Hour 11. Using Images in Your Website

What You’ll Learn in This Hour:

![]() How to place an image on a web page

How to place an image on a web page

![]() How to describe images with text

How to describe images with text

![]() How to specify image height and width

How to specify image height and width

![]() How to align images

How to align images

![]() How to use background images

How to use background images

![]() How to use imagemaps

How to use imagemaps

In the previous hour, you learned some of the basics for creating suitable images for your website; in this hour, you learn how to use these files in your website using HTML and CSS. Beyond just the basics of using the HTML <img/> tag to include images for display in a web browser, you’ll learn how to provide descriptions of these images (and why). You’ll also learn about image placement, including how to use images as backgrounds for different elements. Finally, you’ll learn how to use imagemaps, which allow you to use a single image as a link to multiple locations.

Placing Images on a Web Page

To get started with image placement on your website, first move the image file into the same folder as the HTML file or into a directory named images—often used for easy organization.

In this first example, let’s assume you have placed an image called myimage.gif in the same directory as the HTML file you want to use to display it. To display it, insert the following HTML tag at the point in the text where you want the image to appear, using the name of your image file instead of myimage.gif:

<img src="myimage.gif" alt="My Image" />

If your image file were in the images directory below the document root, you would use the following code, which you can see now contains the full path to myimage.gif in the images directory:

<img src="/images/myimage.gif" alt="My Image" />

Both the src and the alt attributes of the <img /> tag are required for valid HTML web pages. The src attribute identifies the image file, and the alt attribute enables you to specify descriptive text about the image. The alt attribute is intended to serve as an alternative to the image if a user is unable to view the image either because it is unavailable or because the user is using a text-only browser or screen reader. You’ll read more on the alt attribute later, in the section “Describing Images with Text.”

Note

It doesn’t matter to the web server, web browser, or end user just where you put your images, as long as you know where they are and you use the correct paths in your HTML code.

Personally, I prefer to put all my images in a separate images directory, or in a subdirectory of a generic assets directory (such as assets/images) so that all my images or other assets, such as multimedia and JavaScript files, are neatly organized.

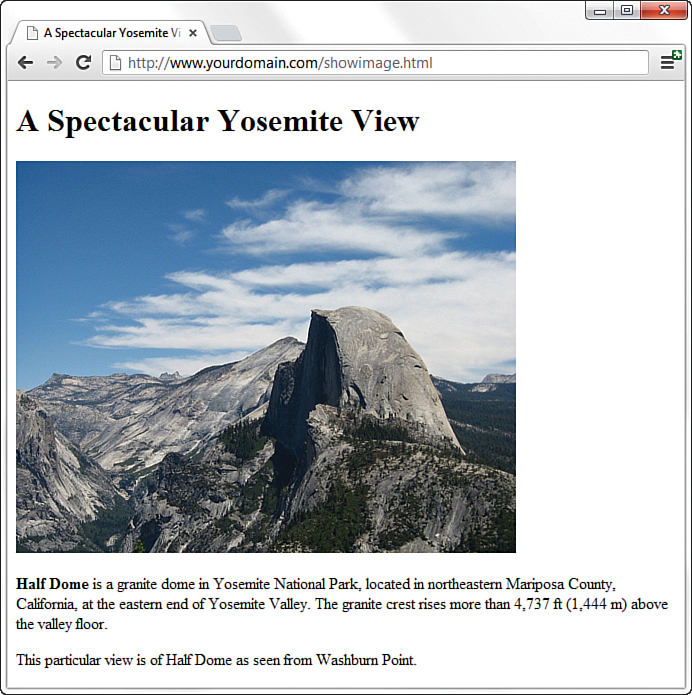

As an example of how to use the <img /> tag, Listing 11.1 inserts an image at the top of the page, before a paragraph of text. Whenever a web browser displays the HTML file in Listing 8.2, it automatically retrieves and displays the image file as shown in Figure 11.1.

Note

The <img /> tag is one of the HTML tags that also supports a title attribute; you can also use this attribute to describe an image, much like the alt attribute. However, the title attribute is problematic, in that it is displayed inconsistently across different user agents and thus cannot be relied upon. You might see the title attribute being used, and your HTML will be valid if you use it, but please do not use it in place of an alt attribute; doing so will limit your site’s usefulness on many types of devices.

FIGURE 11.1 When a web browser displays the HTML code shown in Listing 11.1, it renders the hd.jpg image.

LISTING 11.1 Using the <img /> Tag to Place Images on a Web Page

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>A Spectacular Yosemite View</title>

</head>

<body>

<section>

<header>

<h1>A Spectacular Yosemite View</h1>

</header>

<img src="hd.jpg" alt="Half Dome" />

<p><strong>Half Dome</strong> is a granite dome in Yosemite National

Park, located in northeastern Mariposa County, California, at the

eastern end of Yosemite Valley. The granite crest rises more than

4,737 ft (1,444 m) above the valley floor.</p>

<p>This particular view is of Half Dome as seen from Washburn

Point.</p>

</section>

</body>

</html>

Note

You can include an image from any website within your own pages. In those cases, the image is retrieved from the other page’s web server whenever your page is displayed. You could do this, but you shouldn’t! Not only is it bad manners (and probably a copyright violation) because you are using the other person’s bandwidth for your own personal gain, but it also can make your pages display more slowly. Additionally, you have no way of controlling when the image might be changed or deleted.

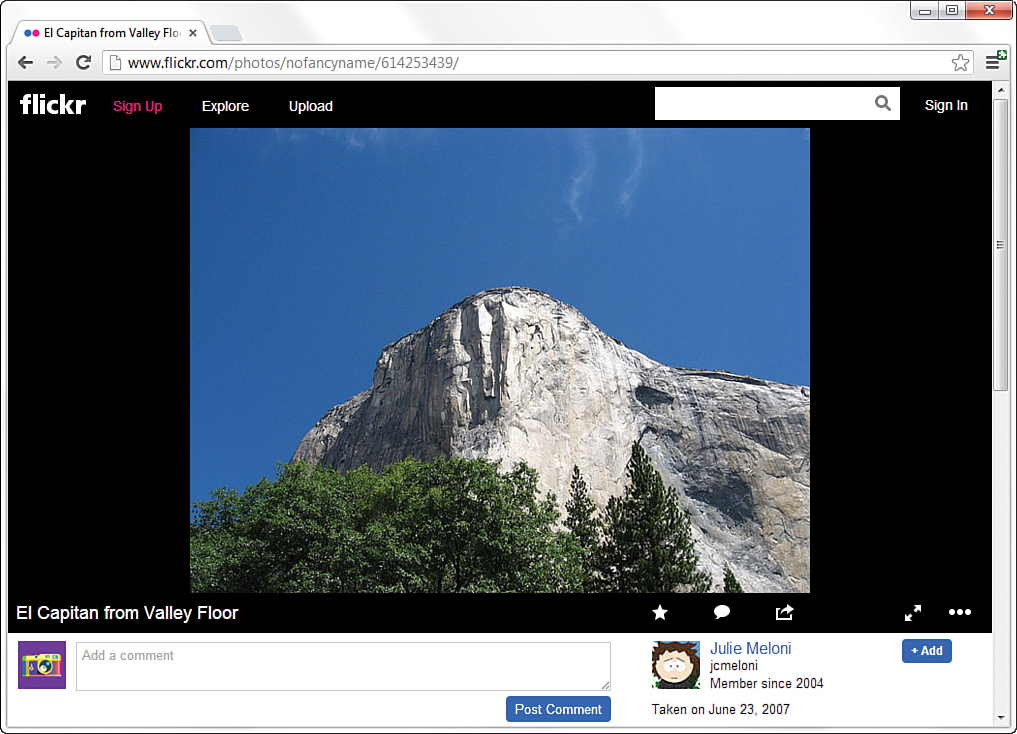

If you are granted permission to republish an image from another web page, always transfer a copy of that image to your computer and use a local file reference, such as <img src="myimage.jpg" /> instead of <img src="http://www.otherserver.com/theirimage.jpg" />. This advice is not applicable, however, when you host your images—such as photographs—at a service specifically meant as an image repository, such as Flickr (www.flickr.com). Services such as Flickr provide you with a URL for each image, and each URL includes Flickr’s domain in the address. The same is true if you want to link to images you have taken with mobile applications such as Instagram or Streamzoo (to name but a couple)—these services also provide you with a full URL to an image that you can then link to in your own website.

If you guessed that img refers to “image,” you’re right. Likewise, src refers to “source,” or a reference to the location of the image file. As discussed at the beginning of this book, an image is always stored in a file separate from the text of your web page (your HTML file), even though it appears to be part of the same page when viewed in a browser.

As with the <a> tag used for hyperlinks, you can specify any complete Internet address as the location of an image file in the src attribute of the <img /> tag. You can also use relative addresses, such as /images/birdy.jpg or ../smiley.gif.

Describing Images with Text

The <img /> tag in Listing 11.1 includes a short text message—in this case, alt="Half Dome". The alt stands for alternate text, which is the message that appears in place of the image itself if it does not load. An image might not load if its address is incorrect, if the Internet connection is very slow and the data has not yet transferred, or if the user is using a text-only browser or screen reader. Figure 11.2 shows one example of alt text used in place of an image. Each web browser renders alt text differently, but the information is still provided when it is part of your HTML document.

Even when graphics have fully loaded and are visible in the web browser, the alt message might appear in a little box (known as a ToolTip) whenever the mouse pointer passes over an image. The alt message also helps any user who is visually impaired (or is using a voice-based interface to read the web page).

You must include a suitable alt attribute in every <img /> tag on your web pages, keeping in mind the variety of situations in which people might see that message. A very brief description of the image is usually best, but web page authors sometimes put short advertising messages or subtle humor in their alt messages; too much humor and not enough information is frowned upon, because it is not all that useful. For small or unimportant images, it’s tempting to omit the alt message altogether, but the alt attribute is a required attribute of the <img /> tag. This doesn’t mean your page won’t display properly, but it does mean you’ll be in violation of HTML standards. I recommend assigning an empty text message to alt if you absolutely don’t need it (alt=""), which is sometimes the case with small or decorative images.

Specifying Image Height and Width

Because text moves over the Internet much faster than graphics, most web browsers end up displaying the text on a page before they display images. This gives users something to read while they’re waiting to see the pictures, which makes the whole page seem to load faster.

Tip

The height and width specified for an image don’t have to match the image’s actual height and width. A web browser tries to squish or stretch the image to display whatever size you specify. However, this is generally a bad idea because browsers aren’t particularly good at resizing images. If you know you want an image to display smaller, you’re definitely better off just resizing it in an image editor.

You can make sure that everything on your page appears as quickly as possible and in the right places by explicitly stating each image’s height and width. That way, a web browser can immediately and accurately make room for each image as it lays out the page and while it waits for the images to finish transferring.

For each image you want to include in your site, you can use your graphics program to determine its exact height and width in pixels. You might also be able to find these image properties by using system tools. For example, in Windows, you can see an image’s height and width by right-clicking the image, selecting Properties, and then selecting Details. When you know the height and width of an image, you can include its dimensions in the <img /> tag, like this:

<img src="myimage.gif" alt="Fancy Picture" width="200" height="100" />

Aligning Images

Just as you can align text on a page, you can align images on the page using special attributes. You can align images both horizontally and vertically with respect to text and other images that surround them.

Note

At the time of this writing, web developers and designers are discussing the creation and implementation of what are known as responsive images, or images that are displayed at different sizes and resolutions depending on the browser and media type. A new HTML5 element called <picture> has been introduced but is not yet part of the standard, nor is it implemented by many web browsers. If you plan to do any work with images on the web in the future, file away this information and check up on the status of this new element from time to time at http://picture.responsiveimages.org/.

Horizontal Image Alignment

As discussed in Hour 5, “Working with Text Blocks and Lists,” you can use the text-align CSS property to align content within an element as centered, aligned with the right margin, or aligned with the left margin. These style settings affect both text and images, and they can be used within any block element, such as <p>.

Like text, images are normally lined up with the left margin unless another alignment setting indicates that they should be centered or right-justified. In other words, left is the default value of the text-align CSS property.

You can also wrap text around images by using the float CSS property directly within the <img /> tag.

In Listing 11.2, <img style="float:left" /> aligns the first image to the left and wraps text around the right side of it, as you might expect. Similarly, <img style="float:right" /> aligns the second image to the right and wraps text around the left side of it. Figure 11.3 shows how these images align on a web page. There is no concept of floating an image to the center because there would be no way to determine how to wrap text on each side of it.

LISTING 11.2 Using float Style Properties to Align Images on a Web Page

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>More Spectacular Yosemite Views</title>

</head>

<body>

<section>

<header>

<h1>More Spectacular Yosemite Views</h1>

</header>

<p><img src="elcap_sm.jpg" alt="El Capitan" width="100"

height="75" style="float:left; padding: 12px;"/><strong>El

Capitan</strong> is a 3,000-foot (910 m) vertical rock formation

in Yosemite National Park, located on the north side of Yosemite

Valley, near its western end. The granite monolith is one of the

world's favorite challenges for rock climbers. The formation was

named "El Capitan" by the Mariposa Battalion when it explored the

valley in 1851.</p>

<p><img src="tunnelview_sm.jpg" alt="Tunnel View" width="100"

height="80" style="float:right; padding: 12px;"/><strong>Tunnel

View</strong> is a viewpoint on State Route 41 located directly east

of the Wawona Tunnel as one enters Yosemite Valley from the south.

The view looks east into Yosemite Valley including the southwest face

of El Capitan, Half Dome, and Bridalveil Falls. This is, to many, the

first views of the popular attractions in Yosemite.</p>

</section>

</body>

</html>

Note

Notice the addition of padding in the style attribute for both <img/> tags used in Listing 11.2. This padding provides some breathing room between the image and the text—12 pixels on all four sides of the image. You learn more about padding in Hour 13, “Working with Margins, Padding, Alignment, and Floating.”

Vertical Image Alignment

Sometimes you want to insert a small image in the middle of a line of text, or you want to put a single line of text next to an image as a caption. In either case, having some control over how the text and images line up vertically would be handy. Should the bottom of the image line up with the bottom of the letters, or should the text and images all be arranged so that their middles line up? You can choose between these and several other options:

![]() To line up the top of an image with the top of the tallest image or letter on the same line, use

To line up the top of an image with the top of the tallest image or letter on the same line, use <img style="vertical-align:text-top" />.

![]() To line up the bottom of an image with the bottom of the text, use

To line up the bottom of an image with the bottom of the text, use <img style="vertical-align:text-bottom" />.

![]() To line up the middle of an image with the overall vertical center of everything on the line, use

To line up the middle of an image with the overall vertical center of everything on the line, use <img style="vertical-align:middle" />.

![]() To line up the bottom of an image with the baseline of the text, use

To line up the bottom of an image with the baseline of the text, use <img style="vertical-align:baseline" />.

Note

The vertical-align CSS property also supports values of top and bottom, which can align images with the overall top or bottom of a line of elements, regardless of any text on the line.

All four of these options are used in Listing 11.3 and displayed in Figure 11.4. Four thumbnail images are now listed vertically down the page, along with descriptive text next to each image. Various settings for the vertical-align CSS property are used to align each image and its relevant text. This is certainly not the most beautiful page, but the various alignments should be clear to you.

LISTING 11.3 Using vertical-align Styles to Align Text with Images

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Small But Mighty Spectacular Yosemite Views</title>

</head>

<body>

<section>

<header>

<h1>Small But Mighty Yosemite Views</h1>

</header>

<p><img src="elcap_sm.jpg" alt="El Capitan" width="100"

height="75" style="vertical-align:text-top;"/><strong>El

Capitan</strong> is a 3,000-foot (910 m) vertical rock formation

in Yosemite National Park.</p>

<p><img src="tunnelview_sm.jpg" alt="Tunnel View" width="100"

height="80" style="vertical-align:text-bottom;"/><strong>Tunnel

View</strong> looks east into Yosemite Valley.</p>

<p><img src="upperyosefalls_sm.jpg" alt="Upper Yosemite Falls"

width="87" height="100" style="vertical-align:middle;"/><strong>Upper

Yosemite Falls</strong> are 1,430 ft and are among the twenty highest

waterfalls in the world. </p>

<p><img src="hangingrock_sm.jpg" alt="Hanging Rock" width="100"

height="75" style="vertical-align:baseline;"/><strong>Hanging

Rock</strong>, off Glacier Point, used to be a popular spot for people

to, well, hang from. Crazy people.</p>

</section>

</body>

</html>

Tip

If you don’t assign any vertical-align CSS property in an <img /> tag or class used with an <img /> tag, the bottom of the image will line up with the baseline of any text next to it. That means you never actually have to use vertical-align:baseline because it is assumed by default. However, if you specify a margin for an image and intend for the alignment to be a bit more exacting with the text, you might want to explicitly set the vertical-align attribute to text-bottom.

Turning Images into Links

You probably noticed in Figure 11.1 that the image on the page is quite large. This is fine in this particular example, but it isn’t ideal when you’re trying to present multiple images. It makes more sense to create smaller image thumbnails that link to larger versions of each image. Then you can arrange the thumbnails on the page so that visitors can easily see all the written content, even if they see only a smaller version of the actual (larger) image. Thumbnails are one of the many ways you can use image links to spice up your pages.

To turn any image into a clickable link to another page or image, you can use the <a> tag that you learned about in Hour 8, “Using External and Internal Links,” to make text links. Listing 11.4 contains the code to display thumbnails of images within text, with those thumbnails linking to larger versions of the images. To ensure that the user knows to click the thumbnails, the image and some helper text are enclosed in a <div>, as shown in Figure 11.5.

LISTING 11.4 Using Thumbnails for Effective Image Links

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>More Spectacular Yosemite Views</title>

<style type="text/css">

div.imageleft {

float:left;

clear: all;

text-align:center;

font-size:10px;

font-style:italic;

}

div.imageright {

float:right;

clear: all;

text-align:center;

font-size:10px;

font-style:italic;

}

img {

padding: 6px;

border: none;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<section>

<header>

<h1>More Spectacular Yosemite Views</h1>

</header>

<div class="imageleft">

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/nofancyname/614253439/"><img

src="elcap_sm.jpg" alt="El Capitan" width="100" height="75"/></a>

<br/>click image to enlarge</div>

<p><strong>El Capitan</strong> is a 3,000-foot (910 m) vertical rock

formation in Yosemite National Park, located on the north side of

Yosemite Valley, near its western end. The granite monolith is one

of the world's favorite challenges for rock climbers. The formation

was named "El Capitan" by the Mariposa Battalion when it explored

the valley in 1851.</p>

<div class="imageright">

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/nofancyname/614287355/"><img

src="tunnelview_sm.jpg" alt="Tunnel View" width="100" height="80"/></a>

<br/>click image to enlarge</div>

<p><strong>Tunnel View</strong> is a viewpoint on State Route 41

located directly east of the Wawona Tunnel as one enters Yosemite

Valley from the south. The view looks east into Yosemite Valley

including the southwest face of El Capitan, Half Dome, and

Bridalveil Falls. This is, to many, the first views of the

Popular attractions in Yosemite.</p>

</section>

</body>

</html>

The code in Listing 11.4 uses additional styles that are explained in more detail in later chapters, but you should be able to figure out the basics:

![]() The

The <a> tags link these particular images to larger versions, which, in this case, are stored on an external server (at Flickr).

![]() The

The <div> tags, and their styles, are used to align those sets of graphics and caption text (and also include some padding).

Unless instructed otherwise, web browsers display a colored rectangle around the edge of each image link. As with text links, the rectangle usually appears blue for links that haven’t been visited recently and purple for links that have been visited recently—unless you specify different-colored links in your stylesheet. Because you seldom, if ever, want this unsightly line around your linked images, you should usually include style="border:none" in any <img /> tag within a link. In this instance, the border:none style is made part of the stylesheet entry for the <img/> element because we use the same styles twice.

When you click one of the thumbnail images on the sample page shown, the link opens in the browser, as shown in Figure 11.6.

Using Background Images

As you learned in Hour 10, “Creating Images for Use on the Web,” you can use background images to act as a sort of wallpaper in a container element so that the text or other images appear on top of this underlying design.

The basic CSS properties that work together to create a background are as follows:

![]()

background-color: Specifies the background color of the element. Although it is not image related, it is part of the set of background-related properties. If an image is transparent or does not load, the user will see the background color instead.

![]()

background-image: Specifies the image to use as the background of the element using the following syntax: url('imagename.gif').

![]()

background-repeat: Specifies how the image should repeat, both horizontally and vertically. By default (without specifying anything), background images repeat both horizontally and vertically. Other options are repeat (same as default), repeat-x (horizontal), repeat-y (vertical), and no-repeat (only one appearance of the graphic).

![]()

background-position: Specifies where the image should be initially placed, relative to its container. Options include top-left, top-center, top-right, center-left, center-center, center-right, bottom-left, bottom-center, bottom-right, and specific pixel and percentage placements.

When specifying a background image, you can put all these specifications together into one property, like so:

body {

background: #ffffff url('imagename.gif') no-repeat top right;

}

In the previous stylesheet entry, the body element of the web page will be white and will include a graphic named imagename.gif at the top right. Another use for the background property is the creation of custom bullets for your unordered lists. To use images as bullets, first define the style for the <ul> tag, as follows:

ul {

list-style-type: none;

padding-left: 0;

margin-left: 0;

}

Next, change the declaration for the <li> tag to this:

li {

background: url(mybullet.gif) left center no-repeat

}

Make sure that mybullet.gif (or whatever you name your graphic) is on the web server and accessible; in this case, all unordered list items will show your custom image instead of the standard filled disc bullet.

We return to the specific use of background properties in Part III, “Advanced Web Page Design with CSS,” when using CSS for overall page layouts.

Using Imagemaps

Sometimes you want to use an image as navigation, but beyond the simple button-based or link-based navigation that you often see in websites. For example, perhaps you have a website with medical information, and you want to show an image of the human body that links to pages that provide information about various body parts. Or you have a website that provides a world map that users can click to access information about countries. You can divide an image into regions that link to different documents, depending on where users click within that image. This is called an imagemap, and any image can be made into an imagemap.

Why Imagemaps Aren’t Always Necessary

The first point to know about imagemaps is that you probably won’t need to use them except in very special cases. It’s almost always easier and more efficient to use several ordinary images that are placed directly next to one another and provide a separate link for each image.

For example, see Figure 11.7. This is a web page that shows 12 different corporate logos; this example is a common type of web page in the business world, in which you give a little free advertisement to your partners. You could present these logos as one large image and create an imagemap that provides links to each of the 12 companies. Users could click each logo in the image to visit each company’s site. But every time you wanted to add a new logo to the imagemap, you would have to modify the entire image and remap the hotspots—not a good use of anyone’s time. Instead, in this case when an imagemap is not warranted, you simply display the images on the page as in this example, by using 12 separate images (one for each company) and having each image include a link to that particular company.

FIGURE 11.7 Web page with 12 different logos; this could be presented as a single imagemap or divided into 12 separate pieces.

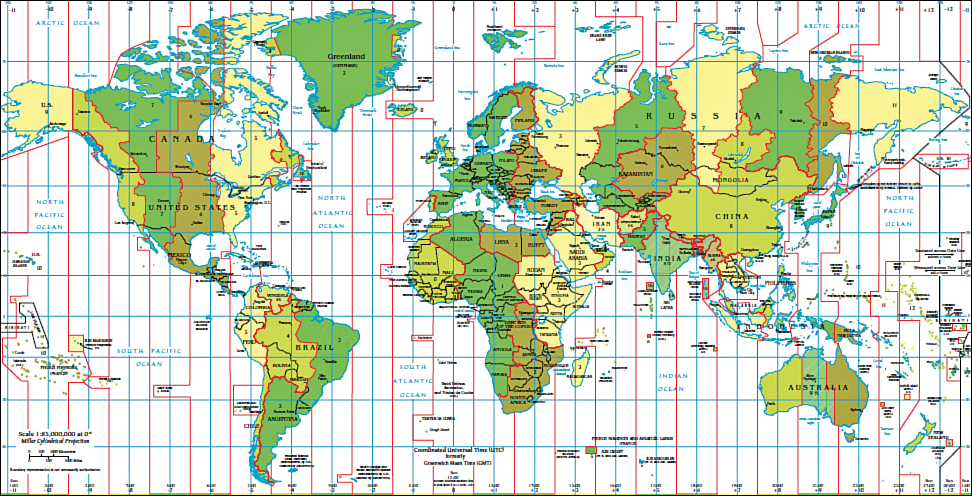

An imagemap is the best choice for an image that has numerous parts, is oddly arranged, or has a design that is itself too complicated to divide into separate images. Figure 11.8 shows an image that is best suited as an imagemap—a public domain image provided by the United States CIA of the standard time zones of the world.

FIGURE 11.8 This image wouldn’t respond well to being sliced up into perfectly equal parts—better make it an imagemap.

Mapping Regions Within an Image

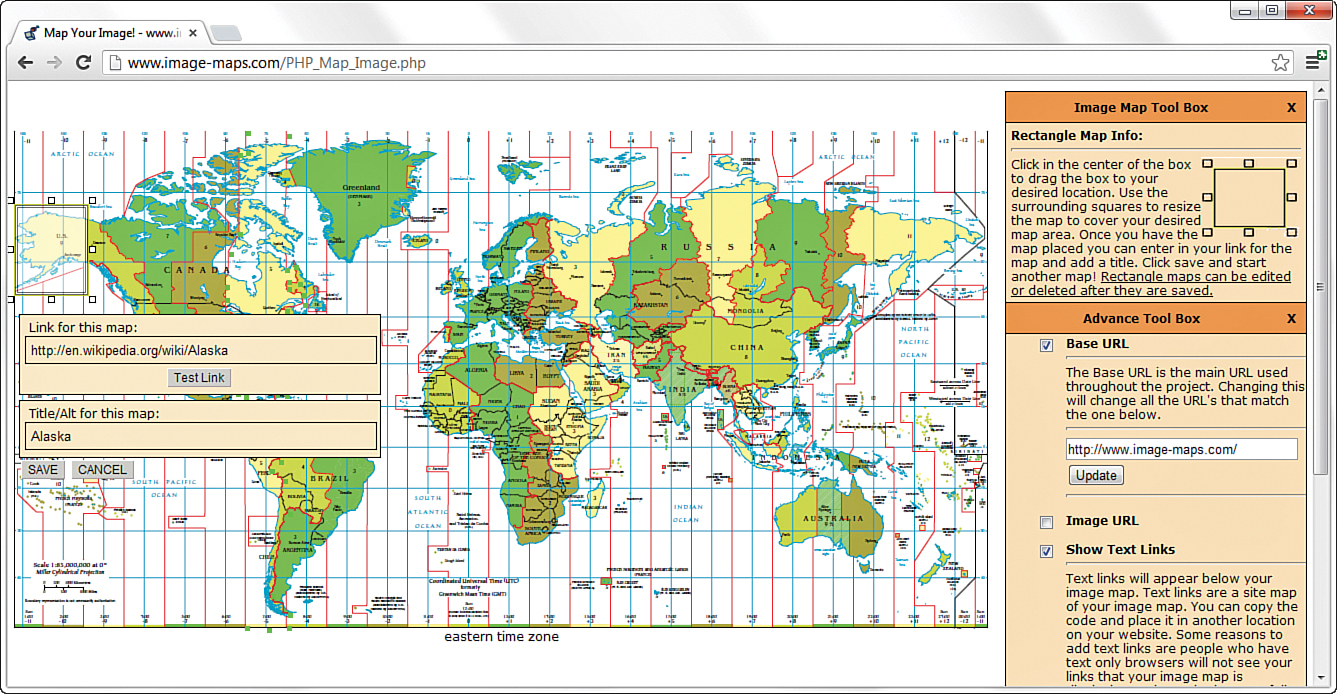

To create any type of imagemap, you need to figure out the numerical pixel coordinates of each region within the image that you want to turn into a clickable link. These clickable links are also known as areas. Your graphics program might provide you with an easy way to find these coordinates. Or you might want to use a standalone imagemapping tool such as Mapedit (http://www.boutell.com/mapedit/) or an online imagemap maker such as the one at http://www.image-maps.com/. In addition to helping you map the coordinates, these tools provide the HTML code necessary to make the maps work.

Using an imagemapping tool is often as simple as using your mouse to draw a rectangle (or a custom shape) around the area you want to be a link. Figure 11.9 shows the result of one of these rectangular selections, as well as the interface for adding the URL and the title or alternate text for this link. Several pieces of information are necessary to creating the HTML for your imagemap: coordinates, target URL, and alternate text for the link.

Creating the HTML for an Imagemap

If you use an imagemap generator, it will provide the necessary HTML for creating the imagemap. However, it is a good idea to understand the parts of the code so that you can check it for accuracy. The following HTML code is required to start any imagemap:

<map name="mapname">

Keep in mind that you can use whatever name you want for the name of the <map> tag, although it helps to make it as descriptive as possible. Next, you need an <area /> tag for each region of the image. Following is an example of a single <area /> tag that was produced by the actions shown in Figure 11.9:

<area shape="rect" coords="1,73,74,163"

href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaska"

alt="Alaska" title="Alaska" />

This <area /> tag has five attributes, which you use with every area you describe in an imagemap:

![]()

shape indicates whether the region is a rectangle (shape="rect"), a circle (shape="circle"), or an irregular polygon (shape="poly").

![]()

coords gives the exact pixel coordinates for the region. For rectangles, give the x,y coordinates of the upper-left corner followed by the x,y coordinates of the lower-right corner. For circles, give the x,y center point followed by the radius in pixels. For polygons, list the x,y coordinates of all the corners in a connect-the-dots order.

Here is an example of a mapped polygon—they can get a little crazy looking:

<area shape="poly"

coords="233,0,233,20,225,22,225,101,216,121,212,154,212,167,212,

181,222,195,220,209,226,214,226,234,232,252,224,253,223,261,231,

264,232,495,254,497,274,495,275,482,258,463,275,381,270,348,257,

338,266,329,272,313,271,301,258,292,264,284,262,262,272,263,272,

178,290,172,289,162,274,156,274,149,285,151,281,134,272,137,274,3"

href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Time_Zone"

alt="Eastern Time Zone" title="Eastern Time Zone"/>

![]()

href specifies the location to which the region links. You can use any address or filename that you would use in an ordinary <a> link tag.

![]()

alt enables you to provide a piece of text that is associated with the shape; as you learned previously, providing this text is important to users browsing with text-only browsers or screen readers. The use of title ensures that ToolTips containing the information are also visible when the user accesses the designated area.

Each distinct clickable region in an imagemap must be described as a single area, which means that a typical imagemap consists of a list of areas. After you’ve coded the <area /> tags, you are done defining the imagemap, so wrap things up with a closing </map> tag.

The last step in creating an imagemap is wiring it up to the actual map image. The map image is placed on the page using an ordinary <img /> tag. However, an extra usemap attribute is coded like this:

<img src="timezonemap.png" usemap="#timezonemap"

style="border:none; width:977px;height:498px"

alt="World Timezone Map" />

When specifying the value of the usemap attribute, use the name you put in the id of the <map> tag (and don’t forget the # symbol). Also include the style attribute to specify the height and width of the image and to turn off the border around the imagemap, which you might or might not elect to keep in imagemaps of your own.

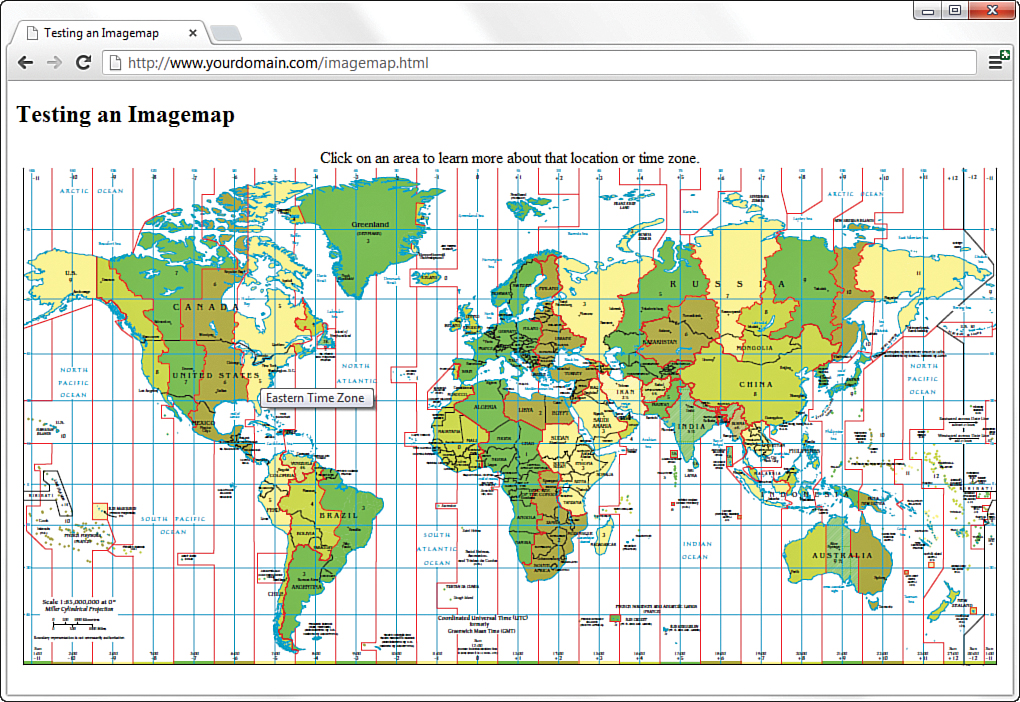

Listing 11.5 shows the complete code for a sample web page containing the map graphic, its imagemap, and a few mapped areas.

LISTING 11.5 Defining the Regions of an Imagemap with <map> and <area /> Tags

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Testing an Imagemap</title>

</head>

<body>

<section>

<header>

<h1>Testing an Imagemap</h1>

</header>

<div style="text-align:center"> Click on an area to learn more about

that location or time zone.<br/>

<img src="timezonemap.png" usemap="#timezonemap"

style="border:none; width:977px;height:498px "

alt="World Timezone Map" /></div>

<map name="timezonemap" id="timezonemap">

<area shape="poly" coords=" 233,0,233,20,225,22,225,101,216,121,212,

154,212,167,212,181,222,195,220,209,226,214,226,234,232,252,224,253,

223,261,231,264,232,495,254, 497,274,495,275,482,258,463,275,381,270,

348,257,338,266,329,272,313,271,301,258,292,264,284,262, 262,272,263,

272,178,290, 172,289,162,274,156,274,149,285,151,281,134,272,137,

274,3 "

href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/eastern_time_zone"

alt="Eastern Time Zone" title="Eastern Time Zone" />

<area shape="rect" coords="1,73,74,163 "

href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaska"

alt="Alaska" title="Alaska" />

</map>

</section>

</body>

</html>

Note

One method of producing mapped images relies solely on CSS, not the HTML <map> tag. You will learn more about this in Hour 16, “Using CSS to Do More with Lists.”

Figure 11.10 shows the imagemap in action. When you hover the mouse over an area, the alt or title text for that area—in this example, Eastern Time Zone—is displayed on the imagemap.

Summary

In this hour, you learned how to use images in your web pages. After creating, editing, or otherwise finding some images to use, you learned how to place them in your pages using the <img /> tag. You learned how to include a short text message that appears in place of the image as it loads and that also appears whenever users move the mouse pointer over the image. You also learned how to control the horizontal and vertical alignment of each image, and how to wrap text around the left or right of an image.

You learned how to use images as links—either by using the <a> tag around the images or by creating imagemaps. You also learned a little about how to use images in the background of container elements.

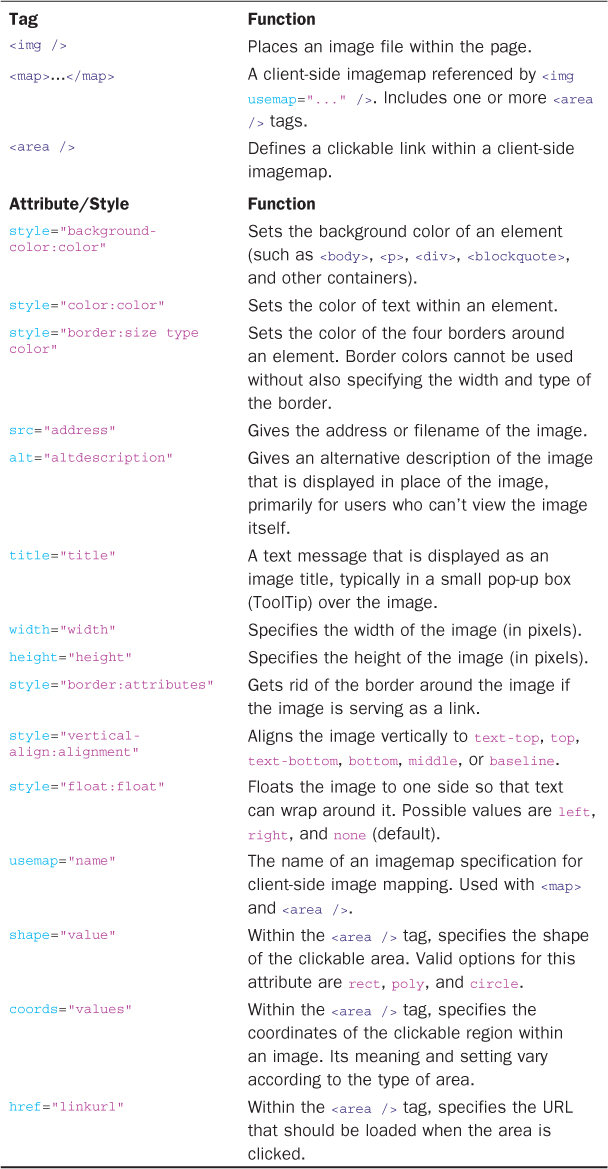

Table 11.1 summarizes the tags and attributes covered in this hour.

Q&A

Q. I used the <img /> tag just as you advised, but when I view the page, all I see is a little box with some shapes in it. What’s wrong?

A. The broken image icon you’re seeing can mean one of two things: Either the web browser couldn’t find the image file or the image isn’t saved in a format the browser recognizes. To solve these problems, first check to make sure that the image is where it is supposed to be. If it is, then open the image in your graphics editor and save it again as a GIF, JPG, or PNG.

Q. What happens if I overlap areas on an imagemap?

A. You are allowed to overlap areas on an imagemap. Just keep in mind that, when determining which link to follow, one area will has precedence over the other area. Precedence is assigned according to which areas are listed first in the imagemap. For example, the first area in the map has precedence over the second area, which means that a click in the overlapping portion of the areas will link to the first area. If you have an area within an imagemap that doesn’t link to anything (known as a dead area), you can use this overlap trick to deliberately prevent this area from linking to anything. To do this, just place the dead area before other areas so that the dead area overlaps them, and then set its href attribute to "".

Workshop

The Workshop contains quiz questions and exercises to help you solidify your understanding of the material covered. Try to answer all questions before looking at the “Answers” section that follows.

Quiz

1. How can you insert an elephant.jpg image file at the very top of a web page?

2. How would you make the word Elephant available to users when a web browser can’t display the actual elephant.jpg image or if a screen reader were in use?

3. If you had an image called myimage.png and you wanted to align it so that a line of text lined up at the middle of the image, what style property would you use?

Answers

1. Copy the image file into the same directory folder as the HTML text file. Immediately after the <body> tag in the HTML text file, type <p><img src="elephant.jpg" alt="" /></p>.

2. Use the following HTML:

<img src="elephant.jpg" alt="elephant" />

3. You would use vertical-align:middle to ensure that the text lined up at the middle of the image.

Exercises

![]() Practicing any of the image placement methods in this chapter will go a long way toward helping you determine the role that images can, and will, play in the websites you design. Using a few sample images, practice using the

Practicing any of the image placement methods in this chapter will go a long way toward helping you determine the role that images can, and will, play in the websites you design. Using a few sample images, practice using the float style to place images and text in relation to one another. Remember, the possible values for float are left, right, and none (default).

![]() Much like the previous exercise, use the various types of vertical alignment to lay out images and text on a web page of your choice.

Much like the previous exercise, use the various types of vertical alignment to lay out images and text on a web page of your choice.