I can’t stand our child’s crying another minute! This has been going on since he was born. He’s the baby from hell! My husband told me that if I didn’t fix his crying, he was leaving home. We can’t find any babysitters to take care of him because he is so irritable. I worry that someone else might abuse him because they wouldn’t love him like I do. I’m exhausted and at my wit’s end!

These words, spoken by a parent with an irritable child, are depictive of the tremendous impact that an irritable child can have on the parent–child relationship and family life. Parents become frantic in their attempts to console their child. When nothing works, parents often feel ineffective. They may worry why their child appears unhappy most of the time. For the child, it is an unsettling experience to be chronically unregulated when things like transitions in activities and small frustrations set them off. They learn to depend on their parents to soothe them because they lack strategies for self-calming. And because they are irritable most of the time, they may not experience pleasurable interactions with others.

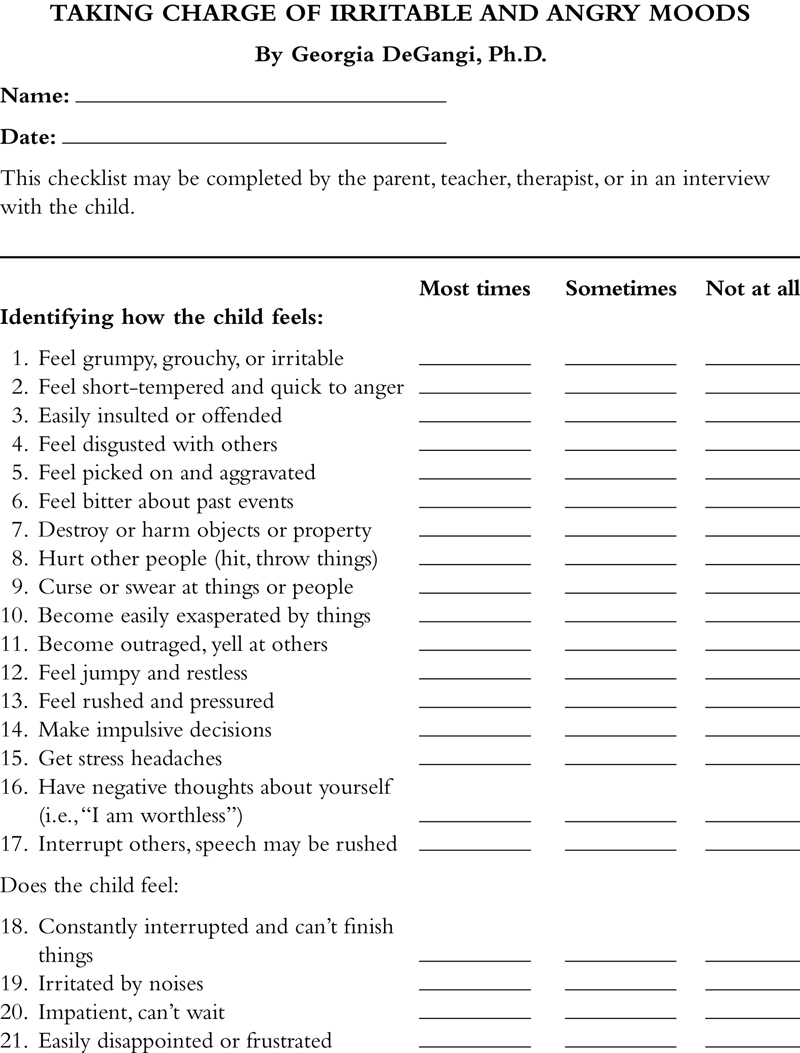

There are many reasons why a child is irritable or has mood regulation problems. To be most effective in treating these problems, it is important to understand the way in which emotion regulation develops in the young child. This chapter begins with an overview of different views of emotion to provide a framework for treating irritability and other disorders of mood regulation. Since a major aspect of mood regulation relates to how emotions are socialized, a developmental–structuralist framework is presented. Suggestions for treatment of different problems related to mood regulation and irritability are described along with several case examples of children at various ages. Lastly, a detailed checklist is provided that can help identify sources of irritability and target areas for treatment.

1. What is an emotion?

Emotions have a powerful impact on our experience of the world around us. Emotional expression provides a window into an individual’s internal experience of the world. They motivate our actions and affect the way in which we interact with others and our environment. Emotions provide life experiences with meaning. By guiding our thoughts and actions, emotions have a regulatory function, thus helping us to acquire adaptive behavior patterns and to motivate interactions with others (

Dodge & Garber, 1991). Through the expression of emotion, we can learn about how a person perceives him or herself and others, and how well they self-regulate when presented with challenging situations.

There are many individual differences in how people experience and express emotions and interact with others. Many people are predominantly happy, content, and curious. Others may be often withdrawn, sad, and depressed. Still others appear angry, destructive, and disorganized. Most people display different emotions and act differently depending upon the situation and their underlying mood at the time. But when a person is predominantly withdrawn, avoids other people, and has no interest in learning most of the time, it can affect their development and adaptability. Likewise, the child with a mood disorder who is angry, destructive, and overly aggressive will have difficulty engaging in appropriate interactions with others and in modulating their activity in everyday life.

Over the years, there has been considerable debate about what constitutes an emotion. Is it a subjective feeling state, such as feeling “depressed,” “content,” or “anxious?” Is it what motivates our interest in the world and guides our social interactions? Is emotion the outward motor expression of feelings—the smile, the scowl, the loud, stern voice, or the uplifted buoyant body posture? How much of emotion is affected by cognitive appraisal of a situation, event, or stimulus and how much by physical or autonomic responses (i.e., heart racing, cold clammy hands) that are experienced during anger, pleasure, or other emotional states? Most current views of emotion embrace all of these components. A broader view is generally accepted by emotion theorists who consider emotion to be the interface between the individual and his environment. Emotions mediate the individual’s capacity to adapt or respond to a variety of experiences. There are five major areas related to emotional regulation. These include:

1. Cognitive appraisal: Before, during, and after an emotion is experienced, the individual engages in cognitive appraisal. This process of evaluating the situation on a cognitive level determines what emotions are elicited. Some of the things that impact cognitive appraisal include:

a. Reading and understanding social cues: The irritable child may not be able to read and understand social situations and evaluate whether they should approach or withdraw. They may react in an unpredictable manner because of this difficulty.

b. Perception including face recognition and discrimination of affects: Some children have difficulty reading facial and gestural signals. As a result, they may misconstrue what a person is trying to convey. Often it is difficult for them to understand when firm limits are placed on them because of this problem.

c. Predicting one’s own behavior and that of others: A major goal for the child with mood regulation problems is to begin to predict their own behavior and modify it in response to different situational demands. Learning that certain behaviors have consequences is important to this process.

2. Physiological aspects of emotions: One of the things that help us to link meaning to emotions are physiological responses. As cognitive appraisal takes place, physiological responses activate arousal to allow the person to respond accordingly. This is important to prepare the person for action. For example, in dangerous situations, the person needs to be ready to flee. Without a physiological readiness, the person may not survive. Both neuroendocrine and autonomic states contribute to the physiological activation of emotions. Many irritable children are always in a state of hyperarousal and, therefore, do not have the typical physiological responses one needs to react in a calm and focused manner.

3. Expression of emotion: Communication of reactions, feelings, or intentions to others during social interactions is an important component of emotion. The motor expression of emotion is manifested through the neuromuscular system and consists of facial patterning, postures, and gestures. Often the irritable child expresses intense negative emotions (e.g., anger, distress, frustration). They have difficulty communicating more subtle ranges of emotions (e.g., express through words or facial expressions that they are beginning to feel frustrated vs. tantruming) and they may have little opportunity to express more positive emotions.

4. Socialization of emotions: As children develop, they are reinforced to express certain emotional displays. This process occurs first through the parent–child relationship, but if this relationship is affected by the child’s irritability and mood regulation problems, it is more difficult for the parent to provide positive social feedback. As the child grows older, they may have relationships that are negatively reinforcing. For example, others are likely to avoid them because of their bad temper, or they may have a history of bullying, being kicked out of play groups or school programs, and have few satisfying or rewarding relationships.

5. Modulation of emotion and mood states: Learning how to modulate emotions in response to internal states, situational demands, and the social context is a very important skill. How an individual perceives the experience of the emotion during and after its expression relates to the subjective feelings associated with emotions. Cognitive factors, such as memory and imagination play an important role in defining the subjective experience of emotions.

These components of emotion do not necessarily occur in this sequence; however, there is general agreement that the concept of emotion should include these five elements (

Scherer, 1984). Understanding the various elements of emotion regulation is important for treatment planning in working with children with regulatory disorders. In the next section, details about the different components of emotion regulation will be discussed with emphasis on how problems in each area may be observed and treated.

2. Cognitive appraisal

2.1. Reading of social cues

When faced with a situation, an individual makes a cognitive appraisal which affects the intensity and quality of the emotional reaction. The individual relies upon already acquired knowledge about similar situations, memories of past experiences, perceptual skills in reading signals or cues from the environment, as well as analytical skills in appraising the situation. This appraisal process is ongoing and may be manifested in a number of different emotional responses over time as the individual reflects upon past and current experiences. For instance, suppose the child thinks that a situation is very demanding. At first, the child may experience much apprehension and fear. If the child remembers that he was successful in a similar difficult situation in the past, he may feel challenged and excited after his initial response. However, if he experienced extreme frustration and feelings of incompetence in the past, he may seek to avoid another such experience and exhibit negative emotions. This is very common with performance anxiety.

How cognitive appraisal might impact a child with mood regulation problems is depicted by Owen, a 4-year-old child who was struggling at preschool. He often became irritable when there were transitions in activities, his space was invaded by other children, activities were more rambunctious, or when the classroom noise level became loud. He felt that he wasn’t ready to move on to the next activity when the children were expected to do so. Although he was a very competent child, he had trouble adjusting to change and would become distressed when expected to do certain tasks, such as share toys with other children or clean up his toys to get ready for snack. Usually after about 2 hours at school, Owen would begin to show his distress by hitting or biting other children or by withdrawing. His responses were very unpredictable with some good days, then followed by several days with multiple incidents. Each time he bit a child, he was sent home from school. Within a month, he was being sent home so frequently that his parents chose to keep him at home to give him a break from the stress of school. As we tried to work out a viable solution to the problem (e.g., getting a full-time aide to help him make transitions, to stop him before he bit another child, and to organize him when he appeared distressed), Owen began to make comments that he never wanted to go back to school again. In the next month that it took to find an aide, we saw Owen regress. With each day that he stayed home from school, he became increasingly more agitated, refusing to change his clothes, wanting to isolate himself in his bedroom, and screaming at his parents whenever they made the simplest of requests. As we reintroduced Owen back into school, we had to change his cognitive appraisal of school and himself to a more positive one. We were able to accomplish this by beginning with a short school day and a shortened week of school at first and using positive reinforcement from his aide for accomplishing tasks. We provided scheduled breaks during the day when he could reorganize himself (e.g., calming by sitting in a bean bag chair and looking at books, sucking on ice pops, or building a fort that he could go inside). We instituted a school and home program that reinforced good behavior and compliance, for playing friendly (e.g., not biting other children), making transitions (e.g., clean up toys when time for snack), and self-calming when agitated (e.g., asking for time alone in bean bag chair). Within a few months he became much more compliant both at home and school and was beginning to make more positive self-statements (e.g., “I want to go to school”; “I like doing this” instead of “I’m a bad boy,” “I’m angry”) and playing more with other children in a prosocial way.

2.2. Perceptual of facial expressions

Before a person can engage in cognitive appraisal, they need to be able to perceive signals and cues from the environment. One of the first ways that we learn to discriminate emotions is through understanding the meaning of various facial expressions. There are several important components that comprise this skill. These include:

1. Perceptual understanding of the face and its structural components: Discrimination of the face-hair outline develops as early as 4–7 weeks of age. By 5 months, infants become interested in the mouth and have a concept of “faceness” (features of the inner face as distinctive from the head shape). And by 7 months, the infant can detect different poses or angles of the face.

2. Recognition of affective expressions: The reading and understanding of different facial expressions (i.e., smiling or frowning faces) relies upon the integration of auditory and visual perceptual skills over time and space. It is the stopping and starting of facial movements that helps the infant to discriminate changes in facial expression. Between the ages of 3 and 7 months, the infant gradually acquires the ability to differentiate an increasing number of expression changes. For example, the 3-month-old can distinguish smiling, angry, or frowning faces. By 5.5 months, the infant can distinguish surprised faces and the 7-month-old can distinguish happy from fearful faces.

3. Simultaneous perception of vocal expressions, speech content, gestures, and body posture changes: This skill requires perceptual mapping of visual and auditory cues and their related meanings. The neonate is already attuned to characteristics of the human voice and can distinguish between the mother’s and a stranger’s voice. By 3–4 months, the infant can detect synchrony of voice with a moving face. Five to 7 month olds are able to distinguish when facial and vocal expressions match. A developmental task for all persons is to learn how to process both visual and auditory cues and their synchronization in reading facial signals. Children with autism spectrum disorder or nonverbal learning disability frequently struggle with this developmental task.

Sasha was a 10-year-old child with nonverbal learning disability who often misconstrued facial expressions in others and consequently attributed emotion to them that was inaccurate. In a group play situation, children were playing out a pretend play scenario where they built a fort to prevent the mean troll from scaring them. No matter how much facilitation she received from the therapist, Sasha would not join in the play with the other girls, and instead assumed the role of an angry monster who stomped around the room and roared. After the group was over, Sasha said, “The other girls were mean to me. They wouldn’t let me play with them.” Obviously Sasha had a completely different view of what happened in this play scenario and somehow projected her feelings into her role as the angry monster.

4. Understanding the meaning of facial expressions during interactions: This involves skills, such as differentiating a genuine smile from a forced smile or identifying different types of cries in a crying baby. Understanding facial expressions and their meanings begins through instinctual imitation when the infant reads and practices facial signals during interactions, such as mouth opening or tongue protrusion. By 6 months, the baby is responsive to the facial expressions of their mother. For example, if their mother looks sad, the baby will show more sadness, anger, and gaze aversion (

Termine & Izard, 1988).

Some children with mood regulation problems have difficulty in the perception of facial expression and in reading and understanding affective expression. They seem to become overwhelmed by emotional expression and may turn away to avoid eye contact or they may misconstrue the meaning of different facial expressions. One example of how this plays out is when parents report that no matter how clear their signals are when setting limits, their child does not listen or the child reacts by laughing at them. Suppose you present a picture of two children teasing another child to a 6-year-old child who has problems reading social cues. The child may misread the picture and say that it is a picture of three children playing ring around the rosey. There are also some children who have perceptual problems in recognizing different people’s faces and may react as if they have never seen the person before. Some children may be overwhelmed by anxiety or overstimulated by sensory input to the point that they cannot process verbalizations while also reading facial and gestural cues.

For example, 11-year-old Walter appeared very stiff and uncertain when interacting with others. He was frequently so anxious that he claimed that he couldn’t hear what others said to him, as if his ears were plugged up with fuzz. In fact, the middle ear muscles do constrict when a person is anxious causing this phenomenon. Not only that, but Walter would be so overwhelmed by crossing the street in front of my office building as he walked from his mother’s car, that he usually began his therapy session asking me to be very quiet and calm for at least the first 10 minutes to help him transition into “interactive” mode. I was aware that I had to keep my facial expressions as unanimated as possible and even to speak with less inflection. We practiced different styles of interacting (i.e., slower paced, benign topics to more animated, emotionally evocative topics) in addition to talking about his understanding of my facial and gestural cues and his internal state of overload.

In working with children with mood regulation problems, it is important to determine if the child is struggling with the perceptual aspects of facial expression and/or reading and interpreting social or affective cues. It is important to observe how much the child can process and to provide the right amount of stimulation that allows them to take it in without becoming overwhelmed. For example, Nina, a 6-year-old child with problems reading facial cues, enjoyed playing dress-ups. She particularly liked playing “Super-Girl,” putting on a gold cape and silver leggings. Nina liked to play out disasters, such as having cookies burning in the kitchen, little animals stuck in crevices, or babies getting lost in the woods. It seemed that she liked seeing the therapist express exaggerated expressions of alarm or surprise. She would play Super-Girl who would come to the rescue of the therapist in the burning block house. At first Nina needed the therapist to do the same script each time so that she could predict and understand what affective expressions went with which scenarios, but after a while, Nina liked it when the therapist made other things happen that might be silly or novel (i.e., a stuffed animal purposely sets the fire just so he could ride down Super-Girl’s fireman ladder). It was important to move from more expressive emotions to more subtle ones and from predictable events to ones that were less predictable. The dress-ups and fantasy play were ideal ways of helping Nina to learn how to read social cues.

5. Neural mechanisms underlying perception of facial expressions: The processing of emotional expression involves complex pattern recognition and coordination of visual (e.g., facial expressions) and auditory inputs (e.g., voice intonations). Studies of patients with hemispheric dysfunction have shed light upon the role of the right and left hemispheres in the perception and comprehension of visual and auditory stimuli related to emotional expression.

Generally, the right hemisphere is dominant in the recognition of visuospatial and auditory patterns and is important in integrating holistic perceptual properties. Some of the specific functions of the right hemisphere include the following:

a. Mediation of attention and emotional behavior,

b. Face recognition,

c. Discrimination of emotional expressions,

d. Comprehension and expression of affectively intoned speech,

e. Judging the quality of an emotion (e.g., positive or negative),

f. Recall of facial expressions from a model or picture,

g. Inhibition of inappropriate positive affects (pathological laughing).

The left hemisphere also plays an important role in cognitive appraisal of emotion. The left hemisphere is important for the following functions:

a. Verbal mediation and verbal labeling of emotional faces,

b. Motor planning of facial expressions (i.e., smile, show gums),

c. Inhibition of negative affective expression (pathological crying),

d. Comprehension and memory of emotionally charged stories.

There are some functions, however, that are attributed to both hemispheres. These include the following:

a. Perception of humorous content of pictures,

b. Naming and selecting emotional faces, although this tends to be a right hemisphere function more than left.

Understanding what neural mechanisms might be compromised for a child is useful in treatment planning. For example, some children with significant language impairments struggle with labeling emotions and may repeatedly ask questions, such as “Are you happy?” when they see your smiling face. In contrast, children with nonverbal learning disabilities may need concrete verbal labels to help them interpret social interchanges (i.e., “watch for when Michael looks away from you and stops playing with the ball, then ask him if he wants to do something else with you”).

Jeanie was an 11-year-old child who often smiled or laughed when talking about a distressing event (i.e., being bullied at school for using a rolling backpack). She seemed unaware that her facial expression was a mismatch with her verbal content. Interestingly, as she became more aware of this behavior, she became more in touch with the depth of her feelings. It was only then that she could process how angry she was by the bullying events at school. Sometimes she would crush bubble wrap in her sessions with me as she talked about these events, thus giving her a physical outlet for her anger and helping her body to process the anger she felt inside. We used a variety of techniques to help her gain more of a match between her internal mood state and her outward expression of emotion. It was useful to link verbal interpretations of visual feedback by videotaping her and watching the tape together to discuss what she was feeling in the moment. She also learned to check her expression in the mirror to see how she presented herself to others and to see if there was a match between her face and her internal emotions.

2.3. Predicting one’s own behavior and that of others

Social situations provide many cues that assist the individual in integrating perceptual and cognitive meanings. When a situation is highly novel or the person lacks experience or skill in interpreting meanings, the individual tends to rely heavily upon feedback from other people, particularly those who are important to them (i.e., peers, parents), as well as cues about a situation. A classic example is that of the 9-month-old infant who is crawling on a clear plastic platform that presents the illusion of a visual cliff. The child at this age does not have the perceptual understanding that he might fall off a cliff, therefore, he relies upon his mother’s expression. Whether his mother smiles and encourages him to crawl or expresses fear will affect his appraisal of the situation as one that is safe or dangerous.

The young child is more dependent upon facial cues of individuals experiencing the event, but as children grow older through the school-aged years, they rely more on situational cues. As children mature, they are also better able to integrate both facial and situational cues (

Hoffner & Badzinski, 1989). We see this in many everyday situations with adults as well. Suppose you are invited to attend a social gathering of persons from a highly different socioeconomic and cultural background. Most individuals would watch others who are comfortable with the situation to determine what behaviors are expected. Men and women may talk together in segregated groups. It may be expected that jokes will be received with modest chuckling versus loud laughing. The hostess may be offended if the guests do not eat second and third helpings of food.

3. Physiological aspects of emotion

Descriptions of emotion often involve both physiological responses (e.g., peripheral autonomic nervous system) and facial expression. The physiological component of emotion may involve changes, such as increased sweating, throbbing or racing of the heart, pupillary dilation, facial flushing or blanching, and gastric motility. These autonomic responses (i.e., heart rate) often parallel facial expressions associated with emotion (

Darwin, 1872). Darwin suggested that there were specific neural pathways that provide communication between the brain and the periphery associated with emotions. When emotional states occur, heart rate changes occur which in turn influence brain activity.

3.1. Mediation of emotion via autonomic responses

There has been considerable debate about whether the emotion or the autonomic response occur first.

James (1884) described emotion in terms of afferent feedback from the viscera to the brain. Different emotions were caused by highly specific changes in

the autonomic nervous system. For example, an individual may experience heart racing and increased sweating in a stressful situation. These autonomic responses would help the person to label feelings of fear.

In contrast,

Cannon (1927) argued that autonomic changes occurred in response to brain processes which defined the experience of emotion. A person would first assess a situation as one evoking fear, then would experience the associated autonomic responses.

The question posed by these two theorists is an interesting one. How would a lack of afferent feedback influence the ability to experience emotions? Imagine the patient with an artificial heart who would not experience shifts in heart rate during different emotional experiences. Would this individual feel emotions in the same way as previously experienced before heart surgery?

3.2. The specificity of emotions

Although there seem to be differences in opinion about the role of afferent feedback in the experience of emotion, research shows that different emotions elicit distinct autonomic responses.

Ekman, Levenson, and Friesen (1983) have demonstrated a degree of specificity between autonomic activity and facial expressions. It appears that there are intimate links between the neural mechanisms controlling the facial muscles and the autonomic nervous system. When emotions occur, specific facial expressions and unique patterns of autonomic activity are elicited depending upon the emotional state. Ekman and his colleagues suggest, unlike the James theory, that peripheral feedback from the autonomic nervous system to the brain is not required in order to experience emotion.

But what happens when a person assumes a facial expression by simply contracting different facial muscles that are part of that particular expression? Do they experience the emotion as well? Here is an experiment for you to try. Raise your brows, hold them raised, and pull your brows together, now raise your upper eyelid and tighten the lower eyelid, and stretch your lips horizontally. What does your face look like? Your face should look as if you are experiencing fear. Did you feel any autonomic changes that were related to fear?

In an experiment where subjects assumed different facial expressions in the same way that you just did, the subjects experienced different autonomic changes, such as changes in skin temperature and heart rate (

Ekman et al., 1983). Of course, the autonomic changes are mild in contrast to when the emotion is actually experienced. These results may explain why some people who are feeling low can pick up their mood by “putting on a happy face.” The act of smiling may actually elevate the way we feel even if it starts out as deliberate rather than spontaneous.

3.3. Autonomic responses associated with discrete emotions

Fear and sadness result in cooler skin temperatures while angry faces result in increased skin temperatures. Heart rate generally increases with negative emotions (e.g., anger, fear, and sadness) but decreases with other emotions, some of which are positive (e.g., happiness, disgust, and surprise).

3.4. The Polyvagal Theory of Emotion

The link between autonomic nervous system activity and social communication is described in the Polyvagal Theory of Emotion (

Porges, 1995). In this theory, there are three phylogenetic stages of neural development. The first stage represents the primitive unmyelinated vegetative vagal system. It is characterized by immobilization responses. The vagal system functions in the capacity of helping the body digest food and to reduce cardiac output when the person is confronted with either a novel or threatening situation.

In the second stage, the spinal sympathetic nervous system is activated which serves in increasing metabolic output while inhibiting primitive vagal influences. This stage is one of mobilization and is represented in the person’s capacity to engage in “fight or flight” when confronted with threatening stimuli.

The third stage is characterized by the myelinated vagal system that helps to regulate cardiac output and to foster engagement and disengagement with the environment. It is brain stem mediated and it controls facial expression, sucking and swallowing, breathing, and vocalization. This system has an inhibitory effect on the sympathetic nervous system, effects on cardiac function, and promotes physiological calming.

Porges (1995) theorizes that this is the system that provides the neurological basis for early mother–infant interactions, as well as the development of complex social behaviors. Some of the social behaviors that this system impacts are emotional expression, vocal communication, and contingent social behaviors.

In treatment we frequently use deep breathing exercises to help calm states of agitation, anger, or other dysregulated mood states. The polyvagal theory helps to explain the neural mechanism behind why deep breathing helps calm the nervous system to allow for better social engagement and attachment to others.

3.5. Neural mechanisms underlying physiological changes

Afferent feedback from the facial and postural muscles plays an important role in modulation of emotion. When these afferents were severed in an experiment with cats (reticular formation left intact), the cats became mute and completely lacking in facial expressiveness and purposeful behavior. They also became hyperexploratory but lacking in intentionality (

Sprague, Chambers, & Stellar, 1961). It seems that afferent feedback mechanisms are important to self-monitor emotional expression and to organize purposeful exploration.

Developmental shifts are observed in neurophysiological control of facial expressivity. With maturation, the infant displays a greater range of expressivity but, at the same time, can self-regulate affect in response to situational demands, thereby showing a trend toward greater cortical control of facial expressions. There is also greater control of autonomic functions with age. As the individual matures, they are less likely to respond with high variability in autonomic responses (i.e., heart rate and respiration) as they learn to adapt to various novel or stressful situations. Therefore, in normal development, there is greater myelinization of the brain in conjunction with greater regulation of autonomic functions that parallels the affective expressivity and control.

Some individuals seem to have a great deal of difficulty in recognizing the autonomic responses that accompany emotions. As a result, they may not perceive that they are getting angry or upset until they suddenly blow up. This has important implications for parents who may be at risk for abusing their children. It is important to teach them how to recognize the bodily signals that mean they are getting angry (e.g., stiffening of muscles, skin getting hot, stomach churning, and so on) so that they can cool off before they explode at their child. By tuning into these body signals, the person can learn to control their behavior better.

The task of learning how to read body signals was a major piece of intervention with 9-year-old Alexis. She had a short fuse and would explode, screaming at her parents and throwing things whenever she experienced the slightest bit of frustration. Her tantrums would go on for several hours which resulted in the whole family being up to all hours of the night trying to console her. Her parents thought that Alexis looked like a wild animal with hair falling in her face, her body slumped over, and hands clawing at the air like a tiger. Alexis would also shut down when she became depressed, hiding under a table or sitting inside her closet for hours on end. These mood changes would come on suddenly and once in an intense mood state, Alexis had considerable difficulty coming out of them. Although she was a child who was helped by medications, through therapy Alexis began to be able to recognize when she could feel her mood shifting to anger, frustration, or sadness. When she felt herself becoming upset by things, she could focus on what her body was telling her, then take steps to soothe herself before her mood state progressed too far. Doing things like jumping on a trampoline, kicking a soccer ball, or playing piano helped her to self-calm. Alexis also talked with me about her “Tantrum Warning Device,” (a rainbow colored semicircle ranging from red for anger, orange for agitated, yellow for frustrated, green for calm, and blue for sad) a concept that we used to help her predict what situations caused her to become upset. For instance, doing homework almost always caused her warning meter to go up to a “medium sizzle.” Not getting to stay up late and play Nintendo would make her get “boiling mad.” The object of the warning device was to recognize when her mood was moving from mild to mild-medium or medium anger and get it back down again by calming herself.

4. Expression of emotion

The expression of emotion involves facial expressions, gestures, posture, movements, and vocal responses. This outward display of emotion, also called “affective expression,” is linked to our inner emotional experience. The expression of emotion is primarily facial. Since the facial musculature has greater sensory and motor innervation than postural muscles or visceral organs (i.e., heart), expression of emotion through the face is much more specific. Facial expressions provide information or meaning about the emotional experience of the sender to other persons. They also provide internal feedback to the person emitting the facial expression.

In order for an emotional signal to capture someone’s attention, it should involve as many dimensions as possible. The toddler who sees his parent frown, stomp his foot, point with his finger, and firmly state “NO!” knows that his parent means business. In contrast, parents who have difficulty setting limits may display weak or even discrepant signals that are difficult to read and are confusing to the toddler. An ambivalent parent may smile as they say, “Now, don’t throw your food, honey!” Some toddlers may be confused by this mismatch of signals. Others may know what is expected of them, but continue on with their disruptive activity suspecting that there are no consequences to their actions.

4.1. Universality of emotional expression

For many years, there has been an argument about whether facial expressions are universal or specific to cultures. One way to study this is by observing cultures that have had little contact with other cultures. Although people in such cultures do not display any facial expressions that are not observable in other cultures, there are certain standards or norms that individuals follow in expressing emotions.

Ekman and Friesen (1969) have termed these “display rules.” These are cultural norms that are internalized about when, where, and how an emotion is displayed. Therefore, affective expression will vary considerably depending upon socialization and cultural norms. For example, in Western cultures, males are not expected to cry and females are generally expected not to display anger. In some societies, joy may be expressed through an uplifted body posture, laughing, large body movements, and loud vocal exclamations while in others, a simple smile may be all that is observed. Regardless of culture, there are certain facial expressions of emotion that are universal (

Izard, 1971). The facial expressions that are universal to all cultures are fear, surprise, anger, disgust, distress, and happiness. There is less universality for interest, contempt, and shame.

4.2. Developmental differences in affective expression

Neonates are capable of expressing a wide range of emotions including interest, distress, disgust, and pleasure (

Izard, Huebner, Risser, McGinnes, & Dougherty, 1980). Young infants are able to express positive affects including interest and enjoyment. They can also express negative affects including distress, disgust, fear, anger, and shame.

Baby cries are heard in the first few minutes of life, however, different types of cries and cry expressions related to different negative affects (sorrow, fear, anger, pain) develop as the child matures. This differentiation in emotional expression occurs for all emotions and relates to the individual learning to attach different meanings to events.

5. The socialization of emotions

Some primary emotions appear to be innate, however, they become adaptive over infancy, particularly through socialization. Affect is learned very early in life and becomes appropriate according to demands placed upon the individual. For the infant, this occurs

in parent–infant interactions. Up to 6 months of age, the infant’s facial expressions are highly changeable or labile, changing every 7–9 seconds (

Malatesta & Haviland, 1982;

Malatesta, Culver, Tesman, & Shepard, 1989). This high variability in expression gives the caregiver many opportunities to respond and shape emotions. Mothers actually respond to about 25% of their infant’s facial expressions with a lag time of less than 0.5 second. This is the time most optimal for instrumental conditioning. Most mothers will show a dissimilar affect than their babies and imitate their baby’s expression only 35% of the time. Mothers tend to reinforce positive emotional expressions through smiling and talking to their infants, particularly in younger infants (i.e., 3 month olds). By 6 months, mothers do less nonverbal acknowledgment of their baby’s affect.

This information is important in our work with children. We need to be aware as therapists that our facial expressions are highly changeable and that we only reinforce about 25% of our client’s facial expressions. As a result, in treatment of some individuals, we may purposely slow down our affective expressions so that the child is better able to process our affect and we may choose to remark on certain emotional expressions in our client at helpful moments. Noticing subtleties in affect, such as a tearful eye, a fleeting grimace, a choked voice, or the child sipping water to soothe themselves may be clues to the person’s true emotional core.

Facial expressions of infants are signals to their caregivers to communicate with them. The competent infant becomes adept at providing clear signals to the caregiver when expressing needs, but the caregiver must also be sensitive in reading and reacting to these signals. When an infant displays a high-intensity expression, parents tend to engage in more stimulating interactions with their babies.

What happens when the infant is less capable of expressing affect because of motor problems? Mothers of Down’s syndrome infants tend to compensate for low-intensity expressions by becoming more stimulating in their interactions with their babies. Parents of infants who appear less alert or less responsive may try to compensate for their infant’s diminished emotional expressions by overstimulating them (

Sorce & Emde, 1982). These types of infants are less emotionally available and tend to be less rewarding for the parents.

In contrast, what happens to the parent–child interaction when the infant is irritable? In our study of mother–infant interactions, we found that mothers of regulatory disordered babies were likely to engage in more anticontingent responses (e.g., doing opposite of what baby was seeking) and tended to overstimulate their baby by talking a lot rather than engaging in active play (e.g., symbolic play or rough housing). The mothers also appeared depressed by showing flat affect (

DeGangi, Sickel, Kaplan, & Wiener, 1997). It seems that these mothers were more comfortable using distal and verbal modes of communication than proximal, gestural, or sensory modes of communication. They seemed to have difficulty reading their infants’ signals, in responding in a contingent manner, and in facilitating their infant’s representational capacities. In everyday situations, this

may affect the mothers’ capacity to support their children’s abilities to self-regulate or organize planned actions to manage distress. The infants with regulatory disorders had difficulty responding in a contingent manner and in providing effective gestural, affective communication during sensory play situations (e.g., play with textured toys). Their behaviors and communicative signaling may evolve around their experience of distress, sensory hypersensitivities, and the ability to cope with heightened levels of positive and negative emotions. The result is a miscoordinated interaction between mother and child that includes asynchronous, disengaged behaviors.

5.1. The inhibition of affective expression

It is possible for a person to inhibit expression of emotions when trying to conceal their reactions. Usually the person cannot totally inhibit the internal feelings recruited by an emotion although they may be able to combat a bad mood by engaging in certain activities (i.e., exercise, exciting activities). Oftentimes, the person’s voice will reveal their true emotions even if they manage to keep a poker face. For instance, a person may be telling you about a very stressful event in their life and saying that it no longer bothers them, but you can detect a quivering or a cracking in the voice even though they are smiling as they talk. It is also harder to inhibit signs of emotion in the face than it is in the body. A person who is feeling depressed and sad may be able to keep an uplifted body posture, but their face will often give away their sad mood.

5.2. Neural mechanisms mediating affective expression

Affective expression does not suddenly emerge, but rather it is the integration of cognitive, perceptual, and motor skills. This occurs as the result of increasing functional connections between specific brain regions instead of emergence of specialized localized brain centers. The right hemisphere is specialized for voluntary facial expressions, such as posing for a picture. These types of deliberate or voluntary facial expressions involve visual–spatial skills (i.e., knowing what a smile looks like, then assuming one). Interestingly, deliberate facial expressions that are expressed without the corresponding emotion are usually asymmetrical as opposed to spontaneous ones. For instance, a deliberate smile tends to be stronger on the left side of the face in right-handed subjects (

Ekman, Hager, & Friesen, 1981). Timing also differs. For instance, the expression may be too short or too long and the onset and offset may be abrupt. Think of the person who is trying to be cheerful but feels depressed. They may put on an exaggerated smile of the lips but without the wrinkling around the eyes that goes with a spontaneous smile. Or the person may have a fake laugh that is too loud and too long.

A number of studies have reported that the left side of the face dominates affective expression—that is, the left side of the face shows greater facial movement and is more intense than the right side during spontaneous emotion. Most investigators have attributed this to right hemispheric lateralization for emotion (

Fox & Davidson, 1984).

Both hemispheres contribute differentially to the experience and expression of positive and negative emotions. States of positive emotion are associated with left frontal activation while states of negative emotion are associated with right frontal activation (

Davidson, 1984). The left hemisphere also plays an important role in the inhibition of negative affects by suppressing right hemispheric activity. This inhibition begins when children develop verbal fluency, around 18 months of age.

The emergence of different emotions also follows a developmental progression that relates to neural maturation. The emotions of interest and disgust appear to be under unilateral hemispheric control and are present in the newborn at a time when there is little functional interconnection between the hemispheres. Fear and sadness usually do not emerge until the end of the first year when interhemispheric communication is developing. However, a child who has been maltreated by caregivers, or hospitalized for a serious illness, or whose caregiver is seriously depressed may suffer from an anaclitic depression in the first year of life. The onset of locomotion, a behavior associated with commissural communication, also occurs with the emergence of fear. The baby is not only able to experience fear but can escape fear-provoking events with efficiency. Expression of sadness usually develops in the second year of life and is associated with alternation between approach and withdrawal, thus implicating interhemispheric communication (

Fox & Davidson, 1984).

Feedback from the body may serve to help regulate affect. Certain body postures give more feedback than others. For example, a “sad” body posture with collapse into flexion causes the least firing of proprioceptors in the neck and trunk. A “happy” posture causes a high degree of proprioceptive discharge from the extensors. It is used therapeutically when we use muscle relaxation techniques on the highly anxious or hyperaroused individual. Through a change in body posture, the goal is to help the person to unblock negative emotions or to alter arousal for more focused purposeful attentive behavior.

Children with sensory integrative dysfunction, especially problems related to muscle tone and motor planning, are likely to have difficulty in modulating affective expression because their bodies do not provide accurate feedback related to postures that accompany facial expressions. Sometimes there are major implications for the child. The following case example depicts how these problems might play out.

Patricia was a very bright 6-year-old child with severe motor planning problems. She appeared happy and content, but experienced enormous frustration that she was so accident prone and slow to learn things that should be automatic (e.g., riding a bicycle). She was just beginning to dress herself and was still struggling with tasks like tying her shoelaces and buttoning her clothes. Patricia had developed high anxiety, behavioral resistance, and learned helplessness related to any task that required motor planning. For example, Patricia was afraid of heights that affected her ability to climb stairs. When she would climb a flight of stairs at home, school, or other places, such as a museum, she would become overwhelmed with fear. Instead of using her words to say she was afraid, she would cling to her mother or father and say she had to go home right away, saying that she was going to vomit. She did, in fact, sometimes become motion sick in the car and would experience autonomic reactions to movement (e.g., feeling like she would vomit after swinging on a swing). Patricia did not like to take any risks and appeared to derive satisfaction from activities when she was involved vicariously. For example, she would command her parents to dress her dolls in certain outfits, changing their clothes several times in a row, then she would want them to set up her doll house in a particular way, often changing her mind and wanting them to set it up all over again. If they did something different than she wanted, she would yell at them loudly and begin to throw tantrums. Patricia was a child who often assumed a watchful role in her life activities, but when she engaged with others, she would often become intense and verbally aggressive. It seemed that the lack of adequate sensory feedback that she experienced from her body coupled with severe motor planning problems contributed to her strong sense of inadequacy and inability to modulate affect. She seemed to function at two ends of the spectrum—either passive and submissive or screaming and intense. Becoming more attuned to feedback from her own body while working on appropriate ways to control others and the environment were emphasized in her therapy program.

6. Modulation of emotion and mood states

The modulation of emotion is intimately connected with the process of “self-directed regulation” (

Tronick, 1989,

2007). When a person is developing a new skill or lacks prior knowledge of the meaning of a situation, they tend to rely upon others for cues to communicate emotional meanings. For example, an infant is reaching for an out-of-reach toy. Soon the infant feels frustration, fusses, and is on the verge of quitting. However, the father, observing this activity, encourages the baby to continue reaching until he has successfully attained the toy. The father’s encouragement served to motivate the baby’s persistence while deterring frustration, tantruming, or other negative behaviors in this example.

As the child develops, self-directed regulatory behaviors emerge (

Gianino & Tronick, 1988). These involve the individual’s internal capacity to shift negative emotions to more positive ones to allow for goal-directed activity. The infant who engages in self-calming techniques, such as sucking his thumb, or looking away momentarily before resuming the activity may be able to persist in reaching for the toy on his own without the father’s encouragement.

6.1. Regulation of negative affects

Kopp (1989) has further delineated the development of emotion regulation. It involves the use of an action or behavioral scheme, such as vocalizing, self-distractions, manipulating an object, or removing oneself from a situation. These actions help to diminish the individual’s state of arousal that are related to distress. The child gradually learns a variety

of adaptive mechanisms that help organize and monitor the child’s actions and regulate negative emotions. For example, when presented with a challenging situation, a person often uses strategies that worked before. If the strategies are successful, the person is able to inhibit feelings of frustration and anger that would occur otherwise. An adaptable infant may close his eyes and avert his head when having his face washed instead of crying. A toddler may hold his hands together or put them in his pockets when told that he cannot touch a fragile object, thus inhibiting himself in an adaptable way. A child struggling to master a very difficult task may take a break to refresh him or herself mentally and physically, thus avoiding a tantrum.

6.2. Emotion regulation and adaptation

The emotions that an individual experiences while engaged in activity further serve to regulate the individual’s ability to adapt and respond to the situation or activity. Suppose a person experiences interest, pleasure, or mild anxiety while engaged in a task or social interchange. The experience of these emotions will help to support persistence and continual engagement. If, on the other hand, the person experiences intense or negative emotions, such as anger, fear, extreme frustration, or high anxiety, these emotions will interrupt or disturb the individual’s ability to engage further in the task or they may seriously impede the person’s performance.

Another important way that we regulate emotions are in relation to our own internal goals. They help us to evaluate our success in accomplishing our goals and motivate our activity in further pursuit of our goals. Internal goals may be immediate in nature and relate to security and basic homeostasis. For example, a high-risk family may be faced with putting food on the table and finding shelter. Another internal goal may be sharing interactions with others. For example, the young child may bring a toy to his father hoping that he will play a game with him. We also have internal goals for mastery and accomplishment of skill. While learning a new skill, a person may experience frustration and anger. Picture the person learning to play golf who continually misses the ball and hits the ball into the woods and sand traps. On the other hand, a person may feel a positive emotional state while learning a new skill—such as joy and interest—which further motivates engagement in the activity. Take the young child who is learning how to crawl or walk and practices this skill over and over again. But if there is a block or an obstacle in the way that is too difficult to overcome, such as a gate blocking entry to the stairs, the infant may become distressed and angry. After a while, if the infant cannot overcome the obstacle or an adult does not respond to the baby’s expression of distress, the infant may feel defeated, sad, and eventually withdraw from the situation.

6.3. The role of arousal in the socialization of emotions

The infant’s first goal is to learn to tolerate the intensity of arousal and to regulate his internal states so that they can maintain the interaction while gaining pleasure from

it (

Sroufe, 1979). This has been described as “affective tolerance,” that is, the ability to maintain an optimal level of internal arousal while remaining engaged in the stimulation (

Fogel, 1982;

Fogel & Garvey, 2007). The parent acts to help regulate this arousal, then works to facilitate the infant’s responses once the infant can regulate himself. If the infant does not develop affective tolerance, withdrawal from arousing stimuli may lead to a pattern of disengagement with resulting insecurity in attachments.

Brazelton, Koslowski, and Main (1974) have observed how the mother attempts to adjust her behavior to be timed with the infant’s natural cycles. For example, mothers generally reduce their facial expressiveness when the infant gazes away, but will maintain their expressiveness when the infant looks at them (

Kaye & Fogel, 1980).

Field (1977,

1980) has proposed an “optimal stimulation” model of affect and interaction. If the mother provides too much or too little stimulation, the infant withdraws from the interaction. The optimal level varies considerably from one infant to the next and depends upon the infant’s threshold for arousal, tolerance for stimulation, and ability to self-control arousal. If the mother maintains the infant at an optimal level, an interchange of smiling and gazing occurs. An increase in the infant’s attentiveness may relate to the mother becoming less active and more attentive to the infant’s gaze or when the mother engages in imitations of her infant’s behaviors. When the mother becomes more active, the infant tends to be less attentive. Adults also seek to modulate their arousal during interactions in similar ways. For example, two friends talking in a highly stimulating environment, such as a crowded shopping mall may look away intermittently from the person speaking.

6.4. Mood regulation

What is the difference between emotions, feelings, and moods? Emotions are brief in duration—most last only a few seconds. Most facial expressions are also brief except when they are very intense (e.g., crying, laughing hysterically). The autonomic nervous system changes that occur during an emotion may last longer than the emotional expression but do not persist for more than a few minutes. For example, when a person becomes very angry, they may feel “angry” after they have expressed their anger. The visceral responses associated with anger usually last longer than the actual expression of the emotion. The longer an emotion is experienced, the stronger the person reports the feeling of a particular emotion. When angry feelings last for a duration of time, perhaps an hour or more, then it becomes a mood. In emotional disorders, duration becomes important. In addition, the individual becomes prone to being flooded by a particular emotion—depression, anger, anxiety. Flooding is the phenomenon when almost any event will elicit the emotion. Sometimes the emotion will reappear without any particular stimulus. When this happens, the emotion is intense and interferes with everyday functioning (e.g., sleep patterns, eating, work tasks, social interactions). The person will also have difficulty dampening the emotion and shifting to more positive, productive emotions.

Moods do not have a facial expression. For example, a person who is feeling irritable may become angry very easily and stay angry longer than a person who is not irritable. The irritable mood though does not have a distinct facial signal. When a person has a predominant mood, such as feeling depressed, they will typically show a high frequency of sad expressions (

Ekman, 1984).

Moods may be produced in different ways. Changes in biochemical balances, such as diet, disease, fatigue, exertion, or a stimulating sensory experience can produce different mood states. For example, if a person is tired, they may be more irritable. Or a child who rides on a series of carnival rides may become very hyperexcitable and happy. If a particular emotion is elicited repeatedly over the course of a short period of time, it may produce a biochemical change that causes a mood state to prevail. If a person has experienced a series of maladies in a row, they may become angry and irritable over time.

The feelings that are associated with emotions may be anticipatory in nature, such as anticipation of an exciting event (i.e., opening a birthday present). It may also be anticipatory dread or fear (i.e., presenting a speech in front of a large audience or an upcoming piano lesson after not practicing for a few weeks). Feelings also occur while an emotion is being expressed. Oftentimes, we hear people express these verbally while engaged in an activity. For example, we hear children exclaim, “This is fun!” Feelings may be elicited by memories of the event. Certain words, smells, or places often evoke strong feelings of past events. Sometimes children reared in institutional settings, such as an orphanage in Russia remember things from their very early childhood based on certain sensations or smells. For example, 5-year-old Katarina cried and stated, “You’re not going to tie my hands down, are you?” when her parents went to a hotel and showed her a spring mattress that she would be sleeping in. Evidently the spring mattress must have reminded her of her early days in the orphanage when she was restrained in bed.

7. A developmental–structuralist approach to organizing sensory and affective experiences

In this next section, the developmental–structuralist approach is presented. This approach incorporates the organizational tasks and adaptive and maladaptive infant and caregiver patterns observed in the first few years of life (

Greenspan, 1979,

1989,

1992;

Greenspan & Lourie, 1981;

Greenspan, Wieder, & Simons, 1998). It emphasizes the link between sensory and affective-thematic experiences which help the child to organize and regulate emotional processes.

In this model, there are three essential levels of emotional development. In the first level, the child learns to become socially engaged, but in doing so must learn how to self-regulate by developing homeostasis and forming an attachment to the primary caregivers. The next level is one in which the child develops intentional organized behaviors. The important milestones of this level include development of flexible reciprocal interactions, purposeful communication, an understanding of causal relationships, and development of self-initiated organized behaviors. The last level involves representational capacity, its elaboration and differentiation. In this level, the child shifts from organizing concrete behavioral patterns to symbolic representations of events, objects, and persons. The child begins to learn how to label feelings and emotions and elaborate upon them, and expressing emotions related to themes, such as dependency, pleasure, assertion and autonomy, anger and control, empathy and love. These three levels of psychosocial development are described in this next section.

7.1. Level of engagement: homeostasis and attachment

The infant’s first task is to take interest in the world and regulate himself in terms of states of arousal and feeding and sleep cycles. Self-regulatory mechanisms are complex and develop as a result of physiological maturation, caregiver responsivity, and the infant’s adaptation to environmental demands. In the early stages of development, the caregiver soothes the young infant when distressed and facilitates state organization. Early sensory experiences are important in helping the infant to differentiate pleasant and unpleasant experiences. For instance, being fed and cuddled is usually a comforting experience whereas wearing a wet diaper is not.

The capacity for engagement and attachment has to do with both physical capacities of the infant, such as the ability to modulate and process sensory experiences (including visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, vestibular, proprioceptive), and the ability to coordinate simple motor actions, such as reaching for the caregiver’s face. The infant learns to engage in mutually satisfying experiences with the affective world. For example, the parent may play reciprocal cooing games with his or her baby. As the infant learns to regulate states of arousal, he can focus attention to take interest in the world while also adapting to a variety of sensory stimulations experienced in everyday life (i.e., being held and carried, fed, or bathed). As the caregiver provides soothing and organizing sensory and affective experiences for the baby, the infant forms a special emotional interest with the caregiver.

Problems at this early stage can have wide-reaching implications life-long. For instance, Sylvia was distraught when a favorite aunt offered her 7-year-old child a birthday present, something that delighted her daughter but upset Sylvia very much. She couldn’t seem to explain her emotional reaction, but she felt furious at the aunt for giving a gift to her daughter with such warmth and caring. Sylvia had suffered from emotional deprivation growing up and never experienced being given to and nurtured in pleasurable ways. On a cognitive level, she knew that she should be happy that her daughter was receiving something she didn’t get as a child, but on a visceral level, it made her feel neglected.

7.2. Level of intentional, interactive, organized behavior, and affects

This level spanning from 8 months through 18 months includes the stages of somatopsychological differentiation (intentional communication) and behavioral organization. This level lays the foundation for formation of a complex sense of self. The baby becomes increasingly more purposeful and organized in interactions with the object and person world. The child begins to attach emotional meanings to different sensory, interactive, play, and caretaking experiences. For example, the 8-month-old may reach out to be picked up, then smiles when his wishes are met. By 18 months, the toddler begins to understand that their mother or father are sometimes loving and nurturing, sometimes firm or even angry, and other times playful. The child still relies on concrete experiences and is oriented on here and now experiences because he has not yet developed the capacity to represent his thinking, emotions, and behavioral experiences.

An important hallmark of this stage is the development of intentional organized communication to human interactions. We observe the child engaging in interactive signaling with others through gestures, words, and actions. For example, a 9-month-old often enjoys the game of tossing his cup and plate onto the floor while sitting in the high chair. At first it may become a playful game, the infant gesturing toward his cup on the floor and smiling as his father returns it to his tray. But if the dad tires of the game and ignores baby’s wishes to continue the game, the baby begins to clench his fists and look angry, even banging on the lap tray to show his anger. Through these interactive exchanges, the baby begins to organize and communicate emotions, such as assertiveness, curiosity, anger, dependency, and pleasure. By 15–18 months, interactive signaling becomes more organized. The toddler can communicate not only in proximal space, but also in distal space. The toddler may toddle across the room to knock down a large block tower, then look over to see if his mother noticed him. If the mother smiles admiringly and tells him, “What a big boy!” the toddler interprets her words and gestures as encouraging. This distal connection with the mother, also known as social referencing, enables the toddler to continue playing from across the room without having to go back to sit on mom’s lap. He can feel her reassuring presence through her approving nods. He can gesture to her about feelings of frustration or anger when he can’t successfully build the block tower, such as throwing the block and scowling.

During the level of intentional organized patterns, the toddler learns to use complex preverbal gesturing and sounds to engage with his world in a new way. Communications become reciprocal in nature and the toddler learns that he can give and receive information from others through different channels (e.g., gestures and words, as well as sensory and motor experiences, such as rough housing with father). The toddler communicates emotional meanings through these channels. For example, he may challenge the limits of safety by testing whether he can touch an electrical outlet at home or unbuckle his seat belt while riding in the car. He may look for reassurance and acceptance by putting away her book on the shelf. Many of the important life messages are learned during this stage including love and approval versus hate and rejection, safety versus danger, and a respect and empathy for self and others versus impersonal detachment.

Many children with mood dysregulation including those with autism spectrum disorders, ADHD, or those who have suffered abuse, neglect, or trauma often do not develop the capacity for interactive signaling, reciprocity, and the ability to integrate thoughts and feelings for adaptive social behavior. They may lack a sense of self and be unable to differentiate the range of emotions, such as assertion and needs for dependency, self limit setting, or empathy.

7.3. Level of representational elaboration and differentiation

During the representational stage occurring between 18 and 30 months of age, the child creates mental images from actions, events, and sensorimotor experiences and internally manipulates them through thoughts, communication, and new actions. The child begins to represent ideas through pretend play and articulation of abstract ideas. The emotional meanings of life that were previously explored through two-way communication now become symbolized. The child can explore the meanings of different emotional experiences including dependency, pleasure, assertiveness, anger, and self limit setting. The child is now able to attribute affective meanings to objects, people, and events. For example, the child learns that weekday mornings have a different pace to them because mom and dad are bustling about. He may resist getting dressed to avoid having to go to the babysitter’s but on the weekend, he quickly helps his dad get him dressed to go to the park. The child begins to express complex emotions, such as empathy and an internalization of love for self and others. These emotions become stable and survive emotionally upsetting experiences, such as separations and tantrums. Later on, the child develops the ability to experience loss, sadness, and guilt.

During this stage, the child attaches meaning to concrete events. For example, the toddler can label pictures (e.g., “D.W. is happy. She found the ring.”) and describe objects in affective terms (e.g., the scary monster, the favorite stuffed animal). He can also describe his own feeling states (e.g., “I want that,” “my turn”). As the child moves into pretend play, he or she can enact simple to complex dramas that reflect everyday sequences and their meanings to the child, such as feeding the dolls, going to the store, then coming home to sleep. Older children do the same thing through story telling, poetry, or art.

As emotions become differentiated and the child has a stronger sense of himself and others, experience becomes categorized into functionally relevant patterns. As the child can communicate through words and pretend play, wishes and emotions are expressed. The child can shift between fantasy and reality in play (“that’s pretend, isn’t it?”). He also learns to understand his impact on others (i.e., saying sorry when he spills his juice on another child).

8. Application of developmental–structuralist model

This last section focuses on the functional application of the material presented in this chapter. In the first part, different emotional problems of children are discussed from the point of view of the three levels of somatic-affective experience described by Greenspan. A case example is used to depict problems that may occur at each level and how the clinic could intervene. Following this, concrete suggestions are provided for working with different problems related to mood regulation and irritability. Three case examples are provided that integrate the components of the model spanning from infancy through early adolescence.

Dr. Greenspan’s seminal work in the field of ego psychology has provided mental health and early intervention professionals, as well as families with children with special needs an important way of conceptualizing the child’s emotional and developmental needs and how to translate this into treatment. For example, is the person engaged or not engaged, in what situations do these occur and how do they engage or disengage? How does the person communicate—through gestures, affective expressions, and words? Does the person organize affective experience symbolically? By observing individuals along dimensions of engagement, intentional behavioral patterns, and representational elaboration, the clinician can conceptualize how to address the person’s difficulties. For example, if the child has a fundamental deficit in the capacity for engagement or gestural communication, one may concentrate on these more basic areas. If the child has the capacity for representational thinking, one would work on building a foundation for interactions while also fostering the child’s symbolic capacities.

8.1. Level of homeostasis and engagement

Infants who are unable to process sensory experience in a normal fashion cannot utilize the range of sensory experiences available to them for learning. These infants oftentimes have maladaptive responses in forming affective relationships. For instance, an infant who is hypersensitive to touch, sound, and movement may avoid tactile contact, being held and moved, and may avert his gaze to avoid face-to-face interactions.

The ability to engage can be compromised by several things. There may be difficulties in sensory modulation or processing, such as the baby who is sensitive to touch or high-pitched sounds and who avoids or withdraws from the human world. Difficulties with muscle tone or coordination can affect the infant’s ability to signal interest in the world. For example, the young infant who arches away from the mother’s breast during feeding due to oral hypersensitivities or an imbalance in muscle tone will affect the level of engagement that occurs during feeding. These problems in the infant will affect the caregiver’s ability to respond, particularly when they do not understand what the baby’s responses mean. The mother whose baby arches away when he is held may feel that she is being rejected or that she is not a good mother, particularly if the baby’s tactile hypersensitivities or increased muscle tone are not understood.

Even when the infant is competent from a sensorimotor standpoint, a caregiver might fail to draw a baby into a relationship (e.g., a caregiver who is depressed or who is self-absorbed may not woo their new infant). This can have lifelong implications for the person. For example, Carol’s mother was an alcoholic who was more concerned about her own social life than raising her three children. The father traveled and was rarely home. Carol’s mother frequently abandoned the children to go out to parties and left the house in chaos with no food for the children to eat. As Carol grew up, she observed the horrible disrepair of the household, the stark neglect from her mother, and felt that she was worthless, undeserving, and unlovable. When Carol became a mother, she was constantly getting into battles with her husband, children, and family members, not knowing how to be in a mutually rewarding and reciprocal relationship. She struggled with how to provide a nurturing and stable home environment for her own children which was the focus of our work together.

Physical traits, temperament, ability to self-regulate, sensorimotor capacities, and interactive capacities can have a significant role in the baby’s capacity for engagement. Variations in the capacity for engagement are often a central aspect that underlies different types of psychopathology in later childhood and adulthood. Difficulties that are encountered at the level of engagement, may be evidenced by a lack of relatedness to the human world. For example, the child may appear aloof or distant, “beating to their own drummer” as Greenspan describes, or they may be autistic-like. One can observe the quality of engagement in terms of its stability and how well it is maintained when challenged by stress or demands. For example, a child may remain engaged in play as long as it is the child’s agenda, but as soon as the adult requires the child to follow a routine, make a transition, or adhere to any other demand, such as cleaning up, the child may become disengaged. For some individuals, the stress that causes them to disengage may be certain types of sensory stimulation (e.g., loud noises, someone touching them in an effort to be close). The qualities of the engagement may also vary depending upon the challenges that confront the child. For example, the child may appear mechanical in their interactions, emotionally labile, or very demanding of attention from others.

8.2. Level of intentional, interactive, organized behavior, and affects

A child with difficulty at this level will have disorganization with gestural signals and intentional behaviors. The child may interact but not purposefully. For example, play may be stereotypic, perseverative, or appear unfocused or aimless in quality. The child may not respond to the caregivers’ signals, ignoring or misreading communications from others. Temper tantrums or withdrawal from interaction may occur if the caregiver does not respond to the child’s signals.

8.3. Level of representational elaboration and differentiation

Disorders in this phase include children who remain concrete and have difficulty using representational thinking. Impulsive or withdrawn behavior often accompany such a limitation. The child’s relationship patterns may be fragmented or there may be an overdependence, clinginess, and inability to separate from the caregiver. The child may also show little range of affective elaboration. For example, play may focus exclusively around aggression and the child may appear solemn, stubborn, or angry. Some children may be highly impulsive with acting out behaviors as observed in conduct disorders. The following section presents a case example of a child with difficulties in the various emotional stages described earlier.

9. Case example of a child with difficulties in various emotional stages

Philip was a very verbal and imaginative 6-year-old child. He was charismatic and liked dramatic play, sometimes dressing up in hats to be policeman, fireman, or superman. Philip had difficulties with social skills. He played well with peers as long as the play went his way, but when it didn’t, he would bully the other children and say, “Nobody can touch any of these toys!” He often misconstrued social signals (e.g., confusing accidental and purposeful touching) and would become aggressive with other children. He was anxious about making friends, yet he could be outgoing, introducing himself to others in a friendly way.

Philip was a hypersensitive child. If he got hurt, he overreacted strongly, screaming at his parents not to touch him. He showed signs of tactile defensiveness, such as hating haircuts, avoiding new food textures, and preferring long sleeved garments and pants even in warm weather. When in a group of children, Philip tended to withdraw. He was sensitive to loud noises and seemed to have difficulty focusing at school, going from one thing to the next. When not engaged in an activity, he often zoned out watching TV. There were subtle indicators of motor planning problems. For instance, Philip was fearful of riding a bicycle. He did not like unexpected movement, was frightened of falling, and disliked trying new movement activities.