The future of business process management

Keywords

Change; Measures; Process alignment; Process diagrams; Systems; Process maturity gap

This book was written to provide today’s business managers and process practitioners with an overview of the concepts and best practices available to them. We have tried to cover the wide variety and the complexity of today’s business process work. In the last chapter I suggested one direction that I think process work will take in the near future. It will incorporate AI and use it to automate business processes far beyond what we have achieved to date. In this chapter I want to extend my overview of future developments in process work and then reiterate the major themes of this book.

I opened the book by saying: We live in a world that changes faster all the time. In 1968, when I first became involved in business process improvement, computers were nowhere to be seen. They existed and were being used in many businesses, but they were being used in air-conditioned rooms well hidden from most employees. When people came to the company I worked for and asked us to help them improve their processes they invariably referred to problems that involved employees. Since then much has changed. In the 1970s computers became much more common. In the 1980s personal computers were introduced. In the 1990s the Internet became popular and the Web became a part of our culture. Computers began to switch from being business machines to being at the heart of our communications network. Hammer and Champy wrote their well-received book, Reengineering the Corporation, and argued that up until then companies had only really used computers to solve specific problems—automation had been used to pave existing cow paths. In the 1990s they argued it was time to rip out whole areas of the business, rethink how work could be done when computers were used effectively, and create new business processes that would function as superhighways. From the 1990s on computer automation in one form or another has been relentless. Some would cite failures resulting from reengineering. Some companies tried to move too fast and attempt things for which the technology was insufficiently mature. There is always a lag between when a new idea gets a lot of attention and when companies figure out how to effectively implement the new idea.

In spite of problems and occasional backsliding the reengineering idea took hold. Computers moved from a support function to become the essence of every organization’s strategy.

Today one popular cry is for digital transformation. In a sense it’s just another term for business process change or for reengineering, but let’s ignore the jargon and focus on what underlies it.

Amazon.com was formed in 1994 by Jeff Bezos in Seattle (Washington). He has described in several interviews how he sat down with some friends, speculated on how things were going to be sold over the newly popular Web, and wondered what product would be good to sell online. After considering several possibilities, each with their advantages and disadvantages, he settled on selling books. In essence, Amazon created a website where users could come, browse through all the available books, choose one or more, and have it sent to their home. Customers set up a credit card account with Amazon and any books they bought were charged to their cards. Because there were no tax requirements for online sales in 1994 Amazon customers got the book at a discount, which Amazon provided, and without tax constituting a saving even after they paid a shipping fee. Over the course of time Amazon moved from ordering books from a publisher after the customer ordered them to setting up warehouses to stock all popular books. In addition, using their rapidly expanding database, once a customer chose a book Amazon provided the customers with information about other books that customers who bought that book had also purchased. They also offered to send customers emails when a favorite author published a new book. Amazon became a rapid sensation and the poster child for web business.

Amazon didn’t have local stores, or the expense or overhead associated with local stores. They did have a warehouse, and then a few warehouses, but these were very large structures and very efficiently run. Robots were used to find and bring books to shipping clerks. Deals were cut with the US Postal Service and package delivery services to keep their delivery costs to a minimum.

I love to read mystery novels. I’m often told of series I should check out. I used to go to a local bookstore and find that the store had the fifth volume in the recommended series, the volume that had just been published. But I wanted to start the series at the beginning, with a book that had been published 5 years ago. The book store was happy to order it from the publisher, but it was an inefficient process that invariably took a month or more. Then I discovered Amazon. I went online, typed in the author’s name, and got a list of all the books he or she had ever written. Some of the older books might not be in print, but Amazon had deals with used book stores, and they listed used books as well as books in print. I could easily find the first volume in the series, new or used, and order it. Later, if I liked the author, I could go back and order the next in the series or more likely the next two or three. No physical book store could compete with the service Amazon offered—no store was big enough to stock all the books published in the last several years. Amazon was. Amazon seemed to understand my needs as a reader, their interface was easy to use, they often suggested additional books that I ended up buying, and so forth. Amazon completely changed the process that I as a customer went through when I purchased a book. They made the process much easier and I in turn have been purchasing more books from them ever since.

Amazon revolutionized book buying by using the Web to create a new customer interface. They used shipping services to deliver books to my home. Moreover, they offered lots of other services that made my life as a reader more convenient. Once Amazon began several other companies tried to compete. In some cases bookstore chains offered an online service. In other cases publishers tried to use the Web to sell direct to customers. None came close to making the overall experience as convenient as Amazon. Another company with a better interface or better service might have given Amazon competition—there have been many instances in which the first company to offer a service is shoved aside by a later entry that offers a better service, but it didn’t happen in Amazon’s case. Within a few years Amazon completely revolutionized the publishing industry. In effect, they used a digital business model to transform an industry.

Amazon didn’t rest on its laurels. It introduced a handheld computer that a user could use to read a book that they downloaded from Amazon. In essence, Amazon introduced the idea of digital books, and began to encourage authors to write books that Amazon could publish in digital form. Within a short time most publishers found that they needed to publish both paperback and digital versions of all their popular books. Initially, I didn’t like reading digital books. But I travel quite a bit, and I read on the plane and in airports where I often have to wait between flights. Using my Kindle I could download a dozen books to one light handheld computer and be assured that I had enough books to last through a week of travel. Formerly, I had stuffed a half dozen books into my briefcase—now I just bring along my Kindle.

Amazon proceeded from books to almost everything else you can imagine buying in a store, including groceries. One went to the Amazon site with which one was already familiar, and where one already had an account and proceeded to enter a generic name for an item you wanted—say, picture hanging hooks. Rather than going online to find a store that sold them, Amazon presented lots of choices side by side and allowed you to choose. Your choice would invariably arrive in a few days.

Today Amazon is regarded as a generic retail platform. That means that anyone who wants to sell products in an advanced market like the United States will want to make their products available via Amazon’s website because a growing number of items are being sold that way. Why would I want to go to a website run by a picture hanging hook company, figure out how to use their website, establish a credit relationship with them, and so forth, just to make a two-dollar purchase. Instead I go to Amazon, find and buy the item in minutes, and move on to other tasks. I’ve had problems with items I ordered from Amazon, but Amazon has always been very quick to provide solutions. Amazon hasn’t just revolutionized publishing and bookselling worldwide. They are now in the process of revolutionizing retail selling. Bookstores began to disappear in the early years of this millennium. More recently, major retail stores are disappearing, and lots more will disappear in the near future. Large suburban shopping centers can no longer lease all their stores. The world of retail sales has been completely transformed.

Let’s consider another example. Netflix was founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph, two guys from Silicon Valley. The company was founded to let users order DVDs online. The company would let the users choose one or more movies listed on their website, and then ship the DVD to the customer. When the customer was done he would ship back one DVD and another would be provided. This approach evolved dramatically in 2007 when the company began to provide a streaming service that made the movies available on the user’s TV set. Customers could now sit in front of their TV sets and download any movie they wanted. Each customer paid a monthly fee charged in just the same way as one pays for other utilities. Note that whether Netflix sells DVDs or downloads movies to your TV they still need to pay a fee to the owner of the movie. However, since Netflix was popular and producers wanted to sell their movies they were happy to work out a deal with Netflix to offer movies at a reasonable price.

In 2012 Netflix offered its first Netflix-produced TV series and has gone on to produce a variety of series and movies. In 2018 Netflix produced 80 feature films and plans to spend over $12 billion dollars this year producing content. One-fourth of that amount would make Netflix larger than any Hollywood studio, or BBC’s movie unit. Netflix is currently the largest entertainment content producer in the world. It has completely revolutionized the movie, TV, and entertainment industries.

Netflix started by focusing on how it could provide a better customer experience for those who wanted to see a movie. Its initial competition were stores that customers would visit to rent DVDs. Like booksellers, DVD stores were always limited in the movies they could stock. Using the Web, Netflix made it easy for customers to find movies they wanted and to arrange for them to be delivered to their homes. Being able to operate out of a huge centralized warehouse they could provide movies that weren’t always available at stores. When they introduced streaming they went further and eliminated the need to shop on the Internet. One could look for movies and order them while sitting in front of one’s TV—and then one could watch the movie. Obviously, other streaming services sought to compete—Amazon, for example, is offering its own service. To date, however, Netflix’s interface has proven satisfactory and its fresh content is increasingly adding a real plus that customers apparently enjoy.

It’s worth noting that Netflix is a truly worldwide service provider. Not only does it provide film content around the world, but it also has its films dubbed in a variety of languages to satisfy its worldwide audience. Netflix has effected a digital transformation of the movie and TV industries.

Most people think of Apple as a computer manufacturer. They created one of the first personal computers, the Apple, and then went on to create the first commercial computer with a graphic interface, the Macintosh. They also created one of the first handheld flatscreen computers, and later the iPad. They also created the first smartphone, the iPhone. It’s easy to think of the iPhone as a phone, but it’s really a lot more—it’s a small handheld computer. Today the majority of the world’s population access the Internet and Web by means of a smartphone. There were digital cameras before the iPhone, but Apple’s phone made phone photography ubiquitous. Since the introduction of the iPhone, Kodak, the world’s largest manufacturer of film and photographic papers, has gone bankrupt and the photographic industry has been utterly transformed.

Now let’s briefly consider another new company, Uber Technologies, which was founded in San Francisco in 2009 by Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp. The core of Uber’s business is an application that runs on a smartphone. Using the application a customer can call for a taxi. The application uses the phone’s GPS to locate the customer and it uses the GPS locations of available taxis to plot them on a map, identifies the closest available taxi, and routes it to the customer. Often the customer is already a member of Uber and thus Uber has the customer’s credit card information. The application sends a photo of the taxi driver so the customer will be able to identify the driver when he or she arrives. When the cab comes the customer gets in, rides to a desired location, and gets out. The financial transaction is automatically handled via the customer’s credit card.

The smartphone is the platform in this case, and Uber is the application that links customers to available cabs. The interface is very nice and easy to use. The whole process has been well thought out and is very convenient. Uber caught on quickly and now operates in some 600 cities throughout the world. Uber relied on digital technology to transform the taxi business. Their approach makes it easy for smartphone users to get cabs. They have met stiff resistance from traditional taxi companies, but seem destined to transform the taxi industry.

Uber has been investing a lot of its profits in developing self-driving cars, and eventually hopes to provide self-driving taxis to complement its smartphone application. That really will revolutionize the taxi business.

We could go on and discuss several other businesses that have transformed whole industries. In each case a few things stand out. Such companies focus on the customer’s experience (what we called the customer’s process in Chapter 9). In essence, the company figured out how to redesign the customer’s process to make it easier and often reduced the price the customer paid. Second, the company supported the new customer experience with a website or other interface, and used computer technology to automate their back office operations. Put a bit differently, the company created a “platform” or site where the customer could go to find what he or she wanted, order a service, deal with problems, and get various kinds of information. Once the platform was established and a large online audience had accumulated the company had the ability to get the original providers to work with them at a very reasonable cost, because the company controlled access to the customers that the original providers wanted to reach. (The platform became a major marketing “channel.”) In many cases the platform owner reduced costs further by cutting out various middlemen. It encouraged authors to write digital texts for them or began making its own movies. In the case of Uber it has begun to experiment by offering self-driving cars.

Although we haven’t put much emphasis on it in this chapter in the last chapter we described how AI will increasingly dominate software automation in the near future. Today’s AI technologies depend on access to large databases because AI applications are trained via the databases. The companies we have discussed—companies that interact with customers via a platform—are perfectly placed to gather vast amounts of data about what customers want and like. We have already mentioned trivial data-mining applications like those used by Amazon to identify other books customers might like. The same companies that are transforming their respective industries are the very companies that are investing heavily in AI and will be among the first to introduce natural language, decision support, and intelligent robotic applications in the near future.

We expect that the trends that are now apparent will dominate the next decade or two.

In essence, if a company is to survive in the years ahead its managers will need to think very seriously about the company’s business model. There are many ways to approach discussions of an organization’s business model. I suggest that the place to begin is to think about what value you are providing to your customers, and then move on and think about exactly what a customer has to do to receive value from your organization. Think about it from the customer’s perspective: What does the customer have to do to get your product or service? Usually, a customer relies on several processes—in much the same way there are several options on well-designed websites. You might look to see what books are available. You might establish an account. You might order a book. You might decide you want to cancel a book, or return it once it’s arrived. Consider each customer process in turn. Then think of what kind of platform you could develop to interface with the customer. It’s easy to imagine a website or a TV screen as a platform, but increasingly platforms will be more physical. As cars become self-driving they will become offices and entertainment platforms for their riders. Airplanes are already platforms in this way, as are smart phones and ATMs. These various platforms will increasingly structure or constrain the kinds of business processes you can design. Your job will be to develop a business model that can deliver value to customers by means of the various processes customers will use to access your business.

This book was written to provide today’s business managers and process practitioners an overview of the concepts and best practices available to them.

Before considering the future in any more detail, however, it might be useful to consider just what the situation is today. Business process improvement has been a perennial concern of companies ever since the Industrial Revolution began in the late 18th century. Moreover, as global markets have grown and the introduction of new technologies has accelerated, change has become the dominant feature of modern business. Competition today is fierce, and will grow more fierce in the near future as today’s companies struggle to establish global companies that can compete everywhere in the world. Nonprofit organizations and government institutions face similar problems as they seek to scale up to deal with discontinuous technology changes and global complexities. Organizations that survive and prosper will be those that master the need for constant innovation and change. The question we need to consider here is how organizations can best structure themselves to change and survive.

At present no consistent pattern can be found. Some companies seem to emphasize hiring creative individuals and living with the chaos of constant, radical change. Other companies, like Toyota, emphasize a process-focused approach and develop very systematic approaches to change. As a broad generalization, organizations that depend on people and creativity, like movie production, are more adapted to informal methods, while organizations that have huge investments in machinery and relatively long production times tend to be more systematic.

Even within a given industry, however, the commitment to process work varies. More to the point there is no agreement on who is ultimately responsible for change and innovation within a modern organization. Some emphasize strategy and innovation and tend to think of business executives as the leaders in driving organizational transformation. There are certainly a number of process initiatives that are demanded and driven by CEOs or divisional managers. Others emphasize professional teams that report to executives. The teams can either consist of individuals who think of themselves as change managers, as business process professionals, as Lean or Six Sigma practitioners, or as business analysts. In some cases these individuals may be staff members who report directly to division or department heads and in other cases they may be groups in a group dedicated to supporting process change within an organization. Some organizations assign process change to IT and expect the CIO to manage process improvement. Most organizations today, however, embrace a mixed approach, with process change agents in staff positions, in Lean Six Sigma teams, and in IT groups. Indeed, surveys suggest that one of the biggest problems facing process change people within organizations is the confusion among competing approaches and the difficulty they face obtaining senior management support for a single approach to a specific problem. Any vendor who has tried to sell process improvement consulting to business organizations knows the difficulty of identifying who is responsible for process work within any given organization. In a recent presentation to analysts IBM process marketing executives said that any major sale they wanted to make typically depended on obtaining the agreement of the COO, the head of a line of business, and the CIO—and that can be hard to do.

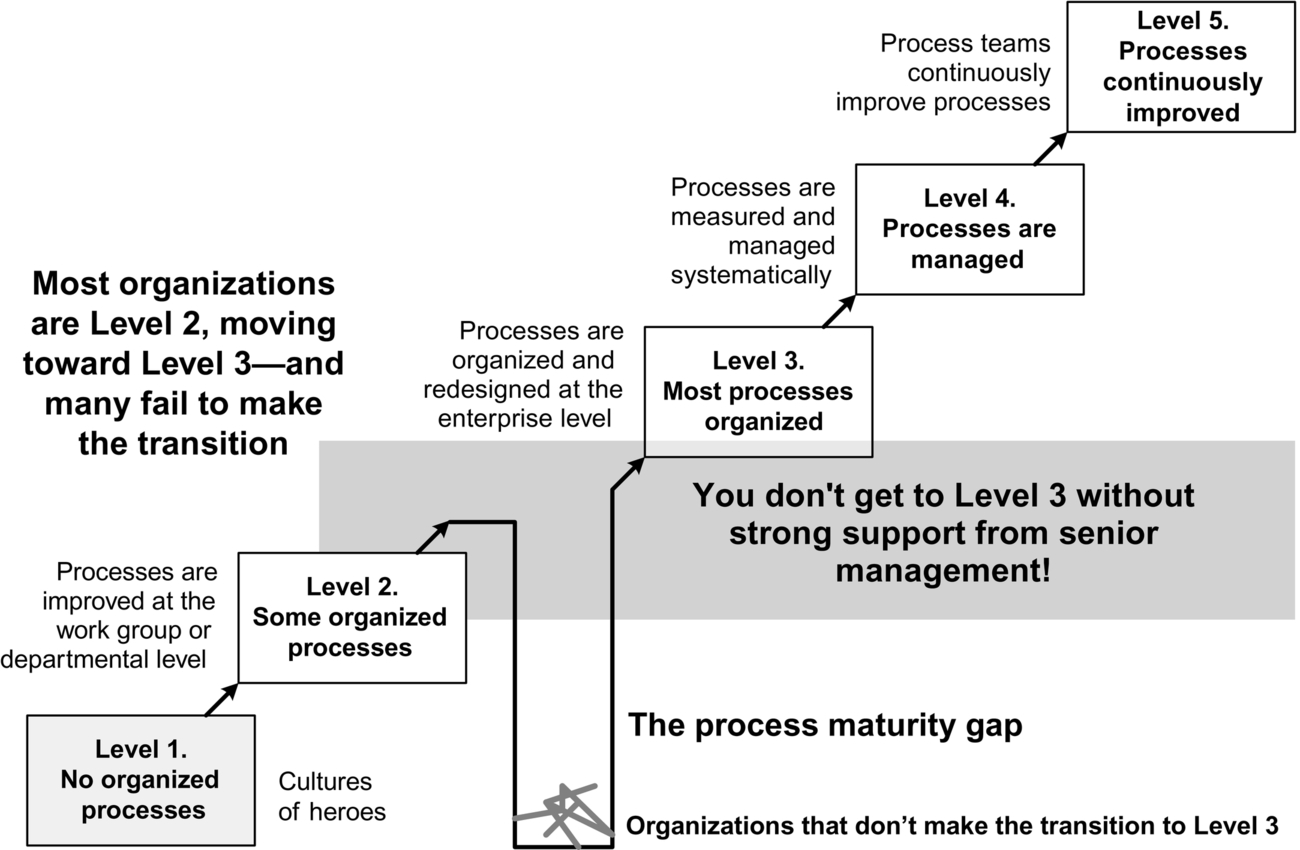

It would be nice to think that in the near future a process profession would emerge. There are business process management (BPM) programs in many universities and they will presumably graduate individuals who have a strong commitment to the process perspective, and to helping organizations become more systematic in improving their processes. Indeed, we are confident that will happen. The question, however, is whether it will be enough. We have often spoken of the Capability Maturity Model (CMM), which suggests that organizations must go through a series of steps as they become better able to utilize process concepts and practices. In the course of our consulting we have visited organizations all over the world that are at CMM Level 2. They have process teams—be they Lean, Six Sigma, BPM, or IT teams—and they are working at improving the business processes of their organizations. In many cases they have already completed impressive process improvement projects and seem certain to do more impressive work in the near future. We often leave such an organization thinking that it will soon be a Level 3 organization, then proceed to Level 4, and so forth. Frequently, having visited such an organization we return in a few years, fully expecting to see how they have progressed. Instead, we find different people working on different process problems, and the organization is still essentially at Level 2. In essence, the older group either never got up enough momentum to become a Level 3 organization, or worse they tried and failed. Figure 18.1 shows a CMM stairstep diagram with a gap where organizations that try for Level 3 and fail end up.

In our experience the key to crossing the chasm that lies between Level 2 and Level 3 on the CMM is sustained senior management support. A good process team can work hard at Level 2 and turn in impressive results. Their work can convince lots of other middle managers to give the process approach a chance. But, ultimately, a shift to enterprise-wide process modeling and systematic process measurement depends on senior executives. They have to provide the budget and the backing to assure that the organization as a whole gives the process perspective a real chance. Some executives get excited about what process can do and give it their backing. One thinks of Jack Welch at General Electric or of Fujio Cho at Toyota, both of whom worked hard to commit their organizations to a process focus. Other executives simply don’t get the process perspective and prefer to try and manage their organizations by relying on financial statements or by constantly rearranging the organization chart.

Most business schools that offer MBAs don’t put much emphasis on processes. If anything they do the opposite, teaching silo thinking by offering completely independent courses in Marketing, Manufacturing, and Finance. In most cases an MBA picks a specialty and then goes on to work for 20 years as a finance or a marketing manager before being given a shot at a senior executive position, when he or she is suddenly expected to think holistically about the organization.

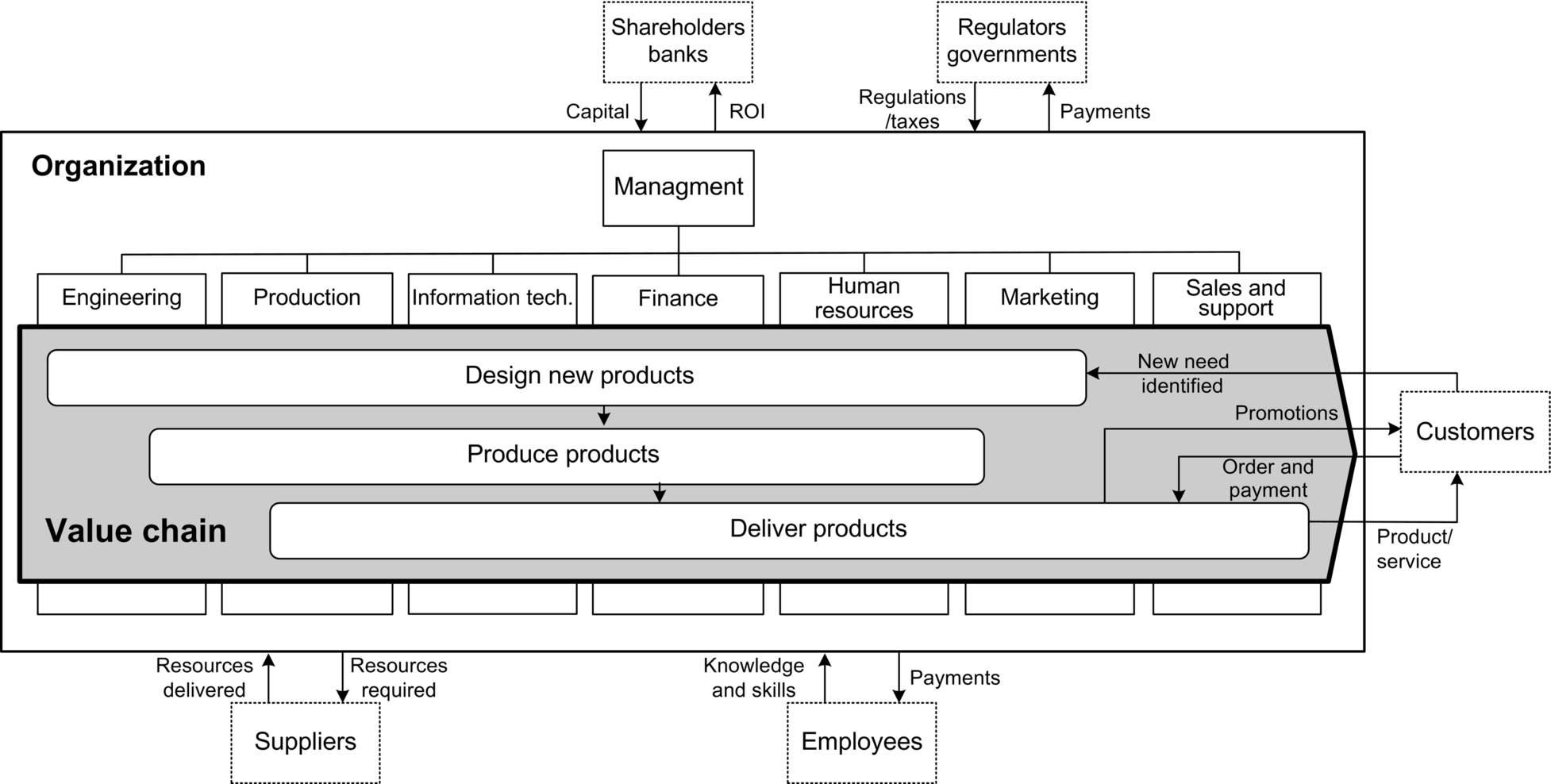

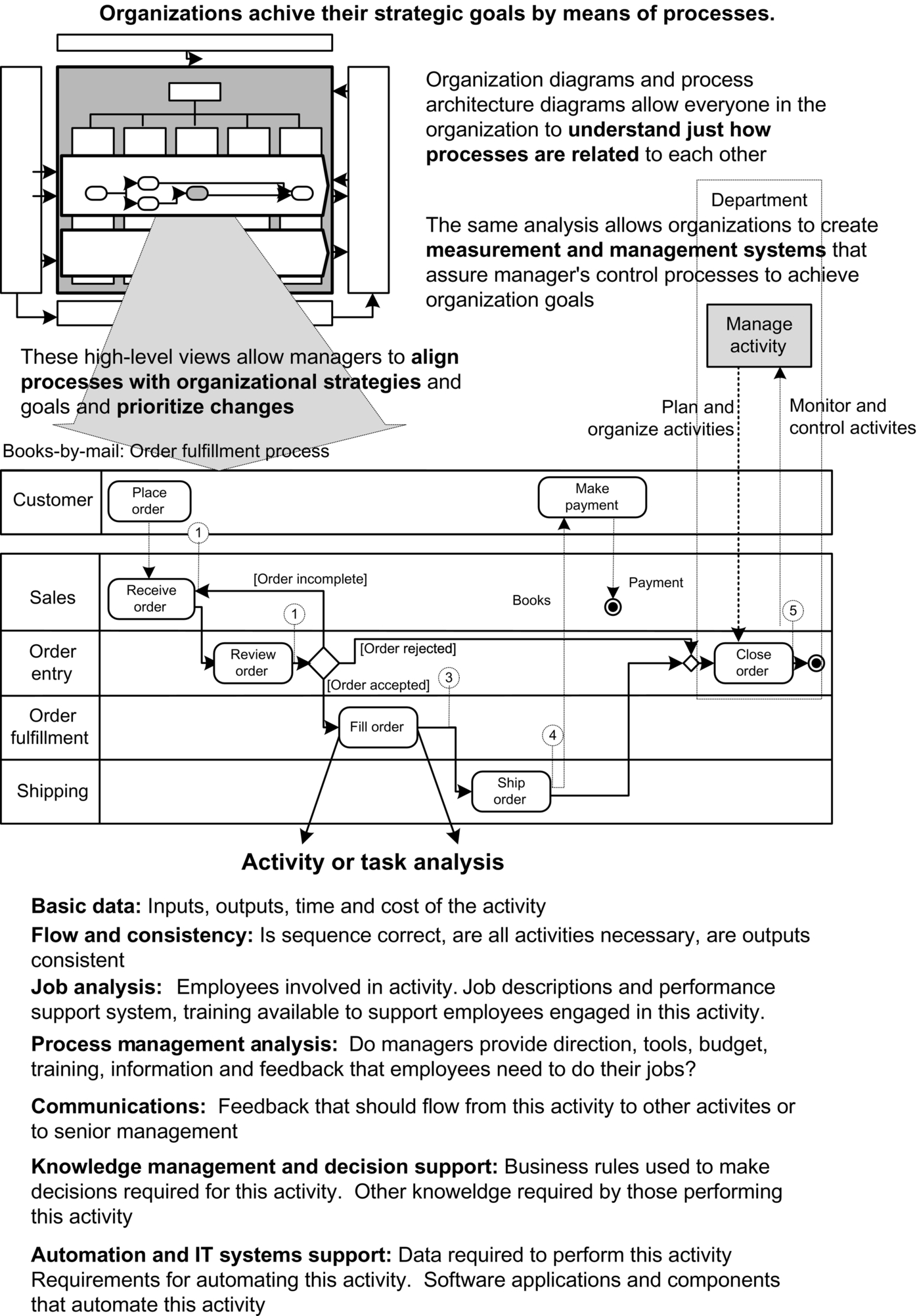

Those of us who believe in the value of the business process perspective face a twofold challenge. First, of course, we need to educate people in the concepts and practices of process improvement. If we don’t have people who can consistently improve an organization’s business processes, then we have no claim to anyone’s attention. Beyond that, however, we have to work to sell senior executives on the value of the process perspective. We need to convince executives that they will understand their organizations better and make better decisions if they conceptualize their organizations with process concepts. Figure 18.2 repeats a diagram that we used earlier to illustrate how a process perspective ties everything together.

Figure 18.2 shows the stakeholders (shareholders and customers), the departmental structure, and how all the departmental activities are tied together in cross-departmental processes that ultimately deliver value to customers and other stakeholders. In a more detailed version it would provide a diagram that one can use to track down the source of problems. If enough senior executives begin to think in terms of a process perspective an organization can begin to think about how it can change the way it works.

This book has ranged over a variety of topics, and considered issues that include both enterprise design and process improvement. Complete books have been written on several of the topics we treat in a single chapter. We have provided references to books and websites in the Notes and References that were placed at the end of each chapter to help interested readers pursue various topics in more detail. Our goal here was not to make readers into masters of tactical details, but to give them the basics they need to think strategically about how they should approach business process change in their organizations. We have posted a vocabulary of the terms used in this book on our associated website: http://www.bptrends.com. Each month we publish articles, book reviews, and reports on that website. All the material we have published over the course of the last decade is available at the website, so that visitors can search and find material that extends across all the various ideas covered in this book. The website is freely available and we urge readers to visit to extend and update the material presented in this book.

Finally, we want to end by briefly reiterating the major themes we have emphasized in this book.

First, there is the idea that organizations are systems. Things are related in complex ways, and we only understand organizations when we understand them as wholes. We believe that every manager should be able to draw an organization diagram of his or her organization at the drop of a hat. That would demonstrate at least high-level acquaintance with how various functions relate to each other and to suppliers and customers.

Second, we believe that the best way to understand how things get done and how any specific activity is related to others is to think in terms of processes. Process diagrams provide a good basis for demonstrating that one understands how things flow through an organization, from supplies and new technologies to products and services that are delivered to customers. In an ideal world we’d like every manager to be able to access a process model of the process he or she is managing by going to the company’s business process website. We believe that a basic acquaintance with process-diagramming techniques is just as important for today’s manager as familiarity with spreadsheets and organization charts.

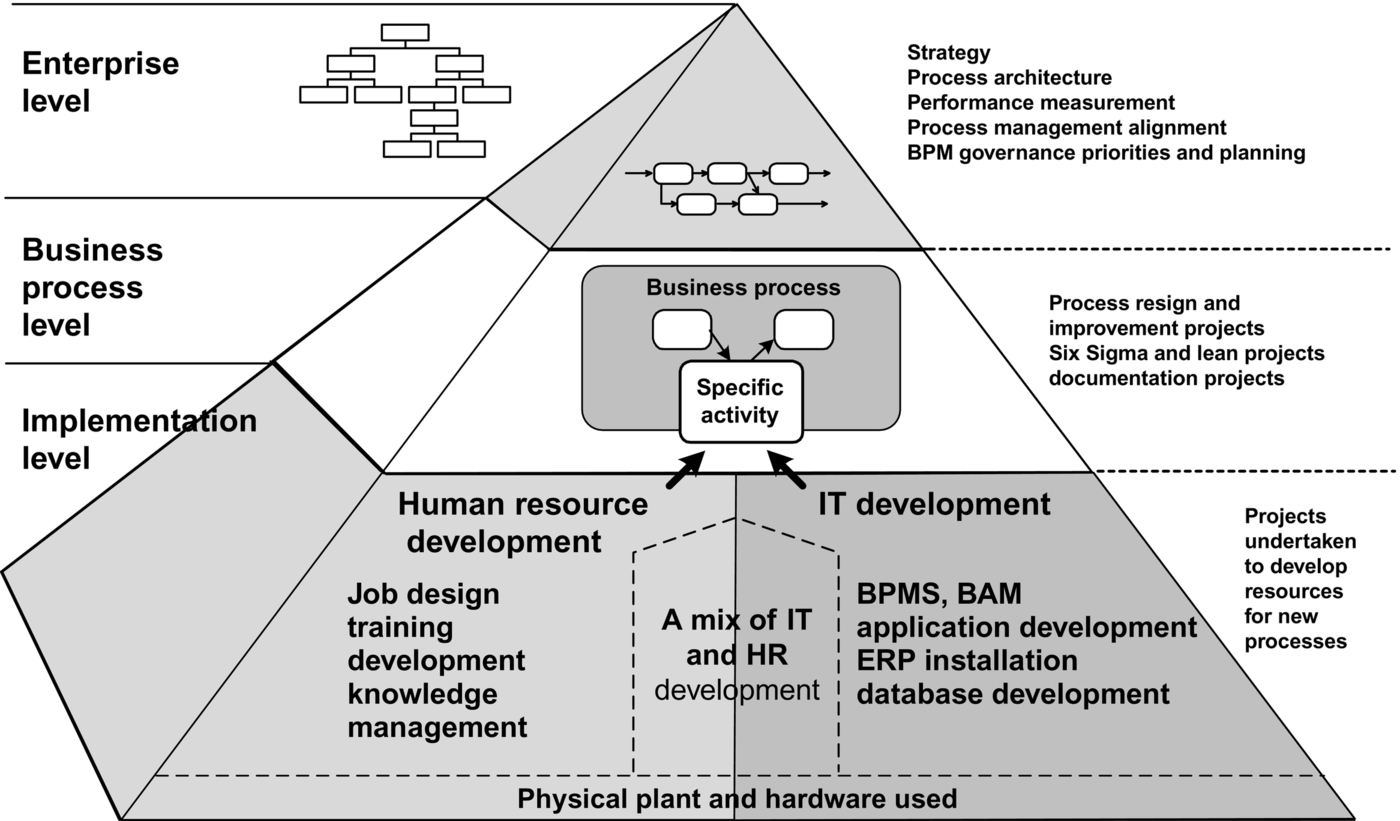

In the 1990s it was sufficient to understand processes. Today leading companies are moving beyond specific processes and trying to integrate all a company’s process data into enterprise tools that make it possible for senior managers to monitor and control the organization’s processes. Today this is being facilitated by business process modeling tools and repositories, and by exciting new approaches like business process frameworks. By the beginning of the next decade leading companies will be using business process management software (BPMS) applications to manage large-scale business processes on a day-by-day basis. At the same time companies are focusing on realigning their key performance indicators on processes and establishing a process management system. Thus a manager today not only needs to understand specific processes, but he or she needs to understand how all the processes in the company combine into a business process architecture. Figure 18.3 reproduces BPTrends’ process pyramid and highlights some of the different types of concerns and alignments that today’s manager should understand.

At the same time managers need to understand how the different processes are aligned to strategy and value chains and to a variety of enterprise resources. Figure 18.4 shows how processes can be key to understanding and organizing what is done in a company. A business process architecture provides everyone with an overview of how all the activities in the organization relate to one another and contribute to satisfying customers. A well-understood process shows how each activity relates to every other and where departments must interface for the process to be effective and efficient.

The same process diagram provides the basis for defining measures and aligning those measures with organization strategies and goals, departmental goals, and process and activity measures. This in turn defines the responsibilities of individual managers and supervisors. Each manager should know exactly what processes or activities he or she must plan and organize and just which measures to check to monitor and control the assigned processes and activities.

Drilling down in the diagram we see that well-defined activities provide the framework on which a whole variety of organizational efforts can be hung. Each activity should generate data on inputs and outputs, on time and cost. Activities are the basis for cost-based accounting systems. They are also key to analyzing jobs and developing job descriptions and training programs.

Activities also provide a framework for organizing knowledge management efforts, feedback systems, and decision support systems. And they also form the basic unit for database systems and for defining requirements if the activity is to be automated.

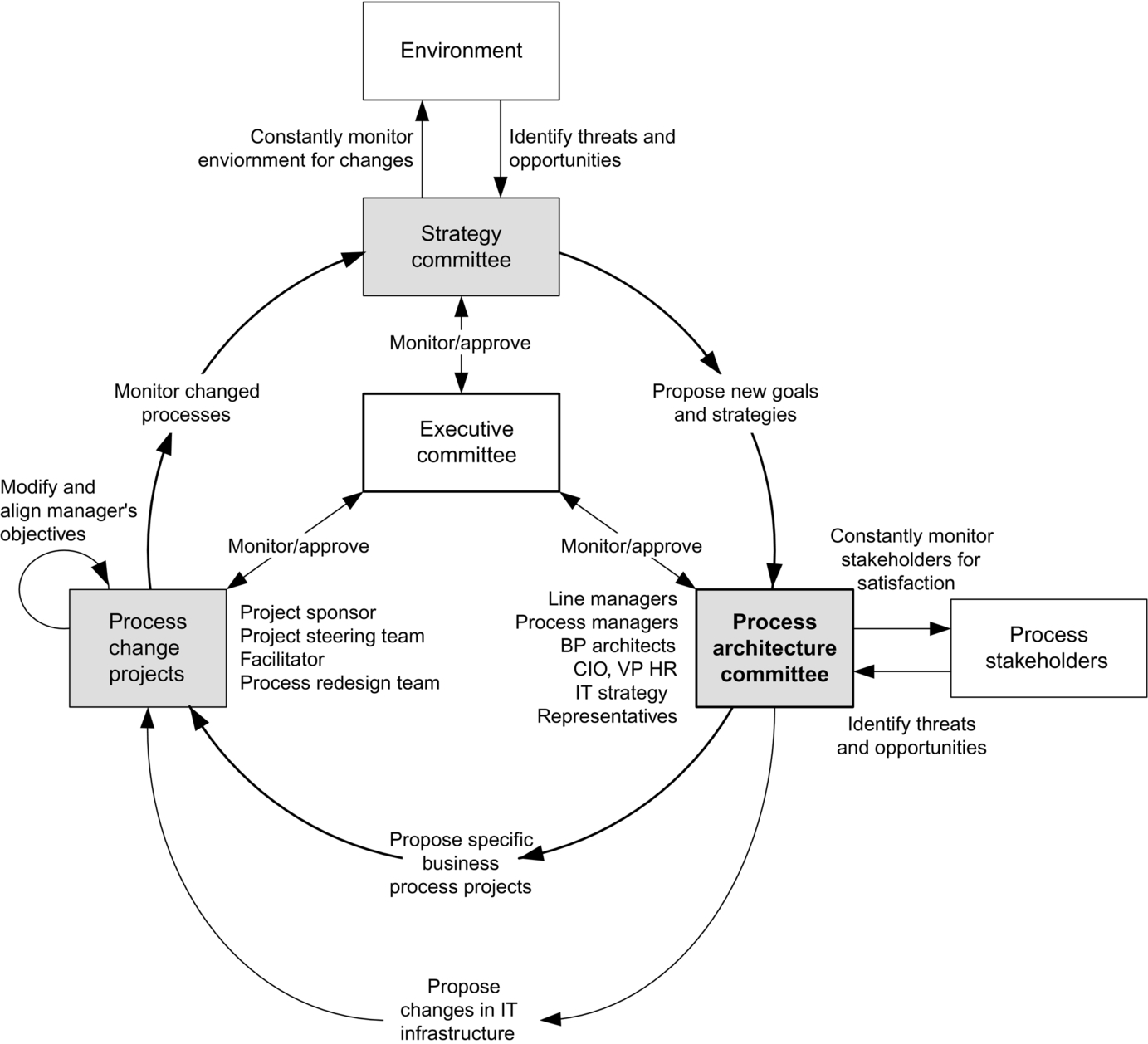

As enterprises become more mature in their understanding and use of processes they learn to constantly adjust their processes and to align the activities within a process in response to changes in their external environment. Each strategy change results in process changes. It also results in changes in the management and measurement systems and in all the other support systems that are tied to the processes and activities. Thus the process architecture becomes the heart of enterprise alignment and organizational adaptation.

We are constantly asked how to get started. You start from wherever you are. You need a major management commitment to do enterprise-level process work. If your management isn’t ready to make such a commitment you will need to work on local processes and build up some credibility while looking for a sponsor in your senior management group. The Software Engineering Institute’s maturity model provides a pretty good overview of how most companies evolve (see Figure I.5). Companies begin at Level 1 without processes. They move to Level 2 as they develop some processes—usually within departments or divisions. They move to Level 3 when they start to work on organizing all their processes together into an architecture. They move to Level 4 when they develop the process measurement and management systems necessary to truly control their processes. Increasingly, this will be the point at which leading companies will seek to install BPMS applications. Installing them if your organization is at a lower level is probably a waste of time. Finally, companies move to Level 5 and use Six Sigma or something very similar to constantly optimize their processes.

Moving up the CMM scale requires a major commitment on the part of an organization’s executives. It isn’t something that can be spearheaded by a departmental manager or a business process committee. It requires the active support of the CEO and the entire executive committee. Moreover, it isn’t something that can be done in a single push or in the course of a quarter or even a year. BPM and improvement must become part of an organization’s culture. Process improvement must become something that every manager spends time on each day. It must become one of the keys to understanding how the entire organization functions.

If business process improvement is to be ingrained in the organization, then improvement itself must become a systematic process. Every organization needs a BPM group to support senior management just as they need a finance committee to be available to provide financial information. The process architecture committee should be constantly working to align and realign corporate processes to corporate strategies and goals. As goals and strategies shift, process changes must be reprioritized and new process redesign or improvement projects must be undertaken. Just as senior executives receive daily or weekly reports on financial results they should also receive daily or weekly reports on how the various processes are achieving their assigned measures and what efforts are being undertaken to improve processes that fail to meet their goals. This kind of reporting assumes a matrix management structure, where there are managers with specific responsibilities for seeing the processes perform as wholes.

At the same time most organizations benefit from a Six Sigma program that makes all employees aware of the need for constant process improvement. A well-organized and integrated Six Sigma program is a major step toward creating a process-centric culture.

At the tactical level, process redesign and improvement have changed and will change more in the near future. In the early 1990s, when most managers first learned about process redesign, the organization and improvement of processes were regarded as tasks that should be handled by business managers. In effect, a redesign team determined what needed to be done. They only called the IT organization in when they decided they needed to automate some specific activities.

Today the use of IT and automation has progressed well beyond that early view of business process redesign. Increasingly, companies and information systems are so integrated that every process redesign is also a systems redesign. Today every IT organization is heavily involved in business process redesign. The Internet, email, and the Web have made it possible for IT organizations to achieve things today that they could only dream of in the early 1990s. Information systems are making it possible to integrate suppliers and partners—and in many cases, customers—in networks that are all made possible by software systems. AI will soon extend this and generate intelligent assistants of all kinds to assist human workers.

More important than technologies, however, is IT’s new commitment to working with business managers to improve processes. In essence, the business process is becoming the new basis for communication. IT will increasingly focus on offering solutions that improve specific processes, while keeping in mind how specific processes relate to other processes. As BPMS techniques evolve, we will see IT architects and business managers working to automate major business processes as BPMS applications that will facilitate rapid change and provide real-time monitoring capabilities for senior executives. The successful development of large-scale BPMS applications will bring IT and business managers together as never before.

To commit to managing an organization in a process-oriented manner requires that you commit to an ongoing process of change and realignment, and increasingly to BPM systems. The world keeps changing, and organizations must learn to keep changing as well. We have pictured this commitment as a cycle that never ends and is embedded within the core of the organization. We term it the enterprise alignment cycle (see Figure 18.5).

A process organization constantly monitors its external environment for changes. Changes can be initiated by competitors, by changes in customer taste, or by new technologies that allow the organization to create new products. When relevant changes occur the organization begins a process that results in new business processes with new characteristics, and new management systems that use new measures to assure that the new business processes deliver the required outputs. Organizations can only respond in this manner if all the managers in the organization understand processes. We hope this book will have done a bit to make the reader just such a manager.