Chapter 7

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: How to Build Flexibility and Budge Compulsive Thinking

Abstract

Obsessive–compulsive disorder is a serious illness that affects one’s ability to control thoughts and behaviors because of irrational fears. Obsessions are persistent, repetitive thoughts that can be meaningless or frightening to the child. The child worries that if he doesn’t engage in a particular ritual or repetitive behavior, something even worse will happen. They can be consumed with self-doubt that something harmful has happened or will happen to them.

Keywords

obsessive–compulsive disorder

irrational thoughts

obsessive rituals

exposure therapy

positive self-talk

1. What is obsessive–compulsive disorder?

Obsessive–compulsive disorder is a serious illness that affects one’s ability to control thoughts and behaviors because of irrational fears. Obsessions are persistent, repetitive thoughts that can be meaningless or frightening to the child. The child worries that if he doesn’t engage in a particular ritual or repetitive behavior, something even worse will happen. They can be consumed with self-doubt that something harmful has happened or will happen to them.

These repetitive thoughts can come suddenly or have a gradual onset. At first the thought may seem connected to a real event, but often it morphs into something that is purposeless and may even be bizarre. For example, when it was on the news that a lady was shot by a sniper while vacuuming her car at a gas station, Stephanie developed extreme fear that this could happen to her mother. At first she insisted that her parents drive long circuitous routes to avoid the gas station despite its location near her middle school and gymnastics class. By the time Stephanie was in high school, she continued to hold the fear that this could happen to her mother or herself, long after the sniper had been executed, and continued to duck in the car and requiring her mother to avoid driving past the gas station. Other fears developed that were associated with this incident. At home she kept her curtains drawn at night for fear that someone might see her in her bedroom and shoot her. Stephanie had always had OCD behaviors and as a young child could be easily stimulated by a scary picture or movie that would set off all kinds of rituals. As a young adolescent she kept a closet full of special pictures to ward off evil and she was superstitious of certain numbers or types of events. She kept her OCD hidden until this sniper event, which unleashed a whole host of fearful thoughts.

Other times the OCD behavior may be irrational from the start like a child who has to tap or press his left foot into the floor the same number of times as his right foot to ward off bad luck, or perhaps for no reason at all. Usually the obsessive thoughts take on a thematic quality—that is, worries about germs, impending illness, food safety, or forgetting things. For other children, the obsessive thoughts may come and go and change from one threatening thought to another.

Typically the child who suffers from obsessive thinking is consumed with a strong feeling of self-doubt or uncertainty. They may not be sure of their own actions and need to continue to check to be sure that they did something like checking where they put a treasured toy or book that they just looked at an hour ago. Or they ruminate on an idea because they aren’t sure if it is true or not, then constantly seek reassurance from others. No matter how much they repeat the behavior or receive reassurance from others, they can’t seem to change the sticky thoughts in their brain. The child is plagued with repeating worries that they can’t get out of their mind. Most times the thoughts are quite irrational but they pervade the child’s belief system and ultimately impact their concept of self.

To cope with the overwhelming nature of their self-doubt, the child often gathers information by researching the topic, such as on the Internet or by excessive questioning of others. Despite the information they receive, they are still plagued with self-doubt as if the answers don’t register in their brain. It is an infinite loop in the brain. The child with OCD has the intrusive thought, they feel self-doubt, and then they seek information to quiet their fear. Perhaps the information they seek is not properly received by the brain to allow for rational behavior or reasoning. Or what underlies OCD may be ineffective suppression or screening of intrusive thoughts that continually rise to consciousness. It may even be a combination of these problems including a disturbance in information processing, rational thinking and conscious reasoning abilities, and the capacity to inhibit intrusive thoughts.

The irrational thoughts that plague children with OCD can vary considerably. Some individuals are quite aware that what they are doing is ridiculous but they simply can’t stop the thought or need to do a particular action. This is especially common with the child with an unusual ritual like tapping bathroom tiles in a particular order as they leave the room or picking up pieces of lint on a carpet. At the other end of the spectrum are children whose obsessive thoughts feel very real to them and they have a hard time distinguishing between the thought’s validity and actual reality. This is true for children with body dysmorphic disorder who believe that they are overweight if they weigh over a certain number even though they may be rail thin.

Children with OCD often engage in compulsive rituals in hopes of warding off bad luck or to quiet their anxiety. Gabby, at age 8, had a compulsive need to order her belongings in a particular way in her bedroom every time she left the house. She could not go to bed at night unless her clothes were folded neatly in the drawers, her necklaces and earrings organized in the jewelry box a certain way, and her shoes lined up in her closet in exact rows. There are also children who have to wash their hands repeatedly or say certain prayers to avoid harm, bad luck, or illness. One 10-year-old girl found that she had to do certain cleaning rituals, prayers, and kissing her family members good night in a certain way. If she was prevented from doing these rituals, she believed that someone would get sick with cancer and die despite the fact that everyone was healthy in the family. The majority of compulsive behaviors involve checking that something is right (readding numbers or making sure the back door is locked), counting in a prescribed manner (touching the mirror or tiles), ordering things in a particular manner (sorting and labeling food by categories in the cabinets), hoarding (stockpiling food, clothes, etc.), or repeating a certain pattern of behaviors in a prescribed manner, such as twisting hair in a special way, jiggling change in the pocket, or eating food in a certain order and manner.

In addition, many children with OCD engage in compulsive skin picking, nail biting, or hair pulling. In each of these habits, the child has a thought or belief that might drive the behavior (i.e., “I am not perfect enough”) and they experience an emotional state that accompanies the thought, usually high anxiety. Not only that, but the habit is reinforced on both a sensory (tactile, visual) and motor level, whether it is painful or pleasurable to the child. For example, Eva pulled large wads of hair behind her left ear whenever she felt that she hadn’t done something completely perfectly. The pain of hair pulling felt “good,” but she was also able to hide her habit from others because of her long hair. What was more obvious was that she was constantly picking hairs and threads off surfaces and other people’s clothing. When she was more agitated by the pressures of school or home life, she would pick at a blemish on her skin to the point that she had multiple red marks on her face, some of which would bleed. Eva was an avid nail biter as well, biting her nails down to the nail bed to the point that her fingers were frequently infected and sore.

Some children with OCD know that what they are thinking or doing appears odd, and then go to great lengths to hide what they are doing from others. They are fearful that others will think that they are disturbed or worry that others would embarrass them for their behavior. Sometimes they enlist their family in their habits and rituals to help keep the secret or they find activities or hobbies with a high degree of repetition or perfectionistic performance in an effort to normalize their behavior. In other cases, the sense of embarrassment is overwhelming so the child doesn’t tell others what is going on in their heads. They may suffer in silence which can compound their inability to cope. The longer it is untreated, the more generalized the symptoms become and take over the child’s life. For many individuals, they are overcome with a strong sense of shame and embarrassment. The OCD then becomes a deep, dark secret.

2. Is there a difference between healthy rituals and obsessive–compulsive behavior?

Rituals are part of healthy self-regulation and are frequently elaborated in families and cultures to have special meaning. They are a normal part of development. People frequently use rituals as a means of organizing themselves, coping with stress, and exerting control on people and the environment. For instance, children often have elaborate bedtime rituals, such as a set number of bedtime stories, throwing kisses to all the family members, then getting tucked into bed by their parent. As people grow older, they often continue special rituals especially around holidays and cultural and religious customs.

Healthy rituals help a child achieve self-regulation, rhythm, and regularity in daily living patterns. A well-balanced and well-regulated child will usually have fairly set times for important functions like eating, exercise, school, recreational activities, and sleep. Many children have hobbies that require repetitive actions. These serve a very organizing function to the nervous system. Knitting, beading, weaving, or drumming are few examples of this. During times of high stress, the child may have a stronger need for organizing rituals and hobbies with repetitive actions, such as surfing the Internet on certain topics. Children also develop an interest in having collections of things like coins, stamps, dolls, or comic books that might resemble hoarding. The distinction is that it is contained in time and space whereas the child who hoards cannot stop their urge to collect more and more items.

The difference between healthy rituals and OCD is when these rituals begin to increasingly interfere with the child’s ability to function. Rather than being adaptive and emotionally healthy for the child, the obsessions and compulsions take over an increasing part of the child’s activities and reflect consuming anxiety.

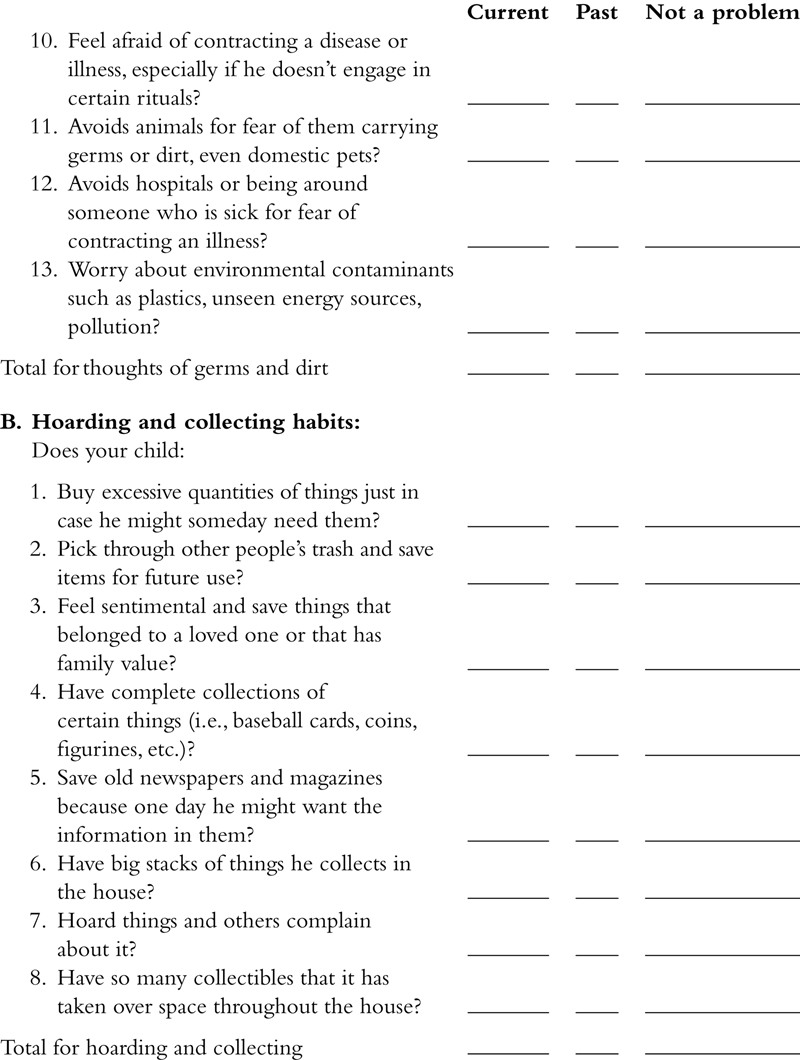

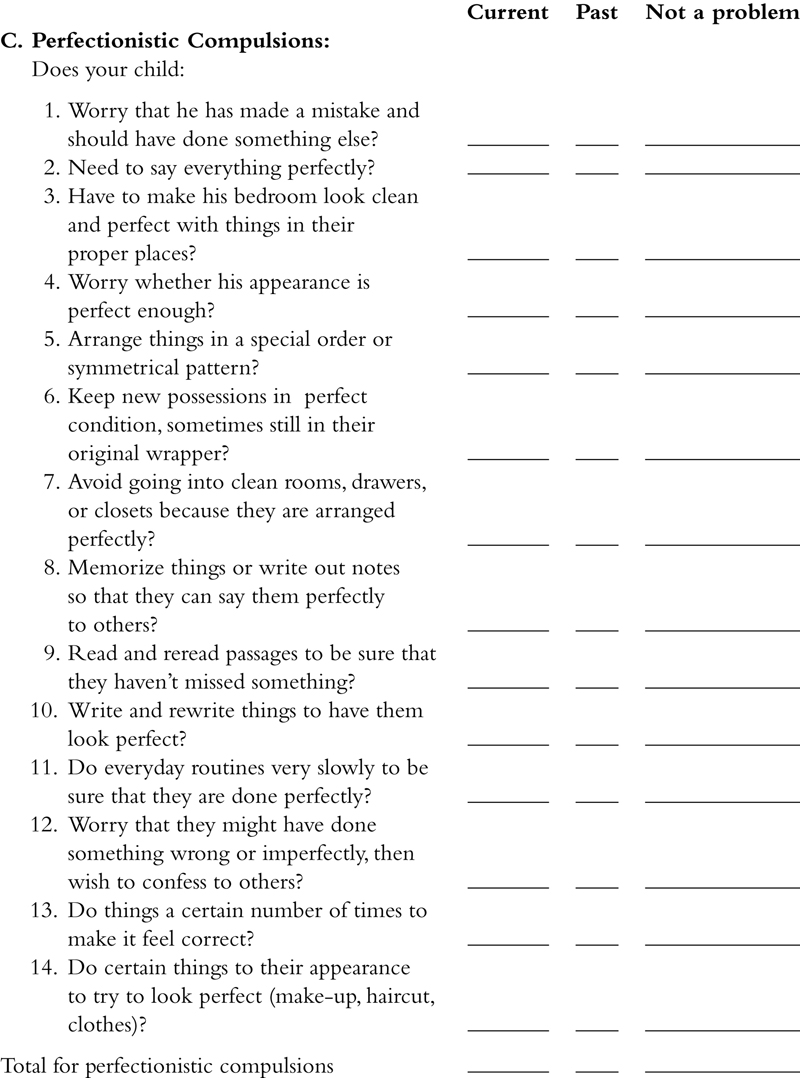

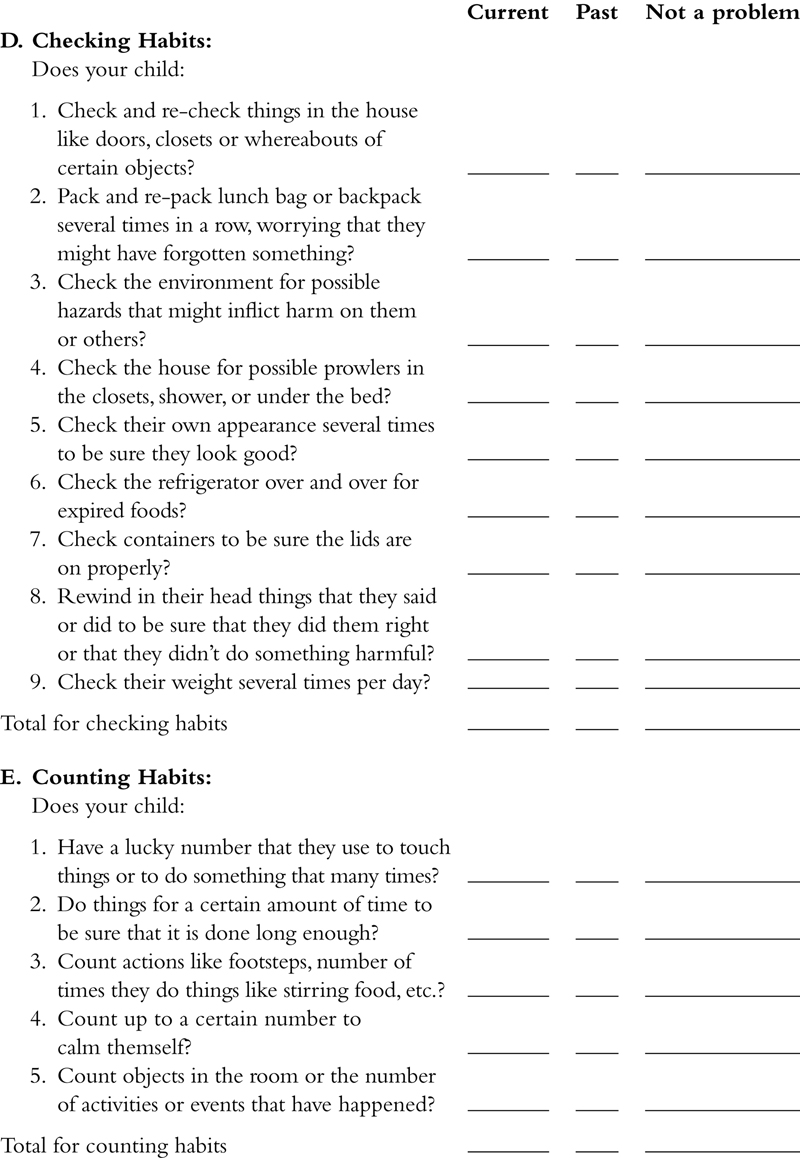

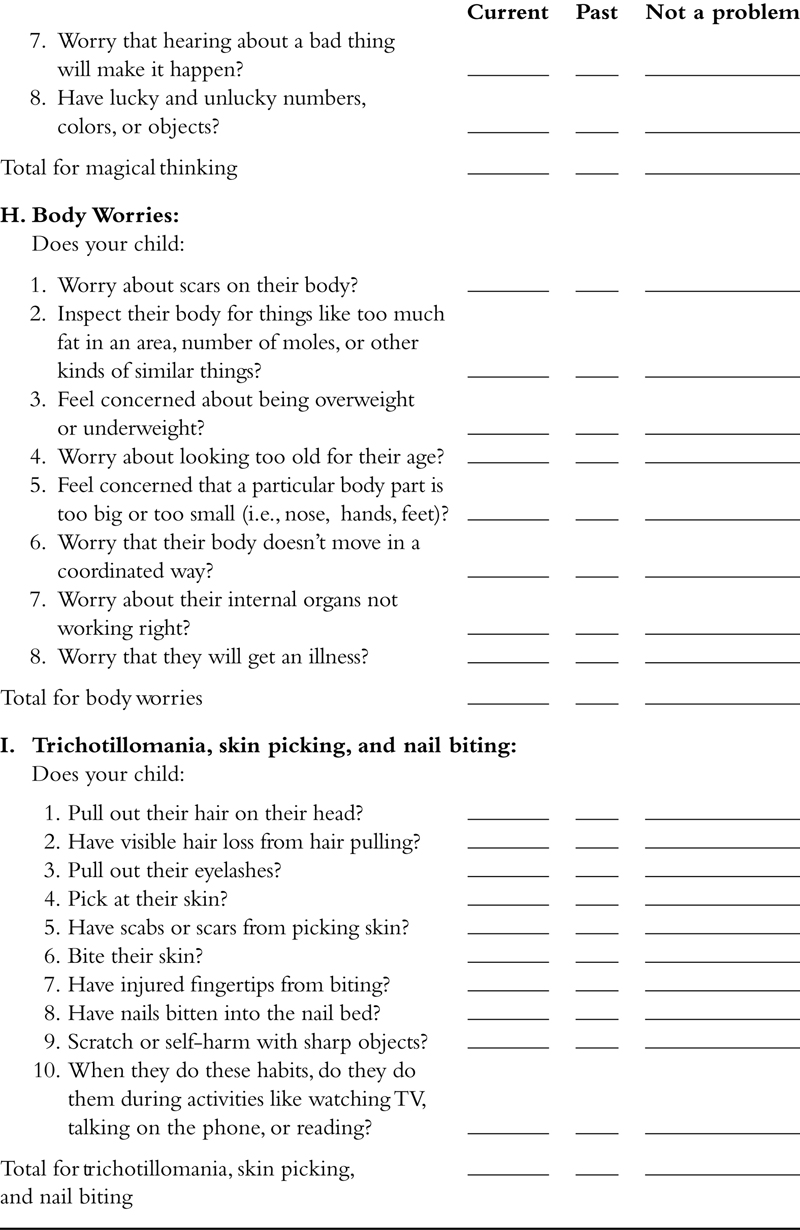

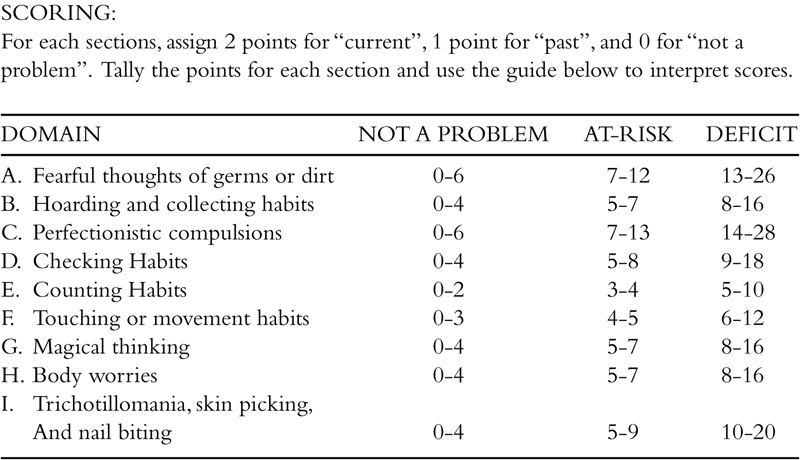

Here is a list of symptoms typical of children with obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorder.

The checklist at the end of this chapter can be used in helping to diagnose obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders.

3. What causes obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders?

It seems that OCD is the result of abnormalities in certain brain structures, neurochemical imbalance, and a genetic predisposition (Stein, 2008). Researchers have found that the neurotransmitter serotonin is abnormally low in individuals with OCD. When serotonin levels are low, it often leads to problems with mood regulation and control of aggression and impulses. Certain antidepressant medications have been found to work effectively on increasing serotonin levels and offering relief to children suffering from OCD. In some cases the medication makes the coercive thoughts go away entirely and decreases the accompanying anxiety. In most cases though, the medication alone helps to minimize the occurrence of repeating thoughts and the need to do compulsive actions.

The brain structures that are implicated with obsessive–compulsive disorder include the cingulate gyrus, orbital frontal cortex, the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. The amygdala plays a role in fear-conditioning. It receives sensory input that is perceived as threatening from the thalamus. It then signals the hypothalamus to engage in freezing or fight or flight reactions that are the essence of anxiety disorders, phobias, PTSD, and OCD. When the amygdala is overactive, it impacts cognitive activity in the prefrontal and orbital cortex. Equally important to the underlying behaviors of OCD is the cingulated gyrus, which allows the child to shift their attention from one activity or thought to another, to take perspective, and to think through other options in their behavior. The cingulate system enables cognitive flexibility, managing change, and planning and goal setting. When there is a problem in the cingulated system, it is apt to cause the child to perceive fearful situations, feel unsafe, and think negative thoughts. They tend to be very rigid, worry excessively, and get stuck on certain thoughts (Goldman, 2000).

When a child has OCD, the frontal lobe warns that danger is present. The cingulate gyrus responds and prioritizes the child’s thoughts and actions. When it is overly active, they get stuck on certain behaviors or thoughts. Judith Rapoport (1989a, 1989b) has described OCD as a “tic of the mind,” and in her research has found that these areas of the brain are also the location of other illnesses including epilepsy and Tourette’s syndrome, which cause tics in the body.

There is a clear genetic predisposition in OCD. Research studies have shown that 20–40% of persons with OCD symptoms have genetically linked relatives who share the disorder. This is especially true when there is a childhood onset of the disease (Geller, 1998).

In addition, recent research has linked childhood onset OCD to the bacteria that causes strep throat called Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococci, or P.A.N.D.A.S. The antibodies that attack the strep bacteria end up attacking brain tissue in the basal ganglia. In children, they may develop OCD-like symptoms but if the infection is treated by antibiotics, there is often significant improvement in symptoms. Interestingly, many adults with OCD report a history of strep infection as a child.

4. How can this disorder be treated?

In beginning the treatment of OCSD, it is very important to obtain a detailed history to understand the child’s symptoms. It is helpful to know what situations or settings elicit mental compulsions and obsessive behaviors and when the symptoms are at their worse. Not only is it important to enter the client’s world to understand what he is thinking, but to get a sense of how his behavior impacts family dynamics. It is not infrequent that the child is subjected to anger or emotional abuse from family members because of their obsessions. Or in other cases, the family may develop extreme measures to work around or support the client’s obsessions. The assessment stage should also involve naturalistic observations of environments where the behaviors are apt to happen.

A comprehensive treatment approach for OCSD usually involves a combination of medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy. The medications most commonly used for OCD are the serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which also include the tricyclic antidepressants and the serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors. A commonly prescribed medication for OCD is Anafranil (clomipramine), which works by blocking the reuptake of serotonin. These medications have been shown to be effective in eliminating or muting obsessive thinking.

When cognitive-behavior therapy is initiated, it is essential that the client develop a trusting relationship with the therapist. The therapy includes exposure to frightening obsessive thoughts, confronting the behavior in contexts that elicit the behavior, and learning how to inhibit compulsive rituals. Getting to the bottom of what drives the sticky thoughts and compulsive behaviors is very important. The therapy should be comprehensive and include homework exercises to practice behaviors outside of the therapy session. Not only that, but the therapy should emphasize helping the child learn how to stop and think, to live their life spontaneously and with pleasure, while also focusing on rebalancing their life to minimize stress and prevent relapse of behaviors.

4.1. Exposure and response prevention therapy

The most effective cognitive-behavioral technique used in treating OCD is exposure and response prevention. This technique is also helpful with children suffering from body dysmorphic disorder and anorexia. The technique is widely known as flooding and the basis of it is exposure to the situation that brings on the obsession while preventing the child from engaging in their compulsive rituals to decrease their anxiety. The therapy is set up so that the child learns to habituate to the feared event and sees that no harm has occurred to them. During the process of incremental flooding, the child’s fearful thoughts need to be processed and understood, regardless of how irrational they may seem. Gradually the child is subjected to feared events in a hierarchy of behaviors. The wish to escape or engage in ritualistic behavior is prevented so that there is an increased tolerance for what evokes the fear. Through this process of gradual exposure to feared events, over time the child begins to process and understand that no harm has been done to them. In essence, the child learns to tolerate their fear and see that it can be successfully lessened.

Exposure therapy alone can lead to a decrease in anxiety, but without response prevention coupled with exposure, less improvement may be seen with compulsive rituals. Likewise the reverse is true for response prevention. For the most effective treatment, the two should be combined together. As the therapist and client take the journey into treating the child’s fears and ritualistic behaviors, it is important that the program not push the child beyond their limits. All the while, the therapist needs to take the child’s pulse to know how the program is impacting family and personal life. It is very helpful if the therapist can be genuine, warm, and supportive through the treatment and whenever it makes sense, to incorporate a sense of humor to help the client know that you resonate to the frightening feelings that they experience.

5. Steps to overcome obsessive–compulsive disorder

5.1. Minimizing negative thoughts and the urge to respond: exposure to the feared situation or object

The most successful treatment for obsessive thoughts and actions involves exposure to the feared object or situation until one no longer experiences fear or anxiety about it. Exposure therapy operates on the idea of habituation. As the child experiences repeated exposures to the feared object or situation in tolerable increments without something bad happening to them and not escaping from it, their anxiety diminishes while they learn to tolerate exposure to the situation. The goal during exposure to the feared situation or object is to eliminate or minimize irrational fears. For instance, Abigail felt compelled to say prayers each night before she went to bed to prevent in her mind that something horrible would befall herself or her family. Abigail was a very spiritual child and prayer was comforting to her, however, we wanted her to not associate her need to pray with her fear that something bad would happen if she didn’t pray each night.

In exposure therapy, the therapist develops a hierarchy of fears with their client. Ideally it is a sequence of 10–15 increasingly more challenging acts or images that the child needs to do or be comfortable with in order to habituate to their fear. The hierarchy begins with items that are mildly troublesome to high anxiety items. Following is an example of a hierarchy for an individual suffering from a germ phobia.

After constructing the hierarchy, the child then rates their fear. Edward Wolpe, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Temple University School of Medicine, developed a scale called SUDS which means the following:

| S: | SUBJECTIVE |

| U: | UNITS OF |

| D: | DISTRESS |

| S: | SCALE |

The subjective units of distress scale ranges from 0 to 100. The therapist discusses with their client what would be a 100. For Allison, her germ phobia had become so extreme that her mother became a contaminant. Going into public bathrooms was a 100, just as sitting in her mother’s car after she had been out to a public place like the grocery store was. For her a 50 was to put her dirty towels in the hamper. A 10 was throwing away her unfinished meal, candy wrappers, or empty snack bags into the trash can. Using the hierarchy of fears and the SUDS measure, the client is gradually exposed to the items that he fears. The best way to tackle this is to begin with items that raise the SUDS to at least 50, then proceeding to increasingly more difficult items until the SUDS level reaches about 85. One wants to evoke discomfort in the practice of exposure therapy, but not so much so that they fall apart during or after the session. In contrast, too little discomfort will not evoke the fear.

As the therapist works with the client on exposure therapy, it is very helpful to engage in self-calming techniques, such as deep breathing, visual imagery, and tension release techniques to help diminish the fear. Repeated practice of certain events is often necessary to help the child habituate to the fear and to decrease the SUDS. It is like titrating the dosage of fear. Items should not go above 85 or the child will be flooded with anxiety. In Allison’s case, her mother insisted on helping to fix Allison’s hair or to help her clean her bedroom. Allison agreed to these things when there was a special occasion and when visitors were staying at the house thinking that she could cope with these tasks, but that night she fell apart, largely because she felt that she was contaminated and she wished to punish herself. Her anxiety soared to over 90 and how she coped was by scratching her arms and legs with a sharp paper clip. We scaled back tasks on the hierarchy to ones that she felt better able to do.

Engaging in homework assignments between therapy sessions is very important to decrease the negative thinking and compulsive behaviors. This requires practicing the feared behavior daily. What is practiced will depend on the nature of the problem. For example, Gary had morbid thoughts to harm himself and others with knives. He had to practice tasks, such as carrying a rock in his pocket during the school day, looking at the knife block in the kitchen, and using knives for cooking tasks. Eventually he practiced holding a knife while eating next to a family member without thinking about harming himself or others.

In addition to practicing exposure to the obsessive thoughts and actions, the child needs to learn how to stop themselves from engaging in the compulsive rituals. There are a number of ways that a child can learn to inhibit nonproductive rituals. It is useful to assure the client that they don’t have to stop all of their behaviors at once. At first, the client will reduce certain behaviors. For instance, Wendy carried antibacterial wipes in her backpack and felt compelled to wipe any table top surface and door knob before touching it. Throughout the day she was constantly washing her hands with these wipes. She went through several boxes per day of the handi-wipes. We decided to whittle down the number of boxes of wipes that she was permitted to use each day rather than specifying what she could or could not clean.

It is often useful for some clients to keep a chart of how well they are doing so that they see incremental improvement in their behavior. If they can see that they are reducing the number of times that they do a ritualistic behavior week by week, they will have a sense of accomplishment. This self-monitoring can be very time consuming. Overall, the client should spend a total of 1–2 hours a day on exposure to diminish the OCD behaviors.

5.2. Changing negative self-talk to positive thinking

For the child with OCD, they are often riddled with negative self-talk and self-doubt. It is very important to change how they think about themselves. Positive-Self Talk (see Skill Sheet #6) helps the child change the irrational internal voice. For example, Leslie obsessively organized her clothes and jewelry before going to bed each night. She needed to use positive self-talk to not only talk herself out of doing obsessive organizing, but to feel that she was still a good child if there was some mess in her bedroom. Or in the case of Wendy, she was very upset that she may have poisoned herself because her hands were dirty and covered in germs when she touched the bathroom door at a public restaurant. In order to refute her fears, we came up with things that she could say to herself. An example of this might be: “I have washed my hands when I finished using the toilet and there are no germs on them. My body can handle a few germs when I touch the bathroom door as I leave. I can always wash my hands again later.”

Here are a few more examples of positive self-talk.

| Irrational thoughts | Positive self-talk |

| I have not prayed enough and therefore God will punish me and my family by creating illness in me or them. | I pray to appreciate the beauty of life and what God has done for me and my family. A loving God would not punish me by creating illness in me or my family. |

| I did not have time to finish the homework I had today and my teacher will think that I am not smart. I could get a low grade. | I know that I am a hard worker. If I make a mistake or I run out of time to finish something, I can take care of it tomorrow or let my teacher know that I will finish it soon. It is not a big deal. |

| If I do not touch the mirror three times, someone will break into my house and hurt me and my dogs. | My house is secure and safe. My dogs will bark if someone comes to the door. A burglar will not come if I don’t touch the mirror. |

| I must look perfect and weigh only 80 pounds. If I don’t check my weight constantly, I will not look “just right” and I can’t stand that. | No one is perfect and no one will know if I weigh 80, 85, or 90. My brain makes me think these thoughts and they are not true. I need to practice being imperfect for a change. |

Some people find it helpful to use positive visual imagery as they engage in positive self-talk. For instance, when Gary had urges to harm himself or others with knives, he visualized the knives in a vault that he couldn’t touch and a flashing red light telling him he needed to stop himself.

5.3. Challenge faulty thinking

Faulty beliefs about danger and harm often underlie the fear and anxiety in OCD. Frequently the irrational thinking relates to the child’s tendency to overestimate the risk or danger. They may have a tendency to think in black-and-white terms or link things that don’t relate to one another. Many children with OCD are riddled with catastrophic “what if” thinking and are in a constant state of self-doubt. Others engage in superstitious thinking about their rituals or the value of certain numbers. And underlying many of these faulty thinking patterns lay the fact that most children with OCD cannot stand the level of anxiety they feel when they have these thoughts, then feel compelled to do something to minimize their anxiety or rid themselves of these thoughts.

To get to the bottom of the faulty thinking, the therapist should guide the client to understand what events activate the anxiety. It may be seeing a piece of trash on their front walk or looking at a “germy” bathroom knob in a public restroom. Next the child should identify the irrational thought that accompanies the activating event. For instance, the child may think that if they don’t pull enough hairs from their scalp, they won’t look perfect enough and people will tease them. Next, the child should determine what kind of faulty belief they hold. Is it persistent doubting, a tendency to take on too many activities, clubs, or projects, a high need for control and perfectionism, overestimating the risk of danger or harm, constant “what if?” thinking, attributing faulty cause and effect, or superstitious or magical thinking?

Cognitive restructuring is the next step in this process (see Skill Sheet #12: Changing how you think). The child develops a list of realistic ways to cope with the situation through self-talk and actions. In addition to constructing positive self-talk as detailed earlier, the child should challenge their faulty thinking. For instance, the child may try to analyze all the “what if’s” in their life. “What if I don’t get all A’s on my report card?” “What if I weigh more than 100 pounds?” “What if I get AIDS?” After making an extensive list and letting go of all the possibilities, the child focuses on how they will cope. It may even be learning to say “So what!” if it happens. How will they face the consequences if the worst thing actually happens to them or others? The therapist then guides the child to think through what positive and negative end result happens from their repetitive behavior and ways that they can prepare for the worst possible scenario without losing control or engaging in maladaptive behavior.

Imaginal exposure is another technique that is often helpful to children with OCD. With this method, the child thinks about uncomfortable fears and thoughts. These might be things like being kicked out of advanced classes at school for low grades, getting cancer for not hand washing enough, or going crazy if the world isn’t perfectly aligned. The child then writes out a story in the first person, describing the feared situation if they are not able to do their ritualistic behavior. After writing the script, the child may tape record their narrative and listen to it over and over until the SUDS rating lowers to 20 or less. Imaginal exposure does not seem to work with individuals who believe their obsessive thoughts are real, if the narrative evokes a very high SUDS rating, or the reverse, the narrative doesn’t seem to arouse any anxiety. This is why developing a narrative scene should be done under the supervision of a therapist.

5.4. Use of distractions to redirect compulsive actions

A very powerful tool for children with OCD is to learn ways to redirect their compulsive actions to productive behavior and positive thinking (see Skill Sheet #5: Distractions for emotion regulation). When the child has a distressing thought, they may focus on a pleasurable event that is going to happen or picture a safe place that they can be. The therapist should talk with the client about how to install a safe place in their mind. For example, in Leslie’s case, she was soothed by the image of her sitting outside on a swing in her backyard, looking at the beautiful flowers, tall trees, and blue sky.

Often thinking about a distraction is not enough and it’s better for the client to engage in doing something distracting. The best distractions are actions that a child can do to avoid the compulsive behavior. For Wendy, when she had a desire to clean germs from her hands and surfaces, she found that working with tile and grout helped her to feel calm. Gluing tiles on a surface, and wiping them clean before and after grouting was very soothing to her nervous system. Some people find it helpful to do activities that require counting to neutralize their anxiety.

5.5. Reformulating the concept of self

OCD thinking can take over a person’s identity, removing the pleasure of living. It is very important that the child remind themselves that “I am not my OCD thoughts.” They need to separate out that the OCD thoughts are meaningless and intrusive. The thoughts and behavior are not the only things that define them as a person. This helps them to start to disentangle themselves from acting on the thought and reconstructing a better sense of self. The focus should be on the child learning to take pleasure in their life and enjoying spontaneous moments. Some people benefit from engaging in art, music, or dance where there is no right or wrong way to do things. Enjoying a sense of abandonment and pleasure is often alien to the child with OCD. They should also remind themselves about who they are as a person and what makes them unique and valued by themselves and others, and how they can focus their attention on these positive attributes. Perhaps the child is a gifted writer, a great big sister, an excellent student, or has a knack for numbers. Often these traits become foreshadowed by the OCD rituals and the child loses sight of their positive attributes.

5.6. Working with the whole family to make things better

Many times the whole family suffers with the child who has OCD. The child’s anxiety and fear can be contagious and/or their compulsive rituals can create major obstacles to family functioning. It is very stressful for everyone when one child is continually on guard and suffers from unreasonable fears and rituals. Sometimes family members become extremely solicitous of the child, giving in to their habits and rituals. Other times, family members may feel that they, too, need to be perfect, but allow the child with OCD to get away with crazy behavior. It is important that the OCD way of thinking be explained to family members so that they realize it is a problem and not related to them. Or the parents and siblings may feel that the child is weird and should be avoided. Often the family members yell at the child with OCD and emotional or physical abuse can be a reality. Setting up consequences for OCD behaviors that impact or control the family is important so that the child suffering from OCD can see that their ritualistic behaviors have an impact on everyone whom they live with.

6. Common pitfalls: things to avoid

1. When working on exposure, the client should not be physically forced to do the feared behavior. It is helpful to go back to a less anxiety-producing step on the hierarchy, work on exposure at that level until the SUDS are down.

2. Some children with OCD do better with an immersion technique where they severely limit their ability to do their habit. For example, if it is excessive hand washing, they might severely restrict how much water and moist towelettes they are permitted to use. Other children do better with a ritual delay technique where they work first on delaying their ritual and shortening its duration. For example, if the child has a problem tolerating asymmetry, they may purposely try to mess up one object, such as the throw pillows on the sofa, and then try to delay straightening them for longer and longer periods of time.

3. Many children with OCD have obsessional slowness and take an extremely long time to do basic grooming tasks like showering. The real problem is their high need to do it right, performing the task in a strict order, and often counting or starting over for fear of forgetting a step. Sometimes the child is consumed with worries that they aren’t trying hard enough or that they are doing it wrong. These underlying maladaptive cognitions need to be addressed in therapy. In everyday practice, children with obsessional slowness usually do well with the use of timers to limit the amount of time that they spend on a given ritual. Often having a family member serve as a helper also aids in moving them along.

4. Family members need to stop doing behaviors that reinforce the rituals. For instance, Colbin’s OCD involved mimicking and repeating everything his parents said. Their response was to yell at him and lecture him to stop. By delivering their messages to Colbin through notes, Colbin’s mimicking behavior radically decreased. We gradually introduced short verbal interchanges with his parents and if Colbin repeated what they said, they gestured with a stop hand signal.

5. Family members should avoid being too reassuring while the client is practicing exposure therapy. Once the child is acting to avoid the obsessive thinking and maladaptive rituals, the family should reinforce to the child that he can handle this on his own.

6. Avoid criticizing or scolding the client when he slips back into his compulsive behaviors. Instead, family members should encourage him, praising him for all of his efforts, no matter how small.

7. Case example 1: facing a germy world

The following case example is the story of a mother with severe OCD whose daughter incorporated her mother’s OCD symptoms into her behavioral repertoire and became increasingly dysregulated as a result. It was very difficult to disentangle mother’s OCD from her child’s and to figure out if the child’s behavior would have manifested as OCD on its own or was created by her mother’s obsessive behavior. As a result, the treatment focused on both mother and child in a combination of parent guidance and individual psychotherapy for the child.

As a child, Franny’s life was filled with an endless series of compulsions and rituals to free herself from germs. Franny’s struggle with OCD began when she was 3 years old and was hospitalized for a raging strep infection that lasted for months. Franny remembers being in the hospital for several weeks and during that time, her mother never came to visit her. When she came home, Franny remembers that nobody hugged her or comforted her. She thinks that this is when her germ phobia began. As a child she had rituals that she did in secret—hand washing, tile tapping, counting, and worries about what was clean. She felt that her father was a dictator and very critical of her appearance and academic performance. Her mother was detached and the only child who seemed to care for Franny was a nanny who came to the house several times per week. When she went to college, the germ phobia escalated while living in the dorm. She would do things like wash the dorm toilets and sinks repeatedly with clorox bleach or scrubbing her skin until it became raw. She became so distraught that her father had her committed to an in-patient hospital thinking that Franny must have been very disturbed, possibly even a schizophrenic.

Franny finished college and then worked as a receptionist in an accounting firm. When she was 28, she married a man who traveled a great deal for work. Franny never felt an emotional connection with him. Her problems with OCD worsened considerably when she was 36 and had a baby. She wouldn’t let anybody hold Hannah for fear of germ contamination and causing the baby illness. Within a few years of Hannah’s birth, Franny’s OCD overwhelmed her. This is when Eric, her husband, left her. The house was a total mess. The entire second floor of the house was filled with boxes, shopping bags full of things, and dirty laundry. The junk was stacked up in tall heaps and covered all floor space and furniture. Both the dining and living rooms were unusable. The kitchen was under renovation and old cabinets and broken appliances were lying in the living room awaiting workmen to come, something that Franny could never seem to schedule. There were sleeping bags on a mattress in the basement and that is where Franny and Hannah slept. The dirty laundry was stacked high and often didn’t get done for months. It was a never ending process. Franny had to figure out where she and Hannah had been so that she knew how to wash the clothes properly. Her remedy was to buy new clothes when the old ones were dirty. Even opening her mail was a fiasco and took several hours each day. Franny did it by wearing rubber gloves and using kitchen tongs, taking great care that the mail didn’t have direct contact with her clothing, her hands, or the countertops. “You never know where the mail has been and who has touched it! My mail is routed through the same post office as the prison down the road.”

Franny would become completely derailed if her sister, Sarah, came to visit. Sarah was a probation officer and the idea of prisoners and what they had done had become another phobia. A visit from Sarah resulted in days of cleaning rituals, scrubbing herself and Hannah in the shower over and over again until she felt clean enough. Hannah would become very overstimulated by the lengthy showers and afterward, often hit or clawed at her mother, screaming hateful things at her. Franny also had to clean the hall rugs where Sarah had walked. After a visit from Sarah, Franny had to evaluate all the things that Sarah had touched or sat on and scrub them as well. Hannah responded by putting her dirty shoes on furniture on purpose to provoke her mother.

To top this off, Franny’s house happened to be within a few miles of the state penitentiary. Prisoners often used the Quick Mart that she had to drive by to get to Hannah’s school. The prisoners were sometimes on day release doing highway repair and clean-up. If Franny saw them, that would set off cleaning rituals. She had nightmares that prisoners were locked in her kitchen. Next thing she knew she would be a small child all alone in her dream, orbiting in outer space. The child would look back at earth and see a cave door opening. Out of it spewed dark, green lava. Then a small spritely elf would leap out of nowhere to rescue her. Whenever Franny told me about the dream, she would say, “I’m not sure who the child is—me or Hannah. Or if I am also the elf. What the dream means is that there is no sterile place left in this world. It’s all contaminated.”

As Hannah grew older, she was subjected to her mother’s phobias of trash and germs along with the constant washing rituals. It was highly disorganizing for Hannah to live with a mother with OCD, in the highly cluttered household, and with no siblings or another parent to help support her needs. Hannah began to look more and more like a child with severe ADHD and OCD by the time she was 8 years old. Hannah would bring things to her mother and inquire if it was clean and OK to touch. She also obsessed about whether she had cleaned herself enough after going to the bathroom, and began to scrub her hands until they were raw and wipe her bottom repeatedly until the toilet was clogged, going through multiple rolls of toilet paper each day. At the same time, she would do things to agitate her mother. One day Hannah lay on the pavement near where homeless people were sitting. As soon as she got in the car, she rubbed her shoes all over the back seat and when she got home, she rolled about in mom’s bed sheets. This type of behavior in Hannah would set off a cleaning frenzy in Franny. Usually Mom fell apart and screamed at Hannah for her behavior. When there were episodes of this sort, Franny began to call me and inquire what other mothers would do. Would they need to scrub the entire back seat of the car? Would they wash and rewash the clothes and bed sheets several times?

Hannah began to look more and more disturbed. Hannah thought that there were snakes in the tub and shower. She would say things to her mom like, “Hit me! Take a hard sharp thing and hurt me! Kill me!” Hannah often hurled her body against walls and furniture, and would climb all over her mother’s body, clawing at her mom’s hair and breasts and putting her feet in her face. Whenever Franny tried to walk past Hannah, Hannah would barricade the hallway and not let her pass, holding her mother hostage. Sometimes Hannah would scratch off bug bites on her skin until they bled just to see what happens. When she ate, she would spit and chew with her mouth wide open. Sometimes she would put her finger down her throat to purposely gag and vomit, then would force her mom to clean it up. By the time Hannah was 8 years old, she began saying very disturbing kinds of things. “Suppose a bad man cuts you really bad at the knees and you were bleeding all over the place.” “I want to die before you, Mom.” or ”I’m going to run in front of a truck today.” There was frequent talk about violence, death, and morbid curiosity. Her behavior became quite sexualized. She began masturbating in the shower while her mother bathed her. I asked her to stop showering with Hannah as soon as we began our work together, but despite my words of caution, it persisted in secret until it slipped out in passing during one of our sessions. Sometimes Hannah would expose her nipples or grab her mother’s crotch in public and exclaim, “I feel your penis!”

Hannah’s individual therapy sessions were filled with obsessive and disorganized themes. Either Hannah constructed long lines of blocks in elaborate patterns spanning the course of the room, all the while working diligently, but silently, or she would dump the horses out of the stable and pound them vigorously on the stable, denting the wood with their hooves, exclaiming loudly in horse braying sounds. Sometimes she would play in the doll house, creating earthquakes and tornadoes that destroyed the order, churning up the doll house furniture into a big dump heap. Again, her verbalizations were wild and chaotic with little dialogue and sound effects of banging noises. Afterward, one of the dolls might obsessively wash her hands in the bathroom sink. Another common play scenario was Hannah taking the monster, Godzilla, and surrounding him with an intricate block construction that eventually covered him from all sides. Usually Hannah spoke little about the meaning of her play, but on this occasion, she said, “Godzilla needs to be protected.” Who was the Godzilla—Hannah, her mother, or both of them?

In my parent guidance sessions with Franny, the first thing we did was to get her on suitable medication to help control her obsessions. We used many of the things described in this chapter to address her germ phobias along with parent guidance and family sessions to help both Franny and Hannah with home life. Franny often talked with me in our sessions about how she felt unsafe and unable to protect herself and her enormous self-doubt. As we delved into these underlying beliefs, she returned to the abandonment that she had sustained as a child when she had strep infection. “I believed that my parents loved me and that I was safe. When I got sick, I was put outside the family. It was a family that already had a lot of holes in it. I don’t understand why I was put out.”

“Where did you get put out to, Franny?,” I inquired.

“I am thinking about being out in the snow with my friends with me. My mom is not with me. My friends were my nannies. They liked me. But when they left, there was no one there for me.”

“Picture yourself with someone there for you. What happens now?,” I suggested.

“I am being taken care of. I like that. It is the right meal and the house is clean. This child helping me is warm and caring to me. I feel free. Emotionally free and carefree. Safe. Things are easy. I feel guilty that Hannah is not part of what I am imagining right now.”

Later in the session we talked about her OCD and this is what she said. “What bothers me with my OCD is that I feel that I have to trust someone else. Who empties the trash? I can picture myself as a child taking out the trash and my mother says, ‘Wash your hands!’ It’s easy. I don’t worry about the door knob. It’s not important. Things are clean enough. It’s like picking apples outside.”

“Picture that right now, Franny,” I said.

She closed her eyes and said, “I’m picturing the house where I grew up in and making ice cream in the backyard. You know what my mom gave me that was priceless? My love of nature. Her victory garden. She made things from fruit trees. I’m thinking about making jam with my mom. She grew all these things for us and fed us.”

That particular session ended with Franny leaving feeling that her mother must have loved her on some level. It wasn’t all about her being left in the hospital to fend for herself.

In another session, Franny talked about her worries about public trash cans. Franny obsessed about washing everything if Hannah touched a trash can. “I associate evil with it. It’s not a health issue. Contact with evil things will make me bad and I will be ostracized from everything good. Trash is what people throw away. If I touch the trash, I will become a throw away, like homeless people and prisoners. I remember once as a child I ate ‘dirty snow’ and I thought I would die.”

“What happened?,” I inquired.

“I am thinking about when I was 3 years old and had the strep infection. They did a tracheotomy on me because I was choking on my own mucus. I was never acceptable to my own parents. My mom was superficial, stiff in how she nurtured me. I think as I reflect back that I was like Hannah—an uncontrollable child. I don’t know how to keep safe from all these dangerous people in the world. That’s why I behaved that way.”

In the upcoming months, Franny yearned for a clean, quiet, and serene home environment. Whenever she and Hannah traveled for a weekend, she found a great sense of calm when they stayed in hotels. Everything was so clean and there was no clutter or piles of laundry. We had made a little headway in her hoarding compulsion in the past year but the problem was so massive, it was very overwhelming for her to get started and keep working on the problem. Much to my surprise, one day Franny showed up for a therapy session and announced, “I’ve bought a second house. It’s the solution! It’s completely empty and I can put only a few things in it.” Interestingly, it worked. Both Franny and Hannah seemed much less anxious and overwhelmed in the better home environment. I pushed Franny to go back to her cluttered house and throw things out little by little and to enlist workmen to haul junk and repair the kitchen. Instead of thinking of putting the house up for sale, she said, “I’m going to clean it up and that will be my retirement house. It’s really a beautiful house by the river. I just can’t live in it right now.”

As we moved along in our therapy, we suddenly found ourselves in the middle of the anthrax scare. Tom Brokaw, the TV anchorman, received a manila envelope filled with the deadly virus. The NBC newsroom immediately sealed off the studio, combing every inch to decontaminate the area. A congressman received a packet of the deadly white substance mixed in a letter. The entire federal building went under quarantine for fear of causing a pandemic. Mail was routed through the Brentwood Post Office. High-tech equipment screened mail to detect the deadly virus. Anyone who suspected that they had opened mail containing the deadly spores should take Cipro immediately.

In the upcoming week, I simply said to Franny, “You’re the master! You’re the pro! The Queen of Mail Openers!” We both laughed. “The news anchor people and the government officials could learn a real lesson from you. They’re telling us to don our rubber gloves and face masks when we open our mail, but would that really protect us?”

Franny smiled and replied, “If you really had anthrax spilling out of an envelope, it’d spread quickly onto your clothes and counter tops. There would be no stopping the germs from spewing all over the place.”

So what was my motive in asking Franny about her mail opening practices? Was it self-protection? Or was it a wish to get to the bottom of her obsession? Perhaps both. I said, “Franny, I know we’re joking about your germ problem, but perhaps I can take this opportunity to understand what it’s like for you. Tell me how you open your mail and I’ll try it out in the privacy of my own home. Next week we’ll figure out what’s next to help you and Hannah.”

The next day I thought, “I have a free hour. I’ll do Franny’s mail opening method.” I put on my apron. I would need to wash it when I finished because the mail might touch it. I set out the trash can next to the counter, carefully lined with a fresh plastic Hefty bag. I cleaned the counter top with Fantastik antibacterial spray and spread out fresh paper towels. As per Franny’s instructions, I set out the spaghetti tongs, donned my paper mask over my nose and mouth in case anthrax spores flew upward, and then put on my yellow Playtex rubber gloves. Voila! I was armed and ready!

I opened my front door dressed in my get-up. At that exact moment, a group of neighbors stood in front of my house. An innocent scene abounded. Young children in strollers, mothers gossiping together. My next door neighbor pulled up in her van and swung her trunk open to unload groceries. The minister’s wife strolled by with her Schnauzer dog in tow. Everything seemed to move in slow motion. They turned toward me with startled expressions. Caught in the act! “Ahhhh! She’s a psychologist! I guess you need to be one to know one!” Don’t give it a thought. Continue with the experiment.

I carefully extracted the mail from the mailbox with my spaghetti tongs and snuck back into the house. I noticed how hot it was under the paper mask. I set the mail down on the paper towels, then realized that I had forgotten something to use in opening the mail. It’s hard to rip open envelopes with rubber gloves on. Anything I touched would now be infected with mail germs. The drawer handle, the utensil organizer, and all the knives were contaminated as I reached inside to get a knife to open the letters. I promised Franny that I would do what she does everyday, so I would have to sterilize the entire drawer’s contents when I finished.

The catalogs were easy, but no! I recycle! I forgot to bring up paper bags for that purpose. I touched the door knob to the basement. Put that in the queue—the “to be washed” list. Next were the envelopes—slash with the kitchen knife and carefully pull out the letter contents with spaghetti tongs. Not easy with rubber gloves on. Your fingers are like sausages. Minutes tick on and now I’m at the one-hour point. My list of “to sterilize later” is growing by the minute. The phone rings and I answer it by instinct. Don’t forget to spray the receiver thoroughly with Lysol. My dogs look at me puzzled. “What’s with her!” They’re right. This is absurd, but this is what Franny does everyday. When she can’t face the mail, she let’s it stack up. That’s why the piles of mail start to mount. Doing this experiment had left me germ phobic. For days afterward I thought that whatever I touched could be contaminated. It was exhausting!

In our next session, I told her, “I have newfound respect for what you go through, Franny. I had no idea!”

She gazed down at her hands and said, “Thank you for walking in my shoes. No one has ever done that for me. They only criticize me for my clutter and the way I live my life. By the way, I brought you a Christmas present. It’s a door hanger to put over your bathroom door. I never know where to put my purse when I come here and use your bathroom. You know—germs on the floor. It’s hard to disinfect a leather purse.” I put it up just for Franny, but it was hard to shut the bathroom door.

The next week Franny called me. “I need a reality test.”

“That’s what I’m here for,” I replied.

“Well, Hannah was playing in a puddle down by the Washington monument with her friends. She got in the car and her clothes and shoes rubbed all over the back seat. Do I need to shampoo the car upholstery?”

“It’s OK, Franny. I would leave it if that were me.”

The week after that there was another phone call. “Hannah was laying in her school clothes on my bed. Do I need to wash the sheets before I go to bed?”

“No, Franny. If that were me, I’d hug my daughter, talk about her day, tuck her into bed, and go to bed with a good book. Don’t wash the sheets, Franny.”

“What a relief. Thanks,” she said.

And so it went. Week after week we had reality checks. Hannah made considerable progress in her therapy and when she was 10 years old, I worked with her in a social skills group to further normalize her experiences of the world and to help her to learn better resources in interacting with others.

8. Case example 2: stuck in endless repetitions

Olivia always showed up for therapy sessions in the same outfit—Converse all-star sneakers, a baseball cap with the brim turned backward, and a loose fitting t-shirt and hoodie over blue jeans. She wore her hair pulled back in a ponytail. Olivia began therapy when she turned 11 shortly after she moved to the DC area after living on the West Coast. Her anxiety rapidly escalated as she began middle school. Olivia had a very difficult time making new friends and was devastated that she lost her only friend with the move. She thought that she might have a new friend at school, but was so awkward in knowing what to talk to her about that Olivia resorted to eating lunch with the security guard.

Olivia was an interesting girl who was athletic and enjoyed swimming and soccer. She was happiest when she could be outdoors. Olivia was an avid reader, making books her best friend since she had moved. Although Olivia’s facial expressions were fairly flat, she talked rapidly a mile a minute, leaving little space for another person to interject a comment or idea. Olivia had researched her personality type on the Internet and wondered if she might have autistic spectrum disorder because she found it so difficult to make friends. Olivia did share some of the attributes of children with ASD but if she did have it, it was certainly a mild version of the disorder. She felt that life was so much simpler when she was little before she had OCD and social problems.

When Olivia started therapy, her anxiety had become so extreme that it interfered with daily life and was noticed by peers at school. If she accidentally bumped into something, she had to touch it again to make it even. She was very conscious of her breaths, worrying that a piece of her soul was left behind in the space she was in at the time. Her breathing had to be in perfect sets of fours. When typing, she had to always backspace in fours. Olivia was especially overwhelmed in shopping malls and drug stores where there were a lot of tiles on the floor and price tags on merchandise. These things would set off her counting and tapping behavior. When she was crossing the boundary of a room, she had to step forward and backward four times. While doing these steps back and forth, Olivia’s mind was full of thoughts that the world could fall apart and she wouldn’t be safe. She also worried that she was leaving something behind in the room, then would need to go back into the classroom or space and see if she had left a pencil, a notebook, or her book. Olivia was preoccupied with worrying about “what’s next?” in her life. As a result, school was 6.5 hours of hell for her with all the changes from one class to the next, the tiles on the floor, and the noise of the crowded hallways. Small yellow rooms like her art class at school made her want to inhale constantly. If a place felt creepy to her, she would lose something and never have it again. Touching the doorknob as she left the room helped her to finish. The resource room was her only safe place because of the lovely fish tank and rocker in the room, both of which relaxed Olivia.

Although Olivia yearned for friendship, she preferred to be alone and isolated herself when she felt stressed. At the same time, she was afraid of being alone with her own thoughts. She was very aware that her mind worked differently than others. She yearned to be listened to and validated. Other kids at school didn’t like that she talked so much and so fast. When we talked about this problem, Olivia said, “The problem is that my mind swims with so many ideas.”

Olivia’s OCD was making her feel more and more depressed. She stated that inside her body, she felt like a big deflated tire with no air left inside. She felt trapped in her own mind and couldn’t take control of it. These thoughts often led her to worrying about death, wondering if she had done anything meaningful in her life. She often worried that people were conspiring against her.

Olivia was able to identify the stressors for her OCD. They were things like lots of homework, time pressures to hurry, a packed schedule of after-school activities, and when people complained about her stepping and touching behavior making them late for the next thing. I asked Olivia, “Can you dream of a place free of OCD?.” Olivia seized the idea and said, “It has lots of green grass, open space, and a few random trees. There are no power lines and no trash lying about. I would like to be in the woods and scramble on top of rocks. I would come upon a beautiful ocean or lake and finally rest.” This conversation led us to figure out safe, calm places in each of the environments that Olivia went to. She was permitted short breaks to go to the resource teacher’s room to look at the fish tank and sit in the rocker. The school also agreed to let Olivia leave her classroom 5 minutes before the class let out so that she could organize her belongings and navigate through the halls before they became crowded. This worked well at first, but because of Olivia’s stepping and touching behavior, we found that she needed a “hallway buddy” to help her move along to the next class. At first she resisted this idea, but it soon became one of her favorite things.

Due to Olivia’s racing and rattling thoughts, we had to find ways to calm her hyperexcitable brain. An image that worked well for Olivia was picturing her mind with a dimmer switch on it to dial down her overly active frontal lobe. She would visualize her mind as a computer with multiple windows open at the same time. I asked her to label the windows of her mind into categories like “school,” “sports,” or “home life” and gradually turn off channels so that she could focus on only one thing at a time. The idea of a conveyor belt of thoughts also worked well for Olivia. She would notice her thought, label it into a category (i.e., “friends” box), and then throw it into a box on the conveyor belt. These visualizations helped Olivia to still her busy mind and let go of obsessive thoughts. We practiced emptying her mind, then focusing on one thing at a time. Doing a task like coloring a mandala, listening to music, or looking at a lava lamp helped. Olivia practiced these things everyday to slow down her nervous system. She said, “I’m like a novelty junkie. If I stay off the computer, I also find that I’m less hyperstimulated.” Her awareness of her state of mind and motivation to control her racing thoughts was a good first step.

To help Olivia develop more connections with peers, I asked Olivia to visualize interactions as a series of bridges. We practiced conversations in our sessions on interesting topics so that Olivia could learn to slow down, find out what I might be thinking or feeling, and to give me a chance to respond to her in a reciprocal manner. To help her skills in making friends, I put together a social skills group of two other 12-year-old girls. This was enormously successful and a great source of comfort for Olivia to see that she could make friends in a therapeutic environment.

An important aspect of the treatment was to help Olivia develop functional habits that worked for her in transitions to replace the breathing, stepping, and tapping behaviors. Wearing bracelets and rings that she could fidget with helped to channel the anxiety she discharged through her hands. We made lists of things to check for important transitions like what she needed to remember before leaving the classroom.

We also had to tackle the negative thoughts that roiled around in Olivia’s mind. She frequently thought that she was going to be held back, that she wasn’t perfect enough, that she couldn’t succeed, and in a very low moment, that she was at the bottom of a molten magnum. I asked her to just observe these negative thoughts like she was looking at an object, to notice them, and then redirect herself to an activity that was positive like drawing with pastels.

Olivia progressed very well in therapy and after 18 months of weekly treatment, she had begun to make friends at school and could inhibit her negative self-talk and OCD habits for the most part. Spending time with her mother was also a very important part of our work together so that Olivia could feel validated and cared for. By the time Olivia was 13 years old, she had improved to the point that she could participate in after-school activities like theater and debate team, both of which helped build her friendship base and gave her opportunities to practice talking in structured ways.

9. Case example 3: compulsive checking

It was over half an hour since we had finished our session and I noticed that someone was still in the bathroom. It was a one-child bathroom and other clients were starting to line up, rapping on the door. I hoped the child in there was OK. I listened at the door and could hear the water running. I called in, “Are you OK?.”

Owen replied, “I’ll be out in a minute.”

Owen was a 15-year-old teenage boy who struggled with OCD his whole life. He was adopted as a baby at 3 days. His parents had struggled with infertility for many years and were delighted to adopt him. All Owen knew about his biological family was that his mother was a teen who gave him up for adoption. He had two younger brothers who were born by natural childbirth by his mother. His parents divorced when he was 13 years old and shortly after this, his anxiety began. Owen claimed that it wasn’t the divorce but the pressure of high school that set him off. He began to pull out his eyelashes and pluck hairs from his scalp. He developed a neck tic and had many symmetry and checking habits. By the time he entered ninth grade, he began checking his weight constantly, worrying that he had forgotten something important, and doing and redoing school work.

Owen lived at home with his mother. He was unable to cope with school life because of the magnitude of his OCD. He filled his day with innumerable checking habits which caused him to be extremely slow in doing anything from getting dressed, to taking a shower, or fixing his breakfast. Due to the protracted time it took Owen to do any everyday routine, his mother had hired a male aide who came to the house every morning to help Owen get ready for the day.

Since he developed OCD, Owen had had a number of different therapies. The strategies worked for a little while, then he would incorporate the techniques into another OCD habit. He was taking several antianxiety medications but didn’t feel that they were helping him. Owen was desperate to be unburdened of the negative thoughts and circuitous thinking in his head. “It’s sheer hell to be me. I am locked in the prison of my own mind.”

I asked, “Do you have thoughts of escaping?”

Owen replied, “It’s not what you think. I do want to escape, but I want to live my life.”

“Just checking. Like you do,” I said.

“Very funny!,” he said with a smile on his face.

Owen was very motivated for the therapy despite his past experience with therapies not changing his OCD. He began his work with me because he was interested in learning mind–body techniques that could be combined with cognitive-behavioral approaches and hoped that this might make a difference for him. He was very articulate about his psychological condition and had many insights about what derailed his ability to function in everyday activities. The irrational thoughts and fears were constant and never ending. He would set unrealistically high standards for himself, feeling that every single thing might be judged—the preciseness of his handwriting, how he pronounced words to others, how he dressed. He constantly worried that something would go wrong in everyday routines. Would the hot water run out when taking a shower? Would the shoelace tie break on him? Would he spill the food on the floor as he fixed breakfast? As a result, he needed to constantly check to see if he had finished doing whatever it was and evaluate if he had made a mistake. If he wasn’t sure, he just started over again.

He reported, “I have a tremendous fear of not finishing something. I get stuck and can’t stop repeating whatever I am doing. And if I make a list of things ‘to do’ or set a timer, I get even more agitated.”

Nothing was automatic for him. He was in a constant state of checking things—what’s on the schedule? Did he remember his homework? Was the food in the refrigerator still fresh enough to eat? His bedtime routine took forever with repeating rituals. He might start getting ready for bed around 10:30, but wouldn’t fall asleep until 1 or 2:00 a.m. because of racing thoughts. It was very painful hearing about his daily life and how consumed he was by these obsessions. When I asked Owen if there was anything that gave him pleasure, his eyes welled up and he said, “I can never be in the moment. Everything is a do-over. There is nothing in my life that I enjoy.”

He desperately wanted friends and hoped to find someone who would love him. He said, “Nobody understands what I live with. People yell at me to hurry up or they ask what is wrong with me. My brothers think I’m a nut case. Nobody wants to be around me. I have no outlet to express the emotional pain I feel day in, day out.”

Owen also obsessed about how he looked. He was painfully aware of how odd he looked without eyelashes. When I asked him about this, he covered his face with his arm and told me, “I still do it. It’s very soothing to do. It’s a mindless activity.” He was very thin from not eating due to his obsessions about what was fresh, as well as his obsessing about whether he had exercised enough that day.

Owen believed that he was not good enough and worried that he would never succeed in life. He said, “Look at me! I can’t function in everyday life. Everything is such a struggle! I’m a throw-away. That’s why I’m adopted.” He didn’t talk often about being adopted, but wondered about his birth mother. It was never talked about in his family and he felt that this topic was off-limits.

His pain was palpable. Owen lived in constant fear of making mistakes. He thought that catastrophes would happen if he didn’t engage in his rituals. He worried that people wouldn’t want to be around “a failure like him.” He lived in constant fear that something bad would happen to his mother, that she would get sick and die, and then he would be all alone, unable to care for himself. His mind was constantly scrolling to what was the worst thing that could possibly happen. He felt that he was responsible for his younger brother who was diagnosed with a heart defect in the previous year and that his father lost his job and was struggling financially.

I asked, “If you didn’t have OCD, what would your life be like?”

He replied, “I love art and during middle school I was very talented at art, even won a few awards. They thought I had great promise, especially with three-dimensional art, but I had trouble finishing my pieces because of my perfectionism. There is no future for me.”

“Owen, can you stay with the fantasy? What would you be doing now if it weren’t for OCD?”

Owen had no hobbies but liked dancing which was the one thing that seemed to soothe him. I encouraged Owen to take dance and he signed up for both tap dancing and ballet. He had no friends but participated occasionally in after-school activities. When he could manage to go, he felt a desire to have fun with the others but couldn’t feel pleasure. Owen stated, “I get so agitated, then I can’t relax once I feel the rejection.”

I inquired, “What relaxes you?”

“Nothing except for very long hot showers and occasionally going for a run.”

In Owen’s past treatment, he had tried making hierarchies of his habits in an attempt to limit them, but without success. When he had done exposure treatment, he only felt more depressed because he couldn’t face the task at hand. Thought stopping of negative thoughts had not worked for him and mindfulness exercises had limited success. Owen had worked with a metronome in tasks to help him to keep moving.

How was I going to help this boy? He was struggling in so many ways and had been to many good therapists. None of the traditional ways of treating OCD had made a difference for him. He was overwrought with anxiety and compulsive behaviors which made it impossible for him to do daily care for himself or to take care of things like fixing a meal. It seemed that his ability to solve problem and see other options was very limited. His only way to cope with stress was to engage in compulsive rituals and negative self-talk. At the core of his problem was his fear of not being good enough, being a failure, rejected, unwanted, and unloved by others. And he had very poor self-soothing other than to go for a run. He needed ways to reduce his high state of physical and emotional distress when he transitioned to a new activity, and to stop ritualistic behaviors, especially when confronted with a situational demand. Most of all, he needed to feel that someone cared about him and that he enjoyed his life.

It seemed important that Owen experience the satisfaction of actually finishing something. He also needed to find meaningful and enjoyable leisure activities. I liked that he had an interest in art, dance, and running. These were things that we could build upon. The beauty of these mediums is that they were nonverbal and might help him to shut off his internal verbal chatter and overactive mind. With dance and running, there was the rhythmic quality of the movement, which would soothe his nervous system. He could run to a finish line or final destination and in dance, he could learn a dance with a defined ending. And unless he overworked an art piece, the finished product spoke for itself.

Owen found that when he got stuck in routines, his anxiety was overwhelming. We practiced things that would set him off on purpose like fixing breakfast, sorting laundry, or checking the refrigerator for ingredients. I urged him to observe his anxiety like an objective scientist. “OK, Owen. Tell me how you’re feeling right now.”

“I have to start this over. I can’t stand this. I’m going to mess up.”

“You can stand it. Take a deep breathe. You’re not going to start over. We’re going to wait this out together. Take a break. Look at the lava lamp for 1 minute. Then we’ll continue.” I purposely spoke in short directives, like a telegram to avoid flooding him with more verbal chatter and direct him to a plan of action.

This strategy worked well for Owen whenever he became overwrought with anxiety. We tried to build a range of self-distraction techniques to break the anxiety cycle—walking up and down the stairs, looking at something move, counting backward from 20, or doing 10 repetitions of a simple exercise. When we returned to the problem, he felt better able to cope and could finish the task we were working on. It was a bit like boot camp, but Owen seemed to like that.

A common problem we ran into was that Owen was a real pro at negative self-talk. It derailed his self-esteem and ground him to a halt. “This positive self-talk seems so trite. It’s like brainwashing my brain into thinking something I don’t believe in,” he said.

“In a way it is like brainwashing your mind. If you say something positive or motivational to yourself, it makes the part of the brain light up that makes you feel pleasure instead of fear and panic. You are helping your brain to be on your side and to get through what you are doing. If you give yourself a pep talk, you’ll feel a sense of success instead of failure. Can you try it?”

We had to come up with positive self-talk scripts that worked for Owen. Things like, “I can do this. I’m good at this. I can finish. I can enjoy this.”

Owen received very little positive reinforcement from the people in his life. His mother was weary of how hard it was to live with Owen and sometimes snapped at him for being so slow and repetitive in his rituals. He liked the aide who came to help him in the morning, but Owen felt that he only came because he was paid to help him. There were a few people who greeted him warmly when he showed up at the after-school events, but they never hung out and talked with him. And his brothers rarely spent time with him. His world was very lonely. He was hungry for a warm, engaging relationship with someone. I was very fond of Owen and found that it was easy to feel an attachment with him. But he needed more social contact with others than his small world. If he could regularly attend dance classes, a runners’ group, and an art group, he might feel less loneliness and isolation.

Despite Owen’s intelligence, he lacked awareness of how his behaviors impacted other people in his life. With his mother he had developed a pattern of dependency and with other family members, he didn’t seem to register how his obsessions could trigger their anger or impatience with him. In some of our family sessions, I urged his mother to give him feedback about these things—when she was enjoying time with Owen and when his repetitive checking was wearing her down. When the latter happened, I asked her to signal Owen that she was fatigued and in 5 minutes, she would need to leave. We were careful not to create a deeper sense of abandonment. She came up with a few things to say to Owen so that they parted on a good note, things like “My TV show is calling me” or “Got to knit! See you later.” Usually interactions with his mother ended with her becoming exhausted and yelling at Owen to “Be done already! I can’t take this anymore!”

In our early work together, Owen expressed his fears of not being perfect and his worries about making a mistake. “It’s so hard for me to stay in the moment when I am doing anything. My mind jumps around constantly to other thoughts. I’m always thinking ‘what’s next?’ and ‘did I do that right?’.” As a result, Owen never experienced the pleasure of what he was currently doing. He was often in a high alert state of arousal, feeling jittery inside with an impending sense of doom. This state of arousal occurred whenever he felt that things were not done right or that he was interrupted and forced to stop one of his rituals. When this occurred, Owen believed that something terrible would happen to him. His heart rate became rapid, his eyes widened, his muscles tensed, and he felt a need to flee.