thus, for this reason, because of this, it seems that.

Presenting the evidence and setting out the argument

Particularly in the academic context, where issues are complex and approaches can differ widely, a written essay is like a spoken debate, with several speakers who present their positions, and have to justify them too. Your role, as the author of the piece of Critical Writing, is to ‘chair the debate’ — asking searching questions, and (most exciting of all!) ruling on whether the speaker has met the objection or is starting to digress.

Critical Writers need to argue one thing one moment — then another contrary thing — and at any point change their tone and ‘their mind’. They have to think for several people all at once — it requires them to become almost schizophrenic! Plus, they continually try to judge the whole situation as reflected in what they've just written!

Thus, a danger always exists that a piece of Critical Writing can degenerate into a babble of different opinions, all competing for the reader's attention and appearing not to relate to each other. At worse, such writing becomes an unstructured mess.

Signposting to keep readers on course

Give directions! Use signpost words to guide your readers:

- To introduce a new idea: Write phrases such as ‘first of all’ or ‘some recent research shows’.

- To back up something already mentioned: Use words such as ‘similarly’ or ‘ indeed’.

- To indicate a change of direction and introduce alternative perspectives on an issue: Use phrases such as ‘on the other hand’ or words like ‘equally’ and ‘nonetheless’.

Paragraphs are another great tool to help readers navigate your writing. Ensure that each paragraph deals only with one idea, and in a similar spirit aim to give each idea its own paragraph.

- Deal with each idea in its own paragraph.

- Use the first line to signpost the contents of the paragraph.

- Arrange the paragraphs in a logical sequence.

Using intermediate conclusions

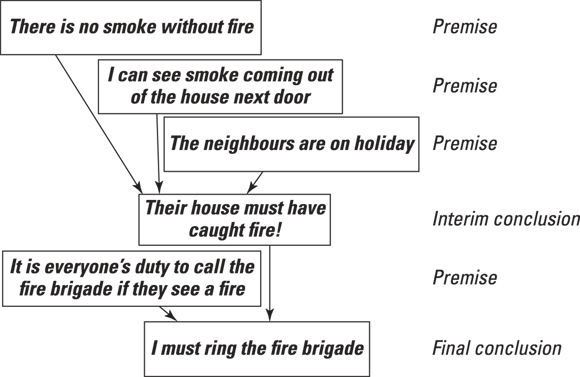

Fig 10-1: A simple argument with one intermediate conclusion.

So, intermediate conclusions are (surprise, surprise) a kind of conclusion — but they're also propositions (the series of claims in an essay about the world — about facts or logical relationships). In romantic novels, a proposition is usually a man asking for a woman's hand in marriage, but Critical Thinkers aren't interested in that kind of proposition!

Often a proposition is the length of a sentence, but propositions and sentences don't necessarily correspond. A sentence can easily contain several propositions. For example, the sentence ‘Eating sugar makes children fat and rots their teeth’ is really two propositions. (Consider, for example, that eating fried foods will make children fat but not rot their teeth.) On the other hand, some propositions may be spread over several sentences.

In an essay arguing for a particular point of view, the author will often simply assert at least one but, more usually, two or three) propositions which together make up — the premises or starting assumptions — and provide another proposition as the conclusion.

In fact, you can strip down a successful essay to just the propositions (P), intermediate conclusions (IC) and final conclusion (FC) (identified perhaps P1, P2, P3, IC1, IC2, FC), even if this means throwing out everything that made the essay colourful, readable and fun. As far as the logic goes, it wouldn't matter.

If humankind is to be survive an all out nuclear war on Earth, then people must be prepared to create colonies on the Moon. However, the Moon is a hostile environment. For a start, it contains very little water and there is no breathable atmosphere. It may be possible to import from Earth a certain amount of material to create a base but from then on the base must be self-sufficient and able to continually recycle everything humans need to survive.

Unfortunately, experiments with sealed communities in the desert on Earth have shown that there is always a degradation and loss of minerals and nutrients in such biospheres. Therefore the only way for a long-term Moon base to survive is for the astronauts to mine the surrounding rocks for minerals and water.

Recent measurements by orbiting satellites indicate that the Moon likely has adequate reserves of everything that a Moon Base may require, and so, the dream of ‘Man on the Moon’ is perhaps not so far-fetched after all.

Answers to Chapter 10’s Exercise

Here are my answers to the Intermediate Conclusions on the Moon exercise.

If the exercise was presented as a question it would be something like: ‘Is a Moon Base a realistic proposition?’ Then the structure of the argument seems to be as follows:

- Premise: People may need to create colonies on the Moon.

- Premise: The Moon contains very little water and has no breathable atmosphere.

- Intermediate conclusion: Therefore, the base must be self-sufficient and able continually to recycle everything humans need to survive.

- Premise: Experiments show that biospheres always feature a degradation of resources.

- Intermediate conclusion: Therefore the only way a Moon Base can survive is by mining the surrounding rocks for minerals and water.

- Premise: The Moon has adequate reserves of everything that a Moon Base may require.

- Final conclusion: A Moon Base is possible.

You confuse readers when you don't tell them your overall position early on and upfront. I know that keeping a few tricks up your sleeve is more exciting — or even better (like a detective story) subtly leading readers into believing something that's the opposite of what turns out, in a dramatic final paragraph, to be the case! — but it is confusing.

You confuse readers when you don't tell them your overall position early on and upfront. I know that keeping a few tricks up your sleeve is more exciting — or even better (like a detective story) subtly leading readers into believing something that's the opposite of what turns out, in a dramatic final paragraph, to be the case! — but it is confusing. View an index as a kind of X-ray of a book that reveals its hidden structure. Try indexing some of your own longer pieces of writing; you may be surprised to see how scattered your thoughts are! Even easier and quicker if you're word-processing is to search your document for certain words. Do you keep mentioning ‘paradigm’, for example, or have too many ‘buts’ and ‘howevers’? X-ray your own work by checking for key terms. Sometimes the check reveals problems!

View an index as a kind of X-ray of a book that reveals its hidden structure. Try indexing some of your own longer pieces of writing; you may be surprised to see how scattered your thoughts are! Even easier and quicker if you're word-processing is to search your document for certain words. Do you keep mentioning ‘paradigm’, for example, or have too many ‘buts’ and ‘howevers’? X-ray your own work by checking for key terms. Sometimes the check reveals problems! What about layout and graphics? After all, isn't a picture worth a thousand words? Well, maybe for writing holiday news, but not in Critical Writing. No, no, no! Don't use graphics to prove your arguments. Critical Writing isn't marketing. Use graphics only to illustrate ideas that you've presented first in the main text. Similarly, don't rely on headings or snazzy fonts and text styles to make your points. But you can use all these things to highlight ideas and signpost things to the reader. That's after all, what a For Dummies book is doing all the time. Look at the next heading — doesn't it help you quickly navigate the text?

What about layout and graphics? After all, isn't a picture worth a thousand words? Well, maybe for writing holiday news, but not in Critical Writing. No, no, no! Don't use graphics to prove your arguments. Critical Writing isn't marketing. Use graphics only to illustrate ideas that you've presented first in the main text. Similarly, don't rely on headings or snazzy fonts and text styles to make your points. But you can use all these things to highlight ideas and signpost things to the reader. That's after all, what a For Dummies book is doing all the time. Look at the next heading — doesn't it help you quickly navigate the text? Preparing before writing means:

Preparing before writing means: Keywords emphasise or indicate the focus or intentions of the writer. They ask the readers to think in a particular way, specifically to anticipate what's about to happen next. The use of appropriate keywords makes your writing much more effective.

Keywords emphasise or indicate the focus or intentions of the writer. They ask the readers to think in a particular way, specifically to anticipate what's about to happen next. The use of appropriate keywords makes your writing much more effective. This exercise (which I call Intermediate Conclusions on the Moon) makes this point clearer. Strip the following short passage down to its premises, intermediate conclusions and final conclusion (answers at the end of the chapter):

This exercise (which I call Intermediate Conclusions on the Moon) makes this point clearer. Strip the following short passage down to its premises, intermediate conclusions and final conclusion (answers at the end of the chapter):