10. Leading with Restraint

“By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.”

—Benjamin Franklin

In every direction that we turn these days, it seems that we hear people talking about the need for more leaders, as well as more effective leadership, in our private and public institutions. The strong desire for enhanced leadership in all aspects of society accelerated after the horrific tragedy of September 11, 2001. For good reason, people have become concerned about how institutions will cope with the extraordinary levels of ambiguity and turbulence in their external environments. Problems seem to be growing more complex, change seems to be happening more quickly than ever before, and many organizations seem ill-equipped to cope with these challenges.

Our institutions need leaders who can motivate people, manage organizational change, and align disparate groups behind a common goal. Decision making is an important facet of leadership, as we have argued in this book. Now more than ever before, leaders need to gather and assimilate divergent perspectives, choose based on incomplete information, test their assumptions carefully, reach closure quickly, and build strong buy-in to facilitate efficient execution. Perhaps most importantly, we hear many people argue that societal institutions need strong, decisive leaders—people who know how to make tough, and sometimes painful and unpopular, choices in a world of ambiguity and discontinuous change.

The recent emphasis on leadership—as well as the concerns about daunting social, political, and economic challenges—do not, of course, represent a completely new phenomenon. Several years ago, in a speech at the Minnesota Center for Corporate Responsibility, Fortune magazine editor-at-large Marshall Loeb offered this perspective based on his interaction with many prominent business executives:

As an editor travels across the country, listening to high executives he hears—over and over—one plaintive question: Where have all the leaders gone? Where are the patrician, eloquent, inspirational Churchills and Roosevelts, the rough-hewn, plain-spoken but ultimately charismatic Harry Trumans and Pope Johns, now that we need them so badly? We are desperate for leaders....Thomas Carlyle had it right I believe: All history is biography—as so all great companies are indeed the direct reflection of their leaders. The leader sets the tone, the mood, the style, the character of the whole enterprise.1

Many people have echoed Loeb’s comments in recent years. Business executives, politicians, and academics all have talked about a “crisis of leadership” in key business and government institutions. It’s more than talk, though; survey data suggest that employees feel a pressing need for more leadership in their organizations. In 2002, Watson Wyatt, a human resources consulting firm, conducted a survey of 12,750 U.S. workers across many industries. Watson Wyatt found that only 45% of respondents “have confidence in the job being done by senior management.”2 Moreover, Watson Wyatt reported in that same year that “less than half of employees (49%) understand the steps their companies are taking to reach new business goals—a 20% drop since 2000.”3 A comparable study conducted in Canada produced similar results.4 Perhaps more disturbingly, a 2002 poll by Workforce Management magazine found that 83% of respondents perceived “a leadership vacuum in their organizations.”5

In a more recent research project, the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) described a significant “leadership deficit” in many organizations. CCL surveyed 2,200 leaders from 15 companies in three countries. The results suggest that the skills that executives possess simply do not meet the needs of these firms moving forward. According to CCL, “Of the ‘top five’ needs—inspiring commitment, strategic planning, leading people, resourcefulness, and employee development—only resourcefulness is considered be a ‘top ten’ skill. This is what CCL calls ‘the current leadership deficit.’”6

What Type of Leaders?

If we need more effective leaders, the question becomes: What type of leaders should organizations seek? Naturally, the so-called management gurus disagree. Jim Collins, arguably the most widely read business writer in the world, conducted a study to determine how and why some companies move from a fairly long period of average financial performance to an era of sustained superior results. He found that only a small set of firms managed to make that leap, and their leaders possessed a distinct set of traits. According to Collins, the CEOs of those firms demonstrated great modesty and humility. They often proved quiet, reserved, and even shy. Collins extols those virtues, and he argues that organizations should seek leaders with those attributes rather than simply chasing individuals who exhibit charisma.7

Tom Peters, another widely read business writer and consultant, disagrees vehemently. He thinks the current tumultuous business climate requires something quite different from the “stoic, quiet, calm leaders” that he hears Collins describe and extol. Peters exclaims, “Would you like to think that a quiet leader will lead you to the promised land? I think it’s total utter bull, because I consider this to be a time of chaos.”8

Peters does not believe that we can identify a single set of personality traits that are associated with superior leadership in all circumstances. He argues that different situations require different types of leaders.9 In fact, many scholars of leadership adopt this point of view. These academics endorse a theory of situational leadership—the notion that fit, or alignment, must exist between a leader’s style and the contextual demands and pressures that he faces.10 In short, institutions must seek a leader who is well suited for the particular challenge that the organization faces at that moment. When making decisions, leaders need to adapt their approach based upon the nature of the problem they are trying to solve.

The Myth of the Lone Warrior

Some people bemoan the focus on leadership at the very top of the organization. They think that people place too much emphasis on the chief executive when it comes to explaining organizational performance. Surely, the business press enjoys crediting charismatic and forceful leaders such as Jack Welch and Lou Gerstner with the success that their firms achieved with them at the helm. Jim Collins criticizes the worship of charismatic and heroic CEOs; he prefers to heap praise on modest, relatively introverted leaders such as Darwin Smith at Kimberly-Clark and Colman Mockler at Gillette. Still, he places a great deal of emphasis on the person in the corner office.11 Lest we forget, these organizations are large and complex, with hundreds of thousands of employees. Yet many people attribute much of these companies’ success to the leadership skills of one person—the heroic CEO.

Leadership scholar Ronald Heifetz wonders whether we expect too much of the person at the top, the individual who holds the most formal authority in our institutions. We believe that the individual at the top will have the answers to all the tough problems facing the organization. Is that really true? Can that possibly be true? Heifetz concludes, “The myth of leadership is the myth of the lone warrior: the solitary individual whose heroism and brilliance enable him to lead the way.”12 Warren Bennis points out that Michelangelo had plenty of help painting the Sistine Chapel; 16 others joined him in painting the ceiling that we all marvel at and praise him for today! Similarly, most firms do not accomplish great things without a team of people supporting and assisting the CEO. Bennis concludes that, in the business and government institutions of today, “The problems we face are too complex to be solved by any one person.”13

Such talk elicits a visceral reaction from many top executives. They argue that firms cannot make critical strategic decisions by committee. Democracy, you will hear, has no place in the executive suite. These individuals believe that the chief executive needs to “take charge” when an organization faces tough problems that require speedy action. The person at the top simply has to make some tough calls on his own. To them, fostering dissent, striving for fair process, and building buy-in among multiple constituencies represent signs of weakness, rather than strength. Some worry that others will perceive a highly participatory approach as a sign of indecisiveness or loss of control. Others believe that such activities will waste precious time and provide competitors the upper hand in the marketplace.

Heifetz points out that many employees reinforce this viewpoint and help perpetuate the myth of the lone warrior. They adopt a very paternalistic view, in which they expect the top authority in the organization to look after them in troubling times and provide the right solutions to vexing problems. Heifetz explains:

In a crisis, we tend to look for the wrong kind of leadership. We call for someone with the answers, decision, strength, and a map of the future, someone who knows where we ought to be going—in short, someone who can make hard problems simple....Instead of looking for saviors, we should be calling for leadership that will challenge us to face problems for which there are no simple, painless solutions—problems that require us to learn in new ways.14

What would we make of a top executive who espoused this philosophy? Imagine if a CEO admitted that he did not know the answer to a pressing problem facing his organization. Imagine if he emphasized the need for a collaborative decision-making process and the requirement to build buy-in before taking action. Would we criticize that individual for not “taking charge” and demonstrating decisive leadership? It is not simply the people in positions of senior authority who perpetuate the myth of the lone warrior, sitting in the corner office making wise choices in a Solomon-like manner. Many of us who sit at a lower level in the organizational hierarchy expect that vision to become reality when our institutions face complex, pressing problems.

Must we espouse an either/or view of the world? Can top executives remain firmly in control of decision making when an organization encounters an exigent situation, yet still provide room for solutions to arise from below and for dissenting voices to be heard? In this book, we have argued that executives can be bold and decisive, while harnessing the collective intelligence of an organization and building buy-in from multiple constituencies.

Two Forms of Taking Charge

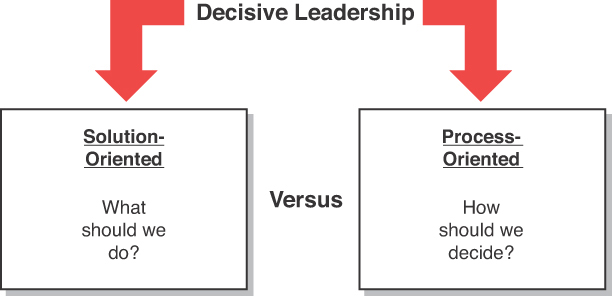

Effective leaders do take charge when confronted with difficult organizational decisions. However, there are two different approaches to taking charge. One kind of leader dives right into the problem, trying to find the best solution. This type of leader focuses on what to do to improve the organization’s performance. A second type of leader takes a step back and focuses at first on how the organization ought to go about tackling the problem. This leader asks the question: What kind of decision process should we employ? This is not to say that the leader does not have an opinion about what to do, but he does not focus exclusively on finding the right solution. Instead, he focuses first on trying to find the right process.

Consultant and researcher David Nadler has argued that many top executives do not distinguish between these two approaches to taking charge. They believe that working with others in a collaborative problem-solving fashion signifies a shift toward “letting the team manage and decide for itself.”15 Nadler tries to clarify this misconception. He believes that leaders can be directive about a decision-making process, while providing subordinates plenty of room to offer divergent perspectives regarding the content of the issue at hand.

When I teach the Bay of Pigs and Cuban missile crisis case studies to executive audiences, I often ask: In which situation would you say that President Kennedy was a more “hands-on” leader? Invariably, nearly half of the class argues that he adopted a more “hands-on” approach in the Bay of Pigs; the others disagree. Who is correct? The answer is straightforward: Both sides are right! In the Bay of Pigs case, Kennedy became very involved in the details of how the invasion would be carried out. In that sense, he appears to have been a “hands-on” leader. However, Kennedy lost control of the decision-making process. He allowed the CIA officials to shape the decision process in a manner that would strongly enhance the probability of achieving the outcome that they desired. In short, Kennedy dove in to find the right solution, but he failed to take charge of the process. Ultimately, his failure to manage the process led to a flawed decision.

During the Cuban missile crisis, Kennedy became more directive about the decision process. He made careful choices about composition, context, communication, and control—the four Cs that together comprise how a leader decides how to decide. Kennedy considered how the deliberations should take place, what roles people should play in the process, and how divergent views should be welcomed and heard. Yet he removed himself from several meetings. He resisted the temptation to micromanage all details of the situation. He offered his advisers some room to state their arguments, to debate one another, and to revise their proposals based upon the critique of others. Kennedy still retained the right to make the final call, and he clearly did not strive for unanimous agreement before moving forward. The president took charge of the decision process, knowing that he would not lose authority or control by offering others an opportunity to express their views. No one perceived Kennedy as weak or indecisive because he stepped back to give others room to state their case before he declared his own views on the matter.

Top executives demonstrate true decisive leadership when they think carefully about how they want to make tough choices rather than by simply trying to jump to the right answer. (Figure 10.1 highlights the distinction between being directive with regard to content vs. process). By deciding how to decide, they increase the probability that they will effectively capitalize on the wide variety of capabilities and expertise in their organization and make a sound decision. Moreover, they enhance the odds of being able to implement the chosen course of action effectively.

Some executives argue that collaborative decision making takes too much time. In some situations, you simply must move very quickly. You don’t have the luxury to give team members ample opportunity to provide input or to cultivate dissent and debate. You can hear them now: “My environment is simply too turbulent and fast paced. I don’t have time for democracy.” Let me offer a simple response to these types of leaders: If you face more time pressure and stress than John Kennedy did during the Cuban missile crisis, then feel free to be an autocrat. Even under the threat of nuclear missiles and a potential third world war, Kennedy found time to gather input and stimulate constructive debate. If he had time to do so, then any leader can shape and design a process that incorporates others’ views and ideas. They can collaborate yet still take decisive action.

Leading with Restraint

The brand of take-charge leadership called for in this book requires a great deal of restraint on the part of top executives. When faced with a complex problem, many executives will have a strong intuitive feeling about what to do, based upon years of experience. That intuition will prove correct in many circumstances, but not all.

To make the most of the expertise and ideas that other members of their organizations possess, leaders need to refrain from pronouncing their solution to a problem before others have had an opportunity to offer their perspectives. They must acknowledge that they do not have all the answers and that their initial intuition may not always be correct. They need to recognize that their behavior, particularly at the outset of a decision process, can encourage others to act in an overly deferential manner. Leaders must understand that the best choices mean very little if various, interdependent units of the organization are not willing to cooperate to execute the decision.

By leading with restraint, individuals in positions of authority recognize that their understanding and knowledge in a particular domain are often bounded, imprecise, and incomplete. They do not begin to tackle a problem by seeking confirmation of their preexisting hypotheses but instead recognize the existence of boundary conditions associated with each of their mental models (that is, their theories may apply under certain conditions but not in all circumstances).16 Restrained leaders implicitly presume that their understanding of a specific domain consists of a set of nascent theories, which may be disproved over time and about which reasonable people may disagree.17 Restrained leaders constantly search and explore for new knowledge, rather than seeking the data and opinions that confirm their preexisting understanding of the world around them.

Let’s return to the 1996 Mount Everest tragedy for a moment. Just before Rob Hall and Scott Fisher made their final push for the summit, accomplished mountaineer David Breashears, the leader of the IMAX film expedition also on the mountain that year, faced a momentous decision. He felt uncomfortable with certain signs that suggested to him a possible deterioration in the weather during his team’s ascent to the top.18 Breashears turned to his team and sought their advice and input. After a dialogue with other expedition members, he chose to turn the team around and head back down to base camp. He recalled how difficult it was to encounter Hall and Fischer heading toward the summit, while he and his colleagues retreated. One of the expedition members remembered feeling a bit self-conscious about the decision to turn back: “We felt a bit sheepish coming down. Everybody is going up and we thought, ‘God, are we making the right decision?’”19 When Breashears came to my class at Harvard Business School a few years ago, he compared his experience on Everest in 1996 to the other expeditions that encountered tragedy. He talked about the need for skilled leaders on mountaineering missions; in his view, the world’s greatest climbers did not necessarily make the world’s best expedition leaders. Toward the end of that discussion, a student asked him what constituted great leadership. Breashears argued that experience, formal authority, and expertise in one’s field did not make someone a great leader. Instead, Breashears spoke of the need to exercise restraint when making decisions:

Some people have tremendous charisma, and they can dominate a room full of people, but all of that does not equal competence. Sure, leaders need to have a vision. But by restraint, I mean the ability to accept others’ ideas without feeling threatened. Those are the people I found to be my role models—not the person who ordered me to go up the mountain, but the person who talked to the team, asking for a dialogue, not feeling threatened by the dialogue, because they still had the ability to make the final decision. Some people can tolerate no dissent. But, if you assemble a great team, don’t you want to hear their ideas?20

Breashears, of course, made a good decision in 1996, and he made that decision in part because he had set the stage for a successful choice. He certainly prepared well for the expedition, in terms of assembling the right equipment and supplies, organizing the logistics of the expedition, planning his group’s acclimatization routine, and thinking through various dangerous scenarios that might unfold on the mountain. Those preparations helped him when conditions became more dangerous on the mountain. However, Breashears prepared for the problems that his team ultimately encountered in another important way. Long before arriving in Nepal, he had put some thought into how he wanted to make critical decisions—about the process he would employ when faced with a tough call that needed to be made. When the signs of deteriorating weather emerged, Breashears took charge by directing a decision-making process that provided him with unvarnished advice and input and that harnessed the vast expertise and knowledge of the other members of his expedition. Breashears succeeded by heeding the advice of Benjamin Franklin: “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.”

Questions, Not Answers

In most business schools, we teach by the case method. We do not lecture our students. We provide a description of a management situation, and we ask students to put themselves in the shoes of the case protagonist, who has an important decision that he needs to make. Students learn inductively in this method of instruction. The professor does not hand the students a set of theories and principles and ask them to apply those ideas to the case study. Instead, the students discuss the issues facing the organization in the case, and principles and hypotheses about how to manage that situation effectively emerge from the class deliberations.21

What do students learn through the case method of instruction? Do they come away with a set of answers about how to act in a specific situation? No, that is not our primary goal. We hope to teach our students how to make decisions rather than provide them a set of prepackaged solutions to various management problems that they may encounter during their careers.

When asked what students learn at Harvard Business School, former Dean John McArthur once said, “How we teach is what we teach.” What did he mean by that? Consider how an instructor behaves in the classroom. He asks questions—lots of them. He does not provide any answers, much to the chagrin of many students. Often, they want to hear the faculty member’s recommended solution to the management problem described in the case. When pressed, most of us simply ask more questions rather than provide answers. A case method instructor leads with restraint. By leading with restraint, we aim to harness the collective intellect in the classroom and to create new knowledge through a process of inquiry and debate. We facilitate and moderate the deliberations. We stimulate dissent and divergent thinking, often employing the techniques described in Chapter 4, “Stimulating the Clash of Ideas,” such as role-play and mental simulation exercises. We try to establish a climate in which conflict can remain constructive. At times, we seek to bring opposing sides together, helping them to find common ground. To gain traction on complex problems, we often break them down into manageable pieces and tackle one aspect of the issue at a time—striving for a series of small wins as we build toward the denouement of a particular class session.

There is an important lesson here for all leaders. Consider again what Peter Drucker once said: “The most common source of mistakes in management decisions is the emphasis on finding the right answer rather than the right question.”22 Indeed, proposing a solution often does not promote novel lines of inquiry, thought, and debate. It can shut down creative thinking or close entire avenues of discussion. By posing incisive questions, leaders can open up whole new areas of dialogue, unearth new information, cause people to rethink their mental models, and expose previously unforeseen risks. Much like a case method instructor, an effective leader uses sharp, penetrating questions to generate new insights regarding complex problems. Those insights become the ingredients necessary to invent new options, probe underlying assumptions, and make better decisions.

For case method instructors, the questions form long before a classroom session commences. Faculty members think carefully about how they want to lead the discussion. We anticipate the key points of debate and conflict. We devise mechanisms to spark divergent thinking. Faculty members consider the personalities in the room. We anticipate points of personal friction. We think about our role in the deliberations and how we will intervene to advance the discussion. In short, we have a plan—albeit a highly flexible one. Great leaders, of course, behave as great teachers. They prepare to decide just as teachers prepare to teach. They have a plan, but they adapt as the decision-making process unfolds. Great leaders do not have all the answers, but they remain firmly in control of the process through which their organizations discover the best answers to the toughest problems.

Endnotes

1. M. Loeb. (1995). “Marshall Loeb on leadership: Ten steps to effective leadership,” Speech at the Minnesota Center for Corporate Responsibility. June 21, 1995.

2. “Growing worker confusion about corporate goals complicates recovery, Watson Wyatt WorkUSA study finds,” Watson Wyatt. Press Release. September 9, 2002.

3. Ibid.

4. “Declining employee confidence in corporate leadership threatens Canadian competitiveness, Watson Wyatt Survey Finds,” Watson Wyatt. Press Release. October 21, 2002.

5. S. Cauldron. (2002). “Where have all the leaders gone?” Workforce Management. December: p. 29.

6. J. B. Leslie. (2009). “The Leadership Gap: What you need and don’t have when it comes to leadership talent” Center for Creative Leadership. www.ccl.org/leadership/pdf/research/leadershipGap.pdf, accessed January 6, 2012.

7. J. Collins. (2001). Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...and Others Don’t. New York: Harper Business. My colleague Rakesh Khurana also has written about the perils that firms face when they pursue charismatic CEOs in the executive search process. See R. Khurana. (2002). “The curse of the superstar CEO,” Harvard Business Review. 80(9): pp. 60–65.

8. J. Reingold. (2003). “Still angry after all these years,” Fast Company. 75: p. 89.

9. T. Peters. (2001). “Rule #3: Leadership is confusing as hell,” Fast Company. pp. 124–135.

10. For instance, see R. Tannebaum and W. Schmidt. (1958). “How to choose a leadership pattern,” Harvard Business Review. 36(2): pp. 95–101; V. Vroom and P. Yetton. (1973). Leadership and Decision Making. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

11. Collins. (2001).

12. R. Heifetz. (1994). Leadership Without Easy Answers. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. p. 251.

13. W. Bennis. (1997). “The secrets of great groups,” Leader to Leader. 3: p. 29.

14. Heifetz. (1994). p. 2.

15. Nadler. (1998). p. 16.

16. Karl Weick has described how individuals engage in sense making. That is, they try to make meaning of previous actions that they have undertaken. An individual’s sense-making process naturally will be influenced by prior life experiences, mental models, etc. Therefore, a leader needs to be wary of relying too heavily on his particular interpretation of a given situation. Others may have made sense of a particular event in a different way. See K. Weick. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

17. For more on this topic, see Edmondson, Roberto, et al. (2005).

18. Breashears’s intuition served him well in this circumstance. Scholars define intuition as pattern recognition based upon experience. In this case, Breashears had many years of experience on Everest, and he spotted a pattern, a set of signals, which reminded him of past instances of looming risk with regard to weather conditions. For more on intuition, see Klein. (1999) and Klein. (2003).

19. Boukreev and Dewalt. (1997). p. 120.

20. D. Breashears. Remarks to Harvard Business School class. February 24, 2003.

21. For more on teaching by the case method, see L. Barnes, C. R. Christensen, and A. Hansen. (1994). Teaching and the Case Method. Third edition. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

22. P. Drucker. (1954). The Practice of Management. New York: Harper Row. p. 351.