CHAPTER 3

CREATIVE DISRUPTION IN THE ANTI ORGANIZATION AGE

A creative economy is the fuel of magnificence.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

“HEY, SO YOU want to find an apartment together?”

I was speaking into the old gray telephone handset with big orange buttons that hung from my parents’ kitchen wall in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. On the other end of the line was my friend Eric “DJ Strobe” Cohen, talking from his apartment on Second Avenue in New York City’s East Village.

“Uh, yeah, but we have to make sure we have an extra room for my music studio,” said Eric, “because that’s a source of additional revenue for me.”

“No worries, I’m down for that,” I noted. “We also need to make sure we have a spot for the turntables.”

Eric enthusiastically replied, “Oh yeah!”

CASE IN POINT

Growth Hacking in Hell’s Creative Kitchen

It was May of 1996. After bumming around for two years postcollege, trying to figure out the meaning of life (translation: waiting tables, DJing at a nightclub, doing freelance design work for small businesses, and basically trying to survive while living with my parents), a close colleague offered me a job doing international marketing for what seemed to me to be every unknown musician on the planet. It wasn’t a glamorous job, but it got my foot in the door. The industry was no stranger to me. I’d spent much of my time since 1991 as a radio and club disc jockey, and I’d been networking with a few in the industry on early Internet chat boards and via email.

So, when the call came with the salary offer ($350 a week, no benefits), all I needed to do was find an affordable place to live. Enter my buddy Eric.

The place we eventually found was in Hell’s Kitchen, at the time a pretty rough Manhattan neighborhood with a dark history. Inhabited by poor and working-class Irish Americans at the turn of the nineteenth century, it had been known for its Irish gangs and, even in the 1970s, as a place where both the Irish and Italian American mafias carried out hits.

Hell’s Kitchen at the time was nothing like it is today. On the night we moved in, we couldn’t leave our apartment because the police were carrying out a drug raid right outside. To us—two twenty-something members of the creative class—this was the perfect location to begin our future-of-work experiment.

Although Eric worked at a computer store by day, his real craft was as a music producer and DJ. In 2016, this fact barely registers—everyone under thirty is now a DJ/producer—but in 1996, the barrier to entry was formidable, especially when compared to today’s easy access via software and social networks.

Eric had a small one-room studio (literally our living room in the loft space we called home) in which he would produce, remix, and master recordings. There was no need for a high-end studio with lots of fancy equipment, since software and a few pieces of hardware were his main tools along with a good mixing desk, some audio plug-ins, a laptop computer, and high-end headphones.

In 1997, a major record label asked Eric if he would remix a song for one of its young singer-songwriters, Jennifer Paige. The label wanted different versions to give it more of a chance of being played on radio. Eric obliged and asked the label to send him the “stem” of the singer’s vocals. (A stem is a mixed group of audio sources.) Later, Eric and I had a good laugh over the fact that the label representative was clueless about what Eric wanted.

Eric didn’t need to meet the artist. He didn’t need her to re-record any vocals in the studio. All he needed was the original vocals so that he could produce an entirely new soundscape. Eric requested delivery via bike messenger of the vocal stem on digital audiotape so he could dump it into his software and build a whole new musical arrangement around the vocals.

Nowadays, a stem is not a big deal; artists regularly put stems up on YouTube so that any producer can download and remix their songs. Back then, in that Hell’s Kitchen apartment, we were almost twenty years ahead of the curve. Today, songs are remixed to piggyback off another more popular artist’s name. (As Pablo Picasso said, “Good artists copy but great artists steal.”) This is the essence of “growth hacking.” At the intersection of marketing and engineering, growth hacking is now being used by many startups to gain audience share.

In the late 1990s we were on the fringe of what has become the creative participatory (gig) economy that drives the world economy. No brands created this. In fact, corporations that try to enter it usually meet with distrust. A true community supports this world organically, and no brand can ever control it.

BRANDS AND CREATIVITY IN THE ANTI ORGANIZATION AGE

Do brands foster creativity? It’s doubtful. Despite all the articles online about how to foster a culture of creativity at brands, companies peddling products are the last place people turn for creative expression. On the other hand, brands could learn a lot from the outsider art.

Art has always been about what one feels and what one wants to express. It’s also about making a personal statement. Art contributes to the world around us when it makes people feel something as a result of their interaction with it. For decades, brands wanted their statement and narrative to be the only story that customers heard. For this reason, brands were at the forefront of de-emphasizing art. As far as they were concerned, it was unimportant to the sales process. In the early 1990s, with the rise of personal computing and software such as PowerPoint, organizations concentrated solely on value process, asking, “How do we sell us?” “How do we talk about us?” Most ad and marketing campaigns at that time were brand centered. The only art was found in slogans, like one from Pepsi that showed pop art versions of their cans and the tagline: “Our idea of pop art. New Cool Cans.”

That was in a read-only world. Yet despite the changes, many brands still don’t seem to understand that we now live in a read/write/remix world, and such narratives leave little space for creative expression or third-party partnerships. However, in 2013, art came roaring back into many marketing campaigns, including those for W Hotels, Lincoln cars, Ketel One Vodka, and Samsung Electronics. You could say that many on Madison Avenue were adopting the slogan Ars gratia artis, or “Art for art’s sake,” in order to speak the same language as a young generation that appreciated art as a common language.

Today, with platforms like Instagram, Snapwire, and Olapic ushering in creativity for any smartphone user, brands are beginning to backtrack and position themselves again in the middle of modern design and technology. After all, these actions now help generate revenue. For many brands, creative directors, and media, the appeal of using “social photography” for commercial purposes is growing. First, the variety of potential photos is nearly infinite, the visuals often have a personality or authenticity that traditional stock photos lack, and there’s plenty of opportunity for valuable engagement with fans and customers. Second, any mobile camera user can now be a photographer on behalf of the brand.

That said, does anyone really want to create brand art? For much of human history, economics de-emphasized making, creating, innovating, and producing art because it didn’t create capital. However, now that brands are moving away from capital as their main reason to exist, they are beginning to understand that creative imagery is a key piece in connecting with people. Could disruptive marketing help brands gain an advantage?

THE MOVE TOWARD THE CREATIVE ECONOMY

To better understand how we came to live in today’s creative economy, we need to understand the history and evolution of the economy at large.

The two driving principles of the industrial age were control and certainty. For businesses to control individual decision makers and create processes that could be repeated over and over for success, the idea of the corporation emerged. In what is considered by many to be the most influential management book ever written, 1956’s The Organization Man, William H. Whyte described the expansion of the corporate business model and explained why, in the post–World War II era, when Americans had shed the idea of rugged individualism in work, management and marketing organizations and groups could make better decisions than the individual.

With this in mind, it made the most sense from a career standpoint to serve the organization rather than one’s own creative passions and desires. The corporation acted as a shell to help businesses, which were inherently risk averse, manage in uncertain times. Whyte ripped heavily on the idea of risk averseness, noting that it creates workers who face zero consequences as long as they make no mistakes.

The scenario Whyte documented seems a far cry from how business operates now. Or is it? For some brands, you wouldn’t think they ever left the twentieth century—or 1956, for that matter.

For much of the twentieth century, the conventional wisdom was that the only thing required for success in business was to synchronize systems. This idea is rooted in the left-brain thinking of the knowledge economy, a concept that cropped up as early as the 1960s. However, as W. Brian Arthur noted in Complexity and the Economy, “The world is to a large extent organic and algorithmic.” This is one reason super platforms that share vast amounts of information are more powerful than static websites. Having elements of organic sharing and algorithmic filtering in business is like the air and water necessary for life. Consequently, influence and reputation are the new currency. Brands are now tasked with creating objectives that capture the imagination of a new generation of customers.

The driving design principles of today’s transformative age are empowerment and opportunity exploitation. Structural change has become mandatory as a result of shifting behavioral and economic changes. There are just a few problems holding many companies back from this transformation. One is that they have failed to understand that, in the age of what many of us dub “cognitive capitalism,” the new economic system may not place as much emphasis on revenue as it does on persuasion and influence.

MARKETING IN THE AGE OF ABUNDANCE

In their sprint to force demand for their products, conventional marketers seem to forget one thing about this new reality: information is abundant. Even physical goods and intellectual property are free. Paul Mason, journalist for the Guardian, explains it this way:

We’re surrounded not just by intelligent machines but by a new layer of reality centered on information. Consider an airliner: a computer flies it; it has been designed, stress-tested and “virtually manufactured” millions of times; it is firing back real-time information to its manufacturers. On board are people squinting at screens connected, in some lucky countries, to the internet. Seen from the ground it is the same white metal bird as in the James Bond era. But it is now both an intelligent machine and a node on a network. It has information content and is adding “information value” as well as physical value to the world. On a packed business flight, when everyone’s peering at Excel or PowerPoint, the passenger cabin is best understood as an information factory. But what is all this information worth? You won’t find an answer in the accounts: intellectual property is valued in modern accounting standards by guesswork. A study for the SAS Institute in 2013 found that, in order to put a value on data, neither the cost of gathering it, nor the market value or the future income from it could be adequately calculated. Only through a form of accounting that included non-economic benefits, and risks, could companies actually explain to their shareholders what their data was really worth. Something is broken in the logic we use to value the most important thing in the modern world.

In other words, since the advent of the web in the early 1990s, and the social web in the early 2000s, as well as the Internet of Things, which will arrive in the next ten to fifteen years, economics has been centered on a condition of scarcity. Yet the most dynamic force facing the modern world is an abundance of information and solutions. This is a curse to brands that think they have the only product worthy of a customer’s attention. And it’s a curse to brands that still believe they need only a handful of channels to promote their products, solutions, and messages.

In 1960, there were only five marketing channels, but as of this writing, there are more than seventy. If we apply Moore’s Law to marketing channels, this number will double or triple every two years.

The Impact of Loss of Control over Marketing Channels

The other underlying issue—the bigger one, in fact—is that corporations are not structured to endure these ongoing changes, especially in marketing. Brands have little control over these marketing channels because users will interact with one another before they will interact with a company. The corporation along with the conventional marketing mindset is designed to avoid radical shifts and to incrementally deal with these scenarios. Their DNA is not built on a double helix structure that contains the elements of transformation and reimagination found in startups.

As a result, the majority of corporations miss out on the opportunities that exist in the creative economy. They wouldn’t even know how to find an Eric in his Hell’s Kitchen apartment or how to program a music channel for their brand on Spotify, or how to engage in any cultural marketing because—to conventional thinkers—activities like this don’t drive revenue.

If corporate brands were the only players in our global economy, I would tell them not to sweat it. But the economy isn’t made up solely of multinational corporations. Small and startup businesses, which drive the most economic growth, are ever more capable of taking advantage of the creative economy. Their DNA isn’t wired like a large company’s. They may have issues of their own—scarcity of financial resources, for example—but that can be an advantage in a world filled with an increasing number of “freemium” growth empowerment options, software to scale, and attention-grabbing nurture streams.

Geoffrey Colon |

|

Corporations are risk averse. This is a disadvantage in the creative economy. #disruptivefm

6:32 PM—21 Feb 2016

We know that the brands of the future will look a lot different from the brands of today. However, many brands are taking a long time to figure out exactly what they will look like. And all the while, the clocks are ticking and the business models are being burned to the ground. We know that over the next twenty years, machine intelligence will play a much larger role in value creation. Mobile devices and the Internet of Things will change how we engage with others.

It is only by algorithmically programming all the routine processes that organizations will be able to free up the creative space for differentiated and innovative offerings. The time previously spent “managing machines” and pouring resources into operations will be repurposed into creative output. This is one reason companies that put more emphasis on free time to explore ideation and innovation have an added advantage in the new economy. Reshaping the economy from one based on knowledge to one based on creativity also involves reshaping the way marketing will work.

In 2014, I created a spreadsheet to document the amount of time I spent on three areas of my business: creative, operations, and management. The first area covered any creative input or output to drive my business. The second dealt with time sheets, invoices, purchase orders, and so on. The third dealt with managing my team. Here’s what that chart looked like, based on forty-seven sixty-hour workweeks:

TOTAL HOURS WORKED = 2,820

![]() Creative = 282, or 10 percent

Creative = 282, or 10 percent

![]() Operations = 1,692, or 60 percent

Operations = 1,692, or 60 percent

![]() Management = 846, or 30 percent

Management = 846, or 30 percent

I put the most time into the operational side of the business and the least into creative. Wouldn’t it make more sense if my time as a marketer—mainly a creative and artistic field intermixed with data—took up 60 percent of my time and the operational took up 10 percent? Shouldn’t the time spent on these two areas be flipped? Big companies are at a major disadvantage when they compete in the creative economy when they have scenarios like this!

In 2014, I had the privilege of taking part in the Kellogg School of Management certification program at Northwestern University. It was a wonderful experience. Professors broke down some of the things that all organizations must contend with in moving forward. The media are no longer in the hands of the few but, rather, are distributed among the many. As a result, how we use media—and especially imagery—has become the new creative activity. In the words of Lawrence Lessig, author of Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy, “Knowledge and manipulation of multi-media technologies is the current generation’s form of ‘literacy.’”

Guy Debord, author and Marxist critical theorist, foreshadowed this in his 1967 critique, The Society of the Spectacle, in which he wrote that images had supplanted genuine human interaction. “All that was once directly lived has become mere representation.” We can see much of this in how we interact on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram.

WHAT “UNICORNS” KNOW ABOUT THE CREATIVE ECONOMY

Conventional marketers and brands use these social media platforms as they were built to function. Disruptive marketing takes it a step further and asks, “If the economy is being reshaped to focus on living rather than on having, what image should we use to convey this enchanted state?” That is, if in a consumer society social life is not about living, but about having, in an immersive creative society, social life is about individuals making and producing, and receiving commentary and feedback from the crowd by using a variety of communication platforms.

Geoffrey Colon |

|

The creative economy is about making things and experiences, not simply consuming and having things. #disruptivefm

6:33 PM—21 Feb 2016

This leads us to a whole new era in the history of civilization. There is no past knowledge from which to draw as we plot the future. This is a difficult problem for the corporate branding model, which uses past data to shape its next moves. Conversely, it gives an advantage to those with creative thinking skills, especially disruptive marketers, especially those with the imagination to paint on a blank digital canvas that correlates with the daily business plan motto: Don’t plan more, do more.

At the same time as we are transforming from an analog to a digital world, we are also accelerating from a knowledge economy to a creative participatory economy. In knowledge-based economies, people are paid to think of linear left-brain answers to complex scenarios. Engineers analyze data and come up with a process, equation, or product. However, because of the massive growth of the web—and specifically search engines like Bing—we rely less on knowledge transfer because everything we need to know can be found with the swipe of our finger on any connected device. Only the most complex issues remain unsolved, and in the next fifty years many of those may well be solved as well.

As a result, the knowledge economy is ceding to a more powerful yet even more complex cognitive, creative economy. John Howkins describes the nature of this economy in his book The Creative Economy:

The creative economy consists of the transaction in . . . creative products. Each transaction may have two complementary values, the value of the intangible, intellectual property and the value of the physical carrier or platform (if any). In some industries, such as digital software, the intellectual property value is higher. In others, such as art, the unit cost of the physical object is higher.

If you consider what Howkins is saying, and then look at the stock market and analyze why companies like Facebook, Microsoft, Google, and Apple are so highly valued, you will soon realize it’s because their business models have crossed the chasm into this new era. The same can be said about several billion-dollar valuated startups (dubbed “Unicorns,” in Silicon Valley tech slang) that understand and have implemented this premise.

Disruptive Marketing in the Creative Economy

It’s important to understand how this balance of power is shifting if you are to embrace disruptive marketing in the creative economy. If you sell based on product features, the product gets lost in a field of lookalikes, knockoffs, and re-engineered goods, whereas brands positioned as services—as opposed to products—will stand out from the crowd.

People are looking for experiences, emotions, and feelings, not products, features, or price points. And the web acts as a feedback loop where everyone can find data they can apply to their decision-making process.

Consider how politics is being reshaped in this creative economy. Why aren’t middle-of-the-road ideologies good enough for citizens anymore? Is it possible that radical ideas from both the left and right edges of the political spectrum are seeping into the consciousness of the general population because incremental change is no longer fast enough? Is this a global trend? Are people worldwide yearning for the fringe? It seems people won’t settle for the way things have always been done. Especially from bland brands.

Richard Florida, author of The Rise of the Creative Class, offers another explanation for why branding is shifting. A large percentage of the world’s economy is now made up of the “creative class,” a highly educated and mobile workforce that, in the past, had been highly sought by brands and advertisers alike. (The other two classes noted by Florida are the “working class” and the “service class.”) In an era in which media had yet to fragment, it was easy to reach this audience via media planning, ad buying, and brand messaging. However, Florida gives good economic reasons for the need to pivot brand marketing in the twenty-first century to meet this customer-centric emerging class. Florida explains:

[T]he Creative Class is the norm-setting class of our time. But its norms are very different: Individuality, self-expression and openness to difference are favored over the homogeneity, conformity and “fitting in” that defined the organization age. Furthermore, the Creative Class is dominant in terms of wealth and income, with its members earning nearly twice as much on average as members of the other two classes.

The New Creative: How We Use Media

The mass media have always held the power for the conventional brand marketer. But for the disruptive marketer, it’s simply something to hack into and use in new and imaginative ways. In his 2006 book, An Army of Davids: How Markets and Technology Empower Ordinary People to Beat Big Media, Big Government and Other Goliaths, Glenn Reynolds notes how technological change has allowed people more freedom of action in contrast to the “big” establishment organizations that used to function as gatekeepers. The balance of power is flattening out into a more and more level playing field. As a result, how we use media to reach our customers in an attention-deficit economy becomes more imaginative, depending on how we disruptively engage with it.

In 1990, when I entered Pennsylvania’s Lehigh University, the library gave me an email address. I used that address quite a bit to send electronic mail to other students and professors. Yet even more exciting than electronic mail was having access via one portal in the college newspaper (The Brown and White) newsroom to the World Wide Web. As early as 1991, I would log in and surf it daily to see what was going on in the world. There weren’t many websites at that time. If the information existed, and you could find it (which was easy because there was a finite amount of data), you could find answers. Nevertheless, I still relied on gatekeepers who amplified their voices via print media.

Fast-forward to 1998, when much of the information that was available in the physical world became available online. However, the infrastructure was not yet strong enough to support the potential of this new commerce ecosystem. That is, the world was not as mobile as it is today. However, from the ashes of the dotcom era rose today’s web 2.0 and the interconnected social web. Data is plentiful. In fact, Google’s Eric Schmidt said in 2010, “Every two days we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilization up until 2003. That’s something like five exabytes of data.”

Much of this data is user-generated content (UGC) in the form of photos, videos, graphics, GIFs (graphics interchange format), and memes. As marketers, we compete against it, even beyond our normal business competition. Conventional marketing, with its stale messages about value propositions and its narratives about the company’s vision, simply won’t cut it anymore; those messages are unlikely to be seen, heard, or, most important, felt in this noisy space.

It’s the Creative Economy, Stupid!

In early 1992, James Carville, then presidential campaign adviser for Arkansas governor Bill Clinton, hung a sign on a wall in the Little Rock headquarters. His candidate trailed in the presidential race by 30 percentage points. On that paper were three items:

1. Change vs. more of the same.

2. Don’t forget health care.

3. It’s the economy, stupid.

What was meant for an internal audience tipped into the external and became a rallying cry. Ten months later, Clinton ousted incumbent George H. W. Bush for the presidency.

Carville gained the attention of a population mired in a poor job market and won their hearts and minds through a slogan. It was a simple message, but one that was easily carried in the pre-social web word-of-mouth era.

If that same message was delivered today, it would barely travel past the end of the block, primarily because it lacks creative and immersive UGC to support it. Slogans and words without customer participation are lost on inattentive minds. Unless those words are attached to people we know and trust, we tune them out, just as we would tune out an annoying radio commercial on WEAF-AM.

If today, Carville gave that slogan to a group of “influentials” who were rabid Clinton supporters and said, “I don’t care what you do; here’s what we believe,” those supporters would turn that message into something far more powerful. The story and outcome would be different because each person interprets messages differently and makes them personal based on his or her belief system. Once the message is personal, people identify with it.

CREATIVE MARKETING LESSONS FROM #FERGUSON

It was August 9, 2014. I remember the date because I had just finished wishing my older brother Brian a happy birthday. It was close to 1 AM Eastern Time. I wanted to know what the weather was going to be like in Seattle the next day, but before I checked, I peered at my phone to see what was trending on Twitter.

In third or fourth spot was #Ferguson.

Curious what #Ferguson was about, I clicked on it. I had read in the news earlier about a policeman having shot a civilian, and now it appeared that citizens were taking to the streets in protest. Without many mainstream news sources telling me what was going on, I simply followed the tweets from regular people who were in Ferguson, Missouri, that night. Some of them were horrifying.

That night I turned to all the mainstream news outlets to see what they were doing or saying about the events. None of the major cable news outlets—CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News—were talking about Ferguson. In fact, it took almost another week for those outlets to note what was going on there. But their narrative was too late; by then, citizens had set the tone for the events.

I felt the official news reporters weren’t asking questions in an objective manner.

Ferguson, the Black Lives Matter movement, and Occupy Wall Street are good examples of disruptive marketing. Yes, I know what you are saying: “But what are they selling? What is the profit motive?” Earlier I said you must remove both feet from the twentieth century and put them squarely into the twenty-first. Do it now, and you’ll see how both disruptive marketing and movements like these are more about collaborative communications than about products or profits.

The Disadvantages of Organizational Models

In the experience economy, anyone can bring attention and meaning to events, messages, and experiences. No longer are these functions the job of a centralized organization. Because disruptive marketers understand this, they design noncentralized hierarchies to help spread the information created by others.

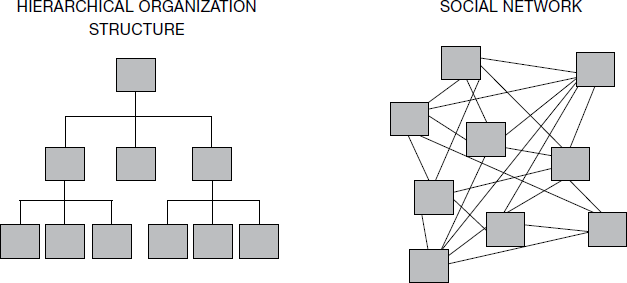

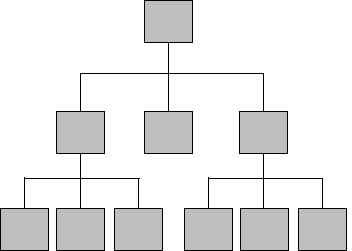

To demonstrate this, let’s first take a look at Figure 3-1 which explains organizational models, and then look at decentralized movements like #BlackLivesMatter to see why they are more effective than centralized and controlled brand-marketing campaigns.

The Figure 3-1a model is an organizational hierarchy common to many companies. In a marketing organization, the chief marketing officer (CMO) usually owns the top spot. Below that position are a number of disciplines that control the outputs of siloed groups, such as digital, brand, and social. The hierarchy model doesn’t have much intergroup interaction. Nor does it allow for the free flow of information from the bottom up or from other groups or teams within the company. Consequently, many good ideas never see the light of day.

Geoffrey Colon |

|

Hierarchies are for the military, not modern businesses or relationship marketing models. #disruptivefm

6:34 PM—21 Feb 2016

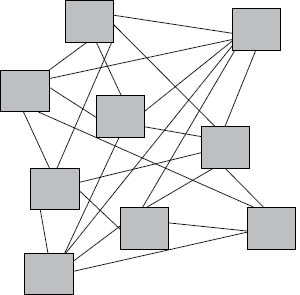

Figure 3-1: Conventional Marketing Organization Model vs. Social Network Model

Figure 3-1a: Conventional Marketing Hierarchy

Figure 3-1b: Social Network Business Model

The Figure 3-1b model is a disruptive marketer’s playground, on the other hand. In this social network model, anyone and everyone—especially external audiences—owns the messages and can create solutions.

When people ask how organizations can operate without a central leadership figure, what they miss is that central leadership figures (CMOs, in this case) rarely have much, if any, creative power because they spend most of their time on operations and people management. But in a networking model where operations are spread out, good ideas have a better chance of being accepted and adopted quickly and organically.

The Advantages of Decentralized Movements

Black Lives Matter and Occupy Wall Street are often thought of as “decentralized” movements. They don’t rely on a leader—and for good reason. Usually, when leaders leave organizations others leave, too. In the case of the social network model (Figure 3-1b), when a top leader leaves the messaging doesn’t lose momentum. There are others still generating content and experiences without the need for a “chief” officer to make that happen.

Geoffrey Colon |

|

Savvy marketers understand a social business model helps them do more with less. #disruptivefm

6:34 PM—21 Feb 2016

Conventional marketers usually rely on antiquated communication systems like email or even the telephone. The social network model, however, relies more on a business model in which tools like Slack, Yammer, and Jive replace email. Conventional marketers are still relying too much on linear and one-to-one tactics, rather than employing dynamic and many-to-many strategies that help carry messages.

Although it may look as if the sort of instability that a social network model presents will fail, because it lacks a defined and rigid organizational hierarchy, leadership actually plays a bigger role by making sure the organic messages that are created find their way to more people.