Chapter 6

Sleep Problems

Abstract

“Our baby won’t sleep and we’ve been up all night for the past 6 months. Nothing works! We’ve tried ignoring the crying, rocking him back to sleep, and riding in the car for hours on end. We’re exhausted, at our wit’s end, and nobody is functioning in the house. We can’t go on another day like this. Please help us!” These could be the words of many families who have struggled with a sleepless baby. For many parents, solving the child’s sleep problems is extremely challenging, and therefore it is important to understand the complexities that underlie falling and staying asleep.

Keywords

sleep–wake cycles

ADHD

sleep problems

self-soothing

hypersensitive child

“Our baby won’t sleep and we’ve been up all night for the past 6 months. Nothing works! We’ve tried ignoring the crying, rocking him back to sleep, and riding in the car for hours on end. We’re exhausted, at our wit’s end, and nobody is functioning in the house. We can’t go on another day like this. Please help us!” These could be the words of many families who have struggled with a sleepless baby. For many parents, solving the child’s sleep problems is extremely challenging, and therefore it is important to understand the complexities that underlie falling and staying asleep.

Sleep plays an important role in restoring the body, allowing it to absorb nutrients into tissues and to stimulate brain protein synthesis (Adams, 1980). When a person experiences sleep problems, everyday functioning and learning is compromised. A person who is not sleeping is often inattentive, has trouble remembering things and thinking clearly, is often irritable, and, if sensory defensiveness is present, the person may be more bothered by touch, noise, and sensory stimulation.

The task of falling and staying asleep relates to several developmental tasks depending upon the age of the child. For the infant, these tasks include:

• regulating basic sleep–wake cycles and arousal states,

• internalizing daily routines and schedules,

• transitioning from active and quiet alert states to sleep,

• screening out noise from the environment when falling asleep,

• self-calming when distressed or when awakened in the night, and

• feeling attached to the caregiver while feeling secure in separating from them to sleep.

Caregivers help to support regulation of sleep–wake cycles by establishing set times for naps and bedtime, by enacting bedtime rituals (e.g., bath, story) and by helping the child to use soothing devices in the crib to help in falling asleep and for use when reawakening occurs. The caregivers must provide structure to avoid overstimulation, which may include noise stimulation, such as the television. They also provide experiences that support both attachment and separateness. Some of the tasks confronted by toddlers and older children include:

• calming down after a stimulating day of activities,

• receiving a balanced sensory diet of movement stimulation and calming activities,

• screening out noise from the environment when falling asleep,

• negotiating fears of dark places and of being alone,

• tolerating limits set by caregivers around bedtime rituals,

• feeling attached to the caregiver while feeling secure to separate for sleep, and

• developing autonomy.

It is important for caregivers to help the toddler negotiate different levels of sensory stimulation through the day without becoming overstimulated. The child needs to internalize and follow routines that caregivers have established while becoming comfortable with tolerating rules as they learn to assert their autonomy.

Over the course of the person’s life, sleep often takes on special meanings. For some children, falling and staying asleep may become problematic, as they age even when it wasn’t an issue before. It is not uncommon for sleep to become a problem if the child faces a high level of stress in their home and school life or if they worry about things happening in their life.

1. Sleep problems in children

Sleep problems often occur in children with regulatory disorders (DeGangi & Breinbauer, 1997). In our research, we found, that sleep problems were prevalent in this group of children through 18 months, seeming to peak at 10–12 months when separation anxiety first emerges. By 19–24 months, many children with regulatory disorders resolved in falling asleep but continued to awaken frequently in the night. Our data suggest that the sleep problem will differ depending upon the age of the child, thus supporting the notion that sleep problems are related to biological and social regulation, and the ability to form a secure attachment to the caregiver (Anders, 1997).

Certain symptoms seem to occur at different ages when sleep problems are present. At 7–9 months, sleep problems are often associated with a high need for vestibular stimulation. Caregivers often report that the only way to help their baby fall asleep is to bounce or rock their baby for long periods of time. Some parents place their infant in an infant swing or drive them in the car for an hour or so, allowing the movement to help the infant fall asleep. At 10–12 months, separation anxiety seem to compound the sleep disturbance. Caregivers often report that their infant is clingy and can only fall asleep in their arms. Distress upon awakening in the night may be accompanied by anxiety that the child is alone in their crib rather than in the parent’s arms. By 13–18 months, many children with sleep problems show a high need for movement stimulation. Often parents report how their child’s excessive need for movement seems to increase their arousal, making it more difficult for the child to fall asleep at night. Distress at sounds in the environment is often present at 13–18 months. Many parents state that their child can only sleep if the parents help to screen environmental sounds by using white noise (i.e., oscillating fans, white noise audiotapes). Severe separation anxiety may also be a contributing factor at this age. By 19–24 months, falling asleep is often less an issue; however, waking in the night usually remains. Many of these children continue to crave movement and appear restless throughout the night.

Sleep problems have been attributed to a number of other factors. In one study, childhood sleep problems seemed related to maternal distress and depression during pregnancy (Armstrong, O’Donnell, McCallum, & Dadds, 1998). Sleep interruption was found to occur more frequency in infants with gastro-esophageal reflux (Ghaem et al., 1998). Sleep disorders can also result from pulmonary problems, neurological problems, family issues, and psychological problems in the child (Rosen, 1997). In addition, children with difficult temperament and greater emotional reactivity were found to be more likely to have sleep disturbances (Owens-Stively et al., 1997). The authors also found that parental laxness and inconsistencies in adhering to sleep routines contributed to sleep problems in children.

2. Impact of sleep problems on development

Many young infants experience sleep problems, which resolve by 9 months of age, however, when the sleep problems persist, there may be constitutional and/or emotional problems that underlie the sleep disturbance. In our research, we found that many infants with regulatory disorders resolve in their sleep problem as they mature (DeGangi, Breinbauer, Roosevelt, Greenspan, & Porges, 2000). However, children who have moderate regulatory disorders during infancy (e.g., 3 or more problems, such as sleep, irritability, and sensory defensiveness) who did not sleep, 22% were likely to develop behavioral and emotional problems at age 3 years. We also found that 46% of the children in our sample who were diagnosed as having pervasive developmental disorders at 3 years had sleep problems during infancy.

In other studies, the link between sleep problems and behavioral disorders have been implicated. For example, problems falling and staying asleep were documented in about 28.7% of 3 year olds who had behavioral problems (Richman, Stevenson, & Graham, 1982). These problems tended to persist in 2/3 of the sample with behavioral problems lasting through 8 years of age. Others have also reported that children with developmental disorders, such as mental retardation and autism have frequent night awakenings and sleep phase shifts (Okawa & Sasaki, 1987). It seems that children who experience sleep problems have anxiety or other emotional problems, such as an inability to separate from the caregiver or to tolerate being alone. Poor sleepers (e.g., inability to soothe themselves back to sleep without disturbing others) tend to have more behavioral problems, a more difficult temperament, and more adverse early medical histories (Minde et al., 1993). Sleep problems also seem to affect the child’s capacity to focus attention and may cause the child to look as though they have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Dahl, 1996). In another study, it was found 25% of children with ADHD suffer from habitual snoring (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea), which could be contributing to their symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity (Chervin, Dillon, Bassetti, Ganoczy, & Pituch, 1997).

3. Development of sleep–wake cycles

Understanding normal sleep–wake states in the child is useful so that professionals can guide families in addressing the child’s sleep problems. Changes occur not only in duration of sleep but also in the quality of sleep [e.g., rapid eye movement (REM)/nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep] and the number of times that a child awakens in the night. The newborn’s sleep cycle is occupied by 50% REM sleep in contrast to 20% REM sleep in the adult. As the child matures, there is a functional decrease in REM sleep. The newborn does not experience Stage 4 NREM sleep and their sleep rhythms have a 50-minute cycle in contrast to the adult’s 90 minute sleep cycle (Anders, 1997). The presence of REM sleep helps in the person’s emotional well-being because that is when the brain’s unconscious reworks conscious thinking and integrates it for emotional adaptation (Moruzzi, 1966). In Table 6.1, guidelines are provided related to duration of sleep (Ferber, 1985), percent of infants who sleep through the night (Moore & Ucko, 1957), and amount of active sleep that occurs in the night (Anders, Keener, Bowe, & Shioff, 1983).

Table 6.1

Normal trends in sleep patterns

| Age of child | Sleep patterns in the typically developing child |

| Newborn | Sleep 16.5 hours/day. |

| 2–3 months | Sleep 3–4 hours continuously, then awaken for feeding. |

| Active sleep decreases to 43%. | |

| 71% of children sleep through the night at 3 months. | |

| 4 months | Sleep for longer periods at night with shorter naps during the day. |

| 6 months | Sleep 14.25 hours/day. |

| Awaken 1–2 times in a 5–6-hour sleep cycle. | |

| 1/3 to 1/2 of infants fall asleep after awakening on their own. | |

| 84% of children sleep through the night. | |

| 10 months | 90% of children sleep through the night. |

| 12 months | Sleep 13.75 hours/day. |

| Active sleep decreases to 30%. | |

| 2 years | Sleep 13 hours/day. |

| Preschoolers | Sleep 11–13 hours/day. |

| School-aged children | Sleep 10–11 hours/day. |

| About 69% have intermittent sleep problems. | |

| Preteen and teenagers | 40% less slow-wave sleep, but need at least 10–11 hours sleep/day. Many teens receive less sleep and go to bed later, which results in daytime sleepiness. |

4. Stages of sleep

Sleep consists of NREM and REM sleep and together these comprise five stages of sleep.

Stage 1 (NREM): First stage, sleep is when the person falls asleep and engages in light sleep. They are still alert to sensory stimulation in the environment (e.g., light turning on, sound of TV) and brain activity is mixed. Alpha brain waves (about 8–12 cycles per second) are reduced to about 50% of the brain’s activity. Theta waves (about 4–7 cycles per second) increase during which time the person is aware of turning off consciousness and entering sleep. During this stage, the eyes move slowly back and forth. The muscles of the body relax but in some people, muscle contractions cause them to jolt into wakefulness. This can assimilate the feeling of falling. Some people stay in this stage of sleep for less than 10 minutes. Others with sleep problems can take 30 minutes to 2 hours before they fall into the next stage of sleep.

Stage 2 (NREM): This stage is moderately light sleep and consists of slowing of heart rate and dropping of body temperature. Slower brain waves are intermittently mixed with faster waves, which are called sleep spindles and K-complexes. About half of the person’s sleep time is in this stage.

Stage 3 (NREM): Slow-wave sleep transitions to delta sleep waves in this stage. These consist of high-voltage, slow wave activity (1–3 cycles per second).

Stage 4 (NREM): This is the deepest sleep state when it’s very difficult to arouse the person from sleep. Persons who have been sleep-deprived often go quickly to Stages 3 and 4 to restore their body. Sleep terrors and sleepwalking often occur during this stage.

REM Sleep: During REM sleep, the eyes move in bursts of back-and-forth movements. Dreaming occurs during this stage, which can occupy about 20–25% of the person’s overall sleep. The brain waves are low voltage, fast frequency waves that assimilate the brain’s activity as if the person were awake, however, the body succumbs to a generalized inhibition from the lower brain stem centers. Muscles are temporarily paralyzed yet heart rate, respiration, and metabolism increase. Sexual arousal may occur and the body becomes more sensitive to temperature in the environment. Memory consolidation and learning are critical functions of REM sleep. During REM sleep, the person can be awakened fairly easily.

Overall sleep cycle: In the typical child, the sleep cycle is not a predictable pattern. As the person first falls asleep, the pattern may go as follows:

Stage 1 for 10 minutes; Stage 2 for 10–25 minutes; Stage 3 for 5 minutes; Stage 4 for 20–40 minutes, return to Stage 3 for 1–2 minutes; Stage 2 for 5–10 minutes, then REM sleep for 5 minutes (Carskadon & Dement, 2005). REM sleep tends to begin about 90 minutes into a person’s sleep and may cycle about every 90 minutes. In the beginning of a person’s sleep, Stages 3 and 4 tend to be longer and gradually REM sleep lengthens as the night progresses.

Circadian rhythms: In addition to the sleep rhythm cycle, the body times its sleep around a 24-hour day. Our bodies are sensitive to daylight, a function of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, a part of the hypothalamus. The suprachiasmatic nucleus triggers the release of melatonin from the pineal gland. This brain structure plays an important role in regulating the circadian rhythm, helping us to sleep at night and be awake during the daytime. The circadian rhythms can be easily disrupted if we travel to another time zone, are forced to awaken during the night for an emergency, or if one works the night shift (Kelly, 1991a).

5. Self-soothing and the process of sleep

When sleep problems exist, there may be constitutional, health, and/or emotional problems that underlie the sleep disturbance. Many children with disorders of dysregulation experience a combination of sleep, irritability, depression, anxiety, and sensory defensiveness. Sleep problems can affect the person’s capacity to focus attention and to demonstrate mental clarity in thinking. In some individuals, poor sleep may cause them to appear to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Dahl, 1996). In addition, when a person sleeps poorly, they are apt to have poor motor coordination and are more apt to have accidents due to impaired reaction times and poor mental focus. Hypersensitivities to touch, noise, and overall stimulation levels can worsen, thus causing the person to feel more defensive than they already are to sensory stimulation. If the person’s sleep problem becomes protracted over time, they may experience hallucinations, psychotic thinking, poor judgment, and sometimes, suicidal thinking.

In terms of sleep patterns, there seem to be two types of infants—those who signal their parents, calling for help when they awaken, and those who can self-soothe and return to sleep on their own (Anders, 1979). The infants who signal their parents by waking and crying were typically put in their crib already asleep and did not have a “sleep aide” (e.g., a pacifier, stuffed doll). Self-soothers were usually put in their bed awake and had a sleep aide so that when they awakened, they used their sleep aide to help them fall back to sleep instead of relying on their parents to do this for them. Minde et al. (1993) found that the number of times that a poor and good sleeper reawaken do not differ, however, the parents of poor sleepers feel that their child awakens more because the infant is relying on the parent to put them back to sleep. Using time-lapse videotaping for children between 12 and 36 months, poor sleepers were reported to awaken 2.7 times per night by their parents, but in actuality, they awakened 3.6 times per night. In contrast, parents of good sleepers reported that their child awakened 0.5 times per night when they actually awakened 3.2 times per night. In our modern society, parents are highly attuned to their child’s awakenings because of the use of sound monitors in the child’s room. Parents often find that they need to learn to resist going into their child’s bedroom upon the slightest rustling, whimper, or sound.

6. The sleep environment, cultural beliefs about sleep, and family sleep patterns

An important aspect of sleep is where the child sleeps and what the child’s sleep environment is like. Sleeping alone in a bed or sleeping in the family bed are very different experiences. One must keep in mind how old the child is and their developmental needs at the time if the child is sleeping with the parents. For example, it is very common for parents to have their young infant sleeping in a bassinet in their bedroom until the baby reaches 3 or 4 months of age. Unless the parents support the family bed philosophy, a child may seek to sleep with their parents or the parents may use this as a solution when frequent nighttime awakenings occur that disrupt the family’s sleep. Children often enjoy the closeness of sleeping with their parents and quickly become used to a family sleeping arrangement.

The parents’ cultural views, personal beliefs, and the child’s and parents’ ability to separate from one another often affect when the child learns to sleep alone. Some parents hold the belief that the child will regulate on their own and will signal them when they are ready to sleep alone in their own bed. Likewise, some parents feel that their child cannot fall asleep on their own and feel they must breast- or bottle-feed them or rock and hold them until the child falls asleep. In some cultures, group-sleeping arrangements are used to reinforce bonding which serve a protective function in the family. This philosophy may work well for some families in American society, but it may not work well for others depending upon the child’s constitutional, developmental, and emotional issues and the demands placed upon the family to function during the daytime (e.g., to separate from one another to go to day care, school, or work). Because of the demands placed on children in our society, once a child reaches 7 months and is beginning to negotiate issues related to trust, separation, and attachment, it is useful for the child to sleep in their own space except in special circumstances. The issue of sleeping alone becomes particularly important as the child nears the second year of life. It provides the child an opportunity to feel secure with one’s own separateness, thus paving the way for good self-esteem and self-reliance.

Some children have difficulty settling for sleep because of problems, such as hyperactivity or sensory defensiveness that make it hard for the child to self-calm, to become physically comfortable in the bed, or to screen noises from the environment. When this occurs the child may need certain props in the bedroom to help them sleep. This will be discussed in detail in the treatment section of this chapter.

A home environment that is noisy and stimulating with few established routines will be less conducive to sleep than one that provides balanced levels of stimulation and calming, regularity in routines, an organized bedtime ritual, and a sleep environment that helps the child feel secure and calm. If the bedroom is very stimulating with busy patterns and high intensity colors on the wall and with disorganization in the room (e.g., toys strewn around the floor), the child will be less able to decrease their arousal level for sleep. Likewise, the child will be affected by a home environment that is busy or very noisy. For example, there may be other children sharing the bedroom and making noise, the TV may be on after the child has tried to go to sleep, or adults in the house have different sleep schedules because of their work life.

Where the parents choose to have the child sleep is often a very important piece of information that helps to understand the attachment process. Oftentimes this information is best obtained when doing a home visit. Sometimes parents may be reluctant to create separate space for a child because of their own need to have the child remain in their bedroom. This was demonstrated with 18-month old Emily who was sleeping with her parents but was giving signals that she would like her own space and separateness, playing games when she would leave her parents’ side to go find things elsewhere in the room. When we did the home visit, we asked if Mrs. C. could show us Emily’s bedroom. It turned out that Emily did not have a bedroom of her own despite the fact that the family had a three-bedroom home with only one child. One bedroom was the room where the parents slept with Emily, the other two bedrooms had been converted to a home office and a room for Mrs. C.’s weaving loom, yarns, and quilt projects. We talked about the importance of Emily having her own place and suggested that perhaps mother’s project room might become Emily’s bedroom. Mrs. C. then complained, saying “Where will I do my projects?”

In another situation which we found particularly disturbing, we learned that Maya, an adopted 9 month old baby, slept downstairs out of ear shot of the parents’ bedroom in the basement because her parents could not tolerate her screaming through the night. Mr. and Mrs. T. were ambivalent about adopting Maya, particularly when they discovered that she had a hearing impairment. They were pondering whether to send her back to her country of origin. As we worked with the family on attachment and understanding Maya’s developmental needs, her screaming at night lessened. We felt that we had achieved a major breakthrough in their relationship with Maya when they created a bedroom for her next to their own bedroom, showed genuine signs of affection for Maya, and became interested in learning how to use simple signs to communicate with her.

When children sleep with their parents, the preschool or school-aged child may become aroused by the physical contact but not know how to handle these impulses. Some children become aggressive toward their parents, siblings, or peers during the daytime as a way of trying to discharge these impulses. The child may have difficulty accepting limits, complying with requests, and tolerating distress because of the lack of boundaries at nighttime. In addition, the child may witness sexual activity between the parents that they do not know how to handle emotionally. Usually the child misconstrues the sexual activity as aggressive. Addressing the sleep problem becomes more than simply one of working on separation and individuation, but one that is tied up in physical and emotional boundaries.

7. Sleep problems in children with dysregulation

There are several different types of sleep problems, some more common at different ages. The most common sleep problem is insomnia when the child has trouble falling and staying asleep. Occasionally one sees children with excessive somnolence, who sleep many hours of the day and night. As children develop, they may develop unusual sleep behaviors, such as recurring night terrors or nightmares. The child may have an unusual sleep cycle, sleeping for a few hours at a time, then fully awakening. Of course, whenever sleep problems are present, it is important to rule out medical problems including sleep apnea, painful conditions, such as reflux or severe ear infections or allergies (e.g., milk intolerance) that may contribute to the sleep problem.

Sleep problems occur in about 15% of children and are even more common among children with dysregulation, especially those with anxiety, depression, attention deficit disorder, and mood disorder. Insomnia is the most common of sleep disorders and constitutes an inability to get good quality sleep for optimal functioning during the waking hours. Many persons with insomnia suffer from restless leg syndrome or stereotypic leg twitches. It is also quite common for such individuals to have sensory hypersensitivities, especially to sound, light, and touch which agitate them as they try to fall and stay asleep. Sleep studies on insomniacs show that they have shorter sleep duration, more frequent awakenings in the night and poor quality sleep. The typical insomniac experiences a great deal of anxiety about falling asleep. In addition, studies have shown that 70% of insomniacs have an emotional problem, especially depression and in many cases of such individuals, they often end up being treated with medications for sleep problems rather than the underlying depressive disorder. The depressed patient is apt to show less delta sleep (Stages 3 and 4 slow-wave) and enter REM sleep shortly after they fall asleep (Kelly, 1991b).

Other sleep disturbances include the parasomnias, which are associated with sleep state or sleep stages. Sleepwalking is one type occurring during Stage 3 or 4 slow-wave sleep. The child will get out of bed, walk about clumsily with their eyes open. They may do things like go to the bathroom, speak incoherently to others, or even eat a meal without remembering it in the morning. Night terrors and nightmares can occur during REM or slow-wave sleep. Often a child experiencing a night terror has it early in the sleep cycle. They may scream or stare wide-eyed in terror at something they perceive. Attempts to console them have no effect and may actually be integrated into the experience of terror. Often the child has no memory of the attack in the morning. In children, the anxiety they experience is intense with physiological responses including sweating, dilated pupils, and problems breathing. In contrast, persons who have terrifying dreams during REM sleep in the early morning hours tend to remember them. These dreams have a more coherent story line similar to other REM sleep dreams.

Periodic breathing pauses, also known as sleep apnea is a common sleep disturbance. It is thought that the problem is generated from suppression of activity in the medulla’s respiratory center. As a result, the diaphragm and intercostals muscles stop working for about 15–30 seconds. The throat muscles collapse and there are extreme changes in the concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood. This phenomenon usually arouses the sleeper to gasp which assists in refilling the lungs. Some persons with sleep apnea have attacks up to 500 times per night. The most common type of sleep apnea is when there is an obstruction in the upper airway causing a lack of air flow, however, some individuals have apnea that is caused by central nervous system dysfunction that causes them to stop breathing. It feels like they are suffocating in their sleep, a problem that occurs with sudden infant death syndrome. Usually, the person with sleep apnea is initially diagnosed by their caregiver who notices their chronic snoring. In adults, continuous positive airway pressure is the treatment of choice. It consists of a mask that fits over the nose and delivers high-pressure air to keep the throat open for breathing.

Narcolepsy is another type of sleep disturbance whereby the person has an irresistible urge to sleep, which is less common in children. Their drowsiness is overwhelming and can occur suddenly during tasks like driving a car, which can cause the person to have a car accident. The person with narcolepsy often experiences a loss of muscle tone during their sleep episodes. Their knees might buckle, their jaw sags and the head and trunk slump forward. Often the narcoleptic will drift immediately into REM sleep from a waking state. They fall asleep rapidly, usually within 2 minutes in comparison to the typical 15 minutes of a normal person. It is thought that narcolepsy is caused by activation of the brain stem neurons that send inhibitory signals to the spinal motor neurons during REM sleep (Kelly, 1991b).

In this next section, the problems of insomnia or excessive somnolence will be described in detail as they relate to different regulatory and sensory profiles. These two types of sleep problems are emphasized because they are more likely to occur in children with regulatory disorders.

7.1. The hypersensitive child

Children with sensory integrative dysfunction related to hypersensitivities to touch and sound might experience sleep problems because they are easily hyperaroused and find it difficult to get comfortable and settle for sleep. A child with this problem may become agitated with the bed sheets laying on their body or fuss with the way their pajamas feel. Sometimes the tactually defensive child falls asleep more easily if they have the body contact of a parent lying next to them, which in turn reinforces the child needing a parent to lie next to them to fall asleep. A 4-year-old boy named Sam had this problem. Ever since he was an infant, he insisted that his parents go through a series of bedtime rituals. First, his mother would give him a 15-minute massage and get him dressed, but only after Sam changed his night clothes several times before finding just the right one. This was followed by three bedtime stories with Dad. Mr. N. would then lay down next to Sam and sing several songs while Sam would shine his flashlight at the glow-in-the-dark stars on his ceiling. Mrs. N. would return to the bedroom and lay down next to Sam. He would fall asleep while twirling his mother’s hair in tight knots for almost 30 minutes. This routine took about 2 hours each night. Sam often reawakened in the night and wanted parts of the routine to settle him back to sleep. His parents eventually gave up and began taking turns sleeping in Sam’s room, but they remained exhausted by their child’s obsessive needs for settling that centered around his sensory and emotional needs.

Hypersensitivities to sound may result in the child having difficulty screening out noises in the environment to allow for sleep. The slightest noise agitates them or causes them to reawaken. The problem is aggravated when the household tends to be very noisy (e.g., several children in close quarters, the television on constantly) or full of activity. Children with hypersensitivities to sound often do well when provided with white noise (e.g., oscillating fan).

In rare instances, the child who is extremely hypersensitive may shut down and sleep for long periods of time because they are overwhelmed by stimulation. Some parents misconstrue the child’s need for sleep as simply a high need for rest. Ian, at 12 months, slept about 18 hours/day. When he was evaluated, we found that he was delayed in his developmental milestones, but that he was also severely hypersensitive to all stimulation. By decreasing the level of stimulation at home and keeping a calm environment for him, he became more interested in participating in activities and accommodated fairly quickly to a normal sleep–wake schedule. He quickly developed many skills, catching up in all areas except language. In another instance, 3-year old Courtney came home after 6 hours in day care and would take a 3-hour nap, then wish to go to sleep by 7:00 p.m., sleeping through to 6:00 a.m. She too, was hypersensitive to touch and was not only shutting down when she came home, but was becoming aggressive at day care, biting and hitting other children who came near her. Both sleep patterns and aggression improved with a program that included sensory integration activities to address her tactile defensiveness, calm-down areas at day care and home, and decreasing the number of demands at day care to participate in so many activities.

7.2. The restless child with ADHD who craves movement

Another type of sensory integration problem that may affect sleep is the child who craves vestibular stimulation, but becomes hyperaroused by the movement. Young infants with this problem love to be bounced vigorously, wish to be held and carried constantly, like to ride in the infant swing, and may fall asleep only if they ride in the car for long periods of time. Some young babies with this need for movement also like vibration. For example, one 9-month old would only fall asleep if he was placed in a laundry basket on the clothes dryer (with the heat turned off, of course). Many parents report how their child is gleeful when father comes home from work and can rough house or wrestle with them on the floor after dinner. Although the child needs vestibular stimulation, they become overstimulated by the movement and find the task of settling for sleep very difficult. Many times children who crave movement stimulation also like heavy proprioceptive input (e.g., climbing, pushing heavy objects, wrestling with a sibling). At 7 years, Joshua was a hyperactive boy who constantly moved and sought movement activities. If he wasn’t directed to do focused movement activities, such as riding his bicycle to get milk from the grocery store after school or playing soccer with his friends, he would become aimless, running up and down the stairs and whirling around the house, crashing into furniture and people. At nighttime, he was at his worst. After the bedtime routine, his parents would put him into bed, then after a few minutes, he would escape from the bedroom, run up and down the hallway, jump on his parent’s bed, and laugh loudly. Limit setting at bedtime was unsuccessful until it was coupled with a program of helping Joshua to get enough vestibular stimulation in the afternoon with slow movement and deep pressure activities after dinner.

7.3. Problems with attachment and separation/individuation

Some children struggle with falling and staying asleep because of problems related to attachment. Problems separating from family members can occur for several reasons. The child with an insecure or disorganized attachment will become anxious whenever they are alone and have to separate from people important to them during the day or night. The origins of the insecure or disorganized attachment need to be explored in order to properly address its impact on sleep. Oftentimes, the parent experiences conflicts around leaving their child, projecting fears related to their past. For example, one couple had tried to use the Ferber method (Ferber, 1985) (e.g., involves putting the child in bed drowsy, going into their bedroom after increments of crying to soothe them, then leaving the bedroom) with their baby but could not stand the crying and felt compelled to rush in immediately to console their baby. They found the crying so intolerable, that soon the child was sleeping in their bed, which lasted for the next 4 years. When I explored this with them, they revealed that each felt that they were abandoning their child, but for different reasons. When the mother was 8 years old, she had a sister who died from leukemia. The ghost of the sister seemed to loom over her parenting, affecting how she parented Danielle and her ability to allow her daughter space to leave her side and explore the world. She constantly hovered over Danielle, creating the feeling that there were constant dangers in the world around her. For example, she would not allow her to play at other children’s houses or go to birthday parties without her being present and within sight. The father was anxious about being left alone and needed to be surrounded by people and activity all day long. He was less open to exploring what it was about being alone that troubled him. By the time Danielle was 4 years old, she appeared to be a highly anxious, hyperactive child who needed to be occupied by her parents all of the time, unable to organize even a single play activity by herself. It wasn’t until Danielle was 5 years old and had been in psychotherapy for about 6 months that her parents were finally able to allow her to sleep in her own bedroom. At first her parents needed to constantly check on her to be sure that, she was safe in her bedroom. Mr. P. took to sleeping in a sleeping bag in the hallway for a while until he felt assured that Danielle was secure. Despite their anxieties about leaving her alone, they did not know how to play with Danielle and needed help in developing a healthy attachment to Danielle. It was difficult for Mr. and Mrs. P. not to constantly teach her or provide structured activities all day long. Emphasis in the treatment was placed on helping Mr. and Mrs. P. to understand the developmental task of feeling secure to sleep alone, the importance of gaining a sense of self and separateness from others for themselves and their child, and in learning how to negotiate normal boundaries of intimacy with each other. Addressing the parents’ difficulties in engaging with Danielle around developmentally appropriate and pleasurable interactive activities while helping Mr. and Mrs. P. develop their own security and separateness remained a major focus of treatment.

In another family, the mother had set up a video camera in her year old child’s bedroom to monitor the baby’s sleep and wakening patterns which was supplemented by an audio monitor. Although it was not readily apparent to the mother why she had done this, she was able to make the connection with a little intervention that the reason she had done this related to her early upbringing. When growing up, her parents often fought at night while Mrs. D. tried to sleep. When Mrs. D. was 6 years old, her father beat her mother in one of these late night fights and broke mother’s nose. Her mother gathered up the children during the night and moved them immediately to the grandmother’s home. All contact with her father was refused by her mother, but after a year, her father was killed in a car accident. Despite the violence in her home, Mrs. D. loved her father and was traumatized by these events and her loss. Throughout her life, she remained anxious about being alone and often suffered from insomnia. Needless to say, her background influenced Mrs. D. to feel that bad things might happen to her child if she was not constantly vigilant. Working to make both mother and child feel safe were important to addressing the sleep problem.

Sometimes parents who need to leave their children at a babysitter’s or day care during the day feel ambivalent about leaving their child to sleep alone at night, perhaps feeling guilty about leaving them for many hours during the day while they work. Other parents have strong unmet needs for intimacy that are fulfilled by their child. This problem was depicted by Lisa, an 18 month old. The pregnancy was accidental, but Mrs. B. decided to go through with the pregnancy because she had always wanted children. After she had Lisa, she and her husband adopted the LaLeche League philosophy, allowing Lisa to nurse whenever she wished and to sleep in their bed at night. By 18 months, Lisa was showing no desire to wean from the breast and insisted on nursing every 1.5 hours throughout the night. This problem was the reason that the mother sought help, largely because the constant interrupted sleep made it difficult for her to work at her job during the day. As the mother could not tolerate separating from her daughter and enjoyed the physical closeness at night, she encouraged her daughter’s sleeping in their bedroom. The bedroom was large so the parents equipped it with two king sized beds, placed side by side because Lisa screamed when confined to a crib. Containing Lisa during the day was difficult for the parents. For example, Lisa cried whenever placed in a car seat or play-pen. The nanny who took care of her began carrying and rocking Lisa most of the day despite her age. Mother was very anxious about allowing Lisa to separate from her side. She was also resistant to weaning Lisa because she enjoyed the intimacy with her child even though weaning might help Lisa to begin to sleep continuously through the night. Before mother could consider this, we began by focusing on separation games during the daytime to help both mother and child to tolerate moving away from one another in play (e.g., hide and seek). We also spent time talking about what being alone meant for both parents. Mrs. B. revealed that it was at nighttime that she felt anxious about being unloved and lonely, something she had felt for many years. She felt that her daughter comforted her at night and made her feel less lonely. Mr. and Mrs. B. explored how they were developing separate lives from one another, rarely doing things together as a couple anymore. Mrs. B. was reluctant to give up breast feeding and sleeping with Lisa but realized the importance of finding better ways of fulfilling her own needs for intimacy while providing good boundaries (e.g., this is your space and this is mine), setting limits, and appropriate expression of intimacy with her daughter (e.g., through child-centered play and other pleasurable games). Mr. B. welcomed the opportunity to become more involved with his daughter, both in taking charge of some of the child care activities, as well as finding enjoyable ways to play with Lisa.

Some children use the sleep situation as a means of controlling their parents by getting their parents to give them attention that they may not get during the daytime hours. When exploring sleep problems, it is useful to find out how the parents and child spend their waking hours together and the quality of engagement with one another. In one particular case, a 9 month old, Devon, had learned to control his mother both at day and night. When the mother called me to make the first appointment, she described her child as “the devil himself”. The problem first began around eating when 6-month old Devon would refuse to eat for his mother, compressing his lips and turning his face away from his mother. He ate well for the nanny, which caused mother to feel rejected by her baby. By 9 months, Devon began to fight off sleep, sleeping only 20–30 minutes at a time for a total of 6 hours per day. When he awakened, he would scream at the top of his lungs until his mother would come and hold him. He would gasp and hyperventilate so badly that his mother would take him out of the crib and hold him. Father could not stand the screaming and would go in and yell at Devon. His attempts to comfort his son made no difference. Devon would shake his head “no”, then he would lunge his body around in the crib, sometimes catapulting over the crib’s edge. In the end, the parents concluded that what he wanted was mother to go in to be with him. The parents had tried everything for Devon including the Ferber technique, finally resorting to using medications, starting with Benadryl and later Valium, all with a physician’s oversight. There was no beneficial effect from any of these medication trials.

In working with Devon and his mother, several things became apparent. Devon was an extremely bright and competent child who was on the verge of walking and talking at 9 months. He was highly vigilant, constantly looking around the room and extremely wary if approached by a stranger. Mrs. P. could play with Devon for short periods of time in a highly engaging way, but after about 10 minutes, she would need a break from playing with him, finding the intensity of the interaction overwhelming to her. Mrs. P. revealed that she had several miscarriages before having Devon and was enormously disappointed that she had a baby that was so demanding after trying so hard to conceive a child. Marital issues were an overriding factor, with mother feeling little support from her husband who tended to work long hours to avoid being around Devon’s screaming and controlling behavior. To make any changes in Devon’s sleep problems and the family dynamics, it would be important to address issues around attachment, loss and disappointment, and what control serves in this family. Getting attention in positive ways and learning how to engage in pleasurable interactions with one another would be an important direction for the intervention.

The case examples provided in this section demonstrate the wide variety of problems that can occur when sleep is an issue. Although there are some children where simple parental guidance is all that is needed, there are many other cases where the problem is highly complex. In such cases, intervention needs to address the child’s constitutional or developmental needs, the parent–child relationship, the parent’s own past history, and marital issues that may affect sleep.

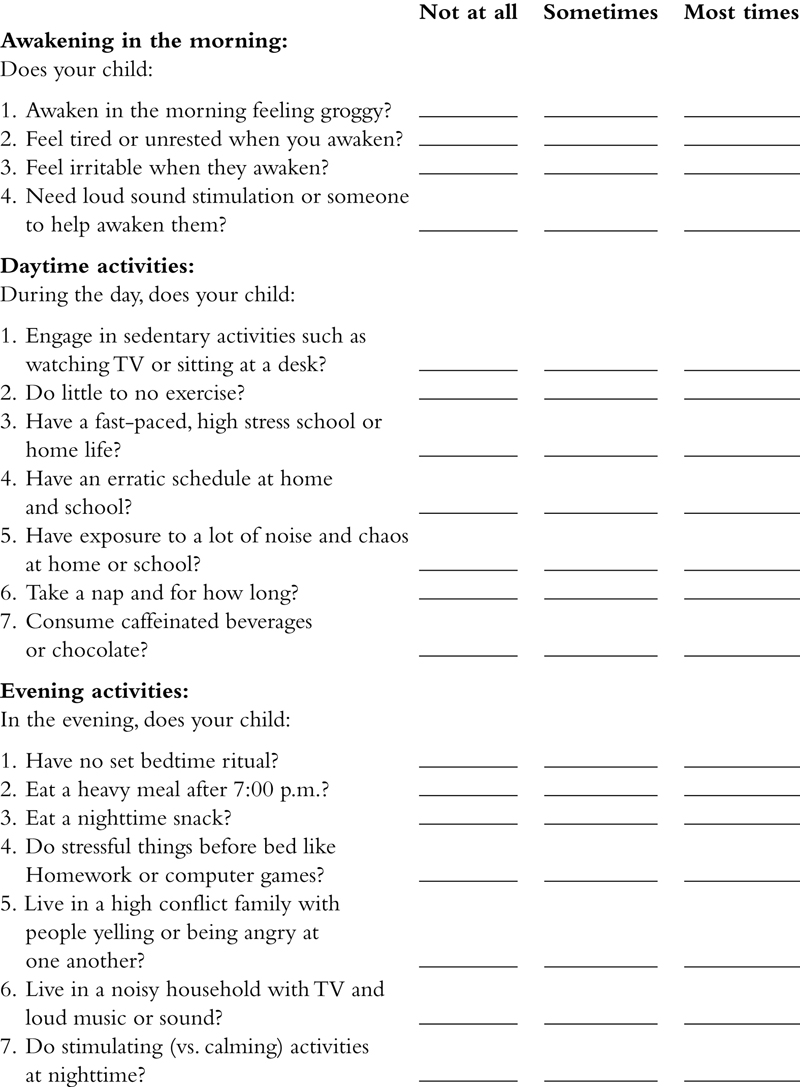

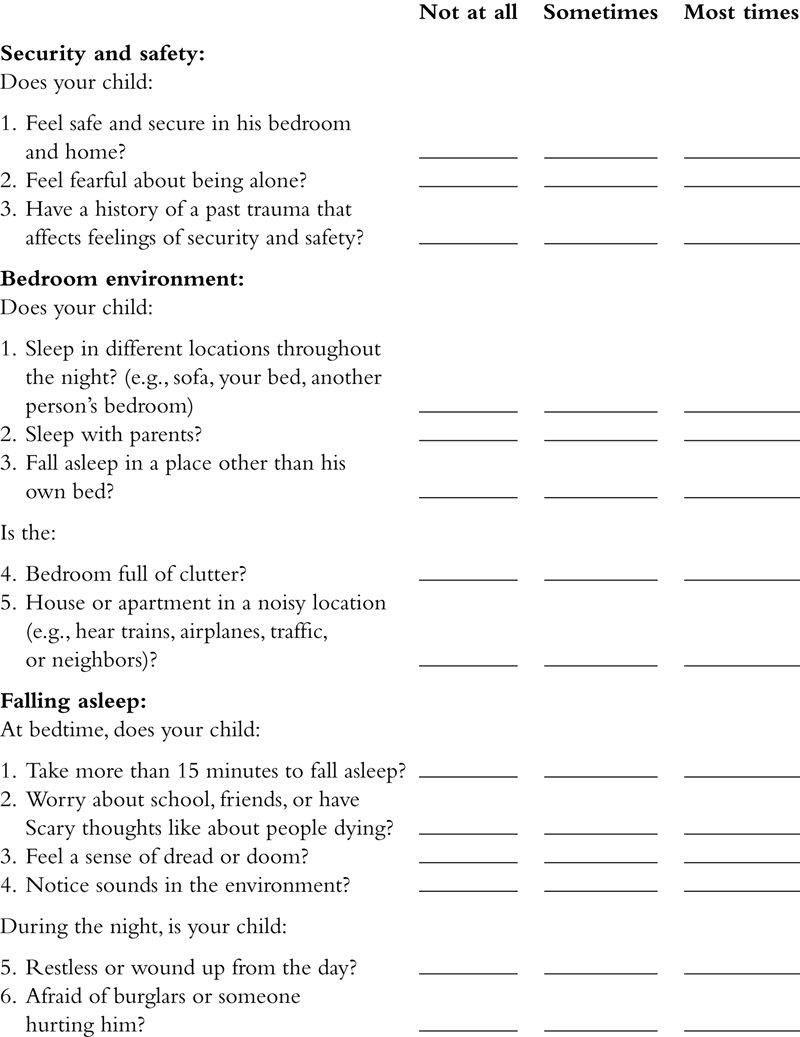

8. Evaluating sleep problems in the child

Evaluating the child’s sleep problems should begin with a comprehensive sleep history of the child. Later is a checklist of items that may be included in obtaining a history. In addition, a checklist is provided at the end of this chapter to help delineate the type of sleep disorder.

1. What time does the child awaken in the morning?

a. What is the morning routine?

b. What mood does the child have when he or she awakens?

c. Do the parents have to do anything special to arouse the child in the morning (e.g., body rub-down, several loud alarm clocks)?

2. What types of activities does the child engage in during the day?

How much time is spent in the following:

a. passive activities, such as watching TV?

b. movement experiences, such as playing outside on playground equipment or, in the case of the young infant, time in a stroller, riding in an infant swing, riding in the car, or rough house play?

c. learning activities and interactive play with the parents?

3. What types of demands are placed upon the child to separate from the parents during the day?

a. Are the parents both working?

b. Is the child in day care or with a babysitter?

c. How does the child handle separations from the parents in general?

d. How do the parents feel about leaving their child when they have to go out?

e. What do the parents do when they leave (e.g., say goodbye vs. sneak out the door hoping that the child won’t notice)?

4. How does the child handle transitions in activities and limits during the day?

a. Are there regular routines and certain scheduled activities at home, at day care, and so on?

b. Does the child like routines and do well with them?

c. Are the caregivers comfortable keeping routines and an organized life style?

d. Does the child become overly dependent upon routines and cannot vary from them?

e. Does the child need extensive warning when a routine will vary or when a new event will be happening?

f. How does the child respond to limits (e.g., tantrums if not given their own way)? How do the parents set limits on the child (e.g., does the parent warn the child that if they don’t behave, the boogie man will come and get them at night)?

5. How much stimulation occurs in the home or day care setting (e.g., number of persons in household, types of activity going on, noise level, closeness of quarters)?

a. How does the child respond to everyday stimulation (e.g., retreats to a corner, follows parent around constantly, takes a 3-hour nap when overwhelmed)?

6. Does the child nap and does it occur at a set time everyday?

a. How long is the nap?

b. If the child sleeps too long, does it disrupt the evening sleep pattern?

c. Where does the child sleep when he or she naps?

d. Does the child need help to fall asleep for the nap (e.g., bottle, being held)?

7. What is the evening routine like?

a. What is the bedtime ritual if there is one? Is it organizing for the child or does it cause the child to become overstimulated (e.g., rough house time with dad when he gets home from work, playing a computer game before bed)?

b. If the child has a nighttime snack, what are they eating (e.g., sweets, milk products, cola products with caffeine)?

c. Where does the child fall asleep? If he falls asleep in a place other than his own bed, do the parents take him into his bed later?

d. What time is the child put into bed and when does he actually fall asleep?

e. What is the bedroom environment like (e.g., colors, organization, where bed is located in room)?

f. How does the child fall asleep—for example, with parent’s help or by themselves?

g. What are the self-soothers that the child uses to fall asleep and which sensory systems do they involve (e.g., auditory-lullabies; vision-reading books; movement sense-rocking; touch-pressure—massage, warm bath, lying next to parent)?

h. Does the child behave differently for one parent over the other during the bedtime routine?

i. How does the child’s bedtime behavior affect the family?

8. Once the child is asleep, does the child awaken, how often, and what do the parents do when it occurs? For example, do they go into the bedroom and play with child, rock them, feed them, and so on?

a. How do the parents know the child awakens (e.g., use of monitor, parent is in room)?

b. What does the child do when they awaken (e.g., whimper, scream, play loudly with toys in room, shakes crib vigorously, dumps objects from dresser on floor)?

c. If the child cries, what does the parent think it means (e.g., the child is being abandoned)?

d. How does the parent feel when the child awakens (e.g., irritated, enraged)?

e. What does the parent do when the child awakens (e.g., Ferber method of ignoring for increments of crying)?

f. Do the parents awaken and find the child in their bed?

9. What are the sleeping arrangements? Do the parents sleep in the child’s bed, does the child sleep in the parents’ bed, or does the child sleep alone in a room or with other siblings?

a. How much sleep does the child get in the night (what time does he fall asleep and what time does he awaken in the morning)?

b. Does the child wet his bed? Does he get up in the night to eat or use the bathroom?

c. Do the parents feed the child a bottle in the middle of the night while the child is sleeping?

10. Does the child’s nighttime behavior disturb others in the family, neighborhood?

a. What restrictions need to be kept in mind in working on the child’s sleep problem (e.g., one parent has medical problem and needs child to be absolutely quiet, neighbors complain in apartment next door, other child awakens and then screams)?

b. Does the child’s sleep problems affect social situations, such as sleepovers with friends?

11. Does the child have bad dreams or nightmares? What about night terrors or sleep-walking?

a. Has the child ever done anything unsafe at night (e.g., gets up and watches X rated TV shows without parents knowing, leaves the house at night to go in back yard, cooks something on the stove)?

b. Does the child usually watch TV before going to sleep? Do the TV programs cause the child to become fearful or overly agitated?

c. Has the child seen scary movies that cause the child to be more fearful at night?

12. What is the parents’ own sleep history? Did they sleep with their parents?

a. What is their belief about children learning to sleep through the night (e.g., LeLeche League philosophy of family bed)?

13. Did either or both parents suffer any significant losses in their life (e.g., death of parent as a child)?

a. What was the parents’ first memory of being separated from their own parents? How did they handle it?

b. Do they have any sleep problems of their own and what are they related to (e.g., anxieties about work, depression, snoring, sleep apnea)?

c. If the parents have sleep problems, what do they do to help themselves sleep?

14. Are the parents comfortable being alone and what do they do with their time when they have an opportunity for aloneness?

a. Is the child ever left alone to play while the parents are nearby? Can the child play alone or are they constantly by the parents’ side?

b. Has the child ever been left with a babysitter or in day care? How does the child handle it?

15. Have the sleep problems changed over time? When were they at their worst?

a. What has worked in the past to help the child’s sleep problems? What has not worked?

b. What do the parents think will help now and what are they willing to try?

9. Management of sleep problems

The best way to approach sleep problems is to provide a program that addresses the sensory, emotional, and biological needs that help organize a person for sleep (see Skill Sheet #18: Strategies for improving sleep). Later is an outline of a comprehensive program for sleep management that encompasses these components. Marital problems and psychodynamic issues that the person brings to the process should also be explored when these affect the process. Suggestions for managing other sleep related problems, such as restless leg syndrome, sleep apnea, sleep-walking, sleep-related eating disorders, and night terrors are discussed in detail in the book entitled Sleep by Carlos Schenck (2008). Schmitt (1986) and Daws (1989) have also provided many helpful suggestions in addressing sleep problems.

1. Develop an appropriate sleep-wake schedule for the child and a bedtime routine that is predictable. Discourage daytime sleeping for more than 3 consecutive hours for a newborn and for more than 1.5–2 hours for toddlers or preschool-aged children. If the child is going to bed very late, move the bedtime back incrementally by 15 minutes each night until a suitable bedtime has been achieved. The goal is to have 7–8 hours of uninterrupted sleep during the nighttime hours.

2. Address sensory problems associated with high arousal (e.g., craving movement or exercise, restlessness, noise sensitivity, and tactile defensiveness). A sensory diet should be provided in a scheduled way including dimming lights, reading before bedtime, and listening to soft music. Movement activities are useful when provided in the morning and afternoon, avoiding vigorous exercise, rough housing, or intense movement experiences if possible after dinner. Linear movement activities, such as sitting in a rocking chair or a glider chair after dinner, are calming. Remember that movement activities help to burn off energy and satisfy a need for movement stimulation, but that they also increase arousal. Deep pressure activities, such as massage are especially useful in the evening. Sleeping with a body pillow and a heavy comforter on the bed can help inhibit the nervous system. Lavender scents in body lotions or in a warm bath are relaxing to the body. For children who are noise sensitive, an oscillating fan or sleep sound machine that provide white noise is useful. Noise-canceling headphones or ear-plugs can also be worn to screen out noise.

3. Evaluate if milk intolerance affects sleep. If the child is breast fed, the mother should be sure that she is not drinking or eating milk products that might affect the child’s sleep. Dairy products in the diet can impact sleep.

4. Engage in relaxing activities before bedtime. Some activities of this type include progressive muscle relaxation, contract–relax muscle activities, meditation, tai chi, and yoga (see Skill Sheet #8: Systematic Relaxation: stilling the body). Listening to hemisync music specially designed to slow the brain waves may be useful, A guided meditation tape is often useful as well. To help the child fall asleep, they should engage in deep breathing exercises, meditation to let go of anxieties, and other calming activities for the mind (e.g., counting backwards by increments, chanting, reviewing mindless lists) (see Skill Sheet #7: Mindfulness: stilling the mind).

5. Avoid stimulants and food that derail onset of sleep. Alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, and heavy meals should be avoided before bedtime. The liver is a light sensitive organ, therefore digestion shuts down as night falls.

6. Quiet the mind and release anything that might create anxiety before bedtime. The child should prepare for the next day’s activities, perhaps making a list of things to do, setting out clothing for the next day and tidying up from the end of the day. A sense of closure helps decrease anxiety. The person should avoid watching news programs and TV that might agitate them. Talk about soothing thoughts with family members and practice thought stopping and letting go of anxieties in meditation activities.

7. Parents with children should put their children in bed awake rather than drowsy or asleep. This should follow a predictable bedtime routine that both parent and child enjoy. A warm bath, stories, songs, hugs, massage, and holding a transitional object are some of the things that most children and parents enjoy in this ritual. The parents should limit the length of the bedtime routine and not let the child snare them into “just one more story” or “one more game”. Bedtime is not a play-time and should be differentiated as such. Developing boundaries and good routines with their children will help the child do the same for themselves.

8. Parents should develop a plan about how to cope with the children’s crying when it occurs at night and to demystify what the crying is about. Many parents feel that they are abandoning their child or think that their child is insecure and fearful. The child needs to sleep but may be overtired or want to play. Except in instances when the child is ill, the parents should let the child cry, and in this way, they help their child learn that this is a time to rest and that sleep will come naturally. Discourage the parents from projecting their own feelings onto the situation “Oh, you’re afraid of the dark, aren’t you?”

9. Assure that the bedroom environment supports sleep (i.e., oscillating fan, white noise, soft lighting, uncluttered space). When the child gets into bed, they may turn on some soft music, a rotating fan, or white noise audiotapes or a sound machine. The room should be reasonably dark and quiet and the television should be turned off. The child should not multitask in the bedroom (e.g., sit in bed and work on computer or use electronics).

10. Develop security in being alone during the daytime, as well as nighttime. Some people cannot be alone and have deep fears about abandonment. Others are fearful of burglaries at night or have fears of death or illness that emerge in the nighttime. Assuring that the home is safe and secure at nighttime is important. It is useful to address the roots underlying fears of being alone, fears, and insecurities at nighttime in psychotherapy.

11. The time between dinner and through the bedtime ritual should be organized and relaxing for the whole family. If the parents feel rushed or irritable because they feel pressured at night, their children will also feel this way. Changing the activity set of the entire household to prepare for bedtime is essential, beginning the calm-down cycle approximately one hour before bedtime.

12. It is very important that when there are multiple persons in the household that there is agreement on the philosophy of the bedtime program so that they can institute it. This is very important to avoid the possibility that one person might sabotage the child’s sleep program (e.g., parent is up at all hours cooking and doing noisy activities while children are trying to sleep).

13. If parents insist on sleeping with their child, it is important to address issues around separation or the presence of marital issues. Parents need to feel secure that they are doing a good job in putting their child to sleep. Reassuring the parents that some children are more difficult and need more attention and emotional security at bedtime is important. It is useful to explain to the parent that if they feel anxious, depressed, angry, resentful, or stressed, this will affect their children in feeling secure at nighttime. Many children develop anticipatory anxiety at bedtime when parents express these emotions. If the parents argue or there is emotional agitation and conflict in the household, it can cause sleep problems in all the family members. Likewise, if there are marital problems, they are apt to emerge in how the family organizes their bedtime scenario.

14. Do something mindless and unstimulating if the child awakens in the night. The child should not engage in something that will activate their mind and body, but instead a mundane task, such as counting backwards by twos or threes, making lists of countries of the world, doing suduko, knitting, or sorting cards. Drinking chamomile tea and sitting in a dimly lit room will prevent arousing the body to a fully awakened state.

15. It is often helpful to maintain a daily sleep log noting activities that were done during the daytime (e.g., sugar or caffeine intake, exercise, napping), the child’s mood, and the nighttime sleep schedule to help understand the child’s sleep rhythms and what has helped or not helped in the process.

16. Give the child a security object at bedtime to provide the child with comfort in the middle of the night should they awaken. Most children like a transitional object that they also use during the daytime hours, as well as a stuffed animal. Some children like having an object that “smells” like the parents (e.g., mother’s perfume). It is often helpful for the mother or father to carry the object with them and the child for a few days wherever they go to acquire importance as a transitional object and to get some of the scents of the parents. Some parents will sleep with the object for a few nights to give it their scent. Parents should avoid giving burp rags as transitional objects because they will signal the baby to want to eat.

17. Once the child reaches 6–7 months of age, use the Ferber method (Ferber, 1985) to address night wakings with increments of waiting before going into the bedroom to reassure the child. The program involves instituting a schedule of visiting the child when he wakes and begins a full-blown cry. The first night, the parents should go into the child’s bedroom after 5 minutes of crying. They may pat the child and reassure him but should not pick him up, rock him, or play with him. After he is settled, they should leave. The next night, they wait until 10-minutes of crying before they go in. Each night the length of time is increased by 5 minutes. This interval may be modified to smaller increments for some children who need a more gradual approach.

18. Discourage allowing the child to have a bottle to fall asleep or to have a middle of the night feeding (after 4 months of age). If the parents must feed their young infant during the night, they should give 1–2 ounces less of formula than they would during the day or the mother should nurse on only one side. When children are fed in the middle of the night, it becomes increasingly more difficult to eliminate this, as the child grows older. In addition, it is also important that the caregivers try to avoid giving the child cereal before bedtime in an attempt to induce sleep. There appears to be no relationship between feeding the child bedtime solids and induction of sleep (Beal, 1969; Deisher & Goers, 1954).

19. For children over 6 or 7 months, it is a good idea not to play or hold the child when they awaken unless the child is ill. The parents might leave the child’s room door open to help reduce nighttime fears. If the child awakens and is fearful, the parents may check in on the child and reassure him. If the child should become so upset that they vomit, it is best to throw a large towel over it rather than taking the child out of the crib or bed to clean the sheets. This way, the parent avoids lifting the child out of the crib and giving more attention to the distressed behavior. It is usually a good idea to remain in the room until the child calms down or has gone back to sleep if they have become extremely upset and are very fearful. If the child is old enough to understand the concept, the parent may encourage the child to “spray” out monsters in the room using a water or perfume spray bottle.

20. Use sedatives at night if other methods described previously have not worked. These should be prescribed by the person’s physician. Melatonin has been used successfully under physician guidance as a means of treating serious and chronic sleep disorders (Jan, Espezel, & Appleton, 1994; Jan & O’Donnell, 1996).

9.1. Separation games that help support sleep-suggestions for parents

As sleep is a separation issue, playing separation games during the daytime help both parents and child to become comfortable with the process. Later are listed some activities which can be modified depending upon the age of the child.

1. Playing disappearing games with objects is easier than having a favorite person disappear. Start with what is not so emotionally charged for the child. Hide favorite toys under sofa cushions, under tables, around the room threshold, and so on. Then encourage the child to find her “Big Bird.” You can hide and retrieve objects or make the game more elaborate by hiding the toy, then take the child outside the room for a few seconds with you, then run back to find the toy.

2. Play peek-a-boo around corners of rooms, from under blankets, and behind furniture. Also, play games that move from one room to another like rolling a ball and chasing it into the next room. Or play a “magic carpet” ride, pulling the child on a beach towel from one place to another in the house. Create spaces to crawl through like a big box.

3. Make a “good-bye” book with pictures of mom, dad, and baby; mom waving “goodbye”; mommy coming home, and so on. Use the book to read to him. The parents can give it to him when they leave him at the babysitter’s or at day care.

4. Many parents slip out the door to avoid goodbyes. Let the child see them get ready to leave. Ritualize the goodbye so that she can predict the routine. When leaving her at the babysitter, take some extra time so that it’s not a rushed time. The parents should be sure to have a reunion when they return, offering a hug and a kiss. The parents may practice saying goodbye and leaving for short periods of time while they do a brief chore (e.g., 5 minutes), gradually increasing the time that they are away.

5. Leave a “transitional object” (stuffed animal, keys, blanket) with him when the parents leave. The parents should carry this object with them and their baby when going places to attach special meaning to it. It becomes a symbol that they will come back.

9.2. Case examples

In this next section, three cases are presented that demonstrate different types of sleep problems and how they were treated using different approaches.

9.3. Case example of a long-standing sleep problem: when “nothing works”

Ms. T. was a 36 year old single woman who had wanted a child desperately and chose to become pregnant through artificial insemination. She first came to see me when her baby was 18 months old. Madison was a very competent toddler who experienced difficulties in self-soothing and separating from her mother. Although Madison improved temporarily in her sleep problems using approaches described in this chapter, it seemed that Ms. T. had difficulty following through on the treatment program. The Ferber method was one of the things that had been recommended, but Ms. T. found Madison’s screaming intolerable. According to Ms. T., nothing seemed to work but when I asked how long she tried any one technique, it seemed that consistency was a problem. Over the intervening 3 years, Ms. T. tried numerous different approaches to address Madison’s sleep problems. Ms. T. called me when Madison was 4 years old. She was desperate, feeling that she needed to solve Madison’s sleep problems because she was exhausted and unable to function in her job as a school teacher.

Ms. T. described Madison as a very sweet and loving 4.5-year-old child, yet she could be very demanding. She attended nursery school during the day and seemed to be doing quite well. Madison had a long daytime nap as soon as she got home from school in the afternoon. Due to the long nap, Madison would not be ready to fall asleep until 10:30 or 11:00 p.m. Madison would sleep alone in her bedroom as long as Mom would lie down beside her until she fell asleep. As Madison would call out throughout the night for her mother, Ms. T. decided to sleep on a trundle bed beside Madison’s own bed so that she wouldn’t have to get up and go into Madison’s bedroom in the middle of the night.

Once Ms. T. had begun to sleep in Madison’s bedroom, she could not break Madison of the habit. Madison would not sleep anywhere else except beside her mother. Not only that, she needed a constant supply of bottles throughout the night, sucking on a bottle while she slept. As soon as a bottle had emptied, she would awaken and want another bottle. Sometimes Madison would awaken and want something to eat and because Madison was a poor eater, Ms. T. would give her something, usually a sandwich or yogurt. To avoid getting up to get more bottles, Ms. T. would set out several bottles of juice beside Madison’s bed. During the night, Madison would call out because she couldn’t find a bottle or her stuffed lamb doll. She was often wet and couldn’t stand it, then Ms. T. would sometimes strip the sheets and change Madison’s pajamas. As a result of all these awakenings, Ms. T. felt that she was getting about 4–5 hours of sleep a night. By morning, the bedroom was filled with empty bottles. The sheets were soaking wet even though Madison wore diapers to bed. Ms. T. felt cranky and tired all day long and had difficulty working at her job.

After school, Madison would soothe herself by drinking from a bottle while watching TV. Ms. T. felt that the bottle was the only thing that would calm Madison down and help her feel less cranky and fall asleep. She tried getting rid of the bottle by using rewards and stickers, cutting down gradually, substituting plain water in the bottle and talking about the problem. Ms. T. was also concerned about the serious decay that was found on Madison’s teeth. Madison agreed that she needed to give up the bottle but found she couldn’t do it. Ms. T. also thought that if Madison did not get her afternoon nap, she would become overwrought and would have a huge tantrum. Apparently, other children had stopped coming over to play with her because she would need a nap and couldn’t play after school.

Madison was extremely demanding of her mother’s time and attention. Ms. T. found it hard to find time to do food-shopping, laundry, or clean the apartment. She resented fixing the bottles and was constantly washing diapers and wet sheets. The whole apartment smelled of urine.

Ms. T. felt that she, too, had difficulty separating from Madison and hated leaving her when she went to work. She felt exhausted and depressed and was on antidepressants to help her cope. As a young adult, she had a history of drug and alcohol abuse but claimed that she drank only occasionally in social situations. Ms. T.’s mother was an alcoholic and during Ms. T.’s teen years, her mother would yell at her to vacuum, cook, and clean to her satisfaction while she drank, then she would force Ms. T. to lie to her father that her mother was not drinking. It was clear that Ms. T. suffered from emotional neglect and codependency.

9.4. Evaluation findings

When I met Madison, I was struck by her waif like appearance. She appeared anxious about seeing me, but with urging, she was able to pick something that she liked to play with. She began playing in the doll-house, remaining silent except for occasional whispers in her mother’s ear. She wanted her mother to watch her solitary play. A scene was set up as if in slow motion. The dolls were eating at the table, but the same scene kept repeating itself. The table was set over and over again with cups and utensils, but food was never served to the doll family. The play was silent. Madison did not talk nor did her mother talk. After the foodless meal, she put the dolls to sleep. Soon every room in the house was filled with dolls piled high, one sleeping on top of another.

All of Madison’s play, centered around bodily functions of eating and sleeping and clearly, none of the characters could separate or differentiate from one another. When I tried to interject interactive play, Madison seemed overwhelmed, not sure what to do. Her play was just like her nightly routine—a story that kept repeating itself, but one where nobody’s needs got met.

A bit later in the session, I asked Ms. T. to leave the room for a few minutes to see how Madison could tolerate separating from her mother. Madison barely seemed to notice as her mother said good-by, seeming immersed in her drawing. When her mother returned, Madison told her that she was fine being alone with me. This was helpful information to see that Madison could feel safe and could separate from her mother, at least during her waking hours.

As I looked at Madison’s drawing of a person, I was struck by its composition. One could pick out arms and legs, but the trunk was a jumble of scribbles with no form. At this age, one would expect to see hands and feet, but there were none. Madison told me that she wished for an endless supply of cake and candy, but the worst animal to be would be a pig because it lies in mud. It reminded me of her lying in her own urine every night.

I asked Madison what she thought would help her sleep problem. She replied, “I don’t want to wear diapers anymore but I like the bottles because they taste good.” Here was an in-road to the intervention. Perhaps if I started by addressing her oral dependency needs, we might make progress. However, I sensed that her mother might resist them sleeping in separate rooms. I was also struck that the sleep problem and constant need for bottles were the predominant activity of home life.

It seemed that Madison was a competent 4.5-year old with many good developmental skills, but she seemed very passive in knowing how to interact with others. She had learned to control her mother with her drinking and sleep problem, a similar pattern that consumed Ms. T.’s own childhood with her own mother. It also seemed that Madison had a strong narcissistic need for oral gratification and didn’t have resources to self-soothe in age appropriate ways. Although Madison was quite capable of separating from her mother during waking hours, she insisted on her proximity at nighttime, largely due to her vulnerabilities in being able to self-soothe and her high need to control her mother’s whereabouts. At the same time, Ms. T. was having problems in separating from her child and in seeing how she and Madison were different people. The relationship between mother and child appeared symbiotic. I was concerned that Madison had a poorly developed sense of self. She was constricted in her ability to express emotions and her thinking and actions were dominated by her need to fulfill basic bodily functions. A good focus in treatment would be to help Madison learn how to assert herself, in age-appropriate ways while developing a stronger sense of adequacy before she would be able to overcome her problems.

9.5. The intervention

In our first parent guidance session, Ms. T. and I talked about how Madison’s sleep and bottle drinking problems were linked and how Madison was controlling her mother with her oral dependency and separation needs. Ms. T. appeared eager to embark on a therapy plan. I prepared her for the treatment by suggesting that Madison needed to develop other ways to self-soothe than to rely on oral gratification. She also needed appropriate ways to express control, emphasizing mastery of things that she could learn and do.

As Ms. T. had tried many approaches to help Madison without success, I felt that it was important to make the sleep problem seem even more intolerable for Madison in an effort to try to motivate her and her mother to change. On one level, it appeared that Madison and her mother were content with the status quo. The only thing that Madison was motivated to change was, wanting to get rid of the diapers. Since the bottle drinking was the underlying problem for the diapers, I suggested some strategies to focus on this problem. My first suggestion was to wake Madison every 2 hours to go to the potty, to change her diapers if wet, and to change her sheets if they were wet, making a production of the wetting behavior. Since she always wanted the bottles, I suggested that Ms. T. not provide bottles for her at bedtime, drawing a parallel between how an alcoholic will drink if served drinks all day long. Ms. T. was uncomfortable with my talking about Madison’s bottle drinking problem in this way. I suggested that if she wanted another bottle, Madison should take the last bottle downstairs, clean it and prepare another bottle. I stressed that she should not be allowed to go back to sleep until these tasks were done. Since traditional behavioral approaches had not worked in the past, I thought that a more symptom-focused approach like this may work.

Coupled with these suggestions, I recommended that Madison needed individual psychotherapy at least once/week to help her develop a better sense of self and identity, to become better at problem solving and coping, to learn to self-soothe in more appropriate ways, and to express her emotions both verbally and through play. Changes in the nighttime problems might not occur until Madison had better emotional resources for coping. I also suggested that Ms. T. receive therapy to help her in exploring why it was hard for her to separate from Madison and what would help her to function better in her own life.