Investigating Social Networking Sites

This chapter is intended to provide investigators an understanding of social networking and their significance to investigations. Social networking has become a large part of the investigator’s Internet resources for locating and identifying useful information. Social media sites can also provide the investigator with a large amount of data on the target’s behavior that can tend to show their culpability or motivation in illegal activity. Additionally, metadata present in some social media setting can provide location information. This data can be important to place a subject in a particular geographic area or may lead to their apprehension. Clearly, social media information has changed the investigative landscape and is now considered one of the initial steps in any investigation.

Keywords

Social networking; social media; Facebook; Twitter; Plaxo; Myspace; Spokeo; LinkedIn; Spoke; CCSIP; Electronic Freedom Foundation; FBI; Google; Yahoo; Bing; Creepy; Flickr; yoName; Bebo; Myspace visualizer; Bebo visualizer; Lococitato

There’s a danger in the Internet and social media. The notion that information is enough, that more and more information is enough, that you don’t have to think, you just have to get more information - gets very dangerous.

Edward de Bono (physician, author, inventor, and consultant)

Social networking’s impact on legal systems

Social network use among the public has reached the point where it can no longer be ignored as a passing fad, or considered a high-tech crimes investigation specialty. Detectives, patrol, intel, and gang officers, administrators, private and corporate investigators, prosecutors and corporate counsel need to know who’s online, what kinds of crimes they’re committing, what evidence they’re leaving and, where it can be found. More importantly from a legal standpoint is obtaining online evidence in a manner so that it can be used to win convictions or in litigation. Why is it that we need to care about social networking sites? The answer is that is where the people are and it is where the criminals will go to victimize them. Let’s look at some social networking statistics for some perspective on the issue. GlobalWebIndex reported that Facebook has 701 million active users, with Google Plus and Twitter at 359 and 297 million active users, respectively. (Watkins & Presse, 2013) Seventy-two percent of online US adults use social networking sites. (Brenner & Smith, 2013) Surely, the sheer number of users is large and obviously has an impact. But that is only part of the concern. Specifically, how much are these users on social media and how much data is being generated as result? Smith (2013) provides clues to these questions, with the following user stats for Facebook and Twitter:

• Average number of monthly posts per Facebook user page: 36

• Average number of friends per Facebook user: 141.5

• Average time spent per Facebook visit: 20 minutes

• Average time spent on Facebook per user per month: 8.3 hours

• Average followers per Twitter user: 208

These stats represent another investigative concern, specifically the number of profiles a target may have on various social networking sites. Having more than one profile on a social networking site can occur as well as having profiles on a number of different sites. A social networking investigation can involve a lot of data particularly if the target and those associated with the target (the victim, witnesses, and associated targets) have more than one social media profile.

If the target or victim is a corporation the investigator needs to be aware that most corporations will have more than one social networking site account. Owyang (2011) details a 2012 Altimeter Group survey, which received responses from 140 companies with over 1,000 employees. The survey found that the respondent companies averaged 178 official social networking accounts per company. This includes 39.2 Twitter accounts, 31.9 Blogs, 29.9 Facebook accounts, 28 LinkedIn accounts, and many others on various forums, message, image, and video sites. The point here is a social media investigation, without focus, without a plan, could easily become an Odyssey with no clear accomplishment.

Social networking investigations are not without other challenges. Many officers do not know how to navigate the myriad of social networking sites. To compound the investigative issues many government agencies have restricted access to those sites out of fear of what employees will say or do online. To address these issues, they need to understand effective investigative techniques as well as a suitable policy. Receiving detailed social network training becomes very critical in today’s Internet-connected society.

Law enforcement, social media, and the news

In the last few years articles have claimed to expose a new offensive by the FBI to invade the privacy of people on the Internet. (McCullagh, 2010; Parrack, 2010) The Electronic Freedom Foundation (EFF) filed suit, along with the Berkeley Law School, against various Federal agencies trying to expose their investigative use of social networking. Using a Freedom of Information Act, the EFF obtained their smoking gun. They obtained a US Department of Justice PowerPoint presentation discussing the general issues surrounding social networking and how to go about using it effectively as an investigative tool. Nothing earth shattering, but apparently many in the press seemed to be surprised that the FBI was doing their job. The EFF was so impressed with the revelation that they have made their own webpage “FOIA: Social Networking Monitoring” just to track their progress at exposing law enforcements’ use of social networking to the world.

Social networking has changed many things when it comes to our online lives. Immediate postings of user activities, locations, and the divulging of individual’s feelings are common. Everyone realizes that all of this is posted for the world to see otherwise they would not be doing it. We are becoming a bunch of Internet exhibitionists. With that exposure comes those that would take advantage of our openness. Criminals tend to congregate where victims increasingly gather. Law enforcement is starting to recognize this and is also gathering in the social networking sphere. So with online crime comes policing of the Internet. So, the police, and the FBI, will go where the criminals go. Ergo, the FBI is working undercover on Facebook to catch criminals and terrorist. This is shocking to only those blind to how law enforcement functions.

Social networking’s impact is not just as new undercover tool. On February 18, 2010, Joe Stack, flew his plane into a federal building as both a suicide and antigovernment gesture (Brick, 2010). The story quickly made national headlines. Social media made private citizens into scene reporters telling the world in real time about events as they unfolded. Traditional news media gathered this information and reportedly after confirming it, included it their own coverage of the incident (Gonzalez, 2010).

Austin Police Chief Art Acevedo, apparently unhappy that information was flowing in this matter retorted “There’s a lot of speculation. I can tell you right now that those reports are inaccurate and it is irresponsible journalism to put out information that is not confirmed through law enforcement.” YNN News Channel 8, agreed in their commentary but correctly observed “But law enforcement needs to keep up with the speed of citizen journalism using social media” (Gonzalez, 2010).

We don’t know for sure what context the Chief’s single quote was regarding, but it is a little arrogant to think that his department is the only source for correct information. Social media has changed many things and citizens are regularly using it to report news as well as track crimes. The fact that a person can live stream information from an incident like that changes how we receive our news and how journalists are viewing their position in the reporting of that news. Law enforcement is going to have to adapt to the changing speed of the information flow. Private citizen’s use of social media necessitates that law enforcement respond more quickly. Law enforcement public information officers will also need to learn to track social media at the scene of an incident and respond to the information more timely. Investigators will need to start tracking this information to identify leads related to an incident. Social media has changed dramatically how law enforcement will need to respond to incidents and the news media in the future. The question is how quickly law enforcement can adapt to the changing social media landscape.

The Boston Marathon Bombing is an example of both advantages and disadvantages of law enforcement’s using social media to solve crimes. The FBI posted photos of Suspect 1 and Suspect 2 from surveillance footage to social media, seeking the public’s assistance in identifying the individuals in the photos. Unfortunately, the public erroneously identified one of the subjects as an innocent bystander, requiring a quick correction by law enforcement. Ultimately, law enforcement obtained a clearer picture and was able to identify the correct suspect through their YouTube page (Presutti, 2013).

Many investigators are probably thinking that these kinds of social media events only happen to big cities like Austin and Boston. This is simply not true and the below example should be a sobering warning that law enforcement does have to “keep up with the speed” of its citizen’s use of social media.

Social media in small town USA

Steubenville, OH, birth place of Dean Martin and Jimmie the Greek, was founded in 1797, along the Ohio River in Jefferson County. During its peak in the 1940s–60s, it was popularly known as “Little Chicago,” a nickname evoked, not only for its prolific industry and downtown bustle, but also for its reputation for crime, gambling, and corruption (Forbes, 2013).

However, in the twenty-first century, Steubenville ranked as Ohio’s #101 largest city, with a population of 18,659 (USA.com, 2013). Its police force has 38 officers and 3 dispatchers (The Intelligencer and Wheeling News-Register, 2013). Jefferson County, where it is located has a population of 69,709 and covers 408 square miles. (State and County QuickFacts, 2013) Jefferson County’s Sheriff’s Office size is commensurate with the size of the population is serves. Forbes considers Steubenville’s Metro population, encompassing nearby Wheeling, West Virginia at 123,200. By any standard Steubenville is a not large city, not even comparable to Austin or Boston. Nevertheless, this did not stop Steubenville from finding itself in the social media cross-hairs, the result of a brutal crime committed by some of Jefferson County’s youngest citizens.

On August 11, 2012, teenagers from several nearby high schools meet for an end-of-summer party, which also kicked off the coming football season. High school football is a big event in this area. As too frequently occurs the party also involved alcohol. Teenage party goers used social media to announce the party. However, it did not end there. During the evening a teenage girl, unconscious from drinking was sexually assaulted by several members of Steubenville’s Big Reds football team. Social media posts, videos and photographs started circulating, documenting that the unconscious girl had been sexually assaulted over several hours, while some watched the crime occur without intervening (Dissell, 2012).

The victim, because of her state, did not initially recall what happened to her that night. However, as the information supported by the social media posts came to light, she and her parents realized what had occurred. They took a flash drive full of social media postings indicating that the victim had been assaulted to the police. Police seized cell phones of the teenage suspects and found more digital traces that corroborated the victim’s story. Two teenager offenders were arrested (Macur and Schweber, 2012).

However, it did not end there. The citizens began taking sides and expressing their views via social media. The story got the attention of Alexandria Goddard, a local web analyst with a national crime blog, who started writing about the case in her blog. This further fueled the discussion, particularly how could only two individuals be arrested for this crime (Macur and Schweber, 2012). From there it took on a life of its own, gaining worldwide attention, including a cell of the hacktivist collective Anonymous, who promptly inserted itself into the social media circus by posting its own information (Abrad-Santos, 2013).

The two juveniles were convicted of the sexual assault and sentenced. However, it did not end there. Two additional teenagers, ages 15 and 16, were charged with intimidation over social media posts they allegedly made concerning the victim. The local sheriff noted after those arrests “And I can assure you we’ve been monitoring Twitter for 24 hours and continue to. If there’s anybody else there crosses a line and makes a death threat, they’re going to have to face the consequences.” Ohio Attorney General Mike Devine, whose office handled the locally sensitive case noted: “People who want to continue to victimize this victim, to threaten her, we’re going to deal with them and we’re going after them. We don’t care if they’re juveniles or whether they’re adults. Enough is enough” (Pearson, Carter, & Brady, 2013).

One can only imagine the investigative resources that this case required. Would your department be prepared to handle this kind of case, where social media not only provides evidence but fuels intense feelings in not only your community but the world?

Social media around the world

Social media is not a United States-centric problem. Law enforcement investigators around the world are grappling with the social media associated issues. Recent studies in Europe have identified similar issues regarding the complexity of social media.

Denef, Bayerl, and Kaptein (2012) examined law enforcement’s use of social media based on interviews and focus groups of European law enforcement experts in 10 countries. Their report found three cross-European variations: (1) implementation strategies, (2) media selection/integration, and (3) communication with the public. They found that police agencies adopt social media as needed, some from the bottom-up, officers utilizing social media without restrictions and others from the top-down.

Top-down agencies create general guidelines before deploying the social media resources. They also identified three common social media deployment methods, selective, centralized, and modular. The selective approach meant the agency picked the most popular services to follow and use. The centralized approach utilized their agency website as the primary central location for social media. The modular approach identified each social media tool with an individual strategy.

Additional recent European studies have identified that acceptable use of social media in law enforcement differed by country and the type of job an officer was assigned (Bayerl, 2012). To aid in the understanding and deployment of social media in use by policing agencies in Europe the European Commission has published the “Best Practice in Police Social Media Adaptation.” This best practices guide identified and detailed the following categories as the principles to use by police when adopting social media:

1. Social media as a source of criminal information

2. Having a voice in social media

3. Social media to push information

4. Social media to leverage “crowd” the wisdom

5. Social media to interact with the public

6. Social media for community policing

7. Social media to show the human side of policing

The Demos ThinkTank, a British cross-party organization, published a paper focusing on an analysis of Twitter posting between the Metropolitan Police and the public following the murder of British Army soldier, Drummer (Private) Lee Rigby (Bartlett & Miller, 2013). Of interest to the investigator is the detailed analysis of the Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT) that the police received through a single social tool. The analysts extracted from the @metpoliceUK’s twitter account 19,344 tweets over the period of May 17–23, 2013. The study came up with recommendations which should come as no surprise to law enforcement or corporate investigators familiar with the power of social media. Dealing with social media is no longer a thing for investigators to avoid but a requirement to engage in and understand. The recommendations were:

Social media evidence in the courts

Worldwide social networking use has increased, compelling more courts to consider and accept Internet-based evidence. However, authentication as with any evidence is still required. The problem becomes one of Internet evidence documentation in a manner that will be acceptable to the courts. Online or Internet evidence is digital evidence, with the same concerns as any evidence collected from a computer. The digital forensic field has for years followed court accepted methodologies for getting electronically stored information (ESI) admitted or accepted as evidence. The process includes the proper collection, preservation, and presentation. It is done so through logging examiners and/or investigator’s actions, collecting the evidence, date and time stamping it, and hashing the saved digital files. Lastly in the process is the presentation of the collected Internet evidence in a manner usable by the attorneys and the courts. In Chapter 4, we discussed Lorraine v. Markel Am. Ins. Com, 241 F.R.D. 534, 538 (D. Md., 2007) and other legal issues related to online evidence. Those issues and concerns are valid for all online ESI, regardless of whether it is found on a social networking site or a website. Courts will no doubt continue to wrestle with online ESI, particularly as social networking sites are increasing in prevalence and usage.

Starting a social networking site investigation

Social networking sites are different than most websites. This is mainly due to these sites’ content driven environment. A website in general provides text, images and downloads of documents or other material stored on the site for later viewing. They provide a means to communicate information to the person viewing the site. Social media sites, however, provide a means for the members to communicate among themselves. This information sharing can include traditional website text, images, and downloads. However, social networking sites focus on sharing information in real time. This focus is accomplished through messaging, email among the users, and user security/privacy features limiting sharing to only approved content and/or to specified users. This real time, and the sharing between multiple user's components, means investigators have a much larger task in documenting social networking site data. The task requires that investigative planning becomes far more important than simply snapshotting a webpage and downloading the source code.

The other significant preplanning factor in social networking collection and documentation is the fact that today most individuals do not have one social networking account, but several, across different social networking platforms. Without a directed collection and investigation plan the investigator could easily miss relevant information or simply go on collecting data without a sense of need to support the ongoing investigation.

Planning

We can start the planning by identifying the basics (who, what, and where) to help us determine the information we are looking for and how to collect it.

1. What is the target’s real name? This sometimes is not known and we may have to move to the next step.

2. What is the target’s usernames?

3. Research the name through search engines and social media site search engines. Get a clear picture of the location that are to be included in the plan.

4. What is the information that we need to collect in the case?

a. Are we simply looking to identify the user behind the account?

b. Are we attempting to locate information about the user’s activities (online or offline), which can be images, comments, posts, comments, etc.?

5. Where are the sites that the target uses?

6. Were the sites located geographically, are they in the same country as the investigator? Check with your prosecutor of counsel as to the collection methods available for the investigator’s use in the case.

Answers to these questions will dictate the manner in which the investigator accesses and collects online ESI. Collection of any online ESI from a social networking site requires preplanning of the process and identifying the proper and authorized access method. The following are the four primary methods to access social networking sites in order to collect online ESI:

1. Available public information: This is the easiest to prepare for and collect. The available public information is content that the user (or the social networking site) allows to be seen by anyone viewing the user’s page on the site. Collection and documentation planning begins with identifying the user’s site, documenting the information with the tools we have described previously in the book and preparing collection reports.

2. Available “Approved Friend or Associate Information”: Collecting information on the social networking site as an approved or friend or associate can be accomplished in two manners:

a. A cooperating witness, who is a friend/associate allows the investigator to use their profile to collect content that the target user has shared or allowed them to view. This can be short-term access, limited to content that exists at the time the cooperating witness granted consent or it can be continuing which is an undercover operation involving an identity takeover (see Chapter 10). An identity takeover requires significant investment in the investigation by the investigator and his agency/company. The problem with consent is it can be revoked prior to the online ESI collection is completed.

b. The second option requires the target’s acceptance of the investigator as a friend/associate. This obviously requires direct communication with the target to have them allow you access. Usually this is with an undercover account and requires all the basic background required to produce an undercover persona as we have described previously. This option is much more involved than even the identity takeover and is certainly more difficult and requires more preparation than collecting public information. Undercover operations again require a significant investment in the investigation by the investigator and his agency/company.

3. Available private information: This collection is possible with the target’s cooperation. The investigator is given access by the target through there username and password and collects the available information through the means we have discussed previously and throughout this chapter. Again, the problem with consent is it can be revoked prior to when the online ESI collection is completed.

4. Available information through legal service: This option requires that there be sufficient legal authority to require the social networking site to provide all the available information under the target’s account directly from the social networking site's legal compliance department. Online ESI that was collected through options 1–3, as well as other investigative procedures may provide the legal basis (probable cause, etc.) to justify access via compulsory legal process (see Chapter 4). The legal service method frequently has the added benefit of providing details, such as IP addresses or global positioning information at the time the target user accessed and/or posted to their account. Such information is usually not available under options 1–3.

Preplanning the social networking investigation is an important step in a successful Internet investigation. The investigator that follows these concepts will be better prepared and have a more successful social networking collection and investigation.

Social networking sites commonalities

Social networking sites have some investigative similarities that need to be discussed. As we know social media today, each member of a particular site must have a valid login to access the site’s functions. Most allow some access by nonmembers but the online ESI provided may not be useful for the investigation. Generally the sites require a valid email account. The user has to provide a username (on some sites this data needs to be real, others don’t care). Commonly a validation feature includes a telephone number (generally a cell phone) that can be used to verify the user is a live person, the information is real, and/or later account access is legitimate. Some accounts require an email account to be connected with the user’s account. Also, many social networking sites can be interconnected. A Facebook user’s account is connected to Twitter, Twitter connected to LinkedIn, etc.

Social networking sites all have a profile or user biography, all of which is self-identified information supplied by the account holder. They may contain the account holder’s picture, a place to post messages to and from the account holder. Many sites also have places to post images or videos. Some sites, but not all, even leave the metadata in multimedia files, (think latitude and longitude if the camera collects this information). The profile may have a credit card associated with it to pay for membership or to gain additional features from the site. Additionally, most sites now offer access through mobile phones. All of this information, and the Internet Protocol addresses used to access the site, are available through legal service to the social networking site (Look to the ISP list maintained by SEARCH http://search.org/programs/hightech/isp/) for these contacts. The types of information maintained by the social networking sites varies from site to site. Additionally, the duration online ESI is maintained varies.

The top social networking sites

Every social networking site is different. The sites are all coded differently and each has their own method of user authentication. This make each unique and requires an individual approach to investigating the site. Searching for users can be done using the site’s search function. Often through using one of the big three search engines, Google, Bing, and Yahoo can guide the investigator to the user they are interested in better than the site’s own internal search function. There are other search tools that also can assist the investigator when looking for a target. Many of these search sites are specific to a particular social networking site and have a habit of coming and going. The investigator needs to be aware that these sites may also become ineffective due to changes that the social networking site makes to the site’s infrastructure. It has to be remembered though that the target may not be using a real name or only a moniker on the site and having these details can improve the accuracy of the search when looking for the target.

The top three social networking sites have changed over the years. Facebook, with its 1 billion plus user accounts has stayed on top for some time. It wasn’t that long ago in social networking history that MySpace was the big dog on the block and it still has a large following. Twitter with its minimalistic data posting ability has become a phenomenon that most would not have guessed. Each of these sites contains a large amount of data on its users and can easily be used in an investigation. A relative newcomer on the block is Google+. It has gained in popularity very quickly and has found its way to the top of the list. “As of July 2013, five of the ten biggest social networks in the world come from China: QQ, Qzone, RenRen, Youku Tudou, and Sina Weibo.” (Balolong, 2013) Clearly social networking has changed how many people in the world approach the Internet.

Any case the investigator has today can be supplemented with social networking site data. The social networking site information can be used as direct evidence. Or the information can be used as intelligence information as to whom the target’s friends are and what they have been doing recently. It can also tend to provide the general attitude of the social media user, determine political affiliation, and determine if the user is anarchist. The sites can also tend to tell the investigator that the target is just a normal person posting information for their family and friends. The information can assist the investigator in profiling the targets thoughts, behaviors, and actions as they relate to the investigation. Overlooking social media in today’s environment will limit the investigator’s understanding of the facts of the case and cloud their investigative situational awareness.

The investigator needs to remember that access to a social media site needs the proper legal authority. If the user has public information it is fair game. They posted the information for everyone to see. However, if their social networking profile has information marked by the users as private, or available only to the “friends” or restricted users, the investigator cannot simply befriend them and gain access. Investigators need to consult their legal authority and consider the current case law governing access to the data before they proceed with the social media investigation.

Examining social networking sites

As with any webpage, we can use a browser to locate content in the profile area, postings, images, etc. which is useful investigative information. Additionally, just like any webpage we can review the HTML code. However, viewing HTML coding on social networking sites does not reveal hidden comment or information generated by the user. This code is from the social networking site. Viewing and searching HTML code on some social networking sites can provide a different method to quickly locate investigative information. It can be faster to search and read text than waiting for a browser to load graphics and other extraneous information. Additionally, there are tools specific to certain social networking sites which allow data to be captured, analyzed, and/or presented in a manner that makes it much easier for the investigator to process. The following is a review of the major social networking sites and methods for investigating them.

Facebook’s stated mission “…is to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected” (Facebook, n.d.). As an online directory started in 2004, Facebook gives people a way to connect with individuals they know, went to school with, share common interests, and more. As we have previously noted it’s currently the most popular social networking site in existence, with over one billion users.

Examining Facebook

It would seem that identifying a Facebook user is as simple as reading the name reflected on a post. However, that text name may not always be the name used for the account profile uniform resource locator (URL). For instance, if the user has a vanity name, the account will have the vanity name in the profile URL. Later searching by text name, particularly if it is common, can produce numerous profiles before the correction profile is found, if ever. The best way to identify the account associated with a post is to hoover over it with your mouse, which will reveal the Friend’s profile page, which can be written down. Documenting the address can also be accomplished by right clicking the “Friend” name, selecting “Copy Link Address,” and pasting the address into a text document.

Facebook is the one site which can reveal useful information by viewing the page’s HTML code. Login into Facebook and proceed to the user’s page of interest. Once on the profile, examine the source code via your particular browser’s option as we described in Chapter 13 (With Internet Explorer go to “View” and select “Source.” In Chrome go to the settings button and select “Tools” and then “View Source). Opened in notepad will be the HTML source code for that individual page. The investigator can then use their browser’s search function to look for certain artifacts of possible investigative use. Here are some useful ones:

• Searching for ““user”:” will find the Facebook user’s ID number.

• Searching for “URL=/” and “title id=“pageTitle”” will find the Facebook user’s name for the account.

• Searching for a friend’s page can be found by searching the source code for the term“?hc_location=timeline.” In the source code at each location the term is found the investigator will find a “friend” listed on the page.

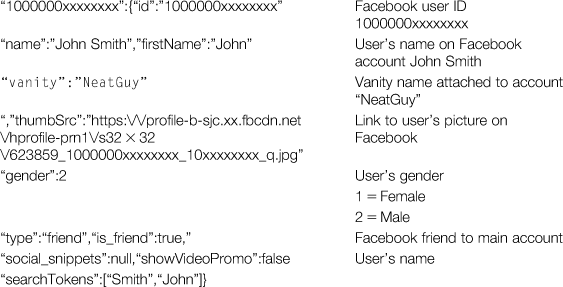

• Searching ““id”:” will help locate a stream of data looking like this:

“1000000xxxxxxxx”:{“id”:“1000000xxxxxxxx”,“name”:“John Smith”,“firstName”:“John”,“vanity”:“noletide”,“thumbSrc”:“https://profile-b-sjc.xx.fbcdn.net/hprofile-prn1/s32×32/623859_1000000xxxxxxxx_10xxxxxxxx_q.jpg”,“uri”:“https://www.facebook.com/noletide”,“gender”:2,“type”:“friend”,“is_friend”:true,“social_snippets”:null,“showVideoPromo”:false,“searchTokens”:[“Smith”,“John”]}

This data stream translates as follows:

Internet tools for understanding a Facebook target

There are numerous marketing tools for obtaining information on a Facebook account. There are a few caveats though. These sites, like many Internet resources require you to set up an account with them. Additionally, some tools will not function properly if the user has placed privacy restrictions on their account. With these caveats in mind, here are links to a few such tools:

• Facebook Fan Page Analytics http://simplymeasured.com/freebies/facebook-fan-page-analytics

• Likealyser, http://likealyzer.com/

• Statilizer http://statilizer.com/

Network overview, discovery and exploration in excel

NodeXL is an Excel spreadsheet template that provides the investigator the ability to analyze certain social networking sites, including Facebook. NodeXL was not developed with the investigator in mind but it is certainly a tool that is easily adopted for investigative use. It actively worked as an open source community project and its main page is hosted on Codeplex.com. NodeXL is a project from the Social Media Research Foundation and is a collaborative effort among several organizations including Microsoft Research. Its investigative significance lies in its ability to collect information from certain social networking sites.

The created Excel template is used to access and download the data. Excel is the engine that runs the graphing. NodeXL and similar tools have been developed to assist researchers of social networking put together relationships between users. Its graphing ability allows researchers to sift through large amounts of data from a social networking site and find associations that might have been missed. Investigators will find its easy use a significant advantage when dealing with social networking sites compatible with NodeXL.

Using NodeXL

Download the NodeXL template from http://nodexl.codeplex.com/. In the downloaded zip is an installer that adds the template to your Windows start menu. Once installed go to the Windows Start menu select, “All Programs,” then “ NodeXL” then click on “NodeXL Excel Template.” When the template is open select “Save As” another document name (that way you have the original template and if you mess something up playing with it you don’t have to reinstall). You will notice that on the Excel tabs there is an additional tab called “NodeXL.” Click in this tab and click on “Import.” For the few social networks it collects data from, it is quick and very powerful. Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube are the only current social networks programmed directly into the template. Selecting one of the import options for importing data offers various selections for the investigator (Figure 14.1).

Google+

Google+ was launched in June of 2011. In less than 2 years it has become the second largest social networking site with 500 million users. Google has integrated Google+ into other member services.

Investigating user data

Google+ has its own search engine which is similar to using Google general search engine. The investigator can simply enter a term and review the returned information. Of interest to the investigator is the fact that Google+ search site even alerts you to new postings after your initial search. The search page provides the investigator with postings, links to people and pages, and what is trending. There are also links to Google+ posts, photos, communities, and page. Google+ has the following shortcuts that can be useful to the investigator:

/=Select the search box at the top of the page

N=Move to the next comment on the current post

p=Move to the previous comment on the current port

A Wikipedia page against a St. Louis school was recently found by a Twitter follower in Virginia, who discussed the incident with other followers. They collectively came up with a plan which resulted in the threat being relayed to a local police department. However, the police complaint taker was less than cooperative according to reports and noting the department “did not have access to the Web.” Another neighboring agency was contacted and appropriate actions were taken to resolve the issue (Lasica, 2009). Obviously the initial police response to the Twitter complaint in a post-Columbine years was totally inappropriate, if not irresponsible.

Twitter “…is a service for friends, family, and co-workers to communicate and stay connected through the exchange of quick, frequent answers to one simple question: “What are you doing?” (NewsBlaze LLC, n.d.) For many new to the Twitterverse communicating in only 140 characters is a rather odd method of updating your friends or world. The investigator new to Twitter only has to go to a website like We Follow (http://wefollow.com/), to grasp the number of people that are now communicating in a short abbreviated form. Just look at the millions of followers that hang on a celebrity’s every Tweet. What exactly are the followers saying can be of huge interest to the investigator? Every Tweet and every follower of the tweets can provide the investigator with significant information. Not just what the tweet content is, but what data was it sent, what time and from what location. Who received the tweet and who forward the tweet (retweeted) to their followers? All of these can be of enormous use in the investigation when needed to verify times of events and establishing others awareness of the events in question.

Finding tweets

If you know the username go to www.twitter.com/{twittername}. The user’s page has all their “tweets.” The investigator can use the following other websites to search for and document tweets:

• Doesfollow (http://doesfollow.com): This site can find out if an individual twitter account is following another.

• Friend or Follow (http://friendorfollow.com): This site can search Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr. It provides the investigator with an easy look at the accounts, followers, friends, and fans. The free plan is limited. The pay for plans allows the downloading of the same data.

• Trendsmap (http://trendsmap.com/): This site gives the investigator the ability to track tweets from a geographical location.

Application program interface and social media content

An application program interface (API) is a set of commands used by programmers to interact with a program or operating system. It gives the programmer the direction to take when asking the program for information. Most social media sites allow applications to connect to their sites to develop an API to facilitate communication. Social networking sites use APIs as a service that can assist user’s access information. From an investigative point of view this provides a large hindrance to data acquisition without a tool adapted specifically for that API and that social networking site. The investigator can use this same information to access a variety of social networking sites and collect valuable information related to the investigation. A company called Apigee has a console that can be easily utilized to collect information through various social media APIs. The investigator can go to Apigee (https://apigee.com/console/) and access Twitter information through the API to get metadata that isn’t found on the Twitter user’s page. Figure 14.3 is an example of that data.

Other social networking sites of interest

There is a social networking type site for almost every kind of hobby or activity imaginable. Facebook and MySpace were not the first ones on the Internet. They happen to be some of the most used today, but many others exist. The investigator should not overlook these sites as they potentially could provide a valuable amount of detail in the investigation that might not be found elsewhere (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1

Other General Social Networking Sites of Interest

| Site | URL and Details |

| MySpace | http://www.myspace.com |

| Hi5 | http://hi5.com/ |

| Bebo | http://www.bebo.com |

| Formspring | http://www.formspring.me |

| http://www.pinterest.com |

A comprehensive list of the major active social networking sites is maintained on Wikipedia. This page has links to the major sites and has some background, the number of registered users.

Online social versus professional networking

People use social networking for a variety of reasons. Some may use them to get a date, expand their circle of friends, find people with similar hobbies or reconnect with old friends. The popularity has risen immensely over the past few years. However, professional eNetworking has a different purpose. Professional networking sites are used to connect people with contacts who can help them land a new or better job or lead to a business opportunity. These contacts include current and former colleagues, former bosses and coworkers, and even contacts not directly known to the user but from the same field. These professional sites offer similar functions to personal social networking sites such as “friends” referred to as contacts, email, public and private descriptions, pictures and groups with which to connect on various topics. Professional networking sites can have a significant amount of information about the person listed. Most of the information is listed on the “private” side of the user's account, but still there is a large amount of information that can be gleaned from the user’s public account. Each of the professional sites requires an account on the networking site to access the “private” data listed on the user’s account. Investigators need to be aware that some professional networking sites may inform the account holder who has been reviewing their profile. This is done to allow the user to connect with the viewer and start a dialogue between professionals. Another investigative aspect of these professional sites are user groups. These groups can inform the investigator about the types of interests a target has and can be useful in post arrest interviews and/or in locating additional victims.

Common business social networking sites

The most common business social networking sites include LinkedIn (http://www.linkedin.com), Plaxo (http://www.plaxo.com), and Spoke (http://www.spoke.com). Each of these sites offer similar services to their users. They intend to allow business networking between the users. Investigating each of these sites requires the investigator to obtain a user account. The investigator’s personal account should not be used for this purpose. An undercover account should be used for this purpose that cannot identify the investigator as the one viewing a user’s account.

Professional networking sites offer a large amount of user information to people using these sites and to add a significant amount of information about them to further develop their profile. Again, be aware that this is user-added content, which can be falsified. Professional networking sites generally have a public profile accessible by anyone and the private side containing additional information on the profile. Researching these sites is fairly simple. Most have a search function that allows you to identify the users by name. The benefit of these sites is that the users don’t use a nickname. The sites require a full name. The investigator can find the current position held by the user, their work history and their education. All of this can be of great value to the investigator when researching a target.

Finding individuals on social media sites

Looking for someone on a social networking site can sometimes be a challenge. Besides their name as a query term try searching using their email address to locate their profile. It sometimes is easier to locate a target’s friend or associate and check their profile for possible connection to your target’s profile. We previously have spoken about Spokeo and other sites that can assist in the search. There are other sites that can offer you additional options when searching for someone on a social networking site. These sites include:

General Social Networking Sites:

Social Mention, http://socialmention.com/

Addictomatic, http://addictomatic.com/

Who’s Talkin, http://www.whostalkin.com/

Kurrently, http://www.kurrently.com

Social Seek, http://socialseek.com/

Ice Rocket, http://www.icerocket.com/

Social Buzz, http://www.social-searcher.com/social-buzz/

Topsy, http://topsy.com/

Twitter-Specific Search Sites:

Back Tweets, http://backtweets.com/

Nearby Tweets, http://nearbytweets.com/

Tweet Alarm, http://www.tweetalarm.com/

Twazzup, http://www.twazzup.com

Social media evidence collection

This text has stressed online ESI needs to be collected, preserved, and reported in a manner that allows it to be used as evidence. Online ESI found on a social media site is even more susceptible to user alteration or destruction than that found on a website. Frequently, users have continuous live access to their social media profile. Few website administrators are continuously logged on to their site. Additionally, social media, either with or without special applications, is accessible by all manner of mobile devices. The nature of social media dictates this kind of constant user access and ability to interact, anywhere at anytime.

In Chapter 4, we outlined proper online ESI collection procedures (collection, preservation, and its presentation). These procedures are not just for high-tech crimes and computer forensics specialists. Just as every patrol officer knows how to bag and log physical evidence found during a vehicle or personal search, it is also possible to teach patrol officers and detectives how to collect a YouTube video or series of Facebook status updates. Indeed, the courts have generally accepted evidence collected from the Internet as long as its authenticity can be established. We have previously discussed in other chapters the tools available to document and collect the evidence found on the Internet. The investigator should consider the documentation of the evidence he finds at the time they find it. This is particularly the case as online ESI found on social media can be, and more likely will be, changed.

Social networking through photographs

Photo sites can be an often overlooked networking tool. Users will post photos of their travels, work, and leisure-time activities in large numbers. These photographs can provide a glimpse into the target’s life and provide the investigator with an understanding of the target’s personal behavior. These sites list the photos and any user-added caption about the photographs. Additionally, most of the photograph networking sites, unlike regular social networking sites, keep the Exif data in the image (we discussed extracting Exif data in Chapter 13). This can be a gold mine of information for the investigator depending on the camera settings used to take the photograph. The investigator can download the images and use a tool to extract the Exif data for examination. However, not all sites pass the Exif data through to the user’s pages. Facebook and others strip out the Exif data and reduce the image size for privacy and server space reasons. So the investigator may not have the Exif data available in that photo. Using the image search tools can assist the investigator in finding additional similar images that might in fact still retain the Exif data.

Flickr

Flickr (http://www.flickr.com/) is a photograph sharing social networking site. It has a feature that allows the geotagging of the images posted to the site. On the Flickr site a geotag is user-added information. This data can be public or private information. If it is public the investigator can easily identify the Exif data from the image. If it is private he may have to obtain the data by legal service or through some undercover connection to the user. Flickr has a search function that allows the investigator to search for names or usernames without logging into the service.

Photobucket

Photobucket (http://photobucket.com/) is another photograph sharing site similar to Flickr. It similarly allows for photo sharing as well as photo backup services, photo editing software, and printing services. Photobucket also has a search function that allows the investigator to search for names or usernames without logging into the service. Many other photo sharing sites exist and can be of use to the investigator. Some of those sites include:

• Deviant Art, http://www.deviantart.com/

• Shutterfly, http://www.shutterfly.com/

• Pbase, http://www.pbase.com/

• Photo.net, http://photo.net/

• Snapfish, http://www.snapfish.com/

• Smugmug, http://www.smugmug.com/

Social media investigations policy

We devoted much in this text to discussing policy and its need during Internet investigations. Social Networking investigations are no different. In Chapter 11, we discussed the need for policy on the use of social media during investigations. This emerging area has a great investigative capacity and requires that the investigators, their supervisors, and the agency/company management understand the requirements of using and documenting social networking data appropriately. The investigator should understand the agency/company policy regarding using social media during an investigation prior to commencing work on a case. A properly designed social media use policy for investigations should address how the agency/company communicates information on the investigation to the community it serves as well how the social media tools will be leveraged during the investigation. Obviously undercover social media has its own concerns as an investigative tool, which we noted in Chapters 10 and 11.

Training on investigating social networks

Policy is only a first step toward effective investigation of social networking sites. It must be backed up by training. There is a lot of focus in the commercial marketing world on how to use social networking as a marketing and sales tool. However training on the investigation and use of social networking as a community policing tool is something that is offered by very few organizations. Discussion within law enforcement really began relatively recently with the advent of conferences like the SMILE “Social Media In Law Enforcement” conference first held in April 7–9, 2010, in Washington DC. Even consultants are appearing in the market to assist officers and agencies deal with rebranding themselves in the social networking space like the people behind Cops 2.0 (cops2point0.com).

Regardless of your motives for moving into the social networking space, it like anything on the Internet needs to be understood to be employed correctly. Agencies must look at the policy they develop from both the community policing and the investigative perspective from a training point of view. Officers, new to social networking, need to be trained about what this part of the Internet is, its inherent risks and benefits, how an agency can benefit from being on social networking, and how to prevent exposing the agency or the officer to any liability. This training also needs to be provided to supervisors and managers, particularly as they are less likely than newer officers, to have used social networking sites.

Officers need to understand how the different social networks operate and where potential investigative information can be found. Officers also need to be aware of the agency’s policy on collection of investigative information versus intelligence collection and the different manner in which they each need to be treated. Training is available from a number of law enforcement specialists, which are reflected in Table 14.2.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided the reader with the understanding of how social networking has changed the investigative process. Social networking is a valuable tool for the investigator and needs to be considered in almost every investigation. Social networking evidence should not be a source of stress for the investigator. Proper understanding, provided through good policy and training will help the investigator find offenders, collect evidence, and bring a well-packaged case to their prosecutors or legal counsel for whatever the litigation may be. Social networking sites, both personal and professional, can provide the investigator with intelligence that can further their understanding of targets and victims. Online ESI found on social networking sites is even more susceptible to user alteration or destruction than that found on a website because users frequently have continuous access which is possible by the availability of today’s mobile devices. However, with proper policy, procedures, and training, online ESI can be collected and preserved in a manner that allows it to be used as evidence in any legal proceeding.

Further reading

1. Abrad-Santos, A. (2013, January 2). Inside the anonymous hacking file on the Steubenville “Rape Crew.” The Atlantic Wire. Retrieved from <http://www.theatlanticwire.com/national/2013/01/inside-anonymous-hacking-file-steubenville-rape-crew/60502/>.

2. Addictomatic: Inhale the Web. (n.d.). Retrieved from <http://addictomatic.com/>.

3. Advanced Internet Investigations. (n.d.). Retrieved from <http://www.advancedinternet.org/>.

4. Apigee. (n.d.). Apigee. Retrieved from <https://apigee.com/>.

5. Balolong, F. (2013, July 29). Top 10 social networking sites in the world [INFOGRAPHIC]. Social barrel: The latest social media news and marketing tips. Retrieved from <http://socialbarrel.com/top-10-social-networking-sites-in-the-world-infographic/52658/>.

6. Bartlett J, Miller C. How twitter is changing modern policing: The case of the Woolwich aftermath London: Demos; 2013; Retrieved from <http://www.demos.co.uk/files/_metpoliceuk.pdf?1371661838Bulletin,%20Issue%206,%20Winter%202011/2012/>.

7. Bayerl, P. (2012, September 29). Social media study in European police forces: First results on usage and acceptance. Comparative Police Studies in the EU (COMPOSITE). Retrieved from <www.composite-project.eu/tl_files/fM_k0005/download/SocialMedia-in-European-Police-Forces__PreliminaryReport.092012.pdf/>.

8. Bebo. (n.d.). Bebo. Retrieved from <http://www.bebo.com/>.

9. Becker, J. (n.d.). How to stay out of Facebook jail—Need to know tips for online marketers. Julie Becker’s Guide to Residual Income. Retrieved from <http://igetpaidonline.biz/facebook-jail/>.

10. Boyd D, Ellison N. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2008;13(1):210–230.

11. Brenner, J., & Smith, A. (2013 August 5). 72% of Online adults are social networking site users. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from <http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/social-networking-sites.aspx/>.

12. Brick, M. (2010 February 18). Man crashes plane into Texas I.R.S. office. The New York Times. Retrieved from <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/19/us/19crash.html?_r=1&/>.

13. Caeleigh Cope v. Steven D. Prince, et al., Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas, CV-12-781824.

14. Cops 2.0. (n.d.). Retrieved from <http://cops2point0.com/>.

15. CybercrimeSurvival.com—Learn the investigative tools you need to succeed. (n.d.). CybercrimeSurvival.com. Retrieved from <http://www.cybercrimesurvival.com/>.

16. Denef S, Bayerl P, Kaptein N. Cross-European approaches to social media as a tool for police communication Hampshire, UK: CEPOL European Police Science and Research Bulletin; 2012.

17. deviantART: Where ART meets application! (n.d.). deviantART. Retrieved from <http://www.deviantart.com/>.

18. Dissell, R. (2012, September 2). Rape charges against high school players divide football town of Steubenville, Ohio. Cleveland OH Local News, Breaking News, Sports & Weather—Cleveland.com. Retrieved from <http://www.cleveland.com/metro/index.ssf/2012/09/rape_charges_divide_football_t.html/>.

19. DoesFollow—Find out who follows whom on Twitter. (n.d.). DoesFollow. Retrieved from <http://doesfollow.com/>.

20. Edward de Bono. (n.d.). BrainyQuote.com. Retrieved from <http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/e/edwarddebo124441.html/>.

21. Facebook. (n.d.). Facebook. Retrieved from <facebook.com/>.

22. Facebook Form 10-Q. (2012, July 31). Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved from <http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1326801/000119312512325997/d371464d10q.htm#tx371464_14/>.

23. Facebook Jail. (n.d.). Facebook. Retrieved from <https://www.facebook.com/groups/439720179385480/>.

24. Gonzalez, A. (2010, February 19). Social media forever changing the way we cover news. YNN—Your News Now. NEWS—Austin/Round Rock/San Marcos. Retrieved from <http://austin.ynn.com/content/news/267483/social-media-forever-changing-the-way-we-cover-news/>.

25. Google Images. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <http://www.google.com/imghp/>.

26. Google Takeout. (n.d.). Google. Retrieved from <www.google.com/takeout>.

27. Hetherington Group—Training. (n.d.). Hetherington Group—Welcome. Retrieved from <http://hetheringtongroup.com/training.shtml/>.

28. hi5 (n.d.). hi5. Retrieved from <http://hi5.com/>.

29. Hofmann, M. (2010, March 16). Social networking monitoring. Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved from <www.eff.org/deeplinks/2010/03/eff-posts-documents-detailing-law-enforcement/>.

30. Home CEPOL—European Police College. (n.d.). CEPOL—European Police College. Retrieved from <https://www.cepol.europa.eu/>.

31. ICAC Training and Technical Assistance. (n.d.). Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force. Retrieved from <http://www.icactraining.org/>.

32. ilektrojohn creepy @ GitHub. (n.d.). ilektrojohn creepy @ GitHub. Retrieved from <ilektrojohn.github.com/creepy/>.

33. Internet Investigations Training Program (IITP) at Federal Law Enforcement Training Center. (n.d.). FLETC: Federal Law Enforcement Training Center. Retrieved from <http://www.fletc.gov/training/programs/investigative-operations-division/economic-financial/internet-investigations-training-program-iitp/>.

34. Jefferson County QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau. (n.d.). State and County QuickFacts. Retrieved from <http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/39/39081.html/>.

35. Koenninger, K. (2012, May 4). Outraged dad says law firm and insurer snooped on injured girl’s Facebook page. Courthouse News Service. Retrieved from <http://www.courthousenews.com/2012/05/04/46239.htm/>.

36. Kurrently Inc. (n.d.). Kurrently Inc. Retrieved from <www.kurrently.com/>.

37. Lasica, J. (2009, March 4). Social media and a school death threat. Socialmedia.biz. Social Media News and Business Strategies Blog. Retrieved from <http://socialmedia.biz/2009/03/04/social-media-and-a-school-death-threat/>.

38. Lorraine v. Markel AM. Ins. Com, 241 F.R.D. 534, 538 (D.Md. 2007).

39. Loco Citato. (n.d.). Loco Citato. Retrieved from <http://www.lococitato.com/>.

40. Macur, J., & Schweber, N. (2012, December 16). Rape case unfolds online and divides Steubenville. The New York Times—Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. Retrieved from <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/17/sports/high-school-football-rape-case-unfolds-online-and-divides-steubenville-ohio.html?pagewanted=all/>.

41. McCullagh, D. (2010, March 16). Feds consider going undercover on social networks.| Politics and Law—CNET News. Technology News. Retrieved from <http://news.cnet.com/8301-13578_3-20000550-38.html/>.

42. Meltwater IceRocket. (n.d.). Meltwater IceRocket. Retrieved from <http://www.icerocket.com/>.

43. Myspace. (n.d.). Myspace. Retrieved from <www.myspace.com/>.

44. MySpace Tracker—MixMap. (n.d.). MixMap—MySpace Tracker. Retrieved from <http://www.mixmap.com/>.

45. Nearby tweets: Search local tweets by location and keyword. (n.d.). Nearby Tweets. Retrieved from <http://nearbytweets.com/>.

46. NodeXL: Network Overview, Discovery and Exploration for Excel—Home. (n.d.). NodeXL. Retrieved from <http://nodexl.codeplex.com/>.

47. NW3C Home. (n.d.). National White Collar Crime Center. Retrieved from <http://www.nw3c.org/>.

48. Owyang, J. (2011, July 29, ). Number of corporate social media accounts on rise: Risk of a social media help desk. Social Media, Web Marketing. Web Strategy By Jeremiah Owyang. Retrieved from <http://www.web-strategist.com/blog/2011/07/29/number-of-corporate-social-media-accounts-hard-to-manage-risk-of-social-media-help-desk/>.

49. Parrack, D. (2010, March 17). FBI tracks criminals via social networking sites. Tech.Blorge.com. Retrieved from <tech.blorge.com/Structure:%20/2010/03/17/fbi-tracks-criminals-via-social-networking-sites/>.

50. PBase.com. (n.d.). PBase.com. Retrieved from <http://www.pbase.com/>.

51. Pearson, M., Carter, C., & Brady, B. (2013, March 19). More social media trouble in Steubenville. CNN.com—Breaking News, U.S., World, Weather, Entertainment & Video News. Retrieved from <http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/19/justice/ohio-steubenville-case/>.

52. Photo Books, Holiday Cards, Photo Cards, Birth Announcements, Photo Printing: Shutterfly. (n.d.). Shutterfly. Retrieved from <http://www.shutterfly.com/>.

53. Photo Sharing. Stunning Photo Websites. SmugMug. (n.d.). SmugMug. Retrieved from <http://www.smugmug.com/>.

54. Photography community, including forums, reviews, and galleries from Photo.net. (n.d.) Photo.net. Retrieved from <http://photo.net/>.

55. Pinterest. (n.d.). Pinterest. Retrieved from <www.pinterest.com/>.

56. Plaxo—Your address book for life. (n.d.). Plaxo. Retrieved from <http://www.plaxo.com/>.

57. Presutti, C. (2013, April 26). Multi, social media play huge role in solving Boston bombing. VOA—Voice of America English News—VOA News. Retrieved from <http://www.voanews.com/content/multi-social-media-play-huge-role-in-solving-boston-bombing/1649774.html/>.

58. Real Time Search—Social Mention. (n.d.). Real time search—Social mention. Retrieved from <http://socialmention.com/>.

59. Real-time local Twitter trends—Trendsmap. (n.d.). Trendsmap. Retrieved from <http://trendsmap.com/>.

60. SEARCH High-Tech Crime—ISP List. (n.d.). SEARCH: The online resource for justice and public safety decision makers. Retrieved from <http://search.org/programs/hightech/isp/>.

61. SEARCH: The Online Resource for Justice and Public Safety Decision Makers. (n.d.). SEARCH. Retrieved from <http://www.search.org/>.

62. Smith, C. (2013, July 21). By the numbers: 20 amazing witter stats. Digital Marketing Ramblings. The Latest Digital Marketing Tips, Trends and Technology. Retrieved from <http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/march-2013-by-the-numbers-a-few-amazing-twitter-stats/>.

63. Smith, C. (2013, July 24). (August 2013 update) By the numbers: 39 amazing Facebook stats. Digital Marketing Ramblings. The Latest Digital Marketing Tips, Trends and Technology. Retrieved from <http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/by-the-numbers-17-amazing-facebook-stats/>.

64. Snapfish. Photo Prints, Photo Books, Photo Cards, Personalized Photo Gifts Occasion. (n.d.). Snapfish. Retrieved from <http://www.snapfish.com/>.

65. Social Buzz—Real Time Search for Facebook, Twitter and Google+. (n.d.). Social Buzz. Retrieved from <http://www.social-searcher.com/social-buzz/>.

66. Social Media Search ToolWhosTalkin? (n.d.). Retrieved from <http://www.whostalkin.com/>.

67. Social Networking Monitoring. (n.d.). Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved from <https://www.eff.org/foia/social-network-monitoring/>.

68. Socialseek. (n.d.). Socialseek. Retrieved from <http://socialseek.com/>.

69. Spoke: Discover Relevant Business Information. (n.d.). Spoke. Retrieved from <http://www.spoke.com/>.

70. Spokeo People Search: White Pages, Find People (n.d.). Spokeo. Retrieved from <http://Spokeo.com/>.

71. Spring.Me.(n.d.). Spring.Me. Retrieved from <http://www.formspring.me/>.

72. Steubenville Under Siege—News, Sports, Jobs—The Intelligencer / Wheeling News-Register. (n.d.). The Intelligencer / Wheeling News-Register. Retrieved from <http://www.theintelligencer.net/page/content.detail/id/584526/Steubenville-Under-Siege.html?nav=511/>.

73. Steubenville, OH Population and Races. (n.d.). USA.com: Location information of the United States. Retrieved from <http://www.usa.com/steubenville-oh-population-and-races.htm/>.

74. Steubenville, OH—Forbes. (n.d.). Information for the World’s Business Leaders—Forbes.com. Retrieved from <http://www.forbes.com/places/oh/steubenville/>.

75. Sullivan, B. (2011 April 15). Just how creepy is “Creepy”? A Test-drive. NBC News.com. Breaking News & Top Stories. Retrieved from <http://www.nbcnews.com/technology/just-how-creepy-creepy-test-drive-6C10406861/>.

76. TinEye Reverse Image Search. (n.d.). TinEye Reverse Image Search. Retrieved from <http://TinEye.com/>.

77. Topsy. (n.d.). Topsy. Retrieved from <http://topsy.com/>.

78. Twazzup—Twitter Real-time Monitoring and Analytics. (n.d.). Twazzup. Retrieved from <http://www.twazzup.com/>.

79. Tweetalarm.com. (n.d.). Tweetalarm.com. Retrieved from <http://www.tweetalarm.com/>.

80. Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved from <twitter.com/>.

81. Twitter Search: BackTweets. (n.d.). BackTweets. Retrieved from <http://backtweets.com/>.

82. Twitter WebCase WebLog. (2011, April 5). Vere software—Online evidence collection & documentation. Retrieved from <http://veresoftware.com/blog/?tag=twitter/>.

83. Watkins, T., & Presse, A. (2013, May 1). Google Plus is outpacing Twitter. Business Insider. Business Insider. Retrieved from <http://www.businessinsider.com/google-plus-is-outpacing-twitter-2013-5#ixzz2bh913KCy/>.

84. Wefollow: Discover prominent people. (n.d.). Wefollow. Retrieved from <http://wefollow.com/>.

85. Welcome to Flickr—Photo Sharing. (n.d.). Flickr. Retrieved from <http://www.flickr.com/>.

86. What is Twitter? (n.d.). NewsBlaze LLC. Retrieved from <http://tweeternet.com/>.

87. Who Unfollowed Me? | Friend or Follow. (n.d.). Who unfollowed me? Retrieved from <http://friendorfollow.com/>.

88. World’s Largest Professional Network. LinkedIn. Retrieved from <http://www.linkedin.com/>.

89. yoName—People Search. Search for People Across Social Networks, Blogs and More. (n.d.). yoName. Retrieved from <http://yoname.com/>.