Internet Criminals

This chapter discusses various criminal profiles and data on Internet criminals.

Key Words

Cyberbullying; cybercrime profiling; cyberharassment; cyberhucksters; cyberpunks; cyberstalkers; cyber-thieves; cyberterrorism; cyberwarfare deductive profiles; inductive profiles; Internet Crime Complaint Center; Internet criminals; Internet harassment; MEECES; Nigerian scams

If ignorant both of your enemy and yourself, you are certain to be in peril.

(Sun Tzu, Chinese Philosopher and author of “The Art of War,” died 496 BC)

Chapter 1 introduced a working Internet crimes definition, specifically, offenses committed on or facilitated through the Internet’s use. The difficulty in determining Internet crimes’ true societal impact was also discussed. But what about the individuals that are committing these offenses? What do we know about them? Who exactly is the Internet criminal?

Conly (1989) was one of the first to provide an answer. She portrayed the typical computer criminal as 15–45 years old, usually male, and with an ability from highly skilled to someone with little or no technical experience. Additionally, the profile characterized these offenders as usually having no previous law enforcement contact, bright, motivated, and ready to accept technical challenges, who feared exposure, ridicule, and loss of community status. These offenders also appeared to deviate little from the accepted societal norms. They frequently justified criminal acts by viewing them as only a “game.” The majority of the cases were committed by one person, however, conspiracies were starting to surface. Both government and business systems were targeted. A significant number were also “insiders,” holding a trusted position in an entity, who had easy access to the victim’s systems. These insiders were the first to arrive and the last to leave the office, taking few or no vacations. This profile centered on the hackers and insiders, initially the only ones committing computer crimes.

Remember this profile was created over 20 years ago, before the existence of the graphical user interface (GUI), now present on all computers. Early cybercrimes required knowledge of command line functions and frequently computer code. This profile was also created well before the Internet’s massive growth or the emergence of social networking. It also predated cult hit movies like Sneakers (1992), Hackers (1995), and The Net (1995), which publicly exposed Internet crimes to the masses.

The unique and little understood technical skills in the 1980s are no longer needed today. Shortly after the 911 terrorist attacks, noted information security researcher and author,1 Denning (2001) observed “…the next generation of terrorists will grow up in a digital world, with ever more powerful and easy-to-use hacking tools at their disposal.” Now if one doesn’t know how to do a technical task, such as hacking, a useful video tutorial can frequently be found online. YouTube® hosts instructional videos on how to hack most anything, including social media accounts on sites like Facebook®, websites, and your home WiFi network. We are now living in an era where all manner of criminal behavior, including terrorism, can be easily learned and committed with an Internet nexus. This chapter will focus on more recent attempts to profile the Internet criminal so we can “know the enemy.”

Cybercrime profiling

Former FBI agent and profiler, William Tafoya2 defined “cybercrime profiling … as the investigation, analysis, assessment and reconstruction of data from a behavioral/psychological perspective extracted from computer systems, networks and the humans committing the crimes” (Radcliff, 2004). For our purposes the profile data is being extracted from the Internet, the largest network of all.

“Experts agree knowing more about the different skills, personality traits and methods of operation of computer criminals could help the folks pursuing these criminals” (Bednarz, 2004). There have been numerous cybercrime profiles developed over the years. Most early efforts focused on computer intrusions and hacking offenses. There are notable exceptions, such as those for cyberstalking and sexual exploitation offenders. Before delving into profile specifics it is important to understand that profiling comes in two varieties, the inductive and deductive approaches. The inductive approach assumes that individuals who committed the same crimes in the past share characteristics with individuals who are committing the same crime now. Examples of such profiles are those created for serial killers and rapists. The deductive approach uses evidence collected at the crime scene to develop a specific profile that can be used for offender identification. Understanding inductive profiles helps as the deductive approach frequently looks to them for clues in developing a more specific offender profile (Petherick, 2005).

Inductive profiles

As noted previously, much of the early inductive profiles focused mainly on the hacking and intrusions. Additionally, some efforts were not detailed but merely broad groupings. For instance, Kovacich and Jones (2006) indicated that early attempts placed hackers into the following three basic categories: the curious—hackers wanting to know more about computers; meddlers—hackers seeking the challenge of breaking in and finding system weaknesses; and criminals—hackers who commit these offenses for personal gain. Arkin, Kilger, and Stutzman (2004) further elaborated on the cybercriminal’s motivation by adapting the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s approach for examining espionage motivations for use with Internet criminals. Their acronym for these motivations was MEECES, which stands for Money, Entertainment, Ego, Cause, Entrance to social group, and Status.3

Cybercriminal profiles

Later attempts were much more defined and elaborate, further refining the skill level and motivations of each cybercriminal. One such hacker profile came up with eight cybercriminal subtypes (Bednarz, 2004). Shoemaker and Kennedy (2009) later developed an expanded cybercrime profile with the following 12 subtypes, again based upon skill level and motivation:

1. Kiddie (Script kiddie): This group is not technologically sophisticated and uses others’ preprogramed scripts or menu-based programs. Their motivation is ego driven, usually with the intent to trespass and sometimes to invade a user’s privacy. (This does not mean they are harmless as the preprogramed tools can make less sophisticated users very dangerous.)

2. Cyberpunks: This group is technologically proficient, usually young, counterculture members, and outsiders. Their motivation is also ego driven, focusing on trespass or invasion, the later of which motive is exposure. They will, however, engage in theft and sabotage but only on targets they view as legitimate. They are often responsible for many viruses, application layer, and denial of service (DOS) attacks against established companies and their products.

3. Old timers: Probably the most technologically proficient, this group’s motivation is ego driven and perfecting the cyber-trespassing “art.” They tend to be middle age or older, with an extensive personal and/or professional technology backgrounds, including hacking. They are the last of the “Old Guard,” whose purpose was to show how good they were at overcoming defenses to gain unauthorized entry into systems. This group sometimes engages in website defacement. As they frequently knew what they were doing they usually did not cause much harm. The notable exception is the heart burn to systems administrator who has to patch the security vulnerability and check their systems to make sure there were no additional “surprises” left behind by their intrusion.

4. Unhappy insider: This profile is considered the most dangerous as these individuals are inside an organization’s defenses. They can be any age and employed at any level. The major characteristic is they are unhappy with the organization and hence their motivation is revenge, oftentimes coupled with monetary gain. As a result their intent is to steal or harm the company. They may engage in extortion or exposure of company secrets. This group’s criminal acts are more dependent upon direct system access as opposed to secondary access via the Internet. However, they will use Internet access to obtain tools, transfer stolen goods to their possession, or to meet other objectives.

5. Ex-insider: This is the former employee that separated from the company unwillingly through layoff or unsatisfactory performance/conduct. Again, the motivation is revenge and the purpose is to harm the company. They may use insider information to discredit the company or to overcome vulnerabilities not publicly known. If termination is not well planned and they foresee it, they may plant logic bombs or perform other destructive acts to data and/or systems.

6. Cyber-thieves: This group can be any age and do not require vast technological experience. Their motivation is profit, either stealing data or outright monetary theft. They are adept at social engineering. However, they also will use network tools (sniffing or spoofing) as well as programing exploits to get what they want. They will oftentimes get employed by a company to work from the inside, making it easier to steal. Others will work their “magic” from the outside.

7. Cyberhucksters: These are the spammers and malware distributors. They are focused on monetary gain and commercialization. They are very good at social engineering as well as spoofing. They employ spyware, tracking cookies, and even legitimate business data mines to find victims for their “products.” One example of their handiwork is the pop-up banner that appears notifying the unsuspecting user that their system is infected and they need to buy the cyberhuckster’s anti-virus tool, the cure for the “infection.”

8. Con man: This group is motivated by monetary gain and theft is their trademark. They run the Nigerian scams but are not above phishing to commit identity and credit card theft. They are very good at social engineering and spoofing. They are harder to catch as they tend to be antonymous. Frequently, their attacks do not target specific victims, e.g., mass phishing attacks. However, some will engage in more targeted attacks on high value targets, sometimes referred to as “spear phishing.”

9. Cyberstalker: This group is driven by ego and deviance. They want to invade their victim’s privacy to satisfy some personal, psychological need like jealousy. Shoemaker and Kennedy (2009) also noted this group primarily uses such tools as key loggers, Trojan Horses, or sniffers. However, as will be discussed later, this group is far more resourceful and diverse.

10. Code warriors: They report that this group is one of the most skilled with long histories based in technology, oftentimes with degrees. Initially, their focus was on ego enhancement and sometimes revenge. However, they have since become capitalistic, engaging in theft or sabotage. Unlike the Old Timers, who viewed their activity as an “art” they tend to look at it as a profession. They are code exploiters and Trojan Horse creators. They can be any age, but usually fall in the 30–50 age group. Additionally, they are usually socially inept and social deviants.

11. Mafia soldier: This group has some of the characteristics of the con man and code warriors. They are highly organized with the criminal purpose of making money in whatever manner possible. They commonly engage in theft, extortion, and privacy invasion with the goal of blackmail. Many of this group are located in the Far East and Eastern Europe, although all organized crime will likely get into this lucrative illegal enterprise.

12. Warfighter: Unlike the other groups, this subtype is viewed only as cybercriminal if they are fighting against you. They can be any age, but are the best and brightest any country can muster. Their motivation is infowar and they are after strategic advantages for their country and its allies and harm to their enemies. They employ all cyberweapons at their disposal, including Trojan Horses, DOS attacks, and the use of disinformation.

The above would seem to be an exhaustive list of Internet criminal subtypes. Unfortunately, Shoemaker and Kennedy’s profiles neglect numerous areas of Internet criminality. For instance, none of the subtypes mention the various Internet auction frauds involving misrepresentation or nondelivery of products. They also do not cover click fraud, which involves fraudulently increasing Internet advertising revenue by manipulating the number of “clicks” generated from users accessing website ads (Grow, Elgin, & Herbst, 2006). The subtypes also do not cover Internet stock fraud, where individuals provide misleading or bogus information via the Internet to potential investors to get them to buy stock (US Securities and Exchange Commission, 2011). The ease of Internet fraud is best represented by a 16-year-old “pump and dump” scheme, in which he fraudulently hyped a stock online to drive up its value and then sold it, receiving $285,000 in ill-gotten gains (CBS News, 2009). It might be argued that these behaviors fit under one of the subtypes, such as cyberhuckster or con man. There is also no mention of such activities as illegal online gambling operations or illicit sale of pharmaceuticals. None of their subtypes match up neatly with these other cybercrime acts.

Shoemaker and Kennedy’s profile also does not delve into the Internet’s use by murderers. Detectives have known for years that some murders will use the Internet for research on methods to dispatch their victims. However, some murderers, more specifically serial killers, are using the Internet to hunt. Reportedly, the Internet’s first serial killer, John Edward Robinson, found his post 1993 victims by trolling online chatrooms (Wiltz & Godwin, 2004). There are numerous other cases of killers meeting and luring their victims to their deaths via Craigslist (Associated Press, 2009; Kaufman, 2012; NY1 News, 2011; Snow & Kessler, 2009). One of the most notable is the unsolved serial murder case known as the Long Island Serial Killer a.k.a. the Craigslist Ripper (Fernandez & Baker, 2011). There is even a case where a police officer has been accused of online planning and communication of his intent to kidnap, rape, torture, kill, cook, and cannibalize adult women (Serna, 2012). His planning, which was thankfully interrupted by his arrest, included a computer database of 100 women containing personal information and their physical descriptions (Serna, 2012).

Cybersex offenders

Another Internet criminality overlooked by Shoemaker and Kennedy’s profile is the cybersex offender. The US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (1999) identified three broad cybersex offender types: (1) the dabbler (the curious with access to child pornography), (2) the preferential offender (the deviant with sexual interests involving juveniles), and (3) the miscellaneous offender (pranksters or the misguided who come into possession of child porn as a result of their own investigations). However, these categories are more specific to offenses, involving possession, distribution, and manufacturing of child pornography.

In 2000, Detective James F. McLaughlin provided a more inclusive typology. He reviewed 200 sex offenders arrested as part of a 3-year Internet law enforcement project conducted by the Keene Police Department, New Hampshire. This project targeted preferential sex offenders. From his review, he identified the following four cybersex offender categories.

1. Collectors (n=143, 72%): McLaughlin considers this group made up of many “entry level” offenders, most of whom had no criminal record or had any known illegal contact with children. Collectors range in age from 13 to 65 years of age. The majority were single and living alone. Twenty-one percent were in vocations that involved contact with children. Specific occupations included: a college professor, a social worker, a camp director, an attorney, a youth counselor, school teachers, and law enforcement officers. McLaughlin observed that more individuals may be engaged in child pornography collection/trading, erroneously believing their online activities were anonymous and untraceable. He notes initially these offenders start their collection from static Internet locations (newsgroups and web pages), which do not involve real-time online interaction with other computer users. Eventually, most collectors escalate to dynamic Internet locations, involving real-time interaction with others, web-based chatrooms, and Internet relay chat. Once at the dynamic locations, these offenders also start distributing child pornography. The images in many ways become a deviant currency. Oftentimes, these offenders set up the specific file directories so they can retrieve images quickly for viewing and/or online interactions.

2. Travelers (n=48, 24%): This group is made up of offenders who engage in online chats with minors and use their manipulation skills and coercion to arrange for in-person meeting for sexual purposes. Offenders in this group were 17–56 years of age. Traveler occupations included military officer, attorney, athletic director, priest, college professor, high school teacher, and a civil engineer. A majority of these offenders also collected child pornography. Travelers do not always have any criminal sex offense history. These offenders would frequently travel great distances after only chatting online a few minutes. Four traveled internationally (Canada, Holland, and Norway) and the others traveled from 10 different states. Over 50% falsely claimed they were in their teens during their online communication, with some revising the claim to something more realistic, but still false. Over 50% also sent actual pictures of themselves, many of which were nudes. Grooming communication frequently involved the offender obtaining personal information, developing trust, engaging in sexual banter, and sending pornographic images. Many maintained that they would never coerce a minor into sexual behavior, noting their conduct would be mutual. At the scheduled meetings, these offenders would show up with condoms, lubricants, photo equipment, blankets, and even Viagra®. Some offenders would send funds or bus/airline tickets to the minor to facilitate them in running away. Three of these offenders were considered to be sadistic pedophiles.

3. Manufacturers (n=8, 4%): McLaughlin notes “…not all collectors are manufacturers but all manufacturers are collectors.” The age range for manufacturers was 26–53 years. Most manufacturers were sexually involved with children or to had criminal sex offense histories. Many of these offenders had photographed children they molested years ago, were actively molesting, or were in the grooming process. In at least 50% of the cases runaway children were found being harbored in the offender’s homes. Financial gain was not the motivation, with only one offender gaining less then $1,000.00. Manufacturer occupations included: professional nanny, photographer, airport worker, building superintendent, and youth music teacher.

4. Chatters (n=1, 0.05%): McLaughlin included this category which is clearly based upon more information than just this study. He indicated these offenders collect child erotica (nude images) as opposed to child pornography (images depicting sex acts or lewd exhibition of genitalia area). He notes these individuals refuse to send images over the Internet, do not trust others who send them images, and warn underage persons not to do so. They are daily online as much as 12 hours more. They consider and present themselves as “teachers.” Chatters will draw clear behavior lines in chatrooms, which they will not deviant from and expect others to honor. Nevertheless most will engage in cybersex and after rapport has been established escalate into phone sex. However, they are satisfied with this contact and will not want to meet the minor in the real world.

The idea that a cybersex offender’s conduct is merely fantasy is not something we support, particularly as some offenders use such reasoning to rationalize their criminal conduct. However, Young (2005) presents an interesting profile with two broad online sex offender types, virtual (situational) and classic. Her profile is based upon 22 forensic interviews with suspected online sex offenders. Young recognizes the illegal conduct is serious but notes that virtual offenders are involved as experimentation, fantasy, and/or as a novelty. For Young, the virtual sex offender’s online criminal behavior is more situational. They will have sexual relations with minors but juveniles are not their exclusive interest. Virtual online sex offenders start out as adult fantasy. For instance, they may begin in a chatroom called Married/Flirting and move to more suggestive rooms, such as Father/Daughter or OlderMen/Virgins. Their chat dialog is usually quick, explicit, and with little trust building or grooming. They are generally truthful about their age, name, and intentions. These offenders also tend to show remorse or shame after they are caught. The chronic online sex offender focuses on minors and has in exclusive sexual interest in juveniles. They start with teen chatrooms or other areas where minors frequent. They will go into other chatrooms, such as Father/Daughter, to trade child pornography but they realize these areas are frequented by adults pretending to be minors. Their chats are disguised, subtle, and consistent with a traditional molester’s grooming techniques. They will lie about their identity as well as their true intentions. They express little or no remorse or shame at getting caught. For Young (2005), classic offenders “…exhibit a chronic and persistent pattern of sexualized behavior toward children” and as a result they “…are clearly a more serious threat to the welfare of children as they utilize the Internet, because they often have prior convictions related to sexual crimes against children on their records.”

Internet harassment

Shoemaker and Kennedy subtypes frequently rely too much on software techniques by the offender, such as key loggers, Trojan Horses, or sniffers by cyberstalkers. It is true that those tools are used in some cyberstalking cases, but those high-tech tools are not present in all cases. Additionally, their subtype fails to note that cyberstalking can involve Internet communication, such as posting to a website, or the Internet as a research tool, such as on the victim or for techniques/tools. This criminality, along with cyberharassment and cyberbullying are collectively referred to as Internet harassment (Smith, 2008). These acts are defined as follows:

• Cyberstalking is the repeated use of the Internet, email, or related digital electronic communications devices to annoy, alarm, or threaten a specific individual or group of individuals (D’Ovidio & Doyle, 2003, p. 10).

• Cyberharassment involves electronic communications (e.g., email, Internet, social networking sites), absent a specific threat to the victim, e.g., continued posting unwanted, off topic, and/or unflattering comments on a social networking site, in a blog, or in a chatroom (Bowker, 2012).

• Cyberbullying is cyberharassment when both the victim and the offender are juveniles. It encompasses not only harassment activities but veiled threats (Bowker, 2012).

McFarlane and Bocij (2003) developed a useful cyberstalking topology based upon their interviews with 24 victims located in numerous countries, including Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Their topology has the following four groups:

1. Vindictive cyberstalker: These groups threaten their victims more than the others and in the majority of cases also included offline behavior. One-third of this group had previous criminal records and two-thirds were known to have previously victimized others. Their computer literacy was rated medium to high by their victims. This group, more than any other, utilized the widest range of Internet tools, such as spamming, mailbombing, and identity theft, to harass their victims. This group was also the only to use Trojan programs. Three-quarters of this group’s victims reported receiving bizarre or unclear/unrelated comments and intimidating multimedia images and/or audio files, e.g., skull and crossbones, corpses, screams, etc. In these instances such comments were taken as evidence these stalkers had severe mental issues. Two-thirds of these victims had known their stalker before the victimization commenced. Half of the victims noted the harassment started over some trivial matter and was blown out of all proportion. One-third of the victims saw no apparent reason for the stalking. The rest of the victims acknowledged they had previously been in an active argument with their stalker.

2. Composed cyberstalker: This group was made up of stalkers who were not trying to establish any relationship with their victim. Their only apparent goal was to cause distress by constant annoyance and irritation to their victims. This group also was estimated to have a medium to high level of computer skills. These stalkers issued generalized threats to their victims. Only one in this group had a record and only one had any previous stalking history. None in this stalker group had any psychiatric history. Nevertheless, three went on to stalk their victims offline.

3. Intimate cyberstalker: This group was actually made up of two subgroups, ex-intimates and infatuates. Ex-intimates were a victim’s ex-partner or ex-acquaintance. Infatuates were individuals looking for an intimate relationship with their victim. This group was characterized as trying to gain attention and/or obtain a relationship with the victim. Additionally, victims reported this group having a wider range of computer skills than other groups, from fairly low to high. These stalkers utilized email, web discussion groups, and electronic dating sites and demonstrated detailed knowledge about their victims. The ex-intimate subgroup engaged in online behaviors ranging from trying to restore their relationship with the victim to threats on the victim’s significant other or friend. In some cases the ex-intimate impersonated their victim, such as pretending to be their ex-partner in chatrooms or buying goods online in their name. Surprising that in this subgroup there were no cases of offline stalking occurring after the cyberstalking. Infatuates were seeking to form a closer relationship with their victim, often through more intimate communication than the other subgroup. However, when their attempts were rebuffed their messages became more threatening. In one infatuate case, the offender stalked the victim offline.

4. Collective cyberstalkers: This last group involved two or more individuals stalking their victim online. This group’s stalkers envisioned themselves wronged by the victim and accordingly sought to punish the victim. At times this group would recruit others to harass the victim offline. Victims ranked their stalker’s computer literacy from fairly high to high. Online stalking behavior included threats, spamming, email bombing, identity theft, and intimidating multimedia to harass the victim. This group also did research on their victims. Additionally, McFarlane and Bocij realized another subgroup, corporate cyberstalking, might exist. In such cases, an organization might be criticized for a business practice and take offense. In turn, they would use harassment to discredit and/or silence the victim. This group also used identity theft to impersonate and discredit victims.

Cyberterrorism and cyberwarfare

Although Shoemaker and Kennedy’s Warfighter subtype discusses acts of cyberwarfare, their profile really does not adequately address cyberterrorism. We previously mentioned the general motivation of the criminals committing crime, including the MEECES approach. The motivations for persons committing crimes on the Internet are very different than those whose intent is to commit an act of terrorism or a cyber-act of warfare. The players are also very different with varying funding and technical skill levels.

A cyberterrorists motivation is political in nature. The effect of their actions is most likely “mass disruption” as described by Rattray (2001). The intention of the cyberterrorist is not to necessarily kill anyone, but to cause disruption of services. An attack on any critical infrastructure controlled through technology can cause significant disruption to a community and force a hysterical reaction by its citizens. The cyberterrorist most likely is from an organized group but may not have extensive forethought in its application of the act.

Nelson, Choi, Iacobucci, Mitchell, and Gagnon (1999) looked at the five terrorist group types (religious, New Age, ethnonationalist separatist, revolutionary, and far-right extremist) and made some interesting conclusions in their pre-911 world. They noted that religious groups were “…likely to seek the most damaging capability level; as it is consistent with the indiscriminate application of violence that has distinguished much of their activity” (p. 10). At the time they thought the most immediate threat was the New Age or single-issue terrorist community (e.g., Animal Liberation Front), as such groups were more willing to accept disruption as a destruction substitute. They noted both Religious and New Age groups and their primary targets were located in areas with numerous high-tech targets. Additionally, both groups had the best match among desire, ideology, and environment to facilitate an advanced cyberattack. They concluded both the revolutionary and ethnonationalist separatist (ENS) groups were likely to desire the ability to launch an advanced cyberattack, but for differing reasons. For them, an advanced cyberattack offered the revolutionary group the necessary degree of control over the unintended consequences that might occur with an indiscriminate cyberattack. For the ENS group, an advanced cyberattack could serve to supplement a traditional terrorist act. Nelson et al. (1999) concluded far-right extremists were not likely to seek the advanced cyberattack capability, noting in part it was not consistent with a far-right terror psychology. Additionally, far-right groups used computer networks more often for their operations and any widespread disruption would likely also negatively affect them.

Cyberwarfare differs from cyberterrorism as it is an organized effort by a nation state to conduct operations in cyberspace against foreign nations. Included in this category is the Internet’s use for intelligence gathering purposes. Cyberwar has become the little understood adjunct to cyberspace that has the potential for the greatest impact to the Internet. An all-out assault by nation states against each other would leave private citizens in its wake. The nations with the most integration of technology in their citizen’s lives have the most at stake. Although emerging nations developing a technology infrastructure with a growing dependency on cellular technology could be the first to fall in any concerted broad-based cyberattack. Totalitarian regimes have found that the simple act of restricting “Tweets” can have a great effect of controlling the masses or disrupting organized activities. Interrupting the communication flow through social media could isolate a country and mask further aggressive acts. A modern example of cyberwar can be found in the alleged acts of the Russian government against their former states Estonia and Georgia (Ashmore, 2009). The Russian government allegedly used cyberattack strategies in an attempt to cripple the countries because of alleged grievances against Russia.

We will next examine some recent historical data on Internet criminals, which will hopefully provide further clues that will aid in classification and identification.

Internet Crime Compliant Center

From 2001 to 2010, the Internet Crime Compliant Center (IC3) regularly reported some characterizations of the Internet criminal. The characteristics were limited to offender gender, location, and in some reports, the method of contacting the victim. The reasons for dropping this information from the 2011 report are unknown. There is a caveat in the 2009 year report cautioning readers that information pertaining to “…perpetrator demographics represent information provided to the victim by the perpetrator so actual perpetrator statistics may vary greatly” (p. 7). Additionally, the 2009 report reflects that perpetrator gender and their residence state were reported only 38.0% and 35.1% of the time, respectively. The 2010 IC3 report, which was the last year perpetrator information was provided, reflected that nearly 75% the online crimes were committed by men. More than half resided in California, Florida, New York, Texas, the District of Columbia, or Washington. The United States accounted for 65% of the overall reported perpetrators (if known) of online crime. The United Kingdom was next with 10.4% and Nigeria in third at 5.8%. Prior IC3 reports occasionally reported the majority of perpetrators were in contact with their victim through either email or via websites.

It is understandable that the IC3 may have decided that providing perpetrator demographics was problematic. After all, the nature of these crimes is such that the perpetrator can portray themselves to be anyone, located anywhere but where they really are located. There are anonymization (or hiding) methods that will be discussed later that offenders use on the Internet to prevent being caught. As such, it may be that IC3 concluded this information was of limited value.

One observation is noted though. For the 9 years this information was provided and it was pretty consistent. Males were reported as the perpetrator anywhere from 75% to 76%. Additionally, over half of all perpetrators were reported as living in one following states: California, Florida, New York, or Texas. Other states would appear and fall from the list but these states consistently were represented as the Internet criminal’s reported location. Additionally, the United States had the dubious distinction of being the vast majority of perpetrators’ home locations. Again, this is coming from complainant data and the perpetrator could be using some anonymization method to prevent being caught. But one does have to wonder why this data is consistent for each year, with no real changes. It seems unlikely that there is a grand Internet conspiracy by female criminals to make themselves male and appear to be located in the United States, in one of four particular states.

New York Police cyberstalking study

D’Ovidio and Doyle (2003) examined data gathered from all closed cases investigated by the New York Police Department’s the Computer Investigation & Technology Unit (CITU) from January 1996 to August 2000, which involved aggravated harassment. They found 201 (42.8%) of these cases involved a computer or the Internet as the instrument of the offense. Of these cases, 192 were closed during the study’s time frame. Case outcomes for these 192 cases revealed approximately 40% were closed with an arrest. Another 11% were closed due to insufficient evidence that a crime had occurred. The remaining cases were closed due to a jurisdictional issue, an uncooperative complaint, case transfer, or failure to identify a suspect. They then focused on the 134 cases where an arrest was made or in which a suspect was identified but not charged. They found that 80% of these cases involved males. The racial make-up of these cases was 74% white, 13% Asian, 8% Hispanic, and 5% black. The average offender age was 24 with the oldest being 53 and youngest being 10. They also found that females (52%) were more likely to be recipients of a threatening or alarming message. Thirty-five percent of the victims in aggravated harassment cases were males. Educational institutions were targeted in 8% of the cases. Private corporations and public sector agencies were targeted in 5 and 1% of the cases, respectively. The victim’s racial make-up was 85% white, 6% Asian, 5% black, and 4% Hispanic. The victim’s average age was 32 with the youngest victim being 10 and the oldest 62.

D’Ovidio and Doyle (2003) also found that in 92% of the cases the offender only used one cyberstalking method, which was most often email. They noted that 79% of the victims were harassed through email. The second most prevalent method was instant messaging, which was used in 13% of the cases. Chatrooms were used in approximately 8% of the cases. Message boards and websites were used in 4% and 2% of the cases, respectively. Remember that this data covered a period before social networking sites exploded on the Internet. Offenders employed newsgroups and false user profiles in only 1% of the cases. Offenders used anonymous remailers in only 2.1% of the cases. The majority of the cases involved investigations where both the offender and victim resided within the New York Police Department’s jurisdiction.

McFarlane and Bocij (2003) study involved a much smaller victim set, 24, but found many of the same trends. Twenty-two (92%) of the victims were female. The most common cyberstalking method was email. In 54% of the cases, offline stalking also occurred, with six victims stalked at home, three at their worksite, and three in public places. Additionally, one victim reported they were subject to surveillance by their offender. In 33% of the cases, the offender impersonated the victim online.

Sex offenders online activities

Dowdell, Burgess, and Flores (2011) completed a study in which students as well as convicted sex offenders were given a questionnaire regarding their online activities centering on social networking sites. The study’s time frame was from 2008 to 2009. Data was obtained from 466 convicted sex offenders, of which 113 were Internet sex offenders, which were defined as involving child pornography and/or travelers. The remaining 354 non-Internet sex offenders were child molestation (n=236), rapist (n=35), miscellaneous sex offenses (n=27) (not child molestation or rape; mostly indecent exposure or voyeurism), and generic offenses (n=55, no known offenses against children). Sixty child molesters also were Internet sex offenders.

They found that approximately 29% of the Internet offenders and 13% of the child molesters visited teen chatrooms. Approximately 29% of the Internet sex offenders entered chatrooms where they honestly identified themselves. Fifty-nine percent disguised their identity by name or age. Approximately 12% varied their truthfulness, sometimes being honest and sometimes lying about their identity. Roughly 63% of the child molesters provided truthful identity information in chatrooms. Approximately 37% disguised themselves, usually misstating their age. Those offenders who were both Internet sex offenders and child molesters were equally divided, 49%, between being truthful and lying concerning their identity. All offender groups preferred chatting with teenage girls. Sex offenders also preferred using MySpace® but students preferred Facebook®.

Approximately 63% of the Internet sex offenders reported initiated the topic of sex in their first online chat session. Twenty percent did so in sessions 2–6. Approximately 17% took 7 or more sessions to first approach the topic of sex. Approximately 7% of the incarcerated sex offenders and 10% of the sex offenders in the community reported having experience with an online avatar on SecondLife.4 In comparison, approximately 6% of high school students and 4% of college students reported having a SecondLife avatar.

Capability

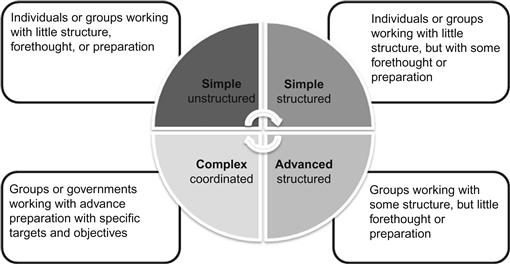

Clearly, the average Internet criminal is not necessarily a technology genius or the typical hacker. Today’s Internet creates a situational environment where anyone with access can become the next Internet criminal. Also, the availability of highly complex tools lowers the entry level for some criminals. As a result we need to take a broader approach to classify or more importantly identify the Internet criminal. Nelson et al. (1999) initially recognized three cyberterror capability levels, simple unstructured, advanced structured, and complex coordinated. Modifying these levels, with an additional fourth level, simple structured can be useful in discussing the Internet criminal. Simple unstructured involves individuals working with little structure, forethought, or preparation. Simple structured are individuals or groups working with little structure, but with some forethought or preparation. Advanced structured groups work with some structure, but little forethought or preparation. Complex coordinated are groups or in some cases governments, working with advance preparation with specific targets and objectives. These categories help us to understand the motivations and the resources of the individual criminals. The sophistication level and the potential for larger damages increase as the perpetrator becomes more organized. Everyone, including the reader of this text starts out with a minimal level of knowledge and skill. With education we have grown in our expertise and skill. As Internet offenders educate themselves and become more active in their pursuit of criminal activity they increase their potential for harm. Additionally, if they associate with others, either loosely or through an organized structure, the level of their potential for damage exponentially expands (Figure 2.1).

At the lowest level within the simple unstructured category exists a large percentage of the cybercriminal element. This is the breeding ground for far more sophisticated action by the more organized groups. These individuals work with little structure. They are not organized for any real criminal effort and their general actions are done with very little in the way of forethought or preparation. Examples of this are the typical novice in the hacking arena. They are new to most aspects of the cyber world and spend much of their time learning about hacker techniques and tactics. In doing so they are likely to exceed their authority on a network, most likely one they are given access to as an employee. They may explore their office network and spy on others in the office. Obviously a properly configured network would not allow this and a trained network administrator with an active defense, internally and externally should identify the intruder.

The individuals identified as belonging to the simple structured category are individuals or groups working with little structure, but with some forethought or preparation. These include traditional hackers, disgruntled employees, and individuals committing crimes on the Internet. These also include the loose nit or cyber only affiliated hacking groups that associate with each other for the benefit of their egos versus the actual organized effort to hack into any company or government computer. Employees that are not happy with their current situation and plot damage or theft of company material requiring some planning and preparation are also categorized here. The online stalker (and we use this in the broadest sense here to include stalking of adults or children) is using little structure and is not an organized crime, but one that is thought out and planned.

The more complicated online threats come from the more advanced and complicated organizations. The advanced structured threat is an organized group working with some structure, but little forethought or preparation. These threats include the organized hacking group that has documented affiliations amongst its membership and generally similar philosophies that drive the group’s efforts. The hacking attempts or intrusions are generally not organized, although they may individually be sophisticated in their attack. The group’s individuals determine the effort more on a decentralized basis then in an organized planning from a single authority.

The most significant threat amongst all the categories comes from those threats that are both complex and coordinated. These groups or governments work with advance preparation with specific targets and objectives. This makes them the single most dangerous threat that a network has. For the investigator of Internet crimes this makes it the most difficult to investigate. The organized group or government can be involved in terrorist activity, committing acts of cyberwarfare, or collecting intelligence to support those activities. These are the most difficult to track down due to their extensive understanding of the technology and how to manipulate it to remain hidden from investigators.

As the investigator begins looking into an online crime or incident he or she frequently has no idea which perpetrator category they are investigating. A simple online fraud crime could be a front for terrorist funding, or a simple intrusion or website defacing could be a complex intrusion by a nation state to collect intelligence on a targeted company. It could also be that the website defacing is just a script kiddie trying a new piece of crimeware he found online. Ultimately each and every case will have evidence to collect and a perpetrator somewhere in the world. Internet crime victims experience harm just like any traditional crime victims suffer. Investigators have a responsibility to victims and society to follow the evidence where it leads. Some investigations may lead to nowhere and some to a successful conclusion. To cut short the investigative efforts solely on the basis of act being an Internet crime do not serve societal or justice interests.

Deductive profiling

Shoemaker and Kennedy (2009) observed that cybercrime profiling investigations involve five processes: evidence gathering, behavior analysis, victimology, crime pattern analysis, and profile development. Evidence gathering focuses on collecting all potential evidence, such as might be present in computer/network logs, on defaced websites, on social media sites, or forensically from a computer hard drive. Behavior analysis is the process of trying to obtain meaningful behavior characteristics from the evidence found. Victimology is the process of studying the victim for clues why they may have been targeted or for some kind of relationship they may have with the offender. Crime pattern analysis involves looking at the information and data from the first three stages in relationship to time and geography, and developing a working theory of who the offender might be, along with why the crime was committed. The last process, profile development, attempts to take the information and theories and create an offender profile. Frequently, this last process will look at other known profile groups, developed via the inductive approach, to bring into focus a specific offender profile. As the above reflects a knowledge of both the inductive and deductive approaches is extremely helpful in developing a useful profile that identifies the Internet criminal.

Additionally, we believe there are three general principles that pertain to identifying the Internet criminal, particularly when the offender and victim have no apparent relationship. The first principle holds that as the interaction between the offender and their victim increases, so does the potential to locate and identify the offender. The more times the offender sends an email, posts a message on a website or social networking site, etc. the more likely clues will be left behind for the investigator. Even offenders using anonymization methods, sometimes get comfortable, lazy, and make contact without adequately covering their tracks. Additionally, these clues are also not always in the form of digital evidence. An offender may inadvertently provide some piece of information, such as in an email, instant message, that gives away their identity. Take the case of cyberstalker using a bogus email or profile to communicate with their victim. As the communications continue, some will get caught in the moment and response something like “Don’t you know who this is? It is Tom from work.”

The second principle is as the Internet criminal creates more victims, the greater likelihood a pattern will be detected that leads to their identity. This is why it is so important that victims report the crime to law enforcement and is part of the reasoning behind the IC3 creation. As with the first principle, the Internet criminal may leave little or no evidence behind with the first few victims but get sloppy on the sixth or seventh victim and leave clues behind that lead to their location and identity. Additionally, as the Internet criminal increases their loss total with multiple victims, they increase the investigative attention. Few police agencies will devote much investigative resources to locating an Internet criminal who stole $100 from one victim. But an Internet criminal who steals $100 from say 1,000 victims, particularly if many are customers from the same financial institution, will likely result in an investigative response. As the victim tally increases, as well as the loss, so will the investigative resources devoted to finding the perpetrator(s).

The final principle is the more informed the victim, the better likelihood they will be able to assist the investigator. In cyberstalking cases, it is very important that the victim keep records of what happened when, as well as maintaining emails, instant messages, etc. By maintaining and providing this information to the investigator they can greatly assist in identifying the perpetrator. Additionally, from an online safety perspective, the more informed individuals are about the various Internet crimes, the greater likelihood they will not become victims in the first place. Obviously, this is an excellent law enforcement rationale for developing Internet safety presentations for their communities. Having an online safety initiative is less costly than conducting Internet crime investigations.

Conclusion

This chapter has introduced the wide diversity and variety of online criminal behaviors. All Internet crimes are clearly not all the same. Differences appear not only among the acts themselves but also the motivations and technical skills in each high-tech crime typology. Exposure to these differences helps investigators understand the reasons or motivations behind why individuals commit Internet crimes and will hopefully aid in offender identification. We also provided a simplified model for understanding these motivations. This model will assist to further understand Internet criminals and allow investigators better opportunities to identify and find those criminals.

Further reading

1. Arkin O, Kilger M, Stutzman J. Profiling. Know your enemy: Learning about security threats Boston: Honeynet Project: Addison-Wesley Professional; 2004.

2. Ashmore, W. (2009). Impact of alleged Russian cyber attacks a monograph. Retrieved from <http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a504991.pdf/>.

3. Associated Press. (2009, April 3). “Craigslist killer” Michael John Anderson gets life in murder of Katherine Olson. New York Daily News. Retrieved from <http://www.nydailynews.com/news/world/craigslist-killer-michael-john-anderson-life-murder-katherine-olson-article-1.361506/>.

4. Bednarz, A. (2004, November 29). Profiling cybercriminals: A promising but immature science. Network World. Retrieved from <http://www.networkworld.com/supp/2004/cybercrime/112904profile.html/>.

5. Bowker, A. (2012). A victim-centered approach to supervising internet harassment offenders. Perspectives special victim issue (pp. 92–99). American Probation and Parole Association. Retrieved from <http://www.appa-net.org/eweb/docs/appa/pubs/Perspectives_2012_Spotlight.pdf/>.

6. CBS News. (2009, February 11). Pump and dump. CBS News. Retrieved from <http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-18560_162-242489.html/>.

7. Conly C. Organizing for computer crime investigation and prosecution US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice 1989; Retrieved from <https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/118216NCJRS.pdf/>.

8. Denning, D. (2001). Is cyber terror next? Retrieved from <http://essays.ssrc.org/sept11/essays/denning.htm/>.

9. D’Ovidio R, Doyle J. A study on cyberstalking: Understanding investigative hurdles. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 2003;72 Retrieved from <http://www2.fbi.gov/publications/leb/2003/mar03leb.pdf/>.

10. Dowdell E, Burgess A, Flores R. Online social networking patterns among adolescents, young adults, and sexual offenders. American Journal of Nursing. 2011;111(7):28–36.

11. Fernandez, M., & Baker, A. (2011). Long Island Serial Killer gets a personality profile. The New York Times. Retrieved from <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/22/nyregion/long-island-serial-killer-gets-a-personality-profile.html?_r=0/>.

12. Grow, B., Elgin, B., & Herbst, M.. (n.d.). Click fraud. Retrieved from <http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2006-10-01/click-fraud/>.

13. Internet Crime Center (IC3). IC3 Internet crime report (2001 to 2011). Retrieved from <http://www.ic3.gov/media/annualreports.aspx/>.

14. Internet Crime Center (IC3). IC3 2010 Internet crime report. Retrieved from <http://www.ic3.gov/media/annualreport/2010_ic3report.pdf/>.

15. Kaufman, T. (2012, October 30). Jury finds stow teen Brogan Rafferty guilty on all murder charges in Craigslist killings case. News Channel 5. Retrieved from <http://www.newsnet5.com/dpp/news/local_news/akron_canton_news/jurors-reach-verdict-in-craigslist-killings-trial-of-stow-teen-brogan-rafferty#ixzz2B1×6uSIr/>.

16. Kovacich GL, Jones A. High-technology crime investigator’s handbook: Establishing and managing a high-technology crime prevention program 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier; 2006.

17. Lacy, S. (2012, July 6). Philip Rosedale: The media is wrong, SecondLife didn’t fail. PandoDaily. Retrieved from <http://pandodaily.com/2012/07/06/philip-rosedale-the-media-is-wrong-secondlife-didnt-fail/>.

18. Lasker, L., & Parkes, W. (Producers). (1992). Sneakers [Film]. Universal City: Universal Studios.

19. McFarlane, L., & Bocij, P. (n.d.). An exploration of predatory behaviour in cyberspace: Towards a typology of cyberstalkers. First Monday. Retrieved from <http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1076/996/>.

20. McLaughlin, J. (n.d.). Cyber child sex offender typology. Retrieved from <http://www.ci.keene.nh.us/police/Typology.html/>.

21. Nelson B, Choi R, Iacobucci M, Mitchell M, Gagnon G. Cyberterror: Prospects and implications Monterrey: Center for the Study of Terrorism and Irregular Warfare, Naval Postgraduate School; 1999; Retrieved from <http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA393147/>.

22. NY1 News. (2011, November 15). Teen convicted of fatally stabbing Brooklyn Radio Reporter. Retrieved from <http://brooklyn.ny1.com/content/top_stories/150835/teen-convicted-of-fatally-stabbing-brooklyn-radio-reporter/>.

23. Petherick W. The science of criminal profiling New York: Barnes & Noble Books; 2005.

24. Peyser, M. (Producer) (1995). Hackers [Film]. Los Angeles: United Artists Corporation.

25. Radcliff, D. (Profiling Defined) (2004, March 1). Network World. Retrieved from <http://www.networkworld.com/research/2004/0301hackersdef.html/>.

26. Rattray G. The cyberterrorism threat. In: Smith J, Thomas W, eds. The terrorism threat and US government responses: Operational and organizational factors. Colorado: USAF Institute for National Security Studies, US Air Force Academy; 2001; Retrieved from <http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usafa/terrorism_book.pdf/>.

27. Serna, J. (2012, October 12). New York Police officer arrested in plot to kidnap, cook, eat 100 women. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from <http://www.latimes.com/news/nation/nationnow/la-na-nn-police-officer-cannibal-women-20121025,0,6041707.story/>.

28. Shoemaker D, Kennedy D. Criminal profiling and cyber-criminal investigations. In: Schmalleger F, Pittaro M, eds. Crimes of the Internet. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009;456–476.

29. Smith A. Protection of children online: Federal and state laws addressing cyberstalking, cyberharassment, and cyberbullying. Congressional Research Service 2008; Retrieved from <http://ipmall.info/hosted_resources/crs/RL34651_091019.pdf/>.

30. Snow, M., & Kessler, J. (2009, April 21). Med student held without bail in possible craigslist killing. CNN. Retrieved from <http://www.cnn.com/2009/CRIME/04/21/mass.killing.craigslist/index.html/>.

31. Tzu, S. Retrieved from <http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/s/suntzu384543.html/>.

32. US Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Use of computers in the sexual exploitation of children. 1999; Retrieved from http://www.sec.gov/investor/pubs/cyberfraud.htm/>.

33. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission “Internet Fraud” (2011) Retrieved from <http://www.sec.gov/investor/pubs/cyberfraud.htm>.

34. Wiltz S, Godwin GM. Slave master New York, NY: Kensington Pub. Corp; 2004.

35. Winkler, I., & Cowan, R. (Producers). (1995). The Net [Film]. Los Angeles: Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

36. Young K. Profiling online sex offenders, cyber-predators, and pedophiles. Journal of Behavioral Profiling. 2005;5(1):18.

1Denning is an accomplished author of numerous books and articles on information security and is a distinguished professor with the Department of Defense Analysis, Naval Postgraduate School. Source: http://faculty.nps.edu/dedennin/.

2Tafoya was an FBI special agent who worked in both the FBI Academy's Computer Crimes and the Behavioral Science Units. He served as the lead behavioral scientist on the infamous Unabomber case. His 1993 bomber profile turned out to be an uncanny match of Theodore Kaczynski, who was later arrested and convicted. Tafoya's work was also instrumental in the founding of the Society of Police Futurists International (PFI). Tafoya is now professor and director of Research at the University of New Haven. Sources: http://www.copacommission.org/meetings/hearing3/tafoya.pdf and http://www.newhaven.edu/news-events/news-releases/88175/.

3The FBI's origin motivations for individuals who commit espionage against their country were Money, Ideology, Compromise, and Ego, which had an acronym of MICE.

4SecondLife is an online virtual reality, where users can create three-dimensional identities for themselves. These avatars can then work and play in a virtual community created by the user. In 2012, it was reported there were 1 million active users on SecondLife. Additionally, over $700 million a year in virtual goods transacted inside of SecondLife every year (Lacy, 2012).