7. Teach How to Talk and Listen

“It’s not what you tell them...it’s what they hear.”

—Arnold “Red” Auerbach

On March 27, 1977 five hundred eighty-three people died in the worst accident in aviation history. Two Boeing 747 planes collided that day at Los Rodeos Airport on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. KLM Flight 4805 originated from Amsterdam, and Pan Am Flight 1736 had begun in Los Angeles. Each plane intended to land at Las Palmas, the larger of the two airports in the Canary Islands. However, a terrorist bombing that day had closed Las Palmas, causing flights to be diverted to Tenerife, a much smaller airport not well-suited to serve jumbo jets.1

Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten piloted the KLM flight, which carried two hundred thirty-four passengers and fourteen crew members. Van Zanten had worked for KLM since 1947. The company featured him in its advertising, including in the issue of its in-flight magazine onboard that day. He was the head of the airline’s flight training program, and he trained many of KLM’s other pilots and copilots. In this role, he had spent much more time recently in the simulator than flying charter or commercial flights. Prior to this particular flight, van Zanten had worked exclusively in the simulator for twelve weeks. He had trained the copilot during this time.

Captain Victor Grubbs piloted the Pan Am flight, which carried three hundred eighty passengers and sixteen crew members. The plane represented a slice of aviation history, since it was the first Boeing 747 jet to fly passengers (in January 1970). Grubbs landed at 2:15 that afternoon, roughly one half-hour after the KLM jet arrived at Tenerife. The small airport had limited taxi space, so Grubbs had to park behind the KLM jet. Several other large jets also diverted to Tenerife, which became increasingly crowded.

While waiting for the Las Palmas airport to reopen, Captain van Zanten decided to refuel his plane. He made this decision due to concerns about Dutch law, which had specific restrictions on flight and duty time for crews. The pilot knew that his crew was quite close to its monthly limits. Van Zanten worried that the crew would exceed these legal limits if they did not depart from Las Palmas by seven o’clock that evening. Therefore, he chose to refuel on Tenerife so that he could take advantage of the idle time sitting on the tarmac and then execute a rapid turnaround at Las Palmas. As it turned out, the Las Palmas airport reopened at 2:30 p.m. The Pan Am jet wanted to depart, but it could not get around the KLM plane at the small airport. Refueling took several hours, during which time the Pan Am plane remained parked behind the KLM jet. As the planes sat on the runway, the weather worsened considerably. Visibility became very limited, as low as 300 meters in some locations.

At 4:56 p.m., air traffic controllers directed the KLM jet to proceed down the takeoff runway, perform a 180-degree turn, and await clearance for takeoff. The KLM jet conducted the turn, a rather complex maneuver given the tight space. The controllers asked the Pan Am crew to follow the KLM plane down the runway, take the third exit onto a parallel taxiway, and then come around behind the KLM jet to be next in line for takeoff. The Pan Am crew tried to follow these instructions, but they became confused. Visibility had deteriorated, and the runway exits lacked clear signage. Moreover, the third exit required a very tight 135-degree turn, unlike the more easily navigable 45-degree angle at the fourth exit. For these reasons, the Pan Am crew missed the third exit and continued heading toward the fourth one.

Meanwhile, van Zanten began to throttle his engines, and the plane began to move ahead. Klaus Meurs, the copilot, expressed surprise. He said, “Wait. We don’t have clearance!”2 Van Zanten asked Meurs to obtain clearance for takeoff from the air traffic controllers. The KLM pilot clearly seemed to be in a bit of a hurry to get off the ground, given his concerns about Dutch restrictions on crew flight time. Meurs requested clearance, but the air traffic controllers responded with instructions regarding what to do after the plane had become airborne. The controllers did not provide takeoff clearance, but they did use the word “takeoff” as part of their instructions. Meurs confirmed the details about what to do after becoming airborne, though he did not confirm explicitly that the KLM jet had clearance for takeoff. While Meurs spoke, van Zanten throttled the engines and began to move forward again. Meurs closed his statement with the ambiguous phrase “We’re now at takeoff.” The air traffic controllers, as well as the Pan Am crew, believed that this statement meant the KLM plane was in ready position at the end of the runway, awaiting clearance for takeoff. The controller responded, “OK. Stand by for takeoff. I will call you.” The Pan Am crew responded firmly, “We are still taxiing down the runway.” Unfortunately, these important statements became difficult, but not completely impossible, to hear inside the KLM jet because of radio interference that impeded clear transmission. Meanwhile, the Pan Am plane had not yet reached the fourth exit.

At this point, the air traffic controllers asked the Pan Am crew to report when they had exited the runway. The Pan Am crew replied, “OK. We will report when we are clear.” The KLM flight engineer, William Schreuder, heard this exchange and became concerned. He asked van Zanten rather tentatively, “Did he not clear the runway, then?” The captain responded, “What do you say?” Schreuder asked again, “Is he not clear, that Pan American?” The captain heard and understood the awkward question, and he replied emphatically, “Oh yes.” He believed that the runway was clear, and he proceeded with takeoff. Schreuder did not question the captain any further. First officer Meurs also offered no objection. Because of the extremely low visibility, the KLM crew could not see the Pan Am jet ahead of them on the runway.

Inside the Pan Am cockpit, the crew discussed van Zanten’s apparent anxiousness to depart. Captain Grubbs said, “Let’s get the hell out of here.” Flight engineer George Warns noted that van Zanten appeared anxious and said, “After he’s held us up for all this time, now he’s in a rush.” Moments later, the Pan Am crew noticed the KLM jet headed right toward them. Grubbs yelled, “There he is...look at him! Goddamn, that son of a bitch is coming!” Copilot Robert Bragg shouted, “Get off! Get off! Get off!” Grubbs tried feverishly to turn off the runway.

At the very last moment, van Zanten saw the Pan Am jet on the runaway in front of him and tried to avoid the crash. The KLM jet became airborne, but its fuselage scraped the top off the Pan Am plane during liftoff. The KLM jet slammed back into the ground, killing everyone onboard. The Pan Am plane burst into flames. Only fifty-six passengers and five crew members survived.

What went so terribly wrong in this case? Clearly, the crowded conditions at the small airport, poor weather, air traffic control’s lack of experience in working with 747 jets, and the KLM pilot’s anxiousness to depart all contributed to the disaster. Beyond that, though, University of Michigan Professor Karl Weick argues that “The Tenerife disaster was built out of a series of small, semi-standardized misunderstandings.”3 For instance, much confusion surrounded the use of the word “takeoff” during communications between the controllers and the KLM crew. Air traffic control never believed that it had granted clearance for takeoff. The Pan Am crew also did not believe that clearance had been given. Throughout the communication, the parties did not always seek or provide confirmation from each other in unambiguous terms; they used casual, nonstandard language at times. People assumed the consent of others without adequate verification. Moreover, van Zanten had spent a great deal of time in the simulator, where a training pilot often issues takeoff clearance himself, rather than communicating with air traffic control, as on a normal flight. Thus, van Zanten may not have been recently accustomed to seeking and receiving confirmation on key communications.

The evidence suggests that the culture of the cockpit contributed to the tragedy as well. The copilot and the flight engineer demonstrated a great deal of deference to the captain, as was customary at the time. Neither one spoke up as forcefully as they could have to question the captain’s decision to commence takeoff. Weick argues that stress often causes hierarchy and authority to become more salient to people. In other words, as the stress levels rose during that afternoon, the KLM crew behaved less and less as a team of equals. Open communication and candid dialogue suffered as a result. Weick describes the condition in the cockpit during those final moments before the crash as pluralistic ignorance. He explains, “Pluralistic ignorance applied to an incipient crisis means I am puzzled by what is going on, but I assume no one else is, especially because they have more experience, more seniority, higher rank.”4 In those final moments, he posits that the other crew members may have been thinking, “Surely the captain knows that the runway may not be clear.”5

Crew Resource Management Training

During the 1970s, aviation safety experts became quite concerned after a series of major accidents such as the Tenerife tragedy. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) hosted a workshop on aviation safety in 1979 to discuss this issue. Research presented at this workshop demonstrated that mechanical failure did not represent the principal cause of air transport accidents. Moreover, most crashes did not occur because the crew lacked the appropriate technical skills and capabilities. The researchers focused instead on deficiencies related to interpersonal communication, teamwork, decision-making, and leadership. The workshop participants identified the need for a training program to develop these cognitive and interpersonal skills. Airlines began to implement Crew Resource Management (CRM) training in the years that followed.6 More recently, others have adopted this approach, including the military, the merchant navy, the nuclear power industry, firefighters, health care organizations, and offshore oil and gas companies. Many organizations have reported substantial safety improvements as a result of applying CRM techniques.7

CRM strove to change the culture of flight crews. Robert Helmreich and Clayton Foushee described the ethos of pilots in decades past:

“In the early years, the image of a pilot was of a single, stalwart individual, white scarf trailing, braving the elements in an open cockpit. This stereotype embraces a number of personality traits such as independence, machismo, bravery, and calmness under stress that are more associated with individual activity than with team effort... Indeed, in 1952 the guidelines for proficiency checks at one major airline categorically stated that the first officer should not correct errors made by the captain.”8

The captain possessed tremendous authority and status. The crew learned not to question the pilot’s judgment. According to Robert Ginnett of the Center for Creative Leadership, a humorous sign found on the bulletin board of a commercial airline revealed fundamental attitudes regarding the crew’s relationship with the captain. The sign read: “The two rules of commercial aviation—Rule 1: The captain is ALWAYS right. Rule 2: See Rule 1.”9

CRM set out to change the culture and attitudes of flight crews. The training emphasized teamwork over individualism, and it focused on interpersonal communication skills. Copilots and flight engineers learned how to be assertive, yet respectful, when they believed that a situation had become unsafe. Captains learned to invite input from other crew members, beginning with the statements they made during the preflight briefing. Ginnett describes how one highly effective captain spoke to his crew: “I just want you guys to understand that they assign the seats in this airplane based on seniority, not on the basis of competence. So anything you can see or do that will help out, I’d sure appreciate hearing about it.”10

Chapter 1, “From Problem-Solving to Problem-Finding,” mentioned that Captain Al Haynes attributed the remarkable emergency landing of United Flight 232 in Sioux City, Iowa to the crew’s CRM training. In a speech to NASA two years after that incident, Haynes said:

“The preparation that paid off for the crew was something that United started in 1980 called Cockpit Resource Management... All the other airlines are now using it. Up until 1980, we kind of worked on the concept that the captain was THE authority on the aircraft. What he said, goes. And we lost a few airplanes because of that. Sometimes the captain isn’t as smart as we thought he was... Why would I know more about getting that airplane on the ground under those conditions than the other three (crew members)? So, if I hadn’t used CRM, if we had not let everybody put their input in, it’s a cinch we wouldn’t have made it.”11

The following sections describe some of the key cognitive and interpersonal skills involved in CRM and explain how any organization can develop its employee capabilities in these areas. To begin, it helps to teach people about the types of communication errors that commonly take place.

Communication Errors

The International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) has developed a detailed document for describing how firefighters can adopt CRM practices.12 In that work, they identify errors that people sending and receiving messages often make. Sender errors include omitting key information and/or providing biased information. Omissions may occur because the speaker is in a hurry, or perhaps he or she has made assumptions about what the listener already knows. Senders also make the mistake of ignoring the impact of nonverbal cues such as body language, facial expressions, eye contact, and gestures. Senders may speak too quickly, not giving the listeners time to digest what they have heard and to ask clarifying questions. When I was learning to teach, Professor Martin Feldstein once advised me, “You have to be comfortable with silence on occasion when you lecture. Students need time to formulate questions or craft responses to your queries.”13 Along these same lines, speakers often forget to vary their tempo; slowing down and/or changing one’s intonation can help emphasize key ideas. Senders sometimes forget to repeat important messages; they assume that others heard and understood them the first time they described a thought or made a suggestion. Finally, speakers often assume that silence equals assent; when others do not object to a particular statement or request, we automatically conclude that they must support us.

Individuals receiving messages make a number of mistakes that impede effective communication as well. Often we make up our minds before others have spoken. Sometimes we begin thinking about how to respond before the speaker has completed his or her thought. We make many assumptions about the meanings of particular words and ideas, often jumping to the conclusion that the speaker is employing the same language system to which we are accustomed. We attribute the wrong intent to others’ messages, perhaps because that helps us explain to ourselves why they disagree with our views. Receivers miss nonverbal signals, just as senders often underemphasize their importance. Listeners fail to ask for clarification and confirmation. As we saw in the Tenerife disaster, confirming what you have heard proves critical at times to avoid serious misunderstandings. Finally, receivers often choose to multitask, causing them not to hear key words and statements. As you watch a management meeting in which everyone keeps checking their personal digital assistants under the table, you know that communication breakdowns are quite likely to occur.14

Improving Interpersonal Communication

How, then, can we improve communication within our organizations so that we do not have leaders and team members behaving as the crew did during the Tenerife disaster? Leaders clearly must change their own behavior and improve their own communication with others. Moreover, organizational leaders must become teachers; they have to take responsibility for developing the interpersonal communication skills of their subordinates. If necessary, leaders may bring in outside experts, as the airlines have done with CRM trainers. Above all else, senior leaders must model good behavior for everyone else in the enterprise.

To begin, we must focus on the importance of that first meeting when a team comes together to launch a project. That meeting represents an opportunity to begin the team formation process—to clarify goals, norms, and responsibilities. Airlines call these meetings “preflight briefings.” We also should pay close attention to the “handoffs” that occur in our organizations—those times when a task or project passes from one unit of the enterprise to another. Problems often occur during these handoffs. Poor communication causes critical information to not pass from one group to another, and larger problems begin to build. Finally, leaders must take the responsibility to teach their people how to speak up assertively when they spot problems, as well as how to listen effectively when someone comes forward with bad news.

Briefings

As former U.S. Airways pilot Kelly Ison says, “good communication begins with an effective crew briefing before the first leg of a series of flights that we embark upon together over four or five days.”15 That briefing helps bring together the team, outline the shared goals and objectives, and establish the norms of behavior. Ison points out that many errors and near-misses happen on the first leg of the first day during which a crew flies together. Thus, he advocates the use of that briefing to build familiarity with one another and to clarify the team structure to avoid such mishaps.

The pilot ensures that everyone understands their roles and responsibilities during the preflight briefing.16 The team reviews the timing and sequence of key tasks that must be accomplished, as well as the distribution of the workload among crew members. An effective briefing includes a discussion about the types of unplanned events that might occur, and how the team will approach these situations. Perhaps most importantly, Ison contends that the captain must open the avenues of communication during that briefing. For instance, Ison suggests that the pilot tell the crew, “Come to me if you see problems or unexpected events. I’m here and want to know if you believe a problem exists.” Throughout the briefing, the team gets to know one another, and they begin practicing the communication techniques they will need to execute a successful flight.

Military aviators emphasize the critical importance of preflight briefings as well. Former F-15 pilot James Murphy argues that “The mission is the brief; the brief is the mission. The two are inextricably linked in that pilot’s mind, and he or she would no more fly a mission without a brief than drive to work naked.”17 As you might expect from a soldier, Murphy argues that briefings should be precise. He explains that leaders should “chair-fly” the mission prior to a briefing in order for it to be successful. By chair flying, he means that the leader should sit down and visualize how the mission will unfold. Seek out potential flaws in the mission, as well as unplanned events that might affect the team. Anticipate questions that your team may ask you about the goals and plans for the mission. Murphy concludes, “I can’t tell you how many times I realized there was a mistake in the execution phase by just chair-flying the mission before putting the briefing on.”18 Interestingly, people in other professions employ such visualization techniques prior to bringing a team together to accomplish a challenging goal. For instance, accomplished mountaineer David Breashears explains that he spends weeks before an expedition “envisioning every possible scenario that might unfold on the mountain.”19 Then he reviews key scenarios with his team at the outset of the expedition.

What’s happening with these “chair-flying” activities? Murphy and Breashears have visualized potential problems and have shared these thoughts with their team. That up-front communication helps others spot those problems if they arise down the road. Chair-flying the mission and visualizing possible pitfalls sends a strong message to your team that you do not expect a perfect implementation process; you are prepared for a myriad of errors and disruptions. Having heard their leaders discuss these scenarios, individuals feel more comfortable coming forward later to surface a problem they have spotted.

Do companies launch projects in this manner? Clearly, they often do not. We bring together a group of talented people, and we expect them to perform well as a team. Like airline flight crews, we sometimes bring teams together whose members do not know one another, or who have not worked together on a regular basis. We do not always take the steps required to lay a solid foundation for that team at the outset.20 Organizational teams need to develop their own version of the preflight briefing. They must use these launch meetings to clarify shared goals and norms, as well as each member’s roles and responsibilities. Team members should discuss how they will communicate with one another, and the leader must take special care to establish an atmosphere of candid dialogue.

Handoffs

Health care organizations have discovered that effective “handoffs” prove critical to reducing medical accidents. Consider what happens when a patient has surgery. The operating team must hand off the patient to the group working in the postoperative recovery area. After some time, that group must hand off the patient to floor nurses who will care for the individual during his or her stay in one of the hospital’s beds. Successful care of that patient requires that crucial information pass from one group to the other during this process. In the past, though, many medical accidents occurred because communication broke down; hospitals fumbled the handoffs.21

Today, hospitals work diligently to ensure that clear and concise briefings occur at the time of these handoffs. For instance, at Children’s Hospital in Boston, the staff in the postsurgical recovery area calls the floor nurse prior to transferring the patient to a bed. The recovery nurse explains the individual’s condition in detail. Then the recovery nurse typically accompanies the patient to his or her room and conducts an in-person briefing with the floor nurse. Together, they review the patient’s chart and discuss what should take place moving forward. They also talk about what issues or problems might arise, and what the floor nurse should “keep an eye on” moving forward.22

Like these hospitals, business enterprises must think about where the critical handoffs take place in their organization. When and where do key projects and tasks shift from being the chief responsibility of one unit to another? What information is most likely to fall through the cracks? How should these briefings take place to ensure a smooth handoff?

A few simple communication strategies help make handoffs more successful. First, communicate face-to-face whenever possible, thereby enabling the use of nonverbal cues and interactive questioning. Second, provide written information in advance of the face-to-face meeting so that the receiving party can prepare for the handoff. Third, avoid interruptions while striving to keep the briefing as concise as possible. Fourth, bring teams together to brief one another, rather than relying on a representative from each group to execute the handoff; this reduces the potential for miscommunication by removing that extra step in the process. Finally, each party should confirm their interpretations of what they have heard.23

Speaking Up Effectively

Sometimes problems do not surface in organizations because individuals do not know how to speak up effectively. People try to communicate their concerns, but they cannot seem to get anyone to listen. They may pose a question quite tentatively, as the flight engineer did in the final moments of the Tenerife tragedy. Perhaps individuals manage to get the ear of a senior executive, but they fail to persuade. Leaders have a responsibility to coach and teach their people how to speak up assertively, yet respectfully, when they spot a problem or have a dissenting view. Speaking up requires skill, not just courage.

Crew Resource Management (CRM) expert Todd Bishop of the Error Prevention Institute has developed a five-step process for how to speak up assertively when you see a problem.24 To begin, you should address the person to whom you are expressing your concerns by name. Then, you must express your concern concisely and clearly, using an “owned emotion.” By that, Bishop means that you should explain how the problem has made you think and feel. Use the first person, rather than projecting your emotions onto others. For instance, you might say, “I have a bad feeling because...” State the problem as it appears to you: “From my perspective, it looks as if...” Next, be sure to propose one or more alternative solutions to the problem. As the old saying goes, “Don’t tell me about the flood. Build me an ark.” In this case, Bishop advocates describing why you perceive a flood taking place and then explaining how an ark might solve that problem. Putting forward a range of possible solutions helps signal your willingness to take responsibility for helping address the issue. You have not simply dumped the problem in someone else’s lap. In so doing, you may reduce the defensiveness of the other party and minimize the likelihood of interpersonal conflict. Finally, close your assertive statement with an attempt to secure agreement from the other party. One might ask, “Do you concur with my assessment?” That question puts the onus on the other party to respond to your statement of concern.

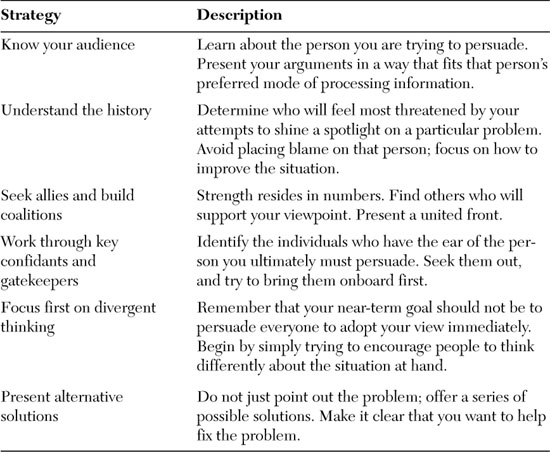

Speaking up requires more than crafting the right series of statements, though. In large, complex organizations, individuals must pay close attention to social and political dynamics. They need to find a way to gain access to key decision-makers and to build support for their viewpoints. To begin, individuals must know their audience. Who are you trying to persuade? How do they think and make choices? What constitutes evidence to them? Some decision-makers rely heavily on data and formal analysis. Others depend on their intuition a great deal. Emotions play a major role for some decision-makers, but less so for others. When speaking up about a potential problem, individuals must understand these distinctions. If a key decision-maker proves highly analytical, you should not simply argue that your “gut” tells you that a problem exists. Marshaling data and conducting methodical analysis will prove more convincing. Individuals also must understand the historical background of the key decision-makers. Is this project “their baby”? Will they feel threatened if you argue that a problem exists? If so, individuals must take great care to avoid placing blame. Focus on the solution, and take ownership for helping resolve the issue.

Sometimes individuals cannot expect to persuade others that a problem exists on their own. They need help. Seeking allies and building coalitions are effective strategies in many situations. Individuals must remember that strength resides in numbers, particularly when one holds a dissenting view. A group may marginalize or dismiss the concerns of a lone voice trying to challenge the majority’s perspective. However, if two or more people chime in together, the majority may find it much more difficult to dismiss these concerns with ease.25

When trying to present unwelcome news or a dissenting viewpoint, it helps to know who has influence with the senior executive you want to persuade. Most leaders rely on a trusted confidante at times for counsel and advice. That confidante serves as a useful sounding board.26 He or she has the senior executive’s ear. Others may serve as key gatekeepers who manage the flow of information to a senior leader. If an individual wants to be heard, particularly when bringing forth bad news, he or she must determine who these confidantes and gatekeepers are. One must attempt to bring these individuals onboard so that they can help make the case that a problem truly exists.

When speaking up as a dissenting voice, individuals must remember that their goal need not be to change people’s minds immediately. Simply expressing an alternative perspective often causes others to think differently about a particular situation. Psychologists Charlan Nemeth and Julianne Kwan have shown that “Exposure to persistent minority views causes subjects to reexamine the issue and to engage in more divergent and original thought.”27 In an interesting experiment, they exposed individuals to a series of blue-colored slides, while a confederate purposefully judged these blue slides to be green. Then the researchers told the subjects about the results of prior studies (the results were concocted for purposes of the experiment). They informed some subjects that the confederate’s judgment represented the majority viewpoint in earlier studies, and they told the others that the confederate’s judgment represented the minority viewpoint in prior research. The researchers wanted to establish a perception on the part of the subjects that they were opposed by either a majority or a minority. After showing the colored slides, they asked all subjects to provide a series of word associations in response to the words “blue” and “green.” Amazingly, the subjects who were made to believe that the confederate’s judgment represented the minority viewpoint actually produced a higher quantity of word associations. Moreover, those associations were more original! Nemeth and Kwan found that opposition from a majority leads to more conventional thought. However, they concluded, “It is opposition by a minority that encourages originality, the use of varied strategies, and results in the detection of both more solutions and more novel solutions.”28 Amazingly, the researchers demonstrated that exposure to a minority view on a particular topic can stimulate originality on a subsequent, related task.

Other studies have confirmed these findings. When someone offers a dissenting view, it may not change the minds of the majority immediately. However, it tends to stimulate more divergent thinking. That creative thought may help others ultimately agree that a problem exists with the current course of action. When people come to that conclusion for themselves, they take ownership of the situation and commit to resolving the problem.29 Table 7.1 summarizes the strategies that individuals can employ to speak up more effectively.

Winston Churchill, one of history’s greatest orators, once said, “Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak; courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen.” When people come forward with problems and bad news, it helps if others listen genuinely and effectively to their concerns. Good listening must be active; you must interact with the speaker through questions, statements, and nonverbal cues. You must show them that you care about what they are saying and that you want to understand them more clearly.

Good listening begins with engagement. When students sit passively in a classroom, they act like empty vessels, hoping that the professor will fill them with knowledge. Much more learning takes place when professor and student engage interactively. Good listeners ask clarifying questions. They paraphrase what they have heard and play it back to test for understanding. They take notes, using both words and pictures/diagrams to record and synthesize what they have heard. Good listeners let a speaker know when they are confused, or when they need more information on a particular point.

Listeners must exercise a good deal of restraint, though. They have to refrain from jumping to conclusions based on a few early statements made by the speaker. That initial judgment may cause them to dismiss much of the rest of what the speaker has to say. Ralph Nichols describes how he encourages students to listen more effectively:

“Listening efficiency drops to zero when the listeners react so strongly to one part of the presentation that they miss what follows. At the University of Minnesota we think this bad habit is so critical that, in the classes where we teach listening, we put at the top of every blackboard the words: Withhold evaluation until comprehension is complete—hear the speaker out. It is important that we understand the speaker’s point of view fully before we accept or reject it.”30

Distractions prove a major problem for many listeners. Turn off the phone and ignore the email for a few moments. Give the speaker your undivided attention. Avoiding distractions not only improves understanding, it also is the courteous thing to do. As someone speaks to you, make eye contact. Use gestures and body language to show that you are processing and reacting to what you have heard.

Nichols points out that people think faster than they speak. People speak one hundred to one hundred twenty-five words per minute, but they can think at four to five times that rate. The most effective listeners take advantage of that difference. They do not allow themselves to daydream. Instead, they begin to process what they have heard. They summarize it occasionally for themselves, and they try to identify the major themes being presented. They synthesize multiple ideas and seek connections among various points that have been made. They even try to anticipate what the speaker will say next. This active thought process helps ideas sink in deeply, and it improves recall in the future.

Finally, the best listeners do not spend a great deal of time worrying about how they will respond when the speaker is done. Poor listeners are obsessed with rehearsing what they will say when the other party stops talking. At times, the speaker may be only a short way through his or her statement, and the so-called listener already has decided how to respond. In business school case study discussions, the most frustrating episodes occur when a student puts forth a rehearsed comment she has prepared prior to arriving at class. She jumps into her dialogue and then wonders why the others seem dismayed by her comment, which does not fit into the flow of the discussion.

Train Teams, Not Individuals

In a recent special feature on leadership development, Fortune magazine focused on the best practices of companies known for building the capabilities of their people. Senior editor Geoffrey Colvin writes that the best companies for building leaders “develop teams, not just individuals.” He quotes Jeffrey Immelt, CEO of General Electric:

“‘At the GE I grew up in, most of my training was individually based,’ says Immelt. That led to problems. He’d attend a three-week program at Crotonville, but back at work ‘I could use only 60% of what I’d learned because I needed others—my boss, my IT guy—to help with the rest.’ And maybe they weren’t onboard. Now GE takes whole teams and puts them through Crotonville together, where they make real decisions about their business. Result: ‘There’s no excuse for not doing it.’”31

Many organizations do train their people to communicate more effectively. They bring together individuals from various parts of the organization, and they try to develop their capabilities. Often, this training takes place in a leadership development program, perhaps for individuals who have been designated as “high potentials.” However, many organizations make a crucial mistake as they design these developmental opportunities. They fail to occasionally bring together intact organizational teams to learn how members can communicate more effectively with one another. Some training can be done at the individual level, but the development of interpersonal communication capabilities often works best within a working group. Then the entire team can reflect on their past experiences, learn about ideas and concepts together, and practice new techniques with one another. That practice can take place in a safe setting with facilitators who can offer rapid and constructive feedback. The team then can put the new techniques to work when they have key issues to address back on the job.

As a leader, you must take responsibility for honing your own communication skills and for developing your people’s capabilities. Surely you will hear from skeptics who doubt the efficacy of communication training. When the naysayers emerge, remind them of the Tenerife tragedy. Recount to them how aviation experts developed Crew Resource Management (CRM) techniques. Tell them how industry after industry has reported marked safety improvements thanks to CRM practices. Finally, remind them of Captain Al Haynes, who believes that CRM saved many lives on that day in Sioux City, Iowa, when he and his crew executed a remarkable crash landing of United Flight 232. As Haynes said, “If I hadn’t used CRM...it’s a cinch we wouldn’t have made it.”32

1 This account of the Tenerife disaster draws on several sources: See Weick, K. (1990). “The vulnerable system: An analysis of the Tenerife air disaster.” Journal of Management. 16(3): 571–593; Job, M. (1994). Air Disaster: Volume 1. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications. In addition, see the following website for information: http://www.super70s.com/Super70s/Tech/Aviation/Disasters/77-03-27(Tenerife).asp.

2 All the quotes in this section come from the original transcripts of the cockpit voice recorders. See the following website for the transcripts: http://www.pan-american.de/Desasters/Teneriff2.html.

3 Weick, K. (1990). p. 582.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Weiner, E. L., B. G. Kanki, and Robert L. Helmreich. (1995). Cockpit Resource Management. London: Academic Press.

7 Flin, R., P. O’Connor, and K. Mearns. (2002). “Crew resource management: Improving team work in high reliability industries.” Team Performance Management. 8:(3/4): 68–78.

8 Helmreich, R. and H. C. Foushee. (1995). “Why crew resource management? Empirical and theoretical bases of human factors training in aviation.” In R. Flin, P. O’Connor, and K. Mearns (eds.). Cockpit Resource Management. (3–45). London: Academic Press. The quote can be found on page 4.

9 Ginnett, R. (1995). “Crews as groups: Their formation and their leadership.” In R. Flin, P. O’Connor, and K. Mearns (eds.). Cockpit Resource Management. (71–98). London: Academic Press. This quote can be found on page 82.

10 Ginnett, R. (1995). This quote can be found on page 90.

11 http://yarchive.net/air/airliners/dc10_sioux_city.html.

12 Crew resource management: A positive change for the fire service. (2003). International Association of Fire Chiefs. Fairfax, Virginia.

13 During my time in graduate school, I taught Economics 10, the introductory micro- and macroeconomics course at Harvard College. The course head was Professor Martin Feldstein, the distinguished economics professor and former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers in President Ronald Reagan’s administration. Each year, he brought together the new graduate student teaching fellows for a weekend of training. I attended the first year as a trainee and in subsequent years as a trainer. Professor Feldstein always shared these words with incoming teachers.

14 Crew resource management: A positive change for the fire service. (2003). International Association of Fire Chiefs. Fairfax, Virginia.

15 Interview with Kelly Ison. He is a former U.S. Airways pilot. At the time of the interview in late 2006, Ison served as the President of Europe for Tomcat Global.

16 The following information comes from the interview with Ison as well as from Airbus’s booklet on flight operations briefings, which can be found at the following URL: http://www.airbus.com/store/mm_repository/safety_library_items/att00011205/media_object_file_FLT_OPS-CAB_OPS-SEQ01.pdf.

17 Murphy, J. (2005). Flawless Execution. New York: Harper Collins. p. 93.

18 Ibid, p. 95.

19 David Breashears first mentioned this to me over lunch when I was working on my case study of the 1996 Mount Everest tragedy in 2002. Breashears and I have spoken numerous times over the past six years, and he has been kind enough to visit my classes several times. He has shared some keen insights into leadership based on his experience as an accomplished mountaineer and filmmaker.

20 Hackman, R. (2002). Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

21 Powell, S. and R. Hill. (2006). “My copilot is a nurse: Using crew resource management in the OR.” AORN Journal. 83(1): 178–206.

22 My daughter Celia had a series of skin graft surgeries in 2006–2007 to address a large nevus on her ankle. Dr. Richard Bartlett performed the surgeries, and he did a remarkable job. These observations come from my time at the hospital.

23 http://www.airbus.com/store/mm_repository/safety_library_items/att00011205/media_object_file_FLT_OPS-CAB_OPS-SEQ01.pdf; Powell, S. and R. Hill. (2006).

24 Crew Resource Management: A Positive Change for the Fire Service. (2003). International Association of Fire Chiefs. Fairfax, Virginia.

25 Many people believe that political behavior is detrimental in organizations. However, as Joseph Bower once wrote, “Politics is not pathology. It is a fact of large organization.” Bower, J. (1970). Managing the Resource Allocation Process. Boston: Harvard Business School Division of Research. p. 305. Kathleen Eisenhardt and L. Jay Bourgeois found that political behavior—defined in terms of activities such as withholding information and behind-the-scenes coalition formation—leads to less effective decisions and poorer organizational performance. See Eisenhardt, K. and L. J. Bourgeois. (1988). “The politics of strategic decision making in high-velocity environments: Toward a midrange theory.” Academy of Management Journal. 31(4): 737–770. However, other studies show that certain forms of political behavior can enhance organizational performance. For instance, Kanter, Sapolsky, Pettigrew, and Pfeffer each have conducted studies that show that political activity such as coalition-building can prove helpful in building commitment and securing support for organizational decisions. See Kanter, R. (1983). Change Masters. New York: Simon and Schuster; Sapolsky, H. (1972). The Polaris System Development: Bureaucratic and Programmatic Success in Government. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; Pettigrew, A. (1973). The Politics of Organizational Decision Making. London: Tavistock; Pfeffer, J. (1992). Managing with Power. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Why the discrepancy in these studies? It appears that the results depend on precisely how scholars define politics, as well as precisely how managers employ political tactics in organizations.

26 Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). “Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments.” Academy of Management Journal. 12: 543–576.

27 Nemeth, C. and J. Kwan. (1985). “Originality of Word Associations as a Function of Majority vs. Minority Influence.” Social Psychology Quarterly. 48(3): 277–282. This quote is from page 277.

28 Ibid, p. 282.

29 Charlan Nemeth has conducted a whole series of studies on this subject. For more information on this stream of research, see Nemeth, C. J. (2002). “Minority dissent and its ‘hidden’ benefits.” New Review of Social Psychology. 2: 21–2.

30 Nichols, R. (1960). “What can be done about listening.” The Supervisor’s Notebook. 22(1). For a copy of this article, see the following URL: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~acskills/docs/10_bad_listening_habits.doc.

31 Colvin, G. “How top companies breed stars.” Fortune. September 20, 2007.