CHAPTER 18

USE CASES IN BANKING AND FINANCIAL SERVICES

Banking and other financial services institutions are a study in contradictions. On the one hand they traditionally excel at calculating and containing risks, which means of course that they generally excel at using data effectively. On the other hand, they’re not doing so well in using big data.

DEFINING THE PROBLEM

Big data tools are not so much the main problem for this group, although some are certainly struggling with those, rather they generally suffer from a “brain rut,” where their thinking on the various aspects of their business models, product lines, risk calculations, and investments is so deeply rooted in tradition that they often have difficulty branching out into more creative approaches. When they do try to break free of their rut, they sometimes do so by throwing caution to the wind as we saw happen in the financial crisis leading to the last worldwide recession. Somehow far too many investment banks thought disregarding prudence and risk control was necessary in spurring innovation and creating new profits. That of course was not the case and the rest as they say is history.

When things went sour for financial institutions during and after the recession, most retreated to the old ways and clutched their on-hand cash with a tighter grip. Credit availability dipped to almost zero for a good while as a result. Now credit is more available from traditional institutions but nowhere near where lending was before 2008–09. The tendency is to still go overboard in risk reduction, a situation further channeled by increased federal laws and regulations enacted in recent years. The end result is to extend credit only to a small percentage of customers and prospects who are largely most notable for somehow escaping punishing blows from the recession. In other words, lending prospects who suffered losses in the recession but are otherwise responsible borrowers are almost entirely ignored by traditional lenders.

The problem with this approach in traditional lending is three-fold. For one thing, shrinking one’s customer base is always a bad idea. Fewer customers generally equates to fewer sales, smaller profits, and a higher future loss in customer attrition. For another, this approach opens the door wide for competitors to encroach and even seize the bank’s market share. Hunkering down in a defensive position encourages aggressive competitors to go on offense and move in on your territory. And third, while traditional financial institutions spurn potential customers and new alternative lenders welcome them with open arms, the public perception of banks shifts from essential financial service providers to nonessential, perhaps irrelevant, players in a crowded field.

In short, business-as-usual in financial services is crippling the industry.

Some financial institutions recognize this and are trying to change things by using big data more proactively and creatively but with mixed results. Gartner analyst Ethan Wang explained in his October 22, 2013 report what Gartner found is happening on this front:

In Gartner’s recent survey, most organizations were at the early stages of big data adoption—and only 13% of surveyed banks had reached the stage of deployment. Many banks are investigating big data opportunities and initiating big data projects on a “me too” basis. Their executives have heard—though not seen—that their competitors are exploiting big data, and they are afraid of being left behind. They find, however, that it is difficult to monetize big data projects based on an explicit business ROI.

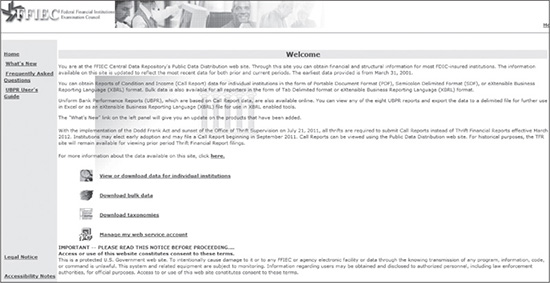

To learn how to monetize data and calculate ROI, see Chapter 7. In this section, the focus will be on use cases and strategies for banks and financial services. To learn more about the current financial and structural information for most FDIC-insured institutions, you can download data on individual institutions or bulk data on the entire group from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Central Data Repository’s Public Data Distribution website at https://cdr.ffiec.gov/public/. Figure 18.1 shows information on that repository.

Figure 18.1 The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Central Data Repository and data sets.

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Central Data Repository’s Public Data Distribution website at https://cdr.ffiec.gov/public/.

USE CASES IN BANKS AND LENDING INSTITUTIONS

Like organizations in many industries, banks have plenty of data on hand and more at their disposal. So the problem is not the lack of total information, but in figuring out how to use it and for what purposes.

Surprisingly, some banks are using big data successfully but fail to recognize that is what they are doing. By not recognizing these efforts for what they are, the banks fail to grasp and leverage lessons learned in big data projects. Gartner analyst Ethan Wang explains this phenomenon in the same report cited previously:

It is worth noting that many banks are seeking or implementing what could be regarded as big data initiatives—frequently at the business-unit level—but are not referring to them as big data projects. Instead, they are often identifying them by the business problems or needs they are trying to address, such as real-time fraud detection and prevention, systemic risk analysis, intraday liquidity analysis or the offering of information-based value-added services. It is not unusual for both business-unit leaders and bank CIOs to fail to recognize the big data nature of these activities. Bank CIOs and business-unit leaders should review these current projects, where business cases and key performance indicators have already been established, and identify when these create opportunities to show the value and role of big data. This would save the efforts involved in building a business case and calculating a financial forecast from scratch.

Many banks are unsure where to start with big data. First, look to see if you already have projects in motion that are using copious amounts of data. If so, find and use the lessons learned within them as Wang suggests. Otherwise the best place to start is in any activity where you currently use data analysis. Choose one or a few of those that you judge to be in most need of improvement and then begin a pilot project or two accordingly.

“Almost every single major decision to drive revenue, to control costs, or to mitigate risks can be infused with data and analytics,” said Toos Daruvala, a director in McKinsey’s New York office, in a McKinsey & Company video interview online titled “How Advanced Analytics Are Redefining Banking.”

Daruvala also gave examples in that video interview on how three banks specifically used big data to their advantage:

Let me give you a couple of examples of real-world situations where I’ve seen this applied quite powerfully. There was one large bank in the United States, which had not refreshed their small-business underwriting models in several years. Certainly not post the crisis. And they were getting worried about the [risk] discriminatory power of these models.

The Gini coefficient of their models—which is just a measure of how powerful a model is in terms of its ability to discriminate between good risks and bad risks—was down in the sort of 40- to 45% range. What these folks did was developed a 360-degree view of the customer across the entire relationship that that small business had with the bank, across all the silos. Not easy to do; easy to talk about, not easy to do.

And then what they did was selectively append third-party data from external sources, trying to figure out which of those third-party pieces of information would have the most discriminatory power. And they applied the analytical techniques to redo their models and essentially took the Gini coefficient of the models up into the 75% range from the 40- to 45% range, which is a huge improvement in the discriminatory power of those models.

Another bank that we were working with was in the developing markets, where data to begin with is pretty thin on consumers. And they decided that they would try to actually get data from the local telco. The paying behavior for the telco is actually a great predictive indicator for the credit behavior with the bank. And so they bought the data, appended that to the bank data, and again had a huge improvement in underwriting.

Another institution, a marketing example, where we ended up using, again, that 360-degree view of the consumer and then appending some external data around social media to figure out what’s the right next product to buy for that consumer and then equip the front line to make that offer to that consumer when they walk into the branch or when they call into the call center. And the efficacy of their predictor models on next-product-to-buy improved dramatically as well.

So these are examples of things that you can do. And part of the reason why this is so important is that in the banking world, of course, in the current regulatory and macroeconomic environment, growth is really, really, really hard to come by.

While those are good examples, they are only a few ways big data can best be used by banks and financial institutions. Other use cases include strategic planning, new revenue stream discovery, product innovation, trading, compliance, and risk and security. For more information on how financial services can use big data in risk and security efforts, see Chapter 12, “Use Cases in Security.”

Meanwhile, traditional financial institutions had better speed their use of big data in finding new business models and products because disruptive competitors are already on the scene.

HOW BIG DATA FUELS NEW COMPETITORS IN THE MONEY-LENDING SPACE

While banks and other traditional lending institutions struggle with how, when, where, and why to use big data, disruptive competitors are using big data to bore into their market strongholds. Where once people were at the mercy of traditional lenders and the only alternatives were pawn shops and predatory secondary lenders, there now exist alternative financiers that pose considerable threats to banks while opening substantial opportunities to borrowers. One example that immediately comes to mind is online banks that can compete more aggressively because they have less overhead since they do not carry physical bank branches and the associated operational costs on their balance sheets. But these are still banks that largely function like all traditional banks.

Examples of truly new alternative credit sources include PayPal Working Capital, Amazon Capital Services, CardConnect, and Prosper, as well as co-branded credit cards such as those offered by major retailers like Target, Macy’s, and Sears in partnership with companies such as Visa, MasterCard, and American Express.

THE NEW BREED OF ALTERNATIVE LENDERS

Some of these new lenders, such as PayPal Working Capital and Amazon Capital Services, lean heavily on their own internal data to measure a loan applicant’s credit worthiness. In other words, they are loaning money only to their own customers based on those customers’ sales performance within the confines of the lender’s business. But there are other new lenders on the scene that use a peer-to-peer model to issue personal and business loans for just about anything.

PayPal Working Capital

For example, PayPal doesn’t require a credit check to qualify for the loan. Instead, credit worthiness is established by the borrower’s record in PayPal sales. A PayPal spokesperson explained the process in an interview with me for my article on the subject in Small Business Computing (see http://www.smallbusinesscomputing.com/tipsforsmallbusiness/how-big-data-is-changing-small-business-loan-options.html):

“WebBank is the lender for PayPal Working Capital, and since WebBank is responsible for verifying the identity of the applicant, it must use a trusted third-party for this verification,” says PayPal’s spokesperson. “PayPal chose Lexis Nexis as the partner for this verification, and many large banks use Lexis Nexis. Buyers are qualified based on their PayPal sales history.”

There’s also no set monthly payment, since PayPal allows a business to repay the loan with a share of its PayPal sales. When there are no sales, there is no payment due.

“It’s a revolutionary concept that allows PayPal merchants the flexibility to pay when they get paid,” says PayPal’s representative. PayPal Working Capital does not charge periodic interest. Instead it offers one affordable fixed fee that a business chooses before signing up—there are no periodic interest fees, no late fees, no pre-payment fees, or any other hidden fees.

PayPal’s rep pointed out how this practice compares to traditional credit, where “businesses report they seldom know how much they ultimately pay in interest and other fees.”

PayPal’s model already competed with banks in payment and money transfers. Now with PayPal Working Capital it also competes with traditional financial institutions in small business lending. In addition to the additional revenue stream, PayPal also benefits by strengthening its brand and its stature as a solid financial services resource in the minds of small business owners.

Prosper and Lending Club

By comparison, Prosper and Lending Club operate a peer-to-peer lending model. Lending Club has been around since 2007 and as of March 31, 2014, it had issued over $4 billion in personal loans over its platform. Lending Club is even selling its paper to banks now. For example, on May 5, 2014, Lending Club announced “Union Bank will purchase personal loans through the Lending Club platform, and the two companies will work together to create new credit products to be made available to both companies’ customer base.”

Prosper Funding LLC, according to the company’s website, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Prosper Marketplace, Inc. The founders are former managing partners of Merlin Securities: Steven Vermut and Aaron Vermut. Sequoia Capital and BlackRock are among the investors backing Prosper Marketplace, Inc.

Prosper’s loan originations grew by 413% in one year to exceed $1 billion in personal loans. As of this writing, Prosper said its community contained 75,699 investors and 93,321 borrowers and that the majority of the $1 billion borrowed to date was used for debt consolidation. This means traditional lenders lost revenue from interest payments in this deal as borrowers paid off debt early. Further, Prosper said much of the remaining money borrowed was for car loans and home renovations, which siphons business away from banks and traditional lending organizations.

In an April 3, 2014 press release announcing Prosper surpassed the $1 billion personal loan mark, the company said:

A driving factor in the company’s growth has been the ease with which people can obtain a loan through Prosper compared to traditional methods of lending. Over 50% of the loans on the Prosper platform are funded within two days of the borrower starting the application process, and rates and loan options can be checked within a matter of seconds with no impact to a person’s credit score. Loans are competitively priced, and based on a person’s personal credit, rather than a generic rate across the board. They are also fixed-rate, fixed-term loans with no prepayment penalties. In addition, borrowers have the convenience of applying anytime day or night online, and receive their FICO score for free as part of the application process.

How did the alternative financiers such as PayPal Working Capital, Amazon Capital Services, Lending Club, and Prosper come to be? First and foremost these models came from the ability to replace or augment conventional historical analysis with near- and real-time data analysis and to predict future risk via new predictive analytics. With these newfound big data capabilities, new competitors in the space were able to make loans to persons and businesses that traditional lenders turned away and to do so with minimal risk. Further, these new competitors were also able to fashion entirely new lending models that banks could not easily compete with.

RETAILERS TAKE ON BANKS; CREDIT CARD BRANDS CIRCUMVENT BANKS

Co-branded retail credit cards are also putting some pressure on the future of banks. These cards are easier for consumers to qualify for than bank-issued credit cards, although they are usually offered at higher interest rates. They should not be confused with store credit cards, which can only be used for credit in a specific store. Co-branded credit cards can be used anywhere just like a traditional bank-issued credit card. In other words, they work exactly like a bank-issued Visa, MasterCard, or American Express. Indeed, from a consumer’s perspective they are, for all practical purposes, identical except instead of having a bank logo on the card, there is a store logo. Both of these credit card types also carry the payment card brand, such as Visa or MasterCard.

It should be alarming to banks that leading payment card brands such as Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are teaming with so many non-banks for the purpose of issuing credit. Further, these cards are generating a considerable amount of data for competing entities that was formerly contained and controlled by banks and traditional lending institutions. Plus, consumer use of these cards generates additional data from the stores on specific user shopping habits and other behaviors that can be further leveraged in many ways, not the least of which is to hone retailers’ competitiveness and leverage against banks. Many retailers resent banks for charging what they perceive as high merchant and processing fees. They are eager to find ways to reduce or eradicate these costs, and indeed many options have arisen to fill the need.

Consider Walmart’s continued encroachment into financial services as an example. The giant retailer and the nation’s largest private employer already offers low-cost money transfers, pre-paid debit cards, check cashing services, and auto insurance. Are financial institutions worried about Walmart and other retailers competing on financial services? Yes, they are.

In an April 30, 2014 report in Yahoo! Finance titled “The Bank of Walmart: Can the retail giant unseat the big financial institutions?”, Kevin Chupka wrote:

Walmart tried to become a bonafide bank back in 2007 but pulled their application after what The New York Times said was “a firestorm of criticism from lawmakers, banking industry officials and watchdog groups.” Banks bristled at the potential competition and lawmakers were in the midst of crafting a bill to block non-financial companies from creating a bank in order to protect neighborhood banks and big bank profits.

Still, their failure to become a real bank hasn’t stopped Walmart from being the go-to place for low-income consumers who don’t have a bank account. Check cashing fees and debit card refills are much cheaper at Walmart and they have taken a significant share of that business away from traditional financial service companies.

As more consumers learn it’s easier to qualify for credit cards from airlines, retailers, and other non-bank companies—and where the loyalty rewards are typically better too—fewer consumers will turn to banks for these services. As they learn other financial services are more freely offered and at lower fees by non-bank entities, consumers will drift further still from banks, which is not necessarily a “bad” thing in the aggregate. Nevertheless, when combined these trends erode market share for banks and other traditional financial institutions.

THE CREDIT BUREAU DATA PROBLEM

As mentioned earlier, banks and other traditional lending institutions over-tightened credit in response to the financial crisis and recession and have since loosened their grip some, but for some, not enough to maintain profitability over a longer timeframe. It is the classic pendulum over-reaction to past errors in their work. Granted, the repercussions were profound and thus a rapid reinfusion of prudence was certainly in order to stabilize individual institutions and the industry as a whole. However, lending decisions are still largely fear-driven to this day. By reacting out of fear rather than from knowledge gained through data, the banks lose billions in potential business.

On top of that, traditional lending institutions place too much faith in outside traditional risk-assessment sources, namely traditional credit bureaus. Therefore the lenders are further stymied by the problems in traditional credit bureau data such as too little data, irrelevant data, outdated credit rating systems, and virtually no distinction between potential borrowers who are truly a credit risk and those who were set back temporarily by the recession but otherwise pose little risk.

Further, there have been documented cases where traditional credit bureaus presented dirty data—corrupted or incorrect data—to lenders as though it were clean and factual. In many cases, once aware of errors in consumer data, credit bureaus are exceptionally slow in correcting it or otherwise make data correction a difficult process. Incorrect credit bureau data diminishes a traditional lender’s ability to correctly assess risk in any given loan applicant. To add insult to injury, lending institutions pay credit bureaus for specific data that may have little to no actual value.

On July 26, 2013, Laura Gunderson wrote a report in The Oregonian on just such a dirty data case involving Equifax, one of the three major credit bureaus in the United States:

“A jury Friday awarded an Oregon woman $18.6 million after she spent two years unsuccessfully trying to get Equifax Information Services to fix major mistakes on her credit report,” reported Gunderson. “Julie Miller of Marion County, who was awarded $18.4 million in punitive and $180,000 in compensatory damages, contacted Equifax eight times between 2009 and 2011 in an effort to correct inaccuracies, including erroneous accounts and collection attempts, as well as a wrong Social Security number and birthday. Yet over and over, the lawsuit alleged, the Atlanta-based company failed to correct its mistakes.”

Unfortunately, this case is not an isolated incident. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reported in February 2013 that its study uncovered a significant number of credit reporting errors. “Overall, the congressionally mandated study on credit report accuracy found that one in five consumers had an error on at least one of their three credit reports. One in 20 of the study participants had an error on his or her credit report that lowered the credit score.”

Jill Riepenhoff and Mike Wagner wrote a May 6, 2012 report in The Columbus Dispatch on the Ohio paper’s own investigation into the accuracy of credit bureau data:

During a yearlong investigation, The Dispatch collected and analyzed nearly 30,000 consumer complaints filed with the Federal Trade Commission and attorneys general in 24 states that alleged violations of the Fair Credit Reporting Act by the three largest credit-reporting agencies in the United States—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion.

The complaints document the inability of consumers to correct errors that range from minor to financially devastating. Consumers said the agencies can’t even correct the most obvious mistakes: That’s not my birth date. That’s not my name. I’m not dead.

Nearly a quarter of the complaints to the FTC and more than half of the complaints to the attorneys general involved mistakes in consumers’ financial accounts for credit cards, mortgages or car loans. Houses sold in bank-approved “short sales,” at less than the value of the mortgage, were listed as foreclosures. Car loans that had been paid off were reported as repossessions. Credit cards that had been paid off and closed years earlier showed as delinquent.

More than 5% complained to the FTC and more than 40% to the attorneys general that their reports had basic personal information listed incorrectly: names, Social Security numbers, addresses and birth dates. An Ohio man said his report identified him as having been a police officer since 1923. He was born in 1968. A woman in her 60s said that her credit report listed her as 12 years old.

More than 5% complained to the FTC that their reports contained an account that did not belong to them. Many of those accounts involved debts that had been turned over to collection agencies. A woman in Georgia complained about a medical-collection account on her report. It was for treating prostate cancer.

Nearly 200 people told the FTC that their credit reports listed them as deceased, cutting off their ability to access credit.

More than half of all who filed complaints with the FTC said that despite their best efforts, they could not persuade the three major credit-reporting agencies to fix the problems.

Gunderson confirmed in her report in The Oregonian that the Oregon Attorney General office was seeing much the same thing across all three major credit bureaus: “Since 2008, Oregon consumers have filed hundreds of complaints about credit bureaus with the state’s Attorney General. Those complaints include 108 against Equifax, 113 against Experian, and 70 against TransUnion.”

While most traditional lending institutions add factors to their decision formulas other than credit ratings from the big three credit bureaus, they are still heavily dependent on that data and overweigh its worth in the final lending consideration.

For banks and other traditional financial institutions to better assess their risk and realistically expand revenue from loans and other credit and financial services, they have to import significant data from sources other than credit bureaus and develop better risk assessment algorithms. Further, they have to develop the means to assess the credibility, accuracy, and validity of data sources and the data they supply. In other words, they have to monitor the data supply chain closely and audit sources routinely and extensively. The days of meekly accepting credit bureau data, or any data, at face value are long gone. The business risk in that behavior is unacceptably high.

All internal data silos need to be immediately opened and the data reconciled so that all internal data is available for analysis. In this way, traditional financial institutions can better assess risk in existing customers and develop new ways to retain customers, despite the allure of offers from competitors both new and old. Financial institutions can also use data on existing customers to help identify characteristics they need to look for in prospects in order to add profitability and sustainability for their business.

A WORD ABOUT INSURANCE COMPANIES

As noted, Walmart began offering auto insurance to consumers through a partnership with AutoInsurance.com in April 2014. A New York Times report by Elizabeth Harris said the giant retailer explains that effort this way:

Daniel Eckert, senior vice president of services for Walmart U.S., said the company is using its size to broaden its offerings for customers and to get an edge on the competition. While some companies have rebounded more easily from the recession, Walmart’s core customer base, largely low-income people, has struggled to regain a foothold, so its sales have been sluggish. Mr. Eckert said this was just another way to help customers save money and simplify a complicated process… “What it does,” he said, “is it engenders trust.”

The issue of trust is huge in establishing and retaining customer loyalty and in brand building. While Walmart excels at both, despite collecting huge amounts of customer data, auto insurance companies are not quite hitting that mark. As discussed in Chapter 15, “Use Cases in Transportation,” data collection devices provided to consumers by auto insurers to track driving habits and price premiums accordingly, are viewed with suspicion by consumers and watch groups alike. That’s because a conflict of interest is inherent in the exercise. Detractors can easily discern that there is little motivation for insurance companies to reduce their premiums and thereby reduce the company’s revenues. There is, however, significant opportunity and motivation to increase premium costs on most drivers for the slightest perceived driving infraction.

In contrast, Walmart, despite watch groups’ concerns over many of its actions, has been able to position itself as a champion of its customers in part by offering services seemingly unrelated to its core business. Such offerings are generally perceived by customers as an effort to help them afford more than they would otherwise rather than an attempt to sell them more products and services.

Yet Walmart is very good at using big data to precisely target and increase sales at the micro and macro levels. Bill Simon, president & CEO of Walmart U.S., said as much at a Goldman Sachs Global Retailing Conference held on September 11, 2013. The entire transcript, redacted in parts, provided by Thomson Reuters StreetEvents is available online in PDF form. Here is part of what Simon said about Walmart’s use of big data at that event (found on page nine of the transcript):

…while we don’t have a traditional loyalty program, we operate a pretty big membership club that is the ultimate in loyalty programs. So we have that set of data that is available to us. If you take that data and you correlate it with traceable tender that exists in Walmart Stores and then the identified data that comes through Walmart.com and then the trend data that comes through the rest of the business and working with our suppliers, our ability to pull data together is unmatched.

We’ve recently stood up a couple years ago a group that’s designed specifically to understand that and find ways to leverage that in the Company. And so, while data is a commodity today or an asset today, the opportunity for us to use it I think is as good as if not better than others because of the wealth and the breadth. Loyalty cards only give you kind of one dimension data and we get to see it from multiple different sources. We are using it in all kinds of ways today. So magically we know exactly which SKUs are bought in that particular geography because of our ability to understand the data. We think that gives us a competitive advantage that others would really struggle to get to.

Interestingly, The New York Times reported in the article cited above that “A Walmart spokeswoman said the company would not have access to customer data collected on AutoInsurance.com” through its new auto insurance offering. Harris, the author of that report, describes the relationship between Walmart and AutoInsurance.com this way:

The website, AutoInsurance.com, allows consumers to review prices at several insurance companies and contrast them with their current insurance. Effectively, Walmart and AutoInsurance.com will be marketing partners. Walmart will promote the website in its stores, and receive a monthly fee in return, while AutoInsurance.com will collect commissions when insurance is sold on its site. Customers will also be able to access the site from Walmart.com.

And so there appears to be the answer as to why Walmart, one of the best of all big data practitioners today, “would not have access to customer data collected on AutoInsurance.com” after the CEO said “…trend data that comes through the rest of the business and working with our suppliers, our ability to pull data together is unmatched.” The answer is likely that Walmart will pull the data it needs from customers who access the site from Walmart.com. Truth be told, it’s doubtful that the retailer needs very much of the data entered on and gathered by the AutoInsurance.com site anyway. After all, driving records are easily accessed elsewhere as are accident reports and vehicle repair records should Walmart ever decide it needs that information. For whatever reason, Walmart is not accessing the AutoInsurance.com data, and the statement that it won’t is a great public relations move. It casts the company as respectful of privacy and self-restrained in its big data actions, whether or not that is actually the case.

Do not mistake the intent here, which is not to disparage or endorse Walmart in any way. I point to its excellent skills, some of which are beyond its big data collection and analysis, as a credible and serious threat to any industry it cares to take on. That is to say that should the company decide to try to move into insurance, be that health, life or auto, as it has tried with mixed success to move into banking, the insurance industry will have a serious new competitor with which to contend.

Further, helping customers save money on financial essentials also helps them increase their disposable income, which in turn might lead to an increase in sales for Walmart. The retailer is smart in cultivating and conserving its customer base much like a paper manufacturer would cultivate trees and diligently practice forest conservation to ensure its own continued existence and success. Far too few companies are this proactive in both customer service and customer conservation. Although this comment should not be seen as an endorsement of Walmart’s tactics, it is acknowledgement of the company’s business acumen and strategic use of data.

As insurance companies move forward using big data to mitigate risks and increase their business, they too should diligently watch for the rise of new disruptive competitors similar to those that have risen in other areas of financial services such as in lending. The one thing that is certain about big data is that it is disrupting and reshaping every industry.

SUMMARY

In this chapter you learned that banks have plenty of data on hand and more at their disposal. So the problem is not the lack of data but in figuring out how to use it and for what purposes. You also discovered that, surprisingly, some banks are using big data successfully but fail to recognize that is what they are doing. By not recognizing these efforts for what they are, the banks fail to grasp and leverage lessons learned in big data projects.

You learned that financial institutions should first look to see if they already have projects in motion that are using copious amounts of data. If so, find and use the lessons learned within them. Otherwise, the best place to start is in any activity where data analysis is currently and routinely used. Choose one or a few of those that are in most need of improvement and then begin a pilot project or two accordingly.

Other use cases for this sector include strategic planning, new revenue stream discovery, product innovation, trading, compliance, and risk and security.

You also learned that traditional lending institutions place too much faith in outside traditional risk-assessment and data sources, namely traditional credit bureaus. Therefore the lenders are further stymied by problems found in traditional credit bureau data such as too little data, irrelevant data, outdated credit rating systems, and erroneous data.

Finally, you learned that as insurance companies move forward using big data to mitigate risks and increase their business, they too should diligently watch for the rise of new disruptive competitors similar to those that have risen in other areas of financial services such as in lending.