Eating problems in children can be very overwhelming to parents who struggle to find foods that their child will eat and who may have behaviors that make mealtimes a nightmare. Parents often worry that their child won’t be nourished properly if they eat a limited diet. The child’s oral-motor difficulties may make eating so difficult that the child might aspirate or choke on food. Or the child may have problems sucking, chewing, and swallowing, making the process of eating difficult and exasperating for both parent and child. Some children are so hypersensitive to touch on their face and mouth that certain food textures are aversive to them. There are also children who simply refuse to eat, hate sitting at the table, or have no desire to eat food. There are a range of eating problems, all of which require different approaches.

When therapists work with individuals with eating disorders, they are sometimes confronted with life and death decisions. Is this a child who needs intensive in-patient therapy? Is their weight dangerously low and do they require tube feeding? The anorexic or bulimic child may engage in a passive suicide as they starve their body to death. The adolescent may binge and purge, treating their body as if it weren’t their own and ultimately seeking supreme thinness. Some adolescents may dissociate mind from body as they treat their body as an object. This lack of connection between body, mind, and self is extremely difficult for the therapist to endure. Often the adolescent feels overwhelming shame about their body and may view felt desire as a threat. When this occurs, the therapist may fall in the trap of doing anything possible to resurrect a sense of desire for the child who is running on empty.

The child with an eating disorder may be preoccupied with repelling nurturance. There is an ensuing battle between a wish for control of the body and a desire to nurture oneself or be nurtured. The rigid control of eating and food can overtake the person’s life. This can be quite effective in pushing away intimacy. The child may make food a weapon and what is taken into the body becomes their focus rather than engaging in meaningful and satisfying relationships with others. Some individuals eat highly restrictive diets and are picky eaters. Others obsessively dictate how a food should be prepared or served, sending food back and making the whole mealtime experience very unpleasant for others.

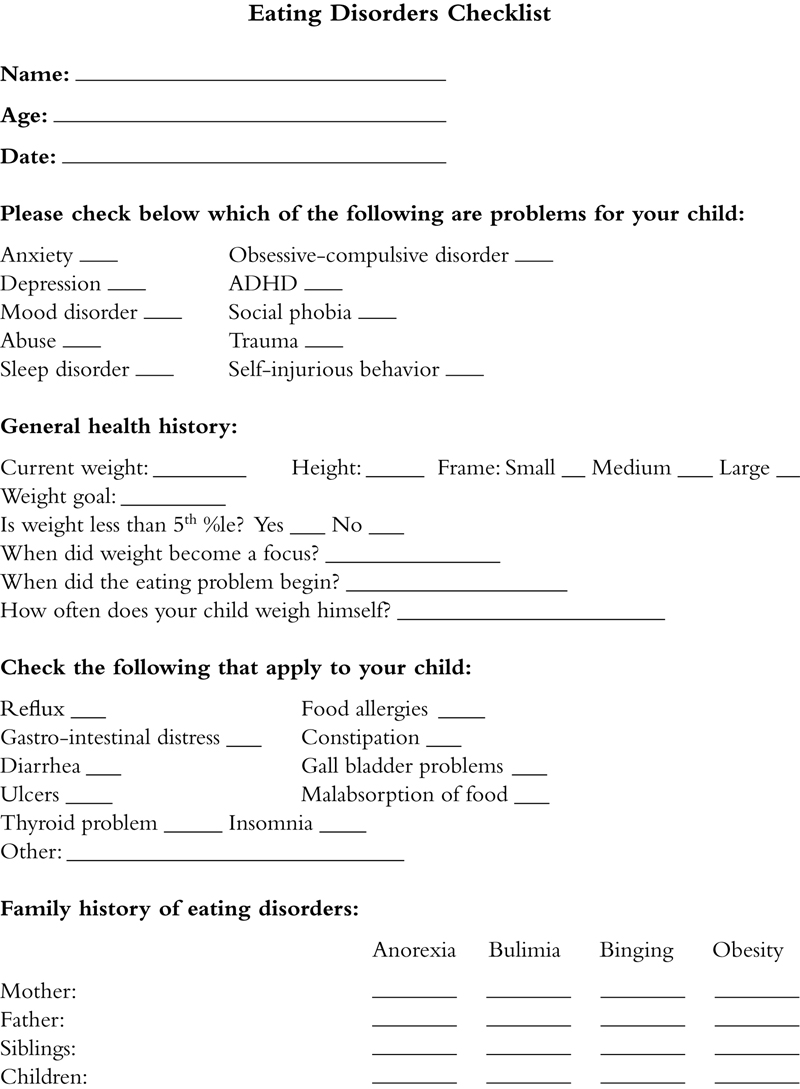

When there is an eating-disordered child, family members often worry about the person’s weight, whether he is overweight or too thin. Food becomes a big topic for the whole family and often a parent who has an eating disorder will transmit eating problems to their own children. It becomes contagious. In some cases, parents may constantly offer their child things to eat. Instead of three main meals, it becomes constant grazing, a sure way to kill off normal appetite drive. This chapter will give a brief overview of what goes into children becoming good eaters, the different kinds of eating problems, and what parents and therapists can do to help those problems. Three case vignettes are presented that depict different types of eating disorders and how they are addressed in therapy. The checklist at the end of the chapter is designed to assist the clinician to delineate specific feeding problems and any emotional difficulties underlying the eating disorder as well as to identify treatment goals.

1. The many facets of eating?

When a person is a healthy eater, they show that they can organize around a mealtime schedule, self-regulate food intake, and control their body. It also demonstrates a healthy response to being nurtured by others and nurturing themselves. Just like sleep patterns, there are many variations in how families eat, what types of foods they eat, and what the family mealtime looks like depending on the family’s customs and culture. Regardless of these variations, there are certain emotional and developmental tasks that all persons need to be self-regulated in their eating patterns. Here are some of the things that go into healthy eating and mealtime experiences.

• There are numerous sequences that require the person to be well organized and planful to make a successful meal. There is the menu planning and food preparation, setting the table and creating the mealtime ambiance, getting family members to come to the table, the act of conversing, eating, and enjoying one another’s company during mealtime, clearing the table, and cleaning the pots and dishes.

• During meals, parents need to enact mealtime rules for their children, such as requiring the children to sit in their chairs while eating, using their utensils in appropriate ways, and to not throw food.

• Family members learn to remain seated for a short period of time, pay attention to the mealtime experience and conversational discourse, and contain their activity level for the duration of the meal.

• The experience of food requires people to tolerate a variety of sensory experiences involving taste, smell, and tactile sensations to the mouth and hands.

• Social interaction and communication skills are major aspects of mealtime. Family members listen, take turns, and keep up a conversation in a group while eating.

• The child asserts their autonomy by making food choices, deciding how much food is eaten, and how they will eat food (i.e., finger foods, use of utensils).

• Parents help their children learn how to be flexible in transitioning from whatever they were doing to come to the table and to tolerate changes in the mealtime or feeding routine. For example, the child might be urged to eat a new food, to eat in different places like restaurants, and to manage different seating requirements.

• The person gains the satisfaction of nurturing themselves through food, fixing food that appeals to them, and enjoying the experience of eating with others.

2. What can go wrong?

There are many ways that eating can go off the rails. Some people are born with problems that cause them to have an eating disorder. Others have emotional problems that interfere with self-regulation of eating. Most times, it is a combination of the two. Some children have reflux, which can cause eating to be a painful experience. Tactile hypersensitivities may be present in the mouth causing the child to reject food textures or to gag when eating certain foods. The infant may pull away from the nipple, reject food textures, gag when presented with certain foods, or have difficulty being held and fed. Altered capacity for interoception, the senses of pain, temperature, taste, muscle tension, and stomach and intestinal tension, is often affected in individuals with eating disorders. This sensory disturbance provides the link between body state, cognitive appraisal of hunger and satiety, and affective drive to seek food. It is important that intervention do not overlook interoceptive feedback mechanisms.

Medical problems related to malabsorption of food or failure to thrive in early childhood may exist and affect weight gain lifelong. Some individuals with eating problems suffer from severe reflux (acid indigestion) or multiple food allergies, which complicate the eating process. Occasionally the person has sustained a traumatic incident, such as

choking on a particular food that may result in an aversion to eat. However, when there are no medical reasons for the childhood anorexia, the child is apt to have significant emotional problems that underlie the eating problem. Often the problem has roots in infancy and early childhood. Research has shown that high irritability, perfectionism, obsessive–compulsive disorder, harm avoidance accompanied by anxiety and inhibited behavior, and a drive for thinness in early childhood can predispose a person for an eating disorder (

Litenfeld, Wonderlich, Riso, Crosby, & Mitchell, 2006;

Anderluh, Tchanturia, Rabe-Hesketh, & Treasure, 2003). About 50–70% of persons with anorexia are treatable but don’t usually resolve until their mid-20s, however, they usually persist in their personality traits of negative emotionality, perfectionism, and desire for thinness (

Strober, Freeman, & Morrell, 1997). These same traits are common to children with anorexia which suggest that they are part of the disorder rather than a secondary aspect of the problem.

Eating problems may also develop because of emotional problems in learning how to self-regulate, to become attached to others, or to assert appropriate self-control and autonomy. These difficulties may be manifested by self-inflicted fasting and refusal to eat, rejection of the breast or foods, or other behaviors, such as verbal fussing or agitation when exposed to certain foods. Needless to say, feeding issues are very complex and often evoke considerable anxiety in therapists, family members, and the individual facing the problem.

Some children have such severe feeding problems that they fail to gain weight and grow. These children are termed

“failure to thrive” (

Benoit, 1993;

Chatoor, 1989;

1991;

Chatoor et al., 1985). There are a number of reasons that a child can have this problem. Some children have a medical problem, such as a malformation of the esophagus or a problem called reflux (i.e., severe acid indigestion) that contributes to the growth disturbance. Then there are other children who have developmental difficulties that alter their ability to swallow and chew properly. The most puzzling children are those who have no developmental or medical reasons for their failure to thrive. These children tend to have more sensory and emotional problems that underlie the problem. Regardless of the reason for the failure to thrive, it seems that most children who struggle with the task of eating eventually develop some emotional difficulties related to the feeding problem. The reason for this is because feeding happens in the context of the relationship between the child and his or her caregiver.

A common eating disorder of unknown etiology is anorexia nervosa. This problem is characterized by severely restricted intake and a striving for thinness. A failure to maintain weight at 85% of the expected weight for the person’s height and age is one of the criteria. In menstruating females, missing three consecutive menstrual cycles occurs when weight becomes alarmingly low. Usually anorexia emerges in early adolescence and is more common in females. Interestingly the anorexic resists eating and is in constant pursuit of weight loss, yet at the same time, they are obsessed with food and eating rituals. It is frequently reported that the anorexic has a distorted body image, viewing themselves as fat when they are extremely thin. These individuals fail to perceive themselves as underweight and often they compulsively overexercise and undereat.

There are two paths that the person with anorexia takes. One is to restrict food intake by constant dieting. The other route is binge eating and purging. These individuals usually restrict food intake but lose their capacity to disinhibit intake and engage in binge eating. A binge is considered one in which the person eats far more than most people would eat in that period of time. There is usually a lack of control in inhibiting food intake when binging. Following a binge, the person induces vomiting or other means, such as misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or excessive exercise to prevent weight gain. It has been thought that the person with

bulimia is similar to the anorexic in risk factors (

Walters & Kendler, 1995). The underlying disturbance with either anorexia and bulimia is likely to be a disturbed appetite drive coupled with anxiety over weight gain. Appetite drive is controlled by the hypothalamus, which helps to regulate food intake and body weight. However, recent research is showing that the reward centers of the brain related to serotonin and dopamine metabolism link feeding behavior and emotion regulation (

Kaye, Frank, Bailer, & Henry, 2005). These individuals may find little in life that is rewarding to them other than pursuing thinness. Contrary to persons with depression, people with anorexia tend to have an increase in binding potential of serotonin (

Bailer et al., 2007). Individuals with anorexia may find that restricting dietary intake helps to reduce anxiety whereas eating causes a dysphoric mood (

Vitousek & Manke, 1994). Their appetite is clearly altered and they may not be able to identify hunger states.

Another type of eating disorder is the person who engages in binge eating, also known as pathological overeating without purging or fasting to lose weight. There is a distinction between these individuals and those who are obese and do not binge. Bingers tend to overeat for long periods of time, sometimes even for days at a time. This eating pattern continues for at least 6 months or more. The person often can’t differentiate fullness and satiety because they are always in a state of eating. Most adolescents who binge have troubles with self-soothing and food becomes their medication of choice. It is important to distinguish between a person who binges and overweight individuals who tend to graze on food all day or eat high-fat foods. Binge eaters seem to fall into two categories: deprivation-sensitive binge eating or addictive/dissociative binge eating. Persons who engage in deprivation-sensitive binge eating often have been on weight loss diets or restrict their eating, then afterward end up binge eating. The addictive or dissociative binge eater does so to self-soothe and may feel numb, dissociated, or extremely calm after binge eating. Treatment of individuals who binge is difficult because weight loss can trigger binging.

Finally, in the DSM-IV TR, there is eating disorder not otherwise specified. These are individuals who share many traits with anorexics and bulimics but do not meet their diagnostic criteria. In the United States, it is estimated that as many as 10 million females and 1 million males have an eating disorder of some type. Eating disorders commonly occur with other diagnoses including anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and social phobia. Posttraumatic stress disorder and sexual abuse have also been associated with eating disorders. Finally, self-injurious behaviors (e.g., cutting) may also occur in persons with an eating disorder.

Whenever a child has an eating disorder, it affects their physical health and emotional well-being. They often experience problems with low body energy, sleep, high irritability, and frequently they have conflicted relationships with others. The anorexic or bulimic is apt to experience muscle wasting and weakness in muscle strength, as well as other health problems including stomach ulcers and reflux. Social and emotional problems with disordered attachment relationships occur because of the disruption in the person’s capacity for nurturance and normal control of themselves and others. If there is an eating disorder, it is important to find out whether the problem has a medical origin or if the eating disorder has created a medical problem. For instance, a teenage boy had gall bladder illness and became very nauseous and frequently vomited his meals. After several months of an unidentified medical condition, he developed an eating disorder, which later persisted even after his gall bladder problem had been fixed. Once you have determined the presence of any medical problem impacting eating, it is then useful to explore what emotional issues have developed or existed over time. Sometimes the child has experienced deprivation, abuse, or trauma in their lifetime. To help understand the interplay between eating and emotional development, the three main stages of feeding development are next described focusing on what is normal and what can go awry.

3. The developmental stages of eating

3.1. Stage 1: learning to self-regulate

The first stage of development is when the infant gains the ability to self-regulate himself to self-calm, and to have cycles of sleep, hunger and satiety, feeding and elimination. These basic rhythms of life are essential for self-regulation. Becoming a successful eater in infancy depends on having a coordinated suck and swallow, being calm but alert during feeding, and the ability to signal when hungry or full. The infant orients their body and mouth toward the mother’s breast or the bottle, tolerates contact of the nipple in the mouth, and accepts being held in a suitable position for feeding. During the early months of life, the infant must also learn to signal when he is hungry and satiated. For this cycle to occur, the baby needs to have periods of quiet alertness so that his or her parents can differentiate between different types of crying related to hunger, other bodily discomfort, or a wish to be held and comforted. In the early months, eating and digesting food efficiently often impacts sleep–wake cycles.

For feeding to go well in the early months of life, the caregivers need to learn how to read their baby’s cues and help them to regulate rhythms of eating, wakefulness, and sleep. The more skillful the parent is at interpreting hunger signals and to establish an eating and sleep schedule, the easier the process seems to go.

3.1.1. Problems with self-regulation and how they affect feeding

Feeding problems at the stage of self-regulation are complex and may relate to the basic ability to read body signals related to hunger states, sensory processing, and oral-motor control of suck and swallow. When problems occur in these areas, they are likely to affect the development of successful feeding as the child matures. Some children may confuse being hungry or full with the need to eliminate. Problems of this type are common in children with sensory integration disorder who have poor processing of the sensory receptors in the gut and colon. Five-year-old Amy could go long periods without urinating, but when she finally sat on the potty, she would release a flood of urine. She also did not know when she was hungry and could go all day without eating unless reminded by her parents that it was time to eat. She often had no appetite, which worried her parents because she was so tiny for her age.

Sometimes parents have difficulty helping their child read their signals of hunger and satiety. It might be hard for them to know when their infant’s cry is because of a wet diaper, overstimulation, or hunger. Sometimes the baby doesn’t give a clear enough signal for the parent to read. For example, Colin would scream constantly regardless of whether he was hungry or not. At age 2, he had no words and used screaming to express anything he needed, as well as when he was unhappy or distressed. The only discriminating scream was when he was thirsty for juice. He would scream in front of the refrigerator, and when he wanted Cheerios, the only food he ate, he would scream in front of the cupboard. One can only imagine how frustrating this was to his parents who didn’t know what he wanted most of the time and had to either assume what he wanted or play “20 questions” to find out what he was screaming about. When children are like this, the parents may resort to feeding the baby to console them, thus setting up a cycle whereby the infant expects food whenever distressed. A baby who is constantly fed may not experience the sensations of fullness and hunger, a problem that seriously affects appetite drive.

A worried caregiver whose baby is not gaining weight may try to repeatedly feed their baby every hour or two in hopes that the baby will eat. Oftentimes the baby senses the parent’s anxiety and becomes increasingly resistant to eating. The child may feel his signals are misunderstood by the parent and may consequently reject eating experiences.

In other cases, the child may not be fed on a regular schedule. If the mother or father is depressed, they may have trouble conjuring up the energy to meet their child’s needs. Sometimes a parent doesn’t naturally know how to nurture because they didn’t grow up with a nurturing parent. That makes it hard for them to know when to comfort and feed their child when he is distressed. There are also families who don’t have enough money to provide regular meals. Likewise, a stressful family situation can make it difficult to respond when the child is hungry. For example, some parents work long hours and cannot juggle work and home life to be conducive for regular mealtimes. In these situations, the child may learn that he cannot get the nurturance he needs or they can’t get into a regular rhythm of eating at certain times.

This problem was demonstrated by an 8-year-old girl, Samantha, who was referred to me for treatment because she was stealing food from friends at school. At home, she had developed a pattern of eating anything in sight. She had a sister slightly older than herself who had physical challenges and needed a lot of help to do the basics of eating, dressing, and day-to-day activities. As a result of her sister’s physical needs, she was always fed first and Samantha had to wait. As a baby, Samantha was very placid, so her parents thought that it was OK to have her wait while they first cared for Corrine, her sister. The focus of Samantha’s therapy was on her finding ways in her family to feel nurtured—to have special time alone with her mom or dad, and to provide her with experiences that made her feel wanted, deserving, and cared for. As she began to feel nurtured through these therapeutic interventions (e.g., psychotherapy and family-centered interventions), she was able to move past her need to steal food and overeat. She began to assert herself in healthier ways and to take pride in her identity.

Babies who are fussy or colicky often have difficulty regulating a sleep–wake and feeding schedule. They are often easily overstimulated and may respond by not sleeping enough or, the reverse, shutting down and sleeping for long periods at a time. The baby who stays awake and cries constantly is often inconsolable. Parents struggle to find ways to comfort their baby and may resort to the constant use of the pacifier or multiple bottles throughout the day. When this occurs, the infant may not take in an adequate amount of food at any one time to feel satiated. The constant snacking on a bottle often results in a baby who never experiences hunger or satiety, thus prolonging the pattern of dysregulation. This problem was demonstrated by 10-month-old, Maddy, who cried almost constantly, sleeping erratically, waking 7–8 times in the night to feed, and only calming when sucking at her mother’s breast. The mother, exhausted by her irritable baby, found that the only way she could get some rest was to sleep with her baby with her breast constantly available to Maddy throughout the night. The mother worried that her infant was hungry all the time and she became anxious that she could not fulfill Maddy’s needs for nurturance. This became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Over time, the mother’s breast milk supply became inadequate and the child began to scream in hunger when the breast would not satisfy her.

A less common scenario is one in which the infant shuts down completely as a result of feeling overstimulated. This usually occurs because of significant problems that the child has with sensory hypersensitivities. The infant may sleep for long periods of time or nap constantly as a means to shut out noise or other sensory confusion. In his first year of life, Christopher slept almost 20 continuous hours of the day. Needless to say, when he was awake for the 4 remaining hours of the day, it was hardly enough time to eat enough to sustain his development. He was often sluggish during feeds and his parents needed to rough house with him to arouse him for eating. The parents thought that Christopher needed a lot of sleep and were not concerned until Christopher turned 1 year of age and was not talking or walking. In addition to failure to thrive, Christopher had significant developmental delays which improved dramatically once we regulated his sleep and eating schedule.

Many children who struggle with self-regulation also have sensory integration dysfunction. A very common problem is hypersensitivity to touch around the mouth, which may cause the child to reject the nipple or new food textures. Likewise, infants who cannot tolerate being held during feeding may arch their backs and struggle out of their parent’s arms. They may cry because the tactile contact is experienced as aversive or because the position of the body is uncomfortable for them due to vestibular-based or muscle tone problems.

Oral tactile hypersensitivities can greatly interfere with early feeding. Some babies react to the nipple touching their lips as if touched by an electric shock. Latching on and sustaining a suck may be difficult because of problems sustaining skin-to-skin contact. The baby with this problem often pulls away from the breast or bottle and screams in distress. Some babies clutch their hair or body and flail their arms and legs about in obvious distress over the tactile contact. Mothers feeding a tactually defensive baby become extremely anxious that the mere act of holding and feeding their baby evokes a severe reaction. The mother may quickly feel depressed and anxious about feeding the baby. This problem was depicted by Stephen, who at 6 months was rapidly losing weight, and showed a severe defensiveness to touch around the mouth and face coupled with a weak suck. He had low muscle tone and felt floppy when held or picked up. His mother found that Stephen would eat a good sized bottle while sleeping, so she began to look for ways to feed him while he slept. Stephen was also hypersensitive to sounds and tended to shut down and sleep whenever the room was filled with people talking or laughing loudly or she was running the vacuum cleaner. By chance, his mother discovered that she could feed him while he was asleep. Soon she began to use the sound of the vacuum cleaner to put Stephen to sleep and would then feed him. Addressing his sensory hypersensitivities was the first step in helping Stephen to overcome his eating problem. We began by helping him to tolerate touch in the mouth using Nuk toothbrushes and his mother’s finger massaging his gums and cheeks. We worked to help him tolerate sounds through cause–effect toys that made music or interesting sounds. At the same time, we provided him with a calm environment at home with little stimulation at a time to decrease his tendency to shut down when overstimulated. These ideas, together with oral-motor activities to improve his suck and swallow, helped to launch Stephen’s ability to be fed and feed himself.

A common problem related to oral tactile hypersensitivities is rejection of different food textures, which usually emerges around 9 months of age. Some infants develop a preference for firm smooth textures and prefer eating foods, such as crackers or crunchy cereal. When this occurs, the infant is usually seeking proprioceptive input to the mouth by selecting foods that allow them to bite. Foods with uneven textures, such as applesauce with sliced bananas are often rejected. Problems with oral-motor control particularly weak tongue movements, low muscle tone in the mouth, and incoordination of swallow and breathing patterns need to be ruled out. An occupational therapist or a speech and language therapist can help evaluate this problem.

Another common sensory problem that affects the feeding process relates to the vestibular system. Some babies are distressed by the natural feeding position because of sensitivities to body position in space. Usually these babies dislike being placed down in supine or prone positions and prefer to be upright. Often the mother abandons breast feeding for the bottle because she finds that the only way she can feed her baby is in a more upright position, usually sitting in the infant seat or high chair.

At times a baby will have such severe sensory hypersensitivities and motor planning problems that they are challenged by the task of coordinating suck and swallow, feeding, maintaining tactile contact with the nipple, and looking at the mother’s face at the same time. When this occurs, the mother may observe her baby looking away from her face or the baby may arch away. Sometimes the mother finds that feeding is more successful when the baby is fed with a bottle in a sitting position facing away from her body. As a result, the feeding experience becomes one that is no longer intimate, taking on a mechanical quality. One mother who had to feed her child in this way expressed how she felt cheated of the experience of breast feeding her baby. As Jeremy grew older, he continued to avoid social contact at meals. The only time he enjoyed mealtimes was when he could watch videos or be in a restaurant with ceiling fans that he could watch. In this example, the child had learned to detach himself from his parents and the eating process.

3.1.2. The impact on parents when the child has poor self-regulation in eating

Parents who experience a child with poor self-regulation often become depressed and anxious. They frequently state that they feel inadequate that they cannot feed and nurture their child. When opportunities for nurturing in normal channels are disrupted, the parents may feel at a loss for how to establish a connection with their child. Most parents describe feeling demoralized and rejected by their child. As the parents become more agitated about the child’s eating problem, both parents and child develop high anxiety around the feeding experience. As a result, there is confusion in the signal reading and giving between mother and child. One mother described how she herself had been a fussy baby and a picky eater growing up. As a teenager she was very thin and felt a lack of appetite drive, needing to be reminded to eat by others. When pregnant with her first baby, she was anxious that eating would be a problem with her baby, fearing that Josh would reject her breast or be a fussy eater. In the first few days of life, the mother was puzzled by her own reaction when the nurse brought Josh to be fed, feeling that her baby was overly demanding and bothersome to her. She expressed the feeling of being “sucked dry by this little creature” instead of welcoming her baby’s normal desire for feeding. Needless to say, the baby developed a significant problem in expressing hunger and satiety, often going for long periods without eating. When his mother returned to work when Josh was 6 months, he would wait for over 12 hours at a time to be fed, insisting that only his mother could feed him. In this situation, the baby had become as anxious about feeding as his mother had, but demanded that only his mother could feed him.

3.2. Stage 2: attachment

The capacity for attachment is intimately related to the persons developing a reflective sense of self.

Bowlby (1980) describes how development of the self can only occur in relation to the experience of oneself in intimate relationships. At 6 weeks, the infant begins to gaze up at the caregiver, smile, reach for her face, and cuddle or mold toward the breast while feeding. There is a wonderful sense of intimacy between mother and child that emerges while the baby suckles. Although there is a strong sense of oneness between mother and child during the feeding experience, very early in life, the mother and child develop a reciprocal relationship, vocalizing back and forth, mutual gazing at one another, and enjoying interchanges of smiling and cuddling. The feeding experience is a very important aspect of building the attachment bond.

A number of longitudinal studies examining attachment in infancy and childhood have found a high consistency between attachment patterns in early and later life (

Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). There is a strong intergenerational transmission of pathology in attachment relationships. Research has also found that adults who are securely attached are much more likely to have children who are securely attached to them (

van IJzendoorn, 1995). When a person misses out on being nurtured during their childhood, it makes it difficult to nurture and support their own children’s attachment to them. A child who is rejected or abandoned by their mother or father while growing up may duplicate the pattern with their own children. All they know is a disordered attachment. Usually the person identifies feeling little connection with one or both of their own parents, sometimes not being able to remember their childhood, and describing a lack of physical and emotional closeness with their parents.

In the past 20 years, professionals in the United States have become involved in helping families who have adopted children from foreign orphanages. Many of these children have been institutionalized and have poor attachment. Depending upon the circumstances of the orphanage and the caretaking relationships that occurred, some of these postinstitutionalized children experienced problems with feeding. Parents report that some of the children had their hands held down while being fed so that they could be fed more quickly. Many were exposed to a limited range of foods and would gag if introduced to new textures.

3.2.1. Observing an attachment disorder in caregivers and their children

Sometimes mothers and fathers miss out on being nurtured in their own childhoods, which makes it difficult to nurture and support their own child’s attachment. What happens when a mother or father was rejected by their own mothers when they were children? It is likely that they will have trouble not replicating this pattern with their own child because their experience was one of an avoidant relationship. The mother or father might identify that they had little connection with one or both of their own parents, that they can’t remember times when they enjoyed being with their parents, and there was little physical closeness.

Early experiences with the caregiver serve to organize attachment relationships later in life. In case of the person with borderline personality disorder, they are apt to distort relational dynamics, viewing others as attacking, rejecting, or abandoning (

Benjamin, 1993). In studies of persons with borderline personality disorder, they frequently are classified as having a “preoccupied” attachment. This is characterized by overwhelming feelings of anger and anxiety, strong confusion, and fearfulness in relationships (

Fonagy et al., 1996). These individuals often have an intolerance for being alone and are extremely fearful of abandonment. They frequently do not develop a sense of their own separateness in identity or their own feelings.

Infants and children with poor attachment often avoid gaze or eye contact with other people, including people that are important to them. They may appear listless and apathetic. They may be hypervigilant in looking around the environment, but avoid eye contact when approached by someone. They usually do not like to be hugged or held by loved ones. Sometimes they are developmentally delayed in their skills, largely due to the fact that they lack the motivation and drive to explore the environment. When problems with attachment affect feeding, the child shows many of these same attributes, but in particular will show a lack of pleasure in feeding and in playing with the caregiver. Usually the child has little appetite which may be an indication of an underlying depression in the child, a lack of signal reading and giving between mother and child, or a low motivation to feed.

When problems with attachment affect eating, the person shows a lack of pleasure and interest in eating with a low appetite. Or they become obsessed with food and never seem to feel nurtured and filled up physically and metaphorically. Importantly, they are not able to perceive their own body, and are therefore, forced to try to experience themselves from the outer environment. This can result in very high anxiety, insecurity within, and a high need to control and manipulate objects, food, and people. The person focuses on their weight as a way of creating a sense of self-worth, control, and a state of well-being on the one hand, and self-punishment, self-blame, and self-destruction on the other. In the anorexic, they may strive to be the thinnest, even if it kills them.

3.3. Stage 3: becoming separate

The period between 6 months and 3 years is an important one in building the capacity to separate from the caregiver and develop a sense of self. The infant first discovers their independence when they crawl away from the mother and realize with both delight and fearfulness that they have wandered away from their mother’s lap. Negotiating when to be dependent and when to be autonomous begins. Cause and effect understanding facilitates the awareness that the baby’s actions cause a reaction in the caregiver. This can be easily seen when the baby throws the cup on the floor and the caregiver picks it up, returning it to the high chair tray only for it to be thrown again by the baby, much to the child’s delight and parent’s dismay.

By the time the baby reaches 7–9 months, he becomes interested in finger foods, using utensils to self-feed, and trying new food textures. The baby is progressing from a stage of total dependence on the caregiver for feeding to one in control of the feeding experience. For success in accomplishing the task of self-feeding, the baby needs to feel comfortable separating from the parent, and to feel a sense of competence that they can nurture themselves and control what goes into their own body. Between 12 and 18 months, the normal infant learns to assert themselves through feeding and play. Some infants begin to refuse certain foods at this time, sometimes even favorite ones, but it is usually a temporary phenomenon unless the child is not given enough autonomy. Part of the process of becoming separate involves the child learning that their body is separate and distinct from their mother and father’s bodies. This begins when the baby may experiment by biting on the mother’s nipple as he feeds. The infant begins to give clearer signals when distressed, full, hungry, or tired, and the caregiver needs to be responsive to these cues.

As the child develops competence in self-feeding, the mealtime becomes a time for the family to socialize and come together around eating. The child gestures and uses words, enjoys being the center of attention, wishes to be admired, and laughs whenever anyone laughs to try to be part of the group. As the child grows into the preschool years, he begins to learn the give-and-take of offering food to one another, as well as the turn taking that takes place in conversations at mealtimes.

The sensory experience of eating changes as the child embarks upon the task of self-feeding. The sensory aspects of eating may become a challenge for both child and parents alike. In a typically developing baby, the baby usually enjoys dipping their hands in food and soon their face may become smeared with baby food. This tactile experimentation with food may or may not be met with pleasure depending upon the child’s tactile system. Likewise, the parent who is uncomfortable with messes may struggle with how messy their baby can get when trying to self-feed. As the infant develops the motor control to manage the spoon, cup, and finger foods, the parents need to be comfortable in allowing their baby to take charge of the task of self-feeding.

During this stage of separation and individuation, issues may develop around the infant’s capacity to exert autonomy versus dependency. When parents insist on feeding their child past the point that the baby wants to be fed, the baby may resist the process by pursing their lips and turning away from the spoon, or engage in other behaviors, such as banging their head, arching out of the high chair, or throwing cups, bowls, and food off the food tray to express their dissatisfaction in being controlled. Other children who are fed by their parents during this stage may develop a passivity about eating, and may later develop a dependence on their parents doing things for them. The child’s refusal to eat may be a way to get the mother’s attention or to express anger at her. At the dinner table, the child may engage in food throwing, tantrumming, or extreme food preferences with random refusal of preferred foods. Some parents may resort to feeding their child as he walks about the house because the child is so difficult to feed in the high chair. Some children with low weight may be forced to eat past the point of satiation, which often results in vomiting the meal. The parent usually becomes angry and more forceful about the child’s eating, often trying to introduce another meal within an hour or two. The child may begin to feel that they are held hostage in the high chair with no way to assert control except by compressing their lips and turning their head away.

3.3.1. What can go wrong at this stage?

Eating problems at this stage are characterized by refusal to eat or extreme food selectivity. The feeding problem seems rooted in the infant’s assertion for autonomy whereby the mother and child become immersed in a control battle around eating. The parents have usually tried everything to get the child to eat—distracting (one parent plays circus clown or entertainment committee), bargaining (eat the peas to get a toy), force feeding, and coaxing. Instead of allowing the child’s own body to regulate what and how he eats, the focus becomes the emotions that occur around eating—anger and control, caregiver’s intrusiveness, and no natural back-and-forth exchanges between parent and child. The parent frequently experiences feelings of anger, sadness, and frustration and feels completely demoralized that he or she cannot feed their own baby. The parent may worry excessively about their baby’s growth and feel insecure in their role as a parent. Due to anxiety about their child’s eating, the parent may become flooded by emotions and consequently cannot read their own child’s cues.

Conflicts around eating can easily prevail through childhood and into adulthood. A dynamic arises whereby family members try hard to be loving toward the eating-disordered child, but at the same time, may feel angry at them for using food as a battle for control. It is also very common for individuals who were forced to sit and eat until they had cleared their plates to raise their own children in a similar way. This may set up a pattern of binging and purging. Often the child with a long-standing eating disorder remembers their parent becoming angry and more forceful about their eating, often introducing another meal soon after the last one to ensure more intake of food. The child grows up feeling that they are held hostage at the dinner table with no way to assert control except by refusing foods. Mealtimes become defined by behavioral resistance and conflict. In others, the conflict is more internal. Binging and purging help the person modulate discharge of tension and anger at themselves and others. If the person doesn’t purge, they feel anxious and out of control.

An example of this was demonstrated by Jonathan who was brought in by his mother when he was 11 months for assessment because he was refusing to eat. As we observed Jonathan and his mother, we noted how Mrs. P. worked very hard to try to get Jonathan’s attention during play. Her attempts to get him to look at her felt desperate. Jonathan would look away from her in a very purposeful, almost defiant way. During mealtimes, Jonathan refused to eat whenever his mother approached him with a spoon or cup to feed him. The only way that he would eat was when he could take charge of the feeding, but he purposely refused certain foods set out by his mother. He tended to eat better when the nanny fed him during the day. Mrs. P. felt further rejected and had begun to force feed Jonathan in hopes that he would allow her to feed him.

4. The assessment process

As assessing and treating the child with failure to thrive or other eating problem is so complex, a multidisciplinary team is needed that consists of a physician, a mental health professional, such as a child psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, or social worker, a speech and language therapist, nutritionist or pediatric nurse, and an occupational therapist. Infants and children should receive a comprehensive set of assessments in order to delineate the nature of the feeding disorder. Close collaboration between members of the team is integral in order to assure that the evaluation and treatment process does not fragment treatment services or further disrupt a family under extreme stress. In addition, a primary pediatrician must be involved to monitor weight gain and address any medical complications that may arise.

The assessment process that is suggested includes the following:

1. An initial intake interview should be conducted by a mental health professional to identify parental concerns, obtain a complete medical and family history, and document previous treatment approaches. Evaluating what the eating problem serves for both child and family is important to determine. The child should be weighed and measured for height and head circumference, and a food intake history should be given to the parents to complete. The presence of supplemental feeding procedures (e.g., nasogastric tube feedings or gastrostomy tube feedings) should be documented as well.

2. The child’s second and third visits should consist of a developmental assessment and feeding observation that includes developmental, sensory, motor, oral-motor, feeding, and language functions. In addition, parent–child interactions should be observed to

provide an index of the child’s emotional development within the context of the mother–child interaction. The Functional Emotional Observation Scale provided in

Chapter 1 may be used as a guideline in observing these interactions. This visit should be conducted by an occupational therapist, speech and language pathologist, and a clinical psychologist.

Observation of a family mealtime is very useful in assessing family dynamics in how eating is handled, how the mealtime is structured and food is served, socialization between family members, and how the child eats or is fed. Sometimes it is useful to observe several family meals, particularly if some meals tend to go better than others. Videotaping several mealtimes may be an option if a videotape camera is available to place in the home environment.

Specific observations of the child’s oral motor and feeding abilities may be further assessed using the

Oral-Motor/Feeding Rating Scale (

Jelm, 1990). It is a scale designed for children from 1 year of age through adulthood. It includes sections on oral-motor and feeding patterns, areas related to feeding (i.e., adaptive equipment, sensitivity), respiration/phonation, and gross and fine motor function. It is designed as a rating scale to document qualitative difficulties in oral-motor and feeding skills.

This evaluation process should be followed by a parent conference to discuss the team findings, recommendations for treatment, and setting of goals with the family. The checklist at the end of this chapter can be used to delineate specific feeding problems, emotional problems underlying the feeding disorder, as well as treatment goals.

5. Treatment intervention

The treatment program is multifaceted and needs to address the child’s physical growth and nutrition, the feeding process, the parent–child relationship and issues of attachment and control, constitutional factors, such as sensory defensiveness to touch, weak suck and swallow, and emotional capacities of both parent and child. Oftentimes a multidisciplinary team is needed including a pediatrician, a child psychiatrist or psychologist, social worker, occupational therapist, and nutritionist. Hospitalization may be necessary when the child experiences severe problems related to malnutrition, refusal to eat, or depression. A primary aspect of the treatment is fostering a healthy attachment between parent and child. The child who may have seemed developmentally delayed may show rapid growth in cognitive and physical growth but slower changes in behavioral and emotional development (

Harris, 1982) as the treatment begins.

In developing a treatment approach for children with nonorganic failure to thrive, it is important to identify the emotional conflicts that may be contributing to or prolonging the feeding disorder. A developmental classification of feeding disturbances based upon Greenspan’s stages of early emotional development (

Greenspan & Lourie, 1981) has been developed by

Chatoor, Hirsch, and Persinger (1997). It takes into account the

different types of feeding disturbances and indicates at which stages emotional development is compromised.

Treatment intervention should be directed at resolving issues of homeostasis, attachment, and separation that affect the capacity to feed and the ability to engage in reciprocal and age-appropriate mother–infant interactions during mealtimes. Since hypersensitivities to touch and movement may interfere with the feeding process, it is critical to address sensory processing needs as well. The treatment approach is based upon this model, which recognizes the emotional development of the child, related sensory dysfunction, and the impact of the feeding, sensory, and emotional problems on the family and parent–child relationship. An integrated treatment approach that includes child-centered activity focusing on unresolved emotional issues (

Johnson, Dowling, & Wesner, 1980;

Mullen, Garcia Coll, Vohr, Muriel, & Oh, 1988;

Robin, Gilroy, & Dennis, 1998;

Wesner, Dowling, & Johnson, 1982) should be used in conjunction with occupational therapy or speech and language therapy approaches to ameliorate oral-motor and sensory problems. This treatment is described in detail in

Chapter 10.

Selection of professionals to be involved with a particular child should be based upon the specific needs of the child and family within the treatment process. The intensive treatment sessions should consist of the following elements:

1. If sensory aversions are present,

address tactile hyper or hyposensitivities in the mouth and body (see

Chapter 9). Use of a vibrating toothbrush or waterpik will help desensitize the mouth. It is also helpful to stimulate the olfactory sense with warmed foods that smell enticing (i.e., baked bread, cinnamon on a baked sweet potato).

2. When diet is very limited, begin with firm food textures at first and then expand the food repertoire beginning with smooth, soft textures before uneven textures. To boost appetite drive, introduction of zinc supplements is often found useful. Due to the health risks of fasting and purging, vitamin supplements, protein drinks, and omego-3 and omega-6 fatty acids should be incorporated into the diet.

3. Address motor needs in holding utensils. For example, you can use a Nuk toothbrush or a breadstick as a spoon because these things may be easier for the child to grasp. Use sticky foods for the spoon, such as melted cheese on peas or mashed potatoes. Begin with foods that the child can eat on her own, such as bananas and bread. For those messy meals, put a drop cloth under the high chair to make for easy clean up. Some parents find that allowing the child to eat without a shirt on is easier. If food spills on their body, it will help them to become less hypersensitive to the touch. Avoid wiping the child’s mouth throughout the meal, particularly if the child is hypersensitive to touch. Instead, dab the face with a warm damp terry cloth or preferably wait to clean the child’s face at the end of the meal.

4. Establish rituals at mealtime including hand washing, setting the table, creating ambiance for a setting conducive to sitting, socializing, and eating, as well as a routine for clean-up after the mealtime so that dishes and pots are cleared and cleaned.

5. Label being hungry and full before and after meals to help the person recognize these states. Develop better interoception of the gut by working on deep breathing and expansion of the abdomen. A large weighted pillow may be placed on the abdomen to increase sensation.

6. Therapy should focus on being “present” in one’s body, to feel one’s body during mindfulness exercises (i.e., mindful eating to taste and chew food slowly). Contract-relax muscle exercises help to highlight body awareness. Focus on the “here and now” to process and receive sensory stimulation from others and the environment and to internalize and receive interactions from others.

7. Work with the gastroenterologist or pediatrician around monitoring weight and dietary needs. It is helpful to set a weight goal that is 18–25% body fat and 90–100% of the person’s ideal weight for his or her height.

8. Rule out reflux, gall bladder dysfunction, ulcers, or other problems affecting eating with the pediatrician. Address positioning needs during and after feeding to promote digestion.

9. Set up a mealtime schedule for the child. Scheduled snacks may be necessary if intake is very restricted and one needs to increase caloric intake. Protein drinks are useful for snacks of this sort. When seeking to decrease intake in persons who binge, the dinner meal should be smaller. It is a good idea to eat earlier in the evening with no snacking or food intake after 7:00 p.m. Ideally there should be at least 3–4 hours before bedtime to promote digestion. It is also important that the parents avoid any middle of the night bottle-feeding as this sabotages the program.

10. Provide a rationale for mealtimes schedule (e.g., to improve appetite drive).

11. Establish food rules during mealtime so the parents can manage eating with their children and learn to enjoy the mealtime experience (i.e., no throwing of food or utensils; no standing in high chair, one warning, then remove food). This is very important because many children with eating disorders create a chaotic mealtime experience. The structure will also help the child develop better self-regulation of their own eating.

12. Put on the plate only what can be reasonably finished. Avoid putting out too much food (i.e., a whole buffet) because this will overwhelm the child. Avoid preparing special foods for a very limited diet, but have available things that the child likes to eat.

13. The child should sit at the table after putting out food and necessary items for the mealtime. The parents should avoid jumping up to get other foods or cooking something else because the child doesn’t like what they have to eat. A quick alternative should be available for such moments (e.g., cereal, a protein shake).

14. Oral-motor needs related to improving sucking, swallowing, and chewing should be practiced at a time other than mealtimes if possible. Stimulation of the mouth can be done during toothbrushing or playtime focusing on oral-motor games.

15. Food should not be given as a reward for doing other behaviors.

16. Provide opportunities for the person to engage in experiences that promote close attachments and activities that foster separation/individuation, autonomy and control, or other emotional needs underlying the feeding problem. Therapy should focus on helping the child feel good enough in multiple ways—not just appearance, but in talents, relationships, learning, etc. The child needs to feel emotionally filled up by giving to herself in loving ways and receiving love and attention from others. Lots of unconditional love goes a long way. Healthy control of self, activities, and others is important. And most of all, the child needs to learn to feel desire for themselves and that they deserve good things. Therapists and family members should guard against feeling desire for the patient. The eating disorder will not change if this is not addressed.

17. Provide support to the family, acknowledging feelings of rejection and depression from not being able to nurture and feed the child. Address the fear that family members may feel for the eating-disordered child. Often the family fears that the child is too thin or throwing up food and need to find suitable ways to express their worry without blaming the child. Family members often feel helpless and unable to make a rewarding intimate connection with the child.

18. Explore the meaning of food and eating for the parents and child. The therapist should help the adolescent child with irrational, black and white thinking (i.e., “If only I were thin, I would be happier”). If the person inquires, “How do I look? Am I fat?” the family should be instructed to steer off this topic. It goes nowhere fast. Instead, the person should learn to distract themselves to other activities or topics to keep their mind off obsessions about food and appearance. Family members should also avoid making comments about the person’s weight or appearance.

19. Socialize the mealtime experience (i.e., encourage people to eat, talk, and enjoy one another during mealtimes). TV should be eliminated during mealtimes. It is also important that the family not allow the eating-disordered child’s eating pattern to have a negative impact on the whole family’s mealtime experience.

20. Everyone should eat at the mealtime to model eating. If a family member is not hungry or is dieting, they should still try to have a small healthy snack.

21. Encourage the child to go to places where people are eating and enjoying the mealtime experience (e.g., restaurants, eateries, cooking classes, and so on).

22. Acknowledge and respect cultural issues related to feeding and mealtimes.

The intervention should address three main components: (1) feeding and mealtime experiences, (2) emotional needs of the parents and child, and (3) constitutional issues related to hypersensitivities, poor appetite, food aversions, irritability, etc. Sessions may be structured as follows. There may be a brief discussion of the parents’ ongoing concerns with an update of the week’s activities. The child-centered play described later is practiced, followed by a snack or mealtime. The therapist joins the family in the mealtime experience to help model socialization. The session may end with a discussion of how to apply the treatment at home if the treatment is not provided in the home setting. Many parents take this opportunity to further discuss feelings evoked during the play and mealtime experience, issues related to the parents’ own past, parental expectations, and how the child’s problems affected them as a family. More details about the treatment process are as follows.

1. Medical management: Reflux and other medical problems that may interfere with eating should be ruled out. Positioning needs during and after feeding should be addressed to promote digestion whenever reflux is present. Most children do better in a semireclining position for feeding and a period of time afterward to prevent vomiting. Regular weekly weight checks need to be made whenever failure to thrive or anorexia is an issue. In addition, a nutritional consult is invaluable in addressing dietary needs.

2. Child-centered activity is used to focus on unresolved emotional issues (e.g., attachment, autonomy) that are interfering with development of independent feeding behaviors. Parent–child interactions serve as a medium to foster attachment, expression of needs, reciprocal communication between parent and child, and separation/autonomy. The parent’s ability to read and give signals and the child’s initiation of adaptive emotional responses within the context of the parent–child interaction should be promoted.

Nurturing the parents is key to helping the parents nurture their own baby. Addressing issues the mother or father might have related to loss and deprivation is important. As

Fraiberg, Anderson, and Shapiro (1975) have pointed out, it is important to address any “ghosts” from the mother’s or father’s childhood that may cause them to repeat these same experiences with their own baby. When the mother or father is not capable of moving past these barriers and remains severely depressed and/or unable to provide the basics for her child, it may be necessary to find alternate care for the child.

It is important to help the parents understand the developmental conflicts that they are experiencing and how they are expressed through eating behavior (i.e., need for control). To understand this, it is helpful to use a two-pronged approach: (1) use of child-centered activity whereby the parents discover more about the dynamics influencing their interactions and how to be responsive to their child’s emotional needs through play; and (2) the therapist helping to explain the developmental and emotional tasks that the child needs to attain.

During the child-centered play, opportunities should be provided to play about nurturing, feeding, and filling and dumping. Some play materials that many children with failure to thrive particularly enjoy include playing with dried beans, water, and other medium that can be poured into containers. Having dolls and tableware available is useful, but the parents should be cautioned not to lead the child to play about eating if this is not what the child wishes to do. Since separation and control issues are often played about during the child-centered play, play materials that foster this theme should be made available. For example, tunnels to crawl through and obstacles to peek around are useful for separation games. Control themes are often expressed when the child asserts how toys should be played with and where they wish the parent to be in the room. The therapist and parent should watch the child to see which emotional themes emerge and are expressed (i.e., control, deprivation, and so on).

3. Sensory exploration activities are used to normalize hypersensitivities to touch and movement that affect the child’s ability to feed. For instance, the child who cannot tolerate various food textures due to a hypersensitivity to touch in the mouth may be exposed to nonthreatening tactile experiences on the face (i.e., placing stickers on cheeks, puppet play on face), as well as functional self-help activities (i.e., brushing teeth and gums with Nuk toothbrushes). These types of activities help normalize the child’s tactile responses. Addressing tactile problems at times other than mealtimes is often best so that the child will not associate something being done to them at mealtimes. Scrubbing the gums and face gently with a soft scrub brush or terry towel may be done at bathtime. Toothbrushing with firm Nuk toothbrushes is often useful in desensitizing inside the mouth. In addition, firm food textures should be introduced first because these are easier for the child with tactile hypersensitivities, progressing to smooth, soft textures, and lastly uneven textures.

4. Parental guidance is offered to address concerns arising from such issues as food intake, selection of appropriate foods, expansion of food choices, behavioral management at mealtimes, and other similar issues. Behavioral techniques are aimed at allowing normal assertion of autonomy while limiting maladaptive behaviors (i.e., standing on high chair).

Chatoor et al. (1997) have described food rules that are useful in structuring behaviors during mealtimes. A list of modified food rules that seem to work well to promote a healthy mealtime experience for people is given in

Table 5.1.

They may be modified depending upon the individual needs of the person and his or her family, keeping in mind cultural differences (

see Skill Sheet #17: Eating habits and nutrition).

Table 5.1

Food rules for mealtimes

1. Establish a schedule for mealtimes. If your child doesn’t eat a meal, avoid the temptation to try again in another hour. Stay with the schedule. There should be three main meals and two scheduled snacks (in the middle of the morning and afternoon). No extra snacks should be served, even if your child did not eat at one of the meals or snacks. This way your child will start to feel hunger and satiety and understand that when he eats, it satisfies his hunger. When it’s time for the next meal, talk about feeling hungry. After eating, talk about being full.

2. Don’t worry about how much he eats at mealtime. When it’s clear that your child is finished, take away the food and, if your child cannot play unsupervised on the floor, try giving him some measuring cups, tupperware and wooden spoons, etc. while he’s in the high chair. This way you might be able to finish your own meal.

3. Begin with food that your child can eat on his own, such as pieces of banana or bread.

4. Instead of using a spoon which is often rejected when a child has experienced reflux, use something else—like a Nuk toothbrush, or a breadstick for dipping in yogurt, pureed fruit, pudding, or ground meats. Be sure to use foods that are motivating for your child, yet will stick to the utensil. Let your baby hold the breadstick and try dipping while you hold another one to help. Always let him be in control of the “utensil.” You may want to reintroduce the spoon as the breadstick or Nuk toothbrush begins to work.

5. Always eat something with your child. This socializes the mealtime and keeps him interested in eating too. Be careful not to diet when your child is in this program. They will get the message that you are avoiding foods to lose weight and your child will model your behavior.

6. All meals are in the high chair or other appropriate seating. No eating should occur while your child roams the house or is in other places (i.e., bathtub, car seat, and so on).

7. Take plates, food, cups, etc. away if they get thrown. Give one warning, saying clearly “No throw!” If the throwing continues, take your child out of the high chair and end the meal.

8. Let your child self-feed whenever possible. For younger children who cannot spoon feed because they have not yet developed competence at managing the spoon, you can put out a small dish for baby to use while you feed him. Focus on foods that let your child self-feed and that are easy to manage in the hands or by spoon. For example, sticky foods, such as applesauce or pureed bananas are easier than more liquid foods. Finger foods should be julienne strips of steamed vegetables or pieces of fruit or cheese that can be easily managed in the hand and mouth.

9. Limit mealtime to 30 minutes. Terminate the meal sooner if your child refuses to eat, throws food, plays with food, or engages in other disruptive behavior. If your child is not eating, remove the food after 10–15 minutes.

10. Separate mealtime from playtime. Do not allow toys to be available at the high chair or dinner table. Do not entertain or play games during mealtimes. Don’t use games to feed and don’t use food to play with.

11. Don’t praise for eating and chewing. Deal with eating in a neutral manner. It is unnatural to praise someone for chewing and swallowing food.

12. Don’t play games with food or sneak food into your child’s mouth.

13. Withhold expression of disapproval and frustration if your child doesn’t eat.

14. Offer solid foods first, then follow this with liquids. Drinking liquids will fill the stomach so that the child will not be hungry for solids.

15. Hunger is your ally and will motivate your child to eat. Do not offer anything between meals, including bottles of milk or juice. The child may drink water if thirsty.

16. Do the “special playtime” (child-centered activity) before or after mealtime to give your child attention in positive ways.

17. Emphasize mealtimes as a social, family gathering time. In this way, the focus is on socialization rather than worrying about how much your child is eating. Be sure the TV is turned off.

18. All caregivers need to agree to the program or it won’t work!

In the next section, several case examples are provided to depict some of the problems that arise in treating eating disorders. The first case demonstrates how an eating disorder in one or both parents can also lead to a pervasive eating disorder in their child. Treating the family system was important to address the mother’s eating disorder and her attachment with her child. The second case depicts a child who suffered early deprivation and a subsequent attachment disorder that contributed to her eating disorder. And in the last case example, the child has significant food aversions and behavioral resistance at mealtime.

6. Case example 1: it’s a family affair

Ellen and her husband, Drew, sought my assistance to help them with their 18-month-old son, Alex, who had developed severe failure to thrive as a baby. Alex was born full-term at 7 lbs, a good birth weight despite the fact that Ellen had fasted on and off and restricted calorie intake during the pregnancy. She was obsessed about gaining a lot of weight during the pregnancy and wanted to remain thin because of a past history of being overweight. As soon as Alex was born he wanted to be breast-fed. Ellen was immediately angered that Alex would demand this of her after she had just given birth to him. Despite this immediate reaction, she was somewhat relieved that she had enough breast milk to feed him. Alex seemed to be doing well developmentally until he was 6 months old when solid foods were introduced. He wanted no parts of anything by spoon and would twist his body away from the spoon, scowling with distaste. Ellen and Drew decided to continue him on breast feeding as his sole source of nutrition.

By the time Alex was 17 months old, he weighed about 20 lbs. He seemed to have a good appetite for breast milk but never seemed to be full. He constantly wanted to be breast-fed which put Ellen out. She couldn’t stand the constant demands on her, feeling that she was “a big fat cow, a regular milk machine.” Alex had little interest in Ellen other than to be his feeder. He also showed no interest in feeding himself solid foods. His primary way of interacting with Ellen was to appear at her side for breast feeding every few hours.

Ellen and Drew reported that Alex was reluctant to touch or handle foods, especially if they were sticky or wet. The only thing he would touch was dry, firm foods like cheerios or crackers, but he used these to play with, not to eat. He would suck his thumb and allow his teeth to be brushed. He rarely mouthed objects, but when he did, they had to be firm rubber or foam objects. When he sat in the high chair during meals, he would pick up finger foods, then hold them out for his parents to eat. Drew said that Alex seemed to act surprised when they ate the food that Alex offered them. If they offered food on a spoon to Alex, he would compress his lips and turn away.

When I observed Alex, it was clear that his motor milestones were delayed. He didn’t sit until 14 months, crawled at 15 months, and began standing momentarily at 17 months. He said a few words, but whenever I saw Alex, he was completely silent. Drew and Ellen described Alex as a quiet, shy baby who was reserved around strangers. They had taken Alex to a clinic for babies with failure to thrive before they began their work with me. The physician conducting the examination found no physical reason to account for his feeding disorder. She recommended that Alex sit at the table and have the opportunity to see his parents eating foods. She also suggested that they avoid force feeding him, something that Drew and Ellen had tried.

In the first year that I worked with the family, I constructed a feeding team for Alex that included a pediatrician for regular weight checks and to coordinate medical care around his growth. I obtained a family history to determine the presence of eating problems in Drew or Ellen. Both parents ate restricted diets but for different reasons. Ellen ate only grains, berries, and a few vegetables because she claimed that she was highly allergic to most foods but had never been formally tested or found to have real allergies. She was extremely thin and looked borderline anorexic. As a young child, she was forced to finish her meals, even when she was full. She recounted long hours at the dinner table until her plate was clean. Sometimes her mother would rub her face in the food if she did not finish. Her mother would yell at her and say how the farmers would be displeased that they grew this food and she refused to eat it. When she was a teenager, she became quite heavy, weighing about 160 lbs on a small, 5 ft. 2 in. frame. When Drew and Ellen married 10 years ago, Ellen began fasting 1 day per week for weight control. She gradually lost weight and when she became pregnant with Alex, she was pleased that she weighed only 110 lbs.

Drew also had similar weight problems growing up. He described himself as pudgy and was often made fun of by his peers for running slowly and being uncoordinated. In college he adopted a macrobiotic lifestyle and would not eat anything unless it was organic, gluten-free, and dairy free. He had been tested for mercury poisoning and believed that his body was full of toxins, which necessitated extreme caution with whatever he ate. Throughout our work, it was very difficult to make any in-roads into his paranoid and distorted thinking about food and his body. Due to his high resistance, I chose to intervene where the door was open—the focus on his child.

6.1. My early work with the family

In the first year that I worked with the family, I focused primarily on helping Alex to become a self-feeder, to build his sense of autonomy, to foster the attachment with each parent through infant-led psychotherapy (

Wesner et al., 1982), and to help Ellen to have a healthier eating pattern. I was convinced that Alex’s delayed developmental skills were related to his lack of food intake. He appeared listless, pale, and out of energy. Due to Ellen’s fasting regime and her own restricted food intake, I was also very concerned about her eating disorder and whether she had enough breast milk to feed her child. Alex was probably starving.

Our therapy sessions were structured into three parts. The first part was a family mealtime when I modeled healthy eating patterns and offered parent guidance to help Alex with his eating. Due to their severely restricted diet, Ellen and Drew brought food that they liked to eat. Much of the food I considered to be fairly child unfriendly. They were things like seaweed and raw vegetables, which Alex could neither eat nor handle in his fingers easily. I urged them to find things that Alex could hold like peas, rice cakes, and steamed vegetables. It was very difficult to get them to bring suitable food for Alex. I was quite concerned about sabotage of Alex’s eating in these first months of treatment, but eventually they began to understand the need to have food that was appealing for Alex and that he would touch or hold.

The second part of the session focused on infant-led psychotherapy. Each parent played with Alex using a “Watch, wait, and wonder” play therapy approach (

Johnson et al., 1980). Alex initiated all play interactions and Ellen or Drew, whoever was playing with him at the moment, would follow his lead, seeking to discover what their child was needing from them and the environment. This is a very powerful treatment technique that focuses on the dynamics of the parent–infant interaction, insights gained by parents about their relationship with their child, and issues that they may have from their own past, as well as the emotional needs of parent and child. The last part of the session was a debriefing about lessons learned in the session. This was helpful to Drew and Ellen to focus on insights gained about themselves and their child. Both Ellen and Drew were very open to this process and seemed comfortable as we gradually focused on their own eating patterns and how these affected their child.

In the first few months, whenever Alex was placed in the high chair, he would cry, sometimes even wail. Drew wanted to rescue Alex out of the chair, but with my urging, he and Ellen could remain calm and wait it out. Alex showed no interest in the finger foods placed on the tray in front of him. Once he would quiet down, Drew or Ellen would try to spoon feed him soy milk or motion toward the plate of finger foods available in front of him. If they tried to spoon feed him, he would respond with a vigorous compressing of his lips and turning away. I encouraged them to eat their meal while Alex watched, focusing on Alex feeding himself finger foods, and learning to stay in the chair for short periods of time. They offered him finger foods, but he rejected these, vigorously turning away from them. He would cry fiercely and reach for his mother’s breast.

During the play therapy part of our session, Alex would not leave his mother’s side at first and became very distressed if she moved away in the slightest from him. He spent his time touching her leg and looking around the room, only occasionally venturing from her side at a distance of a few feet. Ellen often looked exasperated and put-out. I was struck by how Alex treated his mother as if she were a piece of furniture, never looking at her face and smiling at her. When Drew played with him, Alex would begin to cry and sulk, clinging even more to his mother. We introduced separation games at home, such as crawling chase games, hide and seek, and peek a boo. My thought was to develop autonomy and separation while bridging a connection between parent and child. Within a few months, Alex began to assert himself, saying “no” to his parents during the play. Usually he was very passive and expected his parents to entertain him. At home, he began enjoying going on outings with Dad, but hated it if Mom left the house without him. Alex clearly had a strong need to control his mother.

After a month of therapy, Alex was still not gaining any weight. He would touch the food while sitting in the high chair and would squeeze it in his hands, screaming in anger. I urged his parents to keep at the program and to offer him pieces of jello, sensory mediums to play with, such as finger paints, and to use the Nuk toothbrush in his mouth at bedtime to brush his teeth to address oral hypersensitivities. To facilitate his interest in food, I suggested that his parents introduce food for Alex to smell, such as warm cinnamon bread even though this was not on their diet.