Chapter 1

Understanding Cybersecurity Policy and Governance

Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you should be able to do the following:

Describe the significance of cybersecurity policies.

Evaluate the role policy plays in corporate culture and civil society.

Articulate the objective of cybersecurity-related policies.

Identify the different characteristics of successful cybersecurity policies.

Define the life cycle of a cybersecurity policy.

We live in an interconnected world where both individual and collective actions have the potential to result in inspiring goodness or tragic harm. The objective of cybersecurity is to protect each of us, our economy, our critical infrastructure, and our country from the harm that can result from inadvertent or intentional misuse, compromise, or destruction of information and information systems.

The United States Department of Homeland Security defines several critical infrastructure sectors, as illustrated in Figure 1-1.

FIGURE 1-1 United States Critical Infrastructure Sectors

The United States Department of Homeland Security describes the services provided by critical infrastructure sectors as “the backbone of our nation’s economy, security, and health. We know it as the power we use in our homes, the water we drink, the transportation that moves us, the stores we shop in, and the communication systems we rely on to stay in touch with friends and family. Overall, there are 16 critical infrastructure sectors that compose the assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof.”1

FYI: National Security

Presidential Policy Directive 7 — Protecting Critical Infrastructure (2003) established a national policy that required federal departments and agencies to identify and prioritize United States critical infrastructure and key resources and to protect them from physical and cyber terrorist attacks. The directive acknowledged that it is not possible to protect or eliminate the vulnerability of all critical infrastructure and key resources throughout the country, but that strategic improvements in security can make it more difficult for attacks to succeed and can lessen the impact of attacks that may occur. In addition to strategic security enhancements, tactical security improvements can be rapidly implemented to deter, mitigate, or neutralize potential attacks.

Ten years later, in 2013, Presidential Policy Directive 21—Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience broadened the effort to strengthen and maintain secure, functioning, and resilient critical infrastructure by recognizing that this endeavor is a shared responsibility among the federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial entities, as well as public and private owners and operators of critical infrastructure.

Then, four years later, in 2017, Presidential Executive Order on Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure was implemented by President Trump. It is worth highlighting that large policy changes with wide-ranging effects have been implemented through executive orders, although most do not affect all government sectors. In the case of cybersecurity, however, this executive order requires that all federal agencies adopt the Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The framework was developed by experts with input from the private sector, as well as the public, and is described as “a common language for understanding, managing, and expressing cybersecurity risk both internally and externally.”

Policy is the seminal tool used to protect both our critical infrastructure and our individual liberties. The role of policy is to provide direction and structure. Policies are the foundation of companies’ operations, a society’s rule of law, or a government’s posture in the world. Without policies, we would live in a state of chaos and uncertainty. The impact of a policy can be positive or negative. The hallmark of a positive policy is one that supports our endeavors, responds to a changing environment, and potentially creates a better world.

In this chapter, we explore policies from a historical perspective, talk about how humankind has been affected, and learn how societies have evolved using policies to establish order and protect people and resources. We apply these concepts to cybersecurity principles and policies. Then we discuss in detail the seven characteristics of an effective cybersecurity policy. We acknowledge the influence of government regulation on the development and adoption of cybersecurity policies and practices. Last, we will tour the policy life cycle.

Information Security vs. Cybersecurity Policies

Many individuals confuse traditional information security with cybersecurity. In the past, information security programs and policies were designed to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data within the confinement of an organization. Unfortunately, this is no longer sufficient. Organizations are rarely self-contained, and the price of interconnectivity is exposure to attack. Every organization, regardless of size or geographic location, is a potential target. Cybersecurity is the process of protecting information by preventing, detecting, and responding to attacks.

Cybersecurity programs and policies recognize that organizations must be vigilant, resilient, and ready to protect and defend every ingress and egress connection as well as organizational data wherever it is stored, transmitted, or processed. Cybersecurity programs and policies expand and build upon traditional information security programs, but also include the following:

Cyber risk management and oversight

Threat intelligence and information sharing

Third-party organization, software, and hardware dependency management

Incident response and resiliency

Looking at Policy Through the Ages

Sometimes an idea seems more credible if we begin with an understanding that it has been around for a long time and has withstood the test of time. Since the beginning of social structure, people have sought to form order out of perceived chaos and to find ways to sustain ideas that benefit the advancement and improvement of a social structure. The best way we have found yet is in recognizing common problems and finding ways to avoid causing or experiencing them in our future endeavors. Policies, laws, codes of justice, and other such documents came into existence almost as soon as alphabets and the written word allowed them. This does not mean that before the written word there were no policies or laws. It does mean that we have no reference to spoken policy known as “oral law,” so we will confine our discussion to written documents we know existed and still exist.

We are going to look back through time at some examples of written policies that had and still have a profound effect on societies across the globe, including our own. We are not going to concern ourselves with the function of these documents. Rather, we begin by noting the basic commonality we can see in why and how they were created to serve a larger social order. Some are called laws, some codes, and some canons, but what they all have in common is that they were created out of a perceived need to guide human behavior in foreseeable circumstances, and even to guide human behavior when circumstances could not be or were not foreseeable. Equal to the goal of policy to sustain order and protection is the absolute requirement that our policy be changeable in response to dynamic conditions.

Policy in Ancient Times

Let’s start by going back in time over 3,300 years. Examples of written policy are still in existence, such as the Torah and other religious and historical documentation. For those of the Jewish faith, the Torah is the Five Books of Moses. Christians refer to the Torah as the Old Testament of the Bible. The Torah can be divided into three categories—moral, ceremonial, and civil. If we put aside the religious aspects of this work, we can examine the Torah’s importance from a social perspective and its lasting impact on the entire world. The Torah articulated a codified social order. It contains rules for living as a member of a social structure. The rules were and are intended to provide guidance for behavior, the choices people make, and their interaction with each other and society as a whole. Some of the business-related rules of the Torah include the following:

Not to use false weights and measures

Not to charge excessive interest

To be honest in all dealings

To pay wages promptly

To fulfill promises to others

What is worth recognizing is the longevity and overall impact of these “examples of policies.” The Torah has persisted for thousands of years, even driving cultures throughout time. These benefits of “a set of policies” are not theoretical, but are real for a very long period of time.

The United States Constitution as a Policy Revolution

Let’s look at a document you may be a little more familiar with: the Constitution of the United States of America. The Constitution is a collection of articles and amendments that provide a framework for the American government and define citizens’ rights. The articles themselves are very broad principles that recognize that the world will change. This is where the amendments play their role as additions to the original document. Through time, these amendments have extended rights to more and more Americans and have allowed for circumstances our founders could not have foreseen. The founders wisely built in to the framework of the document a process for changing it while still adhering to its fundamental tenets. Although it takes great effort to amend the Constitution, the process begins with an idea, informed by people’s experience, when they see a need for change. We learn some valuable lessons from the Constitution—most important is that our policies need to be dynamic enough to adjust to changing environments.

The Constitution and the Torah were created from distinct environments, but they both had a similar goal: to serve as rules as well as to guide our behavior and the behavior of those in power. Though our cybersecurity policies may not be used for such lofty purposes as the Constitution and the Torah, the need for guidance, direction, and roles remains the same.

Policy Today

We began this chapter with broad examples of the impact of policy throughout history. Let’s begin to focus on the organizations for which we will be writing our cybersecurity policies—namely, profit, nonprofit, and not-for-profit businesses, government agencies, and institutions. The same circumstances that led us to create policies for social culture exist for our corporate culture as well.

Guiding Principles

Corporate culture can be defined as the shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterize a company, corporation, or institution. Guiding principles set the tone for a corporate culture. Guiding principles synthesize the fundamental philosophy or beliefs of an organization and reflect the kind of company that an organization seeks to be.

Not all guiding principles, and hence corporate cultures, are good. In fact, there are companies for whom greed, exploitation, and contempt are unspoken-yet-powerful guiding principles. You may recall the deadly April 24, 2013, garment factory collapse in Bangladesh, where 804 people were confirmed dead and more than 2,500 injured.2 This is a very sad example of a situation in which the lives of many were knowingly put at risk for the sake of making money.

Culture can be shaped both informally and formally. For instance, cultures can be shaped informally by how individuals are treated within an organization. It can also be shaped formally by written policies. An organization may have a policy that could allow and value employee input, but the actual organization may never provide an opportunity for employees to provide any input. In this case, you may have a great policy, but if it is not endorsed and enacted, it is useless.

Corporate Culture

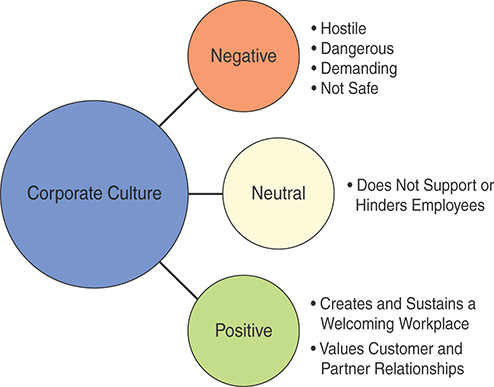

Corporate cultures are often classified by how corporations treat their employees and their customers. The three classifications are negative, neutral, and positive, as illustrated in Figure 1-2.

FIGURE 1-2 Corporate Culture Types

A negative classification is indicative of a hostile, dangerous, or demeaning environment. Workers do not feel comfortable and may not be safe; customers are not valued and may even be cheated. A neutral classification means that the business neither supports nor hinders its employees; customers generally get what they pay for. A positive classification is awarded to businesses that strive to create and sustain a welcoming workplace, truly value the customer relationship, partner with their suppliers, and are responsible members of their community.

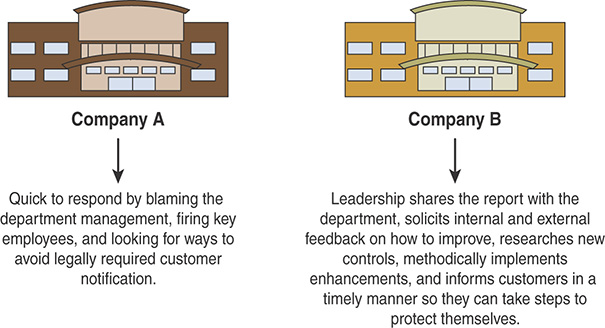

Let’s consider a tale of two companies. Both companies experience a data breach that exposes customer information; both companies call in experts to help determine what happened. In both cases, the investigators determine that the data-protection safeguards were inadequate and that employees were not properly monitoring the systems. The difference between these two companies is how they respond to and learn from the incident, as illustrated in Figure 1-3.

FIGURE 1-3 Corporate Culture Types

As shown in Figure 1-3, Company A is quick to respond by blaming the department management, firing key employees, and looking for ways to avoid legally required customer notification. Company B leadership shares the report with the department, solicits internal and external feedback on how to improve, researches new controls, methodically implements enhancements, and informs customers in a timely manner so they can take steps to protect themselves.

A positive corporate culture that focuses on protecting internal and customer information, solicits input, engages in proactive education, and allocates resources appropriately makes a strong statement that employees and customers are valued. In these organizations, policy is viewed as an investment and a competitive differentiator for attracting quality employees and customers.

In Practice

The Philosophy of Honoring the Public Trust

Each of us willingly shares a great deal of personal information with organizations that provide us service, and we have an expectation of privacy. Online, we post pictures, profiles, messages, and much more. We disclose and discuss our physical, emotional, mental, and familial issues with health professionals. We provide confidential financial information to accountants, bankers, financial advisors, and tax preparers. The government requires that we provide myriad data throughout our life, beginning with birth certificates and ending with death certificates. On occasion, we may find ourselves in situations where we must confide in an attorney or clergy. In each of these situations, we expect the information we provide will be protected from unauthorized disclosure, not be intentionally altered, and used only for its intended purpose. We also expect that the systems used to provide the service will be available. The philosophy of honoring the public trust instructs us to be careful stewards of the information with which we have been entrusted. It is one of the main objectives of organizations that truly care about those they serve. As you plan your career, consider your potential role in honoring the public trust.

Cybersecurity Policy

The role of policy is to codify guiding principles, shape behavior, provide guidance to those who are tasked with making present and future decisions, and serve as an implementation roadmap. A cybersecurity policy is a directive that defines how the organization is going to protect its information assets and information systems, ensure compliance with legal and regulatory requirements, and maintain an environment that supports the guiding principles.

The objective of a cybersecurity policy and corresponding program is to protect the organization, its employees, its customers, and its vendors and partners from harm resulting from intentional or accidental damage, misuse, or disclosure of information, as well as to protect the integrity of the information and ensure the availability of information systems.

FYI: Cyber What?

The word “cyber” is nothing new. Since the early 1990s, the prefix “cyber”3 is defined as involving computers or computer networks. Affixed to the terms crime, terrorism, and warfare, cyber means that computer resources or computer networks such as the Internet are used to commit the action.

Richard Clarke, former cybersecurity adviser to Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, commented that “the difference between cybercrime, cyber-espionage, and cyber-war is a couple of keystrokes. The same technique that gets you in to steal money, patented blueprint information, or chemical formulas is the same technique that a nation-state would use to get in and destroy things.”

What Are Assets?

Information is data with context or meaning. An asset is a resource with value. As a series of digits, the string 123456789 has no discernible value. However, if those same numbers represented a social security number (123-45-6789) or a bank account number (12-3456789), they would have both meaning and value. Information asset is the term applied to the information that an organization uses to conduct its business. Examples include customer data, employee records, financial documents, business plans, intellectual property, IT information, reputation, and brand. Information assets may be protected by law or regulation (for example, patient medical history), considered internally confidential (for example, employee reviews and compensation plans), or even publicly available (for example, website content). Information assets are generally stored in digital or print format; however, it is possible to extend our definition to institutional knowledge.

In most cases, organizations establish cybersecurity policies following the principles of defense-in-depth. If you are a cybersecurity expert, or even an amateur, you probably already know that when you deploy a firewall or an intrusion prevention system (IPS) or install antivirus or advanced malware protection on your machine, you cannot assume you are now safe and secure. A layered and cross-boundary “defense-in-depth” strategy is what is required to protect network and corporate assets. The primary benefit of a defense-in-depth strategy is that even if a single control (such as a firewall or IPS) fails, other controls can still protect your environment and assets. The concept of defense-in-depth is illustrated in Figure 1-4.

FIGURE 1-4 Defense-in-Depth

The following are the layers illustrated in Figure 1-4 (starting from the left):

Administrative (nontechnical) activities, such as appropriate security policies and procedures, risk management, and end-user and staff training.

Physical security, including cameras, physical access control (such as badge readers, retina scanners, and fingerprint scanners), and locks.

Perimeter security, including firewalls, IDS/IPS devices, network segmentation, and VLANs.

Network security best practices, such as routing protocol authentication, control plane policing (CoPP), network device hardening, and so on.

Host security solutions, such as advanced malware protection (AMP) for endpoints, antiviruses, and so on.

Application security best practices, such as application robustness testing, fuzzing, defenses against cross-site scripting (XSS), cross-site request forgery (CSRF) attacks, SQL injection attacks, and so on.

The actual data traversing the network. You can employ encryption at rest and in transit to protect data.

Each layer of security introduces complexity and latency while requiring that someone manage it. The more people are involved, even in administration, the more attack vectors you create, and the more you distract your people from possibly more important tasks. Employ multiple layers, but avoid duplication—and use common sense.

Globally, governments and private organizations are moving beyond the question of whether to use cloud computing. Instead they are focusing on how to become more secure and effective when adopting the cloud. Cloud computing represents a drastic change when compared to traditional computing. The cloud enables organizations of any size to do more and faster. The cloud is unleashing a whole new generation of transformation, delivering big data analytics and empowering the Internet of Things; however, understanding how to make the right policy, operational, and procurement decisions can be difficult. This is especially true with cloud adoption, because it has the potential to alter the paradigm of how business is done and who owns the task of creating and enforcing such policies.

In addition, it can also bring confusion about appropriate legislative frameworks, and specific security requirements of different data assets risk slowing government adoption. Whether an organization uses public cloud services by default or as a failover option, the private sector and governments must be confident that, if a crisis does unfold, the integrity, confidentiality, and availability of their data and essential services will remain intact. Each cloud provider will have its own policies, and each customer (organization buying cloud services) will also have its own policies. Nowadays, this paradigm needs to be taken into consideration when you are building your cybersecurity program and policies.

Successful Policy Characteristics

Successful policies establish what must be done and why it must be done, but not how to do it. Good policy has the following seven characteristics:

Endorsed: The policy has the support of management.

Relevant: The policy is applicable to the organization.

Realistic: The policy make sense.

Attainable: The policy can be successfully implemented.

Adaptable: The policy can accommodate change.

Enforceable: The policy is statutory.

Inclusive: The policy scope includes all relevant parties.

Taken together, the characteristics can be thought of as a policy pie, with each slice being equally important, as illustrated in Figure 1-5.

FIGURE 1-5 The Policy Pie

Endorsed

We have all heard the saying “Actions speak louder than words.” For a cybersecurity policy to be successful, leadership must not only believe in the policy, they must also act accordingly by demonstrating an active commitment to the policy by serving as role models. This requires visible participation and action, ongoing communication and championing, investment, and prioritization.

Consider this situation: Company A and Company B both decide to purchase mobile phones for management and sales personnel. By policy, both organizations require strong, complex email passwords. At both organizations, IT implements the same complex password policy on the mobile phone that is used to log in to their webmail application. Company A’s CEO is having trouble using the mobile phone, and he demands that IT reconfigure his phone so he doesn’t have to use a password. He states that he is “too important to have to spend the extra time typing in a password, and besides none of his peers have to do so.” Company B’s CEO participates in rollout training, encourages employees to choose strong passwords to protect customer and internal information, and demonstrates to his peers the enhanced security, including a wipe feature after five bad password attempts.

Nothing will doom a policy quicker than having management ignore or, worse, disobey or circumvent it. Conversely, visible leadership and encouragement are two of the strongest motivators known to humankind.

Policies can also pertain to personal or customer data management, security vulnerability policies, and others.

Let’s look at one of the biggest breaches of recent history, the Equifax breach. On September 2017, Equifax was breached, leaving millions of personal records exposed to attackers. The exposed data was mostly of customers in the United States of America. On the other hand, Equifax has personal data management policies that extend to other countries, such as the United Kingdom. This policy can be found at: http://www.equifax.com/international/uk/documents/Equifax_Personal_Data_Management_Policy.pdf.

As stated in that document, there are many regulations that enforce organizations such as Equifax to publicly document these policies and specify what they do to protect customer data:

“While this is not an exhaustive list, the following regulations (as amended from time to time) are directly applicable to how Equifax manages personal data as a credit reference agency:

(a) Data Protection Act 1998

(b) Consumer Credit (Credit Reference Agency) Regulations 2000

(c) Data Protection (Subject Access) (Fees and Miscellaneous Provisions) Regulations 2000

(d) Consumer Credit Act 1974

(e) The Consumer Credit (EU Directive) Regulations 2010

(f) The Representation of the People (England and Wales) Regulations 2001”

Relevant

Strategically, the cybersecurity policy must support the guiding principles and goals of the organization. Tactically, it must be relevant to those who must comply. Introducing a policy to a group of people who find nothing recognizable in relation to their everyday experience is a recipe for disaster.

Consider this situation: Company A’s CIO attends a seminar on the importance of physical access security. At the seminar, they distribute a “sample” policy template. Two of the policy requirements are that exterior doors remain locked at all times and that every visitor be credentialed. This may sound reasonable, until you consider that most Company A locations are small offices that require public accessibility. When the policy is distributed, the employees immediately recognize that the CIO does not have a clue about how they operate.

Policy writing is a thoughtful process that must take into account the environment. If policies are not relevant, they will be ignored or, worse, dismissed as unnecessary, and management will be perceived as being out of touch.

Realistic

Think back to your childhood to a time you were forced to follow a rule you did not think made any sense. The most famous defense most of us were given by our parents in response to our protests was, “Because I said so!” We can all remember how frustrated we became whenever we heard that statement, and how it seemed unjust. We may also remember our desire to deliberately disobey our parents—to rebel against this perceived tyranny. In very much the same way, policies will be rejected if they are not realistic. Policies must reflect the reality of the environment in which they will be implemented.

Consider this situation: Company A discovers that users are writing down their passwords on sticky notes and putting the sticky notes on the underside of their keyboard. This discovery is of concern because multiple users share the same workstation. In response, management decides to implement a policy that prohibits employees from writing down their passwords. Turns out that each employee uses at least six different applications, and each requires a separate login. What’s more, on average, the passwords change every 90 days. One can imagine how this policy might be received. More than likely, users will decide that getting their work done is more important than obeying this policy and will continue to write down their passwords, or perhaps they will decide to use the same password for every application. To change this behavior will take more than publishing a policy prohibiting it; leadership needs to understand why employees were writing down their passwords, make employees aware of the dangers of writing down their passwords, and most importantly provide alternative strategies or aids to remember the passwords.

If you engage constituents in policy development, acknowledge challenges, provide appropriate training, and consistently enforce policies, employees will be more likely to accept and follow the policies.

Attainable

Policies should be attainable and should not require impossible tasks and requirements for the organizations and its stakeholders. If you assume that the objective of a policy is to advance the organization’s guiding principles, you can also assume that a positive outcome is desired. A policy should never set up constituents for failure; rather, it should provide a clear path for success.

Consider this situation: To contain costs and enhance tracking, Company A’s management adopted a procurement policy that purchase orders must be sent electronically to suppliers. They set a goal of 80% electronic fulfillment by the end of the first year and announced that regional offices that do not meet this goal will forfeit their annual bonus. In keeping with existing cybersecurity policy, all electronic documents sent externally that include proprietary company information must be sent using the secure file transfer application. The problem is that procurement personnel despise the secure file transfer application because it is slow and difficult to use. Most frustrating of all, it is frequently offline. That leaves them three choices: depend on an unstable system (not a good idea), email the purchase order (in violation of policy), or continue mailing paper-based purchase orders (and lose their bonus).

It is important to seek advice and input from key people in every job role to which the policies apply. If unattainable outcomes are expected, people are set up to fail. This will have a profound effect on morale and will ultimately affect productivity. Know what is possible.

Adaptable

To thrive and grow, businesses must be open to changes in the market and be willing to take measured risks. A static set-in-stone cybersecurity policy is detrimental to innovation. Innovators are hesitant to talk with security, compliance, or risk departments for fear that their ideas will immediately be discounted as contrary to policy or regulatory requirement. “Going around” security is understood as the way to get things done. The unfortunate result is the introduction of products or services that may put the organization at risk.

Consider this situation: Company A and Company B are in a race to get their mobile app to market. Company A’s programming manager instructs her team to keep the development process secret and not to involve any other departments, including security and compliance. She has 100% faith in her team and knows that without distractions they can beat Company B to market. Company B’s programming manager takes a different tack. She demands that security requirements be defined early in the software development cycle. In doing so, her team identifies a policy roadblock. They have determined that they need to develop custom code for the mobile app, but the policy requires that “standard programming languages be used.” Working together with the security officer, the programming manager establishes a process to document and test the code in such a way that it meets the intent of the policy. Management agrees to grant an exception and to review the policy in light of new development methodologies.

Company A does get to market first. However, its product is vulnerable to exploit, puts its customers at risk, and ultimately gets bad press. Instead of moving on to the next project, the development team will need to spend time rewriting code and issuing security updates. Company B gets to market a few months later. It launches a functional, stable, and secure app.

An adaptable cybersecurity policy recognizes that cybersecurity is not a static, point-in-time endeavor but rather an ongoing process designed to support the organizational mission. The cybersecurity program should be designed in such a way that participants are encouraged to challenge conventional wisdom, reassess the current policy requirements, and explore new options without losing sight of the fundamental objective. Organizations that are committed to secure products and services often discover it to be a sales enabler and competitive differentiator.

Enforceable

Enforceable means that administrative, physical, or technical controls can be put in place to support the policy, that compliance can be measured, and, if necessary, appropriate sanctions applied.

Consider this scenario: Company A and Company B both have a policy stating that Internet access is restricted to business use only. Company A does not have any controls in place to restrict access; instead, the company leaves it up to the user to determine “business use.” Company B implements web-filtering software that restricts access by site category and reviews the filtering log daily. In conjunction with implementing the policy, Company B conducts a training session explaining and demonstrating the rationale for the policy with an emphasis on disrupting the malware delivery channel.

A workstation at Company A is infected with malware. It is determined that the malware came from a website that the workstation user accessed. Company A’s management decides to fire the user for “browsing” the Web. The user files a protest claiming that the company has no proof that it wasn’t business use, that there was no clear understanding of what “business use” meant, and besides, everyone (including his manager) is always surfing the Web without consequence.

A user at Company B suspects something is wrong when multiple windows start opening while he is at a “business use” website. He immediately reports the suspicious activity. His workstation is immediately quarantined and examined for malware. Company B’s management investigates the incident. The logs substantiate the user’s claim that the access was inadvertent. The user is publicly thanked for reporting the incident.

If a rule is broken and there is no consequence, then the rule is essentially meaningless. However, there must be a fair way to determine if a policy was violated, which includes evaluating the organizational support of the policy. Sanctions should be clearly defined and commensurate with the associated risk. A clear and consistent process should be in place so that all similar violations are treated in the same manner.

You should also develop reports and metrics that can be evaluated on an ongoing basis to determine if your policy is effective, who is abiding and conforming, who is violating it, and why it is being violated. Is it hindering productivity? Is it too hard to understand or follow?

Inclusive

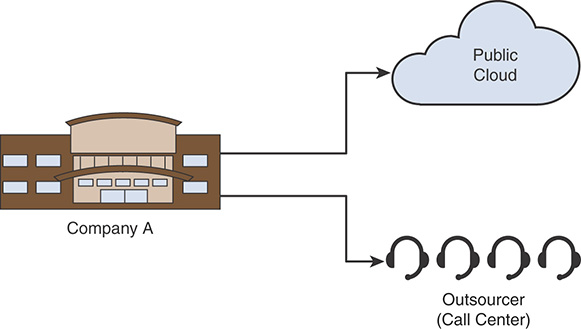

It is important to include external parties in our policy thought process. It used to be that organizations had to be concerned about information and systems housed only within their walls. That is no longer the case. Data (and the systems that store, transmit, and process it) are now widely and globally distributed. For example, an organization can put information in a public cloud (such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, and so on) and may also have outsourcers that can also handle sensitive information. For example, in Figure 1-6, Company A is supported by an outsourcing company that provides technical assistance services (call center) to its customers. In addition, it uses cloud services from a cloud provider.

FIGURE 1-6 Outsourcing and Cloud Services

Organizations that choose to put information in or use systems in “the cloud” may face the additional challenge of having to assess and evaluate vendor controls across distributed systems in multiple locations. The reach of the Internet has facilitated worldwide commerce, which means that policies may have to consider an international audience of customers, business partners, and employees. The trend toward outsourcing and subcontracting requires that policies be designed in such a way as to incorporate third parties. Cybersecurity policies must also consider external threats such as unauthorized access, vulnerability exploits, intellectual property theft, denial of service attacks, and hacktivism done in the name of cybercrime, terrorism, and warfare.

A cybersecurity policy must take into account the factors illustrated in Figure 1-7.

FIGURE 1-7 Cybersecurity Policy Considerations

If the cybersecurity policy is not written in a way that is easy to understand, it can also become useless. In some cases, policies are very difficult to understand. If they are not clear and easy to understand, they will not be followed by employees and other stakeholders. A good cybersecurity policy is one that can positively affect the organization, its shareholders, employees, and customers, as well as the global community.

What Is the Role of Government?

In the previous section, we peeked into the world of Company A and Company B and found them to be very different in their approach to cybersecurity. In the real world, this is problematic. Cybersecurity is complex, and weaknesses in one organization can directly affect another. At times, government intervention is required to protect its critical infrastructure and its citizens. Intervention with the purpose of either restraining or causing a specific set of uniform actions is known as regulation. Legislation is another term meaning statutory law. These laws are enacted by a legislature (part of the governing body of a country, state, province, or even towns). Legislation can also mean the process of making the law. Legislation and regulation are two terms that often confuse people that are not well-versed in law terminologies.

Regulations can be used to describe two underlying items:

A process of monitoring and enforcing legislation

A document or set of documents containing rules that are part of specific laws or government policies

Law is one of the most complicated subjects and has various different terms and words that often mean different things in different contexts. Legislation and regulation should not be confused; they are completely different from each other.

In the 1990s, two major federal legislations were introduced with the objective of protecting personal financial and medical records:

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), also known as the Financial Modernization Act of 1999, Safeguards Rule

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA)

On November 12, 1999, President Clinton signed the GLB Act (GLBA) into law. The purpose of the act was to reform and modernize the banking industry by eliminating existing barriers between banking and commerce. The act permitted banks to engage in a broad range of activities, including insurance and securities brokering, with new affiliated entities. Lawmakers were concerned that these activities would lead to an aggregation of customer financial information and significantly increase the risk of identity theft and fraud. Section 501B of the legislation, which went into effect May 23, 2003, required that companies that offer consumers financial products or services, such as loans, financial or investment advice, or insurance4, ensure the security and confidentiality of customer records and information, protect against any anticipated threats or hazards to the security or integrity of such records, and protect against unauthorized access to or use of such records or information that could result in substantial harm or inconvenience to any customer. GLBA requires financial institutions and other covered entities to develop and adhere to a cybersecurity policy that protects customer information and assigns responsibility for the adherence to the Board of Directors. Enforcement of GLBA was assigned to federal oversight agencies, including the following organizations:

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

Federal Reserve

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)

National Credit Union Agency (NCUA)

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

Note

In Chapter 13, “Regulatory Compliance for Financial Institutions,” we examine the regulations applicable to the financial sector, with a focus on the cybersecurity interagency guidelines establishing cybersecurity standards, the FTC Safeguards Act, Financial Institution Letters (FILs), and applicable supplements.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

Likewise, the HIPAA Security Rule established a national standard to protect individuals’ electronic personal health information (known as ePHI) that is created, received, used, or maintained by a covered entity, which includes health-care providers and business associates. The Security Rule requires appropriate administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and security of electronic protected health information. Covered entities are required to publish comprehensive cybersecurity policies that communicate in detail how information is protected. The legislation, while mandatory, did not include a stringent enforcement process. However, in 2012, one of the provisions of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) assigned audit and enforcement responsibility to the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Civil Rights (HHS-OCR) and gave state attorneys general the power to file suit over HIPAA violations in their jurisdiction.

Note

In Chapter 14, “Regulatory Compliance for the Health-Care Sector,” we examine the components of the original HIPAA Security Rule and the subsequent HITECH Act and the Omnibus Rule. We discuss the policies, procedures, and practices that entities need to implement to be HIPAA-compliant.

In Practice

Protecting Your Student Record

The privacy of your student record is governed by a federal law known as FERPA, which stands for the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974. The law states that an educational institution must establish a written institutional policy to protect confidentiality of student education records and that students must be notified of their rights under the legislation. Privacy highlights of the policy include the requirement that schools must have written permission from the parent or eligible students (age 18 and older) in order to release any information from a student’s education record. Schools may disclose, without consent, “directory” information, such as a student’s name, address, telephone number, date and place of birth, honors and awards, and dates of attendance. However, schools must tell parents and eligible students about directory information and allow parents and eligible students a reasonable amount of time to request that the school not disclose directory information about them.

States, Provinces, and Local Governments as Leaders

Local governments (states, provinces or even towns) can lead the way in a nation or region. For example, historically the United States Congress failed repeatedly to establish a comprehensive national security standard for the protection of digital nonpublic personally identifiable information (NPPI), including notification of breach or compromise requirements. In the absence of federal legislation, states have taken on the responsibility. On July 1, 2003, California became the first state to enact consumer cybersecurity notification legislation. SB 1386: California Security Breach Information Act requires a business or state agency to notify any California resident whose unencrypted personal information was acquired, or reasonably believed to have been acquired, by an unauthorized person.

The law defines personal information as: “any information that identifies, relates to, describes, or is capable of being associated with, a particular individual, including, but not limited to, his or her name, signature, social security number, physical characteristics or description, address, telephone number, passport number, driver’s license or state identification card number, insurance policy number, education, employment, employment history, bank account number, credit card number, debit card number, or any other financial information, medical information, or health insurance information.”

Subsequently, 48 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands have enacted legislation requiring private or governmental entities to notify individuals of security breaches of information involving personally identifiable information.

Note

In Chapter 11, “Cybersecurity Incident Response,” we discuss the importance of incident response capability and how to comply with the myriad of state data-breach notification laws.

Another example is when Massachusetts became the first state in the United States to require the protection of personally identifiable information of Massachusetts residents. 201 CMR 17: Standards for the Protection of Personal Information of Residents of the Commonwealth establishes minimum standards to be met in connection with the safeguarding of personal information contained in both paper and electronic records and mandates a broad set of safeguards, including security policies, encryption, access control, authentication, risk assessment, security monitoring, and training. Personal information is defined as a Massachusetts resident’s first name and last name, or first initial and last name, in combination with any one or more of the following: social security number, driver’s license number or state-issued identification card number, financial account number, or credit or debit card number. The provisions of this regulation apply to all persons who own or license personal information about a resident of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

The New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) has become increasingly concerned about the number of cybersecurity incidents affecting financial services organizations. The NY DFS was also concerned with the potential risks posed to the industry at large (this includes multinational companies that could provide financial services in the United States). In late 2016, NY DFS proposed new requirements relating to cybersecurity for all DFS-regulated entities. On February 16, 2017, the finalized NY DFS cybersecurity requirements (23 NYCRR 500) were posted to the New York State Register. The NYCRR is published at the following link:

http://www.dfs.ny.gov/legal/regulations/adoptions/dfsrf500txt.pdf

Financial services organizations will be required to prepare and submit to the superintendent a Certification of Compliance with the NY DFS Cybersecurity Regulations annually.

Regulatory compliance is a powerful driver for many organizations. There are industry sectors that recognize the inherent operational, civic, and reputational benefit of implementing applicable controls and safeguards. Two of the federal regulations mentioned earlier in this chapter—GLBA and HIPAA—were the result of industry and government collaboration. The passage of these regulations forever altered the cybersecurity landscape.

Additional Federal Banking Regulations

In recent years, three federal banking regulators issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking for new cybersecurity regulations for large financial institutions:

The Federal Reserve Bank (FRB)

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

What is a large financial institution? These are institutions with consolidated assets of $50 billion and critical financial infrastructure. This framework was intended to result in rules to address the type of serious “cyber incident or failure” that could “impact the safety and soundness” of not just the financial institution that is the victim of a cyberattack, but the soundness of the financial system and markets overall. After these initial attempts, the FRB has archived and documented all regulation-related letters and policies at the following website:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/srletters.htm

You will learn more about federal and state regulatory requirements and their relationship to cybersecurity policies and practices in Chapters 13, 14, and 15.

Government Cybersecurity Regulations in Other Countries

These types of regulations are not only in the United States. There are several regulatory bodies in other countries, especially in Europe. The following are the major regulation entities within the European Union (EU):

European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA): An agency initially organized by the Regulation (EC) No 460/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 March 2004 for the purpose of raising network and information security (NIS), awareness for all inter-network operations within the EU. Currently, ENISA currently runs under Regulation (EU) No 526/2013, which has replaced the original regulation in 2013. Their website includes all the recent information about policies, regulations, and other cybersecurity-related information: https://www.enisa.europa.eu.5

Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems (the NIS Directive): The European Parliament set into policy this directive, created to maintain an overall higher level of cybersecurity in the EU.

EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Created to maintain a single standard for data protection among all member states in the EU.

The Challenges of Global Policies

One of the world’s greatest global governance challenges is to establish shared responsibility for the most intractable problems we are trying to solve around the globe. This new global environment presents several challenges for governance.

The steadily growing complexity of public policy issues makes a global policy on any topic basically impossible to attain, specifically related to cybersecurity. Decision makers in states and international organizations are having to tackle more and more issues that cut across areas of bureaucratic or disciplinary expertise and whose complexity has yet to be fully understood.

Another challenge involves legitimacy and accountability. The traditional closed-shop of intergovernmental diplomacy cannot fulfill the aspirations of citizens and transnationally organized advocacy groups who strive for greater participation in and accountability of transnational policymaking.

Cybersecurity Policy Life Cycle

Regardless of whether a policy is based on guiding principles or regulatory requirements, its success depends in large part upon how the organization approaches the tasks of policy development, publication, adoption, and review. Collectively, this process is referred to as the policy life cycle, as illustrated in Figure 1-8.

FIGURE 1-8 Cybersecurity Policy Life Cycle

The activities in the cybersecurity policy life cycle described in Figure 1-8 will be similar among different organizations. On the other hand, the mechanics will differ depending on the organization (corporate vs. governmental) and also depending on specific regulations.

The responsibilities associated with the policy life cycle process are distributed throughout an organization as outlined in Table 1-1. Organizations that understand the life cycle and take a structured approach will have a much better chance of success. The objective of this section is to introduce you to the components that make up the policy life cycle. Throughout the text, we examine the process as it relates to specific cybersecurity policies.

TABLE 1-1 Cybersecurity Policy Life Cycle Responsibilities

Position |

Develop |

Publish |

Adopt |

Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Board of Directors and/or Executive Management |

Communicate guiding principles. Authorize policy. |

Champion the policy. |

Lead by example. |

Reauthorize or approve retirement. |

Operational Management |

Plan, research, write, vet, and review. |

Communicate, disseminate, and educate. |

Implement, evaluate, monitor, and enforce. |

Provide feedback and make recommendations. |

Compliance Officer |

Plan, research, contribute, and review. |

Communicate, disseminate, and educate. |

Evaluate. |

Provide feedback and make recommendations. |

Auditor |

|

|

Monitor. |

|

Policy Development

Even before setting pen to paper, considerable thought and effort need to be put into developing a policy. After the policy is written, it still needs to go through an extensive review and approval process. There are six key tasks in the development phase: planning, researching, writing, vetting, approving, and authorizing.

The seminal planning task should identify the need for and context of the policy. Policies should never be developed for their own sake. There should always be a reason. Policies may be needed to support business objectives, contractual obligations, or regulatory requirements. The context could vary from the entire organization to a specific subset of users. In Chapters 4 through 12, we identify the reasons for specific policies.

Policies should support and be in agreement with relevant laws, obligations, and customs. The research task focuses on defining operational, legal, regulatory, or contractual requirements and aligning the policy with the aforementioned. This objective may sound simple, but in reality is extremely complex. Some regulations and contracts have very specific requirements, whereas others are extraordinarily vague. Even worse, they may contradict each other.

For example, federal regulation requires financial institutions to notify consumers if their account information has been compromised. The notification is required to include details about the breach; however, Massachusetts Law 201 CMR 17:00: Standards for the Protection of Personal Information of Residents of the Commonwealth specifically restricts the same details from being included in the notification. You can imagine the difficult in trying to comply with opposing requirements. Throughout this text, we will align policies with legal requirements and contractual obligations.

To be effective, policies must be written for their intended audience. Language is powerful and is arguably one of the most important factors in gaining acceptance and, ultimately, successful implementation. The writing task requires that the audience be identified and understood. In Chapter 2, “Cybersecurity Policy Organization, Format, and Styles,” we explore the impact of the plain writing movement on policy development.

Policies require scrutiny. The vetting task requires the authors to consult with internal and external experts, including legal counsel, human resources, compliance, cybersecurity and technology professionals, auditors, and regulators.

Because cybersecurity policies affect an entire organization, they are inherently cross-departmental. The approval task requires that the authors build consensus and support. All affected departments should have the opportunity to contribute to, review, and, if necessary, challenge the policy before it is authorized. Within each department, key people should be identified, sought out, and included in the process. Involving them will contribute to the inclusiveness of the policy and, more importantly, may provide the incentive for them to champion the policy.

The authorization task requires that executive management or an equivalent authoritative body agree to the policy. Generally, the authority has oversight responsibilities and can be held legally liable. Both GLBA and HIPAA require written cybersecurity policies that are Board-approved and subject to at least annual review. Boards of Directors are often composed of experienced, albeit nontechnical, business people from a spectrum of industry sectors. It is helpful to know who the Board members are, and their level of understanding, so that policies are presented in a meaningful way.

Policy Publication

After you have the “green light” from the authority, it is time to publish and introduce the policy to the organization as a whole. This introduction requires careful planning and execution because it sets the stage for how well the policy will be accepted and followed. There are three key tasks in the publication phase: communication, dissemination, and education.

The objective of the communication task is to deliver the message that the policy or policies are important to the organization. To accomplish this task, visible leadership is required. There are two distinct types of leaders in the world: those who see leadership as a responsibility and those who see it as a privilege.

Leaders who see their role as a responsibility adhere to all the same rules they ask others to follow. “Do as I do” is an effective leadership style, especially in relation to cybersecurity. Security is not always convenient, and it is crucial for leadership to participate in the cybersecurity program by adhering to its policies and setting the example.

Leaders who see their role as a privilege have a powerful negative impact: “Do as I say, not as I do.” This leadership style will do more to undermine a cybersecurity program than any other single force. As soon as people learn that leadership is not subject to the same rules and restrictions, policy compliance and acceptance will begin to erode.

Invariably, the organizations in which leadership sets the example by accepting and complying with their own policies have fewer cybersecurity-related incidents. When incidents do occur, they are far less likely to cause substantial damage. When the leadership sets a tone of compliance, the rest of the organization feels better about following the rules, and they are more active in participating.

When a policy is not consistently adopted throughout the organization, it is considered to be inherently flawed. Failure to comply is a point of weakness that can be exploited. In Chapter 4, “Governance and Risk Management,” we examine the relationship between governance and security.

Disseminating the policy simply means making it available. Although the task seems obvious, it is mind-boggling how many organizations store their policies in locations that make them, at best, difficult to locate and, at worst, totally inaccessible. Policies should be widely distributed and available to their intended audience. This does not mean that all policies should be available to everyone, because there may be times when certain policies contain confidential information that should be made available only on a restricted or need-to-know basis. Regardless, policies should be easy to find for those who are authorized to view them.

Companywide training and education build culture. When people share experiences, they are drawn together; they can reinforce one another’s understanding of the subject matter and therefore support whatever initiative the training was intended to introduce. Introducing cybersecurity policies should be thought of as a teaching opportunity with the goal of raising awareness and giving each person a tangible connection to the policy objective. Initial education should be coupled with ongoing awareness programs designed to reinforce the importance of policy-driven security practices.

Multiple factors contribute to an individual’s decision to comply with a rule, policy, or law, including the chance of being caught, the reward for taking the risk, and the consequences. Organizations can influence individual decision making by creating direct links between individual actions, policy, and success. Creating a culture of compliance means that all participants not only recognize and understand the purpose of a policy, they also actively look for ways to champion the policy. Championing a policy means being willing to demonstrate visible leadership and to encourage and educate others. Creating a culture of cybersecurity policy compliance requires an ongoing investment in training and education, measurements, and feedback.

Note

In Chapter 6, “Human Resources Security,” we examine the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Security Awareness, Training, and Education (SETA) model.

Policy Adoption

The policy has been announced and the reasons communicated. Now the hard work of adoption starts. Successful adoption begins with an announcement and progresses through implementation, performance evaluation, and process improvement, with the ultimate goal being normative integration. For our purposes, normative integration means that the policy and corresponding implementation is expected behavior—all others being deviant. There are three key tasks in the adoption phase: implementation, monitoring, and enforcement:

Implementation is the busiest and most challenging task of all. The starting point is ensuring that everyone involved understands the intent of the policy as well as how it is to be applied. Decisions may need to be made regarding the purchase and configuration of supporting administrative, physical, and technical controls. Capital investments may need to be budgeted for. A project plan may need to be developed and resources assigned. Management and affected personnel need to be kept informed. Situations where implementation is not possible need to be managed, including a process for granting either temporary or permanent exceptions.

Post-implementation, compliance and policy effectiveness need to be monitored and reported. Mechanisms to monitor compliance range from application-generated metrics to manual audits, surveys, and interviews, as well as violation and incident reports.

Unless there is an approved exception, policies must be enforced consistently and uniformly. The same is true of violation consequences. If a policy is enforced only for certain circumstances and people, or if enforcement depends on which supervisor or manager is in charge, eventually there will be adverse consequences. When there is talk within an organization that different standards for enforcement exist, the organization is open to many cultural problems, the most severe of which involve discrimination lawsuits. The organization should analyze why infractions against a policy occur. This may highlight gaps in the policy that may need to be adjusted.

Policy Review

Change is inherent in every organization. Policies must support the guiding principles, organizational goals, and forward-facing initiatives. They must also be harmonized with regulatory requirements and contractual obligations. The two key tasks in the review phase are soliciting feedback and reauthorizing or retiring policies:

Continuing acceptance of cybersecurity policies hinges on making sure the policies keep up with significant changes in the organization or the technology infrastructure. Policies should be reviewed annually. Similar to the development phase, feedback should be solicited from internal and external sources.

Policies that are outdated should be refreshed. Policies that are no longer applicable should be retired. Both tasks are important to the overall perception of the importance and applicability of organizational directives. The outcome of the annual review should either be policy reauthorization or policy retirement. The final determination belongs with the Board of Directors or equivalent body.

Summary

In this chapter, we discussed the various roles policies play, and have played, in many forms of social structures—from entire cultures to corporations. You learned that policies are not new in the world. When its religious intent is laid aside, the Torah reads like any other secular code of law or policy. The people of that time were in desperate need of guidance in their everyday existence to bring order to their society. You learned that policies give us a way to address common foreseeable situations and guide us to make decisions when faced with them. Similar to the circumstances that brought forth the Torah 3,000 years ago, our country found itself in need of a definite structure to bring to life the ideals of our founders and make sure those ideals remained intact. The U.S. Constitution was written to fulfill that purpose and serves as an excellent example of a strong, flexible, and resilient policy document.

We applied our knowledge of historical policy to the present day, examining the role of corporate culture, specifically as it applies to cybersecurity policy. Be it societal, government, or corporate, policy codifies guiding principles, shapes behavior, provides guidance to those who are tasked with making present and future decisions, and serves as an implementation roadmap. Because not all organizations are motivated to do the right thing, and because weaknesses in one organization can directly affect another, there are times when government intervention is required. We considered the role of government policy—specifically the influence of groundbreaking federal and state legislation related to the protection of NPPI in the public and privacy sectors.

The objective of a cybersecurity policy is to protect the organization, its employees, its customers, and also its vendors and partners from harm resulting from intentional or accidental damage, misuse, or disclosure of information, as well as to protect the integrity of the information and ensure the availability of information systems. We examined in depth the seven common characteristics of a successful cybersecurity policy as well as the policy life cycle. The seven common characteristics are endorsed, relevant, realistic, attainable, adaptable, enforceable, and inclusive. The policy life cycle spans four phases: develop, publish, adopt, and review. Policies need champions. Championing a policy means being willing to demonstrate visible leadership and to encourage and educate others with the objective of creating a culture of compliance, where participants not only recognize and understand the purpose of a policy, they also actively look for ways to promote it. The ultimate goal is normative integration, meaning that the policy and corresponding implementation is the expected behavior, all others being deviant.

Throughout the text, we build on these fundamental concepts. In Chapter 2, you learn the discrete components of a policy and companion documents, as well as the technique of plain writing.

Test Your Skills

Multiple Choice Questions

1. Which of the following items are defined by policies?

A. Rules

B. Expectations

C. Patterns of behavior

D. All of the above

2. Without policy, human beings would live in a state of _______.

A. chaos

B. bliss

C. harmony

D. laziness

3. A guiding principle is best described as which of the following?

A. A financial target

B. A fundamental philosophy or belief

C. A regulatory requirement

D. A person in charge

4. Which of the following best describes corporate culture?

A. Shared attitudes, values, and goals

B. Multiculturalism

C. A requirement to all act the same

D. A religion

5. The responsibilities associated with the policy life cycle process are distributed throughout an organization. During the “develop” phase of the cybersecurity policy life cycle, the board of directors and/or executive management are responsible for which of the following?

A. Communicating guiding principles and authorizing the policy

B. Separating religion from policy

C. Monitoring and evaluating any policies

D. Auditing the policy

6. Which of the following best describes the role of policy?

A. To codify guiding principles

B. To shape behavior

C. To serve as a roadmap

D. All of the above

7. A cybersecurity policy is a directive that defines which of the following?

A. How employees should do their jobs

B. How to pass an annual audit

C. How an organization protects information assets and systems against cyber attacks and nonmalicious incidents

D. How much security insurance a company should have

8. Which of the following is not an example of an information asset?

A. Customer financial records

B. Marketing plan

C. Patient medical history

D. Building graffiti

9. What are the seven characteristics of a successful policy?

A. Endorsed, relevant, realistic, cost-effective, adaptable, enforceable, inclusive

B. Endorsed, relevant, realistic, attainable, adaptable, enforceable, inclusive

C. Endorsed, relevant, realistic, technical, adaptable, enforceable, inclusive

D. Endorsed, relevant, realistic, legal, adaptable, enforceable, inclusive

10. A policy that has been endorsed has the support of which of the following?

A. Customers

B. Creditors

C. The union

D. Management

11. Who should always be exempt from policy requirements?

A. Employees

B. Executives

C. No one

D. Salespeople

12. “Attainable” means that the policy ___________.

A. can be successfully implemented

B. is expensive

C. only applies to suppliers

D. must be modified annually

13. Which of the following statements is always true?

A. Policies stifle innovation.

B. Policies make innovation more expensive.

C. Policies should be adaptable.

D. Effective policies never change.

14. If a cybersecurity policy is violated and there is no consequence, the policy is considered to be which of the following?

A. Meaningless

B. Inclusive

C. Legal

D. Expired

15. Who must approve the retirement of a policy?

A. A compliance officer

B. An auditor

C. Executive management or the board of directors

D. Legal counsel

16. Which of the following sectors is not considered part of the “critical infrastructure”?

A. Public health

B. Commerce

C. Banking

D. Museums and arts

17. Which term best describes government intervention with the purpose of causing a specific set of actions?

A. Deregulation

B. Politics

C. Regulation

D. Amendments

18. The objectives of GLBA and HIPAA, respectively, are to protect __________.

A. financial and medical records

B. financial and credit card records

C. medical and student records

D. judicial and medical records

19. Which of the following states was the first to enact consumer breach notification?

A. Kentucky

B. Colorado

C. Connecticut

D. California

20. Which of the following terms best describes the process of developing, publishing, adopting, and reviewing a policy?

A. Policy two-step

B. Policy aging

C. Policy retirement

D. Policy life cycle

21. Who should be involved in the process of developing cybersecurity policies?

A. Only upper-management-level executives

B. Only part-time employees

C. Personnel throughout the company

D. Only outside, third-party consultants

22. Which of the following does not happen in the policy development phase?

A. Planning

B. Enforcement

C. Authorization

D. Approval

23. Which of the following occurs in the policy publication phase?

A. Communication

B. Policy dissemination

C. Education

D. All of the above

24. How often should policies be reviewed?

A. Never

B. Only when there is a significant change

C. Annually

D. At least annually, or sooner if there is a significant change

25. Normative integration is the goal of the adoption phase. This means ________.

A. There are no exceptions to the policy

B. The policy passes the stress test

C. The policy becomes expected behavior, all others being deviant

D. The policy costs little to implement

Exercises

Exercise 1.1: Understanding Guiding Principles

Reread the section “Guiding Principles” in this chapter to understand why guiding principles are crucial for any organization. Guiding principles describe the organization’s beliefs and philosophy pertaining to quality assurance and performance improvement.

Research online for different examples of public references to organizational guiding principles and compare them. Describe the similarities and differences among them.

Exercise 1.2: Identifying Corporate Culture

Identify a shared attitude, value, goal, or practice that characterizes the culture of your school or workplace.

Describe how you first became aware of the campus or workplace culture.

Exercise 1.3: Understanding the Impact of Policy

Either at school or workplace, identify a policy that in some way affects you. For example, examine a grading policy or an attendance policy.

Describe how the policy benefits (or hurts) you.

Describe how the policy is enforced.

Exercise 1.4: Understanding Critical Infrastructure

Explain what is meant by “critical infrastructure.”

What concept was introduced in Presidential Executive Order on Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure, and why is this important?

Research online and describe how the United States’ definition of “critical infrastructure” compares to what other countries consider their critical infrastructure. Include any references.

Exercise 1.5: Understanding Cyber Threats

What is the difference between cybercrime, cyber-espionage, and cyber-warfare?

What are the similarities?

Are cyber threats escalating or diminishing?

Projects

Project 1.1: Honoring the Public Trust

Banks and credit unions are entrusted with personal financial information. By visiting financial institution websites, find an example of a policy or practice that relates to protecting customer information or privacy.

Hospitals are entrusted with personal health information. By visiting hospital websites, find an example of a policy or practice that relates to protecting patient information or privacy.

In what ways are the policies or practices of banks similar to those of hospitals? How are they different?

Do either the bank policies or the hospital policies reference applicable regulatory requirements (for example, GLBA or HIPAA)?

Project 1.2: Understanding Government Regulations

The United States Affordable Care Act requires all citizens and lawful residents to have health insurance or pay a penalty. This requirement is a government policy.

A policy should be endorsed, relevant, realistic, attainable, adaptable, enforceable, and inclusive. Choose four of these characteristics and apply it to the health insurance requirement. Explain whether the policy meets the criteria.

Policies must be championed. Find an example of a person or group who championed this requirement. Explain how they communicated their support.

Project 1.3: Developing Communication and Training Skills

You have been tasked with introducing a new security policy to your campus. The new policy requires that all students and employees wear identification badges with their name and picture and that guests be given visitor badges.

Explain why an institution would adopt this type of policy.

Develop a strategy to communicate this policy campuswide.

Design a five-minute training session introducing the new policy. Your session must include participant contribution and a five-question, post-session quiz to determine whether the training was effective.

Case Study

The Tale of Two Credit Unions

Best Credit Union members really love doing business with the credit union. The staff is friendly, the service is top-notch, and the entire team is always pitching in to help the community. The credit union’s commitment to honoring the public trust is evident in its dedication to security best practices. New employees are introduced to the cybersecurity policy during orientation. Everyone participates in annual information security training.

The credit union across town, OK Credit Union, doesn’t have the same reputation. When you walk in the branch, it is sometimes hard to get a teller’s attention. Calling is not much better, because you may find yourself on hold for a long time. Even worse, it is not unusual to overhear an OK Credit Union employee talking about a member in public. OK Credit Union does not have a cybersecurity policy. It has never conducted any information security or privacy training.

Best Credit Union wants to expand its presence in the community, so it acquires OK Credit Union. Each institution will operate under its own name. The management team at Best Credit Union will manage both institutions.

You are the Information Security Officer at Best Credit Union. You are responsible for managing the process of developing, publishing, and adopting a cybersecurity policy specifically for OK Credit Union. The CEO has asked you to write up an action plan and present it at the upcoming management meeting.

Your action plan should include the following:

What you see as the biggest obstacle or challenge to accomplishing this task.

Which other personnel at Best Credit Union should be involved in this project and why.

Who at OK Credit Union should be invited to participate in the process and why.

How you are going to build support for the process and ultimately for the policy.

What happens if OK Credit Union employees start grumbling about “change.”

What happens if OK Credit Union employees do not or will not comply with the new information security policy.

References

1. “What Is Critical Infrastructure?” official website of the Department of Homeland Security, accessed 04/2018, https://www.dhs.gov/what-critical-infrastructure.

2. “Bangladesh Building Collapse Death Toll over 800,” BBC News Asia, accessed 04/2018, www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-22450419.

3. “Cyber,” Merriam-Webster Online, accessed 04/2018, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cyber.