It is not unusual for a child to feel a little down now and then, especially as he nears adolescence. Life is fraught with disappointments, losses, illness, and sad events. The child might be excluded from a sports team that they had hoped to play on, a favorite pet or grandparent dies, or they are rejected by their peer group. For most children and adolescents, feeling “down” is a transient event, and as the child engages in positive activities or events, they begin to feel better. Most cases of episodic depression last between 4 and 12 months. When the negative mood persists, the child may feel overwhelmed by sadness or hopelessness. In this chapter, causes of depression will be described. Four portraits of depression will be presented: two examples of children on the autism spectrum who also have depression, the child with bipolar disorder, and an adolescent who detaches and has suicidal thoughts. Strategies for these types of depression will be presented integrating mind–body techniques to improve the biological bases for depression as well as dialectical behavioral techniques to change the child’s negative cognitions and depressed mood.

4. Four portraits of depression

In the next section, individuals who represent the three main types of depression mentioned earlier will be discussed: two children with high functioning autism with depression who are withdrawn and disengaged, one a young boy, the other an adolescent girl; a child with bipolar illness; and finally, an adolescent girl suffering from depression.

4.1. The child with depression who withdraws and disengages

Simon was a 6-year-old boy diagnosed with high functioning autism who was very withdrawn and disengaged at home and school. Simon had been participating in individual psychotherapy for about a year at the time of the session described later. Therapy sessions tended to be filled with play that was highly repetitive and ritualistic. As our work unfolded, an ongoing theme that emerged was how sad, lonely, and isolated Simon felt and an acute awareness of his diagnosis of autism. Although he preferred playing alone and resisted all forms of social contact, Simon demonstrated by his behavioral retreat that he was extremely flooded by the presence of others. Over the course of the first year of treatment, Simon showed a growing desire for closeness with others but was at an impasse about how to open his world to others without shutting down. I had to follow his lead, letting him set the play theme which was almost always about aliens going off to outer space to escape earth. The sessions described later depict how he expressed his deep sense of loneliness and sadness to me and my response in helping him to make sense of his depression.

Play Therapy Vignette:

He had such dark circles under his eyes, like an owl. He muttered under his breathe. Distracted. I say, “You brought a snack.” Simon is annoyed. “Why do you say it’s a snack?! Popcorn is my lunch.”

“I want to write a story. It’s called The Adventures of No-Name.”

“What happened to his name?”

“He used to have a name, but his name died.”

“That makes me sad. How does a child’s name die?”

“You ask too many questions. Just write the story.”

It’s a story about a boy named No-Name. He has a collection of 47 robots called Minions. The robots are his friends, each with a unique name or number. Number 102 has the best nature. Mort is the biggest and had a ravenous appetite. He adds toppings to people food like slim and metal parts. The Minions talk, think, and act like humans. They sense things only if there is total silence. Like the robots, No-Name tells others to “be quiet” so that he can sense things. I turn to Simon. “I think I understand something about you. You need things quiet like No-Name. You like a place far away from people.”

Another day. Simon is very anxious. He checks his body with the doctor’s kit. “Just watch me do this. No talking.” He listens to his heart, takes his blood pressure, and gives himself a shot. When he is done, I ask, “Is your body safe?” He turns his back to me, abruptly changing the topic. “Let’s play Bad Guys. Get out Ice Man, Razor Back, and Fire Breather. They are going to attack me.” I pick up Ice Man and say, “There you are, Simon. You can’t escape me now. Here I come to get you!” Simon flexes his arm muscles, jumps wildly in the air, then grabs Ice Man from my hand. “No, you’re not! I’m throwing you into the bottomless pit!” He opens the container that is “the pit” and hurls Ice Man into its darkness. I exclaim, “You think you can get rid of me so easy! I’ll grab at the walls and climb out!” Simon looks at me and says, “You can never get out. You will fall and fall and fall.”

“That’s terrifying! Do I scream all the way to the bottom?”

“It’s a bottomless pit! You never die. You fall for the rest of your life.”

“Have you ever felt that way? Like you’re falling in darkness?”

He pauses and looks at me. “Do you think I can get all the bad guys in the world? If I can’t, I will need to become an astronaut and leave earth forever.”

I gaze at him. “I hope that you get rid of all the bad guys. If you can’t, I’ll do my best to help you feel safe.”

Simon frequently told me about his very bad dreams. “I was swallowing gasoline at a gas station. Then I was driving a car and it got out of control.” The dreams could be very bizarre and psychotic.“There was a mouth on the wall that laughed and talked to me. Just a mouth. No person.” I cannot imagine a mind that thinks that way. On another day, he told me this dream. “There was a police woman who threw me in prison. The whole city was flooded and she thought I did it. I convinced her that I didn’t do it.” I shudder to think what it must be like to live with such disturbing and scary thoughts. I ask him, “What makes you feel safe, Simon?”

“Playing with you, reading stories, and hugs from my Mom help me.”

“Let’s play right now. It will make you feel better.”

“I have three wishes” Oh good, maybe one will be hopeful. “I want to be an animal so that I can be left alone to daydream and not do homework. I could time travel to another planet to be alone. I just want to escape from life.” How can I ever get in? His world is so far away. “And I wish I could see the world in black and white like a dog. Colors overwhelm me. I gave up on green as my favorite color. I want you to wear black and white. I decided not to eat or touch things with color. Do you think I could get glasses that would remove color?” I reply, “A black and white world would soothe you, wouldn’t it, Simon? You need less in your life—less color, fewer people, and less homework.”

He drew a picture of a heart split in two covered with dots. “My heart is shattered into a million pieces. No one is like me in this whole world. I tried to bite my mother and kill her. I don’t want to fit in. I want the world to fit me.” I calmly reply, “You have a unique and inventive mind, Simon. But it makes me sad that your heart is shattered. When we play together, I try to understand you. Maybe that will help heal your broken heart.” Simon seemed very calm.

“I have so many inventions in my head. There is a steel whale named Maybe Dick. He’s two miles long. He swallows ships that get in his way. Rollo, the Robot and I take turns steering Maybe Dick. Rollo is one of my Minions. The Navy tries to catch Maybe Dick, but they fail. If anyone tries to get on the ship, Rollo protects me. He kills everyone who approaches me.”

“Simon. What if I’m coming along in my little boat and I see you in Maybe Dick. I would wave to you and say, “There he is. It’s Simon, my friend. I’m glad to see you.” What would you do?”

“I would let you on board, but only you. Nobody else in the whole world can come in and see my life. You could stay as long as you like and visit as many times as you want.”

I think to myself, “I have entered his world and he has welcomed me in. What a wonderful gift he has given me today.”

I saw Simon for another 12 years in treatment. He struggled with major depression which was helped somewhat by medication. Because he was so easily overwhelmed by the stimulation of school coupled with his profound need to be alone and not leave the house, he was home schooled. In all those years, he never once yearned for closeness with anybody but his parents and me. When he reached 16 years of age, Simon came to therapy one day and asked me to find him a girl friend who liked video games and roller coasters, two of his main interests. Although I was not equipped to find him a girlfriend, especially one with those exact interests, I was struck by how much more animated Simon had become over time and finally deriving pleasure from being with persons other than his family. This spurred him to start participating in social meetings of other teens who were also on the spectrum. Over the years, Simon’s depression was markedly improved and people would often remark on how animated and engaging he could be.

4.2. An autistic adolescent with depression and suicidal thoughts

Gina was a 15-year-old who was diagnosed with high functioning autism and depression. We had been working together for 4 years using a variety of modalities to access her internal world. Often she could depict her emotional life best through drama or storytelling. Her depression worsened at age 15 when her beloved dog, Snowy, died from liver failure. Gina was extremely attached to Snowy and used her as her confidant and source of comfort. Below is a description of one of our sessions when we used storytelling to understand Gina’s depression.

Therapy Session:

“May I read you my story?”, she asked, glancing at me uncertainly.

“Of course you may”. I smiled at her. “I love your stories.”

“My teacher said that I would need to take some parts out when I read it to the class.”

“You can say anything in this room to me. I’ll help you figure out what other 15-year-old kids might not understand or be ready to hear.”

“My dad said that the story was disturbing and morbid, but I don’t understand why.”

“Did you ask him what he meant by it?”

“Yes. He said that the ending was creepy. I still don’t get why.”

“Why don’t you read the story to me, Gina, and we’ll talk about it?”

“OK.” She twirled her light brown hair in her fingers, then began her story.

“It’s called A Dark World.” What follows below is an adaptation of Gina’s story.

No one knows what happened that day except for me. I will tell you the truth about that day. It was the summer of 1425. Ostriches were domesticated, flowers were blooming, and everyone wore bold, beautiful colors. I was a lowly poor farmer. A man came to town to show us a machine that could catch fish. I explained that we already had one. It’s called a net. The man took out a chicken, sheathed it, and put it in a pot. For showing me this, I let him sleep in my barn. He disappeared in the morning. When I found him months later, I discovered that he had murdered my best friend. He was sent to prison, but soon escaped.

After that, nothing was the same. All the cows and horses died, streams dried up, and crops withered away. Then one day, without warning, the ground burst, an earthquake, to reveal a chasm wide and deep. All the men in the town attacked one another, killing even mothers and children. Household pets attacked their owners. The sun disappeared into the sky and everything became pitch black. I saw a light and thought the sun was returning, but I was wrong. It was fire! The sky lit up in flames. I ran to find water and shelter but there was none. Towns people were screaming in pain. Many people were either buried or burned alive. Their skin burned and peeled from their bodies. When it was over, there was nobody alive except for me.

Now you know what happened that day. Do you want to know my real feelings about that day? It was the greatest day I’ve ever known. Why do you stare at me? Do you think I am insane?

Do you know why I loved that day? It was I who made it all happen. I thrive on misery and pain. Animal and human souls are a delicious treat. Ah, you are afraid now. I am really the god of death and destruction. This is my human form. If you see me again someday, it will be the last thing you ever see. Goodbye and good luck in the insane asylum!

Gina looked up at me impassively as if she had just read the weather forecast. I asked, “What do you think your story means?”

“I have no idea.”

“How did you feel as you read it to me right now?”

“Nothing at all. It’s just a story,” she said as she shrugged her shoulders.

“It means something very important. That’s why people write stories– to give a message,” I said. I continued. “The god of death was very powerful in his evilness. He seemed to love creating a path of destruction and making others afraid of him.”

“Yes”, she smiled with an evil grin. “Wasn’t that a good ending?!”

“It took me by surprise,” I said. “At first I thought the poor worker was a victim who was afraid of being harmed. Then the story switches and you realize that he’s the evil one.”

“I loved that part!” she said as she rubbed her palms together.

“Can you imagine being both afraid and wanting to hurt others at the same time?”, I replied.

“I hurt myself sometimes when I get afraid. I hit my head and pull my hair out.”

“Yes, Gina. Sometimes you get really overwhelmed. The fear takes over. What makes you so afraid?”

“My step mother. She is pure evil. I want to kill her.”

“What’s so evil about her?”

“She makes me do things I don’t like to do.”

“Like what?”

“Shower, make the bed. It’s not normal in her house. Everything is too clean and neat.”

“And that makes you want to kill her?”

“She married my daddy. I dream of killing her with a knife. Then my mommy and daddy would be back together again.”

“It’s so sad for you that your mom and dad have divorced. I wish you could have them back together like when you were younger.”

“My step mother will probably want to put me away when she knows I want to kill her.”

“Like in an asylum?”

She looked blankly at me. I knew that I would lose Gina if I steered the discussion in the wrong direction. I decided to normalize her response. “You know, Gina, a lot of people have very strong, even violent feelings inside and don’t know what to do with them. Is that what you’re talking about?”

“Yes, sometimes. But sometimes I feel like I’m not really here. Since Snowy, my dog, isn’t here anymore, I must not be here. It’s an odd feeling I have.”

“You’re here in this room with me right now, Gina. Feel your hands on your lap. Feel your feet on the floor. Look at me.” She did.

I continued. “You miss Snowy so much. You loved your dog. Sometimes when kids get that sad, they can’t stand how they feel and want to leave.”

“I talk to Snowy every day.”

“A lot of children speak to their pets. I wish Snowy was alive to hear your words. Your mom, dad, and I are here for you. Do you know that, Gina?”

“Yes, but I sometimes worry that everyone will die and so will I. The real me is asleep. This is me in a dream. Snowy dying was the beginning of a nightmare. I’ll live out this dream because it’s like normal life. When I die, I’ll wake up.”

“Are you afraid that when you feel this way you aren’t sane?”

“Yes. I worry that I’m really insane or that Daddy will think this about me.”

“Do you think of killing yourself so you can be with Snowy and not have this dream-like feeling anymore?”

“Yes. Suicide might work, but I wouldn’t do it because my brother would be afraid.”

“Those are frightening thoughts. Let’s glue you back together again, Gina. Right now we’re going to practice being here together in real moments. Take a deep breathe.”

I guided Gina through a mindfulness exercise to bring her into the here and now. We visualized her safe place on the beach, looking upward at the clouds, a gentle breeze blowing over our faces. We relaxed our bodies into the warm sand and listened to the ocean waves along the beach. When we opened our eyes we talked about what she would do at home to stay present in the moment. Drink a cup of cinnamon tea with her mother. Rock in the rocking chair while listening to her favorite music.

I ended the session. “Let’s try these things today and tomorrow. If you feel like you’re in a dream, write it down like a story to share with me. Your mom, dad, and I will keep you safe so that nothing bad will happen to you. Do you feel safe now, Gina?” “Yes” she said calmly and smiled. “I feel much better. See you Thursday.”

4.3. A child suffering from bipolar illness

Ziza was a 9-year-old girl with a complicated history. In addition to her learning and developmental problems of dyslexia and sensory integration disorder, she came from a family with multiple difficulties. Her father was severely depressed and suffered from alcoholism which ultimately led to the parents’ divorce when she was 5 years old. Several years later, her mother moved in with her female partner, taking all 4 children with her. The father moved away to another city and ceased all contact with the children. In addition, her mother reported that she had terrible postpartum depression after Ziza was born, her depression lasting for several years. In the family there was an 18-year-old sister, a 16-year-old brother, and a 6-year-old sister.

Ziza had considerable difficulties adjusting to the disruptions in the family, the loss of her father, and her mother’s new partner. She eventually developed a close relationship with her mother’s partner and found her to be very nurturing. Ziza, however, felt that she could barely remember her father and often looked for him on city streets. She hoped to find him and ask him if he loved her.

Ziza was a very serious, curious, intense, and spiritual child. Whenever she appeared for a session, she looked unkempt, her hair tangled, and disheveled and her clothes covered with the remains of whatever art project she had done that day. Her world was an endless stream of disorganized messes. When in an agitated fit, her favorite thing to do was to throw her comforter and pillows wildly around her bedroom, then to make her bed all over again. Her favorite thing was to hold her lucky rock in the palm of her hand.

From the very beginning of our work together, I never knew which Ziza was going to enter my door that day. There seemed to be two Zizas who came to see me.

Ziza #1—This Ziza was mute, nonverbal, and needed me to be very quiet, connecting with her through gestures and affect. She seemed to take me in as if she were sucking me through a straw. Sometimes she played silently with a pin impression toy, imprinting facial expressions like a silent scream, then staring intently at the pin mask that she had made. She wanted me to react with no words, and if I commented, there was no response. On these days, she liked to make projects, such as a diorama with small corks and clay “mushroom people” who lived on a raft by themselves. There was no story—just stillness. She sometimes became exasperated if what she made was not quite right.

Sometimes the session theme was about how her needs could never be met, that they were boundless, and that nothing I did would please her either. Her disappointment in me and what was in my treat bag was profound. It felt like the end of the world. Despite her great love for her “lucky” rock, Ziza would sometimes inadvertently toss it over her shoulder. This accidental toss of the rock would lead to a panic attack if Ziza couldn’t find her rock. Once at a shopping mall, the lucky rock fell over the balcony into the fountain below. She was devastated exclaiming, “My life sucks. All I ever do is lose things.” This same thing happened in my office multiple times—her tossing something over her shoulder that was meaningful to her play. Once she tossed a key character from the sand story over her shoulder in this way, and mysteriously it was never found.

On days that Ziza was predominantly silent, the mood was one of deep sadness, abandonment, aloneness, emptiness, and unbearable disappointments. On one such day she was working in sculpey clay and said, “Nothing makes me happy these days.” At the end of that session, she became quite animated, telling me about a booby trap that she had constructed, placing a cup of pee over the door that fell on Tommy, the evil neighbor boy.

An event happened in the fall that sent Ziza into an even deeper depression. Her older sister, Jamie, was living at home with her boyfriend as she prepared to have her baby. The baby died of a serious infection within a few days. Ziza screamed when she heard the news. Soon after this event, Ziza came in and spent the session trying to make something out of wood shapes over and over until it evolved into a little rod with moving rings on it, much like a baby rattle. Ziza was listless and sad about the baby dying. As she held the rattle, she stated, “This will help me with my worries.”

Each session ended with Ziza giving me a big bear hug as she left, expressing that she wanted to spend lots of time with me. As I struggled to make sense of what her sessions meant, I felt that she was showing me the emptiness she had inside and her lack of an inner voice. Her dyslexia and sensory problems confounded her difficulty in constructing a sense of self. Ziza seemed to be a magnet for sadness, abandonment, and loss which she continually reenacted with the loss of her favorite transitional objects.

Ziza#2—Then there was the other Ziza who came to see me. This Ziza made elaborate stories in my sand table. She would meticulously place props in the sand in exact locations, then enact an elaborate story, narrating the whole time. These stories were about “Hyper Boy” who looked much like a little devil. Hyper Boy would usually destroy the entire town, knocking things over, and blowing things up in any way he could. The baby in the story would get peed and pooped on, then ultimately buried in the sand. This particular story line happened before her sister’s baby had died. People would gather around to witness this event but nobody seemed to care what had happened to the baby.

In another story, Hyper Boy looked for sea creatures, then peed and pooped in a fenced area while creatures lined up to watch the performance. Ziza seemed to get tremendous relief from expressing these stories filled with such primitive emotions. It seemed impossible for the other characters to take care of Hyper Boy or to contain his impulses because he was so destructive and hyper. Sometimes at the end of her story, Hyper Boy would go to the Magical Toilet which would suddenly transform him into a very calm child. But lo and behold, the townspeople would suddenly become the ones who were hyper. I worried that Ziza only felt pleasure when she was hyper or in a manic state.

When she played these stories, they were very disjointed and hard to make sense of. Despite the disorganization, a recurring theme was that the characters, whomever they might be—an astronaut, a king, a hobo, or Hyper Boy, were not allowed to use the magical moon toilet to relieve themselves or else they would die. The world would become dark with no light and bad things kept happening, like the hobo’s brain would turn into mush.

So what did these two Zizas mean? Here was a 9-year-old girl who had had a tumultuous family with multiple losses and disruptions of attachment figures. Her developmental and sensory problems impinged on her ability to make sense of her world. She struggled every day with how to tolerate frustrations and disappointments without falling apart. As I worked with her mother and her partner, we put in place nurturing activities, daily structure, and dependable routines that centered Ziza. We worked on handling minor disappointments like what to do if they ran out of something they needed for a project. Because Ziza had a gift for losing the important things in her life, we set up an organizational system for her belongings and helped her to keep track of these things. We also worked on establishing a safe, quiet, calm-down zone at home for her where she could go when she felt overstimulated and hyper inside.

Although it took quite some time before there was more consistency in mood and less oscillation between Ziza #1 and Ziza #2, gradually Ziza learned to speak about what she was thinking or feeling. I urged her to use a search light in her mind to find the thought, to pinpoint what troubled her and to find a way to express it or to soothe herself with an appropriate activity. Gradually her stories became less primitive and began to have a story line that focused on making connections with others and experiences and people who were more regulated and calm.

4.4. A teenaged girl suffering from depression

The first sign that something was awry when Sonia started doing things like going out to the city park with her girlfriends, dressed as a homeless person, and drinking cider out of a paper bag. It was around this time that Sonia’s best friend tried to commit suicide and was hospitalized. Shortly after this Sonia called a meeting with her parents and told them that she needed help—either a therapist or medication.

Sonia expressed how she felt like an outlier for many years. She was a 15-year-old girl of Indian-Turkish descent and felt that she didn’t fit in culturally with the teens at her high school even though it was a fairly diverse population. Sonia also felt singled out because she began puberty early at 8 years of age. Sonia was an intelligent, talented, outgoing, and gregarious young lady who made straight A’s in accelerated classes, but for the first time, she had to put effort into her studies. She had a beautiful voice and loved singing in school musicals, but often didn’t get picked for the cast which was enormously disappointing for her. She blamed this rejection on her racial-ethnic background.

Sometime at the beginning of her sophomore year, Sonia’s mood began to change. She oscillated from a positive mood to feeling depressed, sometimes crying uncontrollably, to the point of being inconsolable. The bad moods affected her sleep which had been disordered since infancy. Sonia presented as a coy, theatrical young lady with dramatic, but pretty facial features and a shock of dark shoulder length curly hair. She had a well-developed but heavy set figure. During our sessions, Sonia would often gesture in a dramatic manner, then would look carefully at me to see her effect on me. Despite this quality, Sonia was genuine and forthcoming from the beginning of therapy. She described herself as often feeling sad, losing pleasure in her life.

An incident that seemed to have a great impact on Sonia was the death of her grandmother who died several years earlier in the family’s living room. Her grandmother had lung cancer and declined over the years. At the end of her grandmother’s life, she lived in a hospital bed in the family’s living room. Nurses came to the house and near the end, she was comatose. Her grandmother died in her sleep and was taken away before Sonia woke up the next morning. Sonia felt shocked by this. Initially she felt no reaction, but several months later, Sonia found herself sobbing uncontrollably.

Sonia also struggled with a conflictual relationship with her mother, feeling that her mother often acted angry at her. Sonia felt that a great source of tension for herself and her mother was that her mother had to deal with a life of unfulfilled dreams, serving her parents who both had prolonged and painful illnesses. On the one hand, her mother wished for Sonia to have a fulfilling life, but her mother seemed envious that Sonia didn’t have the same struggles that she had had.

Sonia’s depression felt like a blanket over her emotions. She felt empty, thinking that she would never be happy and she felt uncertain about her future. She hated being a teen and being told what to do. She had thoughts of cutting herself, but she hadn’t harmed herself yet. Often she would lay on her bed for long periods of time, surfing the internet to figure out ways to commit suicide. She thought an overdose of Tylenol might work.

Sonia described her family as one loaded with nonverbal buried distress. She worried that her parents might get a divorce since her parents fought constantly, shooting hostile looks at one another, or isolating from one another. Her mother had long-standing issues with depression and her grandmother had bipolar mood disorder.

As we began therapy, Sonia often talked about how she couldn’t rely on who she was. Sonia didn’t know if she would feel precocious or shy. I suggested that she might be a combination of slow-to-warm up and extravert depending upon the situation and her internal stress level. Sonia felt troubled that she never felt like her true self with peers. Often she thought, “Who am I really?” When she was buoyant and exuberant, she felt that she was just acting. I asked her to journal notes to track when she felt most present in the moment and content with herself.

When she returned the following week with her journal, Sonia reported that she felt happiest when she was writing, singing, or acting. Yet at the same time, she was constantly plagued with the need to be perfect. She walked and talked early and was often told by her parents that she was very intelligent and talented. However, at her high school, she felt that her peers treated her with condescension. In middle school she frequently questioned, “Am I smart? Am I pretty?” Now that she felt displaced by peers who were better than her at things, she felt diminished. A major blow for her was not being picked for the school play several years in a row.

I asked Sonia to think about connecting to present moments, especially if she felt detached or not feeling like herself. What made her feel present most was talking to her friends, doodling, hand wringing so that she could feel the bones in her hands, wearing rings or bracelets to fidget with, chewing ice or gum, eating crunchy carrots, and singing hipster songs. Whenever she felt not herself, I asked her to try on a mantra like, “I’m just acting right now. That’s OK.”

The next week, Sonia wrote in her journal the following excerpt. “I hate who I am on these kinds of days. Some days I feel empty, like there’s a chasm opening inside me that’s splitting me in two. But today I just feel heavy. Trapped. Like every inch of air pressing in around me becomes heavy and weighs on my shoulder. Every small annoyance seems magnified and I hate it. I hate everyone else, I hate myself, and I’m terrified it shows. I just want to be alone, and I want to get away. Not just from everything outside, but from myself, and everything about me that is wrong and doesn’t fit into who and where I am. I want to curl up and cover my ears so I can’t hear myself when I start thinking about how these parts of me, and these feelings and thoughts, mean I will never be happy; never by okay with being myself. My skin feels fake and I want to take it off.”

A few weeks later, Sonia had a moment of feeling very detached when she went to a restaurant. She went to the ladies room and saw multiple images of herself in the infinite progression mirrors. She felt that it triggered a sense of disembodiment and she thought, “I don’t recognize myself. That’s not me.” I inquired, “What is your ideal ‘Sonia’?” She replied, “Feeling put together, losing weight, doing something with my body.” She loved it when she felt both mentally and physically balanced, especially having a mental challenge, running 3 miles, or wearing something nice. When she did Tae kwon do, she would get in a flow and felt good. She felt bad when she was lazy and would think, “I should have done more.” Sonia held within her a strong sense of “I’m not good enough.” Her parents pressured her because they viewed her as smarter and more talented than others and she should be more productive.

We talked about the mirror incident and what was triggered for her. She stated, “It was my eyes seeing myself”. I urged her to take in through her eyes what pleased her and avoid what she didn’t like. She stated that she hated visual clutter. I suggested that she might sit by a wall to avoid seeing visual chaos in busy environments. She said that she wanted an extra ear piercing and wanted to dye her hair black and look like a pirate. She felt that by doing so, others would see her with their eyes in a different way.

The next session, Sonia brought in a poem that she wrote late into the night.

Sonia’ Poem—

She has curves and edges.

She smiles, but it is sad and strained.

If she laughs, she is beautiful.

Her eyes bore into you.

You can’t look away.

When I asked Sonia what the poem meant, she said, “It’s more about my reflection than the real me.” She desired to be alone and felt trapped by her mother and living with her family. She said, “If only people knew who I really am...” I asked, “What would they find out?” “I’m not dumb and shallow. I act like an air head and act clumsy, but there’s a very serious part inside of me.” I inquired, “When are you really you?” She replied that she is more real and honest with her friends. She wanted to be more secure in herself and be better at budgeting her time, avoiding all the procrastination she did. This led to a discussion of the tug of war that she felt inside herself, between the extravert and social child that she was and the side of her that wanted to be alone and isolated. She wanted to feel a stronger sense of self. I asked her to write down when she felt “the most you and most connected to herself.” What was she doing, thinking, and feeling?

Sonia came the next week talking about how she yearned for her mother to understand how she really felt. She constantly felt dismissed by her mother. If Sonia said she was depressed to her mom, her mother would reply that she was also depressed and minimized Sonia’s feelings. Sonia wanted to say to her mother that her experiences were different from hers. Sonia wanted time for herself when she could relax, not stolen time but a time when she didn’t refer to the to-do list hanging over her head. She felt that watching TV, writing poetry, and singing while she cooked were things that made her feel happy. She talked about the notion of time, near point time when she rushed through things and wished for future time. I urged her not to fast-forward her life to the future moment and to live for herself now.

In the upcoming sessions, Sonia talked a lot about the conflict she felt with her mother. Each had their own strong opinions and mom was constantly correcting Sonia. Sonia felt that her mother wouldn’t let her have a mind of her own. If Sonia wanted to dye her hair black, shave her head, or do an extra ear piercing, her mother objected. If Sonia said that she was attracted to girls, her mother said, “You don’t know what you really are.” Sonia felt that she was attracted to both genders, whoever was “hot.” We talked about how Sonia would like her mother to listen to her and not dismiss her. There was a lot of yelling between the two of them which caused Sonia to shut down. Her mother was emotionally reactive and took things personally. Arguments always ended with mother knowing best and Sonia feeling that her opinions were unwelcomed. Sonia felt ignored and dismissed by her mother. She wanted a more reciprocal conversation with her mother without people getting upset. If mom saw things her way, Sonia felt that she would learn to become a better decision maker and to be more independent.

I suggested that we have a conversation with her mother in one of our upcoming sessions. Sonia became very anxious, thinking her mom would yell at her. To neutralize the idea, I asked what she liked about her mom. Sonia said, “She’s fun to be around, has a lot of interests, and she wants what is best for me.” The problem was that Sonia felt that she had to live mother’s dream.

I prepared Sonia for our session with her mother. I asked, “What do you want mom to know about you and what would be a good outcome?” Sonia felt that she would like to have her mother understand how depressed she felt. I used a technique from dialectical behavioral therapy to work on effective communication between the two of them, but to also offer Sonia structure on how to talk with her mom (see Skill Sheet #20: Communicating effectively with others). Here is what we came up with:

“Mom—you are a big supporter of me and you advocate for my future. I am struggling with depression and don’t know who I am or who I will become. I feel unmotivated to put out a full effort in school work. To help me become more independent and be better at making decisions, it would be good if I could share more with you what is on my mind.”

As soon as we began the session, Sonia’s mother launched into a litany about her own needs, how she had never been validated in her own life, and she had to live to serve her own mother. Sonia’s mother felt that she had never actualized who she wanted to become. Instead of it being a session for Sonia’s needs to be heard, it became all about Mom’s lack of validation. She talked about what a horrible time she had getting over her mother’s death and needed therapy for situational depression. She also felt that all her life she suffered from racial prejudice. I allowed Sonia’s mother the space to talk about these things and validated her distress, but then tied it back to her daughter, highlighting how her daughter felt in some ways much like her. Something must have shifted as the session ended, Sonia asked her mother if she could do something positive for her appearance that would be uplifting. Her mother agreed to let Sonia color her hair. That weekend Sonia dyed her hair purple and was elated with the result.

I noticed in the upcoming sessions that Sonia and her mother seemed to be enjoying one another in a new way. I would often come out to the waiting room and find the two of them laughing together in an intimate way. Our sessions shifted to talking about how Sonia felt that she couldn’t control the rattle in her brain. We focused on ways for her to still her mind. She liked the image of washing her thoughts away with an image of a waterfall or that she could shrink down a thought into the sunset, exiting it out a window while taking a deep breath.

Sonia’s depression dramatically improved through our use of a variety of techniques—gaining insight, using mind–body techniques to focus on stilling the body and mind, building a more integrated image of her internal self, finding pleasurable and fulfilling activities, and learning how to communicate better with her mother for a better relationship. Instead of Sonia being stuck in a place of unmet dreams and not belonging, she found that she could build a different internal narrative about herself that transformed her depression to a positive mood and view of herself.

5. Effective treatments for children suffering from depression

5.1. Validation, accepting one’s reality, and learning to tolerate distress

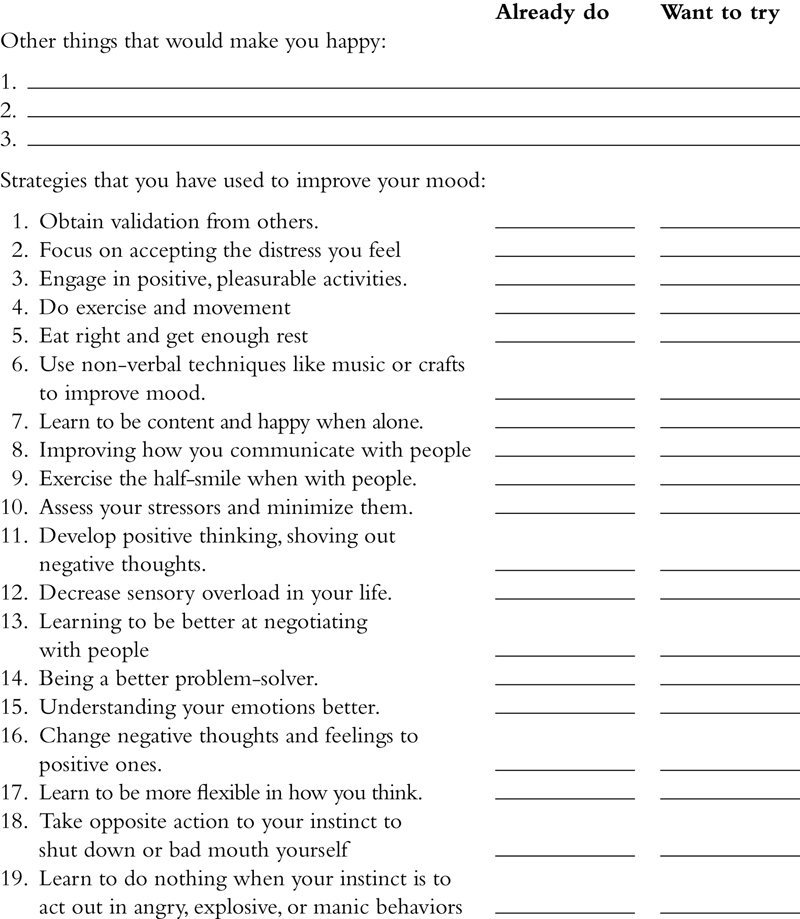

The first and most important intervention for any child suffering from depression is validation. The child needs to feel that they are listened to and understood. Often the first step in therapy is to hear the child’s story, to bring their conflict to consciousness, and to better understand the depths of their distress and the conflicts that they experience. An important part of validation is to help the child understand how they think and feel and what drives the depressive thoughts and feelings. This requires an investigative mind and capacity to pull apart the conflict underlying the depression. Often in depression, the conflict relates to activity versus passivity. The child may be fearful of being judged by others, then he resorts to doing nothing and isolating himself from others to avoid situations that may cause him to be ridiculed. Or the child has become inert, feeling hopeless, and that life is futile. He may sleep for long periods of the day, unable to motivate himself to do anything, watching TV without even knowing what he has watched. In these examples, it is helpful to highlight when the child is active and passive, the benefits of each of these states for the child’s goals, and how the child’s mood drives these behaviors (see Skill Sheets #9: Validation and #12: Thinking with a clear mind).

The dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) approach (

Linehan, 1993) is very useful in understanding how these conflicts play out dynamically in the child’s life and steer the child’s mood. The dialectic approach asks the child to look at the two sides or contradictory positions of a feeling. In depression, it is commonly hopelessness versus hopefulness. These two opposites are in fact related to one another and one must think of how to move from one position to another depending upon the demands of the situation, the child’s state of being, and the choices available in the moment. The depressed child often feels paralyzed and unable to move from the position of hopelessness and may feel stuck in that place. The DBT approach helps the child to identify what choices are available to them. By remaining immobile and passive, the child is choosing that position. What are the consequences for the child if they make that choice? And how can they consciously take charge of their inactivity for a healthier adaptation?

An important aspect of validation is accepting the reality of existing distresses in the child’s life. It may not be possible to change events for the better, in which case, the child needs to tolerate his state of distress and learn to live with it. Exercises that focus on observing breath and seeking calm-down spaces are very powerful in helping the child manage their state of distress. Deep breathing exercises described in the Skill Sheets #7: Mindfulness: Stilling the mind and #8: Systematic relaxation: Stilling the body. One may also do deep breathing and counting steps while walking, counting breaths while sitting or lying down, and observing breath or doing a routine activity, such as listening to music, petting the dog, or walking in the woods.

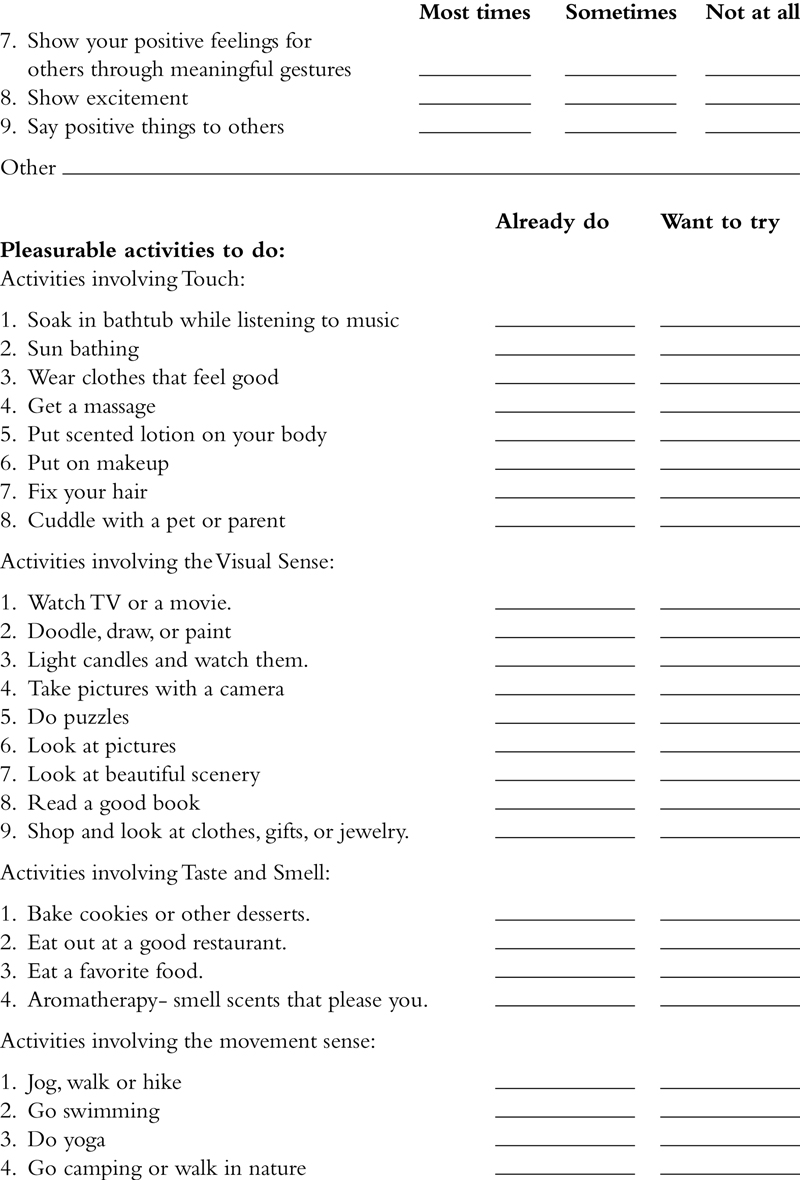

5.2. Experiencing positive, pleasurable activities

When a child is depressed, they become immobile and unable to experience pleasure. It is very important to begin with small behavioral changes and help the child to start seeking active in positive, pleasurable activities rather than withdrawing. By engaging in pleasurable activities, the child can activate the reward-centers of the brain and increase endorphins which elevate mood. Finding activities that are interesting or novel will help the child to distract themselves from whatever is bothering them. These activities also serve to build self-esteem and a sense of competence (see Skill Sheets #11: Creating positive life experiences and #16: Keeping track of positive behaviors).

The first step in treatment is to activate the child to seek pleasurable activities. Often taking the first step is overwhelming for them, so it is helpful to begin with small moments of pleasure. Using mindfulness therapy techniques, the therapist can help the client select something that might give them pleasure—looking at a beautiful flower or picture, sipping on a cup of tea, rocking in a chair, or listening to music. The therapist may wish to practice taking in positive experiences with the child—enjoying the sound, the touch, the sights, the scent, or the movement in the moment. Often the child is so depressed they can’t initiate these pleasurable moments and they need help to get started and in learning to process pleasure again. All negative thoughts need to be dismissed and pleasant thoughts optimized.

5.3. Introduce exercise and movement

Many children who are depressed and withdrawn become inert, don’t move, and as a result, do not stimulate their vestibular system which processes movement, increases arousal states, and is important for maintenance of muscle tone and posture. By moving and exercising, mood becomes elevated. If the child is depleted of energy, they may begin introducing movement by simply sitting on a rocking chair or a swing. Engaging in physical activity, such as a sport, yoga, dancing, or bike riding is ultimately more effective because the body is physically active. By stimulating the movement receptors in the body and brain, mood improves as a result of elevating arousal levels (see Skill Sheet #3: Moving for mood regulation and sleep).

5.4. Use nonverbal techniques to improve mood

Working nonverbally with a child can be a very powerful modality to get in touch with somatic responses associated with depression. Use of music, art, and dance are especially powerful in installing a sense of emotional well-being. Music with strong rhythms and a deep bass or interesting melody can change a child’s emotional state. Art projects with lots of color and texture, such as working with clay, fiber arts, beading, painting, or woodworking evoke emotional expression and release. When working nonverbally, it is often helpful to enjoy the quietness of the activity. Once this has been experienced, the therapist can bridge the nonverbal with verbal mediation, helping the child to understand the somatic responses that accompany the nonverbal activities. Noticing the effect these activities have on the body and mind is very powerful—how the muscles relax, the breathing is deeper, and the heart rate is slower. A sense of peace and calm should accompany these activities that go with a feeling of well-being. The therapist should help the client to observe these states of being much like a mother might observe and notice her young baby as he explores an object in his hands, taking pleasure in her baby’s own sense of discovery. Developing a sense of observing ego is very powerful in the healing process. The use of nonverbal medium often helps the child turn off the excessive verbal chatter or distracting thoughts in the head, allowing space for positive self-reflection and pleasure.

Introduce opportunities for touch and physical contact in nurturing ways into the child’s life. Often children who are depressed withdraw from physical touch, secluding themselves, thus causing their nervous systems to become more brittle and isolated. Tactile contact is extremely soothing and can be introduced in many ways—hugging the family pet, cuddling with a sibling or parent, getting a back rub from a family member, or going for a massage. If the child has few opportunities for touch in daily life, they should find ways to provide self-touch through contact against surfaces, such as doing yoga poses that provide high contact on the ground. Using a loofah sponge on the body while bathing, or soaking in a bubble bath are some other examples.

The olfactory sense is also very powerful as a relaxant. Lavendar, cinnamon, geranium, and other flower scents can have profound relaxation value to children who are depressed or anxious. If the child needs activation, peppermint scents can be arousing.

5.5. Learning how to be content and happy when alone

Children who are depressed sometimes feel better when in a stimulating, busy environment, especially when surrounded by happy, energetic people. The reality is that some children feel that they can’t mobilize their energy to leave the house for these types of activities. Being content alone may be a good first place to focus. The child may be easily overwhelmed by stimulating environments, especially if they have been secluding themselves at home. It is not uncommon for a child who is depressed to induce a state of sensory deprivation by their own isolation. A solitary activity that gives them pleasure and provides sensory stimulation may be a good place to start. Craft projects, reading, playing a musical instrument, or cooking may help the child to lift their mood.

5.6. Developing Social Connections

Many times children who are depressed become isolated from others which compound their sense of loneliness and rejection. Finding structured activities that ensure interactions with others on a regular basis is important. Participating in a social skills group, a scout troop, sports or dance team, or art class provide structured activities that are organizing. Simply going to the playground or walking the dog in places where people gather may be a good first step if the child feels they can’t initiate conversations with others. If the child resists leaving the house, it may be wise to arrange for someone he loves to visit regularly. The focus needs to be on going to positive places that give the child pleasure and being around people who make them feel happy. The child should seek out people who are positive and provide them with an uplifting attitude about their life. It is important to minimize contact with people who are down or negative as much as possible.

A simple but very powerful exercise for depressed individuals is instituting a half-smile and standing and moving with an uplifted body posture. The sad facial expression and stooped body posture common to depression often turns people off, causing them to avoid social contact with the depressed child. When going out in the world or interacting with family members, the child should be conscious of emoting a half-smile and lifting the neck and shoulders into an uplifted body posture. A pleasant looking face begets smiles and welcoming gestures from others. The half-smile and uplifted body posture also provide a biofeedback loop within the body and brain, stimulating the hypothalamus and hippocampus to feel more positive energy in the face and body. This feedback loop helps the child to feel more positive, even if they don’t experience it on a cognitive level. The child should practice half-smile and a lifted body posture when doing simple chores or activities, going to school, or interacting with a stranger or friend.

5.7. Assess stressors that depress the child

Making changes in the child’s daily schedule is important so that there are varied, pleasurable activities throughout the day coordinated with organizing rituals (e.g., mealtimes, bathing, recreation, exercise, baking, school work, etc.). It is useful to identify activities or environmental factors that might have a negative impact on the child’s mood. Here are a few guidelines:

• Eating: Does the child snack constantly throughout the day or fast for long periods in the day which may contribute to a drop in blood sugar, thus making the child more irritable and depressed?

• Sleeping: How much sleep is the child getting? Is it too much or not enough?

• Sensory Stimulation: Is the child getting enough stimulation throughout his day or is he overwhelmed? Should there be more or fewer activities throughout the day?

• Exercise: Does the child exercise and move?

• Environment: Is the household frenetic and overwhelming or is there calm and comforting family time? Does the family gather for mealtime and are these times for closeness or chaos? Is the home and school environment conducive to improving mood? A dark, cluttered, chaotic home or school situation can make a child feel depressed.

• Relationships: How do the family members connect and interact and is it pleasurable? Is the child subjected to other people in his life, especially caregivers, that are depressed and gloomy?

• Daily routines and rhythms: It is helpful to go through daily life activities and routines and establish what is helpful and what may need changing to help elevate mood. Is the day frenetic with no scheduled breaks? Is there time for leisure activities and self-soothing?

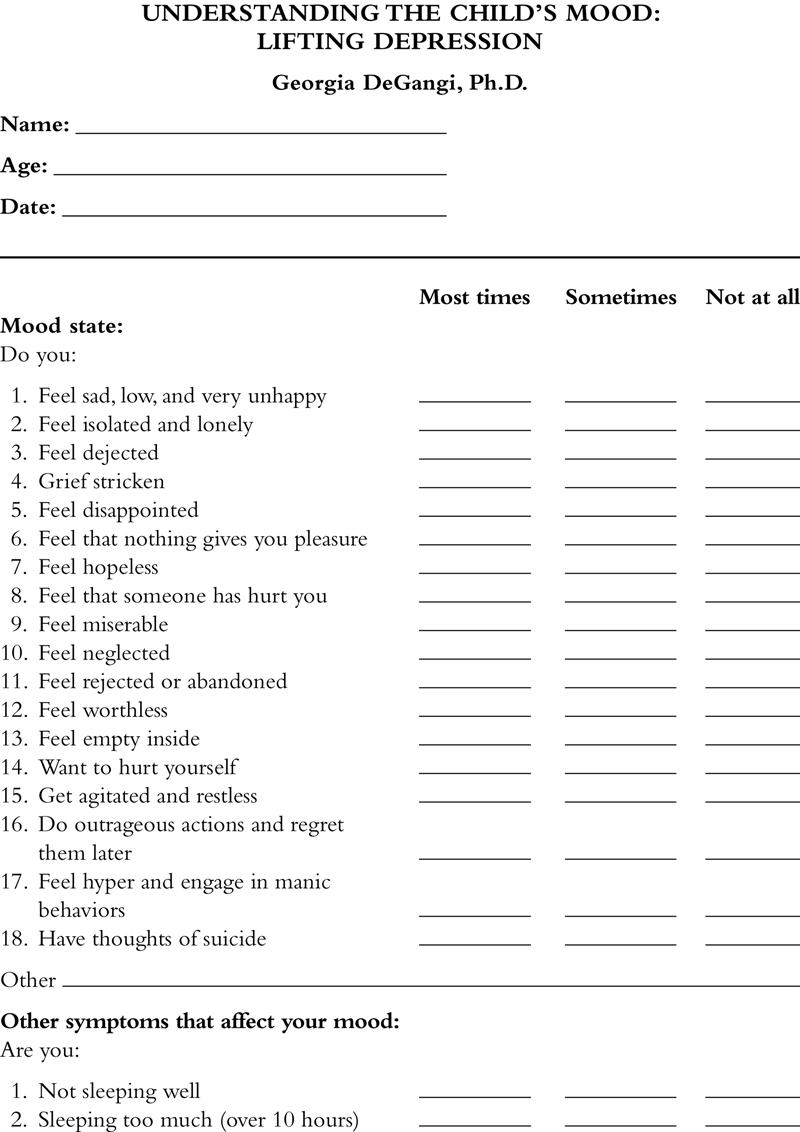

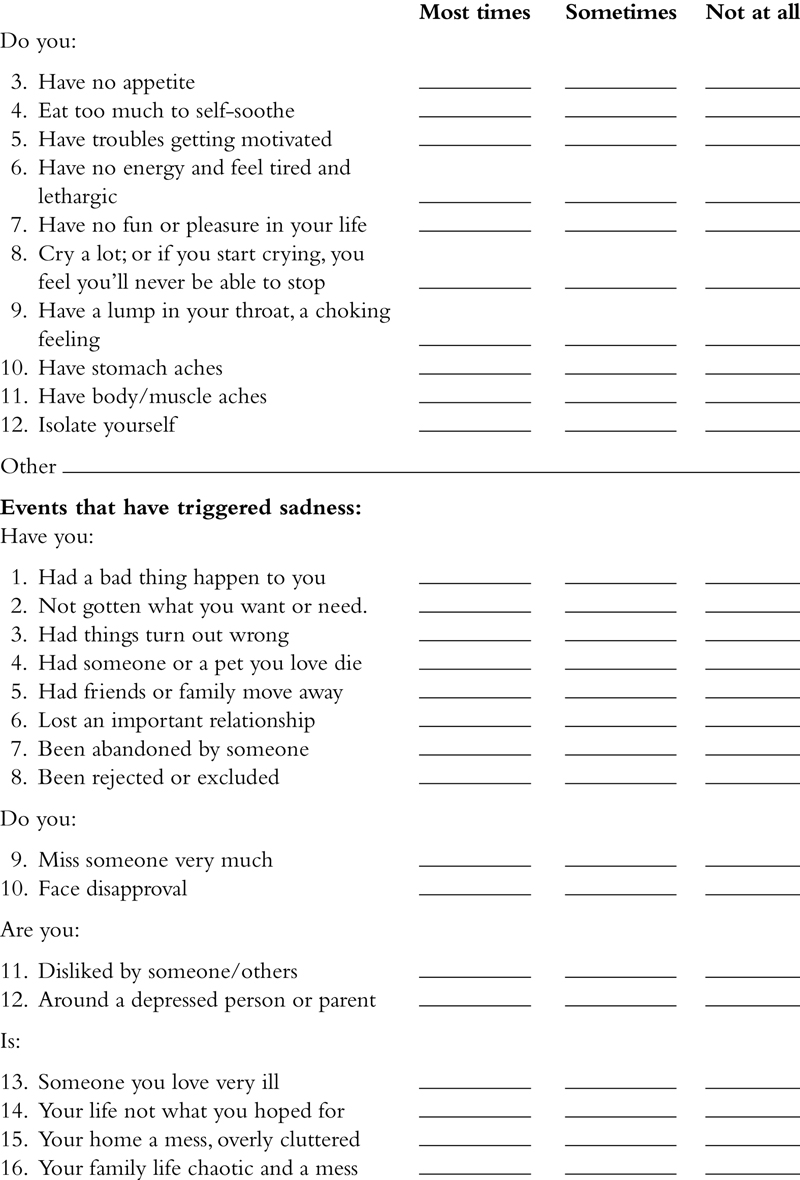

The checklist at the end of this chapter is designed to help the parent or an older child to identify various things that might be contributing to the child’s depressed state, coping strategies, and ways to redirect depression towards positive experiences and thinking.

5.8. Develop Positive Thinking and Shape Positive Behaviors

Often the child who is depressed is a pro at negative thinking, turning their mind quickly to the worst possible scenario. It is often helpful to talk with them about the worst thing that can happen to “lance the boil” so to speak. Could they stand it if that really happened? The child may fear a terrible illness will befall them, that someone might die, or that their close friend or relative will leave them. The reality might be that one of these things might actually happen and the child needs to take realistic steps to cope with the possibility of these things happening. Preparing for the worst that can happen allows the child to avoid being blindsided and taken unaware. It is also important for the therapist to give the message that they can endure the distress of the child’s life with them, that they can bear it, and move to a better place (see Skill Sheet #12: Thinking with a clear mind).

In the face of terrible events that might happen or have already happened, the child needs to take charge of what is positive in their life, spotlighting the good things about themselves and their situation. Taking stock of personal strengths and positive attributes is very important. What helps the child to endure strife? What winning characteristics of the child help them to get the support they need from others? How can we build resilience in the child to continue forward and seek the comfort and support they need? When parents have a difficult child who is disruptive or oppositional, it is a good idea to “catch them being good”, noticing moments when the child is doing something positive. The same is true for the depressed child—they have to catch the child in positive moments and fan the flame to make more of these things happen. Some people like the idea of putting a spotlight in their mind on positive thoughts and putting negative thoughts “in the dark.”

5.9. Address sensory regulation issues. Introduce light

Some depressed children are in a chronic state of shutdown and withdrawal and suffer from sensory deprivation. They may develop a lifestyle that has very little stimulation, or in the case of children with bipolar illness, they may overstimulate themselves constantly. It is important to identify what is comforting and what is irritating to their nervous systems. Visual and auditory stimulation may be intensely overwhelming for them. It is very useful to figure out what is self-calming to the child and the optimal number and type of activities for the child in a given day. Planning out a daily and weekly schedule of pleasurable activities will help the child to begin to anticipate and tolerate stimulation.

Often children suffering from depression feel worse in the winter months. A full-spectrum light box can offer relief to individuals who have seasonal affective disorder. This can be an important intervention, especially if used during the morning hours.

5.10. Learning to communicate with others in prosocial ways: the ice-cream sandwich

Often the child who is depressed, irritable, and angry derails social interactions by communicating in ways that turn other people off. It is helpful in therapy to talk through how to approach others to promote listening and communication (see Skill Sheet #20: Communicating effectively with others). The child should figure out what they want to have happen and what they want others to hear or understand. In essence, the structure of the communication is like an ice-cream sandwich with two positive statements and a request or message sandwiched in between. The theory behind this is that the child is more likely to get positive engagement with others and receptivity if they can learn to be positive in how they deliver their messages. For example, Connor was accustomed to bossing family members around, telling them what to do and how, and if they didn’t cooperate with his plan, he screamed, slammed doors, or stormed out in a huff. No one in his family liked him or wanted to spend time with him. We made a list of things he wanted to communicate with his family and we thought through how to convey the messages using the ice-cream sandwich. Here’s an example:

Instead of screaming at his family, “I want a new skateboard right now. All my friends have the latest one and mine is all beat up. I hate my life. This family sucks,” Connor was able to come up with the following:

Positive statement: “It would be really nice if I could skateboard with my friends on the weekend.”

Request: “Would it be possible for me to do chores to earn money towards the purchase of a skateboard?”

Positive statement: “I would have a good time with my friends and when I come home, I will help get ready for dinner.”

5.10.1. Communication and problem-solving skills—Using GREAT FUN to be a better negotiator with people

Great Fun is an acronym that can help a child stay focused while communicating to others successfully. Often depressed or highly reactive individuals are ineffective in their communications to others which can lead to more mood dysregulation, poor problem-solving skills, and ineffective negotiations with others.

Here are the components of GREAT FUN.

• G—What is your goal? Grace felt constantly criticized by her mother for isolating herself in her bedroom. She frequently felt badgered for the way she left her belongings helter-skelter in the mud room and for not helping out more with chores. Grace wanted her mother to understand that she was exhausted and depleted after a day at school of interacting and paying attention.

• R—Review the situation. What are the facts? Grace acknowledged that she was disorganized, depressed, and overwhelmed that she couldn’t get herself motivated to do any essential tasks around the house for her family.

• E—Express how you feel: Grace felt like a failure in her parents’ eyes, compared to her older successful brother, and hated when her mother yelled at her for leaving messes in the house and for lying in her bed looking at her electronics after school.

• A—Ask for what you want: Grace identified what would help her to do a few things successfully for the family and came up with something to say to her parents that would make her feel more validated. “You know I have been feeling very depressed and out of energy after school. I would feel better about myself and our relationship if I could be supported instead of criticized. Could we try three things that would help me to get started, like you letting me have a 45 minute break after school to chill, helping me organize my back-pack for the next day, and texting me on my phone messages like ‘It’s time to start homework’ or ‘It’s time to come help with dinner.’ I would also like you to notice when I am making efforts to lift my mood and interact with the family.”

• T—Think about why the other person might do it or see things your way: “If you can try not to criticize me, I will feel more positive towards you and want to spend time with you instead of avoiding you all the time.”

These communications need to be done with FUN. This acronym captures how the child does the GREAT.

• F—The child needs to be Fair. Grace needed to realize that her parents’ patience was wearing out, that they had been dealing with her isolation, messiness, and snarky behavior for several years. They had reached their limit.

• U—Understanding. Grace needed to listen to what her parents had to say to her about the situation, trying to understand their perspective. In particular, her mother said poignantly that she felt unloved by Grace when she always wanted to get away from her and that she wanted a relationship with Grace like they used to have.

• N—Negotiate. The child needs to learn to meet others half way. In Grace’s case, we arranged a schedule of relaxation, refueling her energy, responsibilities for school work and family, and time with her family and friends that helped her restore a balance in her life.

5.11. Developing an understanding of experienced emotions

Many children experiencing depression feel numb and unable to define the emotions that they feel. They often have a limited range of emotions, primarily feeling gloomy or sad most of the time and not knowing how to experience pleasure, joy, excitement, or assertiveness. Some individuals describe it as if their emotional life was flat and they do not know how they feel about things. Others feel so absorbed by their black cloud that no other emotions can be experienced. It is important in treatment to help the child read their internal emotional experiences and connect them with bodily sensations and thoughts. As the therapist helps the child observe what he might be feeling and why, it offers the child something to react to and to begin to attach words to feelings. This process helps the child develop a specificity to his internal emotional life that can be very useful as he moves through his day-to-day life outside of therapy. It is very important to tie feelings that the child experiences to what they are sensing in their body. For instance, how do “sad” and “angry” feel different for the child? The child may shutdown with both emotional states, but when feeling sad, they notice that they feel very tired whereas when they are angry, they wish to retreat but their heart is pounding.

5.12. Changing negative thoughts to positive ones

Once the child has learned to recognize his feelings with more specificity, it is important to identify the negative cognitions he holds and consciously change negative thoughts to positive ones. These cognitions may be things like, “I am a failure,” “I cannot stand it,” “I do not deserve,” or “I am not good enough.” In therapy it is useful to “unpack” what goes into the negative cognition. For example, Rick installed the feeling that he was a failure since his childhood when his parents constantly offered attention to his older sibling who suffered from cerebral palsy and couldn’t feed himself. Rick felt undermined and never received attention for his accomplishments, his good grades and sports awards going unnoticed. He felt that his role in the family was to stay out of the way and be “the good boy.” Understanding the underpinnings of the negative cognition is very helpful. The therapist should assist the client in identifying what situations evoke the negative cognitions along with the accompanying physical sensations. For example, in Rick’s case, he felt incompetent at school and home, feeling that he never measured up to his parents’ expectations which reinforced his feeling that he was a failure. He experienced a sinking feeling in his stomach and often felt like he was invisible. He was able to identify specific situations that reinforced his negative cognition. His teachers often overlooked Rick when kids were raising their hands to answer questions or to participate in special projects. His mother often ignored him when he walked in the door after school. Each time these things happened, Rick felt reinforced that, yes indeed, he was the failure that he always thought he was.

Stopping negative thoughts is easier said than done because the cognition is usually integrated into the child’s personality and is reinforced repeatedly by social situations and the child’s own behavioral responses. To change negative cognitions, it helps to first calm the body through self-soothing activities, deep breathing, and visualizations of a safe place (see Skill Sheets #1: Self-soothing, #7: Mindfulness: Stilling the mind, and #8: Systematic relaxation: Stilling the body). When the negative thought enters the mind, the child should think of it as a toxin to the body that is detrimental to both body and mind (see Skill Sheet #12: Thinking with a clear mind). To stop negative thoughts, the child should redirect their thoughts and actions as soon as the negative thought enters their mind. Visualizing a stop sign or red light, saying “stop it,” and pinching the wrist or snapping a rubber band around the wrist sometimes helps. It helps to think about soothing the part of the body that is affected by the negative thought. For example, Rick felt his distress in the pit of his stomach and a feeling that he was no longer present. He visualized a warm gold light that filled his stomach, taking deep breaths that warmed his gut and calmed his heart. To feel present and visible, he took a moment to study his hands, gazing at the details of his fingers, the shape of his hands, and becoming very aware of their weight and feel. Sometimes it helped him to go to the bathroom and look in the mirror to see his presence, that he was not invisible.

The next step to changing the negative cognition is to reframe the script that runs through the mind to a positive cognition. For Rick, it was “I am worthwhile” and “I am loved.” While saying these mantras in his mind, he learned to do things that changed the negative social reinforcement that he had been receiving. At school when he felt overlooked, he decided to take action to try to do an outstanding job on existing projects and to sign up for after-school clubs. We developed an action plan of how to make this happen with week-by-week goals. When he arrived home from school, he came in the door to his family and immediately went up to his mother, asked how her day was, and shared something that happened that day at school. These subtle changes helped to change the social dynamics that were supporting the negative cognition.

5.13. Address rigid thinking

Some children suffering from depression become quite inflexible and rigid in their thinking, having difficulty taking into account another person’s perspective. It is not uncommon for the child to project onto others the negative cognitions that they feel about themselves. As one helps the child to be open that others are likely to have a different point of view than they do, it is important to help them open their mind to other ways of thinking about a situation. People suffering from depression often blame themselves or others for their problems or they overpersonalize situations, ascribing innocuous things with personal meaning. It’s helpful to guide the child to speculate what others might be thinking and to avoid thinking in words like “always, never, every time, everyone, or no one.” Likewise, the child may jump to the conclusion that the worst possible outcome will happen or they believe that their negative feelings are true without questioning them.

Matthew hoped one day to be a professional soccer player. He played on the school team in his middle school years but suffered from low self-esteem. He held the view that no matter how good he was at soccer, he was never perfect enough. He had a very low threshold for frustration and when learning the sport, he was quick to criticize himself, sometimes lost it on the field when he missed a shot, or devalued himself in front of his teammates. Matthew had developed a view of the world that everything he did was constantly being evaluated and critiqued, with no room for error or fun. The other children often avoided Matthew after the team had played a game or talked about his short fuse on the field to one another. To help address his rigid thinking pattern, we first focused on him developing a calmer internal state to decrease the physiological agitation that accompanied his frustration and inflexible thinking. It was not uncommon for Matthew to scream at his teammates or to storm off if the team lost. Matthew was coached to take a break, excuse himself for 5 minutes, calm down, then return to the field more able to play with a patient, team spirit.

After the child is calm, they need to put into place effective coping and problem solving skills. The child needs to be taught steps toward effective problem solving, breaking the problem down into each component. The first step is to define the problem with emphasis on how it impacts not only the child but other persons in the situation. Second, the child needs to think through possible alternatives to the problem and its pros and cons. Lastly, determine which solution is best and why, then evaluate whether it was effective for the child and others involved. As one works with the child in these problem solving situations, it is helpful to inquire what they are thinking and feeling and what other persons might be thinking and feeling as well. Stepping out of themselves to think of others’ thinking is often difficult for the child who is not mindful of others’ perspectives.

In the example of Matthew, I once inquired what his teammates might think or feel when he was impatient with them and yelled at them. He looked at me with a stunned expression and said, “I guess they feel really bad that they screwed up their shots.” I asked what they might think of him and he replied, “I had never thought of that before. They must think I’m a real jerk who doesn’t like them.”

Matthew had never thought about his behavior in this way and realized that he was passing on his critical self-state to his teammates and felt badly that he was injurious to them. It took some time to change both his negative thinking and behaviors, but learning to be mindful of others’ thoughts was a step in the right direction.

5.14. Strategic emotional regulation: when to act on emotions, to take opposite action or do nothing?

Many children who are depressed submit to their depression and become inert. Children with bipolar illness or depression accompanied by irritability and anger may feel compelled to act on their impulses or emotions. The first step for better emotional regulation is for the child to be strategic with their emotions. This requires the child to identify their feelings, to tolerate their existence, and to separate their feelings from their behavior. It is useful for the child to think through what the end result is that they would like to accomplish, then to decide whether it is in their best interest to take opposite action to their instinct, or to wait, tolerate the emotional state, self-distract and self-calm, and do nothing to avoid more negative consequences. The latter is especially important for children with bipolar illness or anger management problems who tend to react or do manic activities that derail them.

A dialectical behavioral therapy technique that is very effective for depression is taking opposite action. If the child is lethargic and wants to do nothing, the opposite action would be to make a list of things to do, move or exercise, or do something small that they can accomplish in the next hour. Suppose the child secludes themselves from others and feels that it takes too much effort to interact with people. The opposite action would be to call someone to talk to, plan a social event that would give them pleasure, or go someplace where people gather, such as a playground.

A common negative emotion of depressed children is to feel like they are worthless and a failure. The focus needs to be turned away from perfectionistic performance and toward task completion. Often the child freezes and does nothing for fear of failure, then gets negatively reinforced by others for doing nothing. The child needs to take opposite action by completing some aspect or all of the project at hand, immersing in the task and deriving pleasure from accomplishment, or shoving all judgmental comments from others out of their mind.

Children with depression are overwhelmed with sad, depressing thoughts, walking around home and school with a black cloud over them. The child’s reality is depression and it may not go away even with medication and therapy, but they can redirect their focus from being self-absorbed to other-focus and see if this brings more pleasure in their life and sparks interactions with others. Other-focused activities might be paying attention to family members and friends, noticing funny or amusing things in the news or when out and about in the world, or on doing something positive for others that would be construed as helpful, loving, or caring. Pushing negative thoughts out of the mind when feeling disgust, shame, anger, or sadness is helpful while redirecting the mind toward positive and pleasurable thoughts and actions. Self-soothing activities, meditation, mindfulness practice, and other sources of pleasurable experiences need to be a major focus in the depressed child’s life.