Treatment of attentional problems is complex because there are many ways that attentional problems are manifested. In addition to inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, the child may show a range of developmental, emotional, and learning challenges, such as poor motor planning, low motivation, poor emotional regulation, and problems with sensory integration, language processing, and perceptual organization. Interventions need to address not only the core attentional deficit, but the accompanying problems that interfere with behavior and learning and how the attentional problem impacts social interactions. It is also important that different treatment approaches be modified or blended together depending upon the child’s age, developmental level, and overall needs.

A variety of treatment approaches have been used in treating children with attention deficits. Those that are more widely used because of their proven effectiveness include behavior modification techniques to address problems of impulsivity and behavioral control (

Bloomquist, August, &

Ostrander, 1991;

Cocciarella, Wood, & Low, 1995;

Goldstein & Goldstein, 1990), and cognitive training that emphasizes problem solving, organization, and self-monitoring skills (

Barkley, 1997;

Brown, 2013). Use of medication

to treat symptoms of ADHD is often helpful in reducing hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention, particularly when it is combined with parent training and therapy directed at improving the child’s self-control (

Horn et al., 1991). Other approaches that have been used include the following:

• Special education and tutoring to address learning needs,

• Language therapy to improve auditory processing,

• Sensory integration to address sensory problems that affect attention and activity level,

• Visual training and eye desensitization to improve eye focus,

• Auditory training (i.e., Tomatis, Berard) to decrease auditory hypersensitivities and improve auditory discrimination,

• Neurofeedback to improve attentional focus and decrease anxiety,

• Relaxation techniques for self-calming and body inhibition,

• Homeopathic medicine,

• Dietary supplements and dietary control of sugar intake.

Some of these approaches have limited success, such as relaxation techniques while others have not been fully researched to prove their effectiveness. Whatever approaches are used, it is generally accepted that most children with ADHD need a multidisciplinary approach that combines more than one type of treatment (

Blackman, Westervelt, & Stevenson, 1991;

Horn & Ialongo, 1988;

Maag & Reid, 1996;

Whalen & Henker, 1991).

What is striking about this list of treatment approaches is how they are focused primarily on working directly with the child with his or her attentional problems. Although it is important to address the core deficits that underlie attention in the child, the treatment must also include working with the child within the context of the parent–child relationship and the home and school environment. It is through this relationship that the child learns to self-modulate activity level, to integrate attention to both objects and persons, and to gain a sense of mastery and control.

This chapter will provide background information about the different types of attentional problems commonly observed in young children. The attentional problems of individuals with autism, attention deficits with hyperactivity, mental retardation, and regulatory disorders will be discussed. This will be followed by a discussion of the neurobiological bases for attention and executive functioning and a description of the process of attention. The foundations of attention—arousal and alerting—are discussed including their role in sensory registration and orientation and habituation to novel stimuli. Practical information will be provided about the impact of different types of stimuli on attention. The importance of selective attention and motivation and persistence will be described. Different treatment techniques will be presented to address the underlying problems that contribute to attention deficit, emphasizing the use of the child-centered therapy described in

Chapter 10 with cognitive-behavioral and sensory integration approaches. Finally, case examples of several children will be presented to illustrate the

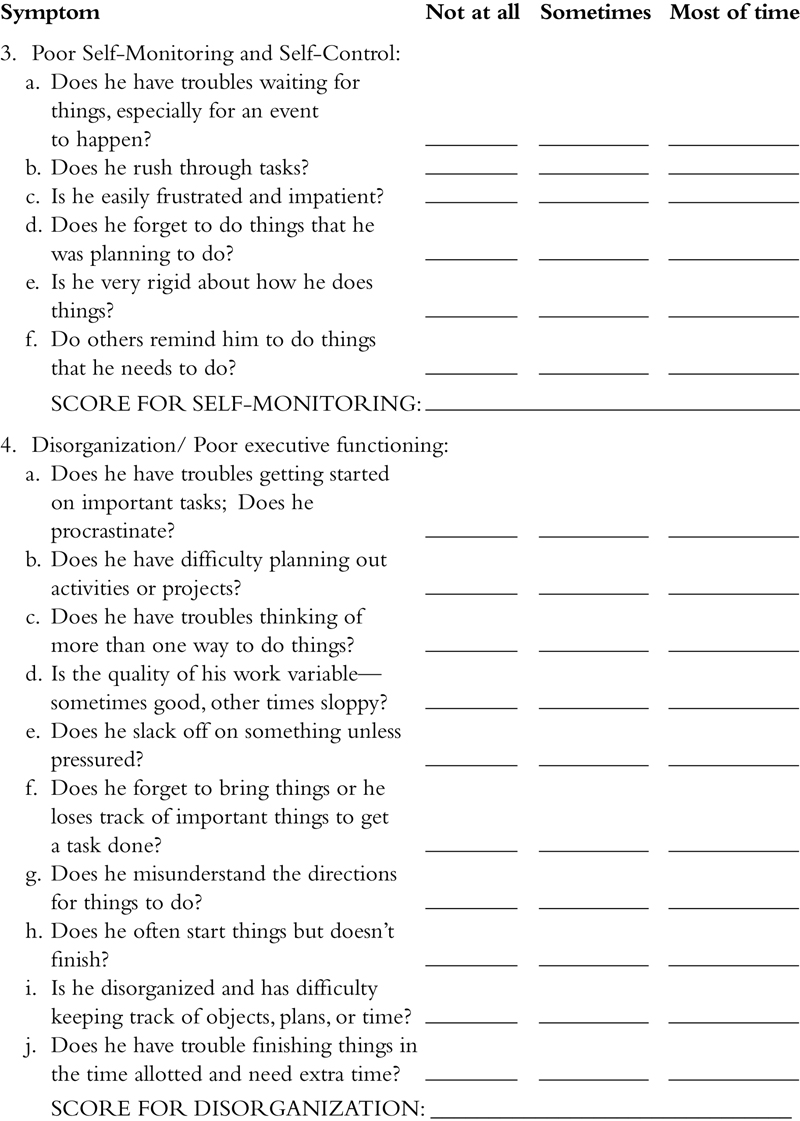

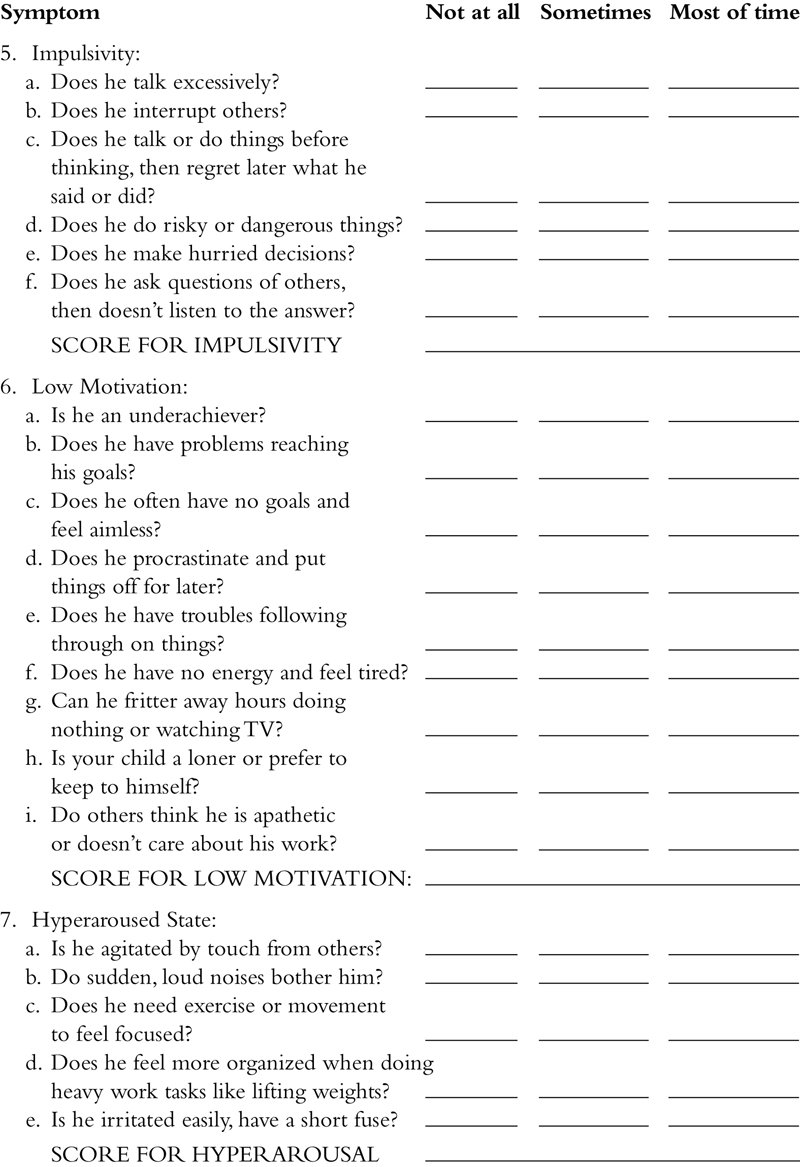

model, one of which focuses on a young child with ADHD, one that describes how ADHD affects the person’s view of self, and in a final case where the child lives with family members, all of whom have ADHD. A checklist is provided at the end of the chapter to assist in diagnosing the different types of ADHD in children.

1. Types of attentional problems

One of the “core” symptoms of behavior disorders, such as hyperactivity, learning disorders, and mental retardation is a deficit in attention. Attention deficit disorder has been described as a constellation of symptoms that includes distractibility; poor concentration and lack of persistence; poor self-monitoring; disorganization; and impulsivity (

Goldstein & Goldstein, 1990). In addition to problems with impulsivity and disinhibition, many children with ADHD have other associated cognitive problems that impact motor planning, verbal fluency and communication, mood regulation, motivation, and self-control (

Barkley, 1997,

2010). Prospective studies of attention deficit disorder have confirmed that children in this population are at high risk for academic underachievement and behavioral difficulties (

Carey & McDermitt, 1980;

Rutter, 1982). Persistent inattention in early childhood has also been associated with poor achievement in reading and mathematics in the second grade (

Palfrey, Levine, Walker, & Sullivan, 1985). ADHD appears to have a high comorbidity with a variety of psychiatric disorders (e.g., oppositional, affective, anxiety, conduct, and learning disorders) (

Pliszka, 1998,

2008), which may have different etiologies. When anxiety accompanies ADHD, it appears to increase impulsivity and predict that these children respond less well to stimulants. However, there appears to be a strong genetic predisposition to ADHD; therefore, diagnosing and treating family members, as well as the child with ADHD is important in developing the interventions that address the functioning of the child in the family environment and parent–child interactions (

Hechtman, 1996).

Epidemiological studies using standardized diagnostic criteria suggest that between 3% and 6% of school-aged children may suffer from ADHD (

Goldman, Genel, Bezman, & Slanetz, 1998). Using teacher-reported measures to examine prevalence, it appears that the rates for attentional problems vary depending on the type (

Wolraich, Hannah, Pinnock, Baumgaertel, & Brown, 1996). Studies have documented prevalence rates for children with attention deficit with hyperactivity (7.3%), ADHD with inattention (5.4%), ADHD with hyperactivity and impulsivity (2.4%), and ADHD, combined type (3.6%). This research suggests that children with ADHD are a hetereogeneous group, therefore, it is useful to discuss the different types of attention deficit in terms of the symptomatology that underlies the disorder.

Children diagnosed as having an attentional deficit do not always fit into well-defined categories with uniform characteristics. For example, an inability to attend appropriately has been associated with the diagnosis of mental retardation, schizophrenia, autism, hyperactivity, and learning disabilities. The etiologies of attentional disorders are many and often nebulous. Many researchers contend that the etiology is a function of neurologic dysfunction.

A. Impaired sensory registration is a common problem affecting attentional abilities. A pattern of overarousal is seen when there is difficulty filtering extraneous information. Accompanying this picture are orienting to irrelevant stimuli, distractibility, excessive motor activity, and a decreased attention span. In contrast, a pattern of underarousal may be manifested in two ways; (1) a high activity level associated with stimulus gathering behaviors, or (2) low activity level with difficulty orienting and acting upon novel stimuli. Research suggests that children with ADHD are likely to show somatosensory dysfunction (e.g., tactile defensiveness) (

Parush, Sohmer, Steinberg, & Kaitz, 1997), as well as developmental dyspraxia and problems processing vestibular input (

Mulligan, 1996). Some of the symptoms of impaired sensory registration that impact attention include the following:

1. Sensory overload in busy environments (e.g., classroom, malls, playgrounds).

2. Auditory hypersensitivities to certain sounds:

– high pitched sounds, such as whistles or children laughing,

– low frequency background noises from heaters or appliances,

– loud noises, such as vacuum cleaners, toilets flushing, or doorbells.

3. Visual distractibility with difficulty screening out relevant from nonrelevant visual stimuli and poor coordination of the eyes for focused work:

– difficulties converging eyes in midline for near-point work,

– overwhelmed by too many visual stimuli,

– need for clear spatial cues in environment (e.g., boundaries drawn around areas on blackboard).

4. Tactile hypersensitivities to certain types of touch:

– bump or push other children when in close quarters and bothered by random touch from others (e.g., playground activities or circle time),

– complain about tags in clothing; only want to wear certain types of clothing,

– may dislike face or hair washing and being hugged or patted by nonfamiliar persons,

– may become distraught with normal tactile input from the environment, such as the feel of the chair when sitting on it.

5. High need for proprioceptive input (weight, pressure, traction):

– like to pull and push on heavy objects (i.e., in play the child may crash trucks together),

– like to hang from jungle gym bars or bannister,

– like to butt head into things,

– prefer rough housing activities like pillow fights, wrestling,

– may love deep massage on back.

*Note that when the child seeks these things, they tend to be more organizing.

6. High need for vestibular movement activities:

– may love to swing high for long periods of time,

– like to move about, run, or find opportunities to move on playground equipment,

– often leaves desk at school to get something,

– when a child seeks vestibular activities, it is important to evaluate whether the child is benefitting from the movement or if they become more active by doing it.

7. Motor planning problems and executive functioning problems:

– difficulty initiating and planning new movement activities,

– prefer sameness in movement games,

– need physical assistance and verbal prompts to learn a new motor activity like shoe tying or skipping,

– procrastination.

B. Impaired information processing may be associated with attentional deficits, especially slow processing speed and memory problems. Difficulties in accurately identifying stimuli or detecting sensory information may be the result of an inability to sustain attention. The attentional deficit may result in the individual not orienting appropriately to novel stimuli (i.e., can’t find something in visual field), having difficulty with understanding meanings of things, and not organizing self in time and space for efficient performance. This inability to redirect attention to salient stimuli may result in an apparent behavioral perseveration. Concurrent with these problems may be deficits in information storage and retrieval necessary for learning. In addition, dyspraxia (e.g., disorder in planning and organizing adaptive motor responses) and executive functioning problems are often observed as well.

C. Inattention is commonly seen in children with ADD. Problems arise in the child’s ability to finish activities and follow through on directions, to give close attention to details, and to listen when spoken to. The child may avoid tasks that require sustained mental effort and lose things or forget to do daily activities. Difficulty organizing tasks and activities is evident. Children who show ADD without hyperactivity are less apt to have problems with conduct and impulsivity, but they are more likely to be withdrawn and anxious (

Quinn, 1997). Gender differences have been reported with some girls showing ADD but lacking the typical symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity.

D. A deficiency in behavioral inhibition is a component of the attentional disorder (

Schachar, Tannock, Marriott, & Logan, 1995). Behavioral inhibition is necessary for optimal sustained attention and appears to have a parallel in the autonomic nervous system (e.g., the lowering and stabilizing of autonomic activity) (

Porges, 1984). Problems with disinhibition or impulsivity are manifested by a number of different behaviors including the following:

1. Increased activity level:

– fidgetiness, difficulties remaining seated, and restlessness,

– high need for movement, such as running and climbing.

2. Poor impulse control:

– excessive talking,

– interrupting others,

– demandingness,

– inability to wait their turn or for events to occur,

– need for immediate gratification,

– respond too often and too quickly during tasks that require vigilance, waiting, or careful work,

– high need to touch things before thinking what are the context or task demands.

3. Difficulties making transitions in activities:

– resistance in changing from one activity to another,

– tendency to rush into next activity without thinking about the sequence.

4. High need for novelty coupled with a short attention span:

– get bored easily with toys or school work,

– do an activity only briefly then want to do something else.

5. Problems organizing and sustaining play:

– Once focused and on-task with game or activity, often cannot think of more than one thing to do with toy or game,

– Need help to elaborate on what they are doing,

– Difficulty taking in other people’s ideas (theory of mind),

– Difficulty processing another person’s social cues while trying to figure out what to do with the toy. Video games, surfing the Internet, and TV are often favorite activities because the child doesn’t need to integrate social-affective feedback from others in dynamic interactions.

E. Difficulties with executive functioning including problems in modifying actions and adapting to environmental demands are present when an attentional deficit is present. Behavioral responses are often stereotypic and perseverative in nature. Often, the child is bound by previously learned and explicitly taught behaviors. The ultimate impact of the attentional disorder is on development of communication, perception, learning, and social–emotional skills. Many children with ADHD have problems with motor planning and sequencing, verbal fluency, use of self-directed speech, and other executive functions that affect planning and organization of cognitive resources.

Barkley (1997) describes a model that suggests that the core deficit underlying ADHD is a lack of behavioral inhibition, poor self-control, and poor executive functioning. His model is very useful in understanding how executive functions are compromised when the child has ADHD. He stresses the importance of the child with ADHD in learning how to self-direct actions and to self-regulate.

In the following sections, hyperactivity, mental retardation, autism, and regulatory disorders are discussed in terms of their symptomatology related to attention.

1.1. Hyperactivity

Hyperactivity is a generalized symptom, which has been used to categorize a population of individuals who exhibit a lack of control of spontaneous activity. A diagnosis of hyperactivity is often associated with abnormally high levels of motor activity, short attention span, low frustration tolerance, hyperexcitability, and an inability to control impulses.

Several physiological models have been proposed to explain hyperactivity. The high activity level has been interpreted as a parallel of an overaroused or highly aroused central nervous system (

Friebergs & Douglas, 1969), as a compensatory behavior to raise the arousal of a suboptimally aroused individual via an increase in proprioceptive sensory input (

Satterfield & Dawson, 1971), or a correlate of defective cortical inhibitory mechanisms (

Dykman, Ackerman, Clements, & Peters, 1971).

Hyperactive children with attentional deficits have also been hypothesized to have deficiencies in cholinergic systems (

Porges, 1976,

1984). Studies have indexed cholinergic activity via the parasympathetically mediated heart-rate responses. There have been reports of heart-rate responses that are incompatible with sustained attention (

Porges, Walter, Korb, & Sprague, 1975). Heart-rate responses theoretically associated with sustained attention are mediated by the vagus and include slowing and stabilization of heart rate. The hyperactive child may have problems modulating the cholinergic systems and regulating parasympathetic activity. Thus, rather than observing a sympathetic dominance, the hyperactive child may have deficits in the regulation of autonomic function via the parasympathetic nervous system.

1.2. Mental retardation

The research with the mentally retarded is consistent with the view that sustained attention is a manifestation of central inhibitory processes. The attentional deficit in retarded individuals has been observed as slow reactions times, poor inhibitory skills (

Denny, 1964) and general deficits in attentional performance. This deficiency may contribute to the retarded individual’s inadequacy in obtaining relevant information from the environment to perform competently and may cumulatively contribute to deficient cognitive development.

1.3. Autism

Autism, a psychopathology associated with abnormal attention, has been characterized by an enduring failure to recognize and to respond with affection to others (

Kanner, 1943). The symptoms of autism have been grouped into five categories of disturbances: perception; motility; developmental rate; relationships to persons and objects; and language (

Ritvo et al., 1970).

Rutter (1966) has described an absence of response both to sound, which has often resulted in the autistic child being diagnosed as deaf, and to pain. The autistic child’s response deficit is generally manifested in a lack of responsiveness, but at times the

child may exhibit excessive or erratic responses (

Ornitz & Ritvo, 1968;

Rimland, 1964;

Rutter, 1966). Situations exist in which an autistic child who may appear deaf to loud sounds may suddenly overrespond, behaviorally and emotionally, to a soft distant sound with the appearance of extreme distress. Autistic children may also manifest abnormal stimulus selectivity where one stimulus is attended to while others are completely ignored.

Autistic children suffer a deficit along the dimension of reactivity. There is either a hypo- or hyperreactiveness to the environment. Research dealing with physiological correlates of autism has been inconsistent. However, certain relationships have been observed that are of theoretical importance in building the link between the physiological mechanisms mediating attention and autism. Autism my have a correlate in central levels of serotonin (

Boullin, Coleman, O’Brien, & Rimland, 1971). Serotonin is involved in reactivity to the environment. Since autistic children characteristically exhibit a hyporeactivity to environmental events, it might be predicted that autistic children have higher levels of serotonin than normal children.

1.4. Regulatory disorders

A common problem of children with regulatory disorders is an inability to develop self-regulatory mechanisms and a strong reliance on structure from the caregiver. The infant may be able to remain organized and focused as long as the mother or caregiver provides structure. Often one observes a very limited range of adaptable behaviors and a tendency to go from one toy to the next. Play behaviors tend to be repetitive with little diversity (i.e., banging, mouthing, or filling and dumping objects, rather than more purposeful play, symbolic actions, or interactive play). When presented with a challenging situation, the child may lack the problem solving to develop strategies to act effectively on the object. The child has a high need for predictability and structure in the environment and resists changes in routine or new challenges.

2. The processes that underlie attention

In young children, attentional processes operate on a continuum with basic arousal and alerting at one end and focused attention at the other end. Before one can be attentive, one needs to be aroused and alert, but too much arousal or alertness can hamper the capacity to attend. Arousal and alerting have evolutionary consequences, apparently evolving to mobilize the organism in response to survival challenges. Without the ability to attend, we would not be able to filter out irrelevant information, to tune into important elements in the environment, to process new information for learning, and to engage in purposeful activity.

Attention can mean many things including the following:

• basic arousal and alerting,

• habituation when a stimulus is no longer novel or relevant,

• interest in novel stimuli,

• screening and selection of information from the environment,

• motivation, persistence in remaining on-task or sustained processing of information, and

• self-monitoring and control of behaviors.

Persons can alert to stimuli in a variety of ways. For example, the alerting response may occur at a reflexive level, such as turning of the head to a loud noise. This occurs in many everyday settings when there is a sudden change in background noise (e.g., something is dropped, a door bell or phone rings, a car or truck makes a loud noise).

Knowledge that the alerting response may be reactive to a critical sensory threshold can be useful in therapy for an individual with hyporeactive sensory systems who underrespond to stimulation. This is used in therapy when a new sensory challenge is introduced. For example, a child swinging slowly forward and back in a hammock may experience a decrease in arousal level, but if the therapist introduces irregular and quick movements in a pretend “storm,” the child’s arousal level increases and he is forced to respond. In contrast, a child who is easily overstimulated by environmental noise (i.e., refrigerator hum, children playing), unexpected touch from others, or visual stimulation may become so overwhelmed by certain everyday experiences that they cannot function unless provided with regular calming activities.

If a person is underresponsive to sensory information and overlooks important details, it is useful to highlight salient information in the environment to improve alerting. For example, Megan was absent-minded and lost important things that were right in front of her nose. She needed to put up post-it notes throughout the house to remind her of things to do and routinize where she put important objects like her backpack, homework, or shoes.

At the other end of the continuum of attentive processes, there is selective sustained attention. This is related to what we seek to learn and the stimulation that we screen out because it is unimportant to us. Developing good selective sustained attention is something that can be learned but is certainly supported by a well-functioning nervous system. For example, some people have an unusual capacity to concentrate on difficult tasks even when they are in a very chaotic and noisy environment. We sometimes see this in young children who give us a “deaf” ear when watching cartoons because they choose to screen our demands out. This skill can be very adaptive if living in a hectic household or noisy school environment.

Arousal and alerting responses are often regarded as passive and involuntary. However, manipulating the importance of specific stimuli may result in changing the alerting capacity of a given stimulus. For instance, a new mother who was once a heavy sleeper may find that she awakes easily when her young infant whimpers. The infant’s cries no long elicit startle or defensive images, rather they serve to orient the mother to the needs of her infant.

In order to actively attend and learn new information from the external environment, an individual must be awake and alert. When an individual experiences sleep deprivation, both mental and motor functions decrease in their efficiency. Some individuals need to use external stimulation to alert themselves and to raise their arousal levels in order to attend to new and difficult tasks. We see this in everyday situations when people need their coffee before they sit down to work. But what happens when the person is over- or underaroused and cannot modulate arousal for efficient attention and learning? This is one of the problems that will be addressed in this chapter.

Since there is a limited capacity for attention, it becomes necessary to screen out irrelevant information. We have all experienced the need to close the door, tell everyone to be quiet, and clear our desk of debris before we can concentrate. This ability to screen out information and select what is important for attention is crucial for efficient information processing.

Another component of attention that affects learning is the amount of effort expended while sustaining attention. Motivation or persistence will vary considerably based upon prior learning and specific task demands. A person with an aptitude for math may be motivated to read technical books about abstract algebra, but have little patience for reading a mystery novel. Likewise, when task demands are high and the individual must learn a great deal of information in a short period of time, such as in a lecture on a complicated topic, the person becomes mentally fatigued after a short while and may begin doodling instead of taking notes to try to raise their arousal level.

3. What is attention? Some historical perspectives

The term “attention” is used commonly in education, psychiatry, and psychology; however, it is often vague and poorly defined. It often implies some type of internal or cognitive process. Attention is often used either to describe the active selection of information from the environment or the processing of information from internal sources. Selective attention may be observed when a person is looking for an approaching friend in a crowd of people. Internal attention can be anything from attention to one’s own thoughts to attention to visceral cues (i.e., feeling thirsty).

The notion that there are different psychological processes associated with the process of attention is not new. Even William James, the first American psychologist, emphasized this point.

Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought... It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others, and is a condition which has a real opposite in the confused, dazed, scatterbrained state. (James, 1890, p. 203).

William

James (1890), in his writings, distinguished between two broad categories of attention:

passive-involuntary and active-voluntary. Passive-involuntary attention was

defined as immediate or reflexive and related only to objects that directly affect the sensory systems. For example, touching a hot stove would elicit passive-involuntary attention. Active voluntary attention was associated with the concept of interest and was assumed to be directed toward objects perceived via the senses or toward ideational or symbolic objects. Active voluntary attention may involve purposeful activity that is either observable (i.e., engaging in a task), or a thought process (i.e., planning what to do next).

In order for an individual to attain functional competence, it becomes crucial that attention to ongoing routine sensory stimulation be passive and involuntary. When an individual is constantly attending to things like the feel of clothing on his body or the constant drone of a fan, there is little reserve for active voluntary attention to more meaningful environmental events or internal thoughts. When a person is actively engaged in voluntary attention, functional purposeful activity and learning can occur.

4. Arousal, alerting, and sensory registration

Arousal may be viewed as behavioral or physiological activity that is dependent upon changes in the central nervous system. Levels of arousal operate on a continuum from extreme alertness, to drowsiness, to deep sleep. Depending upon the person’s level of arousal, they will respond differently to sensory stimuli. Thus, we may be more reactive to a given stimulus while in an alert state than in a sleep state. Alerting, on the other hand, is the process of increasing arousal level. For example, a person who feels drowsy would be alerted by a loud noise. In classroom settings, optimal attentive behavior may be maintained by appropriate alerting stimuli (

Meldman, 1970). These will be discussed in detail in the treatment application section of this chapter.

Arousal: Arousal level parallels the behavioral states that we experience. For most of us arousal tracks a 24-hour day–night cycle (i.e., a circadian rhythm). During a night’s sleep, a person normally alternates between periods of slow-wave sleep without rapid eye movements (NREM) and desynchronized, fast activity REM sleep. Slow-wave sleep reflects a lower arousal level than REM sleep. Spontaneous awakening occurs usually after the individual has cycled through all stages of sleep but may also occur when a sensory stimulus is intense or cognitively meaningful is introduced. For instance, a phone or alarm clock ringing is intense stimuli that awaken most people. However, a barely audible stimulus, such as the floor creaking may awaken a person in heavy sleep who is suddenly wary of a possible intruder.

Alerting and sensory registration: Alerting is the process of shifting arousal states when presented with more intense or novel stimuli. The transition from waking to an attentive and alert state is dependent upon sensory registration. This basic central nervous system process prepares the individual to respond to incoming sensory stimuli. In sensory registration, the initial response to the sensory stimulus may be unconscious or conscious. For example, our bodies register basic sensory characteristics about the environment (e.g., temperature, light) on an unconscious level. When incoming sensory inputs become conscious, we alert and attend to them. In order for perception of a stimulus to occur, there is an internal process of scanning memory for a sensory match or mismatch. Sensory registration of stimuli plays an important role in the degree of alertness or wakefulness and the individual’s capacity to respond. One major aspect of sensory registration that relates to the attentional process is the orienting reflex. In the next section, the orienting reflex will be described.

4.1. The orienting reflex or the “what-is-it?” reaction

The orienting reflex is essential for survival. It is an important mechanism for attention to novelty. In other words, it alerts us to changes in our sensory environment. Once the orienting reflex is elicited, we may decide whether we need to act upon the stimulus. Orienting reflexes are elicited to mild and low intensity stimuli. However, when a very intense stimulus is presented, a defensive reflex is elicited. The primary difference is that an orienting reflex will disappear after repeated presentation (i.e., habituate). In contrast, a defensive reflex is very resistant to habituation. For example, we might rapidly habituate to the noise of young children in our homes, while we would never habituate to the sound of gunshots.

Early discussions of sensory registration and arousal mechanisms may be traced to

Pavlov (1927). He described the orienting reflex as the “What-is-it?” reflex that brings the organism closer to the source of stimulation.

As another example of a reflex which is very much neglected we may refer to what may be called the investigatory reflex. I call it the “What-is-it?” reflex. It is this reflex which brings about the immediate response in man and animals to the slightest changes in the world around them, so that they immediately orientate their appropriate receptor organ in accordance with the perceptible quality in the agent bringing about the change, making full investigation of it. The biological significance of this reflex is obvious. If the animal were not provided with such a reflex its life would hang at every moment by a thread. In man this reflex has been greatly developed with far-reaching results, being represented in its highest form by inquisitiveness—the parent of that scientific method through which we may hope one day to come to a true orientation in knowledge of the world around us (Pavlov, 1927).

The orienting reflex is not always associated with investigatory behavior, but may be related to reactive involuntary attention to changes in stimulation (

Sokolov, 1963,

1969). This may range from a reaction to a change in room temperature to the dimming of light in the room. The orienting reflex, according to Sokolov, is the first response of the body to any type of stimulus and functionally “tunes” the appropriate receptor system to ensure optimal conditions for perception of the stimulus. For example, a person’s ears may prick up in order to hear a person whispering an important message.

When the orienting reflex is elicited, all activity is halted, thus allowing the individual to prepare for necessary action. As the person's body stills, the body senses have an increased sensitivity which allows them to respond adaptively to the type of stimulus that is experienced. If the stimulation is intense, the nervous system seeks to dampen the stimulus’ intensity. If the stimulus intensity is weak, yet is meaningful for the individual, the organism will work to increase its intensity (i.e., pupil dilates to increase the light influx).

The orienting reflex has both behavioral and physiological components (e.g., heart rate change, head turning, EEG activation) that occur in response to introduction of a novel stimulus. The primary behavioral component is the “orientation” of the receptor organs of the primary senses toward the source of stimulation. The initial movement of the head to facilitate audition and vision is followed by the suppression of a bodily movement to reduce the background auditory noise and to increase the visual acuity. One might then observe investigative approaches toward the stimulus (e.g., reaching) depending upon the meaning of the stimulus to the individual.

Sokolov (1963) distinguished the orienting reflex from what he labeled a defensive reflex. Just as the orienting reflex “tuned” the organism to enhance the perception of the stimulus, the defensive reflex functionally raised perceptual thresholds. The ultimate aim of the orienting reflex is to increase receptor sensitivity. However, if the stimulus reaches the critical level of intensity associated with pain, the defensive reflex develops. The defensive and orienting reflexes are generalized reactions and not limited to any specific sensory system. They differ in their ultimate objective: the orienting reflex brings the organism in contact with the stimulus, the defensive reflex limits the impact of the stimulus on the organism. The orienting and defensive reflexes are often distorted in many clinical populations with atypical sensory processing. Consider, for example, the child who is underresponsive to touch, who is slow to orient and responds only to intense tactile inputs. This child would have a weak orienting reflex while at the same time, a strong defensive reaction to tactile stimulation. Children with this problem sometimes seek intense tactile input (i.e., bump or hug other people too hard) but also respond inappropriately to painful and intense tactile stimulation (e.g., laugh or ignore it). Consider the child who is hypersensitive to movement. There is both a strong orienting and defensive reaction. This child would orient to even the slightest bit of movement and would attempt to minimize the impact of vestibular stimulation by remaining close to the ground, fixating the trunk and neck to keep the body as still as possible, and perhaps closing the eyes to eliminate vision as a vestibular receptor.

4.2. Habituation and interest

One salient characteristic of the orienting reflex is that it habituates (i.e., the subject stops responding to the stimulus) over repeated presentations. Habituation has been generally defined as a decrease in responding after repeated stimulations. Dishabituation is when attention is redirected to the stimulus after there has been a change in the nature of the stimulus. For example, you may orient to the sound of the clothes dryer when it is first turned on. Very shortly, you habituate and you are no longer aware of the sound. But, suppose a coin falls out of a pocket as the dryer is running. Now the sound of the dryer has changed and you dishabituate and orient. If you are intensely interested in what is causing the new noise, you will take longer to habituate to the new sound. If you are unconcerned with the sound, you will rapidly habituate. We would be able to tell how important the stimulus is to a specific person by evaluating the intensity and duration of the person’s orientation toward the stimulus. In fact, this is one of the explanations for the basis of the polygraph examination. In the polygraph test, physiological indicators of orienting, such as electrodermal responses (i.e., Galvanic Skin Response) provide information regarding the importance of specific questions. Habituation is an important process for adaptation to the environment. It reflects a basic process of ignoring irrelevant stimuli and selecting stimuli that are important for survival and thus, require immediate attention.

We can derive a great deal of information about an individual by learning about the specific stimuli that cause them to orient and show interest. For example, a child who does not orient or register a sensory stimulus that most individuals would normally attend to would be considered underreactive. In such a child, a much more intense stimulus would be needed to elicit orientation and interest, such as a loud alarm or blinking colored light display. Lack of orientation may also be because the stimulus is too complex or too simple. Sometimes one observes a child with cognitive delays who appears totally disinterested in a particular activity. This may be because the child has been looking at the same toy for the past hour or has seen it everyday for the past 3 months and is no longer interested in it. It could also be that the toy is too complex for the child’s cognitive level or the characteristics of the toy do not present enough sensory information for him to process its features.

Failure to habituate, therefore, may be because the individual is responding to unimportant stimuli, is not encoding relevant information for learning, or the stimuli are poorly matched to the individual’s cognitive and sensory needs. In essence, there is a defect in the orienting reflex system. Lack of habituation usually occurs when the cerebral cortex has been destroyed or suffered extensive damage. Problems with habituation are often observed in individuals with senile dementia, severe mental retardation, and certain types of schizophrenia.

4.3. Role of stimulus characteristics in attention

We are most interested in objects, people, events, and tasks that provide novelty, complexity, conflict, surprise, and uncertainty (

Berlyne, 1960,

1965). These types of stimuli, if distinctive and unique in relation to what we already know, cause us not only to orient, but to remain interested for learning. The more novel, complex, and interesting the stimuli are, the longer it takes to habituate to them. We habituate quickest when the stimulus is familiar, weak, very brief or long in duration, or presented in quick

succession. This is true for any type of sensory stimulus—tactile, vestibular, auditory, visual, smell, or taste.

The process of selective attention is intimately related to lower brain structures (e.g., reticular activating system), which filter sensory input and modulate arousal states. Processing of inputs at the cortical or conscious level can only occur if there is widespread inhibition of unrelated cortical and subcortical activity. Thus, we can learn new information from the environment more efficiently when we can effectively screen out irrelevant stimuli.

4.4. The neuronal model

Sokolov (1960) proposed a “neuronal model,” which addressed how stimulus characteristics were stored in memory during attention. Sokolov proposed that the orienting reflex was not merely a response to current stimulation. Rather, he proposed that repeated presentations of a stimulus produced a neuronal representation. Typically, we need to experience a novel stimulus several times before we can understand and remember it. Information regarding stimulus intensity, duration, quality, and order of presentation are transmitted in a neuronal chain. Since incoming information is neuronally encoded on many different dimensions, it is possible to evaluate the characteristics of a stimulus to determine whether it has been previously experienced and stored in memory or is novel.

When a novel stimulus is introduced, the nervous system searches for a match or mismatch between the current stimuli and those already in the individual’s memory stores. If there is a discrepancy between what is currently experienced and prior memories (i.e., neuronal representation), the orienting reflex is elicited. The individual experiences a “This is new. What is it?” phenomenon. The orienting reflex will also occur if the stimulus is meaningful or important. In this case, the individual experiences, “I know this. It is important, and I need to respond”.

4.5. Neurobiological mechanisms responsible for arousal and attention

The reticular formation is the key structure for arousal for all of the senses except for smell. The thalamus (intralaminar nuclei) also receives information from the anterolateral system that processes pain, light touch, and temperature and is thought to play a role in arousal. The hypothalamus’ role in arousal lies with regulation of basic homeostasis and autonomic responses, such as heart rate and respiration when the person is presented with novel stimuli. When the person is aroused, the reticular system can be activated either by sensory registration or the person’s motivation to do something. For example, people can raise their arousal level by surrounding themselves with bright colors and light, or loud music with irregular rhythms. They can also increase their arousal by thinking about an upcoming, exciting event.

Wakefulness and sensory registration are regulated by the central core of the brainstem. An increased state of alertness is controlled by the thalamic or upper portion of the reticular formation along with nonspecific nuclei of the thalamus and diffuse thalamocortical projections. This area is affected by sympathetic activity of the nervous system and adrenalin. This is why individuals can increase their state of alertness through movement, tactile activities, or by ingesting doses of caffeine.

Broad areas of the cortex are alerted during arousal, but other parts of the cortex must be inhibited to allow for selective attention and orientation to specific sensory stimuli. This is accomplished through both cortical inhibition and feedback via cortical-reticular formation connections. In persons with ADD, it is not uncommon for them to feel flooded by competing ideas, random thoughts, or sensory distractions (e.g., noticing sounds in the environment when trying to concentrate). This is because they have difficulty inhibiting cortical feedback and reticular formation activity that does not relate to the task at hand.

Sensory registration and orientation to sensory stimulation including smell, taste, touch, and interoception are mediated by the limbic system, which includes the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus. The limbic system registers qualitative aspects of a sensory stimulus rather than precise discriminative sensory information, such as specific object traits. The hypothalamus and limbic system play an important role in things like feeding, fight or flight, mating, and emotion-provoking situations. These structures also help regulate homeostatic functions necessary for self-preservation and approach and withdrawal. This is the part of the nervous system that is affected in individuals with distorted sensory regulation systems (i.e., sensory hyper or hyposensitivities). For example, the hyperreactive person may perceive touch from others as highly aversive and too arousing. He might avoid physical touch from others and may associate negative emotions with affection or physical contact.

One of the limbic system’s roles is to modulate, dampen, and regulate fluctuations in attentional responses by coordinating autonomic, somatic, and behavioral responses. For example, during a demanding and novel attentional task, our heart rate usually quickens, but our motor activity quiets, thus maintaining a level of arousal in one system that is balanced with inhibition in another to allow for optimal learning. The limbic system helps discriminate objects in time and space. It processes novelty, change, and inconsistencies in stimulus features. It is concerned with pleasure-pain, immediacy, approach-avoidance, and fight or flight. It also helps in discriminating what properties of a given stimulus are shared with others rather than processing the specific properties of objects (e.g., texture, shape).

The hippocampus has several important functions. It helps maintain attention, compares new sensory inputs with stored information, aids in storage and retrieval of memory stores, and inhibits the reticular formation when a stimulus is familiar. The hippocampus is sensitive to intensity gradients (e.g., loud/soft, strong/weak, fast/slow) and also facilitates transmission of afferent input to the amygdala. When the hippocampus is damaged, the individual will have difficulty detecting and differentiating novel and familiar stimuli, may be slow to habituate, and will have a strong preference for familiar activities. The person may have a strong dislike for change and need routines to be the same, engage in ritualistic kinds of behaviors, be overattentive to irrelevant stimuli, or resist exploring new things. This type of person may need many repetitions before they can respond appropriately to a new situation or activity and typically it takes them longer to generalize newly learned skills.

The amygdala is a forebrain structure in the temporal lobe containing many nuclei that interconnect with the hypothalamus, hippocampal formation, and thalamus. The amygdala registers and synthesizes incoming novel sensory inputs and has a role in cessation of motor activity, thus playing an important role in both arousal and on-task attention. When the amygdala is damaged, the individual is apt to have problems arousing to novel stimuli, and integrating appropriate emotional responses to sensory inputs, usually overresponding. They may not be able to sustain on-task attention and tend to be hyperactive or restless, and they may show fear or anxiety in novel situations. When there are combined lesions of the hippocampus and amygdala, the person often has memory problems and amnesia similar to that observed in patients suffering from Korsakoff’s psychosis.

5. Sustained attention: attention getting and attention holding

In this next section, the process of sustained attention will be described in detail. Sustained attention is the ability to direct and focus cognitive activity on specific stimuli. Focusing of attention occurs in many ways in everyday life. For example, we sustain our attention to complete planned and sequenced actions and thoughts, such as following a recipe, reading a map, organizing a social event, interacting socially, or writing a report. We know how difficult it is to conduct these activities when there are continuous interruptions, such as the phone ringing or a demanding child at your side. Each time we are interrupted, we must redirect our attention and think, “Now, where was I?”; sometimes retracing our actions to be sure that we resume our attention and behavior in the proper place in the sequence. Often after an interruption, we need to rely on contextual cues to redirect our attention properly. For example, baking soda sitting on the counter may trigger the memory of whether we had already put it in the muffin batter.

Imagine the life experiences of a child who is continually experiences interruptions or distractions from internal and external stimuli. This child will have great difficulty in maintaining a state of sustained attention. For example, the child with low thresholds to tactile stimuli may be constantly orienting his attention toward the sensations associated with clothing touching his skin.

The ability to sustain attention is a necessary requirement for information processing. Without this basic ability, the child will have enormous interference in developing

cognition. Although there have been numerous theories and definitions of attention, the process of sustained attention can be categorized into three sequential operations. These involve attention getting, attention holding, and attention releasing (

Cohen, 1969,

1972).

Attention getting: Attention getting is considered the initial orientation or alerting to a stimulus. In a young infant, it can be observed in head turning toward a large, bright object presented in the periphery. In young infants, the types of objects that get their attention are the human face, bold patterns, motion, large objects, or loud sounds. Although the characteristics of objects or faces help to elicit attention, the young infant is very active in responding to these stimuli. The attention-getting process is very similar to the earlier discussion of the orienting reflex. However, unlike the orienting reflex, attention getting involves an active voluntary dimension. Similar to the orienting reflex the attention-getting response is related to the qualitative nature of the stimulus. The dimensions of stimuli that are attention getting vary according to past experiences. We know our individual reactivity to sensory stimulation and the dimensions of both external and internal stimulation that are important to us. For example, a person who is hungry will orient to the smell of food cooking. An individual with heart disease will be more sensitive to chest pains. A child who learns better through the auditory channel will orient better to a song about body parts than a picture of a body.

Attention holding: Attention holding is the maintenance of attention when a stimulus is intricate or novel. It is reflected by how long we engage in cognitive activity involving the stimulus. The infant who is engaged in attention holding will inspect the object visually and manipulate it with his fingers. In an older child attention holding may be maintained via internal thought processes, such as inventing rules to a new game or through attempts to extract principles from observing complex behavior. Novelty and complexity are the most potent mediators of attention holding. Objects or events that are both novel and complex for a young infant may involve interesting patterns, bright colors, unique spatial orientations, surprised looking faces, and meaningful events, such as feeding time. If an object, activity, or event is not complex and the demand to process information is low, the duration of attention holding will be very short.

When tasks are moderately complex, the individual will expend effort for learning. However, motivation plays an important role in determining whether a stimulus array can maintain attention. There are individuals with low levels of motivation who will expend little effort to attend regardless of the level of task complexity. These are individuals who present a great challenge to teachers and therapists who must identify these children from other children with short attention spans. The difficult task is to identify whether the problems of attention are related to either low motivation, sensory processing problems, cognitive impairments, or other processing problems (e.g., auditory, visual). Moreover, motivational problems may evolve if the child has more basic sensory or cognitive problems.

Attention releasing: The final stage in the attentional process is a releasing or turning off of attention from the stimulus. An infant will turn away from the stimulus; an adult may put the materials away or simply walk away and engage in a new activity. Interestingly, young infants may turn away from a stimulus in a highly stereotypic and consistent manner (e.g., look down to left when finished looking) (

Cohen, 1976).

The concept of releasing attention has functional implications. It helps us to reach closure on a given activity or event to be able to shift attention to something new. We turn our attention off when we fatigue physically or mentally of the activity, or when our arousal level has decreased and a different type of sensory stimulation is needed to maintain our alert and active state. Teachers use attention releasing with children by eliciting from the child when he is “all done” or “finished” before moving onto the next activity. Alternatively, attention releasing may function to lower our arousal when we are in stressing social interactions. For example, in the midst of a social confrontation, we may gaze avert to reduce our arousal level and lower the intensity our behavior (

Table 8.1).

Table 8.1

Sustained attention

| Phases of attention |

Response |

Stimulus |

| Attention getting |

Response to qualitative nature of stimulus |

Elicited by novel and salient objects or events |

| Attention holding |

Maintenance of attention |

Elicited by novel, meaningful, or complex objects or events |

| Attention releasing |

Turning away from stimulus |

Elicited by memory match or habituation |

In everyday situations, children are required to attend appropriately to objects, events, and tasks. Sustained attention during purposeful activity, such as manipulation of objects and free play, is important for the development of learning and performance. The way that we attend during different cognitive tasks, however, will depend upon the nature of the task. For example, different behaviors will be observed in an infant during manipulation, search, and cause–effect tasks. The infant attends to the characteristics that are most important to learn about the task. An infant may manipulate the object with his fingers to learn about an object’s texture, but will engage in looking behaviors during a cause–effect event.

There are developmental changes in the types of behaviors that we engage in as we learn more about the world. As a 4-year-old is able to engage in construction and problem solving skills, he exhibits less inattention (e.g., moving away from toys) than a toddler who may be focusing on mapping out his environment and asserting his independence. Focused attention during free play appears to be related to the child’s ability to respond to increased variety and complexity in tasks, the capacity to organize goal-directed activity, and the ability to inhibit extraneous motor activity (

Ruff & Lawson, 1990).

6. The role of effort in attentional tasks

What helps an individual to be able to put effort into a task? There are several things that seem to contribute to this ability. One is the individual’s mental resources or mental structures that help the person to process information. We know that there is a fixed supply of mental resources available to us. We have a limited capacity to process information and have all experienced the feeling of mental overload. The allocation of resources is influenced by factors, such as processing load imposed by the task (e.g., number of choices or decisions), criteria for successful performance, and level of arousal. More difficult processing tasks require the greatest mental load. When two tasks are performed concurrently, interference can arise that compromises performance even if the two tasks involve different processing structures. Most adults have experienced the problem of attempting to maintain a telephone conversation while someone is yelling, “Who is it? What do they want?”

Broadbent (1958) has suggested that we have a mental filter that determines which stimuli will be recognized and ultimately perceived by the individual. This helps us to conserve our mental resources.

Another factor that helps an individual to sustain effort is automization of learned skills. Once a skill is learned and becomes automatic, our attention may be directed toward more complex activity. For instance, once a musician has learned the notes of a musical composition, he can then concentrate on musical expression rather than focusing effort on reading the notes. Or, once a child has learned a skill, such as running, he need not concentrate on running, but can engage in complex games which require carrying (e.g., football) or kicking (soccer) objects while running. Attention is then drawn toward these other, more complex skills.

7. Selective attention: screening and selection

What allows a person to sustain and hold attention during a particular task and to screen out irrelevant information? This is the process of selective attention. Selective attention typically refers to the ability to select or focus on one type of information to the exclusion of others. It has both voluntary and involuntary components.

Active selective attention involves effort in sustaining attention toward a selected content and is based upon prior learning, experience, or training. Vigilant behavior is a type of selective attention when we focus on rare, near threshold signals. Passive selective attention is effortless and involuntary. Events that seem to be ignored are registered and perceived. This type of attention is important for protection against dangers.

The focus of selective attention may be sensory inputs or cognitive events. Examples of attention to sensory inputs include awareness of hair on your neck after a haircut or the feel of a friendly dog sitting on your lap. Selective attention directed toward a cognitive event is ideational and involves attending to a stimulus that may normally be ignored. For example, the individual may remind himself to do a particular task (i.e., taking out garbage, mail a letter) by setting up a cognitive flag associating the tasks with some other experience.

There appear to be three main things that assist a person in selective attention. (1) Neural mechanisms including suppression and inhibition of competing stimuli help the person encode new information and attend. (2) Attention is selective depending upon the cognitive schema available to the individual. (3) Structure in the environment may foster our ability to selectively attend.

8. Motivation, persistence, and self-control

Motivation and persistence contribute to the maintenance of attention. Persistence reflects both the capacity to sustain effort and motivation to attend to the task or event. Persistence is dependent upon self-initiated regulation of behavior. Self-regulation is the ability to comply with a request, and to initiate and cease activities in relation to task and situational demands. It is the modulation of intensity, frequency, and duration of verbal, motor, and social behaviors. Developmentally there is a shift from external points of control (i.e., another person structuring the activity) to internal regulation (i.e., self-directed planned activity). This process involves maturation, experience, and internalization of information about the social and nonsocial environment.

Kopp (1982,

2009,

2011) describes the development of self-regulation. The first phase, from birth to 3 months, is characterized by neurophysiological maturation. Arousal states are regulated and reflexive movement is organized into functional behaviors. During this phase, the infant learns to selectively screen information from the environment, particularly when overloaded with stimuli. Caregiver interactions and routines facilitate the infant’s state control, the ability to focus on salient features in the environment, and the capacity to attend to an increasing number of relevant inputs.

The second phase, from 3 months to 1 year, is characterized by skills in sensorimotor modulation. Voluntary motor control develops for nonreflexive acts. The infant learns to modify actions in relation to events and object characteristics, although, the infant does not yet have prior cognitive intent or a cognitive awareness of situational meaning. Motivation becomes an important determinant of behavior, although one sees caregiver responsivity as continuing to be important in eliciting and sustaining attention in the less active infant. This phase is important for organizing the social and nonsocial environment and in developing an awareness of actions and their results.

The third phase, from 9 to 18 months, is characterized by the infant learning to initiate, maintain, or cease physical acts. There is an increased awareness of social or task demands as defined by the caregiver. In this phase there is an emergence of problem solving, intention, or awareness that actions lead to a goal, and more adaptive behaviors. There are considerable quantitative and qualitative changes in cognitive skills with emergence of object permanence, simple use of tools in means-ends tasks, and early categorization. Cognition remains highly dependent on actions, but there is a growing awareness of the self as a separate identity. The child is dependent on signals from the environment and does not yet have the capacity to recall events or to reflect on one’s own actions.

The fourth phase begins at approximately 2 years of age. This phase is characterized by the emergence of self-control and the progression to self-regulation. Self-control is the ability to delay one’s own actions and to comply with caregiver and social expectations in the absence of external controls. Self-regulation is the capacity to reflect on one’s own actions and generate strategies in response to changing situational demands. The development of representational thought and recall memory are major hallmarks of this phase, allowing for knowledge of social rules and situational demands. Memory is limited in the 2-year-old and is best when meaningful, semantic cues are present and brought to the child’s attention. Compliance is still determined by the child’s level of pleasure rather than reasoned logic or need, and the child remains stimulus bound when required to wait. Caregivers continue to be important mediators in self-control at this age.

The development of persistence in attentional tasks is related to impulse control and self-regulation (e.g., ability to delay touching an attractive toy) (

Kopp, Krakow, & Vaughn, 1983). Interestingly, it is not related to compliance. The stubborn, strong-willed child who wants to do it their own way has persistence in what they want to do. Language competence also helps the child develop self-control. When the child uses verbal mediation, describing his actions as he enacts them, it helps not only to organize the behaviors but to regulation actions.

Kopp’s theory of self-regulation is unique as a model of attention because it accounts for the interaction between individual and environment over development and considers the importance of motivation, impulse control, and capacity in attention. The basic process underlying self-regulation is described as the child’s ability to initiate, maintain, and cease activity. This process seems to parallel Cohen’s attention getting, attention holding, and attention-releasing stages. Kopp integrates many of the components of attention into her developmental model. In the first phase of self-regulation, Kopp describes the infant as developing selective attention and the capacity to attend to inputs in the environment. Unlike other models of attention, Kopp stresses the role of the caregiver in facilitating the young infant’s attention to salient stimuli and to increasing numbers of relevant inputs. Over the course of development, the infant’s attentional capacity shifts from external to internal control. This is a departure from the view of attentional capacity as solely a function of information processing and mental effort. Kopp describes self-regulation as the ability to modify actions in relation to situational and task demands. The organization of the social and nonsocial world together with an awareness of one’s own actions and their results are considered the basis for generating strategies for self-initiated behavior.

Components of this model have been integrated into the model of executive functions that

Barkley (1997,

2013) proposes. In his model, it is the interaction of these

functions that permits normal self-regulation. At its most basic level is behavioral inhibition, which is the foundation for the other executive functions. Behavioral inhibition has three functions: (1) to prevent a prepotent response from occurring, such as the child’s impulse to touch a toy before it is his turn; (2) to interrupt an ongoing response that is not ineffective or adaptive, such as a child knocking over a tower of blocks before he has completed the tower; and (3) to delay responding and to prevent internal thoughts or external distractions from interfering with emitting an appropriate response. In the next level, there are four functions that contribute to self-directed behavior. These are listed below with some examples of how these functions are manifested in the child.

A. Nonverbal working memory

– memory of events and everyday sequences,

– imitation of behavioral sequences,

– anticipation of events and preparation to act,

– self-awareness of own behaviors (past, present, and future),

– concept of time.

B. Internalization of speech

– internal narrative describing external events, actions, and sequences,

– verbal reflection of actions and ideas,

– self-questioning and problem solving,

– internalization of structure and rules from others,

– generating rules related to consequences of behaviors.

C. Self-regulation of affect, motivation, and arousal

– self-regulation of affect (e.g., inhibiting or delaying affective or behavioral responses),

– reading social cues accurately and social perspective taking,

– modulating arousal states for goal-directed actions,

– self-regulation of drive and motivation to respond.

D. Reconstitution

– analysis and synthesis of behavior (e.g., breaking behavior into sequence or component parts),

– creating a diverse range of verbal responses during social interactions,

– generating a range of adaptive motor responses in response to newly learned situations or behavioral challenges,

– generating a range of goal-directed behaviors,

– evaluating behaviors and their consequences and modifying actions (if–then).

These four functions contribute to the child’s developing the following capacities:

• to inhibit irrelevant responses,

• to form goal-directed behaviors,

• to persist during activities,

• to respond to external feedback and to modify responses accordingly,

• to execute new or complex motor plans or sequences,

• to respond flexibly in relation to task or situational demands,

• to self-control one’s own actions via internal or external information.

The models proposed by Kopp and Barkley are useful in understanding how self-control, persistence, and motivation develop in the young child and provide the clinician with a template for generating a developmentally based treatment approach.

8.1. Neurobiological basis for focused attention and executive control

The prefrontal cortex plays a very important role in guiding and directing focused behavior. It is the executive functioning engine of the brain and is important in supervising time management, decision making, impulse control, planning and organization of behavior, and critical thinking. The prefrontal cortex mediates our ability to think, manage time, and communicate with others. It is critical for forming goals, planning ahead, plan execution, and to adapt and modify the plan as obstacles or mistakes occur. The prefrontal cortex is the part of the brain that allows us the capacity for theory of mind, for example, the ability to think about our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors before we act and the ability to take another person’s perspective and reflect upon what they would think about our responses. The prefrontal cortex, especially the dorsolateral portion, is involved in sustaining attention and filtering less important thoughts and sensations. It helps us to remain on-task, persist, and quiet extraneous distractions from other brain areas (e.g., the limbic system and sensory portions of the brain). Through its inhibitory connections with the limbic system, the prefrontal cortex helps us to integrate our thoughts and feelings and to think before we act.

Persons with poor prefrontal cortex functioning are apt to have poor impulse control, have difficulty learning from their own mistakes, and have poor problem-solving, planning, and organizational skills. Deficits in the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex are apt to result in a person having high distractibility, a short attention span, apathy, and decreased verbal expression. Other problems include hyperactivity, procrastination, disorganization, short-term memory problems, and poor judgment. The person may also misperceive situations and have trouble learning from their own experiences. Deficits in the inferior orbital cortex can contribute to poor impulse control and mood control problems due to the connections with the limbic system.

9. Treatment applications

In this next section, a variety of suggestions are offered to improve arousal and alerting for focused attention and to develop better self-control, sustained attention, and self-monitoring (see Skill Sheets #4: Improving attention span and #19: Installing structure and organization). Treatment approaches integrate principles from sensory integration and cognitive-behavioral treatment models.

9.1. Techniques to improve arousal and alerting for focused attention

9.1.1. Environmental modifications

Objects for school and home should be organized in clearly defined bins or shelving, sorting objects by category or by the type of task (i.e., upcoming projects, “to do” tasks). File folders or boxes should be labeled clearly in logical categories and stored in places where the child can easily retrieve their location. Due to memory retrieval problems, some children need a centrally located list to help them use their organizational system.

The number of objects available at any one time should be limited, clearing work space or counter tops to avoid overstimulation. This usually requires that the child practice putting things away as soon as they are finished with them rather than leaving objects scattered about. It is also helpful if the child can declutter their bedroom and study area to help their ability to stay focused. Most children need to declutter every few months to keep things organized. It is a good idea to put toys away in storage, recycling them every few weeks to help maintain novelty.

Whenever possible, the child should seek seating alongside a wall or by a corner of the room at home and in the classroom when working or trying to hold a conversation. Sitting in a booth in a busy restaurant by the wall, preferably a corner location will help the child listen and converse. The use of enclosed spaces, such as a pup tent filled with soft pillows or a refrigerator box lined with soft carpet is often helpful.

A portable fold-up cardboard “cubicle” can be constructed and placed on the child’s desk at home or school to limit visual distractions. The child should avoid trying to do concentrated work in large, wide-open spaces unless these are fairly bare rooms with windows that look out at nature.

If the child is very restless, it might help to sit on a soft inflatable cushion or to put a weighted blanket or large weighted gel pad on their lap to quiet the body. Sitting in a beanbag chair is often helpful for reading activities.

It is also very helpful to seat the child next to a quiet, organized child who can model focused attention.

9.1.2. Recreational activities

The child should seek sports that provide high contact and/or resistance to organize the body. Some ideas might be karate, horseback riding, wrestling, swimming, and working out with weights or other high contact sports.

Movement is very organizing and helps to inhibit hyperactivity. The child may rock in a glider chair or rocking chair, swing on an outdoor swing, or workout on equipment that offers movement, such as an elliptical machine.

The child should avoid high intensity movement activities after dinner, instead engaging in slow rhythmic movement, such as rocking in a chair or doing yoga or tai chi to help quiet their hyperactivity.

9.1.3. Auditory inputs

Many persons are soothed by Gregorian chants, Mozart, and music with female vocalists as background music.

Some children respond well to New Age music or relaxing music tapes with environmental sounds on them (waterfalls, bird sounds). The Hemi-Sync music tapes are especially useful. These CDs provide an integration of music with environmental sounds, programmed in such a way to help focus attention.

Some children need to wear noise cancelling earphones or earplugs to muffle noise.

Carpeting on all or part of the room may help to minimize extraneous noise.

9.1.4. Visual inputs

The child may highlight important visual information by underlining key points in yellow marker, using bright post-it notes, or placing a physical boundary around content that the child wants to focus on (i.e., exposing only the recipe on the cookbook page to avoid scanning the whole page each time).

Objects should be kept in organized locations, establishing routines around their usage (i.e, electronics and backpack always placed in same place as soon as the child comes home).

Important events and tasks to do should be posted in a central location, preferably a calendar with last minute reminders posted on a dry erase board.

The child should practice breaking projects into realistic time lines, perhaps setting up a system on their computer that flags reminders either daily or weekly.

9.1.5. Arousal versus calming activities

Find out what time of day is the child’s best alert period (most people are morning or evening persons). The child should try to do things of quiet concentration during those times.

Some children need to move around frequently at home or school. Movement breaks should be purposeful, such as carrying a heavy box down to another teacher’s room, moving furniture between activities, or wiping chalkboards clean. Most individuals need to move every 25–30 minutes to maintain an optimal level of attention.

Many persons with ADHD need to do activities that organize their body. The child may talk on the phone while squeezing a stress ball, therapy putty, or handgrip strengthener. Some children do well burying their hands or feet in a bin of dried beans while concentrating on a task.

Eating a small snack of crunchy hard foods can be very organizing (hard pretzels, rice cakes, ice chips, carrot sticks, apples)

Before bedtime the child should do a relaxing calming routine, such as warm bath, back massage, and pressure to the palms, especially the web space of thumb, and a foot massage.

It is very calming to engage in linear, forward–back rocking while doing a visual focusing activity (reading, looking at photos or art) or while listening to rhythmic soft music.

Some children like to lie under a heavy quilt or wrap themselves in a soft afghan.

Every person should have a place that they associate as a calm-down space. Ideally it is in a cozy, dimly lit place, such as a comfortable reading room with a reclining chair, soft pillows, and perhaps a water fountain and lit candles or dimmed lighting.

It is very helpful for the child to identify when they are feeling hyper and wound up versus calmer states of being. If the child is feeling very hyper, that is not the time to engage in focused tasks and instead they should do a movement activity, such as walking the dog, exercise, or yoga. Often the child feels pressure to get things done and winds up even more, then derails their performance by not being in an optimal state to attend to detail or they rush through the task and make mistakes. Learning to “let go” of the task in the moment to self-calm, then return to it when they are in a more optimal state of attention and arousal is more productive than becoming frantic and hurried. Children often respond well to learning how to label calm and focused states (i.e., “your engine is running at the right speed to concentrate” vs. “your engine is on top speed and needs to go slower”).

9.2. Things to do to help develop motivation, self-control, and sustained attention