Chapter 7. Sprite Behaviors

Great stories have great characters. And like books and movies, video games also need characters with interesting behaviors. For example, the protagonist in Braid—one of the most popular platform games of all time—can manipulate time. That ingenious behavior set the game apart from its contemporaries.

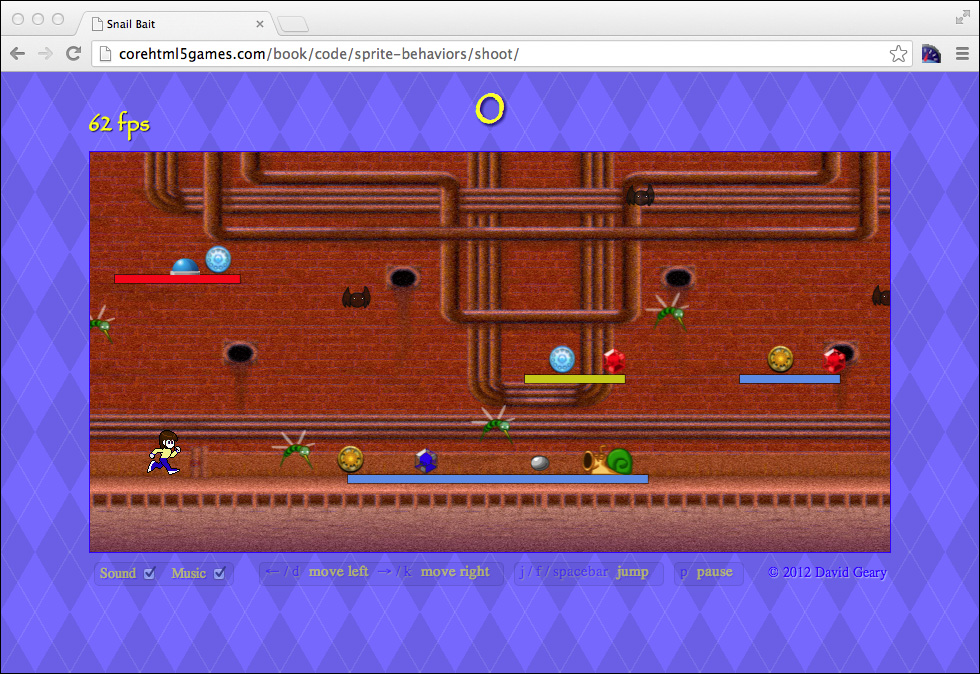

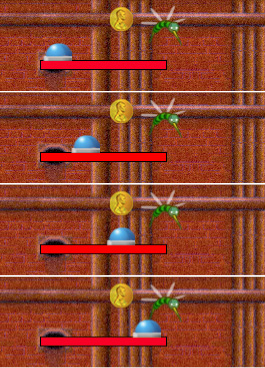

Behaviors are the soul of any video game, and adding behaviors to Snail Bait’s inert sprites immediately makes the game more interesting, as shown in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1. Sprites with behaviors

Recall that Snail Bait’s sprites do not implement their own activities such as running, jumping, or exploding. Instead, sprites rely on other objects, known as behaviors, to control how they act.

Figure 7.1 shows the snail shooting a snail bomb. Other behaviors that are not evident from the static image in Figure 7.1 are

• Bats and bees flapping their wings

• Buttons and the snail pacing back and forth on their platforms

• Coins throbbing

• Rubies and sapphires sparkling

• The runner running

• The snail bomb moving from right to left

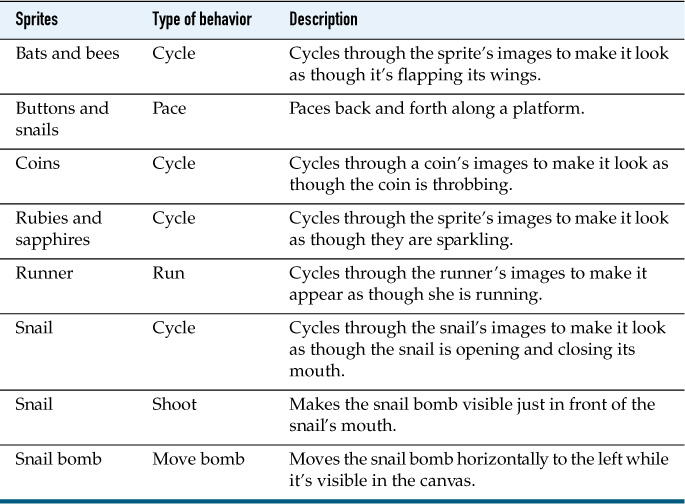

Table 7.1 summarizes the behaviors discussed in this chapter.

Table 7.1. Sprite behaviors discussed in this chapter

The behaviors listed in Table 7.1 represent less than half of Snail Bait’s behaviors. They are also the game’s most basic behaviors; jumping, for example, is considerably more complex, as discussed in forthcoming chapters. Nonetheless, there’s a lot to learn from the implementation of the simpler behaviors in this chapter, including how to do the following:

• Implement behaviors and assign them to sprites (Section 7.1 on p. 184)

• Cycle a sprite through a sequence of images (Section 7.3 on p. 189)

• Create flyweight behaviors to save on memory usage (Section 7.4 on p. 192)

• Implement behaviors that can be used in any game (Section 7.5 on p. 195)

• Combine behaviors to shoot projectiles (Section 7.6 on p. 202)

The online examples for this chapter are listed in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2. Sprite behavior examples online

![]() Note: Manipulating time

Note: Manipulating time

In Braid, the main character manipulates time, but every game developer is also a master at manipulating time. In this chapter, you will see the undercurrent of time flowing through behaviors; in the next two chapters, you’ll see how to bend time itself to implement nonlinear motion, which is the basis for realistic motion such as jumping and falling.

![]() Note: Types of behaviors

Note: Types of behaviors

In this chapter we discuss three types of behaviors:

• Sprite-specific

• Flyweights (stateless)

• Game-independent

Some behaviors, such as the runner’s run behavior, are sprite specific, meaning the behavior can be used only with a certain sprite.

Behaviors that do not maintain state are flyweights. Because they are stateless, a single flyweight behavior can be used with multiple sprites simultaneously. Flyweights can drastically reduce memory usage, especially for things like particle systems, which can consist of hundreds of sprites.

A third category of behaviors are game-independent behaviors, meaning general behaviors that work with any sprite. For example, in this chapter we discuss the implementation of a cycle behavior that cycles through a sprite’s images. You can use a cycle behavior with any sprite whose artist is a sprite sheet artist, regardless of the game in which the sprite resides. See Chapter 6 for more information about sprites and their artists.

7.1. Behavior Fundamentals

Any JavaScript object can be a behavior as long as it has an execute() method. Example 7.1 shows how to implement a behavior.

A behavior’s execute() method takes five arguments, in the following order:

• The sprite to which the behavior is attached (sprite)

• The current time (now)

Example 7.1. Implementing a behavior

var aBehavior = { // A JavaScript object with an execute() method

...

execute: function (sprite, now, context,

fps, lastAnimationFrameTime) {

// Manipulate the sprite depending on game condititions

}

};

• The game’s 2D graphics context (context)

• The game’s current frame rate (fps)

• The time of the last animation frame (lastAnimationFrameTime)

The preceding arguments determine how a behavior’s execute() method manipulates the sprite associated with the behavior for a given animation frame. For example, the behavior that moves the snail bomb from left to right calculates, from the bomb’s speed and the elapsed time since the last animation frame (now - lastAnimationFrameTime), how far to move the bomb for a given animation frame. See Example 7.17 to see the implementation of that behavior.

Behaviors are powerful for the following reasons:

• They enforce a separation of concerns between sprites and sprite behaviors, making both the code for sprites and the code for behaviors easier to read and maintain than if sprites directly implemented their behaviors.

• You can change a sprite’s behaviors at runtime.

• Stateless behaviors can be used as flyweights, meaning one behavior can be used with multiple sprites simultaneously, resulting in substantial reductions in memory usage.

• You can implement behaviors that work with any sprite and therefore can be used in multiple games.

• You can combine behaviors to create interesting personalities for your sprites.

Before we discuss the implementation details of the behaviors listed in Table 7.1, let’s have a high-level look at how to create behaviors and associate them with sprites. To that end, we’ll look at the runner’s collective behaviors.

![]() Note: Replica Island’s game components

Note: Replica Island’s game components

The idea for behaviors (originally called game components) comes from the popular open source Android game named Replica Island. See http://replicaisland.blogspot.com/2009/09/aggregate-objects-via-components.html for a blog post by Replica Island’s main developer about the benefits of game components (behaviors).

![]() Note: Use the graphics context with care

Note: Use the graphics context with care

Behaviors should not use the graphics context the game passes to their execute() method to draw, because drawing sprites is the responsibility of the sprite’s artist. Instead, behaviors should, as Snail Bait’s behaviors do, restrict their use of the graphics context to non-graphical functionality, such as determining whether a point lies within the current path. See Chapter 3 for more information on how behaviors use the graphics context.

7.2. Runner Behaviors

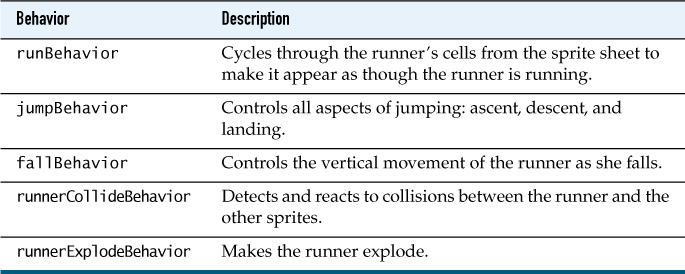

Snail Bait’s runner has five behaviors, listed in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3. The runner’s behaviors

Snail Bait ultimately instantiates the runner with an array of behaviors, as shown in Example 7.2.

The runner’s behaviors are shown in Example 7.3, with implementation details removed.

Example 7.2. Creating Snail Bait’s runner

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.runner = new Sprite(

'runner', // Type

new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet, // Artist

this.runnerCellsRight),

[ this.runBehavior, // Behaviors

this.jumpBehavior,

this.fallBehavior,

this.runnerCollideBehavior

this.runnerExplodeBehavior

]

);

...

};

Example 7.3. Runner behavior objects

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.runBehavior = {

execute: function(sprite, now, context, fps,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

...

}

};

this.jumpBehavior = {

execute: function(sprite, now, context, fps,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

...

}

};

this.fallBehavior = {

execute: function(sprite, now, context, fps,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

...

}

};

this.runnerExplodeBehavior = {

execute: function(sprite, now, context, fps,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

...

}

};

this.runnerCollideBehavior = {

execute: function(sprite, now, context, fps,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

...

}

};

...

};

Because the runner’s behaviors are associated only with the runner, the sprite that Sprite.update(), listed in Example 7.4, passes to each behavior is always the runner.

Sprite.prototype = {

update: function (now, fps, context, lastAnimationFrameTime) {

for (var i=0; i < this.behaviors.length; ++i) {

this.behaviors[i].execute(this, now, fps,

lastAnimationFrameTime);

}

}

...

};

Recall that Snail Bait continuously — once per animation frame — iterates over all visible sprites, invoking each sprite’s update() method. As you can see in Example 7.4, the Sprite.update() method iterates over a sprite’s behaviors, invoking each behavior’s execute() method.

A behavior’s execute() method, therefore, is not like the methods of ordinary JavaScript objects whose methods are invoked relatively infrequently; instead, each behavior’s execute() method is like a little motor that’s constantly running.

Now that you understand how sprites and behaviors fit together, let’s see how to implement behaviors.

![]() Note: Behaviors are implemented in Snail Bait’s constructor

Note: Behaviors are implemented in Snail Bait’s constructor

A behavior’s execute() methods are not methods of the SnailBait object, so they are not defined in Snail Bait’s prototype object. Instead, those execute() methods reside in behavior objects that the game defines in its constructor function, as you can see in Example 7.3.

![]() Note: The Strategy design pattern

Note: The Strategy design pattern

Behaviors are an example of the Strategy design pattern, which encapsulates algorithms into objects. At runtime, you can mix and match those algorithms. Behaviors give you more flexibility than would hard-coding their algorithms directly into individual sprites. You can read more about the Strategy design pattern at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategy_pattern.

![]() Note: Behaviors as machines

Note: Behaviors as machines

Behaviors are like little machines that are constantly running. As long as a behavior’s associated sprite is visible, Snail Bait invokes the behavior’s execute() method every animation frame. Some behaviors, such as the runner’s run behavior, are constantly doing something meaningful nearly every animation frame; other behaviors, however, such as the runner’s exploding behavior, are idle most of the time.

7.3. The Runner’s Run Behavior

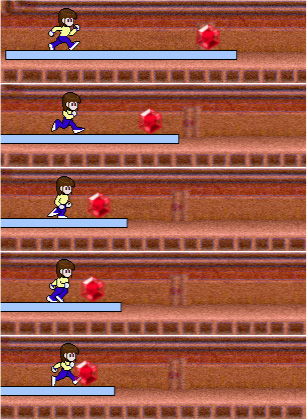

Snail Bait does two things that make it appear as though the runner is running. First, as you saw in Chapter 3, the game continuously scrolls the background, making it appear as though the runner is moving horizontally. Second, the runner’s run behavior cycles the runner through a sequence of images from the game’s sprite sheet, as shown in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2. The run behavior. Notice the different poses for the runner.

The code in Example 7.5 implements the run behavior.

The run behavior’s execute() method periodically advances the runner’s artist to the next image in the runner’s sequence from the game’s sprite sheet.

The rate at which the run behavior advances the runner’s image determines how quickly the runner runs. That rate is controlled with the runner’s runAnimationRate property.

The runner is not running when the game starts, so its runAnimationRate is initially zero. As you can see from Example 7.5, the run behavior does nothing when the runner’s runAnimationRate is zero.

Example 7.5. The runner’s run behavior

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.runBehavior = {

lastAdvanceTime: 0,

execute: function (sprite,

now,

fps,

context,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

if (sprite.runAnimationRate === 0) { // not running

return;

}

if (this.lastAdvanceTime === 0) { // skip first time

this.lastAdvanceTime = now;

}

else if (now - this.lastAdvanceTime >

1000 / sprite.runAnimationRate) { // time to advance

sprite.artist.advance();

this.lastAdvanceTime = now;

}

}

};

...

};

When the player turns left or right, Snail Bait sets the runAnimationRate to snailBait.RUN_ANIMATION_RATE (30 frames/second), the run behavior kicks in, and the runner starts to run. The turnLeft() and turnRight() methods are listed in Example 7.6.

Example 7.6. Turning starts the run animation

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.RUN_ANIMATION_RATE = 30; // frames per second

...

};

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

turnLeft: function () {

this.bgVelocity = -this.BACKGROUND_VELOCITY;

this.runner.runAnimationRate = this.RUN_ANIMATION_RATE;

this.runnerArtist.cells = this.runnerCellsLeft;

this.runner.direction = snailBait.LEFT;

},

turnRight: function () {

this.bgVelocity = this.BACKGROUND_VELOCITY;

this.runner.runAnimationRate = this.RUN_ANIMATION_RATE;

this.runnerArtist.cells = this.runnerCellsRight;

this.runner.direction = snailBait.RIGHT;

},

...

};

The game’s keyboard event handlers invoke the turnLeft() and turnRight() methods, to control the direction in which the runner appears to move. Those methods set Snail Bait’s bgVelocity property, which is the rate at which the background scrolls.

The turnLeft() and turnRight() methods also set the appropriate cells (either left poses or right) from the game’s sprite sheet for the runner’s artist.

![]() Note: The flow of time

Note: The flow of time

Like the runner’s run behavior, nearly all behaviors are predicated on time. And because a game’s animation is constantly in effect, many functions that modify a game’s behavior, such as turnLeft() and turnRight() in Example 7.6, do so by simply setting game properties. When the game draws the next animation frame, those properties influence the game’s behavior.

7.4. Flyweight Behaviors

The runner’s run behavior discussed in the preceding section maintains state, namely, the time at which the behavior last advanced the sprite’s image. That state tightly couples the runner to the run behavior. So, for instance, if you wanted to make another sprite run, you would need to have another run behavior.

Behaviors that do not maintain state are known as flyweights. They are more flexible because they can be used by many sprites simultaneously. Example 7.7 illustrates a stateless pace behavior that makes sprites pace back and forth on a platform. A single instance of that behavior is used for the game’s buttons and its snail, all of which pace back and forth on their platforms. Figure 7.3 shows a button pacing on a platform.

Example 7.7 shows Snail Bait’s createButtonSprites() method, which adds the lone pace behavior to each button.

Example 7.7. Creating pacing buttons

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

createButtonSprites: function () {

var button;

for (var i = 0; i < this.buttonData.length; ++i) {

if (i !== this.buttonData.length - 1) {

button = new Sprite('button',

new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.blueButtonCells),

[ this.paceBehavior, ... ]);

}

else {

button = new Sprite('button',

new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.goldButtonCells),

[ this.paceBehavior, ... ]);

}

button.width = this.BUTTON_CELLS_WIDTH;

button.height = this.BUTTON_CELLS_HEIGHT;

button.velocityX = this.BUTTON_PACE_VELOCITY;

this.buttons.push(button);

}

},

...

};

The createButtonSprites() method iterates over the metadata for the game’s buttons, creating a button for every metadata object. All the buttons are blue except for the last button, which is gold.

Example 7.8 shows the implementation of the paceBehavior object.

The pace behavior modifies a sprite’s horizontal position. The behavior implements time-based motion to calculate how many pixels to move the sprite for the current animation frame by multiplying the sprite’s velocity by the time it took to draw the last animation frame. See Chapter 3 for more information about time-based motion.

Example 7.8. The pace behavior

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.paceBehavior = {

execute: function (sprite, now, fps, context,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

this.setDirection(sprite);

this.setPosition(sprite, now, lastAnimationFrameTime);

}

setDirection: function (sprite) {

var sRight = sprite.left + sprite.width,

pRight = sprite.platform.left + sprite.platform.width;

if (sprite.direction === undefined) {

sprite.direction = snailBait.RIGHT;

}

if (sRight > pRight && sprite.direction === snailBait.RIGHT) {

sprite.direction = snailBait.LEFT;

}

else if (sprite.left < sprite.platform.left &&

sprite.direction === snailBait.LEFT) {

sprite.direction = snailBait.RIGHT;

}

},

setPosition: function (sprite, now, lastAnimationFrameTime) {

var pixelsToMove = sprite.velocityX *

(now - lastAnimationFrameTime) / 1000;

if (sprite.direction === snailBait.RIGHT) {

sprite.left += pixelsToMove;

}

else {

sprite.left -= pixelsToMove;

}

},

};

...

};

![]() Note: Flyweights and state

Note: Flyweights and state

The pace behavior can be used as a flyweight because it’s stateless. It’s stateless because it stores state—each sprite’s position and direction—in the sprites themselves.

7.5. Game-Independent Behaviors

In Section 7.3, “The Runner’s Run Behavior,” on p. 189 of this chapter, we discussed the runner’s run behavior, which is a stateful behavior that’s tightly coupled to a single sprite. The paceBehavior, which we discussed in Section 7.4, “Flyweight Behaviors,” on p. 192, is a stateless behavior, which decouples it from individual sprites so a single instance can be used by multiple sprites.

Behaviors can be generalized even further. You can decouple behaviors not only from individual sprites but also from the game itself. Snail Bait uses three behaviors that can be used in any game:

• bounceBehavior

• cycleBehavior

• pulseBehavior

The bounce behavior bounces a sprite up and down; the cycle behavior cycles a sprite through a set of images; and the pulse behavior manipulates a sprite’s opacity to make it appear as though the sprite is pulsating.

The bounce and pulse behaviors both involve nonlinear animation, which we discuss in Chapter 9. The cycle behavior cycles through a sprite’s images linearly, however, so we use the implementation of that behavior to illustrate implementing behaviors that can be used in any game.

7.5.1. The Cycle Behavior

The cycle behavior cycles through a sprite’s images, showing each image for a specific duration. Example 7.9 shows the implementation of the cycle behavior.

Example 7.9. The cycle behavior

CycleBehavior = function (duration, interval) {

this.duration = duration || 1000; // milliseconds

this.lastAdvance = 0;

this.interval = interval;

};

CycleBehavior.prototype = {

execute: function (sprite, now, fps, context,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

if (this.lastAdvance === 0) { // First time only

this.lastAdvance = now;

}

if (this.interval && // If there's an interval,

sprite.artist.cellIndex === 0) { // and the cycle is complete

// If interval is over

if (now - this.lastAdvance > this.interval) {

sprite.artist.advance(); // advance

this.lastAdvance = now;

}

}

else if (now - this.lastAdvance > this.duration) {

sprite.artist.advance();

this.lastAdvance = now;

}

}

};

The cycle behavior endlessly cycles through its associated sprite’s images from the game’s sprite sheet. The duration you pass to the CycleBehavior constructor represents the amount of time each image is visible, and it’s optional; if you don’t specify the duration, it defaults to one second.

The interval represents a time gap between cycles. The interval is also optional. In fact, Snail Bait’s only cycle behavior that has an interval is the one associated with the snail, which cycles through its images and then waits for 1.5 seconds before starting the cycle again. That 1.5 second interval throttles the rate at which the snail fires snail bombs; without it, the snail would continuously fire snail bombs when the snail is in view. See Section 7.6, “Combining Behaviors,” on p. 202 for more details.

The cycle behavior’s simple implementation belies its significance:

• The cycle behavior is neither sprite- nor game-specific.

• The cycle behavior is general enough that it can be used for many types of effects.

• You can easily modify the cycle behavior to be a flyweight.

The cycle behavior is not coupled to any sprite, so it can be reused in other games. In contrast, the sprite-specific run behavior in Example 7.5, even though it has a lot in common with the cycle behavior, takes into account the runner’s animation rate, which is specific to the runner and therefore the run behavior cannot be reused.

The general nature of the cycle behavior is the source of its reusability, and it’s also the reason that cycle behaviors can be used to implement different kinds of effects. Because it cycles through a sequence of images, a cycle behavior is similar to a flip book where you define what goes on each page. Snail Bait uses cycle behaviors for several effects, including

• Sparkling rubies and sapphires

• Bats and bees that flap their wings

• Throbbing coins

We discuss each of those effects in the following sections.

![]() Best Practice: Generalize behaviors

Best Practice: Generalize behaviors

It’s a good idea to look for opportunities to generalize behaviors so that they can be used in a wider range of circumstances.

![]() Note: Cycle behaviors as flyweights

Note: Cycle behaviors as flyweights

It’s only about 20 lines of code, but the cycle behavior is useful because it’s the source of many types of effects and can be used in multiple games. Cycle behaviors, however, maintain state, so they are coupled to a particular sprite. If cycle behaviors instead stored that state in sprites themselves, the behaviors would be stateless and you could use one cycle behavior for many sprites.

7.5.1.1. Sparkling Rubies and Sapphires

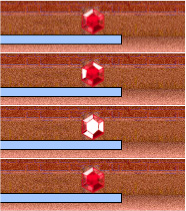

Snail Bait’s rubies and sapphires sparkle, as shown in Figure 7.4.

Snail Bait’s sprite sheet contains sequences of images for both rubies and sapphires. Cycling through those images creates the sparkling illusion.

Example 7.10 shows the Snail Bait method that creates rubies. A nearly identical method (not shown) creates sapphires. The createRubySprites() method also creates a cycle behavior that every 500 ms displays the next image from the ruby-sparkling sequence for a duration of 100 ms.

In Chapter 9 we add a bounce behavior to each ruby and sapphire.

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

createRubySprites: function () {

var RUBY_SPARKLE_DURATION = 100,

RUBY_SPARKLE_INTERVAL = 500,

ruby,

rubyArtist = new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.rubyCells);

for (var i = 0; i < this.rubyData.length; ++i) {

ruby = new Sprite('ruby',

rubyArtist,

[ new CycleBehavior(RUBY_SPARKLE_DURATION,

RUBY_SPARKLE_INTERVAL) ]);

ruby.width = this.RUBY_CELLS_WIDTH;

ruby.height = this.RUBY_CELLS_HEIGHT;

this.rubies.push(ruby);

...

}

},

...

};

7.5.1.2. Flapping Wings and Throbbing Coins

Snail Bait’s bats and bees flap their wings with cycle behaviors, that cycle through images and make it appear as though wings are flapping, as illustrated in Figure 7.5.

Figure 7.5. Bats flapping their wings

Example 7.11 shows how Snail Bait creates bats and bees with cycle behaviors.

Example 7.11. Creating bats and bees with cycle behaviors

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

createBatSprites: function () {

var bat,

BAT_FLAP_DURATION = 200,

BAT_FLAP_INTERVAL = 50;

for (var i = 0; i < this.batData.length; ++i) {

bat = new Sprite('bat',

new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.batCells),

[ new CycleBehavior(BAT_FLAP_DURATION,

BAT_FLAP_INTERVAL) ]);

...

}

},

createBeeSprites: function () {

var bee,

beeArtist,

BEE_FLAP_DURATION = 100,

BEE_FLAP_INTERVAL = 30;

for (var i = 0; i < this.beeData.length; ++i) {

bee = new Sprite('bee',

new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.beeCells),

[ new CycleBehavior(BEE_FLAP_DURATION,

BEE_FLAP_INTERVAL) ]);

...

}

},

...

};

Finally, Snail Bait uses cycle behaviors to make its coins throb. Those behaviors cycle through the two images on the left in Figure 7.6 for blue buttons and the three images on the right for orange buttons.

Figure 7.6. Coin images from Snail Bait’s sprite sheet

Snail Bait’s createCoinSprites() method creates the cycle behaviors associated with the coins, as shown in Example 7.12.

Example 7.12. Cycling through coin images

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

createCoinSprites: function () {

var BLUE_THROB_DURATION = 100,

GOLD_THROB_DURATION = 500,

...

coin;

for (var i = 0; i < this.coinData.length; ++i) {

if (i % 2 === 0) {

coin = new Sprite('coin',

new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.goldCoinCells),

[ ...

new CycleBehavior(GOLD_THROB_DURATION)

]

);

}

else {

coin = new Sprite('coin',

new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.blueCoinCells),

[ ...

new CycleBehavior(BLUE_THROB_DURATION)

]);

}

coin.width = this.COIN_CELLS_WIDTH;

coin.height = this.COIN_CELLS_HEIGHT;

coin.value = 50;

...

this.coins.push(coin);

}

},

...

};

Like sapphires and rubies, Snail Bait’s coins bounce up and down on platforms. In the preceding listing, the associated bounce behaviors have been omitted for brevity.

The createCoinSprites() method alternates between creating gold and blue coins before pushing the newly created coins onto the game’s coin array.

7.6. Combining Behaviors

Individual behaviors encapsulate specific actions such as running, pacing, or sparkling. You can also combine behaviors for more complicated effects; for example, as the snail paces back and forth on its platform, it periodically shoots snail bombs, as shown in Figure 7.7.

Figure 7.7. Snail Bait’s shooting sequence

The snail shooting sequence is a combination of three behaviors:

• paceBehavior

• snailShootBehavior

• snailBombMoveBehavior

paceBehavior and snailShootBehavior are associated with the snail; snailBombMoveBehavior is associated with snail bombs.

Snail Bait creates the game’s only snail in the createSnailSprites() method, as you can see in Example 7.13.

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.SNAIL_CELLS_WIDTH = 64;

this.SNAIL_CELLS_HEIGHT = 34;

this.SNAIL_PACE_VELOCITY = 50;

...

};

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

createSnailSprites: function () {

var snail,

snailArtist = new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.snailCells),

SNAIL_CYCLE_DURATION = 300,

SNAIL_CYCLE_INTERVAL = 1500;

for (var i = 0; i < this.snailData.length; ++i) {

snail = new Sprite('snail',

snailArtist,

[ this.paceBehavior,

this.snailShootBehavior,

new CycleBehavior(SNAIL_CYCLE_DURATION,

SNAIL_CYCLE_INTERVAL)

]);

snail.width = this.SNAIL_CELLS_WIDTH;

snail.height = this.SNAIL_CELLS_HEIGHT;

snail.velocityX = snailBait.SNAIL_PACE_VELOCITY;

this.snails.push(snail);

}

},

...

};

Every 1.5 seconds, the snail’s CycleBehavior cycles through the snail’s images in the sprite sheet, shown in Figure 7.8, and displays each image for 300 ms, which makes it look as though the snail is periodically opening and closing its mouth. The snail’s paceBehavior moves the snail back and forth on its platform.

Figure 7.8. Sprite sheet images for the snail shooting sequence

Snail Bait creates snail bombs with the armSnails() method, which is invoked by the game’s initializeSprites() method, listed in Example 7.14.

Example 7.14. Initializing sprites, revised

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

initializeSprites: function() {

this.positionSprites(this.bats, this.batData);

this.positionSprites(this.bees, this.beeData);

this.positionSprites(this.buttons, this.buttonData);

this.positionSprites(this.coins, this.coinData);

this.positionSprites(this.rubies, this.rubyData);

this.positionSprites(this.sapphires, this.sapphireData);

this.positionSprites(this.snails, this.snailData);

this.armSnails();

},

...

};

The armSnails() method, listed in Example 7.15, iterates over the game’s snails, creates a snail bomb for each snail, equips each bomb with a snailBombMoveBehavior, and stores a reference to the snail in the snail bomb.

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

armSnails: function () {

var snail,

snailBombArtist = new SpriteSheetArtist(this.spritesheet,

this.snailBombCells);

for (var i=0; i < this.snails.length; ++i) {

snail = this.snails[i];

snail.bomb = new Sprite('snail bomb',

snailBombArtist,

[ this.snailBombMoveBehavior ]);

snail.bomb.width = snailBait.SNAIL_BOMB_CELLS_WIDTH;

snail.bomb.height = snailBait.SNAIL_BOMB_CELLS_HEIGHT;

snail.bomb.top = snail.top + snail.bomb.height/2;

snail.bomb.left = snail.left + snail.bomb.width/2;

snail.bomb.visible = false;

// Snail bombs maintain a reference to their snail

snail.bomb.snail = snail;

this.sprites.push(snail.bomb);

}

},

...

};

The snail’s snailShootBehavior shoots the snail’s snail bomb, as shown in Example 7.16.

Example 7.16. Shooting snail bombs

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.snailShootBehavior = { // sprite is the snail

execute: function (sprite, now, fps, context,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

var bomb = sprite.bomb,

MOUTH_OPEN_CELL = 2;

if ( ! snailBait.isSpriteInView(sprite)) {

return;

}

if ( ! bomb.visible &&

sprite.artist.cellIndex === MOUTH_OPEN_CELL) {

bomb.left = sprite.left;

bomb.visible = true;

}

}

};

...

};

Because the snailShootBehavior is associated with the snail, the sprite passed to the behavior’s execute() method is always the snail.

A snail maintains a reference to its snail bomb, so the snailShootBehavior accesses the bomb through the snail. The snailShootBehavior then checks to see if the snail’s current image is the one on the far right in Figure 7.8, meaning the snail is on the verge of opening its mouth; if that’s the case, the behavior puts the bomb in the snail’s mouth and makes it visible.

Shooting the snail bomb, therefore, involves positioning the bomb and making it visible under the right conditions. Subsequently moving the bomb is the responsibility of the snailBombMoveBehavior, shown in Example 7.17.

Example 7.17. Snail bomb move behavior

SnailBait = function () {

...

this.snailBombMoveBehavior = {

execute: function (sprite, now, fps, context,

lastAnimationFrameTime) {

var SNAIL_BOMB_VELOCITY = 550;

if ( sprite.left + sprite.width > sprite.hOffset &&

sprite.left + sprite.width < sprite.hOffset + sprite.width) {

sprite.visible = false;

}

else {

sprite.left -= SNAIL_BOMB_VELOCITY *

((now - lastAnimationFrameTime) / 1000);

}

}

};

...

};

If the bomb is about to disappear off the left edge of the canvas, the snail bomb move behavior makes the bomb invisible; otherwise, the behavior advances the bomb to the left at a constant rate of 550 pixels/second.

![]() Note: Behavior-based games

Note: Behavior-based games

With a behavior-based game, once you’ve got the basic infrastructure implemented, fleshing out the game is mostly a matter of implementing behaviors. Freed from the concerns of the game’s underlying mechanics, such as animation, frame rates, scrolling backgrounds, and so forth, you can make your game come to life by concentrating almost exclusively on implementing behaviors. And because behaviors can be mixed and matched at runtime, you can rapidly prototype scenarios by combining behaviors.

7.7. Conclusion

Behaviors breathe life into sprites, making games come alive. In this chapter, we went from static images of sprites to sprites that do interesting things. Crossing that threshold is significant on two levels. First, at this stage of development, Snail Bait begins to feel like an actual game as the game’s characters reveal their personalities. Second, the introduction of behaviors into the mix results in a significant shift in the actual implementation of the game.

In this chapter you saw how to implement behaviors and attach them to sprites. Behaviors are sometimes tightly coupled to specific sprites such as the runner’s run behavior, whereas behaviors that don’t maintain state can be used simultaneously by many sprites. Some behaviors, such as cycling sprites through sequence of images, can be used in multiple games.

Up to this chapter, we’ve been concerned with the fundamental aspects of implementing video games, such as creating smooth animations, scrolling backgrounds, and drawing sprites. We’ve also discussed user interface aspects, such as fading elements in and out and implementing a loading screen while the game initially loads resources.

From here on, however, our focus in this book shifts primarily to implementing behaviors when we discuss implementing Snail Bait’s gameplay. Almost every aspect of implementing gameplay will involve implementing a behavior and attaching it to the appropriate sprite. In the next chapter, we discuss how to implement a jump behavior for Snail Bait’s runner.

7.8. Exercises

1. Modify the runner’s run behavior so she runs only when she’s on a platform.

2. Modify the snail shoot behavior so the snail shoots a snail bomb once every second.

3. Modify the cycle behavior so it maintains state in the sprites it manipulates instead of in the behavior itself. That change makes the cycle behavior a flyweight. Subsequently, modify Snail Bait so that it creates only one cycle behavior for all the game’s bats. Are there negative consequences for converting the cycle behavior into a flyweight? Explain your answer.