Collecting Legally Defensible Online Evidence

This chapter discusses online or Internet evidence, which is electronically stored information (ESI) that has been properly collected, preserved, and for which a foundation has been laid for its admittance and/or consideration into a legal forum. The chapter’s focus is to provide investigators with the knowledge to gather the “best ESI,” so they can ensure their legal authority has a good basis to argue that it should be admitted into evidence. The legal concepts of relevancy, authentication, and hearsay are discussed as they relate to ESI. These concepts and other legal issues, including privacy, are presented from numerous International perspectives, including Canada, China, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Finally, investigative planning and the three basic steps of gathering online evidence (collection, preservation, and presentation) are discussed.

Key words

Electronically stored information; digital evidence; online evidence; relevancy; authentication; hearsay; chain of custody; collection; preservation; presentation; Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986; European Union Privacy Directive; Fair Credit Reporting Act; mutual legal assistance

Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.

(John Adams, American President, 1735–1826)

Chapter 3 focused on how the Internet works and the basics of navigating its recesses for information. Investigating Internet crimes, however, requires more than just the ability or knowledge to know where to look for information. Information or more specifically evidence must not only be located but also be collected and preserved in a manner consistent with getting it admitted into the appropriate legal venue. To do otherwise negates all the investigative effort in locating it and may create a legal “house of cards,” particularly if the discovered evidence was a particular case’s foundation. In Nardone v. United States 308 U.S. 338, 341 (1939),1 Justice Felix Frankfurter used the phrase “fruit of the poisonous tree” to describe the situation when a substantial portion of a case is built on evidence that was improperly obtained. US courts in such cases have held convictions cannot be sustained. Other countries have their own legal requirements for admitting information into evidence. As such we must be diligent that evidence found on the Internet is properly collected and preserved. This chapter will review the methods for insuring investigators do not gather Internet fruit from poisonous trees.

A few caveats are in order before we begin this review. We are not attorneys and do not play ones on television. We are not providing legal advice. We are simply providing information that will alert investigators to issues so they can plan accordingly. We strongly encourage investigators to obtain legal advice to insure collected data can be entered into evidence in whatever legal venue (administrative, civil, criminal, etc.) and jurisdiction is appropriate.

Defining evidence

There is a bit of confusion when we talk about the term “evidence.” We believe it can take many forms, which appears to evolve with each passing technological advance. DNA evidence was unheard of until relatively recently. The terms digital or electronic evidence are also relatively new, and the terms Internet or online evidence are even more recent. But these terms reflect nothing but the form of information, not whether it can actually be admitted into evidence. Consider the following definition:

ESI (Electronically Stored Information). Any information created, stored, or utilized with digital technology. Examples include, but are not limited to, word-processing files, email and text messages (including attachments); voicemail; information accessed via the Internet, including social networking sites; information stored on cell phones; information stored on computers, computer systems, thumb drives, flash drives, CDs, tapes, and other digital media.

(Department of Justice (DOJ) and Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO) Joint Working Group on Electronic Technology in the Criminal Justice System (JETWG), 2012, p. 12)

In the above United States definition it does not use the term “evidence.” Insa (2007) likewise noted in a European study2 that “None of the studied countries stipulate in their legal codes a specific definition of what electronic evidence is. In all of them researchers have come across some references that are more or less specific for traditional evidence, encompassing some of those pertaining to electronic evidence” (p. 286). Hura (2011), however, references that China’s new rules in criminal trials specifically address electronic evidence as follows:

Article 29: In examining electronic evidence, such as electronic mail, electronic data exchange, online chat transcripts, blogs, mobile telephone text messages, or electronic signatures or domain names, emphasis shall be placed on the following:

1. whether the electronic evidence stored on a storage medium such as a computer disk or CD has been submitted together with printed version;

2. whether the time, place, target, producer, production process, equipment for electronic evidence is clearly stated;

3. whether production, storage, transfer, access, collection, and presentation (of the electronic evidence) were carried out legally and whether individuals obtaining, producing, possessing, and witnessing the evidence affixed their signature or chop;

4. whether the content is authentic or whether it has undergone cutting, combination, tampering, or augmentation or other fabrication or alteration;

5. whether the electronic evidence is relevant to the facts of the case.

If there are questions about electronic evidence, an expert evaluation should be conducted. The authenticity and relevance of electronic evidence should be examined in consideration of other case evidence (p. 760).

The commonality of these different jurisdictions is obtained information must meet a minimum rule before it can be admitted into a legal proceeding. Countries and their political subunits (states, provinces, etc.) have different rules or standards for admitting evidence. However, it does not end there. Even within a country different rules may apply to different venues, such as criminal proceedings versus civil proceedings. In the United States, for example, there are proceedings where the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) do not apply, such as extradition or rendition; issuing an arrest warrant, criminal summons, or search warrant; a preliminary examination in a criminal case; sentencing; granting or revoking probation or supervised release; considering whether to release on bail or otherwise; and where other statutes or rules may provide for admitting or excluding evidence independently from the rules (FRE Rule 1101, Applicability of the Rules). Harbeck and Yoonji (2010) also discuss the admittance of Internet-based information, such as Wikipedia entries, for use in immigration hearings, which are not governed by the FRE. Suffice to say, there can be exceptions, but for the vast majority of matters of importance, such as a civil and criminal proceedings, rules will act as gatekeepers, determining what gathered information can be presented or considered as evidence in a proceeding.

One of the initial barriers for admitting information into evidence is whether it is relevant or not to the issue at hand. If information has nothing to do with a particular issue, i.e., it isn’t relevant, it can’t be admitted as evidence. All countries with a common law foundation usually have this requirement. However, even countries which are not entirely common law based, such as China, require that information presented must be relevant (Hura, 2011).

The second barrier in determining whether information can be admitted into evidence often hinges on the issue of its authenticity. In the United States, this means is the evidence “what it purports to reflect” (FRE, 901). Canada has a similar definition, specifically, Section 31.1 notes “Any person seeking to admit an electronic document as evidence has the burden of proving its authenticity by evidence capable of supporting a finding that the electronic document is that which it is purported to be” (Canada Evidence Act, Section 31.1). Civil litigation in England and Wales allows the parties to admit a document’s authenticity when it is disclosed to them, unless they serve notice that they want the issue proven at trial (Mason, 2006).

Authenticity concerns are frequently centered on whether the information has been forged or altered, either before it was collected or afterwards. This is one reason that the best evidence rule exists in many jurisdictions, which is simply that one should always present the original document whenever possible as a copy might be altered.3 Other concerns about authenticity go right to the heart of Internet information. In 1999, one United States federal judge described Internet information in these condensing terms:

While some look to the Internet as an innovative vehicle for communication, the Court continues to warily and wearily view it largely as one large catalyst for rumor, innuendo, and misinformation. So as to not mince words, the Court reiterates that this so-called Web provides no way of verifying the authenticity of the alleged contentions that Plaintiff wishes to rely upon in his Response to Defendant’s Motion. There is no way Plaintiff can overcome the presumption that the information he discovered on the Internet is inherently untrustworthy. Anyone can put anything on the Internet. No website is monitored for accuracy and nothing contained therein is under oath or even subject to independent verification absent underlying documentation. Moreover, the Court holds no illusions that hackers can adulterate the content on any website from any location at any time. For these reasons, any evidence procured off the Internet is adequate for almost nothing, even under the most liberal interpretation of the hearsay exception rules found in FED.R.CIV.P.807.

(Teddy St. Clair v. Johnny’s Oyster & Shrimp, Inc., 6 F.Supp.2d 773, 1999)

Subsequent court cases, such as in the landmark case of Lorraine v. Markel Am. Ins. Com, 241 F.R.D. 534, 538 (D. Md. 2007), have not taken such a dismal view of the admittance of Internet-based evidence (Democko, 2012). The issue of alteration at the time of collection and preservation can be addressed with good chain of custody procedures. The general issue of authenticity though requires other investigative actions. We will cover both in detail later.

Depending upon the jurisdiction and venue, information might not be entered as it is considered hearsay. Generally hearsay is information provided in a proceeding which is not presented by the person who saw, heard, or said it. In the United States, hearsay is “a statement, other than one made by the declarant while testifying at the trial or hearing, offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted” (FRE, Rule 801 (c)). In the United Kingdom, hearsay in criminal proceedings is “…a statement not made in oral evidence in the proceedings that is evidence of any matter stated” (Crown Prosecution Service, Criminal Justice Act 2003, Section 114 (1)). However, there are exceptions to when hearsay information can be presented. One of the notably ones is the business rule exception. Many jurisdictions allow business records, including computerized records, to be admitted into evidence if they were made in the usual and ordinary course of business. The reason being is they are most likely to be accurate and reliable for the sake of a business continuing to operate.

Some jurisdictions have legal proceedings, out of the jury’s earshot, where both parties can object to evidence’s admittance. If the information is admitted into evidence it can be an appeal issue, depending upon the type of proceeding. Others will allow the jury to decide the merits of each piece of evidence. For our purposes, online or Internet evidence is ESI, collected from the Internet, which has been properly collected, preserved, and for which a foundation has been laid for its admittance and/or consideration into a legal forum. Conversely, digital or electronic evidence is ESI, collected from computers4 or electronic media, which has also met all the legal requirements for admittance and/or consideration into a legal forum.

Digital versus online evidence

Why differentiate between these two forms of ESI? They are after all “information created, stored, or utilized with digital technology.” They both can be easily modified or deleted. They can both contain “metadata.”5 Additionally, they both can be quite voluminous. We differentiate the two because of the dissimilar manner in which they are collected as well how each are susceptible to modification in a different manner.

Until very recently the prevalent manner digital evidence was collected and processed was from a “dead” machine. A hard drive was imaged and all examination was done on a bit-by-bit copy of the original media. Live acquisitions of electronic data were undertaken but usually only under special circumstances. The general rule of thumb was one never examines original media.6 Additionally, the person collecting digital evidence also have direct access to the media containing the information, be it a computer or server. Even with the advent of remote acquisitions of data over a network, including the Internet, the examiner has some control of the target system.

Contrast such procedures with collecting online evidence. The ESI collected from the Internet is always a live acquisition. The investigator has no ability to control the original media that contains the online data. The server might not even be in the same jurisdiction, let alone the same state, province, or country, as the investigator.

Both digital evidence and online evidence are easily susceptible to modification. However, digital evidence on a hard drive or electronic media can be seized and maintained. It can be imaged and secured, allowing the investigators to use only the duplicate image for examinations. The system that contains the data can be secured. Even in a civil setting, once pertinent ESI is identified on a computer or network, it is secured until it can be provided to opposing parties with potential penalties for spoliation.

Again, contrast this to online data collection, which is merely a snapshot of what the ESI was on a particular date and time, on a website, social networking site, etc. The ESI may also only exist temporarily, such as in the case of instant messaging or chats session, and could be gone unless it is captured in some manner. Even a forensic examination might not retrieve the entire chat or instant message communication. A website might change minutes after it was first captured. The same can occur with a social networking profile. In fact, frequently the very offender who is suspected of wrongdoing has control to modify or delete the ESI completely. Depending upon the circumstances, an offender in custody could even alter a website using a mobile phone or direct a confederate to do so at their behest. In either case the offender changes ESI on the original media that is not under the control and custody of the investigator.7

Consider for the moment this example. A murder has occurred in a car. Police seize the car and preserve it. It is locked in storage, under police guard. The same thing occurs when police seize a computer. They lock it up and preserve it under police custody. Contrast this scenario to a murder that takes place in a park. Police do their best to capture the murder scene, taking pictures and searching for evidence, but they can’t seize the park. Depending upon the circumstances, they may post a guard until they are satisfied they have collected everything, but in the end the park is not seized. They can’t maintain the scene exactly as it was at the time of the murder. This is the same with online ESI. It is captured at a particular date and time, which is preserved and secured. But the original data is subject to change, just like the park which is a murder scene. Depending upon how well the investigator documented the capture of the online ESI will determine if it can be authenticated and admitted into evidence.

Building a foundation

Thus far we have generally discussed the legal issues of relevancy, hearsay, and authentication. Let’s now focus on putting them into a useful context for the investigator tasked with gathering ESI. The first two issues are something that investigators have little control over. For instance, they can’t make ESI relevant if it has nothing to do with an issue. With few exceptions, investigators have little impact on whether ESI is ruled as hearsay or not. Additionally, they can’t control whether ESI ruled as hearsay can be admitted under a jurisdiction’s numerous exceptions to the rules. The last issue, authentication, is impacted to a much greater extent by the investigator’s actions. However, in the end authentication, like relevancy and hearsay are all argued by attorneys and decided by judges and/or juries. The investigator’s task is to conduct their activities in a manner that maximizes the potential for the collected ESI to be admitted into evidence. In other words, their collection efforts must focus on gathering the “best” ESI and provide their legal authority with a good basis to argue that it should be admitted into evidence. Towards that goal, lets first turn to investigative planning, which can assist greatly in addressing all three issues. We then will follow up with some specifics in regard to authentication.

Investigative planning

Few individuals would attempt to build a house without some idea or blueprint for its construction. To do so is foolhardy as important steps may be needlessly repeated or missed, resulting in delays or worse the structure’s collapse. High-tech investigations involving the collection of online ESI are no different. One must have some idea what they are investigating, be it an administrative, civil, or criminal manner and how they are going to proceed. “Documented plans focus an investigation from the start while providing a blueprint for investigators to follow” (Bowker, 1999, p. 25). A properly crafted plan will greatly aid in making sure that collected ESI can be admitted into evidence. Bowker (1999) further elaborates an investigative plan functions to:

• focus the investigative process to ensure that all litigation elements are addressed;

• limit unnecessary procedures and step duplication;

• coordinate the activities of numerous personnel on large cases;

• provide stability to the investigation if staff changes occur

• enhance communication with legal authorities by providing an outline of the investigation and identifying strengths and weaknesses in the case;

What about online investigations in which there is no criminal violation, referred to in the United Kingdom as “open-source investigations”? (Association of Chief Police Officers in the United Kingdom, 2007). Is a plan still warranted for law enforcement conducting open-source investigations? We believe it is. The Good Practice Guide for Computer-Based Electronic Evidence (2007), from the Association of Chief Police Officers in the United Kingdom (ACPO Guide) notes:

There is a public expectation that the Internet will be subject to routine ‘patrol’ by law enforcement agencies. As a result, many bodies actively engage in proactive attempts to monitor the Internet and to detect illegal activities. In some cases, this monitoring may evolve into ‘surveillance,’ as defined under RIPA 2000. In such circumstances, investigators should seek an authority for directed surveillance, otherwise any evidence gathered may be subsequently ruled inadmissible… (p. 13).

US law enforcement should have similar concerns, particularly as such efforts may have a chilling effect on the citizenry’s First Amendment rights.8 Benoit (2012) observed that Maryland Homeland Security and Intelligence Division (HSID) of the Maryland State Police (MSP) conducted an 18-month covert surveillance of anti-death penalty and anti-war activists in which emails were exchanged between an undercover trooper and activists, and the trooper attended various meetings. No criminal activity was detected but the investigation became public. Benoit (2012) quotes the official report as reflecting “…the surveillance undertaken here is inconsistent with an overarching value in our democratic society - the free and unfettered debate of important public questions. Such police conduct ought to be prohibited as a matter of public policy.” Benoit (2012) observes that FBI guidelines address these sensitivities and have two levels of investigative activity; one called an assessment and the second a predicated investigation. Both levels require an authorized purpose. He further notes:

Although the Guidelines do not govern state, local, or tribal law enforcement agencies, they can be instructive. Police agencies that seek to collect information about individuals or groups who engage in protected First Amendment activities can ensure that their conduct is unrelated to the content of the ideas or expressions of the individuals or groups by documenting the purpose for their information gathering or investigative activity. By taking this action, departments can help ensure that their investigative activity is not only consistent with its law enforcement mission but also that the activities in furtherance of their objectives remain related to and in the scope of the authorized purpose. For example, a state or local agency charged with protecting a community may seek to obtain information about an upcoming protest to plan for traffic disruptions, properly allocate its resources, or protect against the commission of crimes. However, the agency should not engage in the investigative activity if the purpose is to discourage the protestors from lawfully exercising their rights.

Investigative components

Bowker (1999) notes that investigative plans have four components: a predication, elements to prove, preliminary steps, and investigative steps. A predication is a brief statement justifying why the investigation is being commenced. As noted above, it is very important that the particular justification be spelled out. Generally, a predication has three features: the basic allegation, the allegation’s source, and date the allegation was made. Predications for open-source investigations, where there is no specific allegation, should reflect a purpose, such as community protection during a specific event, and should also include a fixed duration for the investigative activity. If a specific wrongdoing allegation is uncovered the plan can be amended to focus on the statutory elements to establish a violation. A well-written predication provides the documentation foothold for the investigative steps that follow. The next critical component is a delineation of the elements needed to establish a violation occurred. Bowker (1999) notes:

This component must clearly reflect what is needed to establish a criminal violation, thus focusing the investigation and providing a framework for the steps that follow. At a minimum, this component should contain all of the statutory elements and any special jurisdictional issues, such as venue and statutes of limitations (p. 23).

The next component is a listing of the preliminary steps an investigator will employ to obtain basic background information on the victim or complainant and the suspect(s) if known. A basic Internet search, such as “Googling” for public information, is one such step. Others include online searches of public records, such as Whois and Internet registries or incorporation papers and financial reports filed with government agencies. Other steps may include reviewing agency records on prior allegations or investigations; conducting an in-depth complainant interview; and/or conducting a criminal background check of pertinent parties. Typically, preliminary step completion does not require a great expenditure of time or resources. The next part of the plan is the more specific or focused investigative steps needed to resolve and complete the investigation. They lay out the general parameters needed to establish that an infraction has occurred and each step should parallel the statutory elements of a violation. Investigative steps include:

• victims and/or witnesses to be interviewed;

• identifying and securing any legal process/authority needed for evidence collection;

• identifying ESI (digital and online) and any other evidential items (documents, weapons, contraband, etc.) to be collected and from where;

Following a plan will provide an outline for any final report needed to document the investigation. Plans can be tailored for civil, criminal, or administrative violations. Boilerplate plans can be created for investigations which are frequently conducted with appropriate modifications tailored to meet a current allegation. Investigators should also realize that plans can be modified as warranted based upon new uncovered information or new investigative steps needed. For instance, if one is investigating a cyberstalking case and uncovers information pointing to child pornography, the plan, and subsequent legal authority, can be modified to incorporate the elements and steps needed to establish that new allegation (civilian investigators should STOP and call law enforcement when child pornography is discovered).

Authentication

We noted previously that authentication involves proving an item is what it purports to be. It sounds simple until one considers that online ESI, such as from social media, can be easily altered, quite often easier than other digital ESI. The Internet by its very nature allows users to modify or delete data on the fly, even via mobile devices. However, online ESI can be authenticated provided proper attention is given to its collection. Chief US Magistrate Judge Paul W. Grimm noted in Lorraine v. Markel Am. Ins. Com, 241 F.R.D. 534, 538 (D. Md. 2007) “…the inability to get evidence admitted because of a failure to authenticate it almost always is a self-inflicted injury which can be avoided by thoughtful advance preparation” (p. 17). Investigative planning provides some of that advance preparation. This section will provide some further guidance for authenticating online ESI. However, it is by no means an exhaustive list. As Judge Grimm also observed in the above case “…courts have been willing to think ‘outside of the box’ to recognize new ways of authentication” (p. 36). As such we will only be providing a general outline of the “box,” encouraging investigators to use their imagination and resourcefulness to provide new dimension to the authentication issue. Before commencing it is important to understand there are two basic issues with authenticating online ESI. Merritt (2012) described these two issues in describing social media evidence, which is really applicable to all online ESI. She writes:

Both components of social media evidence must be authenticated. The proponent must introduce evidence ‘sufficient to support a finding’: (1) that the original communication is what the proponent claims and (2) that the tangible download accurately reflects the original message. A plaintiff offering evidence of a defendant’s blog post, for example, must offer proof ‘sufficient to support a finding’ that the defendant was the person who posted the information and that a screenshot of the blog accurately reflects the post. Sometimes the same evidence will accomplish both ends, but a litigant must focus on meeting both goals (p. 52).

Let’s deal with the first issue raised by Merritt that the communication is what it purports to be, namely the communication or post was created by a particular person or on the behalf of an identity. This authenticating issue can be covered under the following five broad categories: (1) content/appearance; (2) content ownership; (3) witnesses; (4) digital ESI; and (5) confession or admission.

Content or appearance relates directly to the text or other information, such as an image, contained in a communication. Is there something in the communication that reflects the author or something consistent with what the author would compose? Examples include but are not limited to the content containing:

1. a work or personal email address;

2. use of real name, known nickname, and/or screen name;

3. telephone number, address, image, or other identifying information; text contains information consistent with known communication from the author;

4. patterns or phrases regularly used by the suspected author;

5. the presence of identifying web addresses, including dates;

6. the ESI content metadata reflects potentially identifying information.

The ESI content ownership involves tracing the post or content to the location from which it was posted. In the case of a website, this would be the registered owner of the site. Identifying a post from a social networking profile could include who owns the profile and what does their profile reflect that can be associated with the owner. Additionally, an online post might contain global positioning information or that the post was made from a mobile device. The duration that the information has existed on a site may also be a method to show ownership. If the message was not at least approved by the site, why was it allowed to be maintained on the site for an extended period of time? While much of this information may be collected online, there is much in the way of identifying background information that may require legal process served on a particular Internet service provider (ISP). Information provided by the ISP may point to the actual location from which a post was made and its owner.

Finally, do not forget that it may be necessary to also secure information from the victim’s or a witness’s ISP as well to show content ownership. For instance, a victim receives a threatening message through their social networking account from a John Smith profile, from which there are literally thousands of profiles with the same name. They printout the post and provide a hard copy. To determine which of the John Smith profiles sent the message it might be necessary to obtain records from the victim’s ISP to trace the message back to its source. Additionally, if there is some concern that a potential victim fabricated the message, the obtained ISP records may provide information to refute or verify their statement.

Obtaining a witness statement seems pretty self-evident. However, the witness must be able to articulate facts that authenticate the communication. For instance, did they see the person post the message or did they receive information from the person confirming that they posted the communication? And do they still have it? Were they a party to the communication and captured it, such as in the case of an instant message or may be they used software to record the communication live.9 Additionally, in reviewing a communication a witness may be able to confirm that information it contains was only known by a particular person, i.e., the author. They may also be able to provide details that point to the suspect as being the message’s originator. For instance, they report that they left the suspect alone at his computer on a particular date and time and information from the ISP places the message coming from his computer during the same time frame.

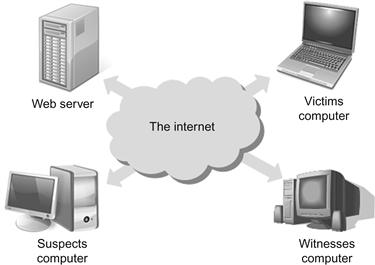

Digital ESI, if it can be obtained, can’t be discontinued in its importance in further authenticating online ESL. If the information, in whole or part, can be traced to a computer controlled by a specific suspect this could be significant in authenticating the communication and its author. Digital ESI may also provide other information, such as a suspect’s repeated access to a site or profile. This can point to circumstantial evidence that the suspect knew information was posted and took no action to remove it. Additionally, don’t forget that digital ESI may also be obtained from the victim’s computer or even a witness who opened the site in a browser (Figure 4.1).

It would seem obvious that a suspect’s confession would be an exceptional piece of information to authenticate ESI. However, do not be content with just a general statement that they “did it.” Go for details, such as is this your account, did you post this message, when, why, and from where (including which device). Even if a full confession can’t be obtained, an admission of any relevant information that could tend to authenticate the ESI may be very important. For instance, a suspect who acknowledges that a particular profile is theirs, that they never gave account access to anyone, nor have they ever suspected their account was hacked, will have a hard later attributing a threatening post to a friend with access or a hacker.

Finally, it is important to understand that one should try to maximize the number of authentication categories addressed during an investigation. In Griffin v. State, 419 Md. 343, 347-48 (Md. 2011), a conviction was reversed on appeal due to authentication issues. In this case, printouts from a MySpace profile that contained threatening statements, purportedly made by the suspect’s girlfriend towards a state’s witness, were originally authenticated based solely on the lead investigator’s testimony about the profile. The investigator noted the profile contained her picture, her birth date, her nickname, and other details. Rashbaum et al. (2012) noted that appellate court found this was insufficient due to concerns about possible fraud. They further observed the appellate court concluded other steps, such as interviewing the girlfriend, obtaining information from the respective ISP, and collecting digital ESI from the pertinent devices, would have provided proper authentication. The point here is do not stop with only one category of authentication if at all possible. Additional authentication could have included records directly from MySpace potentially including the Internet Protocol (IP) address of the users logging into MySpace.

Merritt’s second authentication issue is that the tangible download accurately reflects the original message. This is the actual mechanics of collecting and maintaining online ESI and goes to the heart of chain of custody issues. One must be able to report how they collected the online ESI, including the date, time, and from where it was collected (website, blog, social networking site, file sharing interface, etc.). This is very important. Seng (2009) describes a Canadian copyright infringement case where an application for obtaining numerous ISP addressees was denied. In this case the applicant, rather than the actual investigator who developed the automated process for capturing the screenshots and ISP address, provided the data for the affidavit. The applicant simply did not have the firsthand knowledge to support the affidavit seeking the ISP order. Equally important is investigators must be able to establish that the data they collected was not changed. If a hard copy printout was made the person who printed it must be able to testify the hard copy being presented was the result of their efforts.10 However, what about electronic copies, which are now really digital ESI? How can they be authenticated? A hash value must be calculated either during the actual collection of the data or as soon as possible after the data is saved electronically. This hash value will serve as a verification that the data has not been tampered with since its collection. The collector can then authenticate the collection, given their proper documentation of the collection, and its documented chain of custody.

It is clear that investigators should have knowledge of proper procedures for collecting online ESI and be able to articulate what they did to collect the data. However, this knowledge should not be equated with a requirement that all investigators become “experts,” such as delineated in FRE Rule 702.11 Generally, investigators merely need to be able to testify to what they observed and did to collect the ESI and that the ESI they are presenting is what they originally collected.12

Privacy

Online ESI is publicly visible, so are there any privacy concerns or issues for the investigator? Unfortunately, this is not an easy question to answer. There are times when more than what is observed publicly needs to be obtained, such as the ISP information pertaining to an anonymous cyberstalker. Some statutes, such as the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), limit what information law enforcement can obtain from IPS, setting various legal requirements to obtain basic subscriber information (name, location, etc.) and content (emails, social networking posts, blog posts, etc.). However, some jurisdictions have requirements for data that is collected, whether it be from public or private sources. For instance, the European Union (EU) operates under the Protection Directive (Directive 95/46/EC), which requires the protection of individual’s personal data, including that from social media and provides standards for processing that data. Additionally, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), another United States statute, places restrictions on the use of some consumer information, which can include data retrieved from social media.

We will briefly cover these statutes to expose investigators to these issues which can impact their activities no matter their location. For instance, ECPA covers some of the world’s largest ISP and social networking sites, which are located in the United States. Additionally, many of these statutes provide civil and/or criminal penalties for their violation which heightens the need for awareness beyond just getting online ESI admitted into evidence.

This is by no means a complete digest of privacy laws. Each jurisdiction may have its own rules. For instance, the EU’s current Protection Directive is not followed by all European nations, with some having more stringent requirements (European Commission, 2012). The situation is no different in the United States with constitutions in 10 states (Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Montana, South Carolina, and Washington) having provisions that expressly recognize a right to privacy (National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), 2010). NCSL also notes that six states, California, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, and New Jersey, passed laws prohibiting employers from requesting or requiring an employee or applicant to disclose a username or password for a personal social media account. NCSL reports California and Delaware prohibit higher education institutions from requiring students to disclose social media passwords or account information. At the end of 2012, 14 states had introduced legislation which would restrict employers from requesting access to social networking usernames and passwords of applicants, students, or employees (NCSL, 2012).

To further complicate the issue, at time of this text being written, several of these laws are under review or revision. The EU submitted on January 25, 2012, a draft revision to its data protection rules, which will not be fully implemented for 2 years (Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2012). Likewise, Congress is considering changes to ECPA (Savage, 2012). In short, this is only a starting point for the investigator, who is strongly encouraged to review his jurisdiction’s laws and consult with the appropriate legal authority on these issues.

Electronic Communications Privacy Act

ECPA is actually referring to two laws, the Electronic Communications Privacy Act and the Stored Wire Electronic Communications Act. ECPA “…protects wire, oral, and electronic communications while those communications are being made, are in transit, and when they are stored on computers.” There are three provisions of ECPA, which are commonly referred to as: Title I (Wiretap Act)13; Title II Stored Communications Act (SCA); and Title III (The Pen/Trap Statute). The below is a brief ECPA synopsis and the reader is encouraged to review the statute as well as The ECPA, ISPs & Obtaining Email: A Primer for Local Prosecutors (American Prosecutors Research Institute) and Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations (U.S. DOJ).

Wiretap Act (18 U.S.C. § 2510-22)

This provision prohibits the interception of “real-time” communication (wire, oral, or electronic) by someone not a party to the communication. There are exceptions to the prohibition, such as providers engaging in actions to render their service, court authorization, and consent. Many states also have their own version of this federal statute.

Court authorization requires a finding of probable cause and such authorization can only be granted for specific enumerated felony offenses (18 U.S.C. § 2516). Additionally, such authorization is limited to a particularly time frame, 30 days, after which the monitoring must stop or a new authorization obtained.

As noted above, one of the exceptions to interception is consent. However, there are two kinds of consent. The first is one-party consent, which is contained in the federal law and 38 state statutes. The other type is called two-party consent. This means that both parties to the communication have to consent to the monitoring for it to qualify for this exception. There are 12 states (CA, CN, FL, IL, MD, MA, MI, MO, NV, NH, PA, and WA) that require two-party consent(Reporters Committee for Free Press).

Generally, this will not impact an online investigation, unless there is a recording of real-time communication, such as might occur during undercover investigations involving instant message or chatroom interactions. In O’Brien v. O’Brien, Case No. 5D03-3484 (2005) a Florida appellate court ruled that computer monitoring was governed by the state’s wiretap statute, which was patterned after the federal law (18 U.S.C. § 2501). In this case, software captured chats, instant messages, and web browsing by an individual without his knowledge. The trial judge in a divorce proceeding ruled the captured ESI was inadmissible as it violated state law. In short, monitoring software use, depending upon the jurisdiction and how it is used, may violate wiretap statutes.

Stored Communications Act (18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-12)

The SCA protects the privacy of a subscriber’s file contents, which are stored by service providers (ISP) and subscriber records, such as their name, billing information, or IP address, maintained by the ISP (18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-12). SCA places restrictions on the release of this information and provides civil and criminal penalties for improper access to protected information. Like the Wiretap Act mentioned previously there are exceptions to these restrictions. However, these exceptions can be rather complicated, hinging on a variety of circumstances, such as whether the service provider is public or nonpublic; what kind of information is being sought (subscriber details vs. contents); whether the content has been accessed or not by the subscriber (email opened); and how long the content has been in storage unopened (less then 180 days). Compelled disclosure can occur, the method of which must be matched to the type of information requested (subscriber records vs. file content), based upon the circumstances noted above.

It is noteworthy that the legal method, i.e., a subpoena, court order, or search warrant, frequently requires a different and greater standard of proof before its issuance. The more “private” the information the greater the standard of proof must be met for the legal compulsion method. For instance, obtaining nonopened email, in storage less then 180 days, requires a search warrant, which can only be issued upon probable cause. Additionally, depending upon the compelling process, SCA may require the subscriber be notified. Deutchman and Morgan (2005) note:

Three types of legal process are available under the ECPA to obtain content and records information: ECPA warrants, 2703(d) court orders and subpoenas. In addition, depending upon the type of information sought, 2703(d) court orders and subpoenas may require notice to the subscriber. Generally, the more personal the information sought, e.g., email content, the higher the burden of proof for law enforcement to obtain the requisite legal process. The ECPA warrant must be supported by probable cause, the 2703(d) court order by ‘specific and articulable facts,’ and a subpoena typically by relevance (p. 13).

SCA also provides a mechanism for law enforcement to request an ISP maintain records for 90 days, subject to a renewal for another 90 days (Preservation of Evidence, 18 U.S.C. § 2703(f)). This allows investigators time to obtain the proper legal compulsion method (search warrant or subpoena) without concern the records will be deleted by the provider. However, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) (2009) notes there are some caveats:

First, § 2703(f) letters should not be used prospectively to order providers to preserve records not yet created. If agents want providers to record information about future electronic communications, they should comply with the electronic surveillance statutes discussed in Chapter 4. A second limitation of § 2703(f) is that some providers may be unable to comply effectively with § 2703(f) requests, or they may be unable to comply without taking actions that potentially could alert a suspect. In such a situation, the agent must weigh the benefit of preservation against the risk of alerting the subscriber. The key here is effective communication: agents should communicate with the network service provider before ordering the provider to take steps that may have unintended adverse effects (p. 140).

A variable resource for ISP contact information for sending preservation requests or serving the various legal compulsion methods is maintained by SEARCH.ORG at http://www.search.org/programs/hightech/isp/. It is also worth noting that many larger ISP also provide law enforcement guides that are quite useful in understanding what records they maintain, including how long and in what format.

The Pen/Trap Statute (18 U.S.C. §§ 3127-27)

The Pen/Trap Statute provides that a government attorney may seek a court order to approve the installation of a device (pen register) that records outgoing addressing information and another device (trap and trace) to recording incoming addressing information. These devices can either be hardware or software based. The legal threshold for obtaining such an order is “…the information likely to be obtained is relevant to an ongoing criminal investigation” (18 U.S.C. § 3122(b)(2)). These orders may authorize the installation and use of the devices for up to 60 days, which may be extended for additional 60-day periods (18 U.S.C. § 3123(c)).

Historically, these devices were used to determine who a suspect was telephoning (receiving and making calls). The devices only record the addressing information and do not capture the actual communication. However, the statute also covers communication between two computers, such as the IP addresses or Internet headers in an email (both “to” and “from” minus the subject line). The statute does not authorize the capture of the actual content of a “real-time” message, which can only be approved by a Wiretap order. A Pen/Trap order would typically be sought when it is difficult to determine where communication is originating. U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) (2009) reflects:

…a federal prosecutor may obtain an order to trace communications sent to a particular victim computer or IP address. If a hacker is routing communications through a chain of intermediate pass-through computers, the order would apply to each computer in the United States in the chain from the victim to the source of the communications (p. 155).

There are of course exceptions under this statute’s provisions, such as an ISP can install such a device with their consumer’s consent. This statute does not prohibit an individual recording the ISP address from which they are communicating with, such as during a chat session.

EU Privacy Directive

The EU through Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and Council (Directive) has established a privacy right for one’s personal data. Once establishing this right, the Directive restricts how one’s personal data may be collected and used and sets minimum standards for protection of the collected data. Personal data is defined under Article 2(a) as “…any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (data subject); an identifiable person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity.” To further elaborate something as simple an email address can be personal data where it clearly identifies a particular individual (Data Protection Act, 1998, Legal Guidance).

There are two general situations where the Directive is excluded from operation. An EU state may process data in matters concerning public security, defense, state security (including the economic well-being), and in areas of criminal law. The second exception to the Directive is a “nature person in the course of a purely personal or household activity.” The Directive further provides that processing of data can only occur with the data subject’s explicit consent or in regards to a legitimate activity or obligation, such as performance of a contract. The Directive also provides a mechanism for a data subject to correct or have deleted erroneous information about them.

To illustrate the Directive in action, let’s examine a scenario involving a social media investigation pertaining to subject’s employment suitability, a legitimate purpose under the Directive. The investigation is presumably initiated with the explicit consent of the subject. The investigator identifies the subject’s social media presence and proceeds to collect information from various social networking sites, some of which are located within the EU. These EU social networking sites are a “collector” maintaining data covered under the Directive. However, the investigator has now obtained data on the subject from a location in the EU. As a result, they may have become a “collector” or at least a “processor,” covered under Directive’s provisions, including the rules on disclosure, notifications, modifications, data security, and retention.

These provisions would at first blush seem to only apply to identities located in the EU. This is not the case and is of particular concern for non-EU businesses operating in the EU. As a result, at least in the United States, a framework had to be developed to bridge the differences, particularly in regard to data security and retention. In 2000, the U.S. Department of Commerce in consultation with the European Commission developed a “safe harbor” framework. An organization can participate in the US–EU Safe Harbor program but must comply with seven privacy principles and self-certify annually, in writing, to the US Department of Commerce that they continue to comply with those principles. The Safe Harbor Privacy Principles are as follows:

• Notice: Organizations must notify individuals about the purposes for which they collect and use information about them. They must provide information about how individuals can contact the organization with any inquiries or complaints, the types of third parties to which it discloses the information, and the choices and means the organization offers for limiting its use and disclosure.

• Choice: Organizations must give individuals the opportunity to choose (opt out) whether their personal information will be disclosed to a third party or used for a purpose incompatible with the purpose for which it was originally collected or subsequently authorized by the individual. For sensitive information, affirmative or explicit (opt in) choice must be given if the information is to be disclosed to a third party or used for a purpose other than its original purpose or the purpose authorized subsequently by the individual.

• Onward transfer (transfers to third parties): To disclose information to a third party, organizations must apply the notice and choice principles. Where an organization wishes to transfer information to a third party that is acting as an agent, it may do so if it makes sure that the third party subscribes to the Safe Harbor Privacy Principles or is subject to the Directive or another adequacy finding. As an alternative, the organization can enter into a written agreement with such third party requiring that the third party provides at least the same level of privacy protection as is required by the relevant principles.

• Access: Individuals must have access to personal information about them that an organization holds and be able to correct, amend, or delete that information where it is inaccurate, except where the burden or expense of providing access would be disproportionate to the risks to the individual’s privacy in the case in question, or where the rights of persons other than the individual would be violated.

• Security: Organizations must take reasonable precautions to protect personal information from loss, misuse, and unauthorized access, disclosure, alteration, and destruction.

• Data integrity: Personal information must be relevant for the purposes for which it is to be used. An organization should take reasonable steps to ensure that data is reliable for its intended use, accurate, complete, and current.

• Enforcement: In order to ensure compliance with the safe harbor principles, there must be (1) readily available and affordable independent recourse mechanisms so that each individual’s complaints and disputes can be investigated and resolved and damages awarded where the applicable law or private sector initiatives so provide; (2) procedures for verifying that the commitments companies make to adhere to the safe harbor principles have been implemented; and (3) obligations to remedy problems arising out of a failure to comply with the principles. Sanctions must be sufficiently rigorous to ensure compliance by the organization. Organizations that fail to provide annual self-certification letters will no longer appear in the list of participants and safe harbor benefits will no longer be assured (Export.gov, 2012).

As was noted at that start of this section, the EU’s current Protection Directive is not followed by all European nations, with some having more stringent requirements. On January 25, 2012, a draft revision was made to make the protections more uniform. This new Directive will not be fully implemented for 2 years. It is beyond this text’s purpose to fully explore its provisions before it has been adopted by EU states. However, there is one concept which is worth mentioning. The revised Directive strengthens a “…right to be forgotten, which means that if you no longer want your data to be processed, and there is no legitimate reason for a company to keep it, the data shall be deleted” (European Commission Justice/Data-protection, 2012). It is unclear how long ISP operating in the EU will be allowed to retain a person’s record after they want it deleted. However, the implications for those conducting online investigations should be clear. The ability to collect and properly authenticate online ESI may be the only way to obtain evidence if data collectors are directed to delete it without some reasonable retention period.

Fair Credit Reporting Act (15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq.)

In the United States, we often think of FCRA in terms of a credit check, providing a listing of outstanding financial obligations, leans, foreclosures, bankruptcies, etc. However, the FCRA encompasses more than just a “credit check” and can include information gleaned from social networking investigations. Under the FCRA (§ 603. (d)(1) Definitions; Rules of construction (15 U.S.C. § 1681a)), a consumer report is defined as

…any written, oral, other communication of any information by a consumer reporting agency bearing on a consumer’s credit worthiness, credit standing, credit capacity, character, general reputation, personal characteristics, or mode of living which is used or expected to be used or collected in whole or in part for the purpose of serving as a factor in establishing the consumer’s eligibility for: (A) credit or insurance to be used for personal, family, or household purposes; (B) employment purposes; or (C) any other purpose authorized by under Section 604.14

Under the FCRA a consumer reporting agency “…means any person which, for monetary fees, dues, or on a cooperative nonprofit basis, regularly engages in whole or in part in the practice of assembling or evaluating consumer credit information or other information on consumers for the purpose of furnishing consumer reports to third parties, and which uses any means or facility of interstate commerce for the purpose of preparing or furnishing consumer reports” (FCRA § 603. (f) Definitions; Rules of construction (15 U.S.C. § 1681a)). These definitions clearly cover social networking investigations if the purpose is to collect information for a consumer report.

Employers have begun combing social networking sites to determine the suitability to hire and retain individuals. Under FCRA, an employer’s investigative actions are generally excluded from the definition of a consumer report.15 Employers finding it increasing difficult to investigate these accounts on their own frequently turn to third parties to find the information. However, a third party conducting social networking investigations on behalf of an employer does fall under the above definitions. It is therefore very important that investigators conducting such employment suitability investigations on social media understand the FCRA and its provisions. Noncompliance with the FCRA can have both criminal and civil penalties.

Mutual legal assistance

Based upon information contained in the last section, investigators may now be rethinking the wisdom of gathering online ESI if it resides in another jurisdiction, particularly if digital ESI or witness testimony is required from that jurisdiction. However, there are resources available that may be helpful if such assistance is needed within a particular jurisdiction. One of the methods for reaching out for assistance in criminal investigations is through mutual legal assistance (MLA). MLA refers to:

…the provisions of legal assistance by one state to another state16 in the investigation, prosecution, or punishment of criminal offenses. Given the trans-border nature of criminality, such as organized crime, trafficking in persons and drugs, smuggling in persons, and so forth, mutual legal assistance is an invaluable tool. Mutual legal assistance is usually governed by bilateral or multilateral legal assistance treaties that regulate the scope, limits, and procedures for such assistance, although domestic legislation will suffice in many cases. Treaties are often supplemented by domestic legislation in a criminal procedure code or as a separate piece of legislation. Mutual legal assistance may also be given informally through bilateral cooperation and the sharing of information between policing or judicial officials in different states

(Connor et al., chap. 14, p. 427).

MLA can take time, particularly if prior professional relationships have not been developed through organizations, such as the High Technology Crime Investigation Association (HTCIA) or High Tech Crime Consortium (HTCC) (www.hightechcrimecops.org). Additionally, MLA is limited to universally recognized crimes and not those of a “political nature.” Two major MLA are the Hemispheric Information Exchange Network for Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters and Extradition (the “Network”), which covers all of the Americas located at http://www.oas.org/juridico/mla/en/index.html and the European Union Second Additional Protocol to the European Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters located at http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/182.htm.

For civil investigations the professional relationships developed through HTCIA (www.htcia.org) and HTCC (www.hightechcrimecops.org) can be extremely beneficial as MLA do not apply.

General guidance

There are numerous public resources for how to initially collect digital ESI from computers, many of which are from the United States.17 Unfortunately, the specifics of collecting online ESI have been historically lacking. There were some early efforts to address online ESI. For instance, The National Cybercrime Training Partnership18 distributed about 50,000 copies of The Cyber Crime Fighting—The Law Enforcement Officer’s Guide to Online Crime in 2000 (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2002). This guide was noteworthy as it discussed at length not only procedures for seizing computers but also was one of the first documents to discuss steps for investigating online crimes. The guide discussed questions to ask complainants and suggested obtaining hard copy printouts or file downloads from complainants. However, it did not discuss steps for investigators to secure online data themselves. Subsequent guides, such as the Secret Services, Best Practices For Seizing Electronic Evidence V.3: A Pocket Guide for First Responders, focus almost entirely on computer seizure with only a brief mention of interpreting email header information. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) (2007) Investigations Involving the Internet and Computer Networks does discuss very basic online ESI collection procedures, such as taking screenshots, using the “Save As19” command, and special software for capturing websites. Additionally, the NIJ guide mentions documentation procedures, which include making sure to note the data and time of collection and checking to insure the data was obtained. However, there is no mention of chain of custody concerns, such as securing the data or creating a hash value20 after collection.

Why this inadequate treatment of online ESI collection? There may be several reasons. The first may be the erroneously perception that screenshots or website captures are not as important as finding digital ESI on the suspect’s hard drive. This may be true if improper techniques are used which lead to admissibility issues, such as authenticity and hearsay. However, one must recognize that the evidence may sometimes only be found online and not on a suspect’s computer hard drive. For instance, a screen capture may be the only recourse to gather data from a live chat session or private instant message. With the plethora of anti-forensic techniques, an examiner may be unable to retrieve the incriminating social networking post or message from the suspect’s computer. As noted in the previous section, the EU’s “right to be forgotten” principle may also have a negative impact on ESI being provided by an ISP.

Online ESI can be easily changed during an investigation. There also may be jurisdictional issues that make getting the data from an ISP more difficult or too time-consuming. The ACPO Guide provides the following commentary which is applicable to all jurisdictions:

Evidence relating to a crime committed in the United Kingdom may reside on a website, a forum posting or a web blog. Capturing this evidence may pose some major challenges, as the target machine(s) may be cited outside of the United Kingdom jurisdiction or evidence itself could be easily changed or deleted. In such cases, retrieval of the available evidence has a time critical element and investigators may resort to time and dated screen captures of the relevant material or ‘ripping’ the entire content of particular Internet sites.

The second reason is the general lack of understanding of how to accomplish online ESI collection. This explanation parallels that which occurred in the late 1980s with digital ESI collection and analysis. Specifically, there were few tools to accomplish computer forensics. Those tools that did exist were not designed originally for forensics, but were adopted from other purposes. Few understood how to accomplish digital ESI collection and analysis. As time went on forensic tools were created specifically for digital ESI collection and analysis. With the development of these tools specific procedures came into existence that guided their further development and their proper use. Currently dealing with online ESI is where the field was with digital ESI in the late 1980s. There are few properly designed tools for this specific purpose. Most tools still used were developed for other purposes. A few agencies, such as the Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) Task Forces (TF), have developed standardized investigative methods for online ESI. However, this is unique in the law enforcement community. The vast majority of law enforcement agencies have no standard methodologies in place for the collection and analysis of online evidence. Just like what occurred with computer-based ESI, investigators are learning to adapt and develop to meet the challenge of collecting online ESI. Shipley (2007) notes:

Current law enforcement investigative methodologies for the Internet are varied and many. Some agencies have dedicated the necessary resources to conduct investigations and still many others have ignored the Internet and the crime conducted there, either out of ignorance or negligence. No standard process currently exists to guide an investigator, at any level within the government (local, state or federal), military or those investigating the Internet for a corporation. This has caused a lack of understanding among those assigned these tasks, and have caused the development of a variety of practices within this community. To add to the lack of consistent practices, the lack of specialized tools in this area has driven the adoption of tools specifically designed for other purposes. These tools have sometimes provided the investigator with insufficient support for best evidence practices. However, investigators ever adapting to their changing world, proceeded ahead and have put many criminals in prison based on their ability to collect evidence from the Internet with tools not designed for evidence collection.

A good starting point for developing procedures is the four principles noted in the ACPO Guide. Although, written primarily for computer-based digital ESI, the ACPO Guide is one of the few resources which actually discusses collecting online ESI. The guide also discusses undercover online investigations and open-source investigation, which is proactively patrolling the Internet for evidence of crimes. Additionally, these principles are useful for online ESI, as they stress that data must not be changed; those accessing data should have a certain level of competency; and that documentation and chain of custody are important considerations. These are all key components to making sure online ESI can be admitted as evidence. Also, these four principles summarize nicely concepts found in other public resources on electronic data collection.21 Finally, although noted for law enforcement, the evidence collection procedures for criminal law are universally more stringent than those in any other proceeding. As such, anyone serious about getting their online ESI admitted as evidence in any legal forum must strongly consider the following ACPO Guide principles:

Principle 1: No action taken by law enforcement agencies or their agents should change data held on a computer or storage media which may subsequently be relied upon in court.

Principle 2: In circumstances where a person finds it necessary to access original data held on a computer or on storage media, that person must be competent to do so and be able to give evidence explaining the relevance and the implications of their actions.

Principle 3: An audit trail or other record of all processes applied to computer-based electronic evidence should be created and preserved. An independent third party should be able to examine those processes and achieve the same result.

Principle 4: The person in charge of the investigation (the case officer) has overall responsibility for ensuring that the law and these principles are adhered to. (p. 4).

Early in the digital evidence process development, the NIJ Technical Working Group on Digital Evidence (TWGDE) produced the document “Electronic Crime Scene Investigation, A Guide for First Responders,” which outlined a four stage process for dealing with digital evidence. Those four stages were collection, examination, analysis, and reporting of the digital evidence.22 Shipley (2007) narrowed the focus for online ESI to three steps: collection, preservation, and its presentation. There may be occasions where analysis may be needed, such as examining metadata. However, using the best collection procedures feasible will facilitate such additional steps if needed. Shipley (2007) describes these three basic steps as follows:

Collection: Includes the actual capture of content viewed by the user. This can be a webpage or items on a webpage, such as image files, music files, or documents. It can also be instant message conversations or chat conversations using a variety of applications designed for that purpose.

Preservation: Includes the treatment of this digital evidence using the concepts and principles learned from computer forensics when dealing with digital evidence (Figure 4.2).

a. Don’t change the evidence if possible.

b. Collect the evidence in a verifiable manner.

c. Maintain a proper chain of custody of the evidence.

Presentation: Means the actual viewing offline of the evidence in a manner simulating its real-time collection. This could include viewing chat logs or video files of the websites visited or the real-time chat sessions.

Conclusion

This chapter provided an overview of online ESI. The focus was not to make investigators legal experts. However, we hopefully provided the general knowledge to gather the “best ESI” to ensure any legal authority has a good basis to argue that it should be admitted into evidence. We firmly believe that with proper planning investigators will go a long way to insure, in Judge Grimm’s words, there are no “self-inflicted injuries” with regard to authentication. We cannot stress enough that today’s legal environment mandates that investigators: (1) don’t change the evidence, if possible; (2) collect it a verifiable manner; and (3) maintain a proper chain of custody. This book’s remaining chapters will provide in-depth techniques based upon these legal mandates to insure online ESI can be admitted into any legal forum.

Appendix

xx

Further reading

1. Adams, J. (n.d.). BrainyQuote.com. Retrieved from http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/j/johnadams134175.html/.

2. Association of Chief Police Officers in the United Kingdom. (2007). The good practice guide for computer-based electronic evidence. Retrieved from http://www.7safe.com/electronic_evidence/ACPO_guidelines_computer_evidence.pdf/.

3. Benoit, C. (2012). Picketers, protesters, and police the first amendment and investigative activity. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/law-enforcement-bulletin/august-2012/picketers-protesters-and-police/.

4. Bowker A. Investigative planning creating a strong foundation for white-collar crime cases. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 1999;68(6):22–25.

5. Canada Evidence Act. OAS—Organization of American States: Democracy for peace, security, and development. N.p. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.oas.org/juridico/mla/en/can/e/.

6. Connor VM, Rausch C, Albrecht H, Klemencic G. Mutual legal assistance and extradition. Model codes for post-conflict criminal justice Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace; 2008.

7. Crown Prosecution Service Hearsay. (n.d.). Legal guidance: The Crown Prosecution Service. Retrieved from http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/h_to_k/hearsay/.

8. Data Protection Act. (1998). Legal guidance. Retrieved from http://www.ico.gov.uk/upload/documents/library/data_protection/detailed_specialist_guides/data_protection_act_legal_guidance.pdf/.

9. Deutchman L, Morgan S. The ECPA, ISPs & obtaining E-mail: A primer for local prosecutors Alexandria, VA: American Prosecutors Research Institute; 2005; Retrieved from <http://www.ndaa.org/pdf/ecpa_isps_obtaining_email_05.pdf/>.

10. Democko B. Social media and the rules of authentication. University of Toledo Law Review. 2012;43(Winter):367–405.

11. Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986. (ECPA). (n.d.). IT.OJP.GOV home. Retrieved from <http://www.it.ojp.gov/default.aspx?area=privacy&page=1285/>.

12. Electronic Crime Scene Investigation: A Guide for First Responders, Second Edition. (2008). Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice. Retrieved from < https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/219941.pdf>.

13. EUR-Lex—31995L0046—EN. (n.d.). EUR-Lex. Retrieved from <http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31995L0046:en:HTML/>.

14. European Commission Justice/Data-protection. (2012, February 20). How does the data protection reform strengthen citizens’ rights? Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/justice/data-protection/document/review2012/factsheets/2_en.pdf/.

15. European Commission. (2012). Commission proposes a comprehensive reform of data protection rules to increase users’ control of their data and to cut costs for businesses-press release. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-12-46_en.htm?locale=en/.

16. Export.gov. (2012). U.S.–EU safe harbor overview. Export.gov—Home. Retrieved from http://export.gov/safeharbor/eu/eg_main/.

17. Fair Credit Reporting Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq.

18. Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE). (2011). Washington: U.S. G.P.O.

19. Griffin v. State, 419 Md. 343, 347-48 (Md. 2011).

20. Harbeck D, Yoonji K. Is the Internet “Voodoo”?: Evidentiary weight of Internet-based material in immigration court. Connecticut Public Interest Law Journal. 2010;10(I):3–12.

21. Hura D. China’s new rules on evidence in criminal trials. International Law and Politics. 2011;43:740–765.

22. Insa F. The admissibility of electronic evidence in court (A.E.E.C.): Fighting against high-tech crime results of a European study. Journal of Digital Forensic Practice 2007;285–289.

23. Investigations involving the Internet and computer networks. (2007). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice. Retrieved from < https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/210798.pdf>.

24. Lorraine v. Markel Am. Ins. Com, 241 F.R.D. 534, 538 (D. Md. 2007).

25. Mason S. Proof of the authenticity of a document in electronic format introduced as evidence Pittsburgh: ARMA International Educational Foundation; 2006; Retrieved from http://www.mnhs.org/preserve/records/legislativerecords/docs_pdfs/Proof_of_authenticity_of_a_document.pdf/.

26. Merritt D. Social media, the sixth amendment, and restyling: recent developments in the federal law of evidence. Touro Law Review. 2012;28:27–54.

27. National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). (2010). Privacy protections in state constitutions. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/telecom/privacy-protections-in-state-constitutions.aspx/.

28. National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). (2012). Employer access to social media passwords. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/telecom/employer-access-to-social-media-passwords.aspx/.

29. O’Brien v. O’Brien, Case No. 5D03-3484. Northern District of Florida (2005).

30. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Proposal for a Regulation of European Parliament and of the counsel on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation) Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2012.

31. Pen/Trap Statute (18 U.S.C. §§ 3127-27).

32. Rashbaum K, Knouff M, Murray D. Admissibility of non-U.S electronic evidence. Richmond Journal of Law and Technology. 2012;XVIII(3):58–76.

33. Reporters Committee for Free Press. Can we tape? Retrieved from http://www.rcfp.org/taping/.

34. Savage C. Panel approves a bill to safeguard e-mail. The New York Times 2012;7.

35. Seng D. Evidential issues from pre-action discoveries: Odex PTE LTD v. Pacific Internet Ltd. Digital Evidence & Electronic Signature Law Review. 2009;6:25–32.

36. Shipley, T. (2007). Collecting legally defensible online evidence. Vera Software. Retrieved from <http://veresoftware.com/uploads/CollectingLegallyDefensibleOnlineEvidence.pdf/>.

37. Shipley T, Reeve H. Collecting evidence from a running computer: A technical and legal primer for the justice community Sacramento: SEARCH, The National Consortium for Justice Information and Statistics; 2006; Retrieved from http://www.search.org/files/pdf/CollectEvidenceRunComputer.pdf/.

38. Stored Communications Act (SCA) (18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-12).

39. Tech Terms Computer. http://www.techterms.com/.

40. Teddy St. Clair v. Johnny’s Oyster & Shrimp, Inc., 706 F. Supp. 2d 773 (S.D. Texas 1999).

41. U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). (2009). Searching and seizing computers and obtaining electronic evidence in criminal investigations. Silver Spring, MD. Retrieved from <http://www.justice.gov/criminal/cybercrime/docs/ssmanual2009.pdf/>.

42. U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO) (Joint Working Group on Electronic Technology in the Criminal Justice System (JETWG)). ( 2012). Recommendations for electronically stored information (ESI) discovery production in federal criminal cases. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.fd.org/docs/litigation-support/final-esi-protocol.pdf/.

43. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance. (2002). The National White Collar Crime Center: Helping America fight economic crime. Washington, DC. Retrieved from <https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/184958.pdf/>.