Feeling safe and secure in loving relationships is a difficult challenge for many children with problems of dysregulation. Disorders of self-regulation that often impact the formation of healthy emotional connections are mood disorders including depression, anxiety, OCD, and bipolar disorder. Constitutionally based individual differences including ADHD and sensory integration disorder may also affect the way in which the child interacts with people and how they process social cues. Often the regulatory disorder is coupled with relational disturbances and may represent long-standing problems of attachment (

Sameroff & Emde, 1989). Because there are both biological and emotional underpinnings to the attachment disorder, interventions for children with regulatory disorders should address both of these aspects in developing safety in relationships and emotional intimacy with others.

The most common interventions for children and adolescents with emotional dysregulation, designed to improve relationships, include dialectical behavioral therapy (

Linehan, 1993), emotionally focused therapy (

Johnson, 2004;

Fosha, 2000), and the Circle of Security Intervention (

Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, 2014). DBT is an effective cognitive–behavioral treatment developed specifically for individuals with borderline personality disorder but it has wide application for other types of mood dysregulation. DBT combines individual and group psychotherapy with skills training to help the client to develop core mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance skills. Although it uses skills training, the therapeutic relationship between therapist and client is central to the success of the treatment with this difficult population. Another very powerful and effective treatment approach is emotionally focused therapy (EFT) which emphasizes creating and strengthening emotional bonds between family members or friends. In EFT, the therapist helps individuals identify adaptive and maladaptive relational patterns and develop more open, attuned, responsive, and loving relationships. Finally, a comprehensive, effective research-based program designed for infants and young children is the Circle of Security Intervention used with children and parents who experience attachment difficulties. This approach helps caregivers become more attuned to their child’s emotional needs by building safety in the dyadic experience, as well as a secure base for the child’s exploration. These three approaches offer therapists many tools for addressing the underlying relational disturbance of children suffering from dysregulation.

In treating children with dysregulation, a comprehensive and integrated model of treatment is needed that addresses the combination of emotional and constitutional problems that impact the formation of secure and meaningful relationships. An expanded model of treatment is proposed that includes:

• Sensory integrative therapy techniques that help the child establish a biological sense of safety for social approach and sustaining physical proximity and that prepare the body for social engagement skills including shared attention and facial and gestural communication.

• Skills training that focuses on helping the child to recognize nonverbal communication patterns, learning to stay in the moment while interacting with others, to be nonjudgmental and open in relationships, and to develop an observing ego and capacity for self-reflection.

• Child-centered activity (CCA) that fosters healthy attachments with others that emphasize spontaneous, meaningful interactions with others in both verbal and nonverbal communication patterns.

• Reparenting strategies to provide nurturing and safety in the therapeutic relationship and to help the child and caregivers repair dysfunctional attachments.

Skills training, CCA, and sensory integrative therapy techniques are blended together in treatment with primary emphasis on meeting the immediate needs of children in the interactive pattern—parent and child or other pairings.

In this chapter, this integrative treatment approach is described as it applies to children with dysregulation. The attachment patterns of children with dysregulation are first described and how these may be assessed. Sensory integration therapy techniques are presented first because of their importance in establishing psychophysiological safety and readying the child for social engagement. The elements of skills training are then presented. CCA is discussed in its application to children with emotional dysregulation with a case example. Specific strategies to reparent the parent and child in the context of the therapist–client relationship are presented. Lastly, a case example is presented that incorporates the various elements of the treatment approach.

1. Overall philosophy of treatment

Children who are irritable, anxious, depressed, or volatile can be extremely challenging for family members to live with. Oftentimes family members cope by developing interaction patterns of avoidance, rejection, resistance, or overcontrol. A caregiver who walks on eggshells around their distressed child may find that they retreat or “shrink from interaction” when the child is edgy so as not to “rock the boat.” Or in the case of the highly distractible child with ADHD who seeks constant novelty and stimulation, the whole family may exacerbate the problem by engaging in a steady stream of changing activities, interrupted conversations, and emotional chaos to accommodate the child’s attentional style. There are many maladaptive patterns that can hamper the child’s capacities to engage in healthier relational patterns.

It is important to recognize the stress that coping with a dysregulated child places on the entire family and their relationships with others. Family members may have little reserve for coping with the irritable or depressed child and avoid interacting with them, or they may constantly argue and become entangled in abusive or destructive interactions. Marital tension may be heightened when parents struggle to parent such a child. In some cases, persons living with a dysregulated child may choose to become peripheral to the family, working long hours to avoid a hectic and dysfunctional home life.

A list of underlying assumptions that may be useful in thinking about how one works with individuals with dysregulation and their families, is given as follows.

1. There is no one right way to work with families. There are different styles of interacting, some individuals more verbal than others, and what works for one person may not for another.

2. Understanding development processes, attachment patterns, self-regulation, and the varying constitutional patterns in typical and atypical development is important to the helping relationship. Helping the individual and his family understand the child’s strengths and needs can be very useful in guiding the next steps to help the child achieve emotional well-being.

3. Recognize countertransference—it is very powerful. The feelings and reactions that are elicited in the therapist in working with the child and their family often help in understanding the relational dynamics. The countertransference may reflect feelings that the caregiver and child are projecting into one another that in turn elicits a response in the therapist. The countertransference often provides important insights about the treatment process and what needs to happen next.

4. The parent and child have it within them to find the answers. They need to discover what will work best for them. The relationship of the child with other family members is often one of uncertainty and discovery. It is often hard for professionals to resist a “fix-it” model, but if the parent and child can learn better problem-solving, they will make better use of the therapy.

5. Respect the unconscious and defenses that might be there for the parent and child. Try to get in touch with the feelings that they have about themselves. If an approach does not seem to be working, one may ponder why it is not.

6. Strong feelings should be elicited in a therapist. This is important for empathy. The feelings may be very uncomfortable, such as feeling depleted, rejected, or angry. These feelings may be what the parent or child is experiencing.

In summary, this approach focuses on the child’s presenting concerns and problem of dysregulation, the stresses in the family that might arise because of the child’s difficulties, and adaptive and maladaptive interaction patterns with others.

2. Attachment patterns of children with dysregulation

Addressing the quality of the child’s relationships in their life is vital in therapy. Understanding the different types of attachment patterns in children with dysregulation is useful in guiding this process. Let us first take a look at what happens in an optimal parent–child attachment. When the child feels safe and secure in relationships, they can tolerate the proximity of another and seek comfort when distressed from people who are sensitive, caring, and attuned to their needs. The capacity to seek comfort has a lot to do with the child’s ability to organize movement toward another and to tolerate the sensory components related to physical contact or proximity of another. As they approach others, the child signals their emotional state through eye widening and gaze, facial expressions, head and postural adjustments, listening responses, and prosody of voice. Neural regulation of the polyvagal system assists in mediating social engagement and physical distance with others while also providing a calm, visceral state (vs. a freezing response) (

Porges, 2003). The child can take in other’s attempts to soothe and modulate their internal distress while inhibiting body mobilization responses that cause fight or flight responses. As the child socially approaches, they immobilize without fear, an essential behavior for mating, nursing, and seeking physical comfort. This is regulated by the neuropeptide, oxytocin, which is necessary for the formation of social bonds (

Carter & Keverne, 2002).

Once the child has established a sense of biological safety in the internal and external environment, they need to communicate their needs through both verbal and nonverbal means without overwhelming others. This is accomplished by the social engagement system that controls the upper motor neurons that regulate brainstem nuclei. In an optimally engaged nervous system, there is eyelid opening, mutual gaze, smiling, a relaxed middle ear muscle to allow for listening and orienting to vocal cues, vocal prosody and inflected speech, and head tilting and turning for gestural orientation. There is the processing of other’s affective and social cues, which allows for attunement to what is unspoken between individuals. At the same time, the child is able to receive and integrate feedback and support from others while reciprocating a sense of safety and security. There is a jointly constructed reality between the persons that is mutually experienced as supportive, secure, and safe.

Once the child can organize social engagement and obtain safety and protection from safe, secure persons, they can seek to share and understand others. This latter function relates to the capacity for intersubjectivity. This enables the child to communicate effectively, cooperate, interpret social meanings, and to understand the perspective of others (

Cortina & Liotti, 2010). In a securely attached dyad, there is openness and a nonjudgmental attitude that pervades their interactions. This process allows the dyad to develop insight to the relationship and empathy for one another. As persons reflect upon what they mean to one another, they develop memories of past and present experiences that establish expectations for their future. In the secure attachment, one strives for the following elements:

1. The ability to be open to interactions and to receive and integrate nonjudgmental attention from others while cocreating a good enough relational experience.

2. A state of mindfulness that permits the person to stay present and in the moment as they interact with one another.

3. The ability to embed past and present relational experiences in memory to evoke secure and safe relationships over time.

4. Insight into one’s capacity for attunement to others and self-awareness of relational dynamics.

5. The ability to seek proximity of persons who provide nurturance, protection, security, and safety when the child feels distressed and to internalize their presence when safe persons are not immediately available.

6. The ability to offer comfort, reassurance, and nurturance in a reciprocal relationship with others.

7. The capacity to discriminate and select individuals who reciprocate love, comfort, and safety.

These various elements operate in the secure dyad. The person achieves a mindful awareness of the security and connection between themselves and others. This process is what a therapist hopes to capture and provide in their relationship with the client and to help the client achieve this in important relationships with others. When a child has secure attachments, they usually have good self-esteem, resilience, positive affect toward others, good social competence, and emotionally healthy relationships. For a securely attached caregiver, they are present and insightful, sensitive and flexible in interactions, and they care for their children in similar ways. It is important to note that some individuals who are secure in their attachments have had problematic or painful childhoods, but can maintain close relationships with significant others. These individuals are resilient and have earned secure attachments by seeking healthy relationships throughout their childhood. This resiliency can override the damaging effects of maladaptive caregiving experiences.

In the next section the three types of attachment disorder patterns described by

Bowlby (1982) and further elaborated upon by

Ainsworth (1963),

Brisch (2002), and

Beebe and Lachmann (2014) are reviewed as they pertain to children with disorders of dysregulation. Examples of these patterns will be described.

2.1. Avoidant attachment pattern

The avoidant attachment disorder develops when the child’s attempts for comfort from others go overlooked. The result is they give up on being close to others. Growing up with a dismissive parent who does not comfort the child’s distress can have a profound negative effect on the child’s ability to feel and understand their own emotions. The child with this attachment pattern is usually dismissive of close relationships and has difficulty seeking comfort from others when emotionally distressed. It is as if the child doesn’t think of others as a source of comfort. Most individuals with an avoidant attachment pattern lack flexibility in relationships and are very isolated people. One way that this pattern manifests is in a narcissistic personality disorder when the child acts as if others don’t matter. The child may be sullen and withdrawn, or they may become angry and controlling of others. Whatever maladaptive pattern they adopt, the child does not access others effectively for comfort and security when distressed.

The child with an avoidant attachment disorder may present as if they are very calm in a distressing situation when in fact their internal experience is quite the opposite. Psychophysiological studies show elevated heart rate and cortisol levels in such individuals when they are stressed by separation or loss of the attachment figure (

Spangler & Grossmann, 1993). Over time, the avoidant individual learns to suppress physiological responses related to distress. It doesn’t mean that they don’t feel distress, but it appears that they cannot generate a solution when they feel overwhelmed. As a result, they overregulate their affect to appear as if they are unaffected and are in essence emotionally paralyzed. Hallmarks of the personality of an individual with an avoidant attachment pattern are aversion to physical contact, a brusque, halting, and impersonal relational style, and flat affect which can appear as depression or apathy. Sometimes the adolescent or adult does not remember their childhood and may normalize or overidealize their mother as being “a good mother” when they report early history. However, when probed by the interviewing therapist, the person cannot remember details to support the

view of having a good mother. Others with this pattern who develop insight may report having a mother who was verbally and physically rejecting of them, who was intrusive and overly controlling (

Sroufe, 1996), or who withdrew emotional support when they needed it. Sadly, the individual with this pattern did not get their needs met as a child and then learn to live as if they have none. Some persons develop a sense of self that they are flawed, helpless, and dependent yet they are isolated from others. Another defense may be to view others as weak and flawed and view themselves with inflated self-esteem. When this occurs, they can be rejecting of others, very controlling, and punitive as a way of distancing from closeness.

2.1.1. Example of child with avoidant personality disorder

Jack’s early history was very tumultuous. He lived in a family with alcoholic parents and four older siblings. Incidents of abuse and neglect were reported to child protective services by neighbors and school authorities. Jack’s older brother was removed from the home when Jack was 3 years old, something that troubled him greatly. Shortly after that, his father left the family. When he was 3.5 years of age, Jack ended up being placed in a series of foster homes. During the 2 years that Jack was in foster care, his mother received intensive therapy to help her with her alcohol and drug addiction, support for her underlying depression, and guidance on how to parent her children in healthier ways. During the time that Jack was in foster care, he was shuttled between three different homes because his foster parents could not manage his aggressive behavior. He lashed out at the other foster children, biting and hitting them, and frequently roamed the house, pulling things from drawers and cabinets. Sometimes he regressed to rocking behavior on the floor, humming and grabbing his cheeks to self-soothe.

By the time Jack was 6 years old, he returned to his biological mother and began individual psychotherapy. His therapist noticed that he had very little eye contact and had a very flat, but hostile affect. Attempts to engage him in conversation were met with monosyllabic responses. Sometimes he engaged in inappropriate laughter and thrilled on stories about terrorism and violence. He was consumed with play and drawing pictures about people getting killed or blown up. He played these aggressive stories obsessively and delighted in the violent deaths that he depicted in play or drawings. His therapist found it extremely difficult to tolerate his aggressive discharge, but more so his inability to process any feelings for the victims in his storylines. His aloof, hostile, and aggressive presentation seemed to be his way to prevent connection with others.

After about a year of Jack being in individual therapy, he joined a social skills group that I led. His individual therapist hoped that this might help Jack to build connections with peers and to learn more prosocial behaviors. Jack preferred to play alone in the group setting and often remained on the outskirts of the group. It was very difficult to woo him into group activities. I frequently designed activities that required the boys to work in teams to do things like build a city out of found objects, or construct a story with props about aliens and earthlings. Jack usually stood off by himself, hummed, and remained quiet unless facilitated to join the play. The other kids in the group were quite put off by Jack’s violent talk and hostile demeanor. One boy in particular would confront him by saying things like, “What is the matter with you?! Don’t you care about anybody in this world?!” We did a share time in the group each week when children would bring in an interesting story to report, or would show something they had created. During the share times, Jack would look blankly at the boys. When it was his turn to share, he would reply, “I have nothing to share” even if facilitated with interesting questions to prompt him.

Jack always had a sour look on his face and was very negative about everything, even positive, fun activities. He remained isolated at home and school, preferring to be by himself. He had little sense of humor and remained preoccupied with violence through the school years. When the terrorist attacks of September 11th occurred, he said, “I wish I could have done that—been the one who blew up those buildings.” When his mother or other kids approached him to play, he would respond with “I don’t care if you play with me,” or “I hate you.” The only time that others could engage him in play was when the activities were very concrete and involved watching or enacting crashing of airplanes or cars, or building something and demolishing it at the end.

Jack had all the hallmarks of a child with an avoidant attachment disorder. After almost 6 years of individual and group psychotherapy, Jack began to show some signs of liking one of the boys in the group. He began to imitate him, especially if we played out an elaborate story in role play. This was his only friend in the world, but it occurred within the context of a structured and facilitated group experience. Although Jack never seemed to express an attachment to me as his other therapist, he was agreeable to keep coming to see me over the years and never exhibited any aggressive or hostile gestures toward me. Jack had a very traumatic early history that resulted in him feeling a high level of internal distress, isolation, and abandonment. By creating an emotional shell, he was able to avoid letting others know him and nurture him. His traumatic early beginnings made it difficult for him to socially approach people and to stay in close proximity to others. He was in a constant state of flight and avoidance and only knew how to interact with others briefly in more superficial ways.

2.2. Ambivalent/preoccupied attachment disorder

An ambivalent attachment or preoccupied attachment disorder forms in childhood when the child has a mother who is unpredictable in her availability, not sensitive to the child’s emotional needs, and who discourages the child’s autonomy. Sometimes the mother infantilizes the child and fosters their helplessness. This results in a child who is anxious about their mother’s whereabouts which in turn hampers their ability to explore and develop autonomy. These children tend to be clingy, immature, and hard to soothe, a pattern that can remain throughout life. The child ends up feeling helpless and fearing abandonment.

There are two types of ambivalent/preoccupied attachment disorders: the angry and the passive types. When this pattern manifests in the angry form, the child seeks connection with significant others, then rejects them and becomes angry and hostile. In the passive type, the child is overwhelmed with their own sense of helplessness and cannot approach others for comfort or intimacy. Even in the presence of a nurturing person, they seem to seek a mother figure who isn’t there. This attachment pattern has been linked with histrionic personality disorder (

Schore, 2002). Children with insecure attachment are often dismissive of close relationships and are preoccupied with their own state of mind. Some individuals with this pattern can mirror their own child’s affect, but have no idea what to do with it and quickly feel helpless and overwhelmed. Their own children’s needs can pose a threat to them which sabotages their ability to respond sensitively to them. The end result may be parents and their children who engage more comfortably with the nonhuman world because of their difficulties in interacting sensitively with one another.

When a child has an anxious attachment disorder, they are apt to give and receive mixed emotional messages. Their narratives are tangential and hard to follow. Often they are overly absorbed in their own relationship problems. They tend to be highly vulnerable to distress but can’t come up with solutions to manage it because they are constantly in a state of overwhelm. They hope for closeness from others but fear the loss at the same time.

2.2.1. Example of ambivalent attachment, passive type

By the time Josh was 14 years old, he had suffered a great deal throughout his childhood. His mother who was mentally ill with severe depression left the family when he was 7 years old. She reappeared when Josh was 11 and decided to raise his two younger brothers, leaving Josh to live with his father in an extremely disorderly and cramped apartment. Throughout his early teen years, Josh often had to fend for himself. His father was an alcoholic and had bipolar illness. The father he knew was either rageful and violent toward Josh or he was deeply depressed, immobile, and drunk. Josh was resourceful enough to get to school, feed himself, and take care of his needs. He stayed out of the line of fire with his dad. Josh worked after school making deliveries for a local grocery store, earning enough to pay for his food and other expenses.

Josh frequently had troubles sleeping at night and worried constantly that he would be kidnapped in the middle of the night by someone. He would part the curtains in his bedroom and look out at the street light below, imagining that there was somebody looking up at him from the dark shadows. He sometimes missed his mother, but other times he felt relieved that she was not in his life anymore. When I asked him about his mother, he expressed considerable ambivalence about her, sometimes making it out that she did him a favor by leaving him behind.

Josh remained a loner at school and had no friends to speak of. He was very studious and liked science and math. He was proud of his good grades, but did not care if anybody praised him for his hard work. When he was at home, he spent most of his time playing video games or watching TV. He hated exercise and was becoming quite heavy, in part because of overeating and a poor diet.

Although Josh was very passive about things that upset him, occasionally he would blow up over minor things like if he wanted to eat macaroni and cheese and there was none left in the apartment. Or if his father was driving and he took a wrong turn, Josh would scream at his father for being an idiot. After these irrational outbursts, Josh would act as if everything was fine. Josh was very much like his father who was explosive and judgmental at one end of the spectrum, then at other times, he would look flat, unemotional, and thinking everything would be just fine.

Josh came to therapy between the ages of 12 and 14 years, referred by the counselor at his school. Often Josh would appear for therapy saying he had nothing to discuss, but gradually over the course of the first year, Josh became more available to talking about his relationships with family members. As his depression began to lift, Josh would often well up with tears and say things like, “Nobody takes care of me except for you. My father wants me to take care of him, but I can’t do it.” I would say things like this. “You work very hard at school and the grocery store, but it would help if you could allow your teachers and friends nurture you. When you are flat in your reactions, it’s hard to know that you care or want help. And when you become enraged, it scares other people. It’s like what your father does to you.”

In the upcoming weeks this was our focus. When Josh was kind to his father, his dad didn’t trust it. His father would cringe and freeze up, wary that Josh would either withdraw for hours or end up yelling, slamming a book, or knocking a chair over. Josh couldn’t stand his father’s emotional and physical dependency on him. His father was always resting and Josh felt that he had to do it all. We came up with two plans for Josh. Plan A was when his father felt well enough to participate in home life. Plan B was when his father was unavailable because of his mental illness. I suggested, “Each of you will need to think in the moment. Who is available at this time? How can you solve the situation at hand when you’re a team and when you’re alone.” We proceeded with many of the treatment suggestions described in this chapter, but at the heart of Josh’s conflict was the unresolved attachments that he suffered from. He seemed to oscillate between being angry or passive. In my work with Josh, I tried to function as a guidepost for him to help identify his interactional patterns, his and his father’s responses to one another, and how their sense of selves suffered in the absence of nurturing, validation, and support.

2.3. Disorganized/unresolved attachment disorder

The disorganized or unresolved attachment disorder is common in children whose parents suffered from mental illness, physical and emotional abuse, poverty, or substance abuse. It is typically seen in individuals who have suffered from trauma and loss. This

pattern occurs when the mother is perceived as frightened, but who is also frightening. The child is caught between the urge to approach and avoid the mother’s presence. There is no healthy way to escape and the child disorganizes internally. In essence, there is fright with no solution for the child (

Schore, 2002). In the young child, we see the child backing away from their mother, freezing, seeming dazed, or collapsing to the floor when challenged with a physical separation and reunion. In some children, they develop a pattern of caring for their parent as a solution to the problem. Their parent may welcome this role reversal because it meets their own emotional needs.

In children and adults with disorganized attachment, they can be easily flooded by anything that evokes memories of trauma, loss, and abandonment. They can also be triggered by their own child’s distress which can result in dissociated states, overwhelm, or emotional shutdown. Borderline personality disorder is common among this type of attachment disorder. Their behaviors can be quite unusual or bizarre. For instance, one may see the person give a very detailed account of something distressing, then fall suddenly into a long trance-like silence afterward. When this is pointed out to the person, they may rigidly deny the experience.

2.3.1. Example of child suffering from disorganized attachment disorder

Naomi was 5.5 years old when she first began individual psychotherapy for her attachment disorder. She was adopted from a Russian orphanage at 2 years of age. For the first 6 months that Naomi was with her adoptive family, she had difficulty tolerating being held. She could not bear to sit on a lap or have her hand held when walking outside. By the time she was 3 years old, she would approach her mother and hug her when picked up from preschool. Despite her initial aversions to being touched, Naomi would often, without warning, go up and hug strange men and be overly friendly toward acquaintances. She would sometimes run up to another child’s parent at her preschool, hug them, and ask “Am I going home with you?”. Sometimes she would climb into the lap of a man she didn’t know and hug him.

Naomi had a very strong urge to touch things around her. Going places, such as a store was a nightmare for her parents because she would touch and handle everything in sight. Sometimes Naomi would mouth objects inappropriately, such as putting the ketchup container in her mouth while eating dinner at a restaurant. She often would put her fingers in things that she shouldn’t touch like dipping her fingers in beverages being sold at a fair. Her mother felt like she couldn’t leave Naomi unsupervised for even a few minutes because of these behaviors.

From the time Naomi came to live with her adoptive parents she chewed her finger and toe nails down to the quick so that they often bled. She did the nail biting especially when she lay in bed at night trying to fall asleep or when watching TV. Her parents were also quite concerned about Naomi’s tall tales ranging from things like “I have two cats” when the family had two dogs to “my sister is dead.” Sometimes the tales were quite believable (i.e., “my dog died”), but other times they were quite morbid about persons dying or getting stabbed.

Naomi came to therapy with me for over 10 years and during that time, there were several repeating behaviors, all of which were quite troublesome. She frequently drew obsessive pictures of a girl who she said was herself, then drew dark red scribbles down the middle of her face and said that the girl was bleeding. Or she would draw a heart split in two. By the time she was 8 years old, she began writing and leaving suicidal notes in places like at school and home, and occasionally left them on my desk as she left my therapy room. The messages were things like, “I’m sorry for me living. I hate me. I want to die VERY BADLY so I won’t be a burden anymore. Please someone kill me. I’m already dead inside.” We took these notes seriously, and increased the frequency of her therapy, as well as working with a psychiatrist to get Naomi properly medicated.

Naomi’s play often depicted her death wish as well. Out of the blue she would say things like “A baby is falling and getting hurt,” then she would take a toy gun and suddenly shoot herself and say that she killed herself. A repeating play therapy storyline was that she would flirt with a very bad, evil man who would kidnap her. She would pretend to be held hostage by the man who would threaten her. She wanted me to try to save her from the evil man, but when I succeeded in freeing her from captivity, she would change her mind and wish to stay with him.

This theme of people or animals being both mean and loving at the same time continued in many forms. It could be a pet crocodile who would abuse and bite her, then lick and kiss her back. If I questioned her about why she had a pet crocodile who was mean, she would reply, “I deserve it!” Often Naomi would be very disorganized in these play scenarios, oscillating between wanting safety and protection and abuse and aggression directed at her. The stories almost always ended with Naomi seeking the abuser as the one who nurtured her.

Naomi is an example of a person with disorganized attachment disorder. She suffered emotional abandonment and likely abuse as a young child at the orphanage. These memories were preverbal and as a result, it was very difficult for Naomi to make sense of what happened to her in the first few years of life. She never learned how to self-regulate emotional states. Her way of coping was to flood emotionally, to shutdown or become disorganized in her behavior, or to turn her distress and anguish inward to herself. The moment-to-moment shifts in her behavior and emotional state caused high emotional variability and a lack of internal safety. By the time Naomi was a teenager, she expressed her constant state of distress by cutting herself, indiscriminate relationships with boys, and suicidal threats. However, her long-standing relationship with me served as a secure anchor and she sought emotional comfort and help from me each time she lost internal control. Although her relationship with her parents and sister remained highly conflicted, Naomi had developed a close bond with me and a few close girlfriends.

3. Assessment

The assessment process should include a clinical interview that examines the parent and child’s attachment history and view of important relationships in their lives. This should be accompanied by clinical observations of the child’s gestural/affective display and social engagement. These observations should include evaluation of the child’s ability to form a therapeutic alliance with the therapist. The

Functional Emotional Assessment Scale described in

Chapter 1 can be used as a guideline in observing the child’s attachment behaviors during interactions. Observations of the nature of affective display should include eye gaze, facial affect, vocal inflections, neck and trunk posture, and breathing patterns. These variables reflect the child’s capacity to establish a sense of biological safety.

It is very useful to observe the parent–child relationship using the Strange Situation paradigm detailed in the Circle of Security interactional assessment (

Powell et al., 2014). In this assessment, the parent and child are videotaped to evaluate the dyad’s capacity to engage in reciprocal interactions with one another while the parent provides a safe haven and secure base from which the child can explore the environment. In addition, this chapter ends with an

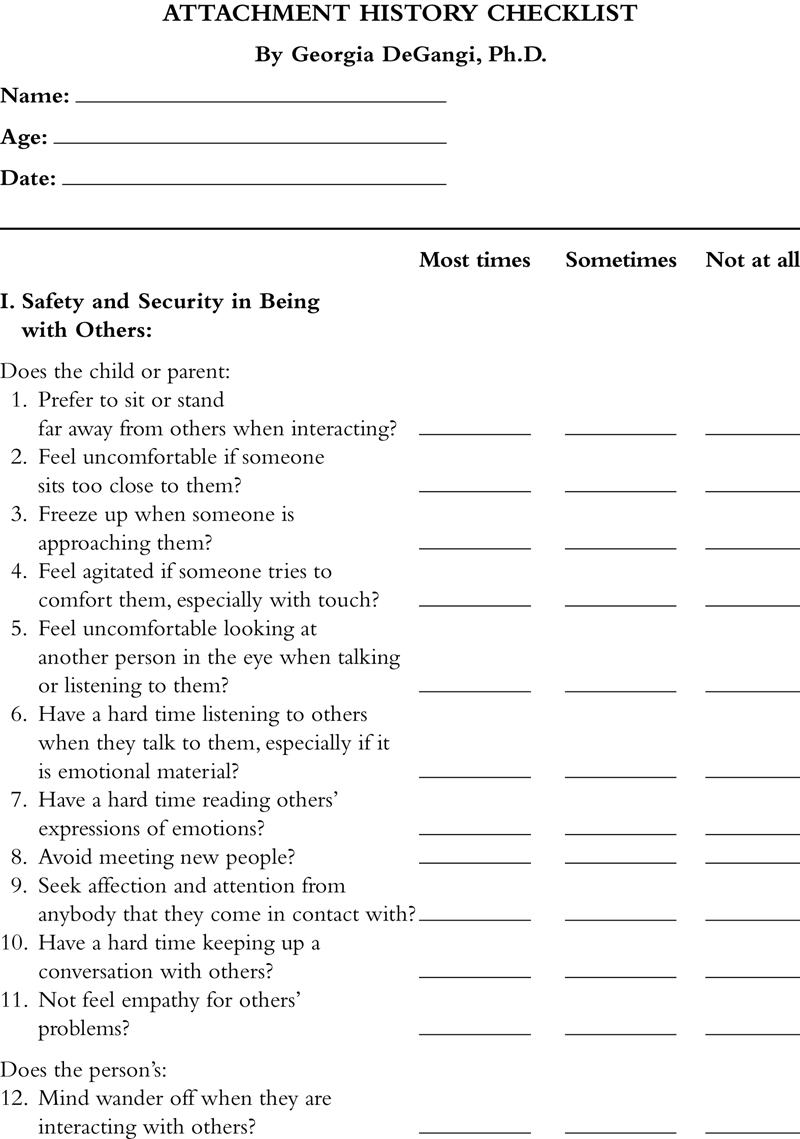

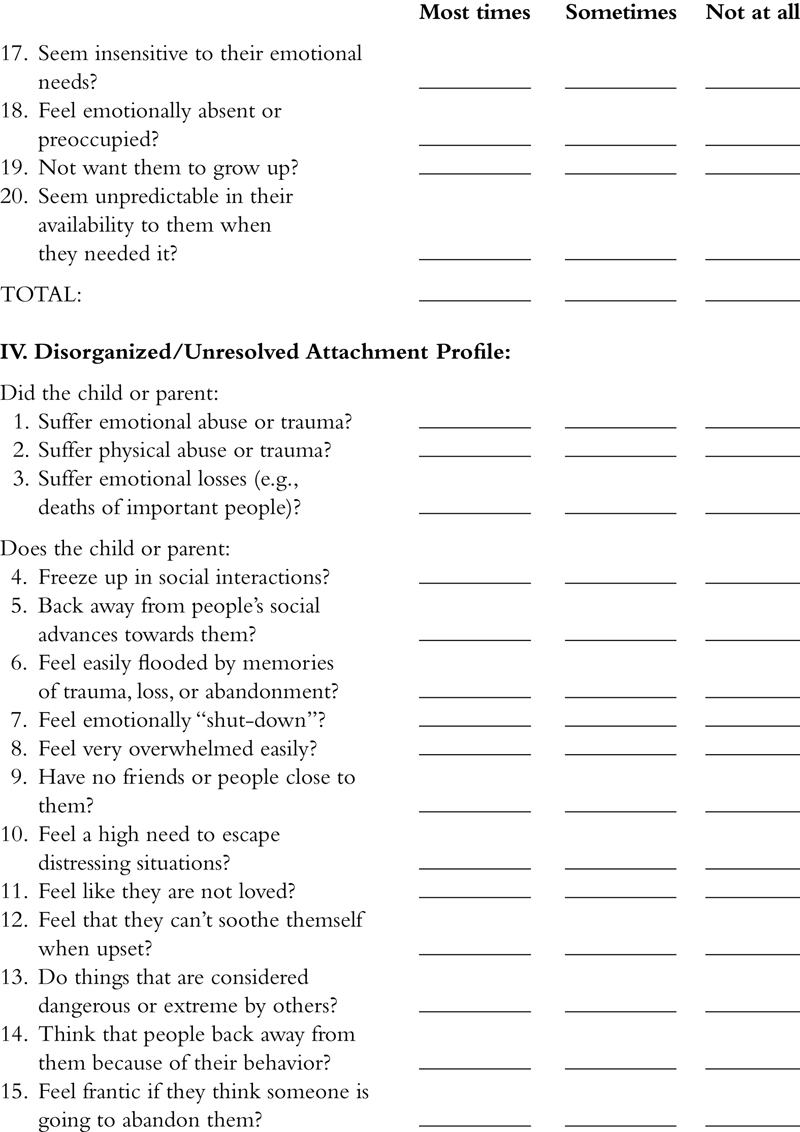

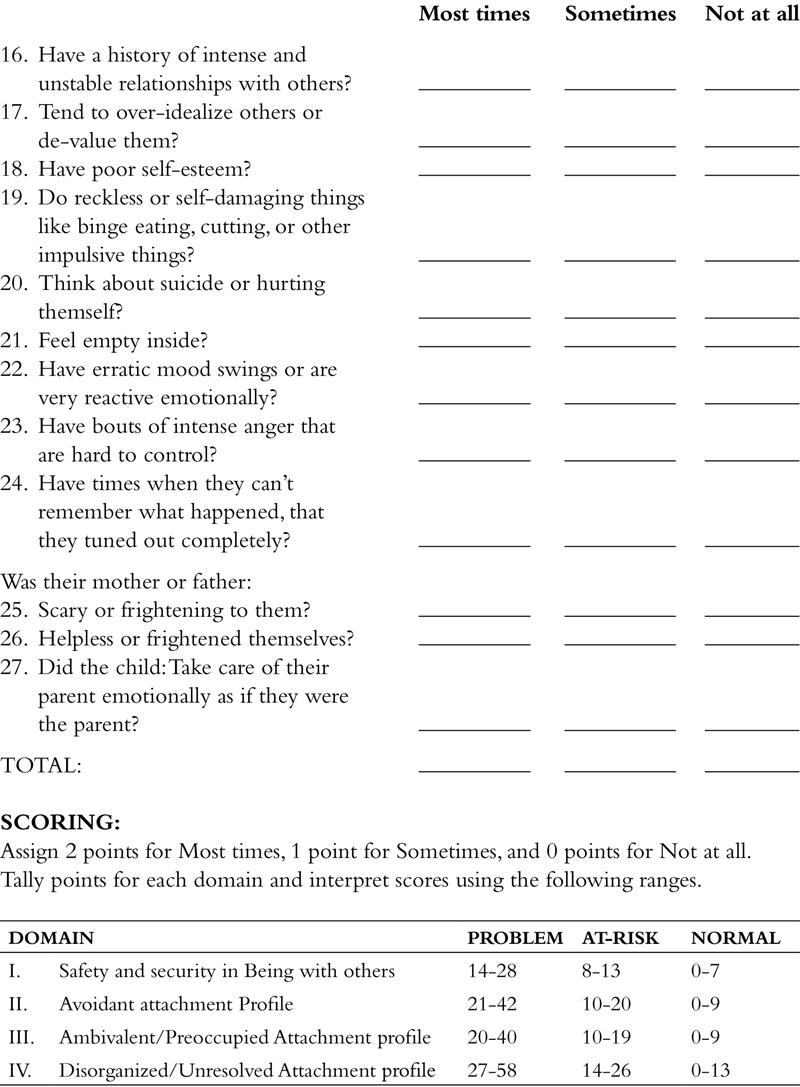

Attachment History Checklist, which can be administered by the therapist to understand the child’s attachment profile.

The Adult Attachment Interview developed by

Main and Goldwyn (1994) is structured as a clinical interview and is helpful in understanding the client’s internal working model of attachment. A modified interview based on the AAI that can be used in a clinical interview with a child who is 11 years or older and/or with the child’s caregiver, is given as follows.

3.1. Clinical interview

These questions can be used with a client when beginning therapy or during the course of treatment. Pay extra attention to affective cues during the interview, such as interrupted eye contact, shifts of affect, and changes in vocal inflection and posture. The coherence of the client’s story and their state of mind while talking can yield important information about attachment history. Importantly, does the client’s narrative hold together? For instance, are the adjectives used to describe caregivers in sync with historical events? Can the client tune into their own experience while communicating their history? The therapist is listening for clarity, relevance, insight, and affective connection with one’s personal history.

1. Tell me about your family growing up. Who was in your family and where did you live?

2. What was your relationship like with your parents, your siblings, and any other significant persons in your family, such as grandparents, aunts or uncles, or nannies?

3. Who raised you? Were they nurturing to you, spending time with you and taking care of you?

4. What five adjectives would you use to describe your mother? What about your father?

5. How has your relationship with your parents changed over time?

6. What is your earliest childhood memory? Are there any notable memories you’d like to share?

7. If you were hurt or upset as a young child, who comforted you and how?

8. Do you remember being separated from your parents? How did you feel? What did your parents do?

9. Did you ever feel rejected as a young child? By whom and what happened?

10. Did you have any significant losses in your childhood (e.g., deaths of important people, illnesses, divorces of parents, moves)? How old were you and how did you feel at the time? What is the effect of these losses on your childhood?

11. How do you feel now when a loss happens to you? Have you had any important losses in your current life (e.g., parents, close friend, pets, and so on)?

12. Have you ever suffered any abuse—emotional or physical? Have there been any traumatic events that have affected you? Is there anything frightening to you in your life now?

13. Do you feel isolated? Who loves you or has loved you in your life?

14. If you could change anything about your past or childhood, what would it be?

15. Where in the world do you feel safest? This can be a real or a fantasy place.

Children with a history of being dismissed and overlooked by their parents often have difficulty constructing a coherent narrative. They may not be truthful and often have little to say about their attachment history. This is often a by-product of the client experiencing a caregiver who could not attune to their desires, needs, or feelings. Clients with a dismissing history often give brief histories and depend upon the therapist to elicit responses from them.

In contrast, children who have preoccupied attachment disorders are often tangential and hard to follow in a clinical interview. They are intensely troubled and overwhelmed with distress which makes it difficult for them to think about how they feel and to gain insight about their past history. Likewise, children who have an unresolved/disorganized attachment disorder may be unable to stay on-topic when discussing their trauma or loss. There may be lapses in their stories and the child may enter into a dissociated state of mind while reflecting on these difficult past events.

3.2. Clinical observations of psychophysiological safety

Since the face and body are important indicators of the child’s psychophysiological safety, the following should be observed in clinical interview and therapy sessions with the child. Keep in mind cultural and developmental differences in interpreting the following.

1. Nature of eye gaze: Can the child sustain eye contact with you while listening and talking? Do the eyes reflect emotions (e.g., eye widening, smile lines, frown, scowl, and so on) or are they motionless?

2. Facial affect: Does the face animate with expressions including the forehead furrowing, eyes crinkling, and cheeks lifting when smiling or is the face flat with little emotional expression?

3. Prosidy: Is the voice animated and inflected or does it lack musicality and inflection?

4. Neck and trunk posture: Does the neck and trunk incline toward you in a natural way as the child engages in conversational discourse or is it stiff or turned in another direction? Is there mirroring of body postures and gestures of you and the child during the interchange (e.g., the child sitting a particular way, the other person does similar pattern)?

5. Breathing pattern: Does the child use shallow, rapid breathing pattern with the upper chest versus deep diaphragmatic breathing? Are the breaths longer on inhalation (seen when the child is trying to activate arousal) or do they seem longer on exhalations (seen when the child is trying to achieve a calm state)?

4. Treatment approaches

A four-tiered treatment model is presented as follows. The first step is to develop biological safety and security to help the child tolerate close proximity with others, to signal others effectively with facial and postural gestures, and to develop social approach without the urge to flee, freeze, or disengage. Skills training focuses on (1) helping the client attune to emotions on a nonverbal and verbal level, (2) to understand unhealthy early and current attachment patterns and develop healthier patterns in their current life, (3) to develop a more secure sense of self, and (4) to create insight without being overwhelmed. CCA is described which focuses on integration of self-regulation and interactive regulation. These enable the child to create and sustain a therapeutic alliance, to become aware of emotions experienced during interactions, and to modulate emotions for more successful relationships with others. Finally, strategies for reparenting the caregiver in the course of therapy are described to provide a reparative experience. A number of Skill Sheets appear in the appendix, which present treatment strategies to address problems of attachment. These include Skill Sheets #10: Finding pleasure and making connections; #11: Creating positive life experiences; #13: Increasing personal effectiveness; #16: Keeping track of positive behaviors; and #20: Communicating effectively with others.

4.1. Developing biological safety and security

In this section, therapeutic techniques are described that can be used to create biological safety for social approach, to improve the capacity to sustain physical proximity to others, and to increase self-awareness of facial and physical gestures during interactions with others. Many of these strategies are drawn from sensory integration therapy.

1. Increase vagal functioning: By increasing vagal tone, the child will feel a greater sense of biological safety and security. This can be accomplished in the following activities:

a. Breathing exercises that emphasize inhalation to the count of 4–5 and long exhalations to the count of 8 or 9. Repeat these at least 8–10 times in a row. Chanting, singing, or playing a wind instrument also create long exhalations.

b. Oral–motor exercises that facilitate sucking or resistive mouth movements, such as drinking through a straw, sucking on a hard candy, or drinking thickened fluids like a milkshake.

c. Linear movement activities including rocking in a rocking chair or a glider chair.

d. Positional changes with the head inverted lower than the body, such as yoga poses (e.g., inverted poses like downward facing dog or the plough) or lying on a foam wedge with the head lower than the pelvis.

e. Weighting the abdomen or lap with a large heavy beanbag or weighted pillow.

f. Creating neutral warmth to the body by wrapping in a soft comforter.

g. The thumb webspace is the acupressure point for heart and lungs. Have an assortment of stress balls handy in a basket near where the client sits for them to manipulate in their hands. Resistive therapy putty can be used to squeeze in the palms. A variety of interesting stress balls are available through

www.abilitations.com.

2. Environmental modifications to create biological safety: Many individuals with attachment disorders or who have experienced trauma are hypersensitive to threatening signals in the environment. Threatening stimuli should be minimized.

a. Low-frequency sounds and ambient vibrations should be minimized if at all possible. If heaters, air-conditioners, and other machinery sound cannot be muffled or diminished, then the child may wear noise-cancelling headphones and sit on dense foam cushions or surfaces that don’t transmit the vibration from these things. White noise machines or oscillating fans can be helpful in screening out these sounds if they can’t be decreased.

b. Create auditory stimuli that provide irregular, soothing input, such as a tape of waterfall sounds or a table water fountain. Playing hemi-sync audiotapes can help decrease awareness of threatening sounds in the environment.

c. Seek physical safety by sitting with their back to the wall or having a physical boundary behind the back, preferably a soft pillow cushioning the back of the chair. Whenever possible, the child should sit in a booth in a restaurant, walk next to buildings on a crowded street, or sit in a corner of the room facing toward the crowd.

3. Decrease hypervigilance: Many children with problems of attachment have hypervigilance. This can also occur in children with ADHD who seek visual novelty.

a. Learn to settle the eyes on neutral visual targets, such as looking at a tree on the horizon, a lava lamp, or moving sand sculpture.

b. When engaging in social interactions, practice looking periodically at soothing visual stimuli, such as goldfish swimming in a small tank, a water fountain, or out the window at nature when the child feels flooded with emotion.

c. The child can fold their arms and apply pressure on the upper arms or on the thumb webspace with one hand to inhibit the urge to look away. Placing the index finger horizontally over the upper lip also calms darting of the eyes.

d. Practice looking at another person’s face without talking. Props, such as humorous hats, eyeglasses, wigs, etc. can be used to do something playful while focusing on eye gaze.

e. The child can try focusing and settling their eyes while looking in a mirror to give themselves visual feedback of what it feels like to hold the eyes steady. This should be accompanied by deep breathing exercises to maintain a sense of calm while steadying the eyes.

4. Increase vocal inflection during conversation: There is often a monotonic quality to the voices of children with attachment disorders or they say everything too loudly or too softly. Learning to modulate vocal quality is helpful to successful interactions.

a. Provide feedback to the child about the quality of their voice when they report something in a flat, monotonic voice and it does not match the emotional content of their conversation.

b. Have the child practice reading emotionally evocative sentences with great animation and inflection, emphasizing integration of body gestures, facial expressions, and vocal prosidy. Look for a match between facial and body cues.

c. If the child has a pet or a sibling at home, they may practice talking to them as if it were an opera, singing out what they wish to say with dramatic physical gestures or communicating messages as if the other person doesn’t understand English.

5. Create more natural physical gestures during conversations: Sometimes there is a freezing of the body, unnatural restlessness, or stiff body postures that don’t reflect emotional availability for social interchange.

a. Relax body rigidity by doing large arm swinging motions in a figure 8 motion in front of the body or by swinging the arms up toward the ceiling, then down toward the knees while dipping the body in line with the motion.

b. Some of the tai chi exercises help to induce a more natural body posture that coordinates with breath space (e.g., relax and sink into gently bent legs while turning at the waist, letting the arms swing naturally).

c. Videotape the child in treatment while talking with the parent or therapist. This can be useful in offering feedback about facial, body posture, vocal and gestural cues. The tape can be watched in treatment with the child to see what they self-observe and to provide them with feedback.

6. Immobilize without fear: This is important for experiencing feelings of love and nurturing.

a. The child may need to learn to stay close without fear, practicing with a family pet, a parent, or other nonthreatening person. Practice deep breathing while engaging in a close, tactile activity (e.g., snuggling and reading a book with a parent, brushing and hugging the dog, or sitting and rocking on a porch swing with a good friend).

b. When interacting with persons that evoke fear, practice safe escapes like taking a break to go to the bathroom, getting something to drink, or taking a short walk.

7. Social approach activities: Some children find the act of approaching others in everyday life very stressful.

a. Engage in social approach activities in neutral situations, such as ushering at a play or church service, handing out leaflets to neighbors, or walking the dog in a park and approaching other dog owners for a greeting.

b. Go to public places like an eatery and practice sitting near strangers, finding ways to stay soothed without wishing to flee (e.g., listen to music on headphones, reading a book).

c. Call a friend or potential friend on the phone and arrange a get-together. Plan an activity that is organizing when meeting them (e.g., walking in the park together, hiking, going to a movie, playing games, or groups like 4-H). Having a mutually appealing topic or activity will provide a reason to stay engaged in social interaction with others.

4.2. Skills training

Skills training for children with dysregulation involves a blend of dialectical behavioral techniques (

Linehan, 1993), techniques to build safety and security within the dyad’s relationship (

Powell et al., 2014), and practical management strategies. When therapy is initiated, the clinician seeks to help the parents and child understand their own behaviors and how others respond to them when behaviors occur. The clinician discusses what techniques have already been tried by the parents in order to determine which ones may or may not have worked. Skills training takes the form of a working dialog with the parent and child to develop the best match between their concerns, the family lifestyle, and management techniques. Major emphasis is placed on developing problem-solving strategies from which the parents and child can develop insights about themselves and their relationships. For example, the mother may realize that she is overcontrolling of her child to avoid the child’s behavioral outbursts. It is important to help such persons understand what underlies their inability to share control and develop strategies to self-organize.

In the therapy process, the therapist should recognize nonverbal communication between themselves and the parents and child. Since all communication is a conversation between one person to another, the therapist should pay careful attention to somatic experiences in their own body that might be communicated by the client. For example, if the therapist feels a sudden choking feeling in her throat that is not commonly experienced, what emotions are being choked off by the client? Or if the therapist suddenly feels sleepy in the session, are they attuning to a feeling of deadness or dissociation in the client? When the therapist perceives emotions of their client, they often feel the emotions themselves.

The techniques described in the Circle of Security Intervention (

Powell et al., 2014) are especially helpful in addressing the needs of infants and young children and their caregivers. This intervention focuses on helping the caregiver to build positive intentional

responses toward their child while also developing the capacity for reflective functioning to provide regulated parental affect, “good enough” parenting, and a secure attachment base. The Circle of Security Intervention is a 20-week program that emphasizes how to create a holding environment between caregiver and child and to develop safety and security in the relationship to support the child’s exploration. Through psychoeducation and practice, caregivers learn about their child’s affect regulation, how to read and respond to their child’s cues, and how to respond positively when ruptures occur in the relationship.

It is also important for the therapist to be aware of enactments of early experiences that might occur within the therapist–client relationship. These are usually expressions of unconscious vulnerabilities of the client. Who is the therapist to the parent and child and who are they to each other? For example, a parent may complain that the therapist is too nurturing and wish for them to be stoic to protect them from emotional loss and to distance themselves from closeness toward the therapist.

The following strategies can be used in treatment to develop better attachment capacities and awareness of current and past relationships.

1. Develop awareness of here and now moments: Mindfulness exercises are especially helpful to be attuned to the person’s state of mind in the moment. Practice a short meditation activity in the session that focuses on stilling the body and the mind. By focusing on the internal breath space, a simple visual or auditory phenomenon, or a visualization exercise (e.g., scene at the beach), the mind is settled. An openness is created for awareness from one moment to the next. Following this, the client should be encouraged to express himself, letting the mind roam freely to whatever comes to mind in that moment. The therapist should highlight the child’s awareness of “now” moments versus “then” and what insights the client is having right now, disentangling past emotions from the present, and creating a new way of being present in interactions with others.

2. Learn to be present in the moment without judging it: Create an open mind to oneself and others. This is very powerful in repairing relationships and in developing healthy ones. Practice nonjudgmental awareness in therapy between family members and between the therapist and child. Modeling a nonjudgmental stance to the parent and child is very effective in helping achieve an openness in the therapy relationship. When the client expresses a concern that is laden with “they should or shouldn’t,” the therapist may pause the story and inquire if they can think of another way to view what happened without judging it.

3. Recognize internal emotional states that block or interfere with self-awareness and empathy of others: Label the parent and child’s affective states to help them recognize and integrate their emotional states. Pay close attention to the interaction of somatic and emotional displays (e.g., body is freezing into stillness while child talks about being rejected). Put the experience into words to make the implicit explicit. The therapist should help the parent and child think through how they feel in the past and present. The client should be encouraged to talk about what they want to have happen and how they understand their feelings, others’ responses, and the situation. It is also very helpful to help the client think about their experiences without being flooded with emotions. Encourage self-reflection of the emotional experience and help the client express it and understand it.

4. Focus on developing emotional intimacy with others: Highlight the nature of current and past relationships. Is the parent or child too self-reliant and insulates themselves from others? Do they overestimate their abilities and detach from seeking support? Do they reject others reaching out to them or not allow others to love and support them? Before one can make in-roads into giving and receiving love and fulfillment in relationships, the child needs to trust others to be intimate with them. The therapist must matter to the client and that relationship is one that can be spoken about and understood, as well as other primary relationships (e.g., parents and their children, and friends). The focus of treatment should be on observing internal emotional states and nonverbal behaviors, seeking to understand their meanings. This self-awareness can help the parent or child get in touch with issues of loss, abandonment, insecurities, and fears that fuel emotional distress. If they can identify the emotional and interactive cycle that they are stuck in and learn to tolerate the level of distress they experience, they can find ways to engage more deeply in interactions with others. A key to this process in therapy is to slow down the interactions, focusing on nonverbal communications and their meanings. The therapist needs to sit with the client’s distress, validate it, and empathize with strong emotions that underlie the distress (e.g., isolation, rejection, feeling invisible, and so on). By tolerating the parent and child’s distress and reflecting upon it, the therapist mirrors the internal process that the client must do for himself. The therapist tracks and reflects the client’s emotional states and through this process, there is a deepening of connection.

5. Understand maladaptive attachment patterns and foster healthier relationships: Develop an increasing awareness of the client’s relational style with significant persons in their life. This helps in making the change toward healthier patterns of interacting. If at all possible, this should be done in the context of relational experiences that occur in therapy or are attended to outside of the therapy session. Key interactions are restructured by using specific interventions that help facilitate change. The first step is helping the parent or child observe and identify the patterns that they use. Here are some possible observations that might be highlighted in treatment:

a. Does the person set up situations whereby they abandon others or others abandon them?

b. Does the fear of loss cause the person to back away from emotional intimacy?

c. Does the person isolate from others and prefer aloneness to prevent closeness to others?

d. Does the person reject others and devalue them?

e. Does the client feel rejected and inadequate, unworthy of being loved?

f. Can the person count on others to be available to them for their emotional needs? Do they feel supported and cared for?

g. Does the person feel that nobody thinks about them, that they are unimportant, overlooked, invisible, or dispensable?

h. Does the client signal others that they need affection and love?

Once healthy and maladaptive patterns of interacting are identified, the client is then helped to create new interactive experiences that focus on healthy verbal and nonverbal interactions. The focus should be on the underlying emotions that derail attachment to others (

Wallin, 2007). Central to these approaches is helping the client create a new positive cycle of engagement with others, and to create a new narrative or experiential base for the relationship. Often this requires the child to experience less emotional distress while maintaining emotional engagement with others. This is the key to building an attachment base.

6. Repairing destructive relationships and moving toward healthy attachments: Individuals who have experienced trauma, abuse, or neglect may need to achieve a place of radical acceptance of their past before they can experience healthier relationships. It is very helpful for the therapist to identify specific negative cognitions that the person holds related to these past events (e.g., I am helpless, I am worthless, I am not in control, and so on). The person may need to be guided on ways to create emotional boundaries from individuals who derail their emotional well-being. This involves a process of letting go that those individuals may not be ones who can provide emotional intimacy. Drawing from DBT therapy, the therapist may seek to help the client to engage in the skill of Opposite Action. If they traditionally disengage from others, they may instead focus on ways to engage that feel safe (e.g., nonverbal modes of expression). Or if the child constantly rejects others in his life, the focus is on learning to let in and accept what others give to him. As the parent and child seek to repair dysfunctional relational patterns and relationships, journaling is often a very useful exercise to help them develop an observing ego during the process.

4.3. Child-centered activity

Addressing the attachment capacities and stability of close relationships that exist for the child with dysregulation is central for treatment. CCA focuses on using the inner resources of the child. It is an experiential model focusing on the dynamics of interactions with significant others. It is best to work with both parent and child in session to focus on relational dynamics that underscore their attachment. Applying this form of treatment between a parent and child and any other significant person in the child’s life can be very powerful in restoring and repairing problems of attachment. At the heart of this treatment is helping the parent to be present in the moment with their child,

to read and give effective gestural, vocal, and affective signals, to listen and take in what the child evokes in a nonjudgmental way, and to feel pleasure in a secure, safe relationship with one another. When using CCA with a child, two frameworks are particularly helpful in guiding the process. These include ego psychology as described by

Greenspan (1989,

1997) and an object relations theoretical framework (

Winnicott, 1960). In this approach, the focus is on the dynamics of the parent–child interactions, insights gained by the parent about their relationship with their child, and understanding issues from their past that impact current relationships.

The CCA focuses on improving the child’s developmental capacities within the context of the parent–child relationship or other significant relationships. Relevant stages of emotional development outlined by

Greenspan (1989,

1997) are used to help guide this process. These stages include: engagement and disengagement with objects and children; organized, intentional signaling and communication on verbal and gestural levels; representational elaboration of shared meanings; and symbolic differentiation of affective-thematic experiences. Constitutional problems of the child, such as high irritability, sensory hypersensitivities, inattention, and other problems of self-regulation are addressed by modifying the environment, selection of activity or interactive medium, and highlighting ways of modifying nonverbal or verbal communications so that they are better processed by the child. Insights gained about the parent’s relationship with their child and issues from their own past are addressed as they pertain to fostering healthy attachment patterns and regulatory capacities.

Others have applied principles of infant psychotherapy to the sensorimotor phase of development as well (

Ostrov, Dowling, Wesner, & Johnson, 1982;

Mahrer, Levinson, & Fine, 1976).

Wesner, Dowling, and Johnson (1982) have described an approach that is similar to Greenspan’s “floor time” which they term “Watch, Wait, and Wonder.” In this approach, the infant initiates all interactions and the parent seeks to discover what it is that his or her child is seeking and needing from them and the environment. In this process, the parent may become attuned to her child’s constitutional and emotional needs, how her child wishes to communicate and interact, as well as the quality of the parent–child relationship. Helping the parent to recognize their projective identifications with their child is considered an important aspect of the treatment process. The WWW approach has been used successfully with mentally retarded and developmentally delayed children (

Mahoney, 1988;

Mahoney & Powell, 1988). It has also been used as a method to focus on unresolved relational conflicts of the mother involving the mother’s projective identification with her infant (

Muir, 1992).

In CCA, the caregiver is taught to engage in daily 15–20 minute sessions of focused, nonjudgmental attention with their child. The child is the initiator of all play and the parent is the interested observer and facilitator, elaborating and expanding upon the child’s own activity in whatever way the child seeks or needs from the parent (e.g., to imitate, admire, or facilitate). If the child is older, the parent and child decide together on

a mutually rewarding context for the activity (e.g., making a craft together, walking and talking, writing poetry and sharing it, and so on). The goal is for the parent to learn to be nonintrusive and nondirective in his or her interactions with the child or other child. It is useful for the caregiver to be instructed to “watch, wait, and wonder” what the child is seeking and needing from them, then to respond accordingly (

Wesner et al., 1982).

During therapy sessions, CCA may be practiced for 20 minutes with a caregiver and their child, followed by a discussion between therapist and parent about the process. The caregiver may be asked what they observed about themselves and the child, and what it was like for them to interact in a nonjudgmental way. The therapist’s role is supportive while seeking to help clarify and reflect on the parent’s responses to the child and what the other child’s behaviors might serve for them. This process is important in order to address how a parent might have adapted to the child’s regulatory problems and to help the parent and child become more aware of how their cues might be perceived by others. Parental stress, depression, feelings of incompetence or displeasure with the relationship, connections with the past (e.g., how parented), feelings elicited by the child’s behavior, and family dynamics may be topics that emerge.

Unlike skills training or cognitive–behavioral approaches, CCA is a process-oriented model rather than a technique to be mastered. Some people need considerable help to allow others to take the lead in interactions or, the reverse, becoming active enough in the interaction to be reciprocal. The underpinnings of this approach lie in the view that interactions between children whether they are leisure activities, play, affectionate gestures, nonverbal communication, or a conversation is the medium emotional connections are made.

4.3.1. Goals of CCA

The ultimate goals of the CCA for the child are to:

• Provide the child with focused, nonjudgmental attention from the parent,

• Facilitate self-initiation and problem-solving by the child,

• Develop intentionality, motivation, curiosity, and exploration,

• Promote sustained and focused attention,

• Refine the child’s signal giving,

• Enhance mastery of sensorimotor developmental challenges through the context of play,

• Broaden the repertoire of parent–infant interactions,

• Develop a secure and joyful attachment between parent and child,

• Enhance flexibility and range in interactive capacities.

The goals for a parent are to:

• Develop better signal reading of their child’s cues and needs,

• Become more responsive or attuned to their child, allowing him to take the lead in the interaction,

• Develop a sense of parental competence as a facilitator rather than a director of their child’s activity,

• Take pleasure in their child in a totally nonprohibitive setting,

• Appreciate their child’s intrinsic drive for mastery and the various ways in which it is manifested,

• Change the parent’s internal representation of himself/herself and the child to that of a competent parent and a competent child.

4.3.2. Instructions for CCA

Some instructions that a therapist may use in guiding a parent to learn CCA, are given as follows.

____________________________________________________________________

4.3.2.1. Instructions for child-centered activity

1. Set aside 20 minutes per day when there are no interruptions. Be sure to engage in the activity or conversation during a time when you and your child are well rested and you don’t have other things to worry about like something cooking on the stove or the doorbell ringing. Take the telephone off the hook or put the answering machine on. Be sure that everyone’s physical needs are met, such as toileting, feeding, etc. so that you won’t need to stop the interaction to take care of these needs. Put things out of reach that you don’t want your child playing with (e.g., business papers, fragile objects). Use an area that is child proof where there are no prohibitions or limits that you might have to set.

2. If doing this with a young child, put out two sets of toys so that you can join in play with your child (i.e., two toy telephones, several trucks and blocks). Select toys that allow your child to explore and try new things that are more open-ended in nature. Avoid toys that require teaching or that are highly structured like board games, puzzles, or coloring.

3. Let your child know that he or she is getting “special time” with you. Get on the floor with your child unless you are uncomfortable getting up and down off the floor. Try to stay close to your child so that he or she can see your face and you can see what he or she is doing.

4. If you are often highly directive of others, practice letting your child take the lead and initiate what happens. Interact with your child however she or he wants to engage. Discover what she or he wants from you during this time. Does he/she want you to admire him/her? To listen and be calm? Try out what you think he/she wants from you and watch his/her reaction. See if your child starts to notice you and begin to interact more. Respond to what they are doing, but don’t take over the play or conversation.

5. “Watch, wait, and wonder” what your child is doing during the interaction. Think about what they are getting out of doing a particular activity. Enter their world and reflect on what their experience of it and you might be. Observing others is the first step to providing a foundation of good listening.

6. Watch what your child seeks in their time with you and try to suggest ideas that allow for those kinds of interactions. For example, if your child likes to bang and push toys, pick things that are OK to bang and push. If your child wants to walk and talk, suggest a new park to try.

7. When doing CCA with your child, talk with him about what he’s doing without leading the play or guiding what should happen next. For example, you may describe what she did (“What a big bounce you made with that ball. Look how you like to run!”). With older children, you can ask questions about what is happening (i.e., “How come the baby doll is crying? What is the monster thinking of doing now?”) It’s useful to help your child bridge play ideas, particularly if your child does something, then moves onto the next play topic, leaving a play idea hanging. (i.e., “What happened to the dinosaur? I thought he wanted some food to eat.”). When interacting with a teen, think of ways to elaborate on their conversational topic, activity, or task (“I’m enjoying hearing about this. Tell me more.” “What were you thinking about when that happened?”).

8. Have fun! This is very important! Try to enjoy being with your child during “special time.” If you find it boring, find the balance that will make it fun and interesting for both of you.

9. Remember that “special time” is not a teaching time, planning time, or chore activity. Try to avoid praising your child or setting limits while you play. You want the motivation and pleasure of doing things together to come from you and your child. There is no right or wrong way to play or interact.

10. Sometimes CCA elicits uncomfortable feelings or strong reactions in children. Reflect on what it elicits in yourself. These reactions are useful to talk about with your therapist to understand what they mean for you and your relationships with others. Should you feel overwhelmed by feelings, try to be less involved and play the role of the interested observer. You may want to even take notes on what you notice and shorten the time to 5–10 minutes if that is all you feel you can do. The important thing is that you are giving and receiving focused, nonjudgmental attention and the joy of interacting with one another.

11. Try to do “special time” every day, particularly during times when there are other stressors in your life. Take at least 20 minutes per day for yourself to rest, relax, and do something just for you. Things like catching up on household chores, food shopping, and other work don’t count as time. This is your time to restore yourself.

4.3.3. The process of therapy

CCA is an experiential, process-oriented approach that involves an element of discovery about the parent and child and their relationship. It is often a difficult approach for clients and therapists to learn and do well. When the therapy is begun, the first few sessions should focus on the here and now, that is, what was noticed by the parent about themselves and their child and how they interact rather than how the person felt about the experience. The therapist should avoid trying to coach too much while the caregiver is learning the approach, thus allowing them to find the way that they interact best with their child and to validate that their way of interacting is unique. The caregiver should be guided to take the role of the interested observer in the first few sessions to help them to become more attuned to what the child is seeking and needing. The directive to “watch, wait, and wonder” what the child is doing is often useful. Some parents report that they feel relieved that they do not have to constantly prompt or organize for their child. Through this model of discovering what will help both parent and child, the child gradually learns how to problem solve and stay in the moment, thus deepening engagement and connection.

4.3.4. Role of therapist in CCA

The role of the therapist is one of facilitator of the parent–child relationship by taking on the role of an observing ego. Although the therapist’s role varies depending upon what each dyad or family brings to the process, the therapist should try to avoid teaching or directing the process that occurs during CCA. However, there are instances when the therapist needs to coach, reassure the parent, or modify the approach to be most effective. When a parent has difficulty allowing their child to take the lead or they are overstimulating (e.g., too verbal, too active, or anticontingent), the therapist may need to help the parent tune into the child’s cues. In such cases, the therapist may cue them by saying things, such as “Let’s see what she’s talking about here.”

4.3.5. Debriefing about the process

In the first few sessions, it is often useful to ask the parent questions about their experience of CCA. Some questions that may be useful are: “What have you noticed this week?” “How did you feel when you and your child were doing x together?” “How easy or difficult was it for you to engage in play/conversation with your child?” As the parent becomes more comfortable with the process and in talking with the therapist about their reactions, feelings and projections from the past may be further explored. The therapist may ask things, such as “How did you play as a child with your parents?” “Does playing with your child remind you in any way of your experiences with your own parents?” “Does when you try to engage with your child and she pulls away remind you of anything from your past?” It is not necessary that the parent make connections with their own past or the feelings that are elicited in them in order for the CCA to be successful, although insights are useful to the process. As the therapy process unfolds, the client may talk more about the observations that they made as they did the CCA. They may also discuss how they might have been surprised by their child’s responses, doing something quite different than they had expected.

It is important to avoid overintellectualizing the CCA, focusing too much on questions about why someone did something or asking the caregiver too many questions about what happened. The parent may express emotions, such as feeling rejected by their child if he or she turns their back to them or didn’t listen. The therapist may normalize those feelings by expressing that many parents feel as they do when similar things happen. Empathizing with their position in a nonjudgmental way is very important.