3. Marketing Movies: Building Wannasee, Haftasee, and Mustsee

Samuel Taylor Coleridge called drama “that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.” Most modern movie producers would probably call the act of financing and making a movie the willing suspension of financial sanity. With blockbusters running well into the multiple hundreds of millions of dollars, making a movie is a seriously risky business, full of potential pitfalls at every turn.

For producers and studios, movie marketing is the hedge against disaster and the support system for success. Marketing is the engine that drives public perception, creating “wannasee,” luring people into the theaters and dollars into the box office.

Big Numbers for the Big Screen

Of all the platforms, the revenue for movies—the box office—may be the most misleading. When you stack up those ticket sales against those for other forms of entertainment, the revenue may not seem very impressive. But movies attract far larger audiences: annual movie attendance is estimated at 1,358 million versus 359 million for theme parks and 131 million for sports.1 Given the far higher participation, there is a much larger audience for all the associated merchandising and licensing that flows from movies, not to mention the downstream revenue from the “windowing” that occurs after first release2: premium cable, home video (DVR), Netflix, streaming in Hulu, HBOGo, basic cable, U.S. network TV, Red Box, airplanes, cruise ships—more lives than your average cat.

1 Motion Picture Association of America (Rentrak 2012 research).

2 Windowing used to follow a fairly traditional schedule, spread across many months, with international release repeating the process outside the U.S. However, with digital piracy now a primary concern, windows have been compressed to a point of overlap in order to get the movie out as quickly as possible. Movies may now have a simultaneous release all over the world, with home video and streaming occurring quickly thereafter.

So in the world of entertainment, movies are still the Big Dog.

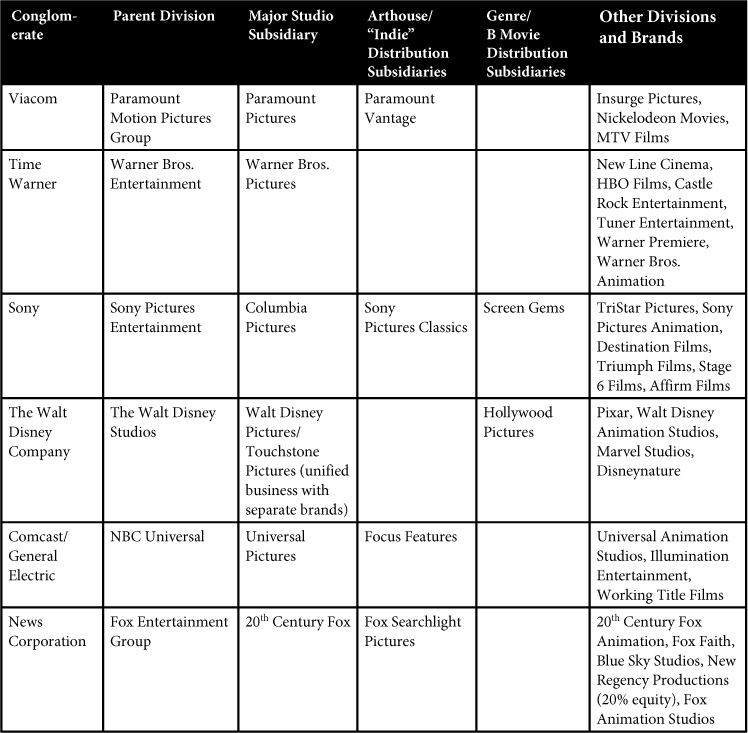

Movies are a marketing powerhouse. The so-called Big Six studios alone—outlined in Exhibit 3-1—average over $700 million per year on their marketing spend.3 A conservative estimate for all other movie marketing, including independent films and home video, comes to $4.5 billion per year.4 Add the marketing attached to all the associated licensing and merchandising deals for these films, and the number does nothing but climb.

3 PwC Global Entertainment and Media Outlook: 2012–2016, www.pwc.com/outlook.

4 Marich, Robert, Marketing to Moviegoers: A Handbook of Strategies and Tactics, Third Edition, Southern Illinois University Press, 2013.

Exhibit 3-1 The “Big Six” Studios5

5 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Major_film_studio.

The cost of advertising a mainstream movie has risen for blockbusters, from an average of $35 million in 2005 to over $50 million in 2012.6 This includes network, cable, and satellite television; national and local newspapers; billboards; radio; online; and tie-in advertising. When a blockbuster goes global, that figure can rise to $70 million for publicizing and distribution.7

6 PwC Global Entertainment and Media Outlook: 2011–2014, www.pwc.com/outlook.

7 “Movie Ticket Prices Hit All-Time High in 2011,” The Hollywood Reporter, February 9, 2012.

All that spending—on marketing as well as production—creates a huge risk, and that risk is exacerbated by a rule of thumb known as the 6-2-2 formula, which states that out of a slate of ten yearly releases, six movies lose money, two break even, and two make the money that covers all the aforementioned losses. This is true for movies in general, both produced by the studio and independent films.8 Although marketing is critical for all ten films, it will put those crucial two over the top.

8 Please note: We use the word “film” interchangeably with “movie,” even though movies are now primarily digital transmissions—bye-bye 35mm film.

You will note from Exhibit 3-1 that the Big Six studios are all part of large public entertainment conglomerates and as such, are expected to pull their weight in the battle to create shareholder value—in other words, to make money.

Film divisions are important to conglomerates because they create lucrative assets. Each new release is added to a film library, which enhances the value of a conglomerate’s cable and television channels. But risk is hiding around every corner, and today’s studio executives—a very risk-averse crowd—use many strategies to fund those blockbusters and alleviate potential bombs.

A Bit of Background

Toward the end of the last century, the explosive introduction of home video provided a new stream of revenue that grew so rapidly that all the studios were making money. Awash in profits, studios paid little attention to high expenses. Talent agents, who held the keys to the stars, and directors, who drove the audiences to the theaters, worked huge deals for their clients, resulting in lavishly paid talent—and a number of famous flops. Director Michael Cimino, hot off The Deer Hunter, crashed and burned with the never-to-be-forgotten Heaven’s Gate. Waterworld, starring Kevin Costner, is still used as a punch line. (It didn’t help that Costner followed Waterworld up with The Postman, another mega-flop.)

But even without grossly paid talent, big movies are always at risk of becoming big disasters. There are a raft of other potential pitfalls—location shooting, the addition of increasingly complex special effects and computer-generated imagery (CGI)—that adds to the bottom line and therefore the risk. Disney’s Mars Needs Moms (2011; total cost $175 million against a worldwide gross of $39 million) and Warner Bros. The Green Lantern (2011; total cost of $325 million, worldwide gross $220 million) are more recent examples of box-office busts.

Wall Street analysts are unforgiving when movie divisions have a string of box office flops. With the boom of home video a thing of the past, executives are pressured to take a closer look at the bottom line. One way to corral costs is to cut back on the number of films produced, but with fewer films in production, studios do not enjoy the benefit of cross-collateralized income, a phenomenon that occurs when a studio has a broad portfolio of films, allowing losses from one film to be offset by gains from another.

So before a movie gets made, studio executives must look for ways to reduce the uncertainty that accompanies the business.

Reducing Risk: High Concept Films

Studios take great care in considering what movies will get the “green light”—the go-ahead to start production. Many of these movies are specifically created under a formulaic model known as high concept. With high concept movies, studio strategists plug in a potential genre/storyline and add a projected cast, while considering what other ways the movie can be exploited. If the modeling spits out a large enough revenue projection, the project will be pursued.

High concept movies exhibit the following characteristics:

![]() Known stars and/or director

Known stars and/or director

![]() Always a mass-market movie

Always a mass-market movie

![]() A storyline that can be rendered in a clear, simple sentence

A storyline that can be rendered in a clear, simple sentence

![]() A recurring single-image marketing motif

A recurring single-image marketing motif

![]() A connection to prequels, existing theatre, or established music

A connection to prequels, existing theatre, or established music

![]() Extensive merchandising of licensed products

Extensive merchandising of licensed products

Films with big names attached to them are still more “bankable” (some things never change), or appealing to larger audiences with more discretionary income. Big paydays still exist for evergreen names, such as Julia Roberts and Steven Spielberg, as well as those in the current crop of must-sees—George Clooney, Angelina Jolie, and a whole cast of twinkling new lights.

Dum-Dum....Dum-Dum...

The first breakthrough high concept blockbuster and the roadmap for dozens of hits since was the 1975 movie Jaws. The storyline came from a successful number-one bestseller novel by Peter Benchley. Universal added then-hot stars Richard Dreyfus and Roy Scheider and a young director with four television movies and one box office so-so, The Sugarland Express, but a lot of perceived talent: Steven Spielberg.

The marketing mavens created a campaign that still sticks in movie-goer minds. The single image used extensively in the highly-saturated print, trailers, TV commercials, and other media ads was an apparently naked woman lazily swimming across open water, with a gigantic, open-mouthed Great White Shark shooting straight toward her from below, providing a clear and arresting image of good and evil. Even children not born until 20 years later understand the tension behind the famous musical syllables that underscored the movie, dum-dum, dum-dum (a classic once again put in the limelight at the 2013 Academy Awards, to warn winners their thank-you time was almost up).

No wonder that Jaws 2 also rang the box-office cash registers.

Extending the movie brand, Universal featured that famous white shark at its theme parks, drawing shrieks from visitors until 2012, a 22-year ride for the attraction in Florida. It is still a centerpiece at Universal Osaka (Japan).

Jaws set a standard for high concept movie characteristics still followed today. A high concept movie

![]() Takes any genre or idea and uses every extreme opportunity to push its point and image.

Takes any genre or idea and uses every extreme opportunity to push its point and image.

![]() Makes absolutely sure it relates to as many diverse and broad-based audiences as possible.

Makes absolutely sure it relates to as many diverse and broad-based audiences as possible.

![]() Is packed with activity—not always just action, but rapid movement, with high focus on the current hot actor.

Is packed with activity—not always just action, but rapid movement, with high focus on the current hot actor.

This highly stimulating experience is meant to motivate repeat visits to the theater by mass audiences. When it works, those happy movie-goers continue the cycle, providing excellent word of mouth (or word of tweet, email, or Facebook post), culminating in great buzz.

The successful high concept movie may not always be a blockbuster. It does not have to cost over $100 million or have marketing budgets over $30 million. But it provides a desire for repeat viewing, generating ongoing revenue in digital downloads or cable because it hits some emotional note or empathic button.

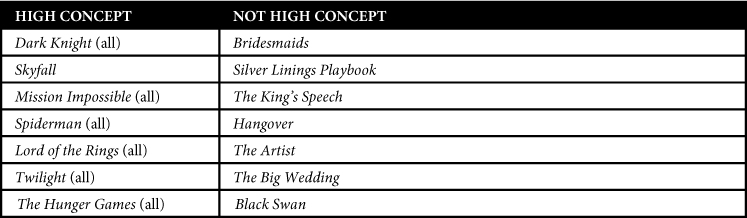

Samples of high concept versus not high concept films are found in Exhibit 3-2.

Marketing is a specific focus—indeed, central to the whole strategy—in high-concept films, right from the start.

Another offering central to studio strategy is the tent-pole film. This term is applied to a specific film that the studio has decided will be its lead picture for a given year or season.

A studio will place its production and marketing budget bets on its tent-pole film, riding it as long and as far as possible. The expectation is that the tent-pole film will generate huge box office returns and multiple supplementary revenue streams, becoming an “evergreen” product, earning licensing fees around the world, and returning for play several times over a decade.

As executives are plotting their strategies with high concept and tent-pole films, they are finding ways to finance the film through creative cofinancing deals. Here again, marketing enters the picture—this time bolstering the bottom line—in the form of product placement.

Reducing Risk: Hollywood Meets Madison Avenue

Product placement is a strategy that allows studios to gain revenue from the appearance of a specific product in a movie.

There is no simple way to calculate how many marketing messages consumers are exposed to daily. Numbers range from the low 200s (for specific commercials/print ads/radio messages) to the 1000s (for impressions made from the sheer glut of ads plastered on as many available flat surfaces—static or projected—as possible). But what we do know is, those 1,285 billion movie viewers are sitting in their seats for two hours at a time, creating huge opportunities to parade a product in front of them, little mini-commercials that associate the brand with the movie, the star, and the concept: adventure, danger, romance.

This connection has been in the movies forever (think what Humphrey Bogart did for trench coats), but savvy marketing executives realized there was a goldmine in placement. Today, it’s a given that part of a film’s financing will come through the sale of space on the screen. Film placement was estimated to reach $1.53 billion in 2011,9 no small hedge against the huge cost of producing a movie. And when you consider the cross-marketing that occurs when the product (say, a Rolex) places the star and the watch on its own billboard, the symbiosis is perfect—and very cost-effective: millions more impressions reminding the potential audience to see the movie.

9 “Global Product Placement Spending Up 10% to $7.4 Billion in 2011,” PQ Media, December 4, 2012, http://www.pqmedia.com/about-press-201212.html

One of the most successful franchises in film history, the James Bond movies, is the acknowledged master of product placement, garnering hundreds of millions of dollars over the life of the franchise. 1997’s Tomorrow Never Dies featured a full 22 minutes of product appearances, including BMW and Omega (a slap in the face to Bond purists, who expected Aston Martin and Rolex).10 Skyfall in 2012—the twenty-third Bond film—garnered an estimated $50 million in product placement, against a $150 million budget.

10 Handbook of Product Placement in the Mass Media: New Strategies in Marketing Theory, Practice, Trends, and Ethics, Mary-Lou Galician, EdD, Haworth Press, 2004.

Brand masters love the association with movies. Consider Apple, the creator of Macs, iPads, and iPhones. Apple has carefully nurtured its hip image over the years with those wonderfully creative ads, but they’ve also relied on the movies. Apple products appeared in 42.5% of the 40 number-one U.S. box office films in 2010. Apple-branded products appeared in more than one-third of all number-one films at the U.S. box office between 2001 to 2010,11 and continued the practice into 2012, when they went public with their strategy in testimony related to a patent infringement suit with Samsung.

11 Brandcameo.com, Announcing the Brandcameo Product Placement Award Winners, www.brandchannel.com/features_effect.asp?pf_id=521, February 22, 2011.

It’s certainly difficult to compute the exact impact to Apple’s bottom line, but there’s no doubt it’s putting its product in front of millions, if not billions, of potential buyers, in a medium that will continue to deliver impressions as those movies make their way through all the platforms available to them in windowing.

The catch with Apple? It claims to have never paid for placement, but it does furnish product—and a particularly hip cachet.

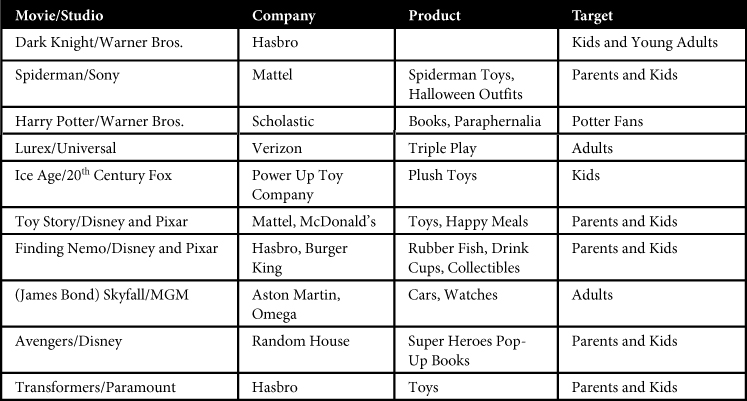

Another revenue strategy for movies comes in the form of product tie-ins. We take a closer look at specifics a little later in the chapter when we talk about the actual marketing of the movie, but for now, keep in mind that all those dollars generated through McDonald’s Happy Meals and Omega watches fall right to the bottom line.

As an entertainment marketer, your job is to find every possible way to leverage and exploit your movie, through every single window it passes through. Product placement and tie-ins are just the beginning. These two strategies allow studios to reduce risk by bringing in outside funding for those ever-more-costly movies.

But it isn’t just live action that packs the profits into the studio coffers (hopefully). Another type of feature that has gained presence is animation.

Another Profit Powerhouse: Animation

Animated films allow for huge merchandising and licensing deals, stretching the brand across the globe, while generating additional marketing support for the original product.

For most of the twentieth century, animation meant Disney. After all, Walt Disney founded his studio with Mickey Mouse and became known as the king of family fare with the vast stable of characters that followed Mickey. Even as he pushed forward with live-action film classics like Old Yeller and television staples such as Zorro and Davy Crockett, when you said “Disney,” you thought “Mickey.”

What Disney realized, very early on, was this: You don’t make animated features for children. You make them for parents. Children do not drive themselves to the theater or pay for their tickets. If you add enough adult-level interest, humor, and morality to an animated feature, parents will gladly take their kids.

The multi-billion dollar empire that is now Disney, stretching from theme parks to cruise ships to live-action and, yes, animated films, owes everything to that squeaky-voiced mouse—oh, and Walt, Michael Eisner, and now Bob Iger. These three men, along with Jeffrey Katzenberg (who brought animation back to the forefront with The Lion King—the first billion-dollar animated feature, cross-platforming all the way to Broadway), created a powerhouse that seems almost a part of our DNA.

The reason for that deep, entrenched loyalty has as much to do with warm and fuzzy fare as it does with brilliant brand extension and licensing. The intellectual property owned by Disney seemingly stretches everywhere in the world, including English-as-a-second-language schools in China, featuring the characters—a brilliant move that will serve the brand well, as this enormous potential market comes to fruition.

And due to superb management of the brand, Disney’s intellectual property is held for rerelease on a carefully timed schedule. Interested in owning Fantasia? Available for years, on Blue-Ray or DVD. Cinderella? Not rereleased until 2012. You can bet that the Disney coffers filled once again and not just from the animated feature. There was plenty of licensed merchandise to accompany it, once again supporting the phenomenal brand that is Disney.

Not that Disney has rested on those animation laurels, by the way. Disney’s deal with Pixar, the early masters of computer-generated imagery (CGI)—creating such mega-successes as Toy Story, Monsters, Inc., and Finding Nemo, eventually built some bad blood between Disney and Pixar, given the inequity of a split heavily weighted in Disney’s favor. The solution? In 2006, Disney purchased Pixar, and the beat went on, leading to Ratatouille, Up, WALL-E, Brave and Cars.

But moving into the new century, other studios also realized the power of animation, extending and supporting their own brands through licensing and merchandising such well-known non-Disney franchises as Ice Age (1 through 4) from Blue Sky via 20th Century Fox; Despicable Me from Universal’s Illumination; and Shrek (1 through 4) from DreamWorks. DreamWorks, of course, was the brainchild of Steven Spielberg, David Geffen, and Jeffrey Katzenberg (Mr. Lion King), who left Disney after the power plays left him out of the president’s chair.

The ratcheting level of competition between all these studios creates the need for powerful marketing programs to gain attention and a share of parents’ pocketbooks.

As a side note, the impact of CGI needs to be mentioned. Not limited to pure animation releases, CGI has become a staple of the film industry. CGI, also called computer animation, is essentially the next step on the ladder from classic frame-by-frame 2D illustrations (all original animated Disney features) and stop-motion 3D (think Frankenweenie). CGI has created the magic of Avatar, switching from live-action to fantasy, and the classic battle scenes of Lord of the Rings (not to mention Gollum).

Animation has grown as a genre not just because of its popularity with children and holiday-hassled parents. The genre has some major advantages for studios:

![]() Animated characters get no salary, residuals, or benefits.

Animated characters get no salary, residuals, or benefits.

![]() The characters are brands unto themselves and can be marketed through licensing toys, merchandise, and must-haves.

The characters are brands unto themselves and can be marketed through licensing toys, merchandise, and must-haves.

![]() Animation can be created by software, which is faster and cheaper than traditional frame-by-frame hand-drawn animation cels.

Animation can be created by software, which is faster and cheaper than traditional frame-by-frame hand-drawn animation cels.

![]() Kids’ word-of-mouth is strong, gaining the attention of their friends and their parents.

Kids’ word-of-mouth is strong, gaining the attention of their friends and their parents.

![]() Seasonal marketing is easier; animation peaks during holidays from school.

Seasonal marketing is easier; animation peaks during holidays from school.

![]() Voices and animation are usually recognizable stars, but the features are not reliant on that star power.

Voices and animation are usually recognizable stars, but the features are not reliant on that star power.

![]() Animation is easy to market via TV and trailers.

Animation is easy to market via TV and trailers.

![]() Most animation has a morality story—good versus evil—offering positive imagery for marketing to parents.

Most animation has a morality story—good versus evil—offering positive imagery for marketing to parents.

![]() The strongest of the animation brands are walking billboards on lunch boxes, backpacks, T-shirts, jackets, and every possible product you can mention. This creates both additional revenue streams and additional marketing support for the original product. Additional tie-ins—creating the same effect—include fast food (McDonald’s, Burger King), beverages (Coke and Pepsi), cold cereals, and vitamins.

The strongest of the animation brands are walking billboards on lunch boxes, backpacks, T-shirts, jackets, and every possible product you can mention. This creates both additional revenue streams and additional marketing support for the original product. Additional tie-ins—creating the same effect—include fast food (McDonald’s, Burger King), beverages (Coke and Pepsi), cold cereals, and vitamins.

![]() Animation, in home video, has high sales and rentals and supports repeat viewing (often acting as a babysitter).

Animation, in home video, has high sales and rentals and supports repeat viewing (often acting as a babysitter).

However, even with experts conjuring up complicated models and “can’t miss” formulas, accurately predicting movie performance is virtually impossible. There is no machine, computer, abacus, or psychic connection that can create the concept, script, and direction to turn an idea into a blockbuster financial success or critical artistic achievement.

The industry’s past, present, and future depend on writers, directors, actors, cinematographers, and all the other behind-the-scenes professionals—not the least of which are the individuals involved in marketing.

Behind the Scenes: The Producer

The marketing of a studio’s film is generally presided over by the president of marketing and his or her staff. However, many phases of marketing individual films are handled by the producer.

There are two types of producers that are used by the major movie studios, and the responsibilities are different for each.

Every large studio has in-house producers. An in-house producer, on a “work for hire” arrangement as a salaried staff member, has restricted responsibilities primarily focused on controlling the budget, scheduling, and coordinating on-location staff with studio executives. Problems of any magnitude are usually discussed with the studio chiefs. The promotion of a film is overseen by the president of marketing.

However, studios might also work with independent producers. (Note that an independent producer is not necessarily working on an independent film, which we discuss later. In this discussion, an independent producer is working on a studio project, taking the place of the in-house producer.)

Independent producers are used for certain unique properties being developed by the studio. But an independent producer may also bring an idea to a studio—for example, Jerry Bruckheimer, who has his own production company—with many producers on staff—brought Pirates of the Caribbean to Disney.

In this case, the producer can option a property, book, or screenplay with personal funds and then hire the writers, director, star, and extras or work with a talent agency to package the talent for the film. It is frequently up to the independent producer to develop the treatment or write the script to build up both momentum and credibility for the product. The independent producer is usually also responsible for the functioning of the film: the complete agreements for distribution, casting, collaborating, and managing the process.

Little of this work is performed by the executive producer, who usually gets this title because of a majority or significant financial investment in the production of the film. Sometimes a star obtains the title of executive producer, either for his or her bankable nature or need for ego-stroking.

Ignoring the independent producer’s role as a marketer would be tantamount to describing the cinematographer’s role as merely that of a cameraman or the head of distribution at a studio as a sales clerk.

An independent producer must be a marketing generalist, working with advertising professionals when the budget for marketing exceeds $10 million. Even then, the independent producer is involved with all aspects of marketing, including strategy development, trailer composition, selection of key visuals for print and poster advertising, Internet and social networking applications, and negotiating agreements with the stars to do publicity stills.

The independent producer also works with the advertising agency or media buying service to ensure that the message is correct and that the media is effectively purchased and targeted at the predetermined audience. He or she also coordinates any licensing and merchandise contracts with the licensees, seeking an integrated communications image—an important goal, if the licensees are obligated by contract to spend advertising budgets in support of a new toy, publishing or music product, or other licensed item.

Regardless of whether the producer is independent or in-house, be assured that no one is surprised to see the involvement of the president, the CEO, and perhaps even the chairman of the studio when the initial production budget is $100 million or above and the marketing investment is $25 to $30 million.

When films spiral over budget—as they often do—there is a frequent need for top management to expand their share of voice against the competitive film offerings. When there is a summer of blockbusters, with five or more films at the $100 million level, management and the creative staff are in frequent discussion, working to ensure that the studio’s product will measure up to the competition. When those films are all competing for the same audience, shifts in scheduling frequently occur at the last minute to create better windows of opportunity for the movie’s opening weekend.

This movement is happening more often now, as production heads realize that movie openings are all about logistics.

All of this discussion can turn to major conflict when things begin to go wrong. Yet in the highly volatile, content-driven and risk-averse business of movie-making, the “suits” are often loathe to stop the creative process for fear that something magical will occur. Thus, there was no way to stop Heaven’s Gate or Titanic once they were in full production.

Heaven’s Gate grossly exceeded its budget and was a historic flop, setting a precedent for out-of-control production. The cost of Titanic was nearly double the initial projected budget but had a theatrical box office of over $1.5 billion and became such an evergreen product that it was rereleased in 3D format 15 years later, jumping over $200 million in only 12 days.

Out the Door and Onto the Streets: Distribution

Getting the film from the studio to the screen takes a big chunk of the marketing budget. This process is known as distribution. In the past, when movies were actually distributed as film in large canisters that went to the theaters for screening, costs to distribute could vary based on the initial number of screens (how “wide” it opened) and whether or not the film had “legs” (a long, successful run at the theaters, with many more screens added after opening weekend).

At $2,000 a pop, with a typical opening of 2,000 screens, the cost of prints added up. Add to that the initial advertising budget and a $100 million movie quickly added anywhere from $25 million to $50 million to the cost. With a successful box office run, that number no longer had any anchor holding it to the ground.

For a variety of reasons, not every studio handles its own distribution. Many studios cut deals to have other studios distribute their movies. And the studios are happy to have them. The industry metric for a distributor’s compensation is one-third of a film’s box office. In other words, potentially more profit for those major studio distributors without taking the risk of making the movie.12

12 There are select independent distributors who may consider lower rates for particular movies. Bob Burney cut a deal with Mel Gibson to distribute The Passion of Christ for only 10%. However, Burney was willing to take a risk on a larger return, a bet that paid off. He took his 10% off a $400 million box office.

Animated feature distribution is an especially nice niche for those studios without animated divisions of their own. Fox recently signed a distribution deal for DreamWorks—which created the multiple versions of Shrek, Madagascar, Kung Fu Panda, and How to Train Your Dragon—whose distribution had been previously handled by Paramount.

At the time of this writing, there are many in the industry wondering if Mr. Katzenberg might be bringing his magic to yet another animation division, a Fox combo of Blue Sky and DreamWorks. But the stated reason for DreamWorks’s shift to Fox is the obvious cross-platforming with Fox’s FX cable network, as well as that studio’s concentration on digital distribution.

Digital Distribution

The advent of digital transmission allows the studios to reduce the costly process of producing and distributing prints. Not all screens have converted to digital, so some prints must still go out. As of 2012, the breakdown was as follows: regular analog screens, 6,423; digital and 3D, 14,734; digital and non-3D, 21,643; total screens, 42,803.13 That’s a 50% decline in analog screens in one year.

13 Motion Picture Association of America (Rentrak 2012 research).

Digital transmission is clearly the wave of the future, with benefits for both the studios and the exhibitors. It is less costly for the studios, but having access to digital transmission opens the doors for exhibitors to expand their offerings—and their revenue—filling seats for live screenings of everything from boxing to opera.

Studios are now much more nimble, with the advent of digital technology, expanding their reach not just domestically but internationally. The increase in digital transmission created a big boost for international box offices in 2012, when the major international markets grew 35% over 2011.14 The international box office adds a hefty amount to a movie’s take. The year 2012 saw the international box office hit $23.9 billion compared to $10.8 billion in the U.S.15

14 Motion Picture Association of America (Rentrak 2012 research).

15 Motion Picture Association of America (Rentrak 2012 research).

Piracy

One of the most critical factors in digital transmission is the ability to get movies to screens immediately, everywhere. Piracy—the out-and-out stealing of copyrighted content for illegal resale—flourishes if the audience, whether in New York or New Delhi, cannot quickly and easily see the film.

This technological wonder doesn’t end the threat of piracy; in fact, in some ways it can make it easier. The Motion Picture Association of America said that the movie industry loses billions of dollars every year to Internet piracy. The phenomenon is widespread in part because of file-sharing technology such as that utilized by BitTorrent.com, which allows computer users to copy large files—like movies—and share them.

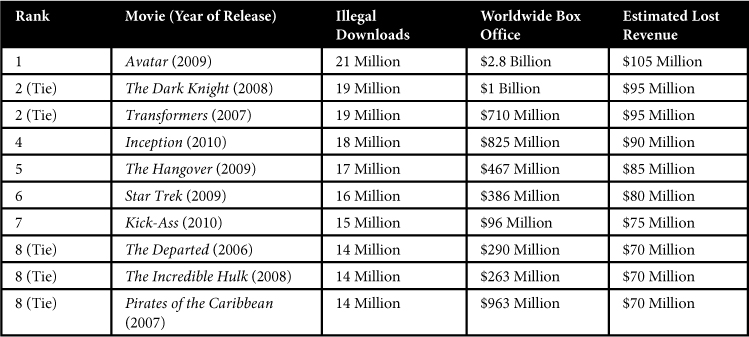

Sides have been drawn on this issue, with the movie industry justifiably on the “con” side. Techies who appreciate the value of file sharing take an alternate view. In any case, we do have the ability to track the impact. TorrentFreak.com, which monitors and stores the data reported by different BitTorrent trackers, released this list, shown in Exhibit 3-3, of the ten most-pirated movies of all time, compiled from BitTorrent files since 2006.16

16 CNBC.com, The 10 Most Pirated Movies of All Time, www.cnbc.com/id/48768803/10_MostPirated_Movies_of_All_Time.

Piracy is a phenomenon that attacks international box office revenue. That box office is growing every day. There are 300 million people in the United States and 7 billion people in the world with somewhere between 3 and 4 billion people who are considered middle income in their own environment. With the ever-increasing entertainment appetite of rapidly evolving countries such as China and India, global entertainment—and global entertainment marketing—is a huge market rapidly rising on the horizon.

Down the line in the life of a movie, broadband and wireless, hand-in-hand with all the new hardware these conduits feed—smartphones, TVs, laptops, tablets, airplane screens—have created huge new outlets of distribution. Now that digital information can be compressed and streamed, the consumer is king, choosing when to see the movie, on whatever size screen he wishes, at whatever hour of the day or night that is convenient to him. The number of distribution outlets that provide the full movie without any interruptions has climbed enormously. And the process of acquiring that movie has gone from a three-hour drag to a lighting quick download.

Theaters: Still Big Box Office

In a time when consumers have greater and faster access to movies than ever before—with home-theater systems to rival the sound and image quality found in small movie houses—it would seem as though marketers would face an uphill battle to lure audiences into the theater to view any one of the over-600 films17 released each year.

17 Motion Picture Association of America (Rentrak 2012 research).

And when you add the ever-increasing price of going to the movies—with almost $20 per ticket in major metropolitan areas, another $20 for popcorn and soda, one fistful of bucks for the parking lot attendant and another for the babysitter—you might think that the theaters would be pretty empty.

But here’s the news: the U.S./Canada box office grew 6% from 2011 to 2012, with 225 million persons going to the movies at least once in 2012.18

18 Motion Picture Association of America (Rentrak 2012 research).

Even though the domestic box office (DBO) only accounts for a percentage of total film revenue, it is the scorecard, the buzz-creator and sustainer that drives all other revenue that will be generated by a film, from downloads to licensed products. It is that ancillary business that often provides a major portion of a film’s profits.

So with all the access to movies on other platforms and with a rising cost of a movie ticket, why are people still going to theaters, still creating that DBO? People are social by nature. Although social networking platforms provide a place to connect thought instantaneously, people of all ages still follow their instinct to herd. And young people, in the throes of mating, know that there is only so much that can happen when sitting home alone in front of a screen.

Entertainment is one of the primary opportunities to accomplish a connection with others, and in our present-day culture, movies still offer the chance to sit in the dark with 300 strangers (or your date) and participate in laughing, crying, thinking—and touching—and generally being swept away by the entire experience.

This fact is not lost on exhibitors. AMC Loews, Regal Cinemas, General Cinema, Carmike, Mann Theaters, and others are focusing on the quality of the in-theater experience in an effort to shift movie-going from a commodity, competing with all the other viewing opportunities, gearing up for this battle by building newer, bigger, better, cleaner, multiscreen mega-plexes, most of them with best-quality surround sound and state-of-the-art image projection, including 3D.

Exhibitors are also utilizing online ticket purchasing, stadium seating, snap-in food trays, credit card kiosks, fancy coffee bars, high-priced but filling comfort food, bright clean bathrooms, larger inside waiting areas, and placement near other amusement areas for after-movie interests. In major market areas, movie-goers can reserve seats, just as they might at a live theater venue.

This is all part of the arsenal of the leading theater chains and has contributed to another phenomenon: consumer’s inelasticity to ticket price increases. Even with some metropolitan areas reaching the $20 per ticket level, there has been relatively little reaction from the public.

All of this funnels back into the all-important opening weekend and the marketing that must be done to get the audience in the seats. In the short lifespan of a film’s initial release, the most critical time period is that opening weekend because it accounts for 20% of total box office gross.

Therefore, marketers have an awfully short window of opportunity to create a brand image for movies—the image that will pave the way for the windfalls beyond.

Movie Marketing: Who Are the Targets?

Today’s blockbusters, including the Iron Man, Bourne, and Harry Potter franchises, have all expertly used time-tested, high concept techniques to create huge box-office returns. Aimed at not only building excitement but also maintaining it, marketing campaigns use all forms of traditional media—print, cable and network television, radio, and billboards.

With the more recent addition of the Internet and all that it offers—social networking, dedicated websites, links to other websites, twitter feeds, and all forms of constant contact—studios now have multiple ways to quickly build huge interest in films.

And who’s interested? One of the key market segments that still sweep into the theater are teens and young adults—a heavy movie-going group. Twelve-to twenty-four year-olds are the most frequent movie-goers, with an equal male/female split. Hispanics also enjoy movies more frequently. These two groups buy half of all tickets.19

19 Motion Picture Association of America (Rentrak 2011 research).

Teenagers will always search for the one private place to congregate away from the eyes of parents, teachers, and other adults. Although online social networking sites allow for conversation, movie theaters allow for touch. Even as screen-time has more to do with computers and smartphones, 12–18 and 20–25-year-olds still head to movies in droves. This has made the teen and young adult demographic the most sought after by movie studios and their marketing partners. Whether or not they can be weaned from texting and tweeting while in the theater remains to be seen.

The presence of this tempting, free-spending demographic has had a dramatic impact on movie content, as studios churn out what seems to be an endless string of action and special effect-driven films that might or might not actually contain meaningful content.

But a new challenge has arisen in this important demographic: the rise of electronic gaming, especially among males ages 18 to 35. We cover this platform later, but in terms of movies, games have created a separate path in the entertainment experience.

The defining characteristic of gaming is the ability of the participants to actually change the story line based on their own moves and strategies. And as the technology of games has improved to the point of delivering high-quality imagery and sound, it has begun to challenge the in-theater movie experience for this age group. Studios are responding with action-driven movies that feature even more graphic images of mayhem, sometimes featuring a Web-based game as an appetizer in an effort to bring gamers to the theater.

However, one true-blue demographic has caught the eye of studios: Baby Boomers. Raised on the movie theater experience, Boomers have become a hot demographic for studios as some segments have begun to look elsewhere. Big releases in the first decade of the new century included The Expendables (one and two), RED, Julie & Julia, The Exotic Marigold Hotel, Gran Torino, and True Grit, featuring stars well into their 60s, 70s, and 80s. Names such as Morgan Freeman, Jack Nicholson, Meryl Streep, Helen Mirren, Tommy Lee Jones, and Arnold Schwarzenegger still attract the Boomer demographic, a group with tons of disposable income and discretionary time.20

20 “Old People, Old Stars: Hollywood’s New Hot Demo Is Saving the Box Office,” The Hollywood Reporter, August 22, 2012.

Studios have also begun to offer a far different image to young girls and young women than the old princess-who-must-be-saved model, finally recognizing that girls are movie-goers (possibly even more loyal than the previously mentioned game-playing boys). Though there’s still plenty of pretty pink, movies such as 2012’s Snow White and the Huntsman—where the heroine does not break up her coronation by rushing down the aisle toward her true love, choosing instead an equal affirmation and a steely look across her subjects—heralds a new concentration on a demographic with spending power and word of mouth.

Finally, we have a phenomenon known as crossover. Although crossover is typically used in the music industry (covered in a later chapter), the concept has emerged as the standard for celebrities who extend their careers across movies, music, television, and Broadway. The marketing machine ramps up when Will Ferrell, who got his start in improvisational comedy (The Groundlings) and went on to television (Saturday Night Live), leaps from the small screen to the big screen (Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, Elf, Blades of Glory, The Campaign) to Broadway (You’re Welcome America. A Final Night with George W. Bush)—or when Grammy-winning Joss Stone takes a turn in Showtime’s The Tudors.

This is brand extension, pure and simple. But that extension has a direct payback to the movies, for crossover works both ways, luring audiences from one medium to another after they’ve been introduced to the star.

Even more important to the crossover discussion is the ever-emerging mix between cultures and countries, with stars from particular niches (Jennifer Lopez, getting her start singing in Spanish in Selena, or Dev Patel opening the big doors with India-based Slum Dog Millionaire) finding huge success across language and media platforms. What’s particularly interesting about these two examples? Although entertainment audiences see both these stars as specific to an ethnic background, Lopez was born in the Bronx, and Patel is British, born in Harrow. But they both bring new, emerging audiences to the theater.

Make no mistake: Today’s entertainment marketing executive had better have a crystal clear view of the global market. Despite whatever challenges there might be between countries politically, entertainment in all its forms rings cash registers around the world.

We touch on global entertainment in a later chapter, but now let’s concentrate on the how-tos of filling seats.

Movie Marketing: Creating Wannasee

We have the film, and we have the audience. Now we need to bring them together.

The movie marketer’s challenge is to create “wannasee” among consumers, creating enough buzz or word of mouth to drive viewers into the theater, resulting in the classic marketing outcome of turning want into need.

As mentioned earlier, marketers have an extremely short window of opportunity, with increasingly high competition. Remember: Movies aren’t just competing against other movies; they are competing against every other form of entertainment out there (not to mention doing nothing). To create strategies that will drive audiences into theaters, movie marketers—like consumer product marketers—rely heavily on consumer research. Focus groups, surveys, and in-depth interviews help studio executives make critical marketing and production decisions. Among those decisions are the following:

![]() Is the target audience correct?

Is the target audience correct?

![]() Is the trailer compelling, creating “must see?”

Is the trailer compelling, creating “must see?”

![]() Is the marketing believable?

Is the marketing believable?

![]() Is the audience laughing at the right spots?

Is the audience laughing at the right spots?

Like every other supplier in this age of risk reduction, studio executives want to have a guarantee that their films will appeal to wide audiences. Though there is no such thing as guaranteed success, consumer research can help ease the angst. But there has been more than one studio executive who tossed the research out the window, going on his or her gut instinct, and lived to tell the tale.

Being too cautious has its own risks. One famous example of this was the launch of the first Toy Story movie by Disney. This coproduction with Pixar was expected to be a more minor release but quickly blew up into a box-office phenomenon. Disney reportedly missed out on an estimated $200 million in licensing and merchandising revenue because insufficient licensed product had been prepared for the Christmas rush. It was an expensive lesson but one that wasn’t forgotten for Toy Story 2, 3, and whatever other number has yet to be introduced.

Marketing Methods

Regardless of the strategy or instinct, there are a variety of methods utilized in the marketing of a film. Some are actual processes; others are more conceptual in nature. The following are typical promotional strategies used in the marketing of movies.

Test Screenings

During the production and editing of a film, it is crucial to get a reaction from the target audience. Studios get this feedback via test screenings. Typically, passes will be randomly distributed in front of a movie theater. The pass entitles the respondent to see an unfinished version of a film. After the film, the audience is asked to fill out a lengthy survey, asking detailed questions about the characters, plot, and scenes. The audience reaction is reviewed, and appropriate changes may be made.

Although test screenings are a useful marketing tool, the growth of the Internet has created new risks. Information that leaks from tests can result in disaster. The studios got a nasty introduction to viral backfiring years ago when Warner Bros. had a test screening on a version of the big-budget Wild Wild West that had not been completely edited. The test went so poorly the audience actually booed.21 Even though the audience signed confidentiality agreements, the news quickly spread via the Internet, where anonymity makes it easy to dish bad buzz. This proved disastrous. Warner Bros. was unable to control the negative buzz, and the movie was a box office failure.

21 Svetkey, Benjamin, “Even Cowboys Get The Blues,” Entertainment Weekly, July 8, 1999.

Sneak Previews

Sneak previews can build buzz, but studios prefer to set them up if they are confident the preview audience will provide favorable word of mouth prior to opening. It is not unusual for studios to avoid sneaks if they know the film will generate bad buzz. In this case, studios will open the “flop” as wide as possible without any sneak previews. If the advertising campaign is successful, a significant audience will show up opening weekend to see the film, helping to cover some of the costs. But inevitably, the negative word of mouth will circulate, and the movie will be out of the theaters in less than the usual four-week window.

Movie Trailers

When the marketing juggernaut begins to move, movie trailers are must-haves. Although media and print are important to a movie marketing campaign, the movie trailer is the most crucial element. The best trailer is a tiny movie unto itself, telling a story and whetting the audience’s appetite. The studio executive’s challenge is to get people to see a film without telling everything about the film, and a successful trailer does just this.

Typically, two trailers are produced. The first is called the teaser trailer, which is shown in theaters six months before the film is released.22 The second trailer tells more of a story and is shown in theaters ten to eight weeks before the film opens. With today’s access to the Internet, additional trailers may also be produced. More about that in a minute.

22 Lukk, Tiiu, Movie Marketing, Beverly Hills, CA: Silman-James Press, 1997.

Trailers have their plusses and minuses, depending on the movie as a whole and what’s left on the cutting room floor. If handled by an expert, with the guidance of a movie marketing professional, trailers can hit a home run with the target audience. However, many studios allow the filmmakers to play a role in the marketing of a film, which can often lead to clashes. Marketers are trying to deliver what the consumer wants, while filmmakers can be concerned with the integrity of the story. The two don’t always match.

The marketer isn’t always in the right, though; too much creative license can be disastrous. To capture the attention of the appropriate segment of the audience, a trailer might focus on a certain element of a film, making the movie appear to be more of a solid representation of a genre than is truly deserved. The only slightly sensual, barely action-oriented, or vaguely funny comedy may utilize a trailer that exaggerates any of these elements. Consumers who have no other source of information can be disappointed when they actually see the movie, and thus negative word of mouth is created.

Then there’s the question of giving away too much. A survey taken in April of 2013 by YouGov.com found that 49% of Americans feel that movie trailers give away too many of a film’s best scenes. 32% felt that trailers gave away too much plot, while 48% disagreed. Would that stop audiences from seeing a film? 19% of respondents said that too-revealing trailers have deterred them from seeing a film, but 24% said it makes them want to see the film more. 35% said it has no impact at all.

In other words: it’s pretty much a draw. Given the increasing attendance in movie theaters, it would appear that there’s a fairly good balance in what trailers represent. However, the group that feels some trailers show all the best scenes may have a point. More than a few marginal movies make it to the theaters, and in those cases, those few best scenes are the only thing the film has going for it.

That same survey found that trailers play a huge role in getting people into theaters: Americans cite the two biggest factors in helping them decide which movies to see as trailers (48%) and personal recommendations (46%).

Trailers can also garner two different audiences for a movie that has a distinct but potentially dual personality. The Adjustment Bureau, a 2011 film starring Matt Damon and Emily Blunt, functioned both as a thriller and a romance. With the Internet offering a conduit for multiple versions of the trailer, potential audiences were able to make a decision regarding the film based on their own desired point of view. The trailers were accurate in their use of footage from the film but simply focused on the action and drama for the male audience and made the romantic scenes more prominent and expansive for the female audience. Neither audience was disappointed because both were satisfied by the story, content, and elements each was seeking. Women brought men, and men brought women, resulting in a great marketing success.

Trailer Distribution

Trailers can run a few minutes when shown in a theater, can be cut to a 30- or 60-second version for TV commercials, or can run as long as five to six minutes when placed as part of a rolling series of previews or display on social networking sites. In the past, trailers were seen in only a few places—the theater, a television commercial, at the beginning of DVDs, or a download from Netflix. But with the advent of the Internet, the marketing potential of trailers has exploded.

No longer confined to the movie theater or a television commercial spot, trailers are now available all over the Internet—Facebook, YouTube, the movie’s website, associated websites, Fandango, Moviefone, IMDb.com, any link from any media source. Viewers can play them again and again (a marketer’s dream!) and enjoy several different versions. The consumer is now in full control of how and when she or he wants to consume that little bit of movie.

The cost-effectiveness of the Internet is unlike anything in traditional marketing. Those who wish to view the trailer can do so as many times as they want and share it with as many friends as they like. On the happy chance that the trailer goes viral—spinning over the Internet to millions of eyeballs—the cost disappears into the ether.

Television Commercials

Even with the importance of trailers, television is where most of the media dollars are spent because unlike the Internet, the majority of television exposure must be paid for. Even with the rise of the Internet, television still has the most consistent reach for marketing movies.

No other vehicle, including cable television, can reach as many people with one trailer as broadcast television. One spot on primetime television reaches over 25 million viewers. Between networks, cable, satellite, and syndication, well over $70 billion is spent yearly in the U.S. alone.23

23 PwC Global Entertainment and Media Outlook: 2012–2016, www.pwc.com/outlook.

The goal of the commercial is to grab the audience’s attention. Whereas a trailer (in the theater) has a captive audience, a commercial has to fight to keep the viewer from changing the channel. Because of this, most movie commercials rely heavily on good reviews and sexy images from the film—the type of content proven to keep viewers’ fingers off the remote. Movie commercials are aired predominantly on Thursday evenings, when consumers are making their plans for the weekend.

Movie marketing strategies for blockbuster films—opening wide to over 2000 screens simultaneously—incorporate specific television tactics. The media plan is developed over months of planning, with backup options in place for signs of success or weak performance. The strategy includes local TV and cable to capture specific target audiences:

![]() Romantic films are advertised on Lifetime Channel, Women’s Entertainment (WETV), Food Network, Oxygen, the Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN), and any other predominantly female conduit.

Romantic films are advertised on Lifetime Channel, Women’s Entertainment (WETV), Food Network, Oxygen, the Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN), and any other predominantly female conduit.

![]() Adventure films, spy stories, murder mysteries, sports films, and violent movies are advertised on ESPN, Fox Sports, Monday Night Football, Spike, and the traditional networks, adjacent to similar shows and movies.

Adventure films, spy stories, murder mysteries, sports films, and violent movies are advertised on ESPN, Fox Sports, Monday Night Football, Spike, and the traditional networks, adjacent to similar shows and movies.

![]() The prime movie-going audiences (12–18 and 19–25) are reached on MTV, VH1, BET, and on situation comedies (sitcoms) popular with that demographic: Modern Family, Two and a Half Men, and all the clones of these shows, along with such reality television as The Voice and American Idol.

The prime movie-going audiences (12–18 and 19–25) are reached on MTV, VH1, BET, and on situation comedies (sitcoms) popular with that demographic: Modern Family, Two and a Half Men, and all the clones of these shows, along with such reality television as The Voice and American Idol.

Newspaper Advertising

The local newspaper has always been a mainstay, an underpinning for all movie advertising. The big marketing blitz for a perceived or actual blockbuster will get a double-page spread and a teaser campaign in every local newspaper city by city, as long as there are screens in that area. Almost all “A” movies (big-budget, big-star films with an expected four-week run or better) will get at least one full page in the Sunday editions.

Most newspapers have either their own film reviewers or use nationally syndicated reviewers. If their evaluation of the movie is positive, they may even find their quotes picked up as part of the film’s campaign. However, this tactic received a lot of press in the summer of 2001, when it was discovered that Sony Pictures had fabricated a reviewer, who, of course, gave great reviews to Sony films.

An important part of newspaper’s support of the film industry are special issues. The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times provide a series of special film issues each year. These can include the following: Spring Film Preview, Oscar Films, Summer Film Preview, Fall Film Preview, Holiday Film Preview, and the Hollywood Issue in The New York Times Magazine.

Variety magazine provides an extensive movie description and analysis of every new movie.

Movie Tie-Ins

Earlier in this chapter, we discussed the financial impact of tie-ins and their importance to the bottom line of the film. From a marketing perspective, movie tie-ins create great symbiosis. The brand—McDonald’s, BMW, Omega watches—gives films added exposure through their own ads and publicity, while films deliver the buzz that keeps the brand hip (or at least current). The list of products is nearly endless, as both partners strive to create “havetosee” and “havetobuy.”

The most desired demographic is the teenage market, a demographic with plenty of disposable income and a desire to connect with a particular identity as they strive to create their own.

Association with popular movies has created marketing success stories for companies as diverse as Aston Martin and McDonald’s (see Exhibit 3-4). All report increased sales during tie-in periods.

Ticket Presale Conduits

Ticket sales left the box office with the advent of Moviefone, which allowed customers to dial 777-FILM and purchase tickets in advance. After the service moved online to moviefone.com—tied in to the then industry leader, AOL—the ticket purchase process was forever changed.

AOL paid the two Moviefone developers and their original investors millions of dollars for ownership of this very valuable marketing tool. Moviefone offered direct access to customers, while providing another media platform. It generated massive advertising revenue from major studios and film distributors eager to reach various segments of the movie-going public.

Moviefone was eventually bought by The New York Times. AMC/Loews cloned their own product, available via the Internet. But the winner in this category is Fandango, which allows for advance purchase of tickets and features the all-important movie trailer. Fandango users can purchase advance tickets on both the Fandango website and the associated smartphone app. This mobile presence offers marketers a chance to build box office by catching potential moviegoers just as they make their plans for the evening.

These conduits are another example of powerful symbiotic marketing tools. Studios have yet another platform to create buzz, and exhibitors have an external box office.

The Oscars—A Powerful Marketing Tool

Everyone in the movie business knows the leverage a nomination at the annual Oscars can provide for a movie. The award ceremony itself is broadcast around the world, both live and taped for delayed broadcast, and is viewed by well over a billion people. This supports both DBO and foreign distribution.

Much has been said about the process of selecting the candidates for every award and the nature of the performance by the Master of Ceremonies, including Billy Crystal, Whoopi Goldberg, David Letterman, and Steve Martin. On Oscar night, it isn’t just the movies that get the buzz. James Franco and Anne Hathaway, both talented actors in their own right, learned the hard way that a bad night hosting the Oscars can lead to an even worse morning.

In 2013, the Academy, looking to build ratings in the 18 to 34 male demographic, brought Seth MacFarlane in as host. He brought a new low to the evening, creating more of a sophomoric roast than a toast—not what the traditional Oscars fan expected. As actress Jamie Lee Curtis later commented,24 what if the actors and actresses stopped coming to the ceremony, not enamored of being skewered by Hollywood footnotes? Building ratings has its challenges.

24 Curtis, Jamie Lee, “And the Oscar Goes to...Hell,” Huffington Post, March 1, 2013 www.huffingtonpost.com/jamie-lee-curtis/and-the-oscar-goes-to-hell_b_2793392.html.

Additional coverage, all of it acting as additional marketing for the movie, includes widely distributed reviews of the acceptance speeches (which range from maudlin, tear-filled, and boring to hysterical and occasionally heartfelt or funny) and preshows that focus on the clothes and opinions of the stars.

However, the serious players in this event understand that a win, with careful promotion and competitive tactics, can add as much as $30 million to the DBO revenue and untold millions in foreign and supplementary revenue. So-called “smaller” movies—non-blockbusters—such as The Artist, Iron Lady, and The King’s Speech, have all benefited from Oscar and his largesse.

The Oscars has become a must-see for movie fans and those who want a quick review of films they should see if they have limited viewing opportunities.

And what would the film industry be without the obsessed? Many films have enjoyed multiple visits by audiences captivated by award-winners. It is still a discussion of great wonder and envy that a portion of Titanic’s female teen audience members saw the film more than 10 times, with some memorizing dialog from the love scenes. These same fans probably made up the base for the 2012 3D relaunch as well.

Techno Tools

Today, no film is released without a website, and most have websites long before the movie is ready to be distributed. Websites built excitement, create interest, allow for multiple showings of those trailers, and due to data collection allow studios to get a feel for just how many people are connecting with the film.

A successful website is highly imaginative and engages the audience, really connecting them with the story and the characters. Often, the site will provide links to related political, financial, and historical issues and certainly to the product tie-ins discussed earlier. Seeking to actively engage the audience in an experience, many sites will feature interactive devices, such as games or contests.

Social networking—with its creation of buzz through Twitter, Facebook, and a variety of newcomers—has created yet another conduit for marketing movies. Along with the direct application of linking lookers to trailers or websites, these platforms serve to create a sort of backward spin that can encourage additional movie going, an opportunity to move the herd. Faced with a plethora of posts regarding hot new movies, social networkers can find themselves feeling out of touch if they haven’t yet seen the film everyone else is talking about.

The ever-evolving self-authorship of the Internet has also allowed for the actual individual marketing and initial success of a movie. The Blair Witch Project was made by a group of young adults for less than $65,000 and created great Internet buzz. Artisan Entertainment purchased the rights and continued to use the Internet, directly targeting teens (great horror fans). The film broke out to wider audiences and eventually generated $140 million.

However, the use of the Internet can also backfire. Marketing professionals learned a lesson back in 2001 when the Steven Spielberg/Stanley Kubrick film A.I. was released that summer. The combination of these two geniuses created huge expectations. The studios created additional buzz through an interactive game placed on the film’s website. The game achieved cult status, with buy-in from a highly interested audience base. However, the game also created high expectations of the movie. When the film failed to match those expectations, the game players, a very Internet-savvy group, created huge negative word of mouth among the very base of potential movie viewers the studio was trying to reach. As a result, A.I. failed to achieve its expected box office returns.

Planes, Trains, Automobiles—and More

Once limited to tiny airline drop-down screens several rows from your seat, offering one movie per flight, feature films have now found a home on all sorts of personal screens—on the back of the airline seat and the car seat; in your cruise-ship room; and thanks to Netflix, on laptops in the quiet car on the Acela. Although the viewing experience may still feel less than theater-perfect, these new conduits provide yet another revenue stream and are so popular with travelers that some people book certain airlines based on the entertainment equipment featured on particular models of planes.

Most major carriers now offer a selection of movies, and with the advent of DirectTV and its satellite feed, travelers now have the choice of several recent releases, along with evergreen favorites presented by various movie channels mixed in with television offerings. On most airlines, first class views films for free; back in steerage, one swipe of the credit card, and it’s all yours.

The films are highlighted in the airline’s magazines, giving each of them additional marketing exposure. The quality of the viewing may also drive later downloads by those who decide they’d like to get a better idea of what it was they just watched.

Independent Films

Not all films are produced with lavish budgets, extensive promotional departments, audience testing, and second-guessing. Independent films—films that are made outside the studio system—form a major segment of the motion picture industry.

Independent films often focus on genres, social issues, or classics, niches that might not carry the same broad-market appeal sought after by major studios. With the cost of advertising a mainstream Hollywood movie increasing from an average of $35 million in 2005 to over $50 million in 201225 (including network, cable, and satellite television; national and local newspapers; billboards; radio; online; and tie-in advertising), the breakeven point for blockbusters is climbing to the stratosphere.

25 PwC Global Entertainment and Media Outlook: 2012–2016, www.pwc.com/outlook.

With this kind of financial burden, major studios find it difficult to turn a profit on genre and classics films—the mainstay of independent movies—because their overhead is much higher than an independent producer’s.

Studios can increase their profit margins by cutting the number of films they produce, holding down production costs, and sharing more risk with financial partners. This cut in releases opens a door for the independents. Even a modest cut in output by the majors can result in about half a billion dollars in incremental box office revenue for independents.

Independent filmmakers, expert at making films on tiny budgets, can take advantage of this opportunity by making films that appeal to their target markets. Hollywood studios, spending millions to make the most broad appeal films possible, often wind up with a few big hits but plenty of boring, bland misses—not necessarily losers, just not the gains of the blockbusters.

So studio executives can’t help but lick their chops when they see the profit margins of low-budget films such as Juno (budget: $6.5 million; worldwide gross: $230 million) or Slumdog Millionaire (budget: $15 million; worldwide gross: $365 million). Creating distribution deals with independent films allows the studios to potentially reap a portion of the profits—important, when you’re also stung by big-budget flops such as Disney’s John Carter ($250 million versus a take of $72 million). Independents can take advantage of this opportunity by making films that appeal to their target markets.

The Market for Independent Films

Independent films represent about 40% of total releases, yet they only account for about 20% of total revenue. Why is there such a significant disconnect?

![]() Independent films tend to have narrower audience appeal than Hollywood films.

Independent films tend to have narrower audience appeal than Hollywood films.

![]() There are fewer screens dedicated to independent fare than to Hollywood.

There are fewer screens dedicated to independent fare than to Hollywood.

![]() Independent films may be of lower quality than major Hollywood releases simply because their production budgets are a fraction of Hollywood releases.

Independent films may be of lower quality than major Hollywood releases simply because their production budgets are a fraction of Hollywood releases.

Independent films tell stories that might only appeal to a narrow audience. Because the potential audience for independent films is smaller, it is even more difficult to get them into the theater.

And traditional big-studio marketing isn’t necessarily the answer, even if the independent had the money for it. One of the most unique aspects of the independent filmgoer is that he or she enjoys discovering a movie for him or herself. The independent audience does not like in-your-face marketing. Independent marketers are challenged to reach their audience without the audience knowing and simply can’t do a Happy Meal tie-in and expect to fill the theater.

Marketing the Independent Film

Optimally, movie producers should enlist marketing experts to consult them in every stage of production. The marketer should envision a marketing plan as soon as a project has the green light, an industry term that means the movie has been given the go-ahead.

Some examples of the value that a marketer would add to an independent production are

![]() The incorporation of market research and industry trends.

The incorporation of market research and industry trends.

![]() The use of focus groups to gauge audience perceptions of the film/scenes.

The use of focus groups to gauge audience perceptions of the film/scenes.

![]() The formulation of an advertising and release strategy to increase the chances that the film will not only have a successful opening, but will have legs—that is, will go on to earn millions of dollars.

The formulation of an advertising and release strategy to increase the chances that the film will not only have a successful opening, but will have legs—that is, will go on to earn millions of dollars.

This approach, referred to as the studio model, is virtually shunned by independent producers. They are very different from mainstream producers and are independent from outside interference. Independent filmmakers will not change the way they tell their stories and make their movies because studio executives tell them to. Independent filmmakers only care about getting their movies made. Advertising and marketing are afterthoughts. After all, the independent filmmaker believes that it is the quality of his or her film that will take market share from the majors.

So faced with smaller marketing budgets and far less marketing personnel—and openings that may consist of only three or four cities or three or four theaters—the independents must use aggressive marketing techniques to generate buzz, with the hopes of picking up a distribution deal from the studios. As discussed earlier, in the “Out the Door and Onto the Streets: Distribution” section, the studios are happy to have them—and that one-third of the film’s box office. Again, more profit for those major studio distributors without all the risk of making the movie.

Like all entertainment, independent films are faced with a limited window of opportunity. But unlike the major studios, they have a particular fan base. The average independent moviegoer is urban, well educated, with a white collar career and at a median age of 35 and a median income of $40,000 per year. Independents also enjoy a growing over-50 demographic.26

26 PwC Global Entertainment and Media Outlook: 2012–2016, www.pwc.com/outlook.

Independent movies find homes close to their base demographics, with screens often located near college towns. In addition, these films are finding increased bandwidth on cable, with channels such as Sundance, IFC, and the specialized HBO and Showtime multiplexed channels. Independents are also available through Netflix streaming and other online sources.

Word of Mouth

Independent fans are proud of “discovering” films and enjoy spreading the word. Independent filmgoers rely heavily on this word of mouth. Marketers can capitalize on this by staggering a film’s opening. A classic example, The Blair Witch Project, only opened on a handful of screens before opening wide two weeks later on July 30. Artisan knew the film would generate good word of mouth, so it opened the film in select key markets. The more people buzzed about The Blair Witch Project, the better its grosses were. In fact, the buzz was so strong, people camped outside to get tickets to the limited release. The lines themselves created such positive buzz that the Wall Street Journal called it “fierce.”

The “new” Blair Witch, a 2009 movie called Paranormal Activity, followed the same footprint. Made by young filmmakers on a shoestring, the movie blew up (to use the vernacular of the film’s audience demographic) all across the industry, generating $108 million. That success led to 2010’s Paranormal Activity 2, which took in $85 million; and 2011’s Paranormal Activity 3, $104 million.27 Paranormal Activity 4, released in 2012, has done over $140 million to date, globally. To paraphrase Walt Disney, it would appear a scream is a wish your pocketbook makes.

Internet and Independents

Independents favor the Internet because of its “discovery” aspect versus “in-your-face” marketing, again playing to the desire of the independent film fan. Websites are a crucial tool for independent films, but in keeping with the fan’s desire for something less “Hollywood” than a major film release, the website might need to be less glitzy and more unique.

Additionally, social networking sites such as Facebook allow those fans to “like” the movie, setting up another terrific word-of-mouth source. Throw in tweets by the cast, the moviemaker, or the fans, and viral marketing takes over—lots of eyeballs with no cost.

And just as with major studio releases, there are countless websites with film reviews. These reviews, with trailers either on the site or linked for viewing elsewhere, give the potential audience another link to the movie they’re hearing about.

Film Festivals

Film festivals are to independent film what power lunches are to Hollywood: a place to see and be seen, establish status, and make deals. There are nearly 300 film festivals, both competitive and noncompetitive, in the U.S., with new ones arriving every year.

The goal of the competitive film-festival entrant is to have his film picked up by leading independent distributors such as Lionsgate, The Weinstein Company, Focus Features, Fox Searchlight, or Sony Pictures Classics. Today, even cable channels like Sundance and IFC are looking for new films.

More than half of the films shown at these festivals never get theatrical release. Some go direct to home video through the remaining retail video outlets or stream directly to the consumer over Netflix. Festivals are important for showcasing new talent, testing marketing programs, gaining research, building word of mouth, garnering awards, and finding distribution deals. Every successful independent film, released in either narrow or rolling wide distribution, has been launched or shown at one or more film festivals.

The most famous of the festivals that focus on independent movies, Sundance, was founded as the Utah/U.S. Film Festival in 1978, with then-hot young star Robert Redford as its chairman. Fast forward to 1984, and the management of the festival is taken over by the Sundance Institute, a training facility for newbie writers and aspiring directors founded by Redford in 1981. Sundance set the standard for independent film festivals and continues to enjoy its prestigious rank.

Though Sundance began as a place for non-Hollywood filmmakers to show their work, the festival became a scene, drawing Hollywood by the private jet-load. But the festival has recently reset its course, adding a competition, Next, for microbudget films, staying true to its roots.

Drawing from thousands of submissions, the festival chooses 110–120 feature films and 70–80 short films to be shown.

Notables who got their start at Sundance include directors Quentin Tarantino, Steven Soderbergh, and Jim Jarmusch. Films that started successful runs via Sundance include Saw; The Blair Witch Project; Reservoir Dogs; Little Miss Sunshine; Sex, Lies, and Videotape; and Napoleon Dynamite.

The Tribeca Film Festival, held in New York, was cofounded by Robert de Niro, Jane Rosenthal, and Craig Hatkoff, as a response to the 9/11 tragedy. The intent was to help rebuild Lower Manhattan while offering a different film festival experience from Sundance.

Now in its eleventh year, the Tribeca Film Festival draws filmmakers, as well as artists and musicians.