10. Financial Reporting and External Audit

In this chapter, we examine the process by which the board of directors assesses the integrity of published financial statements. As discussed in previous chapters, the accuracy of financial reporting is important for several reasons. First, this information is critical for the general efficiency of capital markets and the proper valuation of a company’s publicly traded securities. Second, an informed evaluation of a company’s strategy, business model, and risk level depends on the accurate reporting of financial and operating measures. This is true for both internally and externally reported data. Third, the board of directors awards performance-based compensation to management based on the achievement of predetermined financial targets. Accurate financial reporting is critical to ensuring that results are stated honestly and that management has not manipulated results for personal gain.

The audit committee must ensure that the financial reporting process is carried out appropriately. The committee does so in two ways: first, by working with management to set the parameters for accounting quality, transparency, and internal controls; and, second, by retaining an external auditor to test the financial statements for material misstatement.

In this chapter, we discuss both of these responsibilities. We start by considering the general obligation of the audit committee to oversee the financial reporting and disclosure process. What actions should the committee take to ensure that financial data is reported accurately? How can it decrease the likelihood of material misstatement or manipulation by management? How effective are these efforts?

Next, we evaluate the role of the external auditor. What is the purpose of an external audit? What is it expected to accomplish, and what is it not expected to accomplish? We then consider the impact that various factors have on audit quality, including the structure of the industry itself, the reliance on audit firms for nonaudit-related services, auditor independence, auditor rotation, and the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002.

The Audit Committee

The audit committee has a broad range of responsibilities. These include the responsibility to oversee financial reporting and disclosure, to monitor the choice of accounting principles, to hire and monitor the work of the external auditor, to oversee the internal audit function, to oversee regulatory compliance within the company, and to monitor risk.

Many of these responsibilities are mandated by securities regulation or federal law. For example, the audit committee’s oversight of the external audit is required by the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002. Sarbanes–Oxley also mandates that the audit committee establish procedures for receiving and handling complaints about the company’s accounting, internal controls, or auditing matters (including anonymous submissions by employees). By contrast, other responsibilities are not mandated by law but instead have evolved from historical practice. For example, the assignment of enterprise risk management to the audit committee is not a legal requirement but is an election that many companies make of their own volition.1

To ensure that the work of the committee is carried out free from the influence of management, the audit committee must consist entirely of independent directors. In addition, listing exchanges require that all members of the audit committee be financially literate and that at least one committee member qualify as a financial expert. A financial expert is defined as follows:

[Someone who] has past employment experience in finance or accounting, requisite professional certification in accounting, or any other comparable experience or background which results in the individual’s financial sophistication, including being or having been chief executive officer, chief financial officer, or other senior officer with financial oversight responsibilities.2

The audit committee can retain external advisors or consultants as it deems necessary to assist in the fulfillment of its duties, with the cost borne by the company.

Accounting Quality, Transparency, and Controls

The work of the audit committee begins with establishing guidelines that dictate the quality of accounting used in the firm. Accounting quality is generally defined as the degree to which accounting figures precisely reflect the company’s change in financial position, earnings, and cash flow during a reporting period.3

An outside observer might think that accounting quality should not be discretionary, but the nature of accounting standards somewhat requires that it be so. This is because oversight bodies—including the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the United States and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) abroad—sometimes afford considerable flexibility to companies in the manner in which they interpret and apply accounting standards. They do so to allow for the fact that it is not always clear how transactions should be valued or when the costs and revenues associated with a transaction should be recognized. In many cases, these are subject to interpretation. For example, how should a company allocate the costs associated with completing a multiyear project? Should it be evenly over the life of the project, at the time of delivery, or in some other manner that takes into account the work performed during each reporting period? Correspondingly, should the company be aggressive or conservative in recognition of the associated revenues? The way a company answers these questions has a direct impact on accounting results.

In addition, the audit committee must establish the company’s standards for transparency. Transparency is the degree to which the company provides details that supplement and explain accounts, items, and events reported in its financial statements and other public filings. Transparency is important for shareholders to properly understand the company’s strategy, operations, risk, and performance of management. It is also necessary when shareholders make decisions about the value of company securities. As such, transparent disclosure plays a key role in the efficient functioning of capital markets.

On the other hand, transparency brings risks. When a company is highly transparent, it might inadvertently divulge confidential or proprietary information that puts it at a disadvantage relative to competitors. For example, competitors might be able to use information disclosed about a company’s strategy (including the timing of a new product launch, distribution channels, pricing, marketing, and other promotion) to effectively dampen its success. Too much transparency might also weaken the bargaining position of a company. For example, counterparties could use disclosure about a company’s potential exposure to litigation to gain leverage and extract additional concessions. For these reasons, the audit committee and the entire board of directors must weigh the costs and benefits of transparency when establishing guidelines for reporting and disclosure.

Finally, the audit committee is responsible for monitoring the internal controls of the corporation. Under Section 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, management is required to assess the internal controls of the company, and the external auditor is required to attest to management’s assessment. Internal controls are the processes and procedures that a company puts in place to ensure that account balances are accurately recorded, financial statements reliably produced, and assets adequately protected from loss or theft. Effectively, internal controls act as the “cash register” of the corporation, a system that confirms that the level of assets inside the company is consistent with the level that should be there, given revenue and disbursement data recorded through the accounting system.

The audit committee determines the rigor of controls necessary to ensure the integrity of financial statements. A rigorous system is important for protecting against theft, tampering, and manipulation by management or other employees. It is also important for detecting potential regulatory violations or illegal activity, such as the payment of bribes, which are illegal under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977.4 Rigorous controls help ensure that employees do not make inappropriate adjustments to company accounts to create falsified results. If the company is too zealous in its internal controls, however, the results can be detrimental. Excessive controls can lead to bureaucracy, lost productivity, inefficient decision making, and an inhospitable work environment. As a result, the audit committee must strike a balance between proper controls that prevent inappropriate behavior and excessive controls that impact firm performance.

Survey data suggests that audit committees are confident in their ability to carry out these responsibilities. According to a study conducted by KPMG and the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD), the vast majority of audit committee members believe they are effective or very effective in overseeing management’s use of accounting (90 percent), company disclosure practices (93 percent), and internal controls (87 percent). The majority also believe they are effective in overseeing both the internal and external audit function (89 percent and 94 percent, respectively).5

Financial Reporting Quality

Several control mechanisms are in place to assist the audit committee in ensuring the integrity of financial statements. Companies hire an external auditor to test financials for material misstatement based on prevailing accounting rules. The external auditor reports its findings directly to the audit committee to ensure that the audit process has not been compromised by management influence. Companies also employ an internal audit department, which is responsible for separately testing accounting processes and controls. Under Sarbanes–Oxley, management is required to certify that financial reports do not contain misleading information. Companies that violate accounting regulations face the risk of lawsuits from shareholders and regulators. Penalties for violation include fines and, in some cases, bans from serving as an officer of a publicly traded company or even prison time for corporate officers (see the following sidebar).

Audit committee members are confident that accounting controls are effective. According to the KPMG survey cited, 89 percent of audit committee members are confident or very confident that the company’s internal audit department would report controversial issues involving senior management. Eighty-six percent are satisfied with the support and expertise they receive from the external auditor.8

Still, considerable empirical evidence suggests that accounting controls might not be as effective as audit committee members believe. For example, Dichev, Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal (2013) conducted a survey of 169 chief financial officers and found that in any given period, about 20 percent of firms manipulate earnings to misrepresent economic performance; the average level of earnings manipulation among these firms is 10 percent. This suggests that management might regularly sidestep internal controls to meet earnings targets.9 Other studies support this conclusion. For example, Burgstahler and Dichev (1997) found that companies are much less likely to report a small decrease in earnings than a small increase in earnings, even though statistically the distribution between the two should be equal.10 Carslaw (1988) examined the pattern that occurs in the second-from-left digit of net income figures. He found that zeros are overrepresented and nines are underrepresented, suggesting that companies round up their earnings to convey slightly better results.11 Similarly, Malenko and Grundfest (2014) examined the pattern that occurs when earnings per share figures are extended by one digit to include tenths of a penny. If no manipulation is occurring, fours should occur in the tenth-of-a-penny digit just as often as other numbers. Instead, the authors found that fours are significantly underrepresented, suggesting that managers manipulate results when possible so that they can report EPS figures that are one penny higher. The authors identified inventory valuation, asset writedowns, accruals, and reserves as areas that are particularly susceptible to manipulation.12

Although such behavior might allow management to meet short-term targets, it is generally detrimental to the corporation and provides some insight into the governance quality of the firm. Bhojraj, Hribar, Picconi, and McInnis (2009) found that companies that just beat earnings expectations with low-quality earnings have superior short-term stock price performance compared to companies that just miss earnings expectations with high-quality earnings. However, over the subsequent three-year period, these companies tend to underperform. The authors saw this as evidence that managers make “myopic short-term decisions to beat analysts’ earnings forecasts at the expense of long-term performance.”13 Kraft, Vashishtha, and Venkatachalam (2015) found that more frequent financial reporting (quarterly versus annual) is associated with an economically large decline in corporate investment in fixed assets. They also concluded that their results are “suggestive of myopic managerial behavior.”14 Perhaps to discourage myopic behavior among management, some companies have implemented policies that they will not issue quarterly earnings guidance. Examples include AT&T, ExxonMobil, Ford, and Walt Disney.

Financial Restatements

A financial restatement occurs when a material error is discovered in a company’s previously published financials. When such an error is discovered, the company is required to file a Form 8-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) within four days. Form 8-K alerts investors that previously published financials can no longer be relied upon and are under review for restatement. If an error is not material, the financial statements are simply amended.

According to data from the Center for Audit Quality, between 700 and 1,700 restatements occur each year. Of these, approximately 15 percent are issued by foreign companies listed in the United States. In recent years, both the number and percentage of serious restatements (that is, those reported on Form 8-K) has declined. In 2006, approximately half (53 percent) of 1,784 restatements were serious; in 2012, only 35 percent of 738 restatements were serious. Of note, the number of restatements did not increase—and in fact steadily decreased—in the five years during and after the financial crisis of 2008. This suggests that, unlike with the accounting scandals in the late 1990s that precipitated the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002, widespread accounting manipulation did not appear to play a significant role in the financial crisis of 2008.15

The most frequent causes of a restatement include improper expense recognition relating to accruals and reserve estimates (30 percent), errors related to accounting for debt and equity financing (23 percent), improper revenue recognition (14 percent), errors related to accounting for fixed assets and intangibles (13 percent), improper expense recognition related to stock-based compensation (13 percent), and tax accounting errors (11 percent). (See Table 10.1.) When a restatement results in a reduction in net income, the median reduction is 15 percent.16

Total does not equal 100 percent because some restatements are due to more than one reporting issue.

Source: Adapted from Susan Scholz, “Financial Statement Trends in the U.S.: 2003–2012,” published by the Center for Audit Quality (2014).

Table 10.1 Reasons for Financial Restatement (2003–2012)

A restatement can be required because of human error, aggressive application of accounting standards, or fraud. The distinctions are important because they have implications on the quality of internal controls and the steps that the company must take to improve oversight. For example, consider three restatements that occurred in the 1990s and 2000s:

• In 1991, Oracle restated second- and third-quarter earnings from the previous year when it was discovered that sales had been recorded prematurely. Investment analysts blamed the incident on management pressure to meet financial targets, which, in turn, caused sales associates to book contracts before they were fully closed. The practice occurred only in these two quarters, and total fiscal year results were unaffected by the timing shift.

• Between 1999 and 2001, Bristol-Myers Squibb used financial incentives to persuade wholesalers to purchase larger quantities of its drugs than needed. The company eventually reduced reported revenues by $2.5 billion because of so-called “channel stuffing” and paid fines.

• Between 1998 and 2000, the CEO and other senior executives of Computer Associates engaged in a systematic process of backdating customer contracts and altering sales documents to move revenue into earlier periods. When questioned about their actions, they lied to internal investigators, the SEC, and the FBI. Those involved went to prison—including the CEO, who was sentenced to a 12-year term.

The actions at Oracle and Bristol-Myers were due to aggressive behavior on the part of management and required a change in incentives and more effective internal controls. The actions at Computer Associates, however, were clearly fraudulent and stemmed from an ethical breakdown that pervaded the entire organization. As a result, it required a much more extensive overhaul of the governance system, including a complete change in senior leadership, dismissal of the external auditor, and fairly substantial turnover among board members.

The evidence indicates that investors differentiate between more and less egregious forms of manipulation. According to the Center for Audit Quality, companies that announce serious restatements exhibit a 2.3 percent decrease in stock price in the two days following the announcement, compared with a 0.6 percent decrease for companies announcing a nonserious restatement. Stock price performance tends to be the worst when the restatement is caused by improper revenue recognition.17

Similarly, Palmrose, Richardson, and Scholz (2004) found that companies exhibit a 9 percent average (5 percent median) decrease in stock price in the two days following a restatement announcement. Reaction is more negative when the restatement is due to fraud (–20 percent), was initiated by the external auditor (–18 percent), or reflects a material reduction in the company’s previous earnings (–14 percent). The authors hypothesized that “the negative signal associated with fraud and auditor-initiated restatements is associated with an increase in investors’ expected monitoring costs, while higher materiality is associated with greater revisions of future performance expectations” (see the following sidebar).18

Badertscher, Hribar, and Jenkins (2011) found that the stock price reaction to a restatement is significantly less negative when managers are net purchasers of the stock before the restatement and significantly more negative when managers are net sellers. These results suggest that investors rely on informed insider trading activity as a potential clue to the likely severity of a restatement.19

Financial restatements tend to have a negative impact on companies well beyond the announcement date. Karpoff, Lee, and Martin (2008) found that companies that issue material restatements continue to trade at lower valuations even after adjusting for reductions in book value and earnings that result from the restatement.22 Amel-Zadeh and Zhang (2015) found that firms that file a restatement are significantly less likely to become takeover targets and that those that do receive takeover bids take longer to complete or are more likely to have the bids withdrawn. They also found some evidence that deal value multiples are lower for restating firms than for non-restating firms.23 Research evidence exists that firms that issue a financial restatement are more likely to be sued and suffer other negative repercussions, such as higher management turnover.24

Some evidence indicates that financial restatements are correlated with weak governance and regulatory controls. For example, Beasley (1996) found that companies with a lower percentage of outside directors are more likely to be the subject of financial reporting fraud. He also found that other governance features—low director ownership of company stock, low director tenure on the board, and busy board members—are correlated with fraud.25 Farber (2005) found that firms that are found to have committed fraud have fewer outside directors, fewer audit committee meetings, fewer financial experts on the audit committee, and a higher percentage of CEOs who are also chairman.26 Correia (2014) found that companies with low accounting quality spend more money on political contributions—particularly to members of Congress with strong ties to the SEC—and that these contributions are correlated with a lower likelihood of SEC enforcement action and lower penalties for firms found guilty of violations. She posited that companies at risk of financial statement fraud might use political contributions to reduce their regulatory exposure.27

However, the evidence that financial restatements are correlated with typical governance features is not conclusive. The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) reviewed fraud investigations occurring between 1998 and 2007 and found no relation to size of the board, frequency of meetings, or composition and experience of directors.28

A behavioral component likely is involved in financial reporting fraud. Magnan, Cormier, and Lapointe-Antunes (2010) argued that an exaggerated sense of self-confidence, encouraged by lavish media attention and praise, might encourage CEOs who are inclined to commit fraud to take increasingly aggressive actions without fear of detection or reproach. As they explained, “Almost all sample firms and/or their CEOs were the objects of positive media or analyst coverage in the period preceding or concurrent to the fraudulent activities. In our view, such coverage translated into a higher sense of self-confidence or invulnerability among the executives, i.e., managerial hubris. Managerial hubris either led guilty executives further down the path of deception and fraud or, alternatively, pulled their supervising executives away from efficient and effective monitoring.” They recommend that more attention be paid to behavior cues and that auditors greet the appearances of good governance with skepticism (see the next sidebar).29 Similarly, Feng, Ge, Luo, and Shevlin (2011) examined why CFOs become involved in material accounting manipulations and concluded that they do so because they succumb to pressure from CEOs rather than because of potential personal financial gain.30 Conversely, Garrett, Hoitash, and Prawitt (2014) found that organizations with high levels of intraorganizational trust have higher accounting quality, fewer misstatements, and a lower likelihood of material weaknesses in their internal controls.31

Dyck, Morse, and Zingales (2010) studied a comprehensive list of fraud cases between 1996 and 2004. They found that legal and regulatory mechanisms (such as the SEC and external auditors) and financial parties (such as equity holders, short sellers, and analysts) were less effective at detecting fraud than uninvolved third parties that are typically seen as less important players in governance systems. Employees, non-financial-market regulators, and the media were credited with uncovering 43 percent of the fraud cases, compared with 38 percent for financial parties and 17 percent for legal and regulatory agents. They offered two explanations for these findings. Employees and nonfinancial regulators might be more effective in discovering fraud because they have greater access to internal information and, therefore, lower costs of monitoring. Journalists might be effective monitors because of reputational gains.32

Models to Detect Accounting Manipulations

Researchers and professionals have put extensive effort into developing models to detect the manipulation of reported financial statements. Such tools are useful not only for auditors and the audit committee (and perhaps the board in general) but also for investors, analysts, and others who rely on credible financial reports. These efforts have been met with somewhat limited success, although in certain circumstances they have predictive ability in whether a restatement will occur.

One set of models measures accounting quality in terms of accounting accruals. Accrual accounting is based on the premise that the profitability of a corporation can be measured more accurately by recognizing revenues and expenses in the period in which they are realized than in the period in which cash is received or dispensed. Accrual accounting reduces the variability that is inherent in cash flow accounting and provides a more normalized view of earnings. Because accrual accounting relies more heavily on managerial assumption than cash flow accounting, however, it is more easily subject to manipulation. If management manipulates results over time, reported earnings will steadily diverge from cash flows. The difference between accruals and cash flows (after adjusting for the typical or normal accruals that will occur during the application of the accounting process), known as abnormal accruals, might be used as a measure of earnings quality.

Several researchers have developed models that use abnormal accruals to predict financial restatements. One widely used model was developed by Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1995), based on a modification of Jones (1991).34 Another was developed by Beneish (1999). His model uses the following metrics as inputs:

• The change in accounts receivables as a percent of sales over time

• The change in gross margin over time

• The change in noncurrent assets other than plant and equipment over time

• The change in sales over time

• The change in working capital (minus depreciation) over time, in relation to total assets

Beneish (1999) tested his model against both companies that have restated their earnings and those that have not. He found that excessive changes in these metrics have predictive power in whether a company is likely to restate earnings, and the results were statistically significant.35 However, accrual-based models such as these tend to have a very modest success rate in predicting future restatements.

GMI Ratings has also developed a model with a slightly higher success rate in predicting financial restatements. The company uses a composite metric that aggregates both accounting and governance data to identify companies at risk of restatement and other negative outcomes such as fraud, debt default, and lawsuits. The company computes Accounting and Governance Risk (AGR) scores on a scale of 0 to 100, with low ratings indicating a higher likelihood of restatement or adverse outcome. GMI Ratings claims that companies that are in the lowest decile according to its model account for 31 percent of all restatements, whereas those in the highest decile account for only 3.1 percent. In addition, it claims that “not only are the high-risk companies substantially more likely to face a restatement than the low-risk firms, but the estimated probabilities neither understate nor overstate the actual likelihood of the restatement.”36

Independent testing has confirmed that GMI Ratings’ models have some predictive power. Price, Sharp, and Wood (2011) found that AGR is more successful in detecting financial misstatements than are standard accrual-based models, such as those discussed earlier.37 Correia (2014) also found that AGR is slightly more effective (but statistically equivalent) in predicting accounting restatements than accrual-based models. Still, the precision of both models is relatively low—no more than 10 percent.38

Finally, evidence indicates that adding linguistic-based analysis can improve the predictive ability of accrual-based models. Larcker and Zakolyukina (2012) studied the Q&A section of quarterly earnings conference calls. They found that certain linguistic tendencies are associated with future restatements:

• CEOs make fewer self-references (that is, they’re less likely to use the pronoun I).

• They are more likely to use impersonal pronouns (such as anyone, nobody, and everyone).

• They make more references to general knowledge (such as “you know”).

• They express more extreme positive emotions (fantastic as opposed to good).

• They use fewer extreme negative emotions.

• They express less certainty in their language.

• They are less likely to refer to shareholder value.

The predictive ability of the model using these cues is better than chance and better than the accrual models. The authors conclude that “it is worthwhile for researchers to consider linguistic measures when attempting to measure the quality of reported financial statements.”39 However, this type of research is still in its infancy.

The External Audit

The external audit assesses the validity and reliability of publicly reported financial information. Shareholders rely on financial statements to evaluate a company’s performance and to determine the fair value of its securities. Because management is responsible for preparing this information, shareholders expect an independent third party to provide assurance that the information they receive is accurate. The external auditor serves this purpose.

The external audit process is broken down as follows:40

1. Audit preparation—The external audit is tailored to the industry, the nature of operations, and the company’s organizational structure and processes. Before the audit takes place, the auditor and the audit committee discuss and determine its scope. The auditor uses professional judgment to determine how best to perform its assessment. This involves identifying areas that require special attention, evaluating conditions under which the company produces accounting data, evaluating the reasonableness of estimates, evaluating the reasonableness of management representations, and making judgments about the appropriateness of the manner in which accounting principles are applied and the adequacy of disclosures.

2. Review of accounting estimates and disclosures—The audit is predicated on a sampling of accounts. Highest attention is paid to the accounts that are at the greatest risk of inaccuracy. These generally include the following:

• Restructuring charges

• Impairments of long-lived assets

• Investments

• Goodwill

• Depreciation and amortization

• Loss reserves

• Repurchase obligations

• Inventory reserves

• Allowances for doubtful accounts41

In determining the reasonableness of management estimates, the auditor reviews and tests the processes by which estimates are developed, calculates an independent expectation of what the estimates should be and reviews subsequent transactions or events for further comparison. The auditor also evaluates the key factors or assumptions that are significant to the estimate and the factors that are subjective and susceptible to management bias.

3. Fraud evaluation—The main objective of the audit is to test for validity and reliability. The auditor does not explicitly focus on whether errors result from inadvertent mistakes or fraudulent action, but public shareholders and many board members expect that auditors will root out fraud if it exists. Auditing standards encourage auditors to use “professional skepticism” to determine whether fraud has occurred.42 In the scope of the audit, auditors evaluate the incentives and pressures placed on management. They also review the opportunities for fraud to take place. Nevertheless, despite public conception to the contrary, it is not the explicit objective of the audit to identify fraud.43

4. Assessment of internal controls—Under Section 404 of Sarbanes–Oxley, the external auditor is required to perform an assessment of the company’s internal controls.44 The auditor assesses the design of entity-level controls, controls relating to risk management, significant accounts and their disclosure, the process for developing inputs and assumptions for management estimates, and the use of external specialists who assist in preparing estimates. To identify areas where internal controls can lead to material misstatement, the auditor pays particular attention to significant or unusual transactions, period-ending adjustments, related-party transactions, significant management estimates, and incentives that might create pressure on management to inappropriately manage financial results. In 2010, approximately 2 percent of companies received an adverse opinion from their auditors regarding their internal controls.45

5. Communication with the audit committee—The external auditor discusses its findings with the audit committee. The auditor’s communications with the committee include an assessment of the consistency of the application of accounting principles, the clarity and completeness of the financial statements, and the quality and completeness of disclosures. Particular attention is paid to changes in accounting policies, the appropriateness of estimates, unusual transactions, and the timing of significant items. The auditor reports directly to the audit committee and may also communicate and discuss its findings with the chief financial officer and other employees of the company.

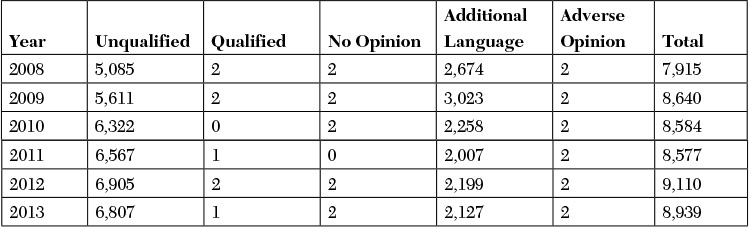

6. Expressed opinion—The ultimate objective of the audit is to express an opinion on whether the company’s financials adequately comply with regulatory accounting standards. If the auditor finds no reason for concern that the statements are materially misleading, the firm expresses an unqualified opinion that accompanies the financial statements in the annual report. (Alternatively, the auditor issues a qualified opinion and explains the reason for concern.) The unqualified opinion generally states that “the financial statements present fairly the financial condition, the results of operations, and the cash flows of the company [for specific years], in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America.” The auditor also specifies whether the company can continue to operate profitably as a going concern. Qualified, adverse, or no opinions occur very infrequently (see Table 10.2).46

Additional language might be used in an unqualified opinion to indicate an inconsistency in the application of an accounting principle, to emphasize a matter of importance, or to express concern about the company’s ability to remain a going concern. An adverse opinion means that the company’s financial statements are misstated. No opinion (or a disclaimer of opinion) means that the auditor could not complete the scope of the audit.

Source: Computed from Standard & Poor’s Compustat.

Table 10.2 Auditor Opinions (2008–2013)

In summary, the external auditor is not responsible for the presentation or accuracy of financial statements but instead reduces the risk that statements are misleading by performing a check on management and its financial reporting procedures. The board of directors and company shareholders may expect the auditor to find all material errors and instances of fraud, but given the process of the audit, that is an unrealistic expectation (see the following sidebar).

According to data from Audit Analytics, companies in the Russell 3000 spend approximately 0.1 percent of revenue on audit fees.47 Audit fees are only a portion of the total cost of ensuring the integrity of financial reporting and controls. A complete assessment would include the incremental cost of the audit committee, the internal audit department, and the fraction of time spent by the finance, accounting, and legal departments on reporting-related issues.

Audit Quality

Given the importance of the external audit, much attention has been paid to factors that might impact audit quality. These include consolidation among the major audit firms, whether conflicts exist when the auditor also provides nonaudit-related services to the client, whether conflicts exist when a member of the audit firm is hired into a senior finance role at the client, and how auditor rotations impact audit quality. We discuss these in the remainder of this chapter.

Structure of Audit Industry

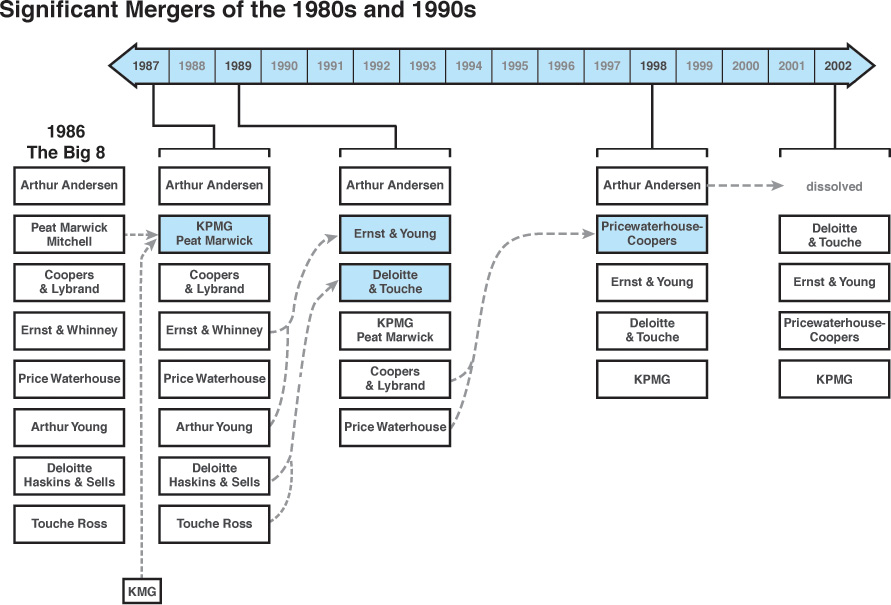

The audit industry is characterized by extreme concentration among four main firms: Deloitte & Touche, Ernst & Young, KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers. Together, these firms are known as the Big Four. The Big Four handle approximately 98 percent of the audits of large U.S. companies and earn 94 percent of total industry revenue for audit and audit-related services.55 The rest of the industry is characterized by several midsize firms, such as Grant Thornton and BDO Seidman, and thousands of boutique firms that cater primarily to local businesses.

As recently as the late 1980s, there were eight major accounting firms, but in the ensuing years, the industry has consolidated (see Figure 10.1).

In 2002, the Department of Justice indicted Arthur Andersen on obstruction of justice charges for destroying documents relating to its audit of Enron. The firm was found guilty, lost its SEC license, and was forced to dissolve. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the verdict on procedural grounds. Nevertheless, it was too late to salvage the company.

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Audits of Public Companies: Continued Concentration in Audit Market for Large Public Companies Does Not Call for Immediate Action,” GAO-08-163.

Figure 10.1 Consolidation among large accounting firms.

Several factors have contributed to concentration in the audit industry. First, scale among accounting firms is required to match the scale of international corporations. As companies expand around the globe, they require larger and more sophisticated accounting firms to resolve complex issues. These same firms are equipped to handle the complexity of an international audit. Scale is also important for the significant investment in information technology systems that are required to support a global audit. Second, because audit firms have deep expertise about their clients’ accounting systems, their clients historically have hired them for nonaudit-related services, including tax, advisory, information technology systems, and consulting services. This has contributed to the global size and reach of the largest firms. Third, auditors are subject to intense legal scrutiny. Large firms are capable of surviving large legal penalties that would bankrupt smaller competitors. For example, between 1992 and 2014, the Big Four paid a combined total of $6.2 billion in legal settlements.56

Most countries require that audit firms be owned and managed by locally licensed auditors. As a result, the Big Four are not organized as a single corporation managed by a CEO and overseen by a board of directors. Instead, the Big Four consist of a collection of affiliated firms, each of which is locally owned and operated.57 These firms benefit from the reputation and global resources of the Big Four but have the expertise of understanding country-specific regulations, accounting standards, and business practices. This structure allows them to cater to the local offices of multinational corporations and still maintain the economies of scale to make them globally competitive. It also means that, for the most part, when a Big Four firm is subject to shareholder or regulatory litigation, only the local office is named in the lawsuit.58

Much debate circulates over whether the concentration of market share among the Big Four has led to a decrease in competition and reduction in audit quality. In 2008, the GAO examined this issue and was unable to find a clear link between industry concentration and anticompetitive behavior. Still, 60 percent of the large companies that the GAO surveyed believed they did not have an adequate number of firms from which to choose their auditor. Smaller companies saw no such problem; 75 percent of them believed that the number of audit firms available to them was sufficient. Respondents also indicated that, although audit and audit-related fees have increased significantly in recent years, they did not believe that the increase in cost was due to anticompetitive behavior. Instead, they believed that it reflected the cost of compliance with stricter regulatory oversight (including Sarbanes–Oxley); the greater scope of the audit; and the cost of hiring, training, and retaining qualified professionals.

The GAO (2008) also examined the possibility of requiring the Big Four to split into smaller firms to increase competition and selection. Executives from large companies expressed concern that forced divestiture by the Big Four would reduce their expertise and decrease audit quality, although they agreed that further concentration among the Big Four might lead to insufficient choice.59

Research evidence on whether Big Four auditors provide higher-quality audits than non–Big Four auditors among similar types of firms is inconclusive. Palmrose (1988) and Khurana and Raman (2004) found positive evidence that this is the case, based on lower litigation risk.60 However, Lawrence, Minutti-Meza, and Zhang (2011) found no significant difference between Big Four and non–Big Four auditors in terms of the accounting quality and cost of equity capital of their clients.61 One limitation that researchers face in assessing the audit quality of Big Four firms is that comparisons can only be made among smaller and mid-sized companies that can reasonably be audited by either Big Four and non–Big Four firms. Comparisons cannot be made among large companies that, because of their size and complexity, can only reasonably be audited by very large audit firms.

Impact of Sarbanes–Oxley

The audit industry in the United States has historically been self-regulated. For many years, auditing standards were developed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), a national association of accountants. These standards, known as Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS), set professional and ethical guidelines for auditors. Following the scandals of Enron, WorldCom, and others in 2001 and 2002, congressional leaders made efforts to formalize auditor oversight as a step toward improving investor confidence in published financial statements.

Therefore, the U.S. government passed the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). Among its provisions, Sarbanes–Oxley established the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to regulate the audit industry. Prior to Sarbanes–Oxley, audit firms were subject to a peer review every three years, in which outside accountants tested the firm’s compliance with quality-control systems for both accounting and audit. The peer review system was seen as deficient because it relied on industry self-policing and because the review was limited to testing control systems and did not examine the full scope of the audit firm’s activities.62 This system was replaced by one in which auditors are required to register with a public regulator (PCAOB), which inspects large audit firms every year and small audit firms every three years. PCAOB inspections differ from the peer review process in that they:

• Are structured around a risk-based inspection (the audits subject to review are those seen as having the highest likelihood of a material omission or misstatement)

• Are given broad latitude to inspect any audit firm activity that might violate auditing standards or SOX

• Examine the “tone from the top” (attitude of the firm’s management toward regulatory compliance)63

The PCAOB has the power to impose disciplinary measures when violations are detected. In addition to its inspection and enforcement powers, the PCAOB proposes auditing standards. Following passage of SOX, the PCAOB adopted the auditing standards of the AICPA while it drafted its own standards.64

Sarbanes–Oxley also enacted measures to reduce potential conflicts of interest between auditors and their clients. Section 201 of the law prohibits auditors from performing certain nonaudit services for their audit clients, including bookkeeping, financial information system design, fairness opinions, and other appraisal and actuarial work. These measures are intended to increase the independence of the external auditor by encouraging the auditor to stand up to management without fear of recourse that would result from losing a lucrative consulting relationship.

A number of studies have examined the impact of Sarbanes–Oxley or features restricted by SOX on audit quality. Interestingly, most of the research suggests that SOX restrictions on nonaudit-related service are not shown to improve audit quality. Romano (2005) provided a comprehensive review of the research literature and came to this conclusion. In the studies she reviewed, audit quality was measured in a variety of ways, including abnormal accruals, earnings conservatism, failure to issue qualified opinions, and financial restatements. She interpreted these results as indicating that marketplace factors (such as concern for reputation and competition for clients) deterred auditors from abusing their position to gain auxiliary revenue from nonaudit services.65

Romano (2005) also found that the U.S. Congress, in debating Section 201 of SOX, had ignored most of the research literature. Only one study was cited in congressional debate, and it was one that had already been largely disproven at the time.66 None of the contravening evidence was considered, even though it was well understood by academics and professionals. Romano blamed this willful ignorance on a rush to respond to the collapse of Enron, a declining stock market, and upcoming midterm elections that compelled politicians to pass an important piece of legislation without “the healthy ventilation of issues that occurs in the usual give-and-take negotiations.” She concluded that because the evidence does not support their effectiveness, the “corporate governance provisions of SOX should be stripped of their mandatory force and rendered optional for registrants.”67

This is not to say that Sarbanes–Oxley has been negative. In many ways, the legislation has focused the efforts of many constituents—including external auditors, internal auditors, audit committee members, managers, and shareholders—on practical methods to improve financial statement quality.

Still, these changes have come at a considerable cost. According to Audit Analytics, audit costs almost doubled among the 3,000 companies that came into compliance with SOX in the two years following enactment.68 Furthermore, the amount of the increase was substantially higher than expected. Maher and Weiss (2010) found that the median cost of compliance with new provisions of SOX was between $1.3 million and $3.0 million annually in the four years following enactment. This compares with an original estimate of $91,000 by the SEC.69 The largest increase in audit costs has been incurred by financial institutions, due to the complexity of their audits and internal controls. In addition, smaller companies have incurred higher costs (relative to revenues) than larger companies because of the considerable fixed-cost portion of an external audit. A survey by Grant Thornton found that the increased cost of regulatory compliance is a top concern among internal audit departments.70

More than a decade after the enactment of Sarbanes–Oxley, its cost–benefit implications remain unclear. Based on a survey of 2,901 corporate insiders, Alexander, Bauguess, Bernile, Lee, and Marietta-Westberg (2013) found that 80 percent of respondents ascribe some benefits to the Act. These benefits include positive impact on firms’ internal controls (73 percent), audit committee confidence in internal controls (71 percent), improved financial reporting quality (48 percent), and ability to prevent and detect fraud (47 percent). Still, the majority of companies believe that the benefits do not outweigh the costs of compliance.71

Coates and Srinivasan (2014) conducted a comprehensive review of the research on the Act’s impact. They found that the quality of financial reporting improved following enactment and that the cost of compliance has steadily decreased following an initial spike; however, they found that the direct costs continue to fall disproportionately on small firms. They also noted several indirect costs, such as decreased listings of small firms in public equity markets and a decline in corporate investment, but they could not accurately measure the size of these costs or induce causality from Sarbanes–Oxley. They concluded that the cost–benefit trade-off is unclear.72

External Auditor as CFO

A company might find it beneficial to offer a job to a member of the external auditing team, in either the finance, treasury, internal audit, or risk management departments. Hiring a former auditor has several advantages. These individuals are familiar with the company’s business, internal practices, and procedures. They know (and presumably have good working relations with) other members of the staff. The company has had the opportunity to witness their working style, knowledge, and expertise firsthand. Therefore, hiring a former auditor allows a company to benefit from lower training costs and more reliable cultural fit.

Hiring a former auditor also has potential drawbacks. These individuals might feel an allegiance to their former employer and, therefore, be less willing to challenge their work. In addition, a former auditor has intimate knowledge of the company’s internal control procedures and would be more adept at maneuvering around them without detection. As such, the company might find itself more greatly exposed to fraud. To address these concerns, Sarbanes–Oxley requires that former auditors undergo a one-year “cooling-off” period before they can accept an offer to work for a former client.

Some research evidence shows that audit quality suffers when a company hires a former auditor. Dowdell and Krishnan (2004) found that companies that hire a former auditor as their new CFO tend to exhibit a decrease in earnings quality. In addition, the authors found that a cooling-off period did not improve earnings quality. Observed decreases in earnings quality were not materially different whether the employee was hired more than or less than one year after leaving the audit firm.73

Other studies did not find significant evidence that hiring a former audit team member leads to a decrease in earnings quality. Geiger, North, and O’Connell (2005) examined a sample of more than 1,100 executives who were hired into a financial reporting position (CFO, controller, vice president of finance, or chief accounting officer) between 1989 and 1999. Of this group, 10 percent were hired from the company’s current external audit firm. The authors compared the earnings quality of this group against three control groups: (1) executives who had not worked as an auditor immediately before being hired by the company, (2) executives who had worked for an audit firm that was not the company’s current auditor prior to being hired, and (3) companies that had not made a new hire and instead retained their existing financial executives. They found no evidence that the source of hire had an impact on earnings quality. The authors concluded that even though “several recent highly publicized company failures have involved [so-called] ‘revolving door’ hires . . . there does not appear to be a pervasive problem regarding excessive earnings management associated with this hiring practice.”74

That is, even though hiring a former auditor as a financial officer might carry potential risks (as at HealthSouth), the evidence is weak that such a practice routinely compromises audit quality.

Auditor Rotation

Proposals have also been made that companies be required to rotate the external auditor periodically to ensure its independence and decrease the risk of fraud. Advocates of this approach argue that, over time, audit firms grow stale in their review of the same accounts and that a new audit firm brings fresh perspective to company procedures. Furthermore, they argue that members of the audit team develop personal relationships with company employees, further reducing their independence. Rotating the audit firm or the lead engagement partner is intended to counteract these tendencies. Critics of auditor rotation contend that it is overly costly to change audit firms or lead engagement partners because the new audit team must learn company policies and procedures from scratch. This can be time-consuming and can reduce audit quality while the new firm is going up the learning curve.

Regulators in many countries tend to view auditor rotation favorably. For example, Sarbanes–Oxley requires that audit firms rotate the lead engagement partner on all public company audits every five years.75 The law stopped short of requiring that companies rotate their audit firm on a fixed schedule. Other countries have such regulations, however. For example, Italy, Brazil, and South Korea require audit firm rotation for all publicly traded companies. In India and Singapore, mandatory rotation is required only for domestic banks and certain insurance companies. Australia, Spain, and Canada previously required audit rotation but ultimately dropped the requirement.

The empirical evidence indicates that auditor rotation most likely does not improve audit quality. Cameran, Merlotti, and Di Vincenzo (2005) reviewed 26 regulatory reports and 25 empirically based academic studies on auditor rotation.76 Only 4 of the regulatory reports concluded that auditor rotation is favorable; the rest determined that the costs of rotation outweighed its benefits. For example, the Association of British Insurers (ABI), American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), European Federation of Accountants and Auditors (EFAA), Fédération des Experts Comptables Européens (FEE), Institut der Wirtschaftsprüfer (IDW), and U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) all found that mandatory auditor rotation is not cost-effective. Similarly, 19 of the 25 empirically based academic studies did not support mandatory rotation.77

Of course, some companies change auditors through the normal course of business.78 The company might have grown to such a size or level of sophistication that it requires an auditor with greater expertise or geographical reach. The company might also simply be dissatisfied with the auditor’s services or fees. When the company decides to replace its auditor, it is known as a dismissal. Dismissals can be concerning to investors because they might indicate that the company is seeking more lenient treatment of its accounting and controls procedures (opinion shopping). Alternatively, the auditor can resign from a client account. In this case, it is considered a resignation. Auditor resignations are potentially more troublesome for investors than dismissals in that they are more likely to indicate a disagreement over the application of accounting principles, company disclosure, or material weaknesses in the company’s internal controls. Given the auditor’s exposure to potential liability from a financial misstatement or fraud, the auditor might decide that it is easier to resign from an account than to continue to negotiate with management over accounting changes. Still, both a dismissal and a resignation can indicate deterioration in governance oversight.

Auditor changes must be disclosed to investors through a Form 8-K filing with the SEC. In the filing, the company outlines that a change in auditor has taken place and the reason for that change. The audit firm is required to report whether it agrees or disagrees with the company’s explanation. The auditor must also report any concern about the reliability of the company’s internal controls or financial statements.79

As we might expect, the market reacts negatively to auditor resignations. Shu (2000) found that a company’s stock price significantly underperforms the market around the announcement of an auditor resignation but does not underperform following dismissals. She interpreted these results as indicating that investors react negatively to audit resignations because of their implication for future earnings or financial restatement risk.80 Whisenant, Sankaraguruswamy, and Raghunandan (2003) reported similar findings. They found that the market reacts negatively when the auditor’s resignation calls into question the reliability of financial statements but not when it suggests that the company might have insufficient internal controls. They speculated that auditor resignations due to a disagreement over the reliability of financial statements signals an “early warning” of accounting trouble to market participants, whereas a disagreement over insufficient internal controls is too imprecise for the market to react to.81

Endnotes

1. Under Sarbanes–Oxley, the audit committee is required to oversee the risks associated with internal controls and the preparation of financial statements but not to oversee enterprise risk management, as defined in Chapter 6, “Strategy, Performance Measurement, and Risk Management.”

2. NASDAQ, “NASDAQ Rule Filings: Listed Companies—2002, SR NASD 2002 141.” Accessed April 20, 2015. See http://www.nasdaq.com/about/RuleFilingsListings/Filings_Listing.stm.

3. Considerable disagreement exists among academics regarding how to measure accounting quality. Dechow and Schrand (2004) measured earnings quality in terms of the precision with which business operating performance is reported. This approach is consistent with a view that large noncash accruals denote low-quality earnings, in that earnings diverge from reported cash flows. Francis, Schipper, and Vincent (2003) measured earnings quality in terms of the precision with which the change in corporate value is reported. This view prescribes that the earnings should reflect the change in the market value of the balance sheet during a reporting period. The American Accounting Association (2002) takes a holistic assessment of earnings quality, including operating results; balance sheet valuation; earnings management; and the perspectives of external auditors, analysts, and international organizations. See Patricia M. Dechow and Catherine M. Schrand, “Earnings Quality,” Research Foundation of CFA Institute (2004); Jennifer Francis, Katherine Schipper, and Linda Vincent, “The Relative and Incremental Explanatory Power of Earnings and Alternative (to Earnings) Performance Measures for Returns,” Contemporary Accounting Research 20 (2003): 121–164; The Accounting Review Conference (January 24–26, 2002); and a special issue of The Accounting Review (Volume 77, Supplement 2002), edited by Katherine Schipper.

4. See David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan, “Baker Hughes: Foreign Corrupt Practices Act,” Stanford GSB Case No. CG-18 (August 31, 2010).

5. Audit Committee Institute, “The Audit Committee Journey. Recalibrating for the New Normal. 2009 Public Company Audit Committee Member Survey,” KPMG (2009). Accessed November 11, 2010. See www.kpmginstitutes.com/insights/2009/highlights-5th-annual-issues-conference.aspx.

6. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “2014 Annual Report to Congress on the Dodd–Frank Whistleblower Program” (November 17, 2014). Accessed April 17, 2015. See http://www.sec.gov/about/offices/owb/annual-report-2014.pdf.

7. Christina Rexrode and Timothy W. Martin, “Whistleblowers Score a Big Payday,” Wall Street Journal Online (December 19, 2014). Accessed April 17, 2015. See http://www.wsj.com/articles/third-whistleblower-to-collect-reward-related-to-bank-of-america-settlement-1419014474.

8. Audit Committee Institute (2009).

9. Ilia D. Dichev, John R. Graham, Campbell R. Harvey, and Shivaram Rajgopal, “Earnings Quality: Evidence from the Field,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2013): 1–33.

10. David Burgstahler and Ilia Dichev, “Earnings Management to Avoid Earnings Decreases and Losses,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1997): 99–126.

11. Charles A. P. N. Carslaw, “Anomalies in Income Numbers: Evidence of Goal-Oriented Behavior,” The Accounting Review 63 (1988): 321–327.

12. Nadya Malenko and Joseph Grundfest, “Quadrophobia: Strategic Rounding of EPS Data,” Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper No. 65; Stanford Law and Economics Olin Working Paper No. 388, Social Science Research Network (July 2014). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1474668.

13. Sanjeev Bhojraj, Paul Hribar, Marc Picconi, and John McInnis, “Making Sense of Cents: An Examination of Firms That Marginally Miss or Beat Analyst Forecasts,” Journal of Finance 64 (2009): 2361–2388.

14. Arthur G. Kraft, Rahul Vashishtha, and Mohan Venkatachalam, “Real Effects of Frequent Financial Reporting,” Social Science Research Network (January 8, 2015). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2456765.

15. Susan Scholz, “Financial Statement Trends in the U.S.: 2003–2012,” Center for Audit Quality (2014).

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Zoe-Vonna Palmrose, Vernon J. Richardson, and Susan Scholz, “Determinants of Market Reactions to Restatement Announcements,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 37 (2004): 59.

19. Brad A. Badertscher. Paul Hribar, and Nicole Thorne Jenkins, “Informed Trading and the Market Reaction to Accounting Restatements,” Accounting Review 86 (2011): 1519–1547.

20. The information in this sidebar is adapted with permission from Madhav Rajan and Brian Tayan, “Financial Restatements: Methods Companies Use to Distort Financial Performance,” Stanford GSB Case No. A-198 (June 10, 2008). See Krispy Kreme Doughnuts, Forms 8-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission July 30, 2004; October 10, 2004; January 4, 2005; and August 10, 2005.

21. Krispy Kreme Doughnuts, Form 10-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission October 31, 2006; and Form DEF 14A, filed April 14, 2004, and April 28, 2006.

22. Jonathan M. Karpoff, D. Scott Lee, and Gerald S, Martin, “The Cost to Firms of Cooking the Books,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 43 (2008): 581–611.

23. Amir Amel-Zadeh and Yuan Zhang, “The Economic Consequences of Financial Restatements: Evidence from the Market for Corporate Control,” Accounting Review 90 (2015): 1–29.

24. Daniel Bradley, Brandon N. Cline, and Qin Lian, “Class Action Lawsuits and Executive Stock Option Exercise,” Journal of Corporate Finance 27 (2014): 157–172; also see Hemang Desai, Chris E. Hogan, and Michael S. Wilkins, “The Reputational Penalty for Aggressive Accounting: Earnings Restatements and Management Turnover,” The Accounting Review 81 (2006): 83–112.

25. Mark S. Beasley, “An Empirical Analysis of the Relation between the Board of Director Composition and Financial Statement Fraud,” Accounting Review 7 (1996): 443–465.

26. David B. Farber, “Restoring Trust after Fraud: Does Corporate Governance Matter?” Accounting Review 80 (2005): 539–561.

27. Maria M. Correia, “Political Connections and SEC Enforcement,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 57 (2014): 241–262.

28. Mark S. Beasley, Joseph V. Carcello, Dana R. Hermanson, and Terry L. Neal, “Fraudulent Financial Reporting 1998–2007: An Analysis of U.S. Public Companies,” Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commissions (May 2010). Accessed November 13, 2010. See www.coso.org/documents/cosofraudstudy2010.pdf.

29. Michel Magnan, Denis Cormier, and Pascale Lapointe-Antunes, “Like Moths Attracted to Flames: Managerial Hubris and Financial Reporting Fraud,” CAAA Annual Conference 2010, Social Science Research Network (2010). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1531786.

30. Mei Feng, Weili Ge, Shuqing Luo, and Terry Shevlin, “Why Do CFOs Become Involved in Material Accounting Manipulations?” Journal of Accounting and Economics 51 (2011): 21–36.

31. Jace Garrett, Rani Hoitash, and Douglas F. Prawitt, “Trust and Financial Reporting Quality,” Journal of Accounting Research 52 (2014): 1087–1125.

32. Alexander Dyck, Adair Morse, and Luigi Zingales, “Who Blows the Whistle on Corporate Fraud?” Journal of Finance 65 (2010): 2213–2253.

33. Paraphrased SEC Commissioner James C. Treadway remarks made to the American Society of Corporate Secretaries, Inc., in Cleveland, Ohio, on April 13, 1983, titled “Are ‘Cooked Books’ a Failure of Corporate Governance?”

34. Patricia M. Dechow, Richard G. Sloan, and Amy P. Sweeney, “Detecting Earnings Management,” Accounting Review 70 (1995): 193–225. Also see Jennifer J. Jones, “Earnings Management during Import Relief Investigations,” Journal of Accounting Research 29 (1991): 193–228.

35. Other ratios in the analysis were not shown to have predictive power. These included leverage growth, the rate of change in depreciation, and changes in SG&A as a percent of sales. See Messod D. Beneish, “The Detection of Earnings Manipulation,” Financial Analysts Journal 55 (1999): 24–36.

36. GMI Ratings, “The GMI Ratings AGR Model: Measuring Accounting and Governance Risk in Public Corporations” (2013). Accessed February 26, 2015. See http://www3.gmiratings.com.

37. Richard A. Price, Nathan Y. Sharp, and David A. Wood, “Detecting and Predicting Accounting Irregularities: A Comparison of Commercial and Academic Risk Measures,” Accounting Horizons 25 (2011): 755–780.

38. Correia (2014).

39. David F. Larcker and Anastasia A. Zakolyukina, “Detecting Deceptive Discussions in Conference Calls,” Journal of Accounting Research 50 (2012): 495–540.

40. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, “PCAOB Staff Audit Practice Alert No. 3, Audit Considerations in the Current Economic Environment” (December 5, 2008). Accessed March 5, 2009. See http://pcaobus.org/Standards/QandA/12-05-2008_APA_3.pdf.

41. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), Overview of Summary Fraud Conference “Fraud . . . Can Audit Committees Really Make a Difference?” (New York, 2006).

42. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), Statements on Auditing Standards: SAS No. 99, AU §316.02 Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. (New York).

43. Still, many feel that the auditor should have greater accountability for rooting out fraud, and shareholder groups continue to press for liability. See Ian Fraser, “Holding the Auditors Accountable for Missing Corporate Fraud,” QFinance blog (September 22, 2010). Accessed November 13, 2010. See www.qfinance.com/blogs/ian-fraser/2010/09/22/holding-the-auditors-accountable-for-missing-corporate-fraud-auditor-liability.

44. Management, too, is required to produce an “internal controls report,” which establishes that adequate internal controls are in place.

45. Audit Analytics, “404 Dashboard: Year 6 Update, October” (2010). Accessed March 23, 2015. See http://www.auditanalytics.com/0002/view-custom-reports.php?report=cb248e6c34bc3e56c51aad7fb8e50c99.

46. Standard & Poor’s Compustat data for fiscal years ending May 2009 to May 2014.

47. Audit Analytics, “Analysis of Audit Fees by Industry Sector” (January 7, 2014). Accessed April 17, 2015. See http://www.auditanalytics.com/blog/analysis-of-audit-fees-by-industry-sector/.

48. Jonathan Weil, “HealthSouth Becomes Subject of a Congressional Probe,” Wall Street Journal (April 23, 2003, Eastern edition): C.1.

49. Jonathan Weil and Cassell Bryan-Low, “Questioning the Books: Audit Committee Met Only Once During 2001,” Wall Street Journal (March 21, 2003, Eastern edition): A.2.

50. Aaron Beam and Chris Warner, HealthSouth: The Wagon to Disaster (Fairhope, Ala.: Wagon Publishing, 2009).

51. Jonathan Weil, “Accounting Scheme Was Straightforward but Hard to Detect,” Wall Street Journal (March 20, 2003, Eastern edition): C.1.

52. Carrick Mollenkamp, “HealthSouth Figure Avoids Prison,” Wall Street Journal (June 2, 2004, Eastern edition): A.2.

53. Carrick Mollenkamp and Ann Davis, “HealthSouth Ex-CFO Helps Suit,” Wall Street Journal (July 26, 2004, Eastern edition): C.1.

54. SCAC, “HealthSouth Corporation: Stockholder and Bondholder Litigation,” Stanford Law School, Securities Class Action Clearinghouse in cooperation with Cornerstone Research. Accessed April 14, 2015. See http://securities.stanford.edu/filings-case.html?id=100835.

55. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Audits of Public Companies: Continued Concentration in Audit Market for Large Public Companies Does Not Call for Immediate Action: Report to Congressional Addressees,” Report no. GAO-08-163 (January 2008). Accessed May 20, 2010. See www.gao.gov/new.items/d08163.pdf.

56. These break down as follows: Deloitte ($1.1 billion), Ernst & Young ($2.6 billion), KPMG ($1.5 billion), and PricewaterhouseCoopers ($1.0 billion). In addition, Arthur Andersen paid settlements of $0.7 billion before ultimately dissolving following the Enron scandal. See Mark Cheffers and Robert Kueppers, “Audit Analytics: Accountants Professional Liability Scorecards and Commentary,” paper presented at the ALI CLE Accountants’ Liability Conference (September 11–12, 2014).

57. In the United States, each of the Big Four is organized as a partnership, owned by the partners who run the firm. Each partnership is overseen by a governing board, which numbers approximately 20 directors, the majority of whom are certified public accountants.

58. However, plaintiffs’ lawyers have attempted to name the international office in liability lawsuits. In 2004, Parmalat shareholders named Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (the international association) along with Deloitte’s Italian office, in a lawsuit alleging that the auditors were liable for failing to detect or report management fraud. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu asked a U.S. District Court judge to remove its name from the case, claiming that it is a legally separate entity and provides no services to the local office. In a 2009 ruling, the judge ruled that the international association should remain defendants. He cited the marketing, financial, and quality control ties that the international association provided to the local office as evidence that a substantial connection exists between the entities. According to Stanford Law School professor and former SEC commissioner Joseph A. Grundfest: “All of them have structures designed to build fire walls [between the local office and the international association]. The question is, will the dikes hold when you have this kind of a flood?” See Nanette Byrnes, “Audit Firms’ Global Ambitions Come Home to Roost,” BusinessWeek Online (February 3, 2009). Accessed November 13, 2010. See http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=36427167&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Also see Securities Class Action Clearinghouse, “Case Summary Parmalat Finanziaria, SpA. Securities Litigation,” Rock Center for Corporate Governance and Cornerstone Research. Accessed April 10, 2015. See http://securities.stanford.edu/filings-case.html?id=102961.

59. U.S. Government Accountability Office (2008).

60. Zoe-Vonna Palmrose, “An Analysis of Auditor Litigation and Audit Service Quality,” The Accounting Review 63 (1988): 55–73; and Inder K. Khurana and K. K. Raman, “Litigation Risk and the Financial Reporting Credibility of Big 4 versus Non-Big 4 Audits: Evidence from Anglo-American Countries,” Accounting Review 79 (2004): 473–495.

61. Alastair Lawrence, Miguel Minutti-Meza, and Ping Zhang, “Can Big 4 versus Non-Big 4 Differences in Audit-Quality Proxies Be Attributed to Client Characteristics?” Accounting Review 86 (2011): 259–286.

62. Public Oversight Board, “The Road to Reform—A White Paper from the Public Oversight Board on Legislation to Create a New Private-Sector Regulatory Structure for the Accounting Profession” (March 19, 2002). Accessed November 13, 2010. See www.publicoversightboard.org/White_Pa.pdf.

63. Jerry Wegman, “Government Regulation of Accountants: The PCAOB Enforcement Process,” Journal of Legal, Ethical, and Regulatory Issues 11 (2008): 75–94.

64. Louis Grumet, “Standards Setting at the Crossroads,” The CPA Journal (July 1, 2003). Accessed November 13, 2010. See www.nysscpa.org/cpajournal/2003/0703/nv/nv2.htm.

65. Larcker and Richardson (2004) found that, for the subset of firms that have apparent accounting deficiencies, the problem is weak governance systems (such as low institutional holdings and higher insider holdings) rather than payments made to the auditor for nonaudit services. See Roberta Romano, “The Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the Making of Quack Corporate Governance,” Yale Law Review 114 (2005): 1521–1612. Also see David F. Larcker and Scott A. Richardson, “Fees Paid to Audit Firms, Accrual Choices, and Corporate Governance,” Journal of Accounting Research 42 (2004): 625–658.

66. That study is Richard M. Frankel, Marilyn F. Johnson, and Karen K. Nelson, “The Relation between Auditors’ Fee for Nonaudit Services and Earnings Management,” Accounting Review 77 (2002): 71–105.

67. Romano (2005) is referring to restrictions including audit committee independence, limits on corporate loans to executives, and executive certification of the financial statements.

68. Mark Cheffers and Don Whalen, “Audit Fees and Nonaudit Fees: A Seven-Year Trend,” Audit Analytics (March 2010): 1–12.

69. Michael W. Maher and Dan Weiss, “Costs of Complying with SOX—Measurement, Variation, and Investors’ Anticipation,” Social Science Research Network (October 29, 2010). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1699828.

70. Grant Thornton LLP, “Chief Audit Executive Survey 2014: Adding Internal Audit Value, Strategically Leveraging Compliance Activities” (2014). Accessed February 26, 2015. See https://www.grantthornton.com/~/media/content-page-files/advisory/pdfs/2014/bas-cae-survey-final.ashx.

71. Cindy R. Alexander, Scott W. Bauguess, Gennaro Bernile, Yoon-Ho Alex Lee, and Jennifer Marietta-Westberg, “Economic Effects of SOX Section 404 Compliance: A Corporate Insider Perspective,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2013): 267–290.

72. John C. Coates and Suraj Srinivasan, “SOX after Ten Years: A Multidisciplinary Review,” Accounting Horizons 28 (2014): 627–671.

73. Measured in terms of abnormal accruals. See Thomas D. Dowdell and Jagan Krishnan, “Former Audit Firm Personnel as CFOs: Effect on Earnings Management,” Canadian Accounting Perspectives 3 (2004): 117–142. Beasley, Carcello, and Hermanson (2000) found that 11 percent of financial restatements due to fraud involved a CFO who had previously been employed at the company’s audit firm. However, the authors do not provide descriptive statistics to determine whether this represents an above-average incidence rate. See Mark S. Beasley, Joseph Y. Carcello, and Dana R. Hermanson, “Should You Offer a Job to Your External Auditor?” Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 11 (2000): 35–42.

74. Marshall A. Geiger, David S. North, and Brendan T. O’Connell, “The Auditor-to-Client Revolving Door and Earnings Management,” Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 20 (2005): 1–26.

75. The SEC audit review partner (or “concurring reviewer”) also rotates every five years.

76. Mara Cameran, Emilia Merlotti, and Dino Di Vincenzo, “The Audit Firm Rotation Rule: A Review of the Literature,” SDA Bocconi research paper, Social Science Research Network (September 2005). Accessed February 20, 2009. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=825404.

77. The authors reviewed 34 “academic” studies, 25 of which were based on empirical data and 9 of which were opinion based. Although the authors considered all 34 to be academic studies, we refer only to the 25 empirical studies here because the others did not test their conclusions against observable evidence. Interestingly, the authors noted that although 76 percent of the empirical studies concluded against mandatory auditor rotation, only 56 percent of the opinion-based reports opposed the practice. This is consistent with a general bias among thought leaders who advocate a best practice without regard to rigorous evidence.

78. For example, in 2008, there were approximately 50 audit firm changes among companies that use Big Four or other national accounting firms. Among all publicly traded companies, there are approximately 1,000 auditor changes each year. Audit Analytics, “Where the Audit Gains & Losses Came From: January 1, 2008–December 31, 2008” (2009). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.auditanalytics.com/doc/CY_2008_WhereTheyWent_1-12-09.pdf. Also see Lynn E. Turner, Jason P. Williams, and Thomas R. Weirich, “An Inside Look at Auditor Changes,” The CPA Journal (2005): 12–21.

79. “Standard Instructions for Filing Forms under the Securities Act of 1933, Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 Regulation S-K,” Cornell University Law School. Accessed April 10, 2015. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/part-229.

80. Susan Zhan Shu, “Auditor Resignations: Clientele Effects and Legal Liability,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 29 (2000): 173–205.

81. J. Scott Whisenant, Srinivasan Sankaraguruswamy, and K. Raghunandan, “Market Reactions to Disclosure of Reportable Events,” Auditing 22 (2003): 181–194.