Chapter 2

Cybersecurity Policy Organization, Format, and Styles

Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

Explain the differences between a policy, a standard, a procedure, a guideline, and a plan.

Know how to use “plain language when creating and updating your cybersecurity policy.”

Identify the different policy elements.

Include the proper information in each element of a policy.

In Chapter 1, “Understanding Cybersecurity Policy and Governance,” you learned that policies have played a significant role in helping us form and sustain our social, governmental, and corporate organizations. In this chapter, we begin by examining the hierarchy and purpose of guiding principles, policy, standards, procedures, and guidelines, as well as adjunct plans and programs. Returning to our focus on policies, we examine the standard components and composition of a policy document. You will learn that even a well-constructed policy is useless if it doesn’t deliver the intended message. The end result of complex, ambiguous, or bloated policy is, at best, noncompliance. At worst, it leads to negative consequences, because such policies may not be followed or understood. In this chapter, you will be introduced to “plain language,” which means using the simplest, most straightforward way to express an idea. Plain-language documents are easy to read, understand, and act on. By the end of the chapter, you will have the skills to construct policy and companion documents. This chapter focuses on cybersecurity policies in the private sector and not policies created by governments of any country or state.

Policy Hierarchy

As you learned in Chapter 1, a policy is a mandatory governance statement that presents management’s position. A well-written policy clearly defines guiding principles, provides guidance to those who must make present and future decisions, and serves as an implementation roadmap. Policies are important, but alone they are limited in what they can accomplish. Policies need supporting documents to give them context and meaningful application. Standards, baselines, guidelines, and procedures each play a significant role in ensuring implementation of the governance objective. The relationship between the documents is known as the policy hierarchy. In a hierarchy, with the exception of the topmost object, each object is subordinate to the one above it. In a policy hierarchy, the topmost objective is the guiding principles, as illustrated in Figure 2-1.

FIGURE 2-1 Policy Hierarchy

Cybersecurity policies should reflect the guiding principles and organizational objectives. This is why it is very important to communicate clear and well-understood organizational objectives within an organization. Standards are a set of rules and mandatory actions that provide support to a policy. Guidelines, procedures, and baselines provide support to standards. Let’s take a closer look at each of these concepts.

Standards

Standards serve as specifications for the implementation of policy and dictate mandatory requirements. For example, our password policy might state the following:

All users must have a unique user ID and password that conforms to the company password standard.

Users must not share their password with anyone regardless of title or position.

If a password is suspected to be compromised, it must be reported immediately to the help desk, and a new password must be requested.

The password standard would then dictate the required password characteristics, such as the following:

Minimum of eight upper- and lowercase alphanumeric characters

Must include at least one special character (such as *, &, $, #, !, or @)

Must not include the user’s name, the company name, or office location

Must not include repeating characters (for example, 111)

Another example of a standard is a common configuration of infrastructure devices such as routers and switches. Organizations may have dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of routers and switches, and they may have a “standard” way of configuring authentication, authorization, and accounting (AAA) for administrative sessions. They may use TACACS+ or RADIUS as the authentication standard mechanism for all routers and switches within the organization.

As you can see, the policy represents expectations that are not necessarily subject to changes in technology, processes, or management. The standard, however, is very specific to the infrastructure.

Standards are determined by management, and unlike policies, they are not subject to Board of Directors authorization. Standards can be changed by management as long as they conform to the intent of the policy. A difficult task of writing a successful standard for a cybersecurity program is achieving consensus by all stakeholders and teams within an organization. Additionally, a standard does not have to address everything that is defined in a policy. Standards should be compulsory and must be enforced to be effective.

Baselines

Baselines are the application of a standard to a specific category or grouping. Examples of groups include platform (the operating system and its version), device type (laptops, servers, desktops, routers, switches, firewalls, mobile devices, and so on), ownership (employee-owned or corporate-owned), and location (onsite, remote workers, and so on).

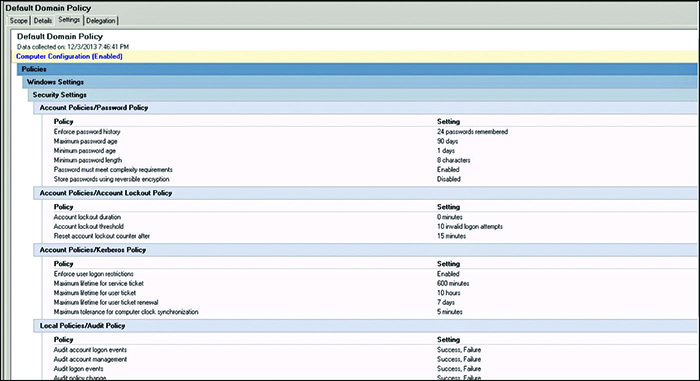

The primary objective of a baseline is uniformity and consistency. An example of a baseline related to our password policy and standard example is the mandate that a specific Active Directory Group Policy configuration (the standard) be used on all Windows devices (the group) to technically enforce security requirements, as illustrated in Figure 2-2.

FIGURE 2-2 Windows Group Policy Settings

In this example, by applying the same Active Directory Group Policy to all Windows workstations and servers, the baseline was implemented throughout the organization. In this case, there is also assurance that new devices will be configured accordingly.

Figure 2-3 shows another example of how different baselines can be enforced in the infrastructure with more sophisticated systems, such as the Cisco Identity Service Engine (ISE). Network Access Control (NAC) is a multipart solution that validates the security posture of an endpoint system before entering the network. With NAC, you can also define what resources the endpoint has access to, based on the results of its security posture. The main goal of any NAC solution is to improve the capability of the network to identify, prevent, and adapt to threats. The Cisco ISE shown in Figure 2-3 centralizes network access control based on business role and security policy to provide a consistent network access policy for end users, whether they connect through wired, wireless, or VPN. All this can be done from a centralized ISE console that then distributes enforcement across the entire network and security infrastructure.

FIGURE 2-3 Cisco ISE Dashboard

In Figure 2-3, three different endpoint systems were denied or rejected access to the network because they didn’t comply with a corporate baseline.

Guidelines

Guidelines are best thought of as teaching tools. The objective of a guideline is to help people conform to a standard. In addition to using softer language than standards, guidelines are customized for the intended audience and are not mandatory. Guidelines are akin to suggestions or advice. A guideline related to the password standard in the previous example might read like this:

“A good way to create a strong password is to think of a phrase, song title, or other group of words that is easy to remember and then convert it, like this:

“The phrase ‘Up and at ‘em at 7!’ can be converted into a strong password such as up&atm@7!.

“You can create many passwords from this one phrase by changing the number, moving the symbols, or changing the punctuation mark.”

This guideline is intended to help readers create easy-to-remember, yet strong passwords.

Guidelines are recommendations and advice to users when certain standards do not apply to your environment. Guidelines are designed to streamline certain processes according to best practices and must be consistent with the cybersecurity policies. On the other hand, guidelines often are open to interpretation and do not need to be followed to the letter.

Procedures

Procedures are instructions for how a policy, a standard, a baseline, and guidelines are carried out in a given situation. Procedures focus on actions or steps, with specific starting and ending points. There are four commonly used procedure formats:

Simple Step: Lists sequential actions. There is no decision making.

Hierarchical: Includes both generalized instructions for experienced users and detailed instructions for novices.

Graphic: This format uses either pictures or symbols to illustrate the step.

Flowchart: Used when a decision-making process is associated with the task. Flowcharts are useful when multiple parties are involved in separate tasks.

In keeping with our previous password example, the following is a Simple Step procedure for changing a user’s Windows password (Windows 7 and earlier):

Press and hold the Ctrl+Alt+Delete keys.

Click the Change Password option.

Type your current password in the top box.

Type your new password in both the second and third boxes. (If the passwords don’t match, you will be prompted to reenter your new password.)

Click OK, and then log in with your new password.

The following is the procedure to change your Windows password (Windows 10 and later):

Click Start.

Click your user account on the top, and select Change Account Settings.

Select Sign-in Options on the left panel.

Click the Change button under Password.

Enter your current password, and hit Next.

Type your new password and reenter it. Enter a password hint that will help you in case you forget your password.

Note

As with guidelines, it is important to know both your audience and the complexity of the task when designing procedures. In Chapter 8, “Communications and Operations Security,” we discuss in detail the use of cybersecurity playbooks and standard operating procedures (SOPs).

Procedures should be well documented and easy to follow to ensure consistency and adherence to policies, standards, and baselines. Like policies and standards, they should be well reviewed to ensure that they accomplish the objective of the policy and that they are accurate and still relevant.

Plans and Programs

The function of a plan is to provide strategic and tactical instructions and guidance on how to execute an initiative or how to respond to a situation, within a certain time frame, usually with defined stages and with designated resources. Plans are sometimes referred to as programs. For our purposes, the terms are interchangeable. Here are some examples of information security–related plans we discuss in this book:

Vendor Management Plan

Incident Response Plan

Business Continuity Plan

Disaster Recovery Plan

Policies and plans are closely related. For example, an Incident Response Policy will generally include the requirement to publish, maintain, and test an Incident Response Plan. Conversely, the Incident Response Plan gets its authority from the policy. Quite often, the policy will be included in the plan document.

In Practice

Policy Hierarchy Review

Let’s look at an example of how standards, guidelines, and procedures support a policy statement:

The policy requires that all media should be encrypted.

The standard specifies the type of encryption that must be used.

The guideline might illustrate how to identify removable media.

The procedure would provide the instructions for encrypting the media.

Writing Style and Technique

Style is critical. The first impression of a document is based on its style and organization. If the reader is immediately intimidated, the contents become irrelevant. Keep in mind that the role of policy is to guide behavior. That can happen only if the policy is clear and easy to use. How the document flows and the words you use will make all the difference as to how the policy is interpreted. Know your intended reader and write in a way that is understandable. Use terminology that is relevant. Most important, keep it simple. Policies that are overly complex tend to be misinterpreted. Policies should be written using plain language.

Using Plain Language

The term plain language means using the simplest, most straightforward way to express an idea.

No single technique defines plain language. Rather, plain language is defined by results—it is easy to read, understand, and use. Studies have proven that documents created using plain-language techniques are effective in a number of ways:1

Readers understand documents better.

Readers prefer plain language.

Readers locate information faster.

Documents are easier to update.

It is easier to train people.

Plain language saves time and money.

Even confident readers appreciate plain language. It enables them to read more quickly and with increased comprehension. The use of plain language is spreading in many areas of American culture, including governments at all levels, especially the federal government, health care, the sciences, and the legal system.

FYI: Warren Buffet on Using Plain Language

The following is excerpted from the preface to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s A Plain English Handbook:

“For more than forty years, I’ve studied the documents that public companies file. Too often, I’ve been unable to decipher just what is being said or, worse yet, had to conclude that nothing was being said.

“Perhaps the most common problem, however, is that a well-intentioned and informed writer simply fails to get the message across to an intelligent, interested reader. In that case, stilted jargon and complex constructions are usually the villains.

“One unoriginal but useful tip: Write with a specific person in mind. When writing Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report, I pretend that I’m talking to my sisters. I have no trouble picturing them: Though highly intelligent, they are not experts in accounting or finance. They will understand plain English, but jargon may puzzle them. My goal is simply to give them the information I would wish them to supply me if our positions were reversed. To succeed, I don’t need to be Shakespeare; I must, though, have a sincere desire to inform.

“No siblings to write to? Borrow mine: Just begin with ‘Dear Doris and Bertie.’”

Source: Securities and Exchange Commission, “A Plain English Handbook: How to Create Clear SEC Disclosure Documents,” www.sec.gov/news/extra/handbook.htm.

The Plain Language Movement

It seems obvious that everyone would want to use plain language, but as it turns out, that is not the case. There is an enduring myth that to appear official or important, documents should be verbose. The result has been a plethora of complex and confusing regulations, contracts, and, yes, policies. In response to public frustration, the Plain Language Movement began in earnest in the early 1970s.

In 1971, the National Council of Teachers of English in the United States formed the Public Doublespeak Committee. In 1972, U.S. President Richard Nixon created plain language momentum when he decreed that the “Federal Register be written in ‘layman’s terms.’” The next major event in the U.S. history of plain language occurred in 1978, when U.S. President Jimmy Carter issued Executive Orders 12,044 and 12,174. The intent was to make government regulations cost-effective and easy to understand. In 1981, U.S. President Ronald Reagan rescinded Carter’s executive orders. Nevertheless, many continued their efforts to simplify documents; by 1991, eight states had passed statutes related to plain language.

In 1998, then-President Clinton issued a Presidential Memorandum requiring government agencies to use plain language in communications with the public. All subsequent administrations have supported this memorandum. In 2010, plain-language advocates achieved a major victory when the Plain Writing Act was passed. This law requires federal government agencies to write publications and forms in a “clear, concise, well-organized” manner using plain language guidelines.

We can take a cue from the government and apply these same techniques when writing policies, standards, guidelines, and plans. The easier a policy is to understand, the better the chance of compliance.

FYI: Plain Language Results

Here’s an example of using plain language that involves the Pacific Offshore Cetacean Take Reduction Plan: Section 229.31. Not only did the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) improve the language of this regulation, it turned the critical points into a user-friendly quick reference card, made it bright yellow so it’s easy to find, and laminated it to stand up to wet conditions.

Before

After notification of NMFS, this final rule requires all CA/OR DGN vessel operators to have attended one Skipper Education Workshop after all workshops have been convened by NMFS in September 1997. CA/OR DGN vessel operators are required to attend Skipper Education Workshops at annual intervals thereafter, unless that requirement is waived by NMFS. NMFS will provide sufficient advance notice to vessel operators by mail prior to convening workshops.

After

After notification from NMFS, vessel operators must attend a skipper education workshop before commencing fishing each fishing season.

Source: www.plainlanguage.gov/examples/before_after/regfisheries.cfm

Plain Language Techniques for Policy Writing

The Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN) describes itself on its website (http://plainlanguage.gov) as a group of federal employees from many agencies and specialties, who support the use of clear communication in government writing. In March of 2011, PLAIN published the Federal Plain Language Guidelines. Some of the guidelines are specific to government publications. Many are applicable to both government and industry. The ten guidelines, listed here, are pertinent to writing policies and companion documents:

Write for your audience. Use language your audience knows and is familiar with.

Write short sentences. Express only one idea in each sentence.

Limit a paragraph to one subject. Aim for no more than seven lines.

Be concise. Leave out unnecessary words. Instead of “for the purpose of,” use “to.” Instead of “due to the fact that,” use “because.”

Don’t use jargon or technical terms when everyday words have the same meaning.

Use active voice. A sentence written in the active voice shows the subject acting in standard English sentence order: subject–verb–object. Active voice makes it clear who is supposed to do what. It eliminates ambiguity about responsibilities. Not “it must be done” but “you must do it.”

Use “must,” not “shall,” to indicate requirements. “Shall” is imprecise. It can indicate either an obligation or a prediction. The word “must” is the clearest way to convey to your audience that they have to do something.

Use words and terms consistently throughout your documents. If you use the term “senior citizens” to refer to a group, continue to use this term throughout your document. Don’t substitute another term, such as “the elderly” or “the aged.” Using a different term may cause the reader to wonder if you are referring to the same group.

Omit redundant pairs or modifiers. For example, instead of “cease and desist,” use either “cease” or “desist.” Even better, use a simpler word such as “stop.” Instead of saying “the end result was the honest truth,” say “the result was the truth.”

Avoid double negatives and exceptions to exceptions. Many ordinary terms have a negative meaning, such as unless, fail to, notwithstanding, except, other than, unlawful (“un-” words), disallowed (“dis-” words), terminate, void, insufficient, and so on. Watch out for them when they appear after “not.” Find a positive word to express your meaning.

Want to learn more about using plain language? The official website of PLAIN has a wealth of resources, including the Federal Plain Language Guidelines, training materials and presentations, videos, posters, and references.

In Practice

Understanding Active and Passive Voice

Here are some key points to keep in mind concerning active and passive voice:

Voice refers to the relationship of a subject and its verb.

Active voice refers to a verb that shows the subject acting.

Passive voice refers to a verb that shows the subject being acted upon.

Active Voice

A sentence written in the active voice shows the subject acting in standard English sentence order: subject–verb–object. The subject names the agent responsible for the action, and the verb identifies the action the agent has set in motion. Example: “George threw the ball.”

Passive Voice

A sentence written in the passive voice reverses the standard sentence order. Example: “The ball was thrown by George.” George, the agent, is no longer the subject but now becomes the object of the preposition “by.” The ball is no longer the object but now becomes the subject of the sentence, where the agent preferably should be.

Conversion Steps

To convert a passive sentence into an active one, take these steps:

Identify the agent.

Move the agent to the subject position.

Remove the helping verb (to be).

Remove the past participle.

Replace the helping verb and participle with an action verb.

Examples of Conversion

Original: The report has been completed.

Revised: Stefan completed the report.

Original: A decision will be made.

Revised: Omar will decide.

In Practice

U.S. Army Clarity Index

The Clarity Index was developed to encourage plain writing. The index has two factors: average number of words per sentence and percentage of words longer than three syllables. The index adds together the two factors. The target is an average of 15 words per sentence and with 15% of the total text composed of three syllables or less. A resulting index between 20 and 40 is ideal and indicates the right balance of words and sentence length. In the following example (excerpted from Warren Buffet’s SEC introduction), the index is composed of an average of 18.5 words per sentence, and 11.5% of the words are three syllables or less. An index of 30 falls squarely in the ideal range!

Sentence |

Number of Words per Sentence |

Number and Percentage of Words with Three or More Syllables |

|---|---|---|

For more than forty years, I’ve studied the documents that public companies file. |

13 |

Two words: 2/13 = 15% |

Too often, I’ve been unable to decipher just what is being said or, worse yet, had to conclude that nothing was being said. |

23 |

One word: 1/23 = 4% |

Perhaps the most common problem, however, is that a well-intentioned and informed writer simply fails to get the message across to an intelligent, interested reader. |

26 |

Three words: 3/26= 11% |

In that case, stilted jargon and complex constructions are usually the villains. |

12 |

One word 2/12= 16% |

Total |

74 |

46% |

Average |

18.5 |

11.5% |

Clarity Index |

18.5 + 11.5 = 30 |

|

Policy Format

Writing policy documents can be challenging. Policies are complex documents that must be written to withstand legal and regulatory scrutiny and at the same time be easily read and understood by the reader. The starting point for choosing a format is identifying the policy audience.

Understand Your Audience

Who the policy is intended for is referred to as the policy audience. It is imperative, during the planning portion of the security policy project, to clearly define the audience. Policies may be intended for a particular group of employees based on job function or role. For example, an application development policy is targeted to developers. Other policies may be intended for a particular group or individual based on organizational role, such as a policy defining the responsibility of the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO). The policy, or portions of it, can sometimes apply to people outside of the company, such as business partners, service providers, contractors, or consultants. The policy audience is a potential resource during the entire policy life cycle. Indeed, who better to help create and maintain an effective policy than the very people whose job it is to use those policies in the context of their everyday work?

Policy Format Types

Organize, before you begin writing! It is important to decide how many sections and subsections you will require before you put pen to paper. Designing a template that allows the flexibility of editing will save considerable time and reduce aggravation. In this section you will learn the different policy sections and subsections, as well as the policy document formation options.

There are two general ways to structure and format your policy:

Singular policy: You write each policy as a discrete document.

Consolidated policy: Grouping similar and related policies together.

Consolidated policies are often organized by section and subsection.

Table 2-1 illustrates policy document format options.

TABLE 2-1 Policy Document Format Options

Description |

Example |

|---|---|

Singular policy |

Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) Policy: Specific to the role and responsibility of the Information Security Officer. |

Consolidated policy section |

Governance Policy: Addresses the role and responsibilities of the Board of Directors, executive management, Chief Risk Officer, CISO, Compliance Officer, legal counsel, auditor, IT Director, and users. |

The advantage to individual policies is that each policy document can be short, clean, and crisp, and targeted to its intended audience. The disadvantage is the need to manage multiple policy documents and the chance that they will become fragmented and lose consistency. The advantage to consolidation is that it presents a composite management statement in a single voice. The disadvantage is the potential size of the document and the reader challenge of locating applicable sections.

In the first edition of this book, we limited our study to singular documents. Since then, both the use of technology and the regulatory landscape have increased exponentially—only outpaced by escalating threats. In response to this ever-changing environment, the need for and number of policies has grown. For many organizations, managing singular policies has become unwieldy. The current trend is toward consolidation. Throughout this edition, we are going to be consolidating policies by security domain.

Regardless of which format you choose, do not include standards, baselines, guidelines, or procedures in your policy document. If you do so, you will end up with one big unruly document. And you will undoubtedly encounter one or more of the following problems:

Management challenge: Who is responsible for managing and maintaining a document that has multiple contributors?

Difficulty of updating: Because standards, guidelines, and procedures change far more often than policies, updating this whale of a document will be far more difficult than if these elements were properly treated separately. Version control will become a nightmare.

Cumbersome approval process: Various regulations as well as the Corporate Operating Agreement require that the Board of Directors approve new policies as well as changes. Mashing it all together means that every change to a procedure, guideline, or standard will potentially require the Board to review and approve. This will become very costly and cumbersome for everyone involved.

Policy Components

Policy documents have multiple sections or components (see Table 2-2). How the components are used and in what order will depend on which format—singular or consolidated—you choose. In this section, we examine the composition of each component. Consolidated policy examples are provided in the “In Practice” sidebars.

TABLE 2-2 Policy Document Components

Component |

Purpose |

|---|---|

Version control |

To track changes |

Introduction |

To frame the document |

Policy heading |

To identify the topic |

Policy goals and objectives |

To convey intent |

Policy statement |

Mandatory directive |

Policy exceptions |

To acknowledge exclusions |

Policy enforcement clause |

Violation sanctions |

Administrative notations |

Additional information |

Policy definitions |

Glossary of terms |

Version Control

Best practices dictate that policies are reviewed annually to ensure they are still applicable and accurate. Of course, policies can (and should) be updated whenever there is a relevant change driver. Version control, as it relates to policies, is the management of changes to the document. Versions are usually identified by a number or letter code. Major revisions generally advance to the next letter or digit (for example, from 2.0 to 3.0). Minor revisions generally advance as a subsection (for example, from 2.0 to 2.1). Version control documentation should include the change date, name of the person or persons making the change, a brief synopsis of the change, the name of the person, committee, or board that authorized the change, and the effective date of the change.

For singular policy documents, this information is split between the policy heading and the administrative notation sections.

For consolidated policy documents, a version control table is included either at the beginning of the document or at the beginning of a section.

In Practice

Version Control Table

Version control tables are used in consolidated policy documents. The table is located after the title page, before the table of contents. Version control provides the reader with a history of the document. Here’s an example:

V. |

Editor |

Purpose |

Change Description |

Authorized By |

Effective Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1.0 |

S. Ford, EVP |

|

Original. |

Sr. management committee |

01/17/18 |

1.1 |

S. Ford, EVP |

Subsection addition |

2.5: Disclosures to Third Parties. |

Sr. management committee |

03/07/18 |

1.2 |

S. Ford, EVP |

Subsection update |

4.4: Border Device Management. 5.8: Wireless Networks. |

Sr. management committee |

01/14/19 |

-- |

S. Ford, EVP |

Annual review |

No change. |

Sr. management committee |

01/18/19 |

2.0 |

B. Lin, CIO |

Section revision |

Revised “Section 1.0: Governance and Risk Management” to reflect internal reorganization of roles and responsibilities. |

Acme, Board of Directors |

05/13/19 |

Introduction

Think of the introduction as the opening act. This is where we first meet the readers and have the opportunity to engage them. Here are the objectives of the introduction:

To provide context and meaning

To convey the importance of understanding and adhering to the policy

To acquaint the reader with the document and its contents

To explain the exemption process as well as the consequence of noncompliance

To reinforce the authority of the policy

The first part of the introduction should make the case for why policies are necessary. It is a reflection of the guiding principles, defining for the reader the core values the company believes in and is committed to. This is also the place to set forth the regulatory and contractual obligations that the company has—often by listing which regulations, such as GLBA, HIPAA, or MA CMR 17 201, pertain to the organization as well as the scope of the policy.

The second part of the introduction should leave no doubt that compliance is mandatory. A strong statement of expectation from a senior authority, such as the Chairman of the Board, CEO, or President, is appropriate. Users should understand that they are unequivocally and directly responsible for following the policy in the course of their normal employment or relationship with the company. It should also make clear that questions are welcome and a resource is available who can clarify the policy and/or assist with compliance.

The third part of the introduction should describe the policy document, including the structure, categories, and storage location (for example, the company intranet). It should also reference companion documents such as standards, guidelines, programs, and plans. In some cases, the introduction includes a revision history, the stakeholders that may have reviewed the policy, and who to contact to make any modifications.

The fourth part of the introduction should explain how to handle situations where compliance may not be feasible. It should provide a high-level view of the exemption and enforcement process. The section should also address the consequences of willful noncompliance.

For singular policy documents, the introduction should be a separate document.

For consolidated policy documents, the introduction serves as the preface and follows the version control table.

In Practice

Introduction

The introduction has five objectives: to provide context and meaning, to convey the importance of understanding and adhering to the policy, to acquaint the reader with the document, to explain the exemption process and the consequence of noncompliance, and, last, to thank the reader and reinforce the authority of the policy. Each objective is called out in the following example:

[Objective 1: Provide context and meaning]

The 21st century environment of connected technologies offers us many exciting present and future opportunities. Unfortunately, there are those who seek to exploit these opportunities for personal, financial, or political gain. We, as an organization, are committed to protecting our clients, employees, stakeholders, business partners, and community from harm and to providing exceptional service.

The objective of our Cybersecurity Policy is to protect and respect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of client information, company proprietary data, and employee data, as well as the infrastructure that supports our services and business activities.

This policy has been designed to meet or exceed applicable federal and state information security–related regulations, including but not limited to sections 501 and 505(b) of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) and MA CMR 17 201 as well as our contractual obligations.

The scope of the Cybersecurity Policy extends to all functional areas and all employees, directors, consultants, contractors, temporary staff, co-op students, interns, partners and third-party employees, and joint venture partners, unless explicitly excluded.

[Objective 2: Convey the importance of understanding and adhering to the policy]

Diligent information security practices are a civic responsibility and a team effort involving the participation and support of every employee and affiliate who deals with information and/or information systems. It is the responsibility of every employee and affiliate to know, understand, and adhere to these policies, and to conduct their activities accordingly. If you have any questions or would like more information, I encourage you to contact our Compliance Officer at x334.

[Objective 3: Acquaint the reader with the document and its contents]

At first glance, the policy [or policies, if you are using singular policy documents] may appear daunting. If you take a look at the table of contents [or list, if you are using singular policy documents] you will see that the Cybersecurity Policy is organized by category. These categories form the framework of our Cybersecurity Program. Supporting the policies are implementation standards, guidelines, and procedures. You can find these documents in the Governance section of our online company library.

[Objective 4: Explain the consequence of noncompliance as well as the exception process]

Where compliance is not technically feasible or justified by business needs, an exemption may be granted. Exemption requests must be submitted in writing to the Chief Operating Officer (COO), including justification and benefits attributed to the exemption. Unless otherwise stated, the COO and the President have the authority to grant waivers.

Willful violation of this policy [or policies, if you are using singular policy documents] may result in disciplinary action, which may include termination for employees and temporaries, a termination of employment relations in the case of contractors and consultants, and dismissal for interns and volunteers. Additionally, individuals may be subject to civil and criminal prosecution.

[Objective 5: Thank the reader and provide a seal of authority]

I thank you in advance for your support, as we all do our best to create a secure environment and to fulfill our mission.

—Anthony Starks, Chief Executive Officer (CEO)

Policy Heading

A policy heading identifies the policy by name and provides the reader with an overview of the policy topic or category. The format and contents of the heading significantly depend on the format (singular or consolidated) you are using.

Singular policies must be able to stand on their own, which means it is necessary to include significant logistical detail in each heading. The information contained in a singular policy heading may include the organization or division name, category (section), subsection, policy number, name of the author, version number, approval authority, effective date of the policy, regulatory cross-reference, and a list of supporting resources and source material. The topic is generally self-explanatory and does not require an overview or explanation.

In a consolidated policy document, the heading serves as a section introduction and includes an overview. Because the version number, approval authority, and effective date of the policy have been documented in the version control table, it is unnecessary to include them in section headings. Regulatory cross-reference (if applicable), lead author, and supporting documentation are found in the Administrative Notation section of the policy.

In Practice

Policy Heading

A consolidated policy heading serves as the introduction to a section or category.

Section 1: Governance and Risk Management

Overview

Governance is the set of responsibilities and practices exercised by the Board of Directors and management team with the goal of providing strategic direction, ensuring that organizational objectives are achieved, risks are managed appropriately, and enterprise resources are used responsibly. The principal objective of an organization’s risk management process is to provide those in leadership and data steward roles with the information required to make well-informed decisions.

Policy Goals and Objectives

Policy goals and objectives act as a gateway to the content to come and the security principle they address. This component should concisely convey the intent of the policy. Note that even a singular policy can have multiple objectives. We live in a world where business matters are complex and interconnected, which means that a policy with a single objective might risk not covering all aspects of a particular situation. It is therefore important, during the planning phase, to pay appropriate attention to the different objectives the security policy should seek to achieve.

Singular policies list the goals and objectives either in the policy heading or in the body of the document.

In a consolidated policy document, the goals and objectives are grouped and follow the policy heading.

In Practice

Policy Goals and Objectives

Goals and objectives should convey the intent of the policy. Here’s an example:

Goals and Objectives for Section 1: Governance and Risk Management

To demonstrate our commitment to information security

To define organizational roles and responsibilities

To provide the framework for effective risk management and continuous assessment

To meet regulatory requirements

Policy Statement

Up to this point in the document, we have discussed everything but the actual policy statement. The policy statement is best thought of as a high-level directive or strategic roadmap. This is the section where we lay out the rules that need to be followed and, in some cases, reference the implementation instructions (standards) or corresponding plans. Policy statements are intended to provide action items as well as the framework for situational responses. Policies are mandatory. Deviations or exceptions must be subject to a rigorous examination process.

In Practice

Policy Statement

The bulk of the final policy document is composed of policy statements. Here is an example of an excerpt from a governance and risk management policy:

1.1. Roles and Responsibilities

1.1.1. The Board of Directors will provide direction for and authorize the Cybersecurity Policy and corresponding program.

1.1.2. The Chief Operating Officer (COO) is responsible for the oversight of, communication related to, and enforcement of the Cybersecurity Policy and corresponding program.

1.1.3. The COO will provide an annual report to the Board of Directors that provides them with the information necessary to measure the organizations’ adherence to the Cybersecurity Policy objectives and to gauge the changing nature of risk inherent in lines of business and operations.

1.1.4. The Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) is charged with the implementation of the Cybersecurity Policy and standards including but not limited to:

Ensuring that administrative, physical, and technical controls are selected, implemented, and maintained to identify, measure, monitor, and control risks, in accordance with applicable regulatory guidelines and industry best practices

Managing risk assessment–related remediation

Authorizing access control permissions to client and proprietary information

Reviewing access control permissions in accordance with the audit standard

Responding to security incidents

1.1.5. In-house legal counsel is responsible for communicating to all contracted entities the information security requirements that pertain to them as detailed within the Cybersecurity Policy and the Vendor Management Program.

Policy Exceptions and the Exemption Process

Realistically, there will be situations where it is not possible or practical, or perhaps may even be harmful, to obey a policy directive. This does not invalidate the purpose or quality of the policy. It just means that some special situations will call for exceptions to the rule. Policy exceptions are agreed waivers that are documented within the policy. For example, in order to protect its intellectual property, Company A has a policy that bans digital cameras from all company premises. However, a case could be made that the HR department should be equipped with a digital camera to take pictures of new employees to paste them on their ID badges. Or maybe the Security Officer should have a digital camera to document the proceedings of evidence gathering after a security breach has been detected. Both examples are valid reasons why a digital camera might be needed. In these cases, an exception to the policy could be added to the document. If no exceptions are ever to be allowed, this should be clearly stated in the Policy Statement section as well.

An exemption or waiver process is required for exceptions identified after the policy has been authorized. The exemption process should be explained in the introduction. The criteria or conditions for exemptions should not be detailed in the policy, only the method or process for requesting an exemption. If we try to list all the conditions to which exemptions apply, we risk creating a loophole in the exemption itself. It is also important that the process follow specific criteria under which exemptions are granted or rejected. Whether an exemption is granted or rejected, the requesting party should be given a written report with clear reasons either way.

Finally, it is recommended that you keep the number of approved exceptions and exemptions low, for several reasons:

Too many built-in exceptions may lead employees to perceive the policy as unimportant.

Granting too many exemptions may create the impression of favoritism.

Exceptions and exemptions can become difficult to keep track of and successfully audit.

If there are too many built-in exceptions and/or exemption requests, it may mean that the policy is not appropriate in the first place. At that point, the policy should be subject to review.

In Practice

Policy Exception

Here’s a policy exception that informs the reader who is not required to conform to a specific clause and under what circumstances and whose authorization:

“At the discretion of in-house legal counsel, contracted entities whose contracts include a confidentiality clause may be exempted from signing nondisclosure agreements.”

The process for granting post-adoption exemptions should be included in the introduction. Here’s an example:

“Where compliance is not technically feasible or as justified by business needs, an exemption may be granted. Exemption requests must be submitted in writing to the COO, including justification and benefits attributed to the exemption. Unless otherwise stated, the COO and the President have the authority to grant waivers.”

Policy Enforcement Clause

The best way to deliver the message that policies are mandatory is to include the penalty for violating the rules. The policy enforcement clause is where the sanctions for non-adherence to the policy are unequivocally stated to reinforce the seriousness of compliance. Obviously, you must be careful with the nature of the penalty. It should be proportional to the rule that was broken, whether it was accidental or intentional, and the level of risk the company incurred.

An effective method of motivating compliance is proactive training. All employees should be trained in the acceptable practices presented in the security policy. Without training, it is hard to fault employees for not knowing they were supposed to act in a certain fashion. Imposing disciplinary actions in such situations can adversely affect morale. We take a look at various training, education, and awareness tools and techniques in later chapters.

In Practice

Policy Enforcement Clause

This example of a policy enforcement clause advises the reader, in no uncertain terms, what will happen if they do not obey the rules. It belongs in the introduction and, depending on the circumstances, may be repeated within the policy document.

“Violation of this policy may result in disciplinary action, which may include termination for employees and temporaries, a termination of employment relations in the case of contractors and consultants, and dismissal for interns and volunteers. Additionally, individuals are subject to civil and criminal prosecution.”

Administrative Notations

The purpose of administrative notations is to refer the reader to additional information and/or provide a reference to an internal resource. Notations include regulatory cross-references, the name of corresponding documents such as standards, guidelines, and programs, supporting documentation such as annual reports or job descriptions, and the policy author’s name and contact information. You should include only notations that are applicable to your organization. However, you should be consistent across all policies.

Singular policies incorporate administrative notations either in the heading, at the end of the document, or split between the two locations. How this is handled depends on the policy template used by the company.

In a consolidated policy document, the administrative notations are located at the end of each section.

In Practice

Administrative Notations

Administrative notations are a reference point for additional information. If the policy is distributed in electronic format, it is a great idea to hyperlink the notations directly to the source document.

Regulatory Cross Reference

Section 505(b) of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

MA CMR 17 201

Lead Author

B. Lin, Chief Information Officer

Corresponding Documents

Risk Management Standards

Vendor Management Program

Supporting Documentation

Job descriptions as maintained by the Human Resources Department.

Policy Definitions

The Policy Definition section is a glossary of terms, abbreviations, and acronyms used in the document that the reader may be unfamiliar with. Adding definitions to the overall document will aid the target audience in understanding the policy, and will therefore make the policy a much more effective document.

The general rule is to include definitions for any instance of industry-specific, technical, legal, or regulatory language. When deciding what terms to include, it makes sense to err on the side of caution. The purpose of the security policy as a document is communication and education. The target audience for this document usually encompasses all employees of the company, and sometimes outside personnel. Even if some technical topics are well known to all in-house employees, some of those outside individuals who come in contact with the company—and therefore are governed by the security policy—may not be as well versed in the policy’s technical aspects.

Simply put, before you begin writing down definitions, it is recommended that you first define the target audience for whom the document is crafted, and cater to the lowest common denominator to ensure optimum communication efficiency.

Another reason why definitions should not be ignored is for the legal ramification they represent. An employee cannot pretend to have thought that a certain term used in the policy meant one thing when it is clearly defined in the policy itself. When you’re choosing which words will be defined, therefore, it is important not only to look at those that could clearly be unknown, but also those that should be defined to remove any and all ambiguity. A security policy could be an instrumental part of legal proceedings and should therefore be viewed as a legal document and crafted as such.

In Practice

Terms and Definitions

Any term that may not be familiar to the reader or is open to interpretation should be defined.

Here’s an example of an abbreviation:

MOU—Memorandum of Understanding

Here’s an example of a regulatory reference:

MA CMR 17 201—Standards for the Protection of Personal Information of Residents of the Commonwealth establishes minimum standards to be met in connection with the safeguarding of personal information of Massachusetts residents.

And, finally, here are a few examples of security terms:

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS): An attack in which there is a massive volume of IP packets from multiple sources. The flood of incoming packets consumes available resources resulting in the denial of service to legitimate users.

Exploit: A malicious program designed to “exploit” or take advantage of a single vulnerability or set of vulnerabilities.

Phishing: Where the attacker presents a link that looks like a valid, trusted resource to a user. When the user clicks it, he is prompted to disclose confidential information such as his username and password.

Pharming: The attacker uses this technique to direct a customer’s URL from a valid resource to a malicious one that could be made to appear as the valid site to the user. From there, an attempt is made to extract confidential information from the user.

Malvertising: The act of incorporating malicious ads on trusted websites, which results in users’ browsers being inadvertently redirected to sites hosting malware.

Logic bomb: A type of malicious code that is injected into a legitimate application. An attacker can program a logic bomb to delete itself from the disk after it performs the malicious tasks on the system. Examples of these malicious tasks include deleting or corrupting files or databases and executing a specific instruction after certain system conditions are met.

Trojan horse: A type of malware that executes instructions determined by the nature of the Trojan to delete files, steal data, or compromise the integrity of the underlying operating system. Trojan horses typically use a form of social engineering to fool victims into installing such software on their computers or mobile devices. Trojans can also act as backdoors.

Backdoor: A piece of malware or configuration change that allows attackers to control the victim’s system remotely. For example, a backdoor can open a network port on the affected system so that the attacker can connect and control the system.

Summary

You now know that policies need supporting documents to give them context and meaningful application. Standards, guidelines, and procedures provide a means to communicate specific ways to implement our policies. We create our organizational standards, which specify the requirements for each policy. We offer guidelines to help people comply with standards. We create sets of instructions known as procedures so tasks are consistently performed. The format of our procedure—Simple Step, Hierarchical, Graphic, or Flowchart—depends on the complexity of the task and the audience. In addition to our policies, we create plans or programs to provide strategic and tactical instructions and guidance on how to execute an initiative or how to respond to a situation, within a certain time frame, usually with defined stages and with designated resources.

Writing policy documents is a multistep process. First, we need to define the audience for which the document is intended. Then, we choose the format. Options are to write each policy as a discrete document (singular policy) or to group like policies together (consolidated policy). Last, we need to decide upon the structure, including the components to include and in what order.

The first and arguably most important section is the introduction. This is our opportunity to connect with the reader and to convey the meaning and importance of our policies. The introduction should be written by the “person in charge,” such as the CEO or President. This person should use the introduction to reinforce company-guiding principles and correlate them with the rules introduced in the security policy.

Specific to each policy are the heading, goals and objectives, the policy statement, and (if applicable) exceptions. The heading identifies the policy by name and provides the reader with an overview of the policy topic or category. The goals and objectives convey what the policy is intended to accomplish. The policy statement is where we lay out the rules that need to be followed and, in some cases, reference the implementation instructions (standards) or corresponding programs. Policy exceptions are agreed waivers that are documented within the policy.

An exemption or waiver process is required for exceptions identified after a policy has been authorized. The policy enforcement clause is where the sanctions for willful non-adherence to the policy are unequivocally stated to reinforce the seriousness of compliance. Administrative notations refer the reader to additional information and/or provide a reference to an internal resource. The policy definition section is a glossary of terms, abbreviations, and acronyms used in the document that the reader may be unfamiliar with.

Recognizing that the first impression of a document is based on its style and organization, we studied the work of the Plain Language Movement. Our objective for using plain language is to produce documents that are easy to read, understand, and use. We looked at ten techniques from the Federal Plain Language Guideline that we can (and should) use for writing effective policies. In the next section of the book, we put these newfound skills to use.

Test Your Skills

Multiple Choice Questions

1. The policy hierarchy is the relationships between which of the following?

A. Guiding principles, regulations, laws, and procedures

B. Guiding principles, standards, guidelines, and procedures

C. Guiding principles, instructions, guidelines, and programs

D. None of the above

2. Which of the following statements best describes the purpose of a standard?

A. To state the beliefs of an organization

B. To reflect the guiding principles

C. To dictate mandatory requirements

D. To make suggestions

3. Which of the following statements best describes the purpose of a guideline?

A. To state the beliefs of an organization

B. To reflect the guiding principles

C. To dictate mandatory requirements

D. To help people conform to a standard

4. Which of the following statements best describes the purpose of a baseline?

A. To measure compliance

B. To ensure uniformity across a similar set of devices

C. To ensure uniformity and consistency

D. To make suggestions

5. Simple Step, Hierarchical, Graphic, and Flowchart are examples of which of the following formats?

A. Policy

B. Program

C. Procedure

D. Standard

6. Which of the following terms best describes instructions and guidance on how to execute an initiative or how to respond to a situation, within a certain time frame, usually with defined stages and with designated resources?

A. Plan

B. Policy

C. Procedure

D. Package

7. Which of the following statements best describes a disadvantage to using the singular policy format?

A. The policy can be short.

B. The policy can be targeted.

C. You may end up with too many policies to maintain.

D. The policy can easily be updated.

8. Which of the following statements best describes a disadvantage to using the consolidated policy format?

A. Consistent language is used throughout the document.

B. Only one policy document must be maintained.

C. The format must include a composite management statement.

D. The potential size of the document.

9. Policies, standards, guidelines, and procedures should all be in the same document.

A. True

B. False

C. Only if the company is multinational

D. Only if the documents have the same author

10. Version control is the management of changes to a document and should include which of the following elements?

A. Version or revision number

B. Date of authorization or date that the policy took effect

C. Change description

D. All of the above

11. What is an exploit?

A. A phishing campaign

B. A malicious program or code designed to “exploit” or take advantage of a single vulnerability or set of vulnerabilities

C. A network or system weakness

D. A protocol weakness

12. The name of the policy, policy number, and overview belong in which of the following sections?

A. Introduction

B. Policy Heading

C. Policy Goals and Objectives

D. Policy Statement

13. The aim or intent of a policy is stated in the ________.

A. introduction

B. policy heading

C. policy goals and objectives

D. policy statement

14. Which of the following statements is true?

A. A security policy should include only one objective.

B. A security policy should not include any exceptions.

C. A security policy should not include a glossary.

D. A security policy should not list all step-by-step measures that need to be taken.

15. The _________ contains the rules that must be followed.

A. policy heading

B. policy statement

C. policy enforcement clause

D. policy goals and objectives

16. A policy should be considered _____.

A. mandatory

B. discretionary

C. situational

D. optional

17. Which of the following best describes policy definitions?

A. A glossary of terms, abbreviations, and acronyms used in the document that the reader may be unfamiliar with

B. A detailed list of the possible penalties associated with breaking rules set forth in the policy

C. A list of all the members of the security policy creation team

D. None of the above

18. The _________ contains the penalties that would apply if a portion of the security policy were to be ignored by an employee.

A. policy heading

B. policy statement

C. policy enforcement clause

D. policy statement of authority

19. What component of a security policy does the following phrase belong to? “Wireless networks are allowed only if they are separate and distinct from the corporate network.”

A. Introduction

B. Administrative notation

C. The policy heading

D. The policy statement

20. There may be situations where it is not possible to comply with a policy directive. Where should the exemption or waiver process be explained?

A. Introduction

B. The policy statement

C. The policy enforcement clause

D. The policy exceptions

21. The name of the person/group (for example, executive committee) that authorized the policy should be included in ___________________.

A. the version control table or the policy statement

B. the heading or the policy statement

C. the policy statement or the policy exceptions

D. the version control table or the policy heading

22. When you’re drafting a list of exceptions for a security policy, the language should _________________.

A. be as specific as possible

B. be as vague as possible

C. reference another, dedicated document

D. None of the above

23. If supporting documentation would be of use to the reader, it should be __________________.

A. included in full in the policy document

B. ignored because supporting documentation does not belong in a policy document

C. listed in either the Policy Heading or Administrative Notation section

D. included in a policy appendix

24. When writing a policy, standard, guideline, or procedure, you should use language that is ___________.

A. technical

B. clear and concise

C. legalese

D. complex

25. Readers prefer “plain language” because it __________________.

A. helps them locate pertinent information

B. helps them understand the information

C. saves time

D. All of the above

26. Which of the following is not a characteristic of plain language?

A. Short sentences

B. Using active voice

C. Technical jargon

D. Seven or fewer lines per paragraph

27. Which of the following terms is best to use when indicating a mandatory requirement?

A. must

B. shall

C. should not

D. may not

28. A company that uses the term “employees” to refer to workers who are on the company payroll should refer to them throughout their policies as _________.

A. workforce members

B. employees

C. hired hands

D. workers

29. Which of the following statements is true regarding policy definitions?

A. They should be defined and maintained in a separate document.

B. The general rule is to include definitions for any topics except technical, legal, or regulatory language.

C. The general rule of policy definitions is to include definitions for any instance of industry-specific, technical, legal, or regulatory language.

D. They should be created before any policy or standards.

30. Even the best-written policy will fail if which of the following is true?

A. The policy is too long.

B. The policy is mandated by the government.

C. The policy doesn’t have the support of management.

D. All of the above.

Exercises

Exercise 2.1: Creating Standards, Guidelines, and Procedures

The University System has a policy that states, “All students must comply with their campus attendance standard.”

You are tasked with developing a standard that documents the mandatory requirements (for example, how many classes can be missed without penalty). Include at least four requirements.

Create a guideline to help students adhere to the standard you created.

Create a procedure for requesting exemptions to the policy.

Exercise 2.2: Writing Policy Statements

Who would be the target audience for a policy related to campus elections?

Keeping in mind the target audience, compose a policy statement related to campus elections.

Compose an enforcement clause.

Exercise 2.3: Writing a Policy Introduction

Write an introduction to the policy you created in Exercise 2.2.

Generally an introduction is signed by an authority. Who would be the appropriate party to sign the introduction?

Write an exception clause.

Exercise 2.4: Writing Policy Definitions

The purpose of policy definitions is to clarify ambiguous terms. If you were writing a policy for an on-campus student audience, what criteria would you use to determine which terms should have definitions?

What are some examples of terms you would define?

Exercise 2.5: Using Clear Language

Identify the passive verb in each of the following lines. Hint: Test by inserting a subject (for example, he or we) before the verb.

a) was written

will write

has written

is writing

b) shall deliver

may deliver

is delivering

is delivered

c) has sent

were sent

will send

is sending

d) should revoke

will be revoking

has revoked

to be revoked

e) is mailing

have been mailed

having mailed

will mail

f) may be requesting

are requested

have requested

will request

Shorten the following phrases (for example, “consideration should be given to” can be shortened to “consider”).

Original

Modified

a) For the purpose of

To

b) Due to the fact that

Because

c) Forwarded under separate cover

Sent separately

Delete the redundant modifiers (for example, for “actual facts,” you would delete the word “actual”):

a) Honest truth

b) End result

c) Separate out

d) Start over again

e) Symmetrical in form

f) Narrow down

Projects

Project 2.1: Comparing Security Policy Templates

Search online for “cybersecurity policy templates.”

Read the documents and compare them.

Identify the policy components that were covered in this chapter.

Search now for a real-world policy, such as Tuft’s University Two-factor Authentication Policy at https://it.tufts.edu/univ-pol.

Choose a couple terms in the policy that are not defined in the Policy Definitions section and write a definition for each.

Project 2.2: Analyzing the Enterprise Security Policy for the State of New York

Search online for the “State of New York Cybersecurity Policy P03-002” document.

Read the policy. What is your overall opinion of the policy?

What is the purpose of the italic format? In your opinion, is it useful or distracting?

The policy references standards and procedures. Identify at least one instance of each. Can you find any examples of where a standard, guideline, or procedure is embedded in the policy document?

Project 2.3: Testing the Clarity of a Policy Document

Locate your school’s cybersecurity policy. (It may have a different name.)

Select a section of the policy and use the U.S. Army’s Clarity Index to evaluate the ease of reading (reference the “In Practice: U.S. Army Clarity Index” sidebar for instructions).

Explain how you would make the policy more readable.

Case Study

Clean Up the Library Lobby

The library includes the following exhibition policy:

“Requests to utilize the entrance area at the library for the purpose of displaying posters and leaflets gives rise to the question of the origin, source, and validity of the material to be displayed. Posters, leaflets, and other display materials issued by the Office of Campus Security, Office of Student Life, the Health Center, and other authoritative bodies are usually displayed in libraries, but items of a fractious or controversial kind, while not necessarily excluded, are considered individually.”

The lobby of the school library is a mess. Plastered on the walls are notes, posters, and cards of all sizes and shapes. It is impossible to tell current from outdated messages. It is obvious that no one is paying any attention to the library exhibition policy. You have been asked to evaluate the policy and make the necessary changes needed to achieve compliance.

Consider your audience. Rewrite the policy using plain language guidelines. You may encounter resistance to modifying the policy, so document the reason for each change, such as changing passive voice to active voice, eliminating redundant modifiers, and shortening sentences.

Expand the policy document to include goals and objectives, exceptions, and a policy enforcement clause.

Propose standards and guidelines to support the policy.

Propose how you would suggest introducing the policy, standards, and guidelines to the campus community.

References

1. Baldwin, C. Plain Language and the Document Revolution. Washington, D.C.: Lamplighter, 1999.

Regulations and Directives Cited

Carter, J. “Executive Order—Improving Government Regulations,” accessed 05/2018, www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=30539.

Clinton, W. “President Clinton’s Memorandum on Plain Language in Government Writing,” accessed 05/2018, www.plainlanguage.gov/whatisPL/govmandates/memo.cfm.

Obama, B. “Executive Order 13563—Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review,” accessed 05/2018, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/01/18/executive-order-13563-improving-regulation-and-regulatory-review.

“Plain Writing Act of 2010” PUBLIC LAW 111–274, Oct. 13, 2010, accessed 05/2018, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ274/pdf/PLAW-111publ274.pdf.

Other References

Krause, Micki, CISSP, and Harold F. Tipton, CISSP. 2004. Information Security Management Handbook, Fifth Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Auerbach Publications.