Chapter Twenty-Nine. The Creative Craft

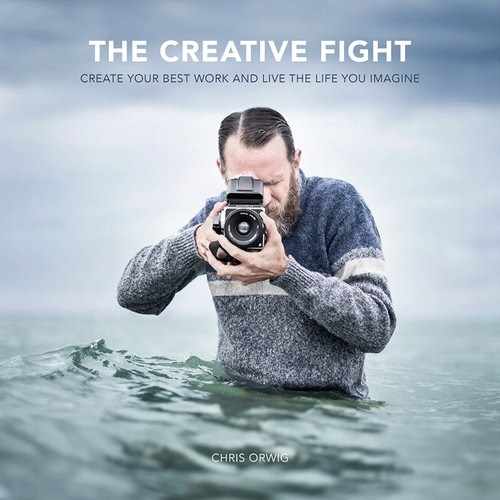

When it comes to improving your craft, shortcuts rarely work. One of the most common—and misguided—photography shortcuts is to buy more expensive gear. But gear does little to improve the quality of one’s work. Another misleading tip is this: “To take better photographs, you need to stand in front of more interesting things.” Yet it’s not what you photograph, but how. Good images come from within. Buying a nice camera and visiting a beautiful place is easy; making meaningful photographs is hard.

After teaching at a photography school for 12 years, I could easily spot the students who would succeed. Those who relied on tips and tricks didn’t get far. The ones who avoided the shortcuts were the ones who thrived. This is true for any craft. You can’t cut corners if you want to gain skill.

The Siren’s Call

The problem with most shortcuts is the way they entice. The time-saving advice initially rings true. That’s because most shortcuts are half-truths that have been bent into an odd form. For instance, take the one about creating better photographs by standing in front of more interesting things. Of course it’s important to consider what you shoot—subject matter is critical. Of course it’s helpful to photograph a beautiful place. Yet more interesting subjects won’t necessarily improve your craft. Often the more impressive and beautiful the subject matter is, the worse the frames. And over the last dozen years, I watched as many of my students visited far-off lands or hired expensive models only to return with disappointing and mediocre photographs of fascinating things.

The excitement of photographing an impressive person or a stunning scene can lead to weak photographs. The singer and songwriter Marcus Mumford said it this way: “Don’t tell me that I am fine. When I lose my head, I lose my spine.” And making photographs without a strong backbone doesn’t turn out very well. The photographer who wants to create meaningful photographs must keep her head. She must guard against being overwhelmed and bring her own voice to the scene. Without a strong point of view, the photographs will fail.

Without a clear vision and voice, the best gear and the most stunning subject can’t help. As Ansel Adams famously put it, “There is nothing worse than a sharp picture of a fuzzy idea.” Good pictures come less from the subject and scene and more from strong ideas.

Seeing the Unseen

The surest way to come up with better ideas is to nurture a curious and imaginative approach. Curiosity helps us to look at the typical and to see something that was previously unseen. And imagination is curiosity set ablaze. Imagination is the art of seeing beyond the surface of things. Those who imagine see what isn’t visible to the eyes—sometimes an outlandish idea and other times an undercurrent. The best writers, poets, filmmakers, photographers, architects, artists, and so on constantly look for hidden truths. When you look at the world through the imagination’s eye, you begin to see the invisible pulse that was previously ignored.

While studying in Spain, I signed up for a college art history course at the Museo del Prado in Madrid. Each week the class met in front of a painting. With notebooks in hand, we stood in awe as our teacher gave us insight into why these masterpieces hung on these walls.

I liked to arrive early in order to view the paintings before the lecture began. In those moments, I tried to appreciate what I saw, but these world-famous paintings just looked kind of dull. Then when our teacher arrived, she revealed the mysteries that made these paintings so profound. She helped us embrace the secret truth hidden within the frame. By the end of the lecture, the connection we felt with the paintings was deep. After a few months, I realized that our art teacher wasn’t just teaching us about a specific piece; she was teaching us how to be curious, how to imagine, and, ultimately, how to see.

This experience taught me the value of looking deep. I came to appreciate the mystery of art. The paintings of Rembrandt, for example, seemed to reveal ideas that could not be conveyed in words.

Mystery ignites the imagination. That’s why the best photographs, songs, paintings, and movies are the ones we can’t quite figure out at first. They are subtle, less obvious, and sometimes incomplete. They tell us enough but not too much, engaging the imagination and inviting the viewer to complete the idea. Such imagination is like dreaming while you are awake. And this practice isn’t just for kids who are bored in school. It’s a worthwhile pursuit for all of us who wish to lead better lives.

THOSE WHO DREAM BY DAY ARE COGNIZANT OF THINGS WHICH ESCAPE THOSE WHO ONLY DREAM BY NIGHT.

— EDGAR ALLAN POE

Clouds and Rain

Imagination is often visually represented as a cloud. Bright and white. Ethereal and odd shaped. Imperfect yet ideal. Temporal but real. Yet imagination isn’t just floating in the sky. Imagination is learning to find the invisible dots that, when connected, create a discernible line. Buddhist philosophy illuminates this idea in a poetic way. As one traditional saying goes, “We must learn to see the cloud in the tree.” At first blush, this sounds like an unintelligible sentence made up of two seemingly unrelated things. But when we look closer, a connection forms. Without the cloud there is no rain. Without rain, the tree cannot grow.

Imagination helps us see hidden connections between clouds and trees and between life and death.

In Jack London’s gripping story “To Build a Fire,” the protagonist sets out to cross the Yukon wilderness on a frigid and sunless day. The deep snow and subzero conditions are par for the course. But early in the story, London foreshadows doom: “The trouble with [the main character] was that he was without imagination. He was quick and alert in the things of life but only in the things and not their significance.” Ultimately, it is his lack of imagination that leads to his demise.

Imagination helps us conjure up a vision of the icy river under the snow or the life force that flows through a tree. Imagination is the art of seeing beyond the shell. The painter Diego Velázquez, whom I studied in Madrid, was a master in this approach.

I AM CERTAIN OF NOTHING BUT THE HOLINESS OF THE HEART’S AFFECTIONS AND THE TRUTH OF THE IMAGINATION.

— JOHN KEATS

ONE’S DESTINATION IS NEVER A PLACE, BUT A NEW WAY OF SEEING THINGS.

— HENRY MILLER

Humanity

During a time when canvas and paint was precious, Velázquez did not let his gear go to his head. Nor did he let his position squelch his inner voice. As the painter for the Spanish royal family, Velázquez’s work was not flattery but true. In an era of idealism, Velázquez painted people with authentic respect. Velázquez didn’t typecast; he painted the hidden humanity underneath the shell.

Rather than paint an idyllic king, he depicted a real man whose countenance engendered sympathy, pity, and respect. When painting dwarfs (as they were called then), it wasn’t to belittle or make fun. In such portraits we see wisdom, caring, and courage. While others saw an arrogant king, ugly daughter, humorous jester, or misshapen body to laugh at, Velázquez saw deep into the humanity that connects us all.

If there is a secret to creating better art, it isn’t to buy new gear or to stand in front of better things. If you want to make more interesting photographs, become a more interesting person yourself. Follow Henry Miller’s advice: “Develop an interest in life as you see it; the people, things, literature, music—the world is so rich, simply throbbing with rich treasures, beautiful souls, and interesting people.” And when working with a subject that may not have an ideal look, it’s your job to find the humanity within.

The most ordinary person is the greatest subject of all, not the other way around. The arts are about finding that kernel of beauty or truth that is hidden inside. For such endeavors, you can’t rely on your eyes. Imagination is the only way to find invisible things.

Exercise

STEP 1

Visit an art museum with the intent of “seeing the cloud in the tree.” Look for the invisible dots that connect, and strive to discover the mystery behind a piece. If it isn’t readily apparent, talk to a docent or read something online. And let your imagination out of its cage. Enjoy the art for the way it makes you feel and for the thoughts it generates.

STEP 2

Create your own art that speaks in a less direct way. Rather than taking a typical portrait, have someone hold something that blocks part of his or her face. Or compose the image so that we can’t see the whole scene. Rather than making literal photographs, make photographs that show us what we have overlooked.