5. The Rising Tide of Technology: Television Content Delivery in a Digital Age

In this chapter, we discuss the traditional and emerging platforms, including multichannel video platform distribution (MVPD), covering those providers who utilize set-top boxes as their primary link to the consumer, delivering basic, premium, pay-per-view, and on-demand services. This includes cable and direct broadcast satellite, as well as wireline (telco) video providers. This discussion includes Internet-protocol television, which delivers live and time-shifted television and video-on-demand and so-called “over the top” content, delivered via the Internet through third-party services such as Netflix and Hulu and received on devices such as smartphones, personal computers, smart televisions, and gaming consoles.

But beware: All of this is changing by the hour. Although the (fading?) standard of the industry is the set-top box, new advances in technology, along with the big data gathering ability of the Internet, have the television industry in the midst of a tectonic disruption, with marketing professionals welcoming an avalanche of new ways to identify, reach, and track consumers.

The Multichannel Video Universe

Historically, media content was designed for a single platform set—movies for the theater and television shows for the small screen. That paradigm was broken long ago, as movies became a prime piece of the cable television experience.

Now, with a proliferation of platforms—cable, satellite, Internet, mobile devices—the game is different. Technology is changing by day, disrupting the business models of content deliverers. And it is no easier for content providers. They must start each project with a strategy that addresses all the platforms, all the possible interactions, and all the sequencing to optimize both the content experience and the business outcome. The consumer is now king. They will watch where they want to, when they want to. If you can’t keep up, you’re dead. Marketing professionals must understand all of the options to fully exploit the product’s potential, leading to full monetization of the brand. It is one hefty chunk to chew on, but what we cover here is central to your understanding of what is happening in the entertainment marketing ecosystem.

Let’s start at the beginning: cable television.

Over the Cable or Through the Box

Few consumers today think of roof-mounted antennae bringing signal to their televisions, although HD signal can still be delivered to your living room for free, as long as you buy an HD antenna (possibly the best-kept secret in television-crazy America). As of 2012, 86% of American households subscribe to some kind of pay television, whether it is delivered via cable, satellite, or telephone wire.

This extraordinary penetration offers marketing professionals a direct conduit to specific audiences via an ever-growing array of content specifically developed to appeal to particular market segments. MVPD—what we often refer to generically as “cable television”—is currently the primary battlefield for the control of entertainment consumers and their pocketbooks, utilizing the set-top box as the centerpiece of data transmission and collection.

As we discuss later in this chapter, the set-top box is meeting many emerging challenges. But at the time being, cable is still the second-leading distribution point of television programming and is still hot on the tail of network broadcasting.

The simplest way to think about the business of MVPD versus traditional network broadcasters is this:

![]() Network broadcasters send 24 hours’ worth of specific programming—one program per viewing segment of the day—to the local stations and affiliates we spoke of in the last chapter, via over-the-air digital radio signal. This content is supported by advertising, so viewers pay nothing to receive the signals. The only equipment necessary is the receiver in the form of a television set and an HD antenna.

Network broadcasters send 24 hours’ worth of specific programming—one program per viewing segment of the day—to the local stations and affiliates we spoke of in the last chapter, via over-the-air digital radio signal. This content is supported by advertising, so viewers pay nothing to receive the signals. The only equipment necessary is the receiver in the form of a television set and an HD antenna.

![]() MVPDs deliver many different networks and services to paying subscribers. This includes the traditional network broadcasts, along with hundreds of different programs and nonbroadcast networks, all packed into that same 24-hour period. MVPDs also offer additional consumer-chosen products and services. The offering is delivered via two primary modes:

MVPDs deliver many different networks and services to paying subscribers. This includes the traditional network broadcasts, along with hundreds of different programs and nonbroadcast networks, all packed into that same 24-hour period. MVPDs also offer additional consumer-chosen products and services. The offering is delivered via two primary modes:

![]() Fiber-optic cable, buried below ground or strung along the road with telephone wire, then connected directly to the subscriber’s location

Fiber-optic cable, buried below ground or strung along the road with telephone wire, then connected directly to the subscriber’s location

![]() Satellite transmission, with content downloaded to a dish mounted on the side of the house, building, or boat

Satellite transmission, with content downloaded to a dish mounted on the side of the house, building, or boat

The channel lineup delivered by cable or satellite may be somewhat similar—though each has its own claim to unique features—but the businesses are different.

![]() Cable operators work within specific territories, based on deals worked with various municipalities to deliver content to the local citizenry. These U.S. operators install and maintain a vast infrastructure of connectivity, centered on over 7,000 headends, the central receiving point where programming is delivered via satellite, fiber-optic feed, and/or antenna.1 All programming—including broadcast networks received and retransmitted to cable subscribers—is then delivered to the subscriber over thousands of miles of cable.

Cable operators work within specific territories, based on deals worked with various municipalities to deliver content to the local citizenry. These U.S. operators install and maintain a vast infrastructure of connectivity, centered on over 7,000 headends, the central receiving point where programming is delivered via satellite, fiber-optic feed, and/or antenna.1 All programming—including broadcast networks received and retransmitted to cable subscribers—is then delivered to the subscriber over thousands of miles of cable.

1 National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA).

![]() Direct broadcast satellite companies, a niche primarily served by DirectTV and DISH, send digital signals to subscribers all over the country (and the waters surrounding the country). There are no specific municipal boundaries. Content is uploaded and downloaded via satellites to the subscriber’s satellite dish. The company’s infrastructure costs are tied up in the transmission and reception of signal—the satellites—versus the fiber-optic highways of the cable companies.

Direct broadcast satellite companies, a niche primarily served by DirectTV and DISH, send digital signals to subscribers all over the country (and the waters surrounding the country). There are no specific municipal boundaries. Content is uploaded and downloaded via satellites to the subscriber’s satellite dish. The company’s infrastructure costs are tied up in the transmission and reception of signal—the satellites—versus the fiber-optic highways of the cable companies.

![]() Telco companies—AT&T and Verizon—utilize existing telephone wire and fiber optic cable to deliver their full-Internet protocol television products and DSL Internet.

Telco companies—AT&T and Verizon—utilize existing telephone wire and fiber optic cable to deliver their full-Internet protocol television products and DSL Internet.

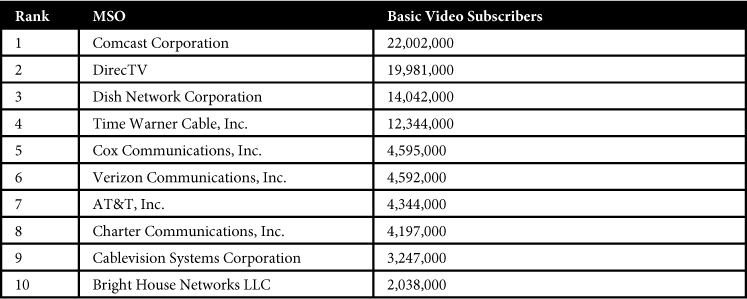

Together, these three forms of MVPD reach well over 100 million subscribers.2 Though there are over 800 cable companies throughout the United States, the industry is dominated by Multiple Service Operators (MSOs), which operate many cable systems in many different municipalities (see Exhibit 5-1).

2 National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA).

The industry as a whole generates an estimated $150 billion,3 including video subscriptions, advertising revenue, and a variety of services that we address later.

3 The exact revenue of what we call the cable industry is difficult to pin down, as some companies are not publicly held and therefore do not release revenue data.

The continuing growth in content consumption—the ever-expanding entertainment marketing phenomenon—along with mind-boggling shifts in content delivery, is opening new profit pathways, and it seems that everyone is trying to get a piece of the action. As we put this chapter together, there are a number of technology companies—including Sony, Intel, and Apple, which have traditionally been involved in creating devices—that are seriously considering entering the world of the conduit, joining the systems described here in delivering content. How might that happen? Read on. We get to that in a bit.

Before we move into the finer points of this key entertainment universe, it’s important to understand a bit about the background of cable, for buried in its history are regulations that will define the future of broadband and its new hot competitor, mobile content delivery.

The Link Between Then and Now

John Wanamaker, a nineteenth-century titan of retailing (often referred to as one of the fathers of modern-day marketing) once said, “Half the money we spend on advertising is wasted. The problem is, we don’t know which half.” Mr. Wanamaker would have loved set-top boxes, those winking, blinking basic-black receivers connected to your television, delivering more channels than you can watch—and providing the operators with specific audience data sliced and diced to the slimmest of profiles.

“Cable television” originally referred to a service that was literally linked, by a cable, to a tower or antenna tall enough and powerful enough to grab the radio signal of the nearby television stations and broadcast networks. The collected content was delivered to local subscribers by what was known as Community Antenna TV (CATV). In the earliest of cable days, this linkage may have been put in place by a local entrepreneur—a television repairman, an appliance salesman—who saw the business potential of creating a community network in any of the hundreds of towns and villages hidden behind mountains, down in hollows, or behind any structure that blocked signals.

Cable television is a sterling example of necessity birthing invention, leading to easy access, wide selection, vast wealth, and continuing controversy. Those canny pioneers, having created a healthy cash cow in their local community, looked for ways to fatten their business. Once they found the technology that allowed them to grab the distant signals of the network broadcasters, it didn’t take long for the networks to start crying foul. After all, those then-tiny cable companies were grabbing the signal and redistributing it to the community for a fee—and the networks weren’t getting a penny out of that.

The networks did not sit still, busying their lawyers with lawsuits and lobbying. The FCC responded, issuing rulings in 1962 that limited cable’s reach.

You may be wondering why the FCC would take such a stance, especially if you’ve never known anything but cable television. The crux of the matter was this: originally created to sustain and promote broadcast radio, and later, broadcast television, the FCC had spent the better part of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s creating a regulated broadcast industry that would serve the best interests of the public. Remember, the programming that was broadcast was free—paid for by the advertising sold by the networks. Along came cable, making money by utilizing those signals and now trying to move into markets recently cleaned up by the FCC.

In a nutshell (although it is certainly far more complex than this), the FCC decided it was its duty to protect the consumer and the investment of the networks, which were serving the people. To do so, it had to regulate certain aspects of cable as well.

Over the next two decades, the legal battles raged. The FCC handed down policy statements and rulings that

![]() Forced cable to carry local programming (known as “must carry,” which pops up later in our discussion), a move that was meant to underscore cable’s role as a local, not a national, provider.

Forced cable to carry local programming (known as “must carry,” which pops up later in our discussion), a move that was meant to underscore cable’s role as a local, not a national, provider.

![]() Made cable companies provide channels that were known as local access, requiring them to provide studios and equipment for programming created locally.

Made cable companies provide channels that were known as local access, requiring them to provide studios and equipment for programming created locally.

![]() Limited cable from importing anything that duplicated what was carried on local stations.

Limited cable from importing anything that duplicated what was carried on local stations.

![]() Kept cable from entering the top 100 markets.

Kept cable from entering the top 100 markets.

![]() Prohibited cable companies from showing movies that were less than five years old or sporting events that had been broadcast within the previous five years.

Prohibited cable companies from showing movies that were less than five years old or sporting events that had been broadcast within the previous five years.

Yes, all of this is true, and certainly a little hard to believe in the current environment. But all of this served to advance the FCC’s policy that cable should be a local presence and that the networks should be protected.

In the end, the legal battleship was turned around. As reported by the Museum of Broadcast Communications,

...think tanks such as Rand Corp. heralded cable television’s potential for creating a wide variety of social, educational, political and entertainment services beneficial to society. These constituencies objected to the FCC’s policies because they seemed to inhibit the promise of the ‘new technology.’ Ralph Lee Smith’s 1972 book, Wired Nation, captured many people’s imaginations with its scenarios of revolutionary possibilities cable television could offer if only it were regulated in a more visionary fashion, particularly one that supported developing the two-way capabilities of cable and moving it toward more participatory applications. The discourse of cable as a cornucopia, as progress, as an electronic future captivated many. Interest in new technology and a concerted effort by the industry spurred a national debate, advancing the idea that cable must be allowed to grow in order to deliver consumers a wide variety of social, educational, political and entertainment services beneficial to society.4

4 www.museum.tv, the Museum of Broadcast Communications, United States: Cable Television.

Regulations began to relax, but it wasn’t clear sailing quite yet. Cable was still limited or denied in its ability to carry the distant microwave signals of the broadcast networks, as well as recent movies and sporting events. Two landmark events finally brought this stranglehold to an end.

Beam Me Up, Scotty: Cable Enters the Satellite Era

The first significant shift began with the creation of Home Box Office, originally billed as the Green Channel, by Charles Dolan, owner of Manhattan Sterling Cable, a New York City provider. He approached publishing giant Time-Life (now morphed into Time Warner) with the idea of a subscription service that would show movies and sporting events. Time-Life took a chance on the idea, launching what came to be known as Home Box Office in 1972. HBO’s original programming consisted of movies and sporting events and was only broadcast nine hours a day, utilizing a series of microwave towers.

Time-Life acquired control of Sterling and renamed it Manhattan Cable Television, replacing Dolan with Gerald Levin as president of HBO. (Don’t feel bad for Mr. Dolan; he went on to organize Cablevision, now one of the top 10 MSOs. In 1980, he also spearheaded the creation of AMC Networks Inc., which today includes AMC, WEtv, IFC, and Sundance Channel, as well as the independent film business, IFC Entertainment.)

Levin built HBO into the fastest-growing pay TV service in America, and in 1975, he blew the doors open by switching the transmission process from microwave antenna to commercial telecommunications satellite. This was a critical move, for the capture of broadcast’s microwave transmissions was no longer an issue. HBO and soon other programming from other entrepreneurs could now be beamed around the country. Time-Life/HBO furthered this leap by paying for the large satellite dishes that were needed for capturing the signal.

Now comes the huge leap forward: HBO, tired of being limited in content and hours, took the FCC to court—and won. In a landmark decision, one that continues to create mega-waves in the industry today, the court ruled that cable television resembled newspapers more than broadcasting, in that it “packaged content for publication,” and therefore deserved more protection under the First Amendment.

This electronic publisher status was reaffirmed in another case in 1979, United States v. Midwest Video Corp. The cable industry continues to argue its legal cases based on this ruling today. You’ll see how this has come to the forefront once again when we discuss new technologies entering the marketplace.

FCC regulations were now falling on a consistent basis. Satellite transmission opened the door for programming. The next decade saw the uplink of Ted Turner’s Superstation WTBS, later to become TBS; Mr. Turner’s entry into the news market, CNN; The Christian Broadcast Network (CBN), now ABC Family; Showtime; Nickelodeon; MTV; The Movie Channel. Getty Oil launched the Sports Programming Network, which is now Disney’s ESPN.

But the biggest shift came in the 1990s.

Telecommunications Act of 1996

Prior to 1996, the FCC felt restrictions on broadcast station ownership would provide greater competition and therefore a greater diversity of voices and programming choice. This was determined to be in the best interests of the public and suggested the possibility of an increase in the quality of entertainment offered. Although the FCC had picked away at cable with new regulations here and there, the Telecommunications Act of 19965 was the first wholesale update to telecommunications law in 62 years—amazing given the rapidity of change within the industry. The implications to cable and satellite TV were significant.

5 A complete copy of the law can be downloaded in Adobe PDF format at the Federal Communications Commission’s website (www.fcc.gov).

With the passage of the Act, the broadcast networks were able to expand their owned and operated stations from coverage of 25% of U.S. households to 35%. This 10% increase encouraged some consolidation and motivated significant station sales. The changes wrought by the Act included allowing for multiple radio station ownership in a market and cross-ownership of several media in one market, such as newspapers, radio, and TV stations, a huge shift in a previously monopoly-adverse stance.

Take a moment to consider this: Markets that were once served by several independent outlets, over several platforms, providing different views on important issues, could now be relegated to having one large conglomerate who could basically own broad swaths of that market’s media. This may be good for business, but to this day, there are those who decry the independent thought that flourished prior to cross-ownership.

The Telecommunications Act was very good for marketing. It eliminated the long-standing restriction on network ownership of cable television systems. This opened the door for media companies with multiple stations to blanket a local audience on behalf of their advertisers with efficient cost-per-thousand media planning offers. Media companies could now provide both in-depth coverage of a local audience and synergy between their properties, making for enormous competitive clout.

Continued support of the first amendment’s “Freedom of Speech” enabled the cable industry to enjoy enormous freedom in selection of content, as well as adding services that would be governed by free-market competition. By providing a strong force for deregulation, the Act also set the groundwork for the combination of cable operators and Internet suppliers. Companies could now plan the marketing and sale of converging media vehicles.

Furthermore, the Act allowed for interactive programming and the ability of cable and telephone companies to offer voice and video transmission on the same wire. It also required any sexually explicit service to be scrambled to prevent reception by nonsubscribers but allowed this content to be available between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. Most important to the cable companies, the Act eliminated any control over the rates for service tiers, packages, or single-channel services or discounted rates for multiple dwelling units, as long as it was not construed as predatory pricing designed to push all other competitors out of the market—this, in an era of rate regulation of public utilities.

All of this left cable in a terrific position, but it also left the business with an element that continues to have an impact on both the bottom line and the programming offered to the subscriber: the retransmission fees operators must pay to programmers to carry the programming the subscribers most want to see.

Retransmission Consent

As a provision of the 1992 Cable Protection and Competition Act, all MVPDs must obtain permission from broadcasters before carrying their programs. This typically also involves a fee being paid to the broadcaster (the “retransmission fee”). The MVPD may choose not to carry the programming but must always take into account the desire of the subscriber base in making those decisions or risk losing those customers.

The constant push-pull between the cable operator and the cable programmer often plays itself out in public. The programmer may ask for more money than the operator would like to pay, and then one or the other decides to take the fight to the public—the subscriber. Full page ads start to appear, blaming the cable network for getting rid of an audience favorite; the programmer will attack with their own salvo, telling subscribers what impact the increased costs will have on subscription fees.

One of the most famous cases of this nature occurred between Disney and Time Warner in May of 2000,6 a knock-down-drag-out that affirmed the power of the Disney brand while blackening the eye of Time Warner. A more recent example occurred between Time Warner and AMC, home of the popular Mad Men series. Fox also battled with Warner Cable; ESPN slugged it out with Comcast. The result of these battles is pretty much the same: Negotiations ensue, agreements are reached, but the battles are rarely ended quickly.

6 For much more detail, see Stewart, James B., “Mousetrap: What Time Warner didn’t consider when it unplugged Disney,” The New Yorker, July 31, 2000.

What’s at stake in all of this is a huge amount of money. Retransmission fees are projected to skyrocket in the coming years, for all three modes of delivery: cable, satellite, and telco, as demonstrated in Exhibit 5-2.

This, of course, is huge for the broadcasters. SNL Kagan analysis indicates that by 2018, the projected $6.05 billion of retransmission revenue would be approximately 23% of the expected $26.2 billion in TV station ad revenue.7

7 “Retrans Fees Seen Hitting $6B By 2018,” TVNewsCheck, November 5, 2012.

The fees may seem staggering, but the content—the programming—is the heart of the cable business model. The depth and breadth of the product offering is what brings subscribers by the millions. The ability to reach those subscribers is what brings the advertisers, who spend billions.

Cable’s Marketing Advantage: Reach and Segmentation

The heart of cable marketing is its reach and ability to cozy into niche markets. Before we describe the channels by category and examine their marketing philosophy, consider the range of coverage provided. Cable offers advertisers the opportunity to reach over 280 million men, women, and children in about 100 million television households. Once seen as an exclusively mass audience with a singular mentality and a plain-vanilla entertainment orientation, cable channels deliver advertisers a diversity of age, race, religion, country of origin, intellectual leanings, and genre of entertainment.

In terms of general categories, cable offers a doorway into some very specific and desirable markets:

![]() The executive or family that has a strong interest in the financial markets, managing its own portfolios, or staying ahead of the vast quantity of business news has a choice of CNBC, CNNfn, MSNBC, and Bloomberg via DIRECTV. In addition, each of these channels offers constant connectivity through its own websites, mobile apps, and email streaming to hard-core viewers.

The executive or family that has a strong interest in the financial markets, managing its own portfolios, or staying ahead of the vast quantity of business news has a choice of CNBC, CNNfn, MSNBC, and Bloomberg via DIRECTV. In addition, each of these channels offers constant connectivity through its own websites, mobile apps, and email streaming to hard-core viewers.

![]() Women are at least 50% of the U.S. workforce and are major decision-makers in the purchase of new homes, cars, family market-basket products, and clothing. Though they are certainly a part of the audience watching any of the business cable channels, they will also be found viewing the Food Network, Lifetime, and WE (Women’s Entertainment).

Women are at least 50% of the U.S. workforce and are major decision-makers in the purchase of new homes, cars, family market-basket products, and clothing. Though they are certainly a part of the audience watching any of the business cable channels, they will also be found viewing the Food Network, Lifetime, and WE (Women’s Entertainment).

![]() Teenagers, who form an audience with significant discretionary time and disposable income, are drawn to MTV, VH1, Nick at Night, and the various movie channels. All are strong platforms for the 16 to 25-year-old demographic, with Comedy Central expanding the upper end to 35+ years of age with some of the more sophisticated and graphic-language programs.

Teenagers, who form an audience with significant discretionary time and disposable income, are drawn to MTV, VH1, Nick at Night, and the various movie channels. All are strong platforms for the 16 to 25-year-old demographic, with Comedy Central expanding the upper end to 35+ years of age with some of the more sophisticated and graphic-language programs.

![]() Although broadcast television has an obligation required by law to provide a certain amount of educational programming for children, basic cable provides the Cartoon Network, Animal Planet, Discovery, Fox Family, and Nickelodeon. Premium cable provides The Disney Channel for an extra charge.

Although broadcast television has an obligation required by law to provide a certain amount of educational programming for children, basic cable provides the Cartoon Network, Animal Planet, Discovery, Fox Family, and Nickelodeon. Premium cable provides The Disney Channel for an extra charge.

![]() Adults from ages 25 to 45 interested in less-than-intellectually-challenging entertainment are drawn to A&E, with Duck Dynasty and Storage Wars, or Bravo, which has become the home of such cultural fare as The Real Housewives series.

Adults from ages 25 to 45 interested in less-than-intellectually-challenging entertainment are drawn to A&E, with Duck Dynasty and Storage Wars, or Bravo, which has become the home of such cultural fare as The Real Housewives series.

![]() If you want to reach males 18 to 49—or almost anyone with a sports interest—advertise on ESPN. Clearly one of the most valuable properties Disney obtained in the acquisition of ABC, ESPN has been one of the most widely watched basic channels and a leader among sports channels in general. Others have followed in ESPN’s financially rewarding footsteps, including the Golf Channel, NBCSports, Fox Sports, Madison Square Garden Network, and Sports Channel from the Rainbow Programming division of Cablevision.

If you want to reach males 18 to 49—or almost anyone with a sports interest—advertise on ESPN. Clearly one of the most valuable properties Disney obtained in the acquisition of ABC, ESPN has been one of the most widely watched basic channels and a leader among sports channels in general. Others have followed in ESPN’s financially rewarding footsteps, including the Golf Channel, NBCSports, Fox Sports, Madison Square Garden Network, and Sports Channel from the Rainbow Programming division of Cablevision.

Minority Reach

One of the defining characteristics of cable television is that it can attract and appeal to the ethnic and minority segments of television-viewing households. The Hispanic and African-American populations represent two specific focus points for the cable industry:

![]() Hispanics, one of the fastest growing populations in the U.S., will soon represent one-third of all television viewers. Hispanics have an acknowledged high interest in entertainment. Many family members speak predominantly Spanish, and, taken as a whole, the national demographic of Hispanics has a significant gross disposable income as well as a household budget in the billions-of-dollars range. The population growth is in major metropolitan areas in parts of Texas, California, Florida, and New York. Univision, the fifth most important network in the U.S., and SIN networks provide quality programming from Mexico, Latin America, and Spain. These networks use Spanish-language newspapers, magazines, and public transportation posters to identify Spanish soap opera stars and historical documentaries for their countries of origin.

Hispanics, one of the fastest growing populations in the U.S., will soon represent one-third of all television viewers. Hispanics have an acknowledged high interest in entertainment. Many family members speak predominantly Spanish, and, taken as a whole, the national demographic of Hispanics has a significant gross disposable income as well as a household budget in the billions-of-dollars range. The population growth is in major metropolitan areas in parts of Texas, California, Florida, and New York. Univision, the fifth most important network in the U.S., and SIN networks provide quality programming from Mexico, Latin America, and Spain. These networks use Spanish-language newspapers, magazines, and public transportation posters to identify Spanish soap opera stars and historical documentaries for their countries of origin.

![]() Robert Johnson launched his dream in 1980 with a cable station dedicated to entertainment skewed to an African-American audience: BET. By the year 2000, the station was reaching 60 million total households in the U.S. and had twice been ranked by Forbes among “America’s best small companies.”

Robert Johnson launched his dream in 1980 with a cable station dedicated to entertainment skewed to an African-American audience: BET. By the year 2000, the station was reaching 60 million total households in the U.S. and had twice been ranked by Forbes among “America’s best small companies.”

What are the implications for marketers in attempting to reach ethnic and minority segments? Understanding the slang or language is a necessity, as it is in any global marketing. Additionally, the use of ethnic and minority actors and actresses or distinctive voiceovers in radio, television commercials, and print advertising is often the difference between success and embarrassing failure.

More and more communication companies have developed specialty advertising and public relations agencies whose management and staff are from minority groups, who speak the language and understand the mores and culture of these valuable audience segments. Young & Rubicam (Y&R), now part of a global communications company based in England, has two such specialty units. The Bravo group works only on Hispanic advertising to run in targeted media; they educate their non-Hispanic advertisers eager to reach these markets about the difference between Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, and other subsegmented forms of the Spanish culture. Chang and Lee, another Y&R unit, specializes in advertising to various Asian audiences on cable channels that reach Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and other important ethnic groups.

Case in Point: Viacom Takes the BET

The success of minority-focused cable channels did not go unnoticed by the Big Brands. Within months after BET’s anniversary celebration, it became clear the network was about to change ownership. The announcement that Viacom—the third largest media and entertainment conglomerate—had plans to purchase BET and turn it into a powerhouse brand was met with mixed reviews. The primary concern was a backlash from BET viewers, given that the largest African-American owned and operated media company was about to be acquired by a predominantly white company.

In acquiring BET, Viacom saw an opportunity to provide proven marketing success in the ethnic audience sector and expand BET’s distribution. The marketing synergy and understanding of this demographic were based on current success within the various operations at Viacom. CBS had the highest ratings of any network in black households, UPN had an entire evening of black-themed shows, and Showtime had made a commitment to African-American programming.

Viacom, with many cable programmers under its umbrella, could provide clout in marketing BET to the MSOs and independent cable operators in ethnic communities. It also provided the resources needed to develop quality programming for a rapidly growing middle-and upper-class African-American community. The advantage of Viacom for BET’s consumer marketing was the use of its varied media ownership, including billboards, radio stations, broadcast networks, and other cable programmers.

Viacom made an excellent wager on BET. Black middle class households (average income of $50,000 and above) have increased by 358% since 1990, while black upper class households (average of $100,000 and above) have increased by 128%.8 Viacom reached an underserved market, while balancing existing synergy within all brand units—an excellent long-term strategy.

8 “In Plain Sight: The Black Consumer Opportunity,” a special supplement to Advertising Age, April 23, 2012.

The Universal Audience

Cable is certainly not entirely focused on niches. There is a strong universal audience, as basic cable reaches 86% of television households. Many viewers simply shift their allegiance from network to cable. They have become a displaced mass audience shared by TBS, American Movie Classics, TNT, Fox Family, and the other basic channels.

One of the major breakthroughs in cable was the launch of USA Network, with Kay Koplovitz as the CEO. Koplovitz, one of the first women to reach a senior management position in the cable industry, came from a strong programming and marketing background. She was one of the first to capture valuable programming from the syndication auctions by the broadcast networks and ran many seasons of Murder, She Wrote; M*A*S*H; and other mass-appeal products. She also gained a significant male and teenage audience with expanded coverage of the World Wrestling Foundation.

One of the difficulties—and strengths—behind USA’s growth was its ownership, divided equally between Universal and Viacom. In only a few years, USA Network became the leading cable channel, with over 26 million viewers at the height of its success. In its search for channel expansion, USA management recognized the value of a special-interest audience that would allow them to use their marketing muscle and cable affiliate relationships. From information shared by their Universal parent, USA Network’s marketing management became aware of the strong following for Star Wars, Star Trek, and other science fiction films. It was no surprise when USA Network launched the SciFi Channel and built it a great audience following by marketing to “Trekkies” and readers of science fiction literature.

Universal, of course, was purchased by NBC, which then merged with Comcast. And what did SciFi finally realize? That to grow, it had to expand past science fiction programming. The channel changed its name to SyFy in 2009. One other advantage of the name change? “SciFi” was too generic and could not be easily trademarked. Not the case with SyFy.

Business Building: Stretching the Brand

Strategy is an important element of the cable industry. With so many niches to service, operators and programmers alike find themselves in a constant chess game. Part of the game includes a classic marketing technique: brand extension.

There are several examples of this maneuver in the cable industry. A&E, which originally stood for “arts and entertainment,” focused on PBS-level programming in its early years. The network created Biography, an internally developed product directed at a segment of the basic network audience. From research of the unique interests of their viewer constituency and the acquisition of book club lists, A&E identified another target audience, an enormous population of history buffs. This led them to the next successful brand extension, the History Channel. The network cross-promoted these new channels on the mother channel, A&E. As we mentioned earlier, A&E now focuses on less high-toned entertainment. The network is now primarily known for programming that would make Newton Minnow—the FCC Chairman who, in 1961, proclaimed that television was a “vast wasteland”—say, “I told you so.”

But business is business. A&E’s new approach has shifted its average audience age a remarkable 19 years younger—to age 40—than it had been in 2003.9

9 TVbyTheNumbers.com, “A&E Announces 2010–2011 Original Programming,” May 5, 2010.

Bravo originally focused on a menu similar to A&E. The network added town meeting discussions with actors and actresses in their Actors Studio program, especially geared to film buffs interested in anything about movies. When Bravo management (within the parent company at Cablevision) established this Actors Studio brand, Kathy Dore, then president, and her marketing executive (now president), Ed Carroll, set to work building their own line extension. The rumor that Sundance Institute was searching for a home for its independent film cable outlet, the Sundance Channel, motivated Bravo to quickly launch its own independent film channel, aptly named IFC. Sundance Channel arrived on the cable spectrum soon after.

Bravo is now the home of reality television, including franchises such as Top Chef and Real Housewives. Eleven new Bravo reality shows were announced at the 2012 upfronts.

ESPN also recognized that discrete audiences existed within its loyal sports-addicted viewership. Thus, ESPN2 and ESPN Classic were born to meet the demands of special audiences, including college football, basketball, international soccer, the WNBA (women’s basketball), and the Gen X (and onward) craze, extreme or X-sports. Sponsors were prepared to advertise and market their products to these special audiences. For instance, Pepsi’s Mountain Dew brand built an impressive soft drink market by becoming the lead sponsor of extreme sports competitions.

Live sports are one area where commercials are still relatively safe. The value of this niche has skyrocketed as new technologies have allowed viewers to record and time-shift programming, opening the door for manipulation of advertising—as in, just plain skipping past the commercials. There is little to be gained from recording a live sports event, unless you truly don’t care about the competitive aspect or have no problem with watching the event even though you may already know who won.

This desire to have a bulwark against commercial-hopping has resulted in some extraordinary contracts being put together between conduits and teams/leagues. The most recent eye-popper is the deal announced in January of 2013, between the LA Dodgers and Time Warner Cable, for $7 billion over 25 years.

What makes this deal particularly interesting to our discussion is that it frames the ever-growing value of entertainment brands in relationship to content conduits. The Dodgers were sold in 2012 for an astounding $2 billion-plus, almost double the earlier record of $1.1 billion paid for the Miami Dolphins. Around the country, the immediate reaction was, “You have GOT to be kidding me.” However, most of those folks, we would assume, may now be thinking differently—some happily so. After all, if the Dodgers are now worth $2 billion-plus, what does that mean for other major market teams?

The chart in Exhibit 5-3 demonstrates some of the most recent broadcast sports deals that have been inked in the last few years. Keep in mind that most of the following deals are for entire leagues, not just one team, with the exception of the deals with the LA Lakers (basketball) and the LA Angels (baseball). Perhaps it’s just too difficult to actually drive to an LA sporting event.

Exhibit 5-3 Recent Major Sports Deals

Source: Will Richmond, 80 Billion Reasons Why Pay-TV Will Become Even More Expensive, www.videonuze.com, 2012

This increased value of sports programming is leading to increased subscription fees. Multibillion dollar cable contracts with local or national sports teams must be paid for somehow. An additional $3 to $5 per month, per subscriber—whether you watch sports or not—is often the answer.

Beyond Basic

New technologies now allow consumers to receive state-of-the-art services, including digital video and audio, HDTV, broadband Internet, pay-per-view events, and on-demand and premium programming, with over 900 channels available. So-called “triple play” packages bring television, Internet, and telephone into the home.

All of this brings fees well above the base rate. These important sources of revenue include the following products.

Premium Cable Channels

Cable packages offer a plethora of premium viewing, with several choices of all-movie channels, as well as selected children’s channels offered by most cable operators either individually or as a package for a discounted fee. These include HBO, HBO2, HBO3, Showtime 1, Showtime 2, Cinemax, Disney, Encore, Starz, The Movie Channel, Sundance, and the Independent Film Channel (IFC). In some markets, the two “arts” movie channels, Sundance and IFC, are offered as premium channels because of the often violent or sexual nature of the movies. And speaking of sex, the once-discrete Playboy and Spice listings have been joined by many more channels with far more graphic titles, now shown on home cable guides.

Digital Video Recorder (DVR)

As we discussed in the last chapter, DVRs have had a significant impact on viewing habits.

At one time, home viewers needed to purchase a DVR device/service such as TiVo to time shift, but cable providers saw the wisdom of keeping control and added the technology to the set-top box, for an additional fee. DVRs also offer the viewer the ability to fast-forward through commercials. A recent development introduced by DISH, the Hopper, allows viewers to record entire prime-time schedules of all four major networks. Though the viewer still needs to fast-forward the commercials in the first 48 hours, after that time, the commercials simply disappear from sight, replaced with a brief black screen. DISH executives claim a high demand for the service but are unwilling to go on the record with specific numbers.

On Demand/IPTV

On-demand offers streamed programming, available at the viewer’s discretion. Products offered include both movies and television shows. Viewers might or might not be charged, depending on the genesis of the programming. For example, Showtime shows may be free to Showtime subscribers but not to those who haven’t paid for the Showtime channels.

Pay-Per-View

Pay-per-view (PPV) was the original conduit for alternative time-viewing, with recently released movies offered to cable customers for a charge slightly less than the cost of a movie ticket—without the fee for a babysitter, parking, and popcorn. Cable battled the rental industry for control of this segment, but all of the players—cable, Blockbuster, Netflix—saw their business models morph dramatically with the introduction of IPTV, just mentioned. Cable grabbed hold of the technology; Blockbuster saw its dominance crumble and its stores close, and Netflix—well, you’ll be hearing more about Netflix in a bit.

PPV still brings in sizable chunks of cash in the area of boxing and extreme sports. In 2007, HBO sold 4,800,000 PPV buys for the Mayweather-Hatton fight, with $255,000,000 in sales.10 The World Wrestling Foundation (WWF) has also built its business on PPV but has recently seen the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) match their numbers. As a whole, HBO Boxing, WWF, and UFC are the bulk of today’s PPV.

10 “Mayweather-Hatton Pay-Per-View a Smashing Success,” http://sports.espn.go.com/sports/boxing/news

Cable Radio

Over 100 radio stations are making their way into households today through an entirely different conduit: cable. Among the benefits are

![]() Clear, static-free, commercial-free, digital-quality sound on today’s higher quality home entertainment systems

Clear, static-free, commercial-free, digital-quality sound on today’s higher quality home entertainment systems

![]() The name of the artist, label, and song scrolling on the TV screen

The name of the artist, label, and song scrolling on the TV screen

![]() Focused listening selections from music channels specializing in jazz, rock, country, alternative country, Tejano, salsa, metal, classics, oldies, and many more

Focused listening selections from music channels specializing in jazz, rock, country, alternative country, Tejano, salsa, metal, classics, oldies, and many more

Each channel offers music not often available on commercial radio stations. This music is sometimes packaged as a unique program. However, as you might imagine, new mobile music services such as Pandora present a strong challenge to this concept.

Media, Marketing, and Money

Control of the airwaves is just as important on cable as it is on network TV. Channels must fight the continuing battle for the cable version of “shelf space.” Regardless of the discrete audiences attracted to an individual station or a group of stations, it is important to note that every channel competes with every other channel.

The difference is that on cable, a media conglomerate may develop and control many different channels, as opposed to one network. Successful media marketing in the cable industry is driven by MSOs that can package a variety of channels—reaching a variety of audiences—so that advertisers can expand their reach beyond the mass appeal of networks.

Think of it this way: A broadcast network might have 20 primetime shows hitting four demographic groups in the course of a week, in perhaps 5 primetime slots. The theory behind cable niches is that advertisers can hit those same demographics all day, all night, all week by buying a package of channels. Because repetition is the soul of advertising, MSOs that can offer these kinds of packages find themselves in the driver’s seat of cable revenue, making it difficult for independent channels to get a share of the revenue.

Consider MSO Time Warner Cable: It has many cable programming niches in-house, including HBO, Cartoon Network, truTV, CNN, CNNfn, and Sports Illustrated. Time Warner is therefore in a position to leverage its audience clout in favor of its own new cable startups by adding those startups to a marketing package that includes many of the heavy hitters just referenced. Similarly, Viacom and Disney have vertical and horizontal integration that promotes this kind of power play.

Cable Carriage

Operators are reluctant to take on new channels—known as carriage—unless they provide access to a brand-new audience. Remember, it’s all about how the channels can pull in additional advertisers/audiences or help keep the existing. It usually takes a new channel about 36 months to reach breakeven (where income equals cost of operation). When Fox News was launched, the Murdoch-owned channel wanted to get carriage on as many operators as possible. Instead of waiting to reach significant audience levels, Fox paid a “slotting” or “carriage” fee to gain entrance. Though the early cable dream might have included easier access to the airwaves for startups, the realities are the same as in any other business: He who has the gold gets the goods.

A serious cable subscriber in a major metropolitan market can be worth between $500 and $1000 each year he or she remains connected. This comes from a combination of monthly charges, including basic package fees, additional premium channels, and about $250 over the year for selected movies and sports events, streamed on-demand or pay-per-view.

In addition, programmers pay the operators for each subscriber they can authenticate as connected and tuned in to their channels. BET, for instance, pays about 23 cents per subscriber per month and collects about 50% of the advertising dollars that are attributable to their programming. Programmers also earn revenue by licensing their programs to other channels via syndication or international sales.

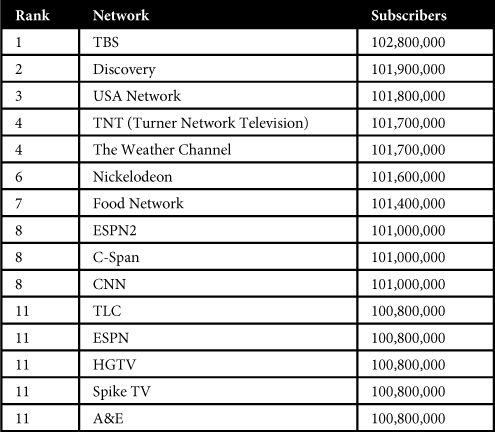

Curious as to who the top programmers are? Take a look at Exhibit 5-4.

Operators also derive income or participate on a per-inquiry basis with the television direct sales packagers of music compilations of catalog recordings or collectibles, gifts and gimmicks sold via info-commercials. Operators collect advertiser revenue on each basic channel that provides commercial airtime as well.

The most profitable carriage for an operator is the “selling up” of a subscriber to take a premium package and/or pay-per-view or on-demand programming, given the operator receives nearly 50% of the monthly fee. Because there is no advertising on these channels, the revenue split is of necessity greater than with basic channels.

However, to create revenue streams from any of these sources, a virtual maze of marketing must first take place. The cable industry must market both internally and externally, just like the networks. Cable programmers must sell their wares to cable operators as well as to viewers; cable operators must market their programs and services to their subscribers. Both must market themselves to that critical source of revenue, the advertiser.

Marketing Content: Cable Programmers

Each cable category and channel has a designated target audience. The marketing strategy for these channels is usually three-pronged:

![]() First, they must convince the viewers that the channel will provide them with exactly the information and entertainment that suits their lifestyles, their interests, their values, and their entertainment requirements.

First, they must convince the viewers that the channel will provide them with exactly the information and entertainment that suits their lifestyles, their interests, their values, and their entertainment requirements.

![]() Second, the channels must maintain a market presence with cable operators all across the U.S.—and in some cases, around the world—to ensure carriage and basic cable package support.

Second, the channels must maintain a market presence with cable operators all across the U.S.—and in some cases, around the world—to ensure carriage and basic cable package support.

![]() Third, in anticipation of each programming and advertising planning season, they must convince current and prospective advertisers and their ad agencies that they can deliver viewers of the greatest value to this business community.

Third, in anticipation of each programming and advertising planning season, they must convince current and prospective advertisers and their ad agencies that they can deliver viewers of the greatest value to this business community.

Cable channel sales and marketing professionals must support their ability to attract the customers of greatest demographic appeal to the advertisers, providing customer viewer profiles developed through proprietary or omnibus research.

The efforts of the programmers to reach their specific targets—viewers and advertisers—flow into the greater stream of the conduit itself, the cable operators. The operators provide the mass reach that allows for niche marketing, which is the heart and soul of cable.

Conduit Marketing: Cable Operators

Because cable TV, unlike network TV, is a service to which one must subscribe, it is at some level directly marketed, whether by a salesperson or through an individual’s contact with one of the nation’s nearly 12,000 local service providers—the operators. These operators target new subscribers, existing subscribers, and advertisers. Many of these 12,000 providers are owned by MSOs such as Time Warner, Comcast, Cox Communications, and Cablevision. These companies possess the resources to mount slick campaigns featuring print, audio, and video media use.

In the late 1990s, this advantage became increasingly more apparent as MSOs began to build brand images, one of the best modern-day ways to increase satisfaction and product loyalty. The MSO brand images focused on reliability, customer service, and technological leadership. MSOs also developed distinctive branding techniques as well as promotional strategies that included cooperation with frequent flyer programs, fast food industries, and cross-promotions with radio and network television stations. The target of these strategies is the subscriber, both new and existing. Dealing with subscriptions means dealing with churn (or turnover). Remember that as with any marketing, it is easier and less expensive to retain an existing customer than to acquire a new one.

The Search for Subscribers

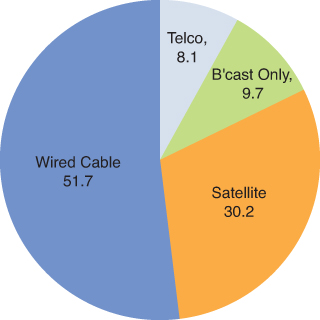

The last two decades have been the era of big cable growth. The cable industry, once populated by small-town operators and mom-and-pop stations, bought-sold-merged-acquired its way into that list of MSOs we discussed earlier. This cumulative-cable distribution—cable, satellite, and telco—now dwarfs traditional broadcasting, as demonstrated in Exhibit 5-5.

Exhibit 5-5 Television Programming Distribution 2012

Source: Nielsen, State of the Media / The Cross Platform Report 2012

Over 90% of all homes in America have easy access to cable, which means almost all households are potential cable consumers. Those not already subscribing to cable represent the greatest growth area. This includes new housing developments, apartments, and condos. Then there are those who already have access but are not currently using cable, split by cable salespeople into “nevers” and “formers.” The nevers have, as the word implies, never subscribed to cable, even though the service may be already installed in their dwelling. Formers include transient users, such as apartment dwellers.

To reach potential subscribers, the cable and satellite industries use direct marketing, banner ads, outdoor billboards, radio spots, door-to-door salespeople, and network television spots. Although TV networks and stations don’t accept advertising from direct competitors, they do willingly take the advertising dollars cable companies offer.

Small and independent cable operators that have resisted being bought out depend on their relationships within the community for marketing to their customers. Their major marketing efforts are directed at maintaining the goodwill of the customers they have, reducing churn, connecting new homeowners, and massaging the programmers who pay them for carriage of programs by selling their content.

The local operator bombards the community with coupons in local newspapers and “penny-saver,” free-circulation tabloids (sometimes owned by the local cable company), offering free installation. One of the most important aspects of his marketing program is “selling up”—marketing premium and PPV services to customers with basic cable. Bill stuffers, sent out in every monthly billing invoice, offer one month free of a premium channel or one or two free PPV movies to build trial.

The MSO uses many similar marketing tactics, with two major differences: bigger audiences in each of its locations and bigger marketing budgets. On occasion, an MSO simply unencrypts its premium channels and announces that this is its gift to loyal customers—another form of trial, without request. A certain percentage of basic cable viewers may then “convert,” purchasing the premium package. MSOs also frequently send out glossy, four-color booklets announcing upcoming movies and special programs, engaging the customer and building a “must have” sensibility.

However, MSOs have had one specific hurdle to cross in building their subscription base. The early days of cable conglomerates saw a distinct lack of service, turning off many subscribers and, in part, forcing the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, deregulating the cable industry to put pressure on the MSOs. In response, the leading cable operators focused on the service side of their business, both from the marketing and results standpoints. The results were lower churn and longer retention rates.

On the advertising side, the media company that owns the MSO can offer packages that include a cable media plan, magazines ads, radio commercials, posters at theme parks, ads on home video cassettes, and ads in cable bill enclosures. If the company owns a broadcast network, that too is factored into the package offering. Great examples of this are Comcast/NBC and Disney/ABC. Time Warner Cable/HBO used to be in that same mix, but the cable company was spun off from the parent Time Warner in 2009. Time Warner retained HBO, which it cheerfully sells to other MSOs.

There are ways for small, independent operators to gain a share of the market: the marriage of cooperation and competition known as co-opetition.

Cable Cooperatives

On occasion, a number of independent and MSO systems in a given regional territory may band together and form a marketing co-op. An example of this strategy is the Metro-Cable Marketing Co-Op, covering approximately 40 or more cable operators in the neighboring states of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. In their first joint effort, the co-op took advantage of critical mass to develop cost-effective mailing pieces offering a package of specials during one or two annual marketing periods. Potential subscribers were called to action with a 1-800-OKCable phone number.

Funding for this offer came from the combined pool of independents and MSOs. Though the average yearly budget for an individual operator might be as low as $10,000 for a small mom-and-pop and as high as $200,000 for a larger system or MSO affiliate, the co-op budget initially totaled over $1 million. This pool was matched by the programmers, with funds and film footage. The combined budget then grew to over $2 million.

The 1-800-OKCable calls were fielded by one bank of telemarketing personnel, who received the calls and dispensed the orders to the appropriate members. The marketing effort was totally accountable, measuring both cost per inquiry and cost per actual subscriber.

In the first three years, the co-op membership saw year-over-year growth of 15% in basic cable subscribers, and some systems added nearly 20% in premium and PPV revenue. The marketing budget has since grown to over $5 million. This case was reviewed at the annual Cable Tactical and Marketing (CTAM) conference; many of the strategies and marketing materials were acquired for use in other regional co-op markets.

Cable Television: A Marketing Powerhouse

Let’s take a moment to review the key attributes of cable television:

![]() Because the cable industry is both local and highly targeted, the advertiser can reach the smallest demographic, even psychographic cohort, finding like-minded folks who love history, biography, opera, sports—a seemingly endless palette of prospects.

Because the cable industry is both local and highly targeted, the advertiser can reach the smallest demographic, even psychographic cohort, finding like-minded folks who love history, biography, opera, sports—a seemingly endless palette of prospects.

![]() Metrics prove that cable viewers are loyalists, maintaining monthly subscriptions and operator revenue.

Metrics prove that cable viewers are loyalists, maintaining monthly subscriptions and operator revenue.

![]() Unlike broadcast television—which has only a general idea of who is reached—cable operators have supporting information on every single cable household, right down to payment method.

Unlike broadcast television—which has only a general idea of who is reached—cable operators have supporting information on every single cable household, right down to payment method.

![]() With the ability to match channels with customers and advertisers at far lower cost-per-thousand impressions (CPMs), it is a still a boom time for the cable industry.

With the ability to match channels with customers and advertisers at far lower cost-per-thousand impressions (CPMs), it is a still a boom time for the cable industry.

![]() Cable’s infrastructure is in place, leaving more funds for original programming, a huge drawing card for consumers. The attendant marketing by each cable network creates symbiotic marketing advantages for cable as a whole.

Cable’s infrastructure is in place, leaving more funds for original programming, a huge drawing card for consumers. The attendant marketing by each cable network creates symbiotic marketing advantages for cable as a whole.

But new technologies are threatening this business model. In a moment, the rest of the story.

Summary

As with other entertainment media, multichannel marketing executives in cable and the newer technology, satellite TV, are continuing to explore ways to reach further into the discretionary time and disposable income of today’s marketplace. Although their content beginnings played off the success of old stand-by movies, today’s multichannel media boasts some of the best original content on the airwaves, driving both advertising and subscription revenue, and challenging programmers to continue pushing the envelope.

For Further Reading

Galland, Tom, Dump Cable TV: Cut the Cord and Get the Most for Your Entertainment, TG Digital Services, 2012.

Hofer, Stephen F., and Michael Davis, TV Guide The Official Collectors Guide: Celebrating An Icon, Bangzoom Pub., 2006.

Palmer, Shelly, Television Disrupted: The Transition from Network to Networked TV, Focal Press, 2008.

Tarvin, Neil, Cutting the Cable TV Cord for Non-Geeks, 2012.