The Sensory Defensive Child: When the World is Too Bright, Noisy, and Too Close for Comfort

Abstract

Many children suffering from mood dysregulation show symptoms of sensory defensiveness. It is very common for children with these difficulties to become extremely agitated when touched by others, irritated by certain kinds of clothing on their body, or angry if bumped in a crowd. Often children with tactile hypersensitivities have difficulty developing close relationships with others—both emotionally and physically. Other sensory channels can be compromised as well. The child may experience sensory overload from being subjected to random or intrusive noises in the environment and avoid situations or interactions with others for this reason. Visual clutter or bright lights may be highly disorganizing especially if the child has attentional problems. Or the child may be extremely fearful of movement to the point that they resist exercise or sports, and avoid places that challenge their balance. A very common attribute of such individuals is a strong tendency to becoming highly disorganized and overwhelmed when there is too much overall stimulation in the environment and too many activities in a short period of time. “Less is better” should be their mantra.

Keywords

1. What is sensory integration?

2. Sensory integrative dysfunction

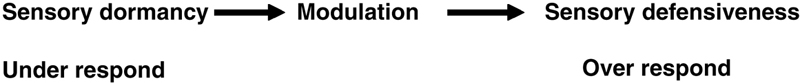

3. The concepts of sensory defensiveness and sensory dormancy

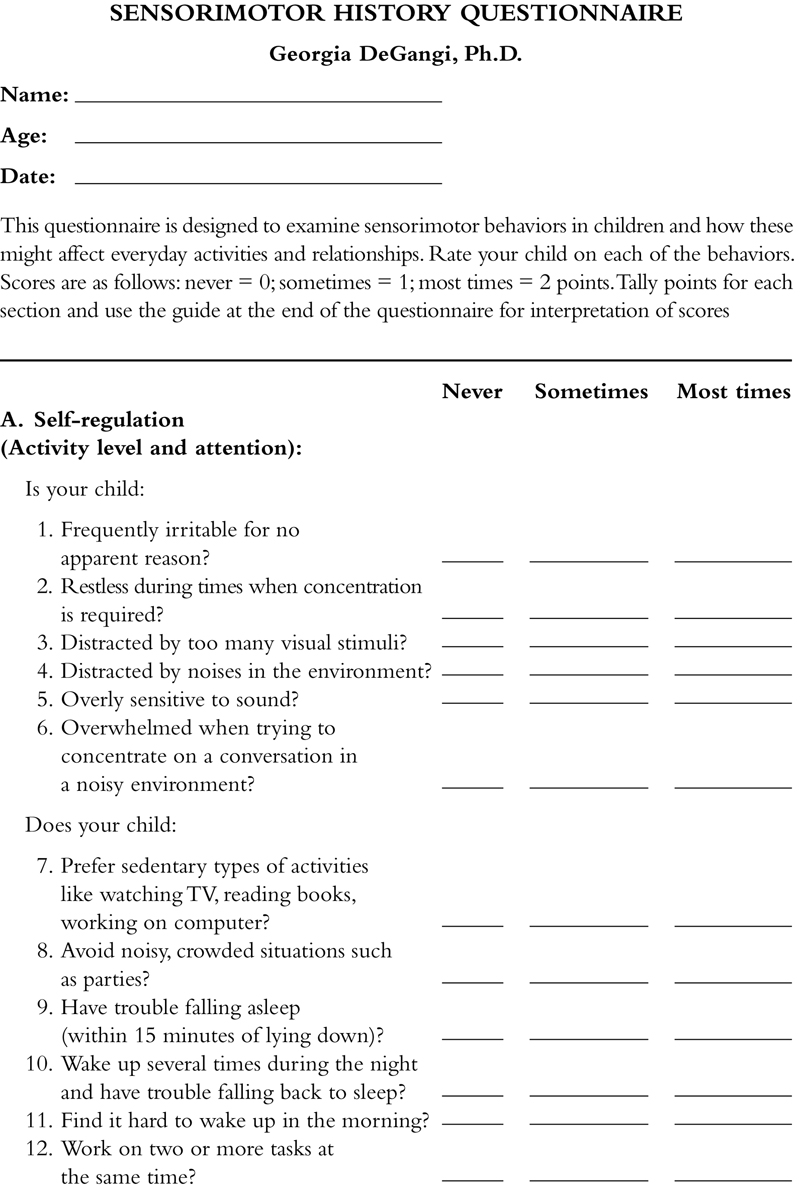

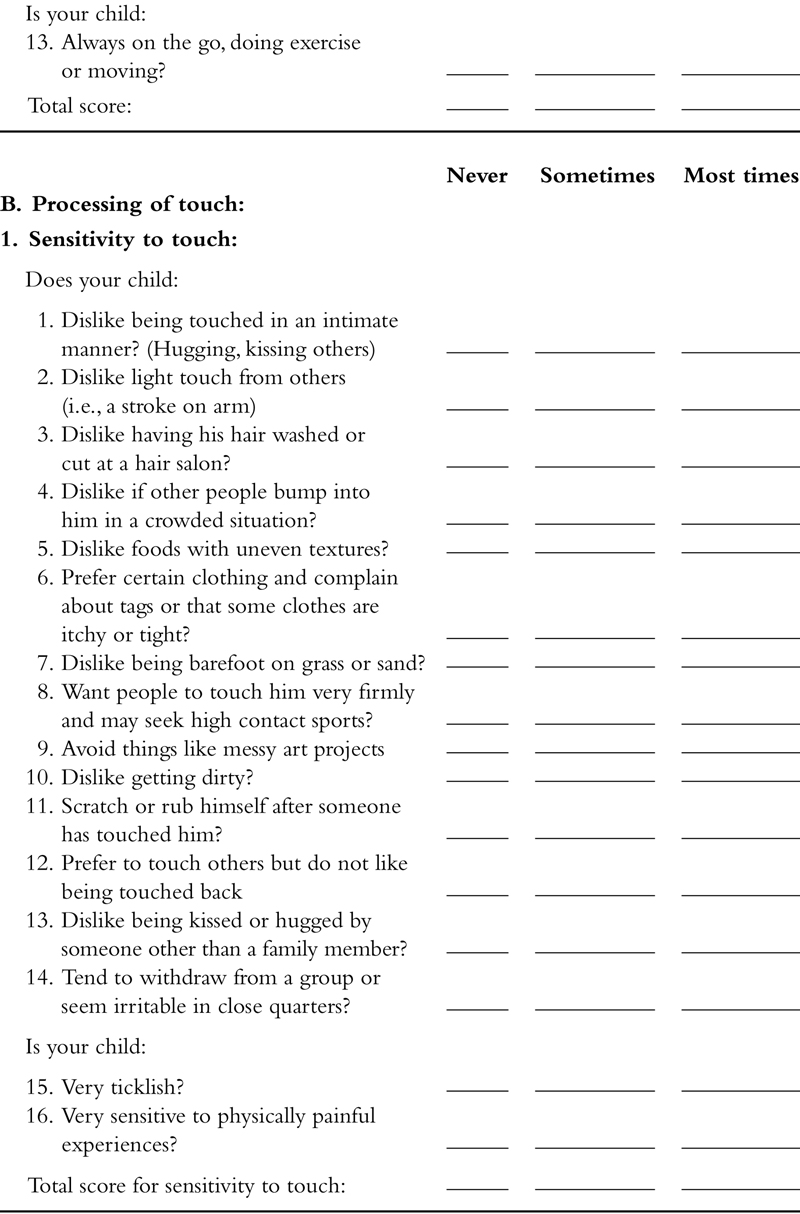

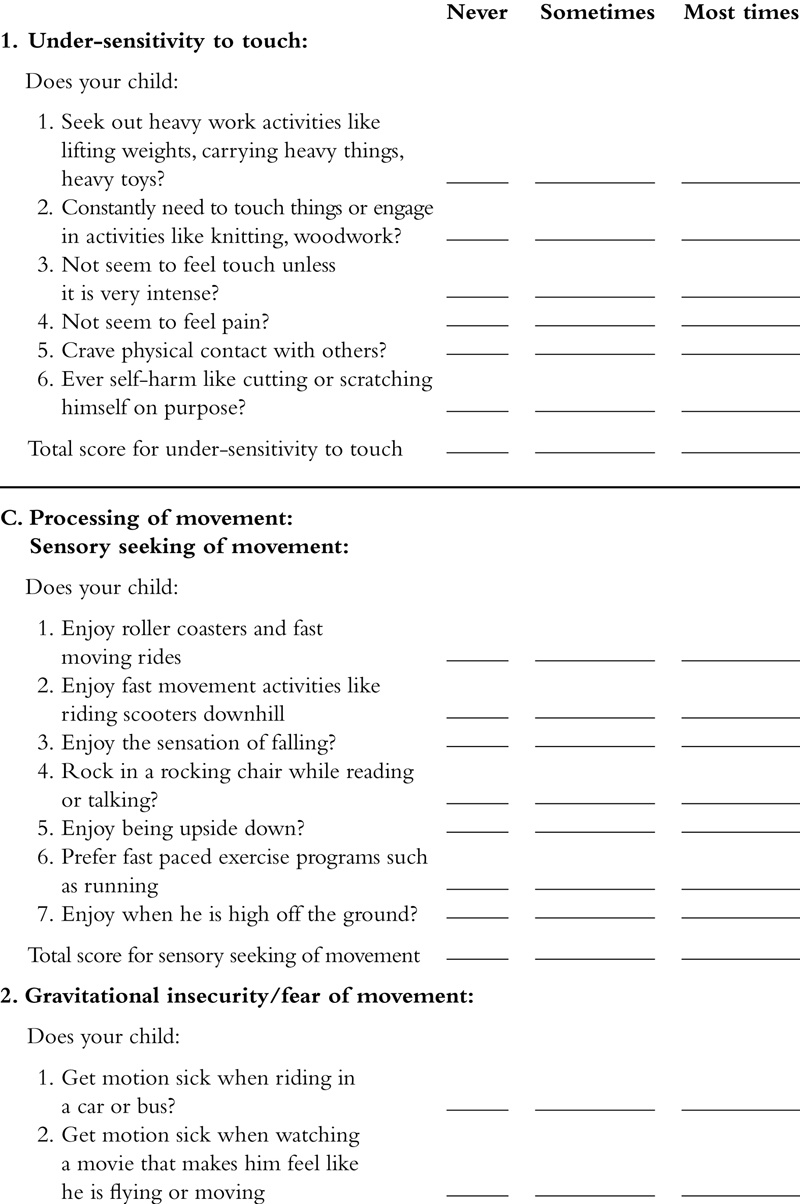

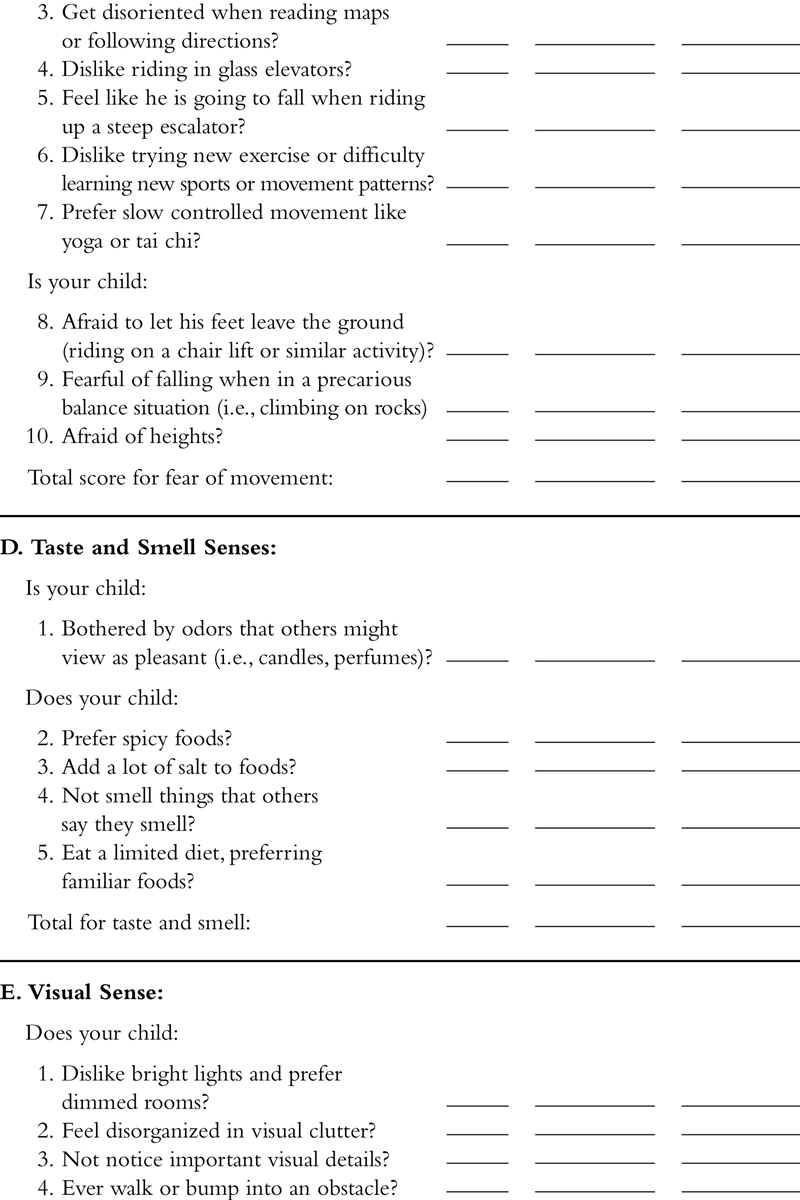

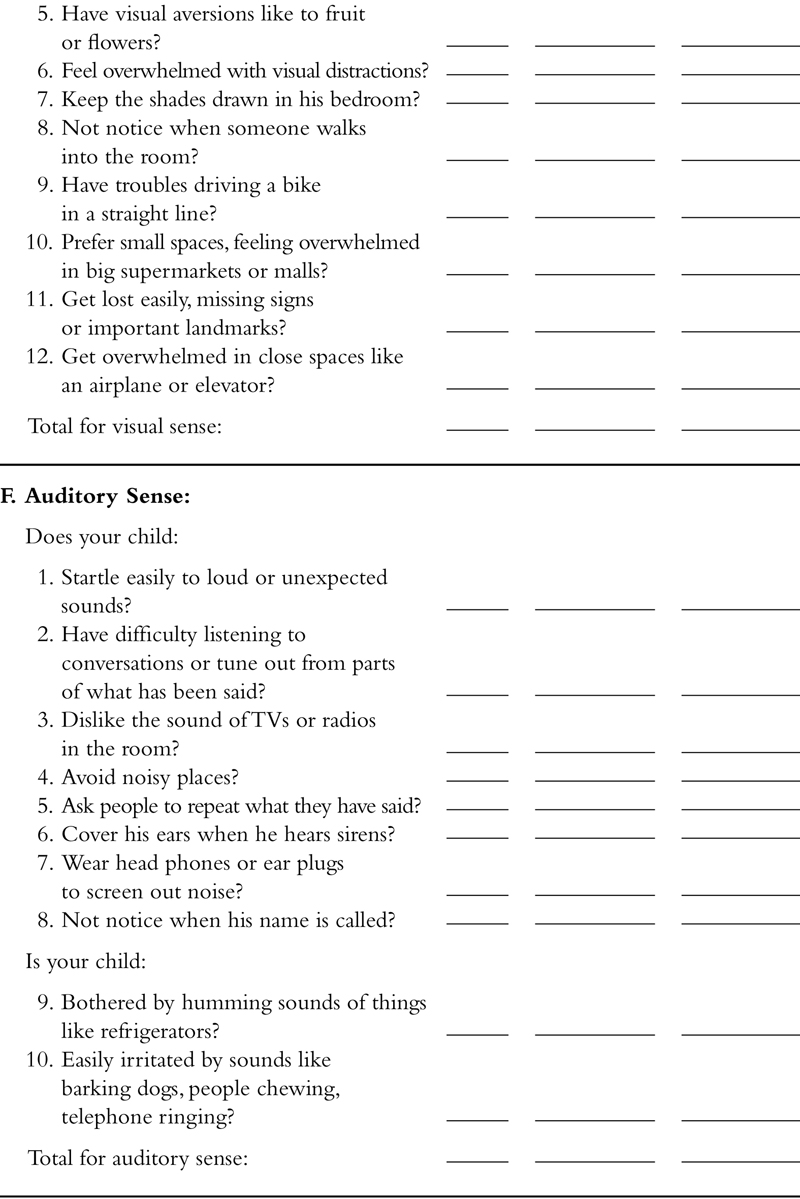

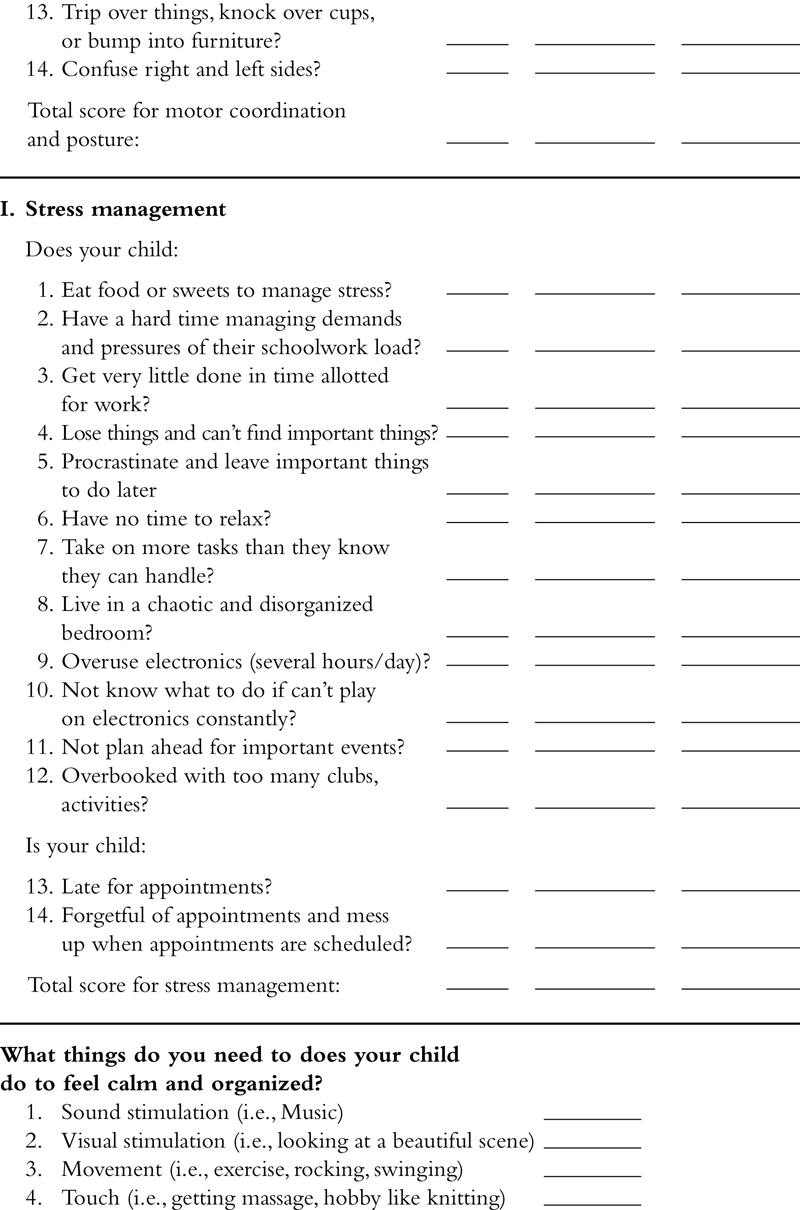

4. Clinical assessment of sensory integrative dysfunction

5. The tactile system

5.1. Tactile dysfunction

5.1.1. Tactile defensiveness

Table 9.1

Symptoms of tactile defensiveness

Infancy:

5.2. Case description 1: tactile defensiveness in an autistic-like child

5.3. Case description 2: tactile defensiveness in a child with motor and language delays

5.4. Tactile hyposensitivities

5.5. How tactile problems evolve over time

5.6. Treatment approaches for children with somatosensory dysfunction

5.6.1. Techniques for the tactually defensive child

5.6.2. Techniques for the child with hyporesponsitivity to touch

6. The vestibular and proprioceptive systems

Table 9.2

Primary purposes of the vestibular system

6.1. Vestibular-based problems

Table 9.3

Common vestibular-based disorders

Table 9.4

Symptoms of vestibular hyper or hyposensensitivities

6.2. Gravitational insecurity and intolerance for movement

6.3. Hyporeactivity to movement in space

6.4. Vestibular-postural deficits

6.5. Treatment approaches to address vestibular problems in children

6.5.1. General treatment principles

Table 9.5

Guidelines for vestibular stimulation activities

6.5.2. Approaches for hyperresponsivity to movement

6.5.3. Techniques for hyporeactive responses to movement in space

6.5.4. Techniques for vestibular-postural problems

6.5.5. Approaches for inattention and problems with self-calming

7. Sound sensitivities

8. Motor planning disorders

Table 9.6

Types of motor planning problems

| Postural dyspraxia | Inability to plan and imitate large body movements and meaningless postures. |

| Sequencing dyspraxia | Difficulty making transitions from one motor action to another and in sequencing movements (e.g., thumb–finger sequencing). |

| Oral and verbal dyspraxia | Inability to produce oral movements on verbal command or in imitation, a skill that affects speech articulation. |

| Constructional dyspraxia | Inability to create and assemble three-dimensional structures (e.g., block bridge). |

| Graphic dyspraxia | Inability to plan and execute drawings. |

| Dyspraxia involving symbolic use of objects | Inability to use objects symbolically. |

Table 9.7

Motor control problems in the child

Table 9.8

Motor planning problems in the child

8.1. Treatment of developmental dyspraxia

9. Case description: the gravitationally insecure child with developmental dyspraxia

10. Case example of treatment approach with child with pervasive developmental disorder

10.1. Presenting concerns

10.2. History

10.3. Clinical findings

10.4. The treatment plan

10.5. The treatment program

10.5.1. The first session

10.5.2. Session #2

10.5.3. Session #3

10.5.4. Session #4

10.5.5. Session #5

10.5.6. Session #6

10.5.7. Session #7

10.5.8. Session #8

10.5.9. Session #9

10.5.10. Session #10

10.5.11. Session #11

10.5.12. Session #12

10.6. Conclusion of treatment

11. Case example of a child with severe sensory defensiveness: therapy spanning from infancy to adulthood

11.1. Ali at 9 months

11.2. Ali at 2 years

11.3. The treatment at 2 years

11.4. The school-aged years

11.5. Ali at 10 years

11.6. The teen years: containing dangerous impulses while creating meaningful attachments

12. Summary