CHAPTER 11

USE CASES IN GOVERNMENTS

Big data has myriad uses in governing on all levels, from the intergovernmental level in the United Nations to the local level in cities, small provinces, and townships all over the world. For the first time, governments can analyze data in real-time rather than rely on past and often outdated traditional reports to make decisions that affect today and tomorrow. Such information enables a government to make its services and processes more efficient, but it also closes the gap between immediate public needs and lagging government response. It is one of the best means to put government in sync with its constituents’ needs and concerns, in other words.

This chapter covers multiple use cases at several different government levels. However, use cases in the Department of Defense (DoD) and Intelligence Community (IC) are detailed in Chapter 10, as they require special mention and treatment that can distract from the focus here on general governance and citizen services. Folding those use cases into this chapter would also not do the DoD’s and IC’s herculean and often controversial data efforts justice.

Other government use cases such as those at the Department of Energy, Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and the United Nations Global Pulse are also touched upon in other chapters. This is because governments do not work in a vacuum. Public-private partnerships are common. Often government agencies share information in order to spur positive development throughout the entire community and thereby broaden the benefits to all constituents. In order to show this interplay as it applies to big data use, some government efforts are highlighted in several other chapters according to the industry each such effort aligns with. For example, you’ll find note of the Department of Energy’s big data efforts in Chapter 16 on energy and the CDC’s work noted in Chapter 13 on healthcare, and so on. However, the big data works of any given government agency are not necessarily contained in any one chapter, so you are likely to find mentions of them in several chapters, although none of the mentions are repetitive.

Indeed, two of the most notable trends that big data tends to accelerate are collaboration and a collapse or consolidation of industry divisions. In the commercial world, this phenomenon is clearly evident. One example is in the consolidation of the telecom and cable TV industries. Cable TV companies now routinely offer telecom services from home phones to mobile apps. Conversely, telecom companies offer TV services. Both are Internet Service Providers (ISPs). Because of this model convergence, industry outsiders and consumers tend to see the two very differently regulated industries as one.

EFFECTS OF BIG DATA TRENDS ON GOVERNMENTAL DATA

In the case of government work in big data, it is becoming increasingly difficult to point to a dividing line between what data belongs to the government and which belongs to a private concern because a primary third-party data source for enterprises and individuals is governmental data sets. Some of that data has always been public record and therefore available. However, before the advent of the Internet, this data was difficult to access due to the need to locally request it and the inability to easily find related data squirreled away in various government agency silos. Even after widespread access to the Internet, it was years before governments focused on providing data on the web to the public. It took years longer for the effort to become comprehensive. Now that data is widely available, plus data sets are continuously being provided by nearly every agency. Efforts such as the White House’s Project Open Data are also broadening the data resources available from the federal government.

On the other hand, the government needs and collects data from commercial sources and private individuals in order to develop comprehensive data sets before they can share them back again. One example of this is the government’s access to disease occurrences and health issues in individuals in order to generate reports on current and predicted disease epidemics or to discover a cause in an environmental health hazard.

Another example is social media. For instance, all posts on Twitter are now actively archived in the U.S. Library of Congress dating back to Twitter’s inception in 2006 and going forward presumably for at least the life of Twitter. At the time the archival efforts were announced, Twitter had already exceeded 200 million users. Most of them were U.S. citizens but certainly not all. Most users did not complain about the government collecting the information as it was a public forum by nature, except where users made their Twitter accounts private. Tweets that were deleted or locked are not collected by the Library. It is an immense data set that uniquely reflects the culture overall and the prevailing immediate thoughts of the day.

A 2013 Library of Congress whitepaper explains why the LOC was interested in adding the entirety of Twitter’s posts to its archives:

As society turns to social media as a primary method of communication and creative expression, social media is supplementing and in some cases supplanting letters, journals, serial publications and other sources routinely collected by research libraries.

Archiving and preserving outlets such as Twitter will enable future researchers access to a fuller picture of today’s cultural norms, dialogue, trends and events to inform scholarship, the legislative process, new works of authorship, education and other purposes.

According to a January 4, 2013 post by Erin Allen on the Library of Congress (LOC) blog, the most recent of LOC published updates, this is where the LOC’s efforts stand in regard to Twitter:

The Library’s first objectives were to acquire and preserve the 2006–2010 archive; to establish a secure, sustainable process for receiving and preserving a daily, ongoing stream of tweets through the present day; and to create a structure for organizing the entire archive by date.

This month, all those objectives will be completed. We now have an archive of approximately 170 billion tweets and growing. The volume of tweets the Library receives each day has grown from 140 million beginning in February 2011 to nearly half a billion tweets each day as of October 2012…

Although the Library has been building and stabilizing the archive and has not yet offered researchers access, we have nevertheless received approximately 400 inquiries from researchers all over the world. Some broad topics of interest expressed by researchers run from patterns in the rise of citizen journalism and elected officials’ communications to tracking vaccination rates and predicting stock market activity.

The size of the Twitter data set has undoubtedly grown since that report given the LOC reported it receives “nearly half a billion tweets each day as of October 2012.” However, according to the LOC whitepaper, the size of the data set at that time was as follows:

On February 28, 2012, the Library received the 2006–2010 archive through Gnip in three compressed files totaling 2.3 terabytes. When uncompressed the files total 20 terabytes. The files contained approximately 21 billion tweets, each with more than 50 accompanying metadata fields, such as place and description.

As of December 1, 2012, the Library has received more than 150 billion additional tweets and corresponding metadata, for a total including the 2006-2010 archive of approximately 170 billion tweets totaling 133.2 terabytes for two compressed copies.

Additional examples of the government collecting data on individuals include the census count mandated by Article I of the U.S. Constitution and unemployment reports by the Department of Labor, as well as many others. Other efforts are more controversial, such as those exposed by the Snowden revelations. Those are detailed in Chapter 9, which covers privacy and highlighted in Chapter 10, which includes use cases in the DoD and IC community.

In short, data is one big circle where all parties, be they individuals, non-profits, commercial interests, or government agencies, give and take data and collectively generate it. In many cases data ownership is a matter yet to be clearly defined because of this collective generation and distribution and the resulting confusion over who “created” what specific data or data elements. Additional data ownership issues are covered in earlier chapters. For the purposes of this chapter, we will look solely at use cases at all government levels without regard to data ownership issues, except to note where such concerns interfere with the effort.

UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL PULSE USE CASES

While the United Nations has always used data in the course of developing and executing its many missions, the development of Global Pulse, online at http://www.unglobalpulse.org/, signaled a new direction for the Executive Office of the United Nations Secretary-General. Global Pulse focuses exclusively on proactively harnessing big data specifically for economic development and humanitarian aid in poor and underdeveloped nations through policy advisement and action. Now, this is no easy task, as usually there are no sophisticated data brokers or commercial data collectors in many countries from which to buy or extract the data—big or otherwise. Therefore, collecting relevant data is largely a piecemeal affair.

Instead of doing big data in traditional ways, Global Pulse describes its data efforts as looking for “digital smoke signals of distress” and “digital exhaust” for telling clues, according to Robert Kirkpatrick, director of Global Pulse in the Executive Office of the Secretary-General United Nations in New York. An example of digital smoke signals are Twitter posts on job losses, spikes in food prices, natural disaster occurrences, disease outbreak, or other indicators of emerging or changing economic and humanitarian needs.

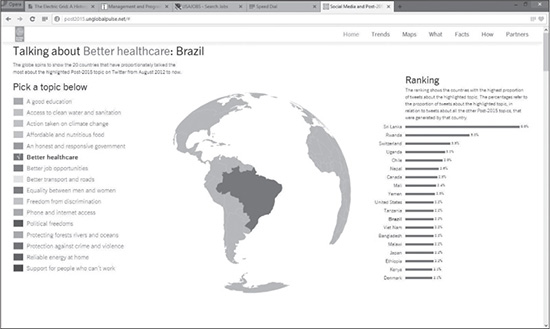

Figure 11.1 shows an online interactive visualization depicting which countries have the most people talking on Twitter about the list of development topics depicted. According to the 2013 Global Pulse Annual Report, through a partnership with DataSift, Global Pulse filtered 500 million Twitter posts every day looking for Tweets on these topics. This visualization depicts the end analysis. The interactive visualization can be found online at http://post2015.unglobalpulse.net/#.

Figure 11.1 An online interactive visualization depicting Twitter conversations on development topics of interest to Global Pulse.

Source: Global Pulse.

An example of digital exhaust is mobile phone metadata. Sometimes whiffs of digital exhaust can be caught wafting in public view but often Global Pulse has to resort to begging telecoms to share the information. The begging has resulted in meager offerings. “Telecoms don’t like to share the information for fear of user privacy concerns and feeding competitive intelligence,” said Kirkpatrick when he spoke as a member of a 2013 Strata NY panel for a media-only audience. “Sometimes they’ll give it to us if it’s been scrubbed, that is heavily anonymized, so competitors can’t see who their customers are.” The trouble with that of course is that the process of heavily anonymizing data can strip it of any useful information or limit inference from the aggregate. The second difficulty with that plan is that anonymized data can be reidentified by any number of entities motivated to do so. In essence, anonymization of the data does little to protect the information from prying eyes but it does sometimes impede Global Pulse and others in the development community in their humanitarian and economic development efforts.

Even so, Global Pulse continues on in its never-ending search of data from myriad sources that can help pin down emerging troubles anywhere in the world. In recognition that Global Pulse is not the only good willed entity in search of this information and dedicated to this cause, the unit shared its hard learned lessons with the global development community through several published guides. One example is its “Big Data for Development Primer,” which includes key terms, concepts, common obstacles, and real world case studies.

Another example is its guide titled “Mobile Phone Network Data for Development,” which contains research on mobile phone analysis. Global Pulse describes this guide’s usefulness this way:

For example, de-identified CDRs [call detail records] have allowed researchers to see aggregate geographic trends such as the flow of mass populations during and after natural disasters, how malaria can spread via human movement, or the passage of commuters through a city at peak times.

The document explains three types of indicators that can be extracted through analysis of CDRs (mobility, social interaction, and economic activity) [and] includes a synthesis of several research examples and a summary of privacy protection considerations.

Perhaps the most informative base concept found in Global Pulse’s “Big Data for Development Primer” is the redefining of the term big data for the development community’s purposes and the clarification in its use.

“Big Data for Development” is a concept that refers to the identification of sources of big data relevant to policy and planning of development programs. It differs from both traditional development data and what the private sector and mainstream media call big data… Big data analytics is not a panacea for age-old development challenges, and real-time information does not replace the quantitative statistical evidence governments traditionally use for decision-making. However, it does have the potential to inform whether further targeted investigation is necessary, or to prompt immediate response.

In other words, Global Pulse uses the immediacy of the information as an important element to support UN policy development and response. It does not, however, use big data as a replacement for traditional data analysis methods. This demonstrates a level of sophistication in big data use that is commonly missing in many private sector endeavors.

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT (NON-DOD OR IC) USE CASES

The U.S. government has made substantial strides in making more government data available to citizens, commercial and non-profit interests, and even to some foreign governments. That effort is continuing so you can expect to see more repositories and additional data sets made available over time.

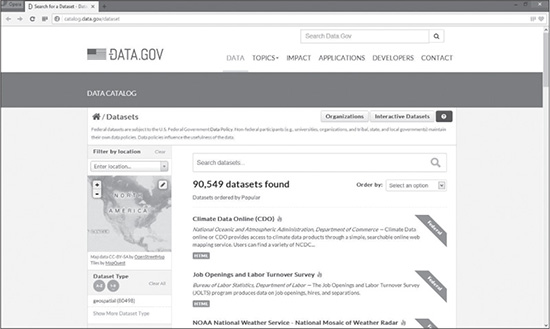

Data.gov is the central site for U.S. government data and is part of the Open Government Initiative. The Obama administration’s stated goal is to make the government more transparent and accountable. But the data provided also often proves to be an invaluable resource for researchers and commercial interests. The Data.gov Data Catalog contains 90,925 data sets as of this writing. You can expect that count to steadily climb higher over time and for the data sets to individually grow as well.

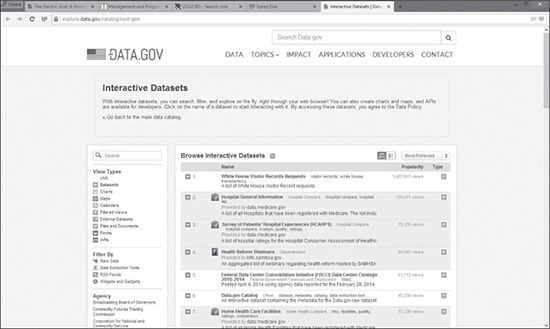

In order to illustrate the ease in accessing this information, Figure 11.2 shows sample Data.gov Data Catalog listings (although not the entire listing of course) and Figure 11.3 shows the alternate, which is interactive data sets. Both can easily be filtered according to your specific needs. The interactive data sets enable you to search, filter, discover, and make charts and maps right in your web browser. There are also APIs available for use by developers. Further, anyone can download the full list of Open Data Sites in either CSV or Excel formats.

Figure 11.2 Data.gov federal Data Catalog sampling.

Source: Data.gov.

Figure 11.3 Data.gov interactive data sets.

Source: Data.gov.

Beyond these data sets are international open data sets accessible through the Data.gov site. The full list of international open data sites can be downloaded from http://www.data.gov/open-gov/in CSV and Excel formats.

The second U.S. Open Government National Plan, announced in December 2013, added 23 new or expanded open government commitments to the previous data release plan announced in September 2011, containing 26 commitments total. The commitments address many areas pertinent to forming a more open government, but only a few pertain to data set releases.

In terms of usefulness to media, civic watchdogs, and researchers, the modernization of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and the transformation of the Security Classification System are notable in the second plan. In the case of the modernization of FOIA, the official federal plan calls for, among other things, a consolidated request portal so that requesters need not search for the right agency nor its protocols in order to make a request. It also calls for improved internal processes to speed the release of information once a request is made.

In regard to the second plan’s intended transformation of the Security Classification System, efforts are underway to prevent overclassification of government documents and thus drastically reduce the number and types of documents so protected from inception. Further, efforts are underway to declassify documents faster once the need for security classification has passed. These two efforts will lead to more government data coming available for public or commercial use.

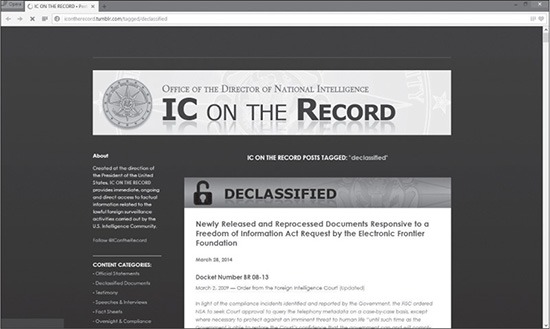

There is a third new source of data made available under the second plan. This one is sure to attract a lot of attention given the widespread American public and international concern after Snowden’s revelations on the NSA’s data-collection activities. As of this writing 2,000 pages of documents about certain sensitive intelligence collection programs conducted under the authority of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) were posted online at “IC on the Record” at this url: http://icontherecord.tumblr.com/tagged/declassified. Presumably more declassified documents are to come.

Figure 11.4 illustrates what declassified listings look like on that site and shows a sample document summary with updates and live links to the data.

Figure 11.4 The federal declassified documents page.

Source: Office of the Director of National Intelligence “IC on the Record” web page.

Specifically, “The Open Government Partnership: Second Open Government National Action Plan for the United States of America” issued by the White House, states:

As information is declassified, the U.S. Intelligence Community is posting online materials and other information relevant to FISA, the FISA Court, and oversight and compliance efforts. The Administration has further committed to:

Share Data on the Use of National Security Legal Authorities. The Administration will release annual public reports on the U.S. government’s use of certain national security authorities. These reports will include the total number of orders issued during the prior twelve-month period and the number of targets affected by them.

Review and Declassify Information Regarding Foreign Intelligence Surveillance. The Director of National Intelligence will continue to review and, where appropriate, declassify information related to foreign intelligence surveillance programs.

Consult with Stakeholders. The Administration will continue to engage with a broad group of stakeholders and seek input from the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board to ensure the Government appropriately protects privacy and civil liberties while simultaneously safeguarding national security.

All of these initiatives combined demonstrate that the federal government is using big data to inform its decisions but is also sharing data as a means of fueling or aiding private and commercial efforts as well as a public relations initiative.

STATE GOVERNMENT USE CASES

State governments vary greatly in their use of big data. Sophistication in the use of advanced analytics also varies from state to state. Some states rely on a mix of their own existing data and that which they pull from the federal government or is pushed to them. Other states are busy integrating data from cities, townships, counties, and federal agencies as well as integrating data across state agencies. Of the states most involved with multilevel data integration and advanced analytics, most are focusing on increasing efficiencies in internal processes, public services, and tax collections. A few have branched out into other big data uses, but most of those are at fledgling stages.

Most states are making at least public records data readily available online but you usually have to find that information in a state-by-state online search. Some state agencies also offer mobile apps that contain specialized data.

Figure 11.5 shows sample mobile applications displayed on the federal Data.gov site. These three are all Missouri state apps but plenty of other states offer apps, especially on tourism. At the moment, finding such apps requires a search of app stores by individual state and interest.

Figure 11.5 Missouri state mobile apps found on federal Data.gov website.

Source: Data.gov.

Most states have yet to build a central portal for data access as the federal government has done. Generally speaking, data is widely available at the state level but still requires the searcher to know which agency to go to or spend time and effort searching for it.

Figure 11.6 shows the Georgia Department of Public Health as an illustration of how some states are offering data at the state level but also pointing users to data available on the federal level that has not yet been incorporated in the state’s data set. Such measures are taken in an effort to make as much data as possible available, while the state works to digitalize their records and make them more easily accessible.

Some state data is also not made public because of privacy or regulatory concerns. The more geographically narrow the data set, the easier it becomes to reidentify individuals. Therefore, state and local governments must always be conscious of the potential threat to individual privacy and the potential failure in complying with regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

Figure 11.6 The state of Georgia’s health data and statistics.

Source: Georgia Department of Public Health.

As of this writing, no multistate data set groupings have been created by state governments that are voluntarily combining their data for the benefit of their region—at least none that I have found. Inevitably, regional data sets will come available. It is already common for states in a region to work together on several fronts from economic development to law enforcement. Combining their data regionally will only bolster those efforts.

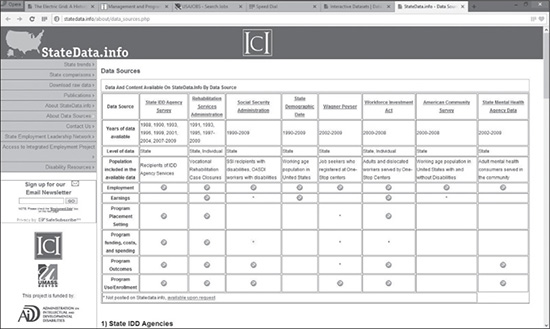

There are a few websites available that provide data on state-to-state comparisons, such as is found on StateData.info, a website supported by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), The Institute for Community Inclusion (ICI), the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, and University of Massachusetts, Boston. Such websites tend to share data focused within a special interest. In the case of StateData.info, and readily evident from the site’s list of supporters, the specific interest is state services made available to persons with disabilities. Other sites with other special interests exist as well.

See Figure 11.7, which shows a sampling of how StateData.info combines federal and state data to do its analysis. Most sites with special interests do the same or something similar. This is another reason why open federal data is so valuable to other entities besides government agencies. Note on the left upper side of Figure 11.7 that the site allows and enables downloading of its raw data, as well as quick views of the group’s analysis on state trends and state comparisons. This is yet another example of how data is so broadly shared that ownership of the data is almost impossible to determine. It is the openness of data, however, that enables the greatest advancements in both the public and private sectors.

Figure 11.7 Sampling of how StateData.info combines federal and state data to do its analysis.

Source: StateData.info.

State governments are using big data to varying degrees to guide their decisions, but also sharing data publicly and with private partners too. Much of the effort is focused on improving internal processes and on marketing public attractions and services. Few states are experimenting with much beyond these basics at this point. But this will change as state governments begin to understand big data tools better and acquire the talent needed to initiate new data projects.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT USE CASES

Very few local governments are working in big data now, due largely to funding cutbacks and a lack of talent capable of doing big data projects. For the most part, local governments are using traditional data collection and analysis methods largely confined to their own databases and local and state sources. An example of a local outside source is data from utility companies.

Large cities tend to be far ahead of the curve. See Figure 11.8, which shows New York City’s Open Data portal found at https://nycopendata.socrata.com. There the city provides over 1,100 data sets and several stories about how the city is using data. Figure 11.9 shows an NYC Open Data pullout detailing some of the efforts New York City is accomplishing through the use of all this data.

Figure 11.8 New York City’s Open Data portal.

Source: New York City website https://nycopendata.socrata.com.

Figure 11.9 NYC Open Data pullout detailing some of the efforts New York City is accomplishing through the use of big data.

Source: New York City website https://nycopendata.socrata.com.

However, interest in big data solutions at the local level is high in many towns, cities and counties, particularly those that are focused on cost savings, process efficiencies, and improving tax and fee collections. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) said that there is high interest in localized health data as well. Such requests are not surprising, for it is typical of budget-strapped local governments to turn to the federal and state governments for aid in obtaining localized data and analysis.

Local governments will eventually benefit from the growing spread of data from myriad sources and simpler analytics that can then be more easily used at the local level.

LAW ENFORCEMENT USE CASES

Of the few things that are truly certain in this life, growth in human population seems to top the list. Equally certain is the fact that government services and resources are typically stretched thinner with population increases. Law enforcement agencies on every level are repeatedly hit with budget cuts and manpower shortages and yet must find a way to perform to the public’s unwavering expectations.

For some time now, law enforcement agencies have incorporated a number of technologies to help them detect and fight crime. The array of tools currently at their fingertips is quite impressive. They include things like gun shot audio sensors, license plate readers, face recognition technology, GPS location tracking, in-car cameras, wireless graffiti cameras, and thermal imaging for area searches complete with corresponding police car monitors.

There are other tools more innovative than the standard fare of cameras and sensors too. One example is IDair’s system that can read fingerprints of people passing by up to 20 feet away from the device. As of this writing, IDair was already moving its product beyond military use and into the commercial realm. That means law enforcement and private companies can both buy it. Like security cameras on commercial property, police will likely be able to access data on commercially owned IDair systems too. The device is about the size of a flashlight and can be placed anywhere.

Another example is smart lighting systems for public places such as airports and shopping malls.

“Visitors to Terminal B at Newark Liberty International Airport may notice the bright, clean lighting that now blankets the cavernous interior, courtesy of 171 recently installed LED fixtures,” writes Diane Cardwell in her article in The New York Times. “But they probably will not realize that the light fixtures are the backbone of a system that is watching them.”

“Using an array of sensors and eight video cameras around the terminal, the light fixtures are part of a new wireless network that collects and feeds data into software that can spot long lines, recognize license plates and even identify suspicious activity, sending alerts to the appropriate staff.”

Other examples in innovative law enforcement technologies include diagramming systems, crime mapping, evidence collection systems, police pursuit reduction technologies, and cameras for police dogs.

Paul D. Schultz, Chief of Police in Lafayette, Colorado described those technologies in his post in The Police Chief magazine this way:

Evidence and deterrence: Crime scene investigations are also aided by these systems in scanning for physical evidence. Imagers can detect disturbed surfaces for graves or other areas that have been dug up in an attempt to conceal bodies, evidence, and objects. The device can also scan roadways for tire tracks or other marks that are not visible to the naked eye.

Proactive imager surveillance enables officers to scan public parks, public streets, alleys and parking lots, public buildings, transportation corridors, and other areas where individuals do not have an expectation of privacy.

Diagramming systems: Thanks to improvements in computer technology, crime scenes and collisions can now be diagrammed in a matter of minutes, as compared with hours just a few years ago. The systems that make this possible are highly accurate and easy to use, and they create extremely professional-looking images for use in court or for further analysis.

The high end of diagramming technology is the state-of-the-art forensic three-dimensional scanner that uses a high-speed laser and a built-in digital camera to photograph and measure rapidly a scene in the exact state in which the first responder secured it.

Crime mapping: The ability to depict graphically where crime has occurred and to some extent predict future crime locations enables field commanders to direct patrols through intelligence-led policing. The days when officers patrolled random areas hoping to catch the bad guys are giving way to a new era in which agencies use crime maps of every patrol district to assign officers to patrols in a reasonable and logical manner.

Reducing police pursuits: New systems that integrate the ability to track a suspect vehicle through a Global Positioning System (GPS) device that attaches to the suspect vehicle are reducing the need for police pursuits. This technology enables officers to apprehend a dangerous suspect at a later date when the safety of the community can be maximized.

Cameras for K-9 units: In the near future, agencies will be able to equip their K-9 units with cameras and two-way radio systems that will allow a K-9 handler to stay a safe distance from a dangerous event while at the same time providing command and control of a police dog. This technology will be useful for search-and-rescue operations as well as dangerous-building searches. Testing of a prototype system is supposed to begin this year [2014].

While all these tools help law enforcement and security forces cover more ground and collect more evidence, they also generate a continuous stream of data. For that data to be helpful, agencies and security personnel must be able to parse and analyze it quickly. Big data tools are essential in making the data useful.

However, it is not only machine data that is useful to law enforcement, but social media and other unstructured data as well. Again, big data tools are useful in collecting, parsing, and analyzing this data, too.

While the majority of big data use cases in law enforcement pertain to actively fighting crime, collecting evidence and preventing crime in the agency’s jurisdiction, big data tools and techniques are increasingly also used to share and integrate crime data between local districts and between agencies at all government levels. Further, big data is now being actively considered as an aid for internal needs such as for operational compliance and process improvements.

SUMMARY

In this chapter you learned how governments from the federal to the local level are using big data. You learned that a handful of big cities are well ahead of the curve in both using and sharing big data. Smaller cities, townships, and county governments tend to be woefully behind largely due to budget and talent constraints. The majority of those strive to at least make data from public records available, but many are hoping that the federal and state governments will eventually provide them with more granular data useable on the local level.

State governments vary widely in both commitment to using big data and in proficiency. However, the goal is almost universal: to make data, big data tools, APIs, and mobile apps widely available to the public. In the interim, some states and state agencies are providing what data they have now, while also pointing users to federal data in an attempt to make as much data as possible.

As of this writing, no multistate data set groupings have been created by state governments that are voluntarily combining their data for the benefit of their region. However, there are a few websites available that provide data on state-to-state comparisons, such as is found on StateData.info. Those tend to address special interest issues rather than broader comparisons.

You also learned that the U.S. government has made substantial strides in making more government data available to citizens, commercial entities, and non-profit interests, and even to some foreign governments. That effort is continuing so you can expect to see more repositories and additional data sets made available over time. Data.gov is the central site for U.S. government data and is part of the Open Government Initiative.

You also learned that international and foreign data sets are also available on Data.gov/open-gov. Indeed, international sharing of data is commonplace to a degree. Even the United Nations is interested in obtaining and using big data from a variety of countries.

While the United Nations has always used data in the course of developing and executing its many missions, the development of Global Pulse, online at http://www.unglobalpulse.org/, signaled a new direction for the Executive Office of the United Nations Secretary-General. Global Pulse focuses exclusively on proactively harnessing big data specifically for economic development and humanitarian aid in poor and underdeveloped nations through policy advisement and action. Now, this is no easy task, as usually there are no sophisticated data brokers or commercial data collectors in many countries from which to buy or extract the data.

Instead of doing big data in traditional ways, Global Pulse describes its data efforts as looking for “digital smoke signals of distress” and “digital exhaust” for telling clues. An example of digital smoke signals are Twitter posts on job losses, spikes in food prices, natural disaster occurrences, disease outbreak, or other indicators of emerging or changing economic and humanitarian needs.

In short, governments at every level are seeking to use and share big data to better serve their constituents, spur innovative economic development, and to provide humanitarian aid.