Internet Resources for Locating Evidence

This chapter provides the reader with many useful Internet resources to assist in their investigations of a person, a company, or a web location. The websites mentioned are intended to be the investigator’s starting place for locating information. The differences and use of search directories, search engines, and metasearch engines are discussed. This chapter also includes multiple sites that can support the investigator’s identification of email addresses and telephone numbers. Additionally, information is provided to help the investigator identify background data on companies. Throughout the chapter there are tips for conducting effective investigative Internet searches.

Keywords

Bing; Bing Advanced Keywords; Google; Google’s Advanced Operators; Pipl; SearchBug; search directories; search engines; metasearch engines; TouchGraph; ZoomInfo

Some say Google is God. Others say Google is Satan. But if they think Google is too powerful, remember that with search engines unlike other companies, all it takes is a single click to go to another search engine.

Sergey Brin, Google Co-Founder; Jarboe, 2003

Sources of online information

There are many sites that have been around for some time that can be great resources for the investigator. But, online sources are always changing and the investigator needs to be aware of new ones that can assist his investigations. If you find a good site or resource page don’t be afraid to bookmark it and use it. The basics of searching for people, telephone numbers, or businesses online include to always use more than one site. Each site uses different methods and algorithms to identify the data based on your input. Using more than one site increases the likelihood of finding the information you are seeking. Always be sure to evaluate the online resource before relying on the site for investigative purposes. Some sites can advertise certain effectiveness, but when tested against a search engine’s returns you may find it not worth the time or effort to use it. There are pay sites that can give the investigator access to more information than the Internet can, but even these need to be evaluated for their content. Be aware that some pay sites rely on databases that may contained outdated information.

As the investigator spends more time using Internet-based tools to identify information they will find that there are some common search truths. The more common the name, the more likely you will get search returns that may not be correct. The more unique the name, the less search results but the greater the probability the hits will be germane to the investigation. Most free sites have a pay site component which provides more information. Even pay sites frequently allow a basic search to determine whether or not the site has information about your search subject. The information they contain can be substantial or limited. You won’t know until you pay. Costs vary from a onetime payment for one search to a monthly or an annual subscription fee. These sites generally purchase or have access to different public and private databases, the accuracy or timeliness of which may vary. However, many of the sites use the same data brokers as their source of information.

Search services

Many people mistakenly believe that one search is as good as another or that one particular search engine will list everything that is available on the Internet. These misconceptions are simply not true. Kotch (2007) notes there are three types of Internet search services, (1) search directories, (2) search engines, and (3) metasearch engines, each varying in its provided results.

Search directories are hierarchical databases with references to websites. These directories contain websites that are selected by human beings, which in turn list and classify according to a particular search service’s rules. Kotch describes Yahoo! Directory as the “mother of all search directories.”1 Directories do not search webpages but the text contained in the site title and description. This information is composed by the directory editors, which is often based upon content provided by the site owners.

Search engines are “… ‘engines’ or ‘robots’ that crawl the Web looking for new webpages. These robots read the webpages and put the text (or parts of the text) into a large database or index that you may access” (Koch, 2007). No one search engine covers the entire Internet. In June of 2013, Google had 66.7% of the US user’s market share, compared to Bing’s 17.9% and Yahoo! an 11.4% (comScore, 2013). It is interesting to note that Microsoft’s search engine Bing powers Yahoo! searches (Kaushal, 2011). Clearly, Google has the lion’s share of the market place. But what does that mean in size of their respective databases?

It is impossible to know how big Google or Bing’s databases are as that information is considered proprietary. However, try this quick rough comparison. Type in the word “the” into both Google and Bing’s search engines. In July 2013, Google returned 25,270,000,000 results to Bing’s 3,260,000,000. There are likely to be some differences due to how their engines work and collect data, but it would be a safe bet to conclude that Google has a larger database. However, larger does not mean Google contains all the information of Bing and then some. Bing likely has information that Google does not have. Other search engines, such as Ask Network and AOL, Inc., with 2.7% and 1.3%, respectively, of the US market share (comScore, 2013), may also contain information that neither Google or Bing possesses. The important thing to note is that search engines are your best option when you know exactly what you are seeking.

Koch’s last category is metasearch engines. These services search both engines and directories at the same time providing relevant hits from all of them. They can provide a general idea of what is out there. The problem is not all search engines interpret user’s queries in the same manner. The metasearch engine “… has to try to ‘translate’ your query into a language that each search engine will understand. More often than not, they will not try to do so” (Koch, 2007). For a more complex search, the user needs to go to a particular search engine.

Some metasearch engines do have some neat features. For instance, Clusty (http://clusty.com) will group the hits into “clusters.” These clusters, known as clouds, sources, sites, and time, are farther broken down. For instance a Clusty search of the term cybercrime will provide a list of website types this term appears, which is further broken down, such as .gov, .edu, so on. Dogpile (http://www.dogpile.com/), known as Webfetch, in Europe (http://www.webfetch.com/) searches Google, Yahoo!, and other search engines simultaneously. Pandia (http://www.pandia.com) not only conducts simultaneous queries, it also has a pretty comprehensive listing of the various search directories, engines, and metasearch engines out there.

Searching with Google

Searching with Google can be one of the most effective tools the investigator uses during his research. Google was created in 1995 by Larry Page and Sergey Brin at Stanford University, California. Believe it or not Google is actually a word and stands for 1 googol which equals 10 to the power of 100 or 1 followed by 100 zeros. How Does Google do it all? Google has a series of data centers with an undisclosed number of servers in multiple locations around the World (Google, History).

Google Basics

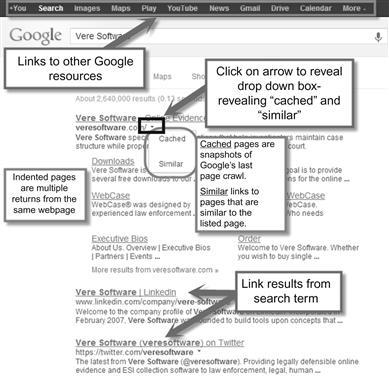

Using Google is as simple as putting in your search terms and pressing enter. The investigator can then scroll through the returns and click on the hyperlinks associated with the returns. The Google results page provides the user with multiple hits on a single page as well as multiple pages. Google searches can often return thousands of result pages. Each page contains links to web artifacts responsive to the search term. That artifact can be a webpage, a document, or an other searchable hyperlinked item found by Google during its web crawling. The blue texts are hyperlinks to the web artifact that was found by Google. Indented links are multiple links to pages within the first webpage found (Figure 12.1).

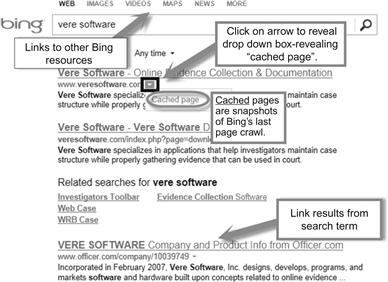

Google also has additional information in a drop-down box at the end of the link that connects to a “cached” page. The cached page is the last copy of the webpage that Google crawled. It could be within days if not weeks of the current page but is also subject to being overwritten and replaced with a newer webpage version. The top of the cached page includes the date and time of the Google web crawl. For the investigator this can be a valuable piece of information. Depending on when Google crawled the site, the last page may contain information different than the current page. Documenting and capturing Google’s cached page of a webpage can therefore be important step to ensure this time snapshot is preserved. Bing’s search also has a cache feature which may not be the same date that Google’s cache page was created. Bing’s cache copy can yet be another piece to an investigative timeline puzzle, warranting similar documentation and preservation (Figure 12.2).

Google has an Advanced Search page in addition to its general search page. After a query is completed, at the bottom of the page results, an Advance Search option is shown. Clicking on Advance Search will bring up a page which assists the user refining their query. Some of the Advanced Search options are the ability to limit the query by excluding certain words, by using an exact phrase, or the inclusion of a number range. The number range can be a year date range to include returns only between two specific dates. Additional functions include limiting the hit returns to a specific language, a region or just a specific website or domain.

Clicking “More” at the top of Google’s search screen will produce a pull-down menu. Selecting “Even More” from this menu provides several additional options that can be beneficial to the investigator. For instance, this section has an area for Patent as well as Scholar searches, the latter of which includes access to not only articles but legal opinions.

Google’s Advanced Operators

Using advanced operators with Google can provide the investigator with an ability to search for and locate more precise information about the specific query terms directly from the search box. We have provided a few of these operators in Table 12.1. A good resource for understanding Google’s Advanced Operators is their guide at http://www.googleguide.com/advanced_operators_reference.html, which provides lists of additional advanced operators and how they are used.

Table 12.1

Useful Investigative Google Advanced Operators

| Advanced Operator Example | |

| Definitions | define:term |

| News headlines | News:topic |

| Google cached pages | cache:url |

| Search within site | site:domain.com |

| Search for links | link:domain.com |

| Term(s) in URL | inurl:term |

| Term(s) in title | intitle:term |

| Term(s) in body text | intext:term |

| Term(s) anchor text | inanchor:term |

| Specific file type | ext:filetype |

| Related sites | related:url |

| URL-related info | info:url |

TouchGraph

Sometimes seeing relationships between individuals is not easy. It can be tough to see connections merely from gathering data and looking at a list, particularly when one is dealing with large numbers. A common law enforcement practice for years has been to place photos on a bulletin board and either organize the photos or draw lines to reflect how they are related. Perez (2008) refers to this as visualization, which “… is a technique to graphically represent sets of data.” Visualization makes the relationships easier to detect and understand. One particular website, TouchGraph SEO Browser (http://www.touchgraph.com/TGGoogleBrowser.html) graphs and “… reveals the network of connectivity between websites, as reported by Google’s database of related sites” (Figure 12.3).

Clicking a result icon will provide details about it, such as the URL where the information was found, a brief description, and additional related sites. The website also allows you to export the data out to a .csv file that can be opened in a spreadsheet to better utilize the information. The data exported includes the URL where the information was found and the title of the site’s page where it was found.

Searching with Bing

Bing, previously known as Live Search, Windows Live Search, and MSN Search, was unveiled in 2009 and was designed “… with a new approach to user experience and intuitive tools to help customers make better decisions, focusing initially on four key vertical areas: making a purchase decision, planning a trip, researching a health condition or finding a local business” (Paczkowski, 2009). Bing’s focus is simply providing results that lead users to decisions to purchase goods or services.

In 2012, Bing started presenting its search results in three columns, (1) search results, (2) a “snapshot” of related searches with associated ads, and (3) a social networking interface, which if approved will connect to a user’s own Facebook profile (Peterson, 2012). According to Harry Shum, a Vice President of Microsoft, this revamping enables “information to flow from search to social networks” (Peterson, 2012). For investigators the first column results are usually the most important results.

Bing is remarkably similar to the layout of Google (Figure 12.4). As with Google simply input in your search terms and press enter. Returns are presented which can be scrolled through. Clicking on the hyperlinks, also shown in blue, will take the investigator to webpage associated with the search hit. The operators are somewhat different. For instance, in Google to query on two terms one uses the + sign. Bing however does a search on all words, without regard to the + sign. Bing provides a cache version of the webpage with a drop-down box at the end of the link that goes to a “cached” page. Bing has its own version of advanced operators, which are referred to as advanced keywords. See Table 12.2 for some of the useful ones. However, Bing does not have its own advanced search page like Google. Finally the resources to locate how to search on Bing are as not numerous as they are for Google.

Finding information on a person

Use multiple sites when Internet searching for an individual will get you a better well-rounded response and data set. There are many sites available on the Internet that can provide the investigator with information on a person. Each varies in the information provided and the requirements for doing a query. Using multiple sites can provide the investigator with a complete picture of the targeted individual. It is best to consider searching as a process, with each following search requiring more specific details for quality results.

These details fall into two general tiers of criteria. Tier one criteria is something that is very specific to that person, such as a photo, birth date, age, home address, telephone number, email address, screen or profile name, close relative, property ownership, or party to a civil or criminal case. These things are not always easy to know but if discovered can later lead to high-quality searches and information.

Tier two criteria is a bit more general and is frequently easier to know. They include such things as employment, occupation, general location (city/state/country), education, hobbies, and associates. These factors coupled with the individual’s name may lead to more specific or tier one information, which again leads to quality searches and information.

Consider for a moment you have a name and where they graduated from high school. With this information you may be able to find an alumni site and find the year they graduated. With the year they graduated you now have their age narrowed down. Additionally, with their high school name you may be able to search for their profile on a social media site, which may lead to photos, where they are located, age/birth date, email address, and their relatives and associates.

Again, all of these can help the investigator identify information about a person. Using a search term of two names in quotes with a plus sign such as “Todd Shipley”+“Art Bowker” can provide the investigator with sites where the two names appear together. (For Bing the search term would be “Todd Shipley” “Art Bowker”, without the plus sign.) This same technique can be used with a name and employment, location, etc (Figure 12.5).

Generally, consider the search process as involving the following: (1) search engine inquiries (2) specific site searches, such as a social networking directory or an identified website, and (3) biological search site, which require one other factor beside names, such as address, age, or relatives to narrow the results. Online court records, inmate searches, and sex offender queries are increasingly available too. They can be considered a biological search as the location where a person lives or lived, along with the date of birth is needed to narrow the results to the target of interest.

At the start of the process is the use of a general search engine (Google, Bing, etc.) or a people search engine, such as Pipl (www.pipl.com). Simply by typing the target’s name into the search box will provide individual page links that contain the name query. However, unless that person’s name is unique you are likely to get results from all over the place, which need to be further refined. Add either a tier one or two level criteria you possess to narrow the results. If there is information present you should have located it. Harvest additional criteria for your searches and document your results. If not, attempt to search a social networking directory. Again, harvest additional criteria for your following searches. Only when you have a tier one level criteria, such as address, age, or relative attempt a biological search using one of the below sites, most of which require a fee to obtain more detailed information:

• 411.com, http://www.411.com

• BRBPub.com, http://www.brbpub.com/

• Dru Sjodin National Sex Offender Public Website, http://www.nsopw.gov/2

• Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Search, http://www.bop.gov/iloc2/LocateInmate.jsp3

• SearchBug, http://www.searchbug.com

• Search Systems, http://www.searchsystems.net

• ZABASEARCH, http://www.zabasearch.com

• ZoomInfo, http://www.zoominfo.com

Don’t forget we have previously discussed the Vere Software Toolbar and its inclusion of multiple sites that can be used for identifying persons on the Internet. Finally, do not consider the search process as a one-direction linear activity. For instance, your site-specific search or biological search reveals some new criteria that you did not possess when you did the search engine queries. You are not precluded from taking that new criteria and doing another search engine query, which may lead to even more leads.

Finding business information

The Internet has provided the opportunity for every company on the planet to make a world-wide presence through the use of websites and social media. With this opportunity most businesses have made liberal use of the Internet to present their products/services and information about their company and its employees. Other sources on the Internet regularly collect information on companies and post it to their websites. Government agencies also routinely make available information about companies. Again, commence your inquires with search engines and progress to these other websites. Be aware that negative results on a government site may reflect that entity is very new, non-compliant with reporting requirements and/or outright fraudulent person or entity. Accordingly document negative results and what government database was searched.

US government sources

Secretary of State’s offices in the United States provide online access to corporation registration records. However, be aware that some states limit how much information is provided online or regular a fee payment. Also consider checking foreign entity records for companies doing business in one state but incorporated in another. The US Security and Exchanges Commission provides online access to a variety of required filings from US Companies. Using these resources, an investigator can identify huge amounts of information about a company or corporation.

In the United States, labor unions which represent private sector employees or are representing US Postal Service employees are required to file annual financial reports and to provide copies of their bylaws/constitution. Additionally, under some circumstances employers and labor relations consultants are required to file disclosure reports. Collective bargaining agreements covering 1,000 or more workers are also on file with the US Department of Labor. All of these records are online and can be searched. One interesting query will allow the user to search by payee for payments from labor organizations. Many states also require unions which represent solely public employees within their state to file annual financial reports.

The US Internal Revenue Service’s website provides information on charities and nonprofit organizations that file the Form 990. These forms can provide information on the targeted organization. Additionally, many states provide online access to professional licensing information on variety of occupations. The following are some useful US government websites to research companies, nonprofit entries, and labor unions:

• Internal Revenues Service (Tax Exempt Organizations), http://www.irs.gov/Charities-&-Non-Profits/Exempt-Organizations-Select-Check

• National Archives, http://www.archives.gov/

• Office of Labor Management Standards, US Department of Labor, http://www.dol.gov/olms/regs/compliance/rrlo/lmrda.htm

• Securities and Exchange Commission, http://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/srch-edgar?

Non-US government sources

The United States is obviously not alone in providing its citizenry online information about businesses operating in their jurisdictions. Many countries mandate companies register and file annual reports with a government agency. Increasingly these records are publicly available and online. Locating these sites can be as easy as doing a Google search (corporation+registration+country of interest). However, we have provided some of the larger sites below:

• Australian Security and Investment Commission, https://connectonline.asic.gov.au/RegistrySearch/faces/landing/bn/SearchBnRegisters.jspx?_adf.ctrl-state=t5t9t1hry_13

• Corporations Canada (provides search for federal corporations as well as links to provincial registries), http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cd-dgc.nsf/eng/cs01134.html

• European Business Register (EBR), http://www.ebr.org/section/1/index.html

• The Registrar of Companies (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland), http://www.companieshouse.gov.uk/

Non-government sources

Individuals and companies need to make sound business decisions and that often requires “due diligence” inquiries on potential partners and investments. Fortunately, governments are not the only entities maintaining records on businesses and nonprofit organizations. Some large data brokers, such as LEXIS-NEXIS®, mentioned in Chapter 6, have information on businesses and nonprofits in their databases. Another such data broker is IRBSearch (www.irbsearch.com). Access to these databases requires the payment of fees and/or a subscription. However, there are other online sites which provide a variety of business data for free or at a small cost. Below are some of the notable ones:

Other business search sites

• Canadian Council of Better Business Bureaus (both businesses and charities), http://www.bbb.org/canada/

• Council of Better Business Bureaus (US) (both businesses and charities), http://www.bbb.org/us/

• CreditRiskMonitor, http://crmz.com/directory/

• Fran Finnegan & Company, http://www.secinfo.com/

• Hoovers, A D&B Company, http://www.hoovers.com

• Manta Media, Inc., http://www.manta.com/

• Search Systems, http://www.searchsystems.net

• Zoom Information, Inc., http://www.zoominfo.com/

Charity/nonprofit resource sites

• Charity 101, http://charitycheck101.org/

• Charity Navigator, http://www.charitynavigator.org/

• GuideStar Nonprofit Directory, http://www.guidestar.org/

• NOZA 990-PF Database Listing, http://www.grantsmart.com/

• Noza Search (Donors), https://www.nozasearch.com/

Finding telephone numbers and email addresses

Finding information about telephone numbers on the Internet can be a little unsatisfying. Unfortunately most records on telephone ownership require the use of legal service on the provider that owns the number. Additionally, some websites may provide dated information on telephones, which can lead to erroneous owner identification. This does not mean the investigator cannot identify certain information about a telephone number. Websites like FoneFinder, http://fonefinder.net/ and PhoneNumber.com, http://PhoneNumber.com can provide the city and state that the number is originally from as well as the service provider controlling the number. This can provide the investigator with the company to send legal service to identify the telephone owner. From an investigative perspective, a search on Google or other search engines can provide the user with places on the Internet that the telephone number has been posted. This may lead to the identity of the person or company connected to the number.

Email addresses likewise can be identified by using search engines to reveal locations where the email has been used on the Internet. Humans are creatures of habit and will use and reuse nicknames, descriptive screen names, or slight variations of these in their email addresses. For instance the person using [email protected] may also use [email protected]. Consider searching by everything prior to the @ symbol for additional leads. Websites like Email Finder, http://www.emailfinder.com/, can be useful at finding email address information on the Internet. My Email Address, http://my.email.address.is/, is a multiple email search engine that can help to identify an email address. Mail Tester, http://mailtester.com, allows the investigator to identify the MX (Mail transfer) records of the email address including the server that hosts the mail service. JigSaw, http://www.jigsaw.com/, is a business contact service that can also provide information on email addresses.

Searching blogs

Comments on blogs have become a regular source of complaint. Personal anonymous comments made on one of the tens of thousands of blogs that exist can be problematic to find. Searching through that many blogs can sometimes be a monumental task. Google is as always a good start for any searching. Many blogs allow for anonymous posting which can be a near dead end for an investigator. Some blogs may record poster's IP addresses, but this is only available by legal service to the blog owner or blogging site. There are some sites, although few, that actually record the poster’s IP address. This is not always visible in the browser. The investigator may have to look at the blog’s source code to identify the IP address. Blogs sometimes include the IP address in the blog source code but do not make it visible on the page. Investigators should check the source code for possible inclusion of the poster’s IP address (see Chapter 13 for further details on viewing source code).

As noted in Chapter 9, there are ways to conceal one’s IP address, which defeats this identifying technique. Again, be aware that some blog posters will reuse screen names on different blogs. They will also post similar information or use a catch phrase routinely in their postings. The screen name or these other user habits can become search engine queries, which may reveal more posts on different sites, which might lead to some piece of information that leads to the blogger’s identification. The following sites can be good information resources for the investigator to locate blog postings:

• Blogs.com, http://www.blogs.com/

• Blogdigger.com, http://www.blogdigger.com/index.html

• Blogsearchengine.com, http://www.blogsearchengine.com/

• Feedster.com, http://www.feedster.com/

• Google Blog Search, http://www.google.com/blogsearch

• Technorati.com, http://technorati.com/

• Yahoo.com, http://blog.search.yahoo.com

Professional communities

Professional social networking communities are another great source of information for the investigator. Persons using these sites generally are intending to make a good business or professional presentation. Much of the information presented is related to their education and previous employment. However, it is not unheard of to see partial dates of birth, telephone numbers, and email addresses. Additionally, the investigator can identify additional insight into the user’s account by reviewing groups that they belong to. Some users also feel compelled to provide their itineraries. These sites generally have a public profile and a member’s only accessible profile containing access to additional information. Information can be identified from the public profile as in the example of Figure 12.6. Additionally, information can also be viewed from a search engine’s cache result of the public profile page. However, more information is usually reserved for other social media site members. The investigator can login and see additional information about the site member. The investigator needs to be aware that the site might alert the user that someone has looked at their site and the user who reviewed the site. Undercover accounts used for this purpose should be consistent with the target’s background. The following are some common professional networking sites:

• Jigsaw.com, http://www.jigsaw.com/

• Linkedin.com, http://www.linkedin.com/

• Spoke.com, http://www.spoke.com/

• Ryze.com, http://www.ryze.com/

• Xing.com, http://www.xing.com/

• Zoominfo.com, http://www.zoominfo.com/

News searches

From an investigative purpose, news-related articles about target individuals and companies can be of significant benefit to an investigation. Searching Google as usual can provide a significant amount of information. Also consider Google and Bing’s news search engines (https://news.google.com/ and http://www.bing.com/news) There are several search sites the investigator can make use of that are dedicated to news-related information. Additionally, with today’s video popularity news is no longer just print news or blogs. Investigators need to consider searching sites like YouTube (a Google company). Below are some useful search sites for news:

• Newsvine.com, http://www.newsvine.com/

• Onlinenewspapers.com, http://www.onlinenewspapers.com/

• Reddit.com, http://www.reddit.com/

• Stumbleupon.com, http://www.stumbleupon.com/

• Techdirt.com, http://www.techdirt.com/

Video news

• ABC News, http://abcnews.go.com/

• Aljazeera, http://www.aljazeera.com/

• British Broadcasting Corporation, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/video_and_audio/

• Cable News Network, http://www.cnn.com/video/

• CBS News, http://www.cbsnews.com/

• Fox News, http://video.foxnews.com/

• LinkTV, http://www.linktv.org/

• NBC News, http://www.nbc.com/news-sports/

• Newsy, http://www.newsy.com/

• Public Broadcasting Corporation, http://www.pbs.org/search/

• Reuters News, http://www.reuters.com/news/video

• The Real News, http://therealnews.com/t2/

• USA Today, http://www.usatoday.com/media/latest/videos/news/

Conclusions

This chapter provided the investigator with useful Internet resources. We discussed the differences between search directories and search and metasearch engines. We noted that search engines are frequently the first choice in looking for information on individuals, companies, and telephone/cell numbers, and email address. We further provided a general investigative process which commences with search engine inquiries, then specific site searches, ending with biological search sites. Each of the provided websites can provide information that the investigator can use to further their investigation. The investigator can utilize the resources here and on the Internet to effectively identify and locate information on the targets as well as the victims in an investigation.

Further reading

1. 411.com—Official Site. (n.d.). 411.com—Official Site. Retrieved from <http://www.411.com>.

2. 42 Bing Search Engine Hacks. (n.d.). ivanwalsh.com. Retrieved from <www.ivanwalsh.com/google-tips/42-bing-search-engine-hacks/>.

3. ABCNews.com—Breaking News, Latest News & Top Video News. (n.d.). ABC News. Retrieved from <http://abcnews.go.com/>.

4. Adhikari, R. (2010, October 14). Facebook and Bing Do the Search Two-Step. TechNewsWorld: All Tech—All The Time. Retrieved from <http://www.technewsworld.com/rsstory/71036>.

5. Al Jazeera English—Live US, Europe, Middle East, Asia, Sports, Weather & Business News. (n.d.). Al Jazeera News. Retrieved from <http://www.aljazeera.com/>.

6. BBB Consumer and Business Reviews, Reports, Ratings, Complaints and Accredited Business Listings, U.S. (n.d.). Council of Better Business Bureaus. Retrieved from <www.bbb.org/us/>.

7. BBC News—One-minute World News. (n.d.). BBC—Homepage. Retrieved from <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/video_and_audio/>.

8. Bing. (n.d.). Bing. Retrieved from <http://bing.com>.

9. Bing Advanced Search Keywords. (n.d.). Online Help. Retrieved from <http://onlinehelp.microsoft.com/en-us/bing/ff808421.aspx>.

10. Blachman, N., & Peek, J. (n.d.). Google Search Operators—Google Guide. Interactive Online Google Tutorial and References—Google Guide. Retrieved from <http://www.googleguide.com/advanced_operators_reference.html>.

11. Blogdigger: Blog Search Engine—Search Blogs. (n.d.). Blogdigger. Retrieved from <http://www.blogdigger.com/index.html>.

12. Blogs.com. (n.d.). Blogs.com. Retrieved from <http://www.blogs.com>.

13. Blog Search Engine. (n.d.). Blog Search Engine. Retrieved from <www.blogsearchengine.com/>.

14. BOP: Inmate Locator Main Page. (n.d.). BOP: Federal Bureau of Prisons Web Site. Retrieved from <http://www.bop.gov/iloc2/LocateInmate.jsp>.

15. Breaking News Headlines: Business, Entertainment & World News—CBS News. (n.d.). CBS News. Retrieved from <http://www.cbsnews.com/>.

16. Business Profiles and Company Information: ZoomInfo.com. (n.d.). Business Profiles and Company Information: ZoomInfo.com. Retrieved from <http://www.zoominfo.com>.

17. Cached Link—Search Help. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <https://support.google.com/websearch/answer/1687222?hl=en&p=cached>.

18. Charity Navigator—America’s Largest Charity Evaluator. (n.d.). Charity Navigator. Retrieved from <http://www.charitynavigator.org/>.

19. Clusty.com—Clusty Search Engine. (n.d.). Clusty.com—Clusty Search Engine. Retrieved from <http://clusty.com>.

20. Companies House. (n.d.). Companies House. Retrieved from <http://www.companieshouse.gov.uk/>.

21. comScore Releases June 2013 US Search Engine Rankings—comScore, Inc. (2013). Analytics for a Digital World—comScore, Inc. Retrieved from <http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Press_Releases>.

22. Connecting You to the World: Link TV. (n.d.). Link TV. Retrieved from <http://www.linktv.org/>.

23. CNN Video—Breaking News Videos from CNN.com. (n.d.). CNN.com—Breaking News, US, World, Weather, Entertainment & Video News. Retrieved from <http://www.cnn.com/video/>.

24. Do a Charity Check Before You Donate. (n.d.). CharityCheck101.org. Retrieved from <http://charitycheck101.org/>.

25. Dogpile Web Search. (n.d.). Dogpile Web Search. Retrieved from <www.dogpile.com>.

26. EBR—European Company Information Online. (n.d.). EBR—European Company Information Online. Retrieved from <http://www.ebr.org/section/1/index.html>.

27. Email Search—Email Address Search—Find Email Addresses. (n.d.). My.Email.Address.Is. Retrieved from <my.email.address.is/>.

28. Email Search & Reverse Email Lookup. (n.d.). emailfinder.com. Retrieved from <www.emailfinder.com/>.

29. EO Select Check. (n.d.). Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved from <http://www.irs.gov/Charities-&-Non-Profits/Exempt-Organizations-Select-Check>.

30. Explore More. Web pages, Photos, and Videos: StumbleUpon.com. (n.d.). StumbleUpon.com. Retrieved from <http://www.stumbleupon.com/>.

31. FeedsterSearch—Home. (n.d.). FeedsterSearch—Home. Retrieved from <http://www.feedster.com>.

32. Find (Almost) Anybody’s Email Address|Distilled. (n.d.). Distilled: Online Marketing, PPC & SEO Agency in London, Seattle & NYC. Retrieved from <http://www.distilled.net/blog/miscellaneous/find-almost-anybodys-email-address>.

33. Fone Finder Query Form. (n.d.). Fonefinder.Net:Primeris, Inc. Retrieved from <fonefinder.net/>.

34. Fox News Video. (n.d.). Fox News. Retrieved from <http://video.foxnews.com/>.

35. Free People Finder and Company Search: SearchBug. (n.d.). Free People Finder and Company Search. Retrieved from <http://www.searchbug.com/>.

36. Free People Search Engine: ZabaSearch. (n.d.). Free People Search Engine; ZabaSearch. Retrieved from <http://www.zabasearch.com>.

37. Free Public Records: Search the Original Resource Worldwide. (n.d.) Free Public Records: Search the Original Resource Worldwide. Retrieved from <http://www.searchsystems.net>.

38. Google. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <http://www.google.com>.

39. Google Advanced Search. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <http://www.google.com/advanced_search>.

40. Google Blog Search. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <http://www.google.com/blogsearch>.

41. Google News. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <https://news.google.com/>.

42. GuideStar Nonprofit Reports and Forms 990 for Donors, Grantmakers and Businesses. (n.d.). GuideStar. Retrieved from <http://www.guidestar.org/>.

43. Hagedorn, E. (n.d.). Newsy: Multisource Video News. Retrieved from <http://www.newsy.com/>.

44. Haynal, R. (2013, March 1). Cached Issues. Russ Haynal—Home Page. Retrieved from <http://navigators.com/cached.html>.

45. Home—Canadian BBB. (n.d.). Canadian Council of Better Business Bureaus. Retrieved from <www.bbb.org/canada/>.

46. Hoover’s Company Information. (n.d.). Hoover’s Company Information, Industry Information, Lists. Retrieved from <http://www.hoovers.com>.

47. lineUSA. (n.d.). Videos, Photos—USATODAY.com. USA TODAY: Latest World and US News—USATODAY.com. Retrieved from <http://www.usatoday.com/media/latest/vide>.

48. IRBsearch. (n.d.). IRBsearch: Information Exclusively for Investigative Professionals. Retrieved from <http://www.irbsearch.com>.

49. Jarboe, G. (2003, October 15). A “Fireside Chat” with Google’s Sergey Brin. Search Engine Watch (#SEW). Retrieved from <http://searchenginewatch.com/article/2064259/A-Fireside-Chat-with-Googles-Sergey-Brin>.

50. Jigsaw Business Contact Directory of Business Contacts and Company Information. (n.d.). data.com. Retrieved from <www.jigsaw.com/>.

51. Kaushal, N. (2011, October 24). Now Bing Powers Yahoo Organic Search. SearchNewz, Search Engine News. Retrieved from <http://www.searchnewz.com/now-bing-powers-yahoo-organic-search-2011-10>.

52. Koch, P., & Koch, S. (2007). Search Engine Tutorial by Pandia—a Free Guide to Web Searching. Pandia Search and Social. Retrieved from <http://www.pandia.com/goalgetter/index.html>.

53. MailTester.com. (n.d.). MailTester.com. Retrieved from <http://mailtester.com>.

54. Manta. (n.d.). Manta—Big finds from Small Businesses. Retrieved from <http://www.manta.com>.

55. Microsoft‘s New Search at Bing.com Helps People Make Better Decisions. (n.d.). Microsoft Corporation. Retrieved from <http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/news/press/2009/may09/05-28NewSearchPR.aspx>.

56. National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved from <http://www.archives.gov/>.

57. NBC.com—News & Sports—NBC Official Site. (n.d.). NBC.com. Retrieved from <http://www.nbc.com/news-sports/>.

58. Newsvine. (n.d.). Newsvine. Retrieved from <http://www.newsvine.com/>.

59. NOZA 990-PF Database Listing. (n.d.). Grantsmart.com. Retrieved from <http://www.grantsmart.com/>.

60. NOZA—Charitable Donations Database and Prospect Research. (n.d.). NOZA. Retrieved from <https://www.nozasearch.com/>.

61. Our History in Depth—Company—Google. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <http://www.google.com/about/company/history>.

62. Paczkowski, J. (2009, May 28). Microsoft Bing: The full press release—John Paczkowski—D7—AllThingsD. AllThingsD. Retrieved from <http://allthingsd.com/20090528/micro>.

63. Pandia Search and Social. (n.d.). Pandia Search and Social. Retrieved from <http://www.pandia.com>.

64. Perez, S. (2008, March 31). The Best Tools for Visualization. ReadWrite. Retrieved from <http://readwrite.com/2008/03/13/the_best_tools_for_visualization>.

65. Peterson, T. (2012, May 10). Microsoft Revamps Bing with Social Sidebar|Adweek. Adweek—Breaking News in Advertising, Media and Technology. Retrieved from <http://www.adweek.com/news/technology/microsoft-revamps-bing-social-sidebar-140302>.

66. Pipl—People Search. (n.d.). Pipl—People Search. Retrieved from www.pipl.com.

67. Phone Number and Reverse Phone Search. (n.d.). PhoneNumber.com. Retrieved from <PhoneNumber.com>.

68. Public Records. (n.d.). Public Records. Retrieved from <http://www.brbpub.com/>.

69. Pyle, C. H., & WarIsACrime.org. (n.d.). The Real News Network—Independent News, Blogs and Editorials. Retrieved from <http://therealnews.com/t2/>.

70. Rapportive. (n.d.). Rapportive. Retrieved from <http://rapportive.com/>.

71. Recommendations on Net Searching. (n.d.). Pandia Search and Social. Retrieved from <http://www.pandia.com/goalgetter/recommendations.html>.

72. Reddit: the Front Page of the Internet. (n.d.). Reddit. Retrieved from <http://www.reddit.com/>.

73. Registrars—Corporations Canada. (n.d.). Corporations Canada. Retrieved from <www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cd-dgc.nsf/eng/cs01134.html>.

74. Ryze—the Original Social Network for Business. (n.d.). Ryze. Retrieved from <http://www.ryze.com/>.

75. Search. (n.d.). PBS: Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved from <http://www.pbs.org/search/>.

76. SearchBug. Retrieved from <http://www.searchbug.com>.

77. Search Business Names Register. (n.d.). Australian Security and Investment Commission. Retrieved from <https://connectonline.asic.gov.au/RegistrySearch/faces/landing/bn/SearchBnRegisters.jspx?_adf.ctrl-state=t5t9t1hry_13>.

78. Search Historical SEC EDGAR Archives. (n.d.). US Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved from <http://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/srch-edgar?>.

79. SEC Info. (n.d.) SEC Info—the Best EDGAR Online Database of Securities and Exchange Commission Filings & IPOs. Retrieved from <http://www.secinfo.com/>.

80. SEO Keyword Graph Visualization|SEO Browser—TouchGraph.com. (n.d.). TouchGraph.com. Retrieved from <http://www.touchgraph.com/TGGoogleBrowser.html>.

81. Spoke: Discover Relevant Business Information. (n.d.). Spoke. Retrieved from <http://www.spoke.com/>.

82. Techdirt. (n.d.). Techdirt. Retrieved from <http://www.techdirt.com/>.

83. Technorati. (n.d.). Technorati, Inc. Retrieved from <technorati.com/>.

84. Thousands of Online Newspapers on the Web: World Newspaper Directory: Listed on OnlineNewspapers.com. (n.d.) Online Newspapers on the Web. Retrieved from <http://www.onlinenewspapers.com/>.

85. Top Stories—Bing News. (n.d.). Bing. Retrieved from <http://www.bing.com/news>.

86. United States Department of Justice National Sex Offender Public Website. (n.d.). United States Department of Justice National Sex Offender Public Website. Retrieved from <http://www.nsopw.gov/>.

87. Untangling the Web: An Introduction to Internet Research. (2007). Washington, DC: National City Agency, Center for Digital Content.

88. U.S. Department of Labor—Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS)—Online Public Disclosure Room: Union Reports and Collective Bargaining Agreements. (n.d.). United States Department of Labor. Retrieved from <http://www.dol.gov/olms/regs/compliance/rrlo/lmrda.htm>.

89. Video—Top News Videos, Business & Entertainment Videos: Reuters.com. (n.d.). Business & Financial News, Breaking US & International News: Reuters.com. Retrieved from <http://www.reuters.com/news/video>.

90. WebFetch. (n.d.). WebFetch. Retrieved from <www.webfetch.com>.

91. World’s Largest Professional Network: LinkedIn. (n.d.). LinkedIn. Retrieved from <http://www.linkedin.com/>.

92. Worldwide Directory of Public Companies. (n.d.). CreditRiskMonitor—Search for a Public Company. Retrieved from <http://crmz.com/directory/>.

93. XING—Das professionelle Netzwerk. (n.d.). XING. Retrieved from <http://www.xing.com/>.

94. Yahoo!. (n.d.). Yahoo!. Retrieved from <http://www.yahoo.com>.

95. Yahoo! Blog Search. (n.d.). Yahoo! Blog Search. Retrieved from <http://blog.search.yahoo.com>.

96. Yahoo! Directory. (n.d.). Yahoo! Directory. Retrieved from <http://dir.yahoo.com/>.

97. YouTube. (n.d.). YouTube. Retrieved from <https://www.youtube.com/>.

98. Zetter, K. (2013, May 8). Use These Secret NSA Google Search Tips to Become Your Own Spy Agency. Threat Level: wired.com. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2013/05/nsa-manual-on-hacking-internet/>.

1Yahoo! Directory (http://dir.yahoo.com/) is not the same as Yahoo! (http://www.yahoo.com). If one goes to the later and enters a search term, a search engine will be used to produce the results.

2Not all countries have registered sex offenders. Additionally, those that do may not always make the data available outside of the law enforcement community.

3In the United States, many of the state correctional systems also have online access to names in their inmate and/or parolee databases. Other countries restrict this information but some provide it online. Do a Google search to locate if an online inmate database exists in the country of interest.