Introduction to Internet Crime

This chapter introduces the prevalence of crime committed on the Internet. It utilizes the available studies and reports commissioned by various companies, organizations, and the US government to articulate the Internet crime problem.

Key Words

Internet crime; HTCIA; Norton; Computer Security Institute; Federal Bureau of Investigation; Internet Crime Complaint Center

The Internet is like a giant jellyfish. You can’t step on it. You can’t go around it. You’ve got to get through it.

(John B. Evans, former senior News Corporation executive and pioneer in electronic publishing, 1938–2004)

In less then 20 years, the Internet has affected every element of modern society. Worldwide Internet usage increased from almost nothing in 1994 to nearly 2 billion users worldwide at the start of 2012 (Figure 1.1). Seventy-eight percent of North Americans were online in 2011. The current social networking leader, Facebook®, had over 800,000,000 worldwide users on March 31, 2012 (At the time of publishing Facebook according to their website has over one billion users). The Americas alone had over 300 million Facebook® users (Internet World Stats, Usage and Population Statistics, 2012).

Figure 1.1 Internet users in the world by geographical regions—2011. Source: Internet World Stats—www.internetwordstats.com/stat.htm

Internet connectivity is, however, not limited to just humans. In 2008, the number of things connected to the Internet, exceeded the Earth’s human population. Evans (2011) noted “these things are not just smartphones and tablets. They’re everything.” He cites as an example a Dutch start-up company using wireless cattle sensors to report on each cow’s health. Similar medical sensors are being developed for humans. For years many automobiles have been connected to the Internet. By 2020, he notes there will be an estimated 50 billion devices connected to the Internet (Evans, 2011).

Expanding Internet connectivity has been extremely beneficial to many human endeavors, such as communication, education, commerce, transportation, and recreation to name a few. Unfortunately, criminals have also found ways to take advantage of the Internet’s benefits, such as increased opportunities to find and target victims. This translates into a higher likelihood that an Internet crime victim will be walking in the doors of the world’s “brick and mortar” police departments.

Defining Internet crime

Criminal acts on the Internet are as varied as there are crimes to commit. In the Internet’s early years, the notorious criminals were the Kevin Mitnicks1 of the hacker world. Common then was the breaking into phone service and social engineering their way into computer networks. Today hacking has been brought to the masses with the introduction of various “crimeware,” malicious code designed to help the average criminal automate his attacks. But what does the term cybercrime mean? A broad definition would be a criminal offense that has been created or made possible by the advent of technology, or a traditional crime which has been transformed by technology’s use. Internet crimes by definition are crimes committed on or facilitated through the Internet’s use. There is often an over use of the term cybercrime to be all inclusive of many Internet crime categories, including computer intrusion and hacking. Texts have been devoted to the investigation and prevention of computer intrusions and hacking. This book’s primary focus is to provide law enforcement with the basic skills to understand how to investigate traditional crimes committed on the Internet.

Internet crime’s prevalence

Internet crime estimates vary widely depending on the data collection method. Most studies are done through surveying victims and businesses in an attempt to quantify the actual scope of the problem. The Computer Security Institute (CSI) Computer Crime and Security Survey2 solicits information from security experts. Symantec/Norton™ Cybercrime Index interviews individuals on their victimization. The High Technology Crime Investigation Association (HTCIA) solicits input from its members, who are made up of law enforcement, corporate, and private investigators, on cybercrime. Other studies look at investigative data, such as Verizon Data Breach Reports. Others collect data concerning specific incidents, such as McAfee Threats Reports, which cover malware3 incidents. Some are concerned with the data collection methods used by many of these studies. After all why would a company selling security products report anything but a high incidence of cybercrime? Normally crime data is collected by law enforcement or criminal justice agencies who presumably do not have a profit motivation.

US crime statistics are reported on a national level by individual law enforcement agencies to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under the uniform crime reports (UCR) process. Data is collected on crimes committed by law enforcement agencies under specific guidelines and forwarded to the FBI. The FBI compiles the data and publicly discloses the information in its annual crime reports. Current UCR data collection efforts do not focus on “high-tech” offenses, such as hacking and computer intrusions. There is a hesitancy by some to report cybercrime to the authorities. Publicly traded companies are reluctant to supply information on cyber-incidents fearing such disclosures will damage their image, negatively affect stock prices and/or spark lawsuits (Lardner, 2012).

The reporting requirements also do not mandate the reporting of any information about crimes committed on the Internet or whether a computer was used in the offense. Goodman (2001) points out that those traditional offenses may be classified under something that does not reflect the presence of a computer or Internet use. For instance, an Internet fraud scheme might be classified as a simple fraud. Additionally, cyberstalking might be classified as a criminal threat offense or stalking case.

One ironic data twist concerns sexual enticement cases. These cases are frequently undercover sting operations, in which the suspect believes he4 is communicating via the Internet with a minor. In reality there is no minor. The suspect makes online sexual comments, including his desire to have sex with the fictitious minor. The suspect is arrested when he goes to meet the “minor.” This crime is likely to be classified as sex crime even though there is no real minor or even victim. This is not to minimize the offense’s seriousness or to argue that it should not be counted as sex offense. The computer element and Internet use in this type of offense is clearly apparent and is largely being ignored in the data collection. It is an Internet-based crime but classified as a sex crime where no victim ever existed. This lack of clarity can have important implications for officers attempting to secure resources and training to properly investigate Internet crime.

It is also possible to look to media reports on cybercrime. The important caveat is that such reports tend to focus on the sensational and may not be representative of the vast majority of cybercrime cases. A case may make the headlines because it was novel or was particularly heinous, harmful, or otherwise “newsworthy.” Such crimes may have been isolated incidents and not the norm.

The above realities make it difficult but not impossible to determine the scope of the Internet crime. We obviously can’t definitively state the exact number of Internet crime victims, their actual loss, or even how many possible online criminals are preying on our citizens. We can, however, get a broad outline of Internet crime’s prevalence in our society by examining numerous data sources.

CSI 2010/2011 Computer Crime and Security Survey

The CSI has been a leading educational membership organization for information security professionals for over 30 years. Their study involves sending surveys by post and email to security practitioners. In the 2011, CSI sent out 5,412 such surveys to its members with a total of 351 returns or a 6.3% response rate. The survey looked at the period June 2009 to June 2010. Some of the major findings were as follows:

• Approximately 67% noted malware infections continued to be the most commonly seen attack;

• Almost half the respondents experienced at least one security incident. Slightly more than 45% of these respondents indicated they had been the subject of at least one targeted attack;

• Slightly more than 8% reported financial fraud incidents, which was down compared to previous years;

• At the same time fewer respondents than ever were willing to share specific information about dollar losses suffered (CSI, 2011).

Norton™ Cybercrime Report 20115

Symantec provides information security solutions including software, commonly referred to as Norton™ anti-virus and anti-spyware. Symantec under the trade name Norton™, surveyed a total of 19,636 individuals in 24 countries6 from February 6, 2011 to March 14, 2011. The survey participants included 12,704 adults (including 2,956 parents), 4,553 children (aged 8–17), and 2,379 teachers (of students aged 8–17). Participants were asked if they ever experienced one or more of the following: a computer virus or malware appearing on their computer; responding to a phishing7 message thinking it was a legitimate request; online harassment; someone hacking into their social networking profile and impersonating them; an online approach by sexual predators; responding to online scams; experiencing online credit card fraud or identity theft; responding to a smishing8 message or any other type of cybercrime on their cell/mobile phone or computer. The survey found that more than a million individuals become a cybercrime victim every day. Fourteen adults become a cybecrime victim every second. The top three cybercrimes were computer viruses/malware (58%), online scams (11%), and phishing (10%). Ten percent of the online adults indicated that they experienced cybercrime on their mobile phone (Symantec, 2011).

The Norton™ study also did some data extrapolation and determined the financial losses due to cybercrime to be $114 billion annually. Additionally, they estimated the dollar figure for time individuals lost due to their victimization to be $274 billion. They combined these two amounts for an annual global cybercrime cost of $388 billion. They further noted that this cost was more than the combined global black market in marijuana, cocaine, and heroin ($288 billion) (Symantec, 2011).

HTCIA 2011 Report on Cybercrime Investigation

HTCIA is the largest worldwide organization dedicated to the advancement of training, education, and information sharing between law enforcement and corporate cybercrime investigators. Its over 3,000 members are located in 41 chapters worldwide. Eight-five percent of the membership is located in the United States, with 14% located in other countries, including Canada, Europe, the Asia-Pacific Rim, and Brazil. Since 2010, HTCIA has annually solicited input on cybercrime from their membership. In 2011, 445 members responded to the survey. The 2011 Report found:

• An increase in criminal use of digital technology: Members reported increases for the second year in a row in all four ways computers and/or the Internet are used to commit crime, specifically: for research or planning to commit the offense, as a direct instrument in the offense, as a communication device between offenders and/or victims, and as a record keeping or storage device.

• Improvement needed in information sharing: Members noted that a lack of resources has made it harder for investigators to collaborate and share information.

• Better training at multiple levels needed: Members reported that civilians, judges, prosecutors, and even middle and upper level management have a hard time understanding cybercrimes’ complexities.

• Better reporting, strategy and policy needed: Members recognized the continuing problem of no uniform mechanism for cybercrime reporting.

• Perhaps more importantly members noted that law enforcement agencies and corporations may have widely divergent policies and strategies based on the extent to which they understand the cybercrime problem.

McAfee® Threats Reports

McAfee® is a wholly owned subsidiary of Intel® Corporation and is leader in anti-virus software. It has a lab which studies the detection of new and evolving online threats and provides threat assessments on a quarterly basis. In 2012, they reportedly had 100 million pieces of malware in their “zoo.” These threats are important for the investigator to be aware of, not only for understanding Internet crime but to remain virulent during online investigations. As the 2012 First Quarter Threats Report notes “The web is a dangerous place for the uninformed and unprotected.” Some of the 2012 trends noted were as follows:

• Data breaches by the third quarter of 2012, reached an all time high, exceeding all of 2011 figures.

• Increases in active malicious uniform resource locators (URLs)9 were noted with almost 64% of newly discovered suspicious URLs located in North America. By September 2012, McAfee® had identified 43 million suspicious URLs.

• The United States is frequently the location of both the attacker and target of attacks. Additionally, the United States was most often noted as location of newly discovered botnet10 command servers.

• Malware trends included increasing targeting of mobile devices, notably Androids and Macintosh®11 computers. Additionally, Ransonware12 attacks were seen as growing.

• McAfee® detected a growth of established rootkits13 as well as the emergence of new ones. Of particular concern were the rebounding of password stealing Trojans.14

• They also observed global spam15 volume decrease but noted there were significant differences of volume by country. Some countries, such as South Korea, Russia, and Japan, saw decreases while others saw increasing volumes. For instance, Saudi Arabia saw a spike in August 2012 of more than 700%. The most common spam subject line involved drugs.

• McAfee® noted that botnet software was actively being marketed for as low as $450.00. One particularly rootkit program that McAfee® observed as a growing threat was Blackhole. Gallagher (2012) describes it as a “…web-based software package which includes a collection of tools to take advantage of security holes in web browsers to download viruses, botnet Trojans, and other forms of nastiness to the computers of unsuspecting victims. The exploit kit is offered both as a ‘licensed’ software product for the intrepid malware server operator and as malware-as-a-service by the author off his own server.” Cost ranges from a 1-day rental of $50 up to a month-long lease of $500. Those interested in purchasing a 3-month license for their own sever (which includes software support) were looking at $700 up to $1,500 for a full year, plus $200 for the multidomain version. Special “site cleanup” package is priced at $300.

In 2012, McAfee® also observed not only malware’s use for profit but also cyberattacks in retaliation of such events, such as the release of YouTube anti-Islam video (Poeter, 2012). They concluded that estimating and understanding the growth of malware is a continuing challenge, in part due to the differences in enemy motivations. We will go into more detail about this idea in the next chapter, suffice to say the 2012 Third Quarter Report notes:

Where our industry lacks insight is into the conditions and motivations of the enemy; today’s cybercriminals and other classes of attackers. Cyber-criminal’s motivations are pretty straightforward, making money from malware and related attacks. This goal yields malware of certain types and functionalities. However, with hacktivist or state-sponsored attacks, their motivations and goals are completely different. Thus the code and attacks will be of a very different order. These underlying dynamics lead to the wide swings in sophistication we see in many classes of malware and attacks. Cybercrime malware exhibits far different behaviors than Stuxnet, Dugu, or Shamoon because the goals of the attackers are different: Cybercrime malware seeks a profit and (form the most part) stealth: Stuxnet and Dugu are concerned with sabotage and espionage; and Shomoon sows chaos and destruction (McAfee®, 2012, p. 9).16

2012 Data Breach Investigations Report

This study was conducted by the Verizon RISK Team17 with cooperation from the numerous law enforcement agencies.18 This study was based upon “…first-hand evidence collected during paid external forensic investigations conducted by Verizon” and data submitted by the law enforcement based upon their investigations. Unlike the other studies, this one focuses solely on data breaches. In 2011, the study looked at 855 incidents, involving 174 million compromised records, which was the second-highest data loss since they started keeping records in 2004. The study found that 98% of the breaches were from outside agents. Eighty-one percent involved some form of hacking and 69% incorporated the use of malware. Most profound was the report’s Executive Summary which noted:

The online world was rife with the clashing of ideals, taking the form of activism, protests, retaliation, and pranks. While these activities encompassed more than data breaches (e.g., DDoS attacks), the theft of corporate and personal information was certainly a core tactic. This reimagined and reinvigorated specter of ‘hacktivism’ rose to haunt organizations around the world. Many, troubled by the shadowy nature of its origins and proclivity to embarrass victims, found this trend more frightening than other threats, whether real or imagined. Doubly concerning for many organizations and executives was that target selection by these groups didn’t follow the logical lines of who has money and/or valuable information. Enemies are even scarier when you can’t predict their behavior.

Internet Crime Compliant Center

In June 2000, a partnership between the FBI and the National White Collar Crime Center (NW3C) was created “…to serve as a means to receive Internet-related criminal complaints and to further research, develop, and refer the criminal complaints to federal, state, local, or international law enforcement and/or regulatory agencies for any investigation they deem to be appropriate.” From this partnership, the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3)19 was eventually formed (IC3, 2011).

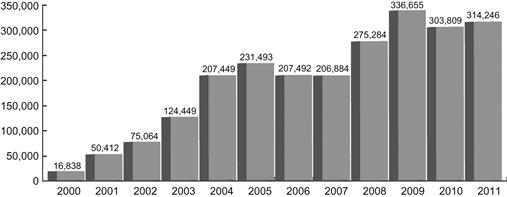

One function of the IC3 is to analyze and report on the online victimization complaints received. During 2000, its first year of existence, 16,383 complaints were received. Unfortunately, there has been an almost steady increase in the complaints received since then (Figure 1.2). In 2011, 314,246 complaints were received. These complaints involved an adjusted total dollar loss of $485.3 million. Additionally, 2011 marked the third year in a row that IC3 received over 300,000 complaints, which was a 3.4% increase over 2010 (IC3, 2011).

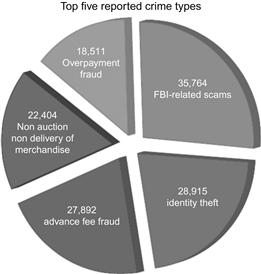

The vast majority of complaints were fraud related with FBI-related scams being the most prevalent. The IC3 reported the following top five crime categories in 2011 (Figure 1.3):

• FBI-related scams: Offenses in which the suspect posed as the FBI to defraud victims.

• Identity theft: Unauthorized use of a victim’s personal identifying information to commit fraud or other crimes.

• Advance fee fraud: Suspects convince victims to pay a fee to receive something of value, but do not deliver anything of value to the victim.

• Non-auction/non-delivery of merchandise: Purchaser does not receive items purchased.

• Overpayment fraud: An incident in which the complainant receives an invalid monetary instrument with instructions to deposit it in a bank account and send excess funds or a percentage of the deposited money back to the sender.

Internet harassment

Noticeably absence from the 2011 Internet Crime Report are incidents concerning cyberharassment, cyberbullying, and cyberstalking, which Smith (2008) collectively refers to as Internet harassment offenses. Cyberbullying and stalking have become regular events that require significant investigative attention. Cyberbullying has become publicly significant due to the number of teenagers who have committed suicide over Internet harassment and comments posted online about them. Baum, Catalano, Rand, and Rose (2009) note that approximately 3.4 million people are stalked annually and one in four victims report that the offense includes a cyberstalking act. Law enforcement estimates that electronic communications are a factor in 20–40% of all stalking cases (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2009). Cyberstalking victims report that 83% of the perpetrated acts are via email and 35% are via instant messaging (Baum et al., 2009).

Traditional crimes and the Internet

Kaspersky (2012) recently noted that “social media is the latest tool in the arsenal of cybercrimes, with groups using social networking websites, such as Twitter, to ‘manipulate the masses’ into thinking a certain way” (Barwick, 2012). Cellular telephones, particularly through their easy access to social media, have added another dimension to the investigation of Internet crime. In 2011, we saw the coordination of mass mayhem via “flash mobs” or “flash robs,”20 through the use of cell phones and social media by individuals in the United Kingdom and the United States (Pinkston, 2011). One parole officer found through a mobile phone examination and checking a social networking site that a violent offender was participating in a gang called M.O.B. (Money Over Bitches), which involved individual pimps trading prostitutes on the west coast (Korn, 2011). The connection of the Internet through cell phones is also becoming a prevalent communication method for gangs. The 2009 National Gang Threat Assessment reflects:

Gang members often use cell phones and the Internet to communicate and promote their illicit activities. Street gangs typically use the voice and text messaging capabilities of cell phones to conduct drug transactions and prearrange meetings with customers. Members of street gangs use multiple cell phones that they frequently discard while conducting their drug trafficking operations. For example, the leader of an African American street gang operating on the northside of Milwaukee used more than 20 cell phones to coordinate drug-related activities of the gang; most were prepaid phones that the leader routinely discarded and replaced. Internet-based methods such as social networking sites, encrypted email, Internet telephony, and instant messaging are commonly used by gang members to communicate with one another and with drug customers. Gang members use social networking Internet sites such as MySpace®, YouTube®, and Facebook® as well as personal web pages to communicate and boast about their gang membership and related activities (p. 10).

Sex offenders have been using the Internet, almost since its inception to view, store, produce, receive, and/or distribute child and other forms of pornography; to communicate, groom, and entice children and others for victimization; and to validate and communicate with other sex offenders. Since 2007, MySpace® has reportedly removed 90,000 sex offenders from its social networking site (Wortham, 2009). Facebook® prohibits sex offenders from accessing their site. Major dating sites are moving to screen sex offenders from their membership (NYDailyNews.com, 2012). Legislatures in many states are working to make it illegal for a sex offender to access social networking sites that may be used by minors (Bowker, 2012a,b).

Countless criminals have also been caught after boasting about their illegal activities online. In December 2011, three “geniuses” were caught after two of them were bragging about their bank robbery on their Facebook® profile wall (Hernandez, 2011). Another robber skipped out on supervision conditions and fled the jurisdiction, only to be later apprehended after his taunting Facebook® posts lead officers to his location (DesMarais, 2012). Others have logged into their social networking profiles from houses they are burglarizing or from stolen cell phones, which have lead authorities to their identity and arrest (DesMarais, 2012).

There have been numerous media reports of criminals using the Internet to attempt to intimidate or harass victims and/or witnesses. A Sarasota Florida woman was arrested after making threats on Facebook® against witnesses in her brother’s murder trial (Eckhart, 2012). One of the most brazen offenders was a Cook County burglar who would cyberstalk witnesses and victims, posting malicious allegations that they had committed criminal acts (Gorner & Meizner, 2012). In one incident, he ran online ads claiming a witness was running prostitution out of her home, resulting in several men erroneously knocking on her door thinking they had appointments. In one recent United Kingdom case, a convicted killer was accused of threatening a female trial witness by sending her Facebook® messages while he was incarcerated (Traynor, 2012).

Unfortunately, it is not unusual for inmates to have social networking profiles, which are oftentimes accessed through smuggled cell phones (Bowker, 2012a).

Investigators are also seeing the use of premade kits to commit crime on the Internet. Criminals can buy “crimeware” software that can enable them to commit crimes, hide themselves, and setup networks of computers to support their efforts. All of the efforts can then be funneled through online money exchange sites like Bitcoin to hide their profits from the authorities. This can make investigating these crimes difficult.

Investigative responses to Internet crime

Compounding the problem is how law enforcement and corporate investigators response to Internet-related crimes. There are over 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States. Most are small departments with little ability to respond to Internet-based crime. Some in fact still believe that crimes committed on the Internet are not their problems. “The Internet is not my Jurisdiction” was stated by a senior law enforcement administrator not so long ago. Many times the Internet is thought to be solely federal law enforcement’s purview and not local law enforcement’s responsibility.

Yet there are certainly many within state and local law enforcement agencies that understand the problem and are aggressively working on addressing segments of online crime. Particularly of note are the efforts of the Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) Task Forces nationwide. The ICAC is a federally funded program that is run by the state and local members of each task force. The program focuses on protecting children and finding and arresting those that would abuse and exploit them through the Internet. What is significant is that the program is run by the state and local investigators, and over the years they have developed a common national policy and procedures for their investigations of these crimes.

In the United States, there is no national cybercrime/cyber-terrorism reporting procedure or clearing house. This lack of a concise reporting process for victims, state and local law enforcement agencies, and the federal government leads to an under reporting of cybercrime and a true lack of understanding of the exact magnitude of the crime. To truly understand the significance of the cybercrime problem, a national plan to address law enforcements response and a method to measure the effects of the crime need to be implemented. The contributing factors that lead to continuing problems related to law enforcements’ response to cybercrime include:

• our ongoing national dependence on technology and the Internet;

• a lack of understanding of computer and Internet security risks by both users and law enforcement;

• a lack of funding for adequate network security and investigations tools;

• the ease of committing acts of terrorism or crimes through technology and the Internet;

• the continued difficulty in tracking the cyber-terrorist and cyber-criminal through the Internet;

• an inadequate national strategy to address cybercrime investigation;

All of this does not mean that law enforcement and corporate investigators have sat back and done nothing since the Internet went public. In fact pre-1994 law enforcement was well on its way to building responses to technology crime. In 1989, HTCIA was formed to bring law enforcement and corporate investigators together to fight technology crime. In 1990, the International Association of Computer Investigative Specialists (IACIS) was formed to train law enforcement investigators to examine computers and analyze digital evidence. Both of these organizations are leaders in the field of technology investigations and have greatly influenced the law enforcement response to cybercrime on an International level. The individual members have impacted cybercrime and have driven individual agencies response to cybercrime. This local law enforcement response has varied through depending on the agency and its leaderships’ understanding of the problem. Although things have improved over the past decade, there are still some law enforcement administrators that think the Internet is not their jurisdiction. Funding is a major problem associated with investigating cybercrime. Much of the local and state law enforcements response is dependent on the local funding for the problem. Nationally there has never been any consistent federal funding to local and state agencies to address the overall cybercrime problem. The US government as many governments around the world, have increasingly made cybercrime and cyber-terror investigations a priority. Federal agencies are recruiting engineers and computer scientists for their critical skills and they are dedicating more agents to cybercrime investigations. Throughout the last decade they have also created regional task forces across the nation to deal with the cybercrime issue.

Why investigate Internet crime?

Law enforcement for 30 years has understood the need to address crime in neighborhoods even at the lowest level. In 1982, a theory was introduced by George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson, which has been referred to as the “Broken Windows Theory.” They suggested:

… that “untended” behavior also leads to the breakdown of community controls. A stable neighborhood of families who care for their homes, mind each other’s children, and confidently frown on unwanted intruders can change, in a few years or even a few months, to an inhospitable and frightening jungle. A piece of property is abandoned, weeds grow up, a window is smashed. Adults stop scolding rowdy children; the children, emboldened, become more rowdy. Families move out, unattached adults move in. Teenagers gather in front of the corner store. The merchant asks them to move; they refuse. Fights occur. Litter accumulates. People start drinking in front of the grocery; in time, an inebriate slumps to the sidewalk and is allowed to sleep it off. Pedestrians are approached by panhandlers (Kelling and Wilson, 1982).

The theory espoused that even the small things in a neighborhood, such as abandoned property, unpicked weeds, and a broken window, would eventually lead to the disintegration of the neighborhood and eventually crime. What does a broken window have to do with Internet investigations? No we are not talking about the Windows operating system. The theory of small events and small crimes affecting the greater whole has the same effect on the Internet as it does in our own communities. The Internet is made up of various communities of interest. Social media has recently taken the lead as the most visible example. But, many Internet neighborhoods have had a few broken windows over time. Early in the Internet infancy, Usenet21 was a popular means of communication and community building. However, it disintegrated into an often vulgar and obscene place. People using the perceived anonymity of the Internet began to post pornography, bully other users, and basically act without any moral compass to guide them. This was the real wild west of the Internet that had no sheriff to police the community. Today’s Internet is no different in that sense. Certainly there are more efforts to police some areas of the Internet; however, there are more areas with broken windows. Internet relay chat, most of the social media space, and especially places like Tor’s hidden services continue the “wild west” atmosphere. The problem with all of these areas is the lack of the sheriff keeping the peace. Law enforcement has been mostly absent in many Internet areas. To address the ongoing Internet crime issues law enforcement and corporate investigators need to embrace the Vere Software catch phrase “Make the Internet your regular beat.”

What is needed to respond to Internet crime?

Both law enforcement and corporate investigators are constantly deluged with digital evidence issues in one form or another. The Internet continues to be a huge part of that evidence and investigative work load. So what will it take for investigators to make an effective response to Internet crimes? First of all you’ve taken the first step in reading this book. The other things that will make this job an easier fight are often not within the investigator’s control but they include some local and national initiatives to sort out the online investigation priorities. Investigators need to not only focus on their investigations but how their communities of interests are affected by the Internet and how they can prevent them from being victims of the Internet miscreants. Investigators can:

• help their communities and business understand the need to make network and desktop security a priority;

• ensure that all cybercrime instances are reported to local law enforcement agencies;

• develop better communication among Federal, State, and local law enforcement regarding cybercrimes investigation;

• make investigations on the Internet an everyday policing routine.

As a national approach investigators need to encourage several things through their individual management and politicians. These include:

• Development of a national multistakeholder approach to cybercrime investigation. Use the ICAC model as a guide to developing a national approach to investigating Internet crimes and uniform standards.

• Development of an interoperable international legal framework to aid in cybercrime investigations that crosses international borders.

• The development of tools needed to deal with cybercrime/terrorism investigations.

Continuing investigative problems

Until a national approach can be developed to deal with the problems associated with investigating Internet crimes, there will be continuing issues. Investigators and their managers need to understand that from an initial investigative point of view there is no difference between cybercrime and cyber-terrorism. This is because at the first complaint the investigator usually is not going to know the person’s motivation for committing the crime. The majority of online threats will continue to be cybercrimes, most of malware and intrusion attempts although cyber-terrorism, however, will be an emerging threat. To compound these response issues will be the continuing lack of coordination of US and International law enforcement agencies. Communications technology has a growing risk from cyber threats that become increasingly sophisticated, largely global and are organized businesses. There are no geographical borders, no boundaries to the information society. Vulnerability of the nation’s infrastructure is also increased as the use of communications technology becomes more prevalent.

Conclusion

The Internet has not changed the fact that crimes get committed and victims are created there every day. Information highlighted thus far reflects that Internet crime is as real as any committed on the street. Victims and losses are literally in the hundreds of millions. Malware attacks, followed by online scams, and phishing are probably the most prevalent type of Internet crimes. However, increasingly Internet crime is being perpetrated by “common criminals” and is no longer limited to just the techno criminal. Sex offenders are online. Gangs are using cell phones and social networking sites for criminal purposes. Mass attacks via flash mobs have been coordinated through cell phones and social media. Individuals are using the Internet to stalk, harass, and attack victims, including witnesses. Some offenders will even boast about their street crimes online. Victims, particularly corporations, are reluctant to report their victimization or the full extent of a cyber-incident.

However, no matter the location, crime needs to be reported and investigated. Internet crimes will continue to grow as we depend on the services it provides. More businesses will be victimized as they increase their online presence. What we hope to offer in this text is an opportunity for individual criminal and corporate investigators to expand their ability to respond to these crimes and offer more solutions than avoidance. The truth is that crimes committed on the Internet can be successfully investigated. Internet criminals can be found and prosecuted and victims can be gratified. What investigators need to understand is that they need to “make the Internet their regular beat.”22

Further reading

1. Barwick, H. (2012, May 23). Social media is a tool for cybercriminals says Eugene Kaspersky. Computerworld. Retrieved from <http://www.computerworld.com.au/article/425401/cebit_2012_social_media_tool_cyber_criminals_says_eugene_kaspersky/>.

2. Baum, K., Catalano, S., Rand, M., & Rose, K. (2009, January). Stalking victimization in the United States (NCJ 224527). Retrieved from U.S. Department of Justice website: <http://www.ovw.usdoj.gov/docs/stalking-victimization.pdf/>.

3. Bowker, A. (2012a, February 20). Why does your Facebook profile have an inmate number? Retrieved from <http://www.corrections.com/news/article/30208/>.

4. Bowker, A. (2012b, June 25). Three intriguing cyber-offender questions. Retrieved from <http://www.corrections.com/news/article/31038-three-intriguing-cyber-offender-questions/>.

5. Certified Forensic Computer Examiner. History. Retrieved from <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Certified_Forensic_Computer_Examiner/>.

6. Computer Security Institute (CSI). CSI 2010/2011 Computer Crime and Security Survey. Retrieved from <http://gocsi.com/survey/>.

7. DesMarais, C. (2012, June 24). Another crook caught because of posting on Facebook. PCWorld. Retrieved from <http://www.pcworld.com/article/258259/another_crook_caught_because_of_posting_on_facebook.html/>.

8. Eckhart, R. (2012, March 23). Tyson’s sister arrested over facebook post. Herald Tribune. Retrieved from <http://www.heraldtribune.com/article/20120323/ARTICLE/120329768/>.

9. Evans, D. (2011, July 15). The Internet of things [Infographic]. Retrieved from <http://blogs.cisco.com/news/the-internet-of-things-infographic/>.

10. Evans, J. Retrieved from <http://www.quoteland.com/author/John-Evans-Quotes/57/>.

11. Facebook®. Retrieved from <http://www.facebook.com/legal/terms/>.

12. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform crime reports. Retrieved from <http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/ucr/>.

13. Gallagher, S. (2012, September 12). BlackHole 2.0 gives hackers stealthier ways to Pwn. Ars Technica. Retrieved from <http://arstechnica.com/security/2012/09/blackhole-2-0-gives-hackers-stealthier-ways-to-pwn/>.

14. Goodman M. Making computer crime count. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 2001;70(8):10–17 http://www.c-i-a.com/internetusersexec.htm.

15. Gorner, J., & Meisner, J. (2012, April 26). Prosecutors say Kevin Liu was a prolific burglar who cyberstalked anyone who crossed him. Chicago Tribune. from <http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-04-26/news/ct-met-cyber-stalker-0426-20120426_1_prolific-burglar-cyberstalked-prosecutors>.

16. Gralla, P. (1996). How the Internet works (p. 55). Emeryville: Macmillan.

17. Hernandez, B. (2011, December 3). Don’t post ‘I’m RICH!’ on Facebook after robbing a bank. Retrieved from <http://www.nbcbayarea.com/blogs/press-here/Dont-Post-Im-RICH-on-Facebook-After-Youve-Robbed-a-Bank-134911353.html/>.

18. High Technology Crime Investigation Association (HTCIA). 2011 Report on Cybercrime Investigation: A report of the International High Tech Crime Investigation Association. Retrieved from <http://www.htcia.org/pdfs/2011survey_report.pdf/>.

19. Internet Crime Center (IC3). IC3 2011 Internet Crime Report. Retrieved from <http://ic3report.nw3c.org/docs/2010_IC3_Report_02_10_11_low_res.pdf/>.

20. Internet World Stats, Usage and Population Statistics. Retrieved from <http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm/>.

21. Kelling, G., Wilson, J. B. (1982, March). Windows: The police and neighborhood safety. Atlantic Magazine. Retrieved from <http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/03/broken-windows/4465/2/#/>.

22. Korn, P. (2011, July 7). County lab keeps cyber-eye on parolees technicians scour electronic devices for evidence of violations. Portland Tribune. Retrieved from <http://portlandtribune.com/news/story.php?story_id=130998904988341200/>.

23. Lardners, R. (2012, June 29). Cybercrime disclosures rare despite new SEC rule. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved from <http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Cybercrime-disclosures-scarce-despite-new-SEC-rule-3672224.php#page-1/>.

24. Lenhart, A., Purcell, K., Smith, A., & Zickuhr, K. Social media and young adults (2010). Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from <http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Social-Media-and-Young-Adults.aspx/>.

25. McAfee®. McAfee Threats Report: First quarter 2012. Retrieved from <http://www.mcafee.com/us/resources/reports/rp-quarterly-threat-q1-2012.pdf/>.

26. McAfee®. McAfee Threats Report: Third quarter 2012. Retrieved from <http://www.mcafee.com/us/resources/reports/rp-quarterly-threat-q3-2012.pdf/>.

27. Nakashima, E. & Warrick, J. (2012, June 4). Stuxnet was work of U.S. and Israeli experts, officials say. The Washington Post. Retrieved from <http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/stuxnet-was-work-of-us-and-israeli-experts-officials-say/2012/06/01/gJQAlnEy6U_story.html/>.

28. National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). State cyberstalking, cyberharassment and cyberbullying laws. Retrieved from <http://www.ncsl.org/IssuesResearch/TelecommunicationsInformationTechnology/CyberstalkingLaws/tabid/13495/Default.aspx/>.

29. National Gang Intelligence Center. (2009). National Gang Threat Assessment.

30. NYDailyNews.com. (2012, March 20). Online dating sites give boot to sex offenders. Retrieved from <http://articles.nydailynews.com/2012-03-20/news/31217130_1_spark-networks-sexual-battery-website/>.

31. Pinkston, R. (2011, August 10). British riots exposing social media’s dark side? CBS News. Retrieved from <http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2011/08/10/earlyshow/main20090575.shtml/>.

32. Poeter, D. (2012, September 24). New hacker collective emerges in response to anti-Islamic film. PC Magazine. Retrieved from <http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2410127,00.asp/>.

33. Reuters. (2012, October 11). ‘Shamoon’ virus most destructive ever to hit a business, Leon Panetta warns. Huffington Post. Retrieved from <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/10/11/shamoon-virus-leon-panetta_n_1960113.html/>.

34. Smith, J. History of HTCIA. Retrieved from <http://www.jcsmithinv.com/HTCIAhistory.htm/>.

35. Sulemanzp. (2011, November 11). Dugu virus attacked Iran’s defence network!. Info Rains. Retrieved from <http://inforains.com/dugu-virus-attacked-irans-defence-network/>.

36. Symantec. (2011). Norton™’s Cybercrime Report 2011. Retrieved from <http://www.symantec.com/content/en/us/home_homeoffice/html/ncr/>.

37. Tech Terms. <http://www.techterms.com/>.

38. Traynor, L. (2012, May 3). ‘Reservoir Dogs’ killer Allan Bentley accused of threatening female trial witness on Facebook while behind bars. Crosby Herald. Retrieved from <http://www.crosbyherald.co.uk/news/crosby-news/2012/05/03/reservoir-dogs-killer-allan-bentley-accused-of-threatening-female-trial-witness-on-facebook-while-behind-bars-68459-30888759/>.

39. Vaughan, A. (2011, June 18). Teenage flash mob robberies on the rise. Fox News. Retrieved from <http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/06/18/top-five-most-brazen-flash-mob-robberies/>.

40. Verizon. 2012 Data Breach Investigations Report. Retrieved from <http://www.verizonbusiness.com/resources/reports/rp_data-breach-investigations-report-2012_en_xg.pdf/>.

41. Wortham, J. (2009, February 3). MySpace turns over 90,000 names of registered sex offenders. New York Times. Retrieved from <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/04/technology/internet/04myspace.html>.

1Kevin Mitnick, a.k.a. Condor, was an infamous hacker of the 1990s. He gained notoriety after being wanted by federal authorities.

2From 1999 to 2006, the survey was known as the CSI/FBI survey. In 2007, the survey was renamed with the “FBI nomenclature” being discontinued and the survey being entirely administered by CSI. Source: CSI Survey 2007: The 12th Annual Computer Crime and Security Survey. Retrieved from http://gocsi.com/sites/default/files/uploads/2007_CSI_Survey_full-color_no%20marks.indd_pdf.

3Malware is short for “malicious software,” a term used to collectively refer to software programs designed to damage or do other unwanted actions on a computer system. Examples include viruses, worms, Trojan horses, and spyware (http://www.techterms.com).

4Internet crime is by no means solely a male activity. The vast majority of enticement cases involve male suspects. However, females have also been involved in this criminal conduct. Throughout this book we will use the male gender, unless we are discussing a real case in which a female was involved.

5Commencing on February 16, 2011, Norton started a “real-time” cybercrime index, purporting to reflect the newest attack. See http://us.norton.com/theme.jsp?themeid=protect_yourself.

6The 24 countries were Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Germany, Holland, Hong Kong, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and United States.

7Think of fishing in the lake, but instead of capturing fish, individuals are trying to steal personal information. They accomplish this by sending out emails, which appear to be from legitimate sources, such as your bank. The email purports that your information needs updated or your account needs validated and requests you to enter your user name and password, after clicking a link. In reality you are providing your identifiers to the phisher (http://www.techterms.com).

8Smishing is similar to phishing. However, instead of email the offender sends fraudulent messages over SMS (text messages). The term is therefore a combination of “SMS” and “phishing” (http://www.techterms.com).

9A malicious URL is frequently a fraudulent version of a legitimate website, which contains malware that will infect the unsuspecting user.

10A botnet is a group of computers controlled by an offender or group of offenders. A botnet can be a few hundred or several thousand computers. An offender's control of these computers is often unknown by the legitimate user. Frequently a botnet will be used to launch a denial of service attack (DNS) against a website. By directing all computers in a botnet to make requests of a website they can either overload it or make it impossible for legitimate users to get access. Botnets are also referred to as zoobie armies (http://www.techterms.com).

11Malware have been developed for Windows-based personal computers as they had the lion share of the market. This increasing targeting of Macintosh® computers by offenders is a recognition that their usage is becoming more common place.

12Ransonware infects a user's computer and extorts money from its victim. It often purports to be from a law enforcement agency, accusing the user of illegal activity, locking the computer, and demanding payment of a “fine” to unlock the device.

13A rootkit is probably the most serious of malware. It is designed to give the offender administrator level access to a computer without being detected. Once such access is gained the offender can perform all manner of criminal activity, from stealing or destroying data to using the computer to launch an attack against another system (http://www.techterms.com).

14Everyone is probably familiar with the story about the Trojan Horse and how some Greek soldiers hid inside the “gift” presented to the Trojans. In this manner, the Greeks were able to get inside the Trojan's fortifications and open the gates. A Trojan is malware hidden inside another program, such as a game or screen saver, that once executed does something the user did not wish to happen (http://www.techterms.com).

15Spam is electronic junk mail, named after Hormel's canned meat (http://www.techterms.com).

16Stuxnet and Dugu were reportedly malware developed to thwart and gather information about the Iranian nuclear program (Nakashima & Warrick, 2012; Sulemanzp, 2011). Shamoon was the malware that attacked Saudi Arabia's state oil company, ARAMCO, replacing crucial system files with an image of a burning US Flag (Reuters, 2012).

17Verizon is a company that designs, builds, and operates networks, information systems, and mobile technologies. Their risk team provides security products and services and gathers intelligence as part of that function. Source: http://www.verizonbusiness.com/Products/security/risk/.

18The law enforcement agencies were Australian Federal Police, Dutch National High Tech Crime Unit, Irish Reporting and Information Security Service, Police Central e-Crime Unit, and United States Secret Service.

19Initially the IC3 was called the Internet Fraud Complaint Center. It was renamed in October 2003 to better reflect the broad character of Internet crimes.

20Flash mobs were coordinated in the United Kingdom through posts on Twitter, usually via cell phones to meet at a specific location and to commence rioting and looting. Flash robs occurred in the United States, where a specific location, such as a store, was targeted for mass shoplifting, with the attack being coordinated through social media and cell phones.

21Usenet was at one time “the world’s biggest electronic discussion forum,” where individuals could post and response to comments and upload and download files. There was communication but it was not yet generally friendly to nontechies (Gralla, 1996).

22Trademark of Vere Software.