Chapter Thirteen. The Creative Flow

Getting a part-time teaching job at a world-class photography school was a dream come true. I couldn’t have imagined a better career shift. So I threw myself into the work and followed W. B. Yeats’s advice, “Education isn’t filling a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” For twelve years my job was to ignite, empower, and help aspiring photographers achieve their dreams. Yet the path to becoming a photographer isn’t easy, so the difficulty of my classes and our program reflected the challenge ahead. Not every student graduated; fewer went on to thrive. Those who found success did so in an impressive way—it was the world of sink or swim. Throughout it all, I was always keen to pick up on the clues that shed light on why some students excelled while others failed. After a few years, the telltale indicators became clear.

Why Students Succeed

I quickly discovered that the successful students were a tenacious and driven bunch. They were voraciously creative and surprisingly well composed, even in the face of great challenge. No matter what you threw at them, they wouldn’t flinch. When a student stumbled and fell, she picked herself up and tried again.

Two of the most telling signs of a student’s potential were how much effort they put in and how they handled critique. After finishing an assignment, the student presented it to the teacher and class for evaluation and review. Regardless of the quality of the work, it is always nerve-racking to have your work evaluated in front of a group. The students who eventually went on to thrive had nerves of steel. This gave them the ability to hear and receive the feedback without being crushed. The best students took it all with a grain of salt but always listened so that they could improve. The worst students were defensive, gave excuses, or just ignored the advice. I came to learn a lot about my students and myself during those times of critique. The most important lesson I learned came as a complete surprise.

Critique and the Boomerang Effect

The value in critiquing someone else’s work is that it makes you think about your own. One day as I evaluated some stellar upper-division student work, it struck me that their photographs were better than my own. Yet how could this be? After all, I was a successful commercial photographer and I had written two best-selling photography books. But truth be told, my current work wasn’t up to par, and in photography you can’t rest on the success of your past. Somewhere along the way I had stopped practicing what I preached, and it was as if I had become like the proverbial cobbler whose kids didn’t have any shoes. I had become a cliché. It was time to make a change. I had been thinking about leaving my teaching post for a few years, and this particular realization gave me the final nudge.

The ivory tower is a comfortable place, but it is isolating as well. So I traded in my professorial robes for street clothes. I left the benefits and comforts of the job in order to refine my craft and strengthen my core. Rather than critiquing others, I needed to get some critique myself. So I signed up for a workshop in New York and showed up like an eager new student on the first day of school. The workshop was a wealth of learning opportunities—lectures, conversations, capturing photographs, and portfolio reviews. Eventually, it was my turn to present a portfolio of my work. I was on the chopping block and I was scared.

Confronting Fear

Neurologists tell us that when we are afraid, the area of our brain called the amygdala lights up. The amygdala is known as the primitive or prehistoric part of the brain. It controls our fight or flight response and is often referred to as the “lizard brain,” because it’s the part of the brain that is reactive and focused on core survival needs. Thought leader Seth Godin describes the lizard brain as horny, hungry, and scared. As Godin explains, it’s this part of the brain that’s responsible for fear, anger, and sex, and it cares what everyone else thinks. The lizard brain regulates fear and is often to blame for our resistance to risk-taking. For us photographers, it’s the lizard brain that prevents us from having courage to show and to create our best work.

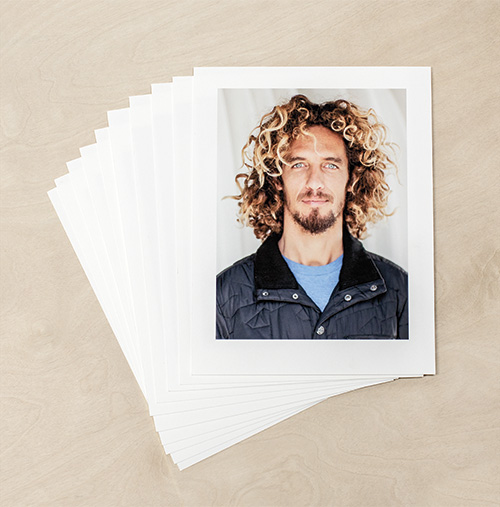

As I opened up my box of portfolio prints, my amygdala was flashing red. I felt like a lizard who wanted to run and hide. The workshop instructor started to review and critique my work. I braced myself. He said, “When I look at these photographs I think, ‘This photographer is good,’ but then at second glance, maybe not. You have a great connection with your subjects in these portraits. I can tell you are committed to the subject... but you aren’t committed to the frame. By neglecting the frame, you are letting your subject down.” These words burned, but at the same time brought relief.

The workshop instructor was a friend and mentor who I know had my best interests in mind. And he had pinpointed my Achilles heel. It took him just a moment to find the flaw that I knew was there but didn’t know how to describe. In essence, his critique pointed out a need to refine my composition skills. And he was right, I wasn’t using the frame very well. Yet in the moment, I felt small, like a small lizard sitting on a rock as a predator soared above. I wasn’t sure if I should bask in the sun or run and hide. Then as the critique progressed, the predator attacked and grabbed ahold of my tail.

TO BE YOURSELF IN A WORLD THAT IS CONSTANTLY TRYING TO MAKE YOU SOMETHING ELSE IS THE GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT.

— RALPH WALDO EMERSON

When caught by its tail, a lizard has the ability to detach so it can escape. The scientific name for this defensive skill is “autonomy.” Autonomy is what got me into this mess and I needed to find a new strategy to get me out. After all, I was a self-taught photographer who had come a long way. I was a self-made man and a teacher who stood apart from the crowd. Yet there was my flaw, as greatness rarely shines without the help of someone else.

I thought back to my top-performing students and their unwillingness to give up. These students were open to criticism and constantly sought outside help. It was my turn to follow their lead. The workshop was a good first step, but still I was desperate to find a new paradigm for understanding my identity, work, and life.

Identity and Creative Flow

A few months later, I found some wisdom from an unlikely source while talking with surf legend Kelly Slater. Over dinner we chatted about photography, identity, and life. While Slater may be the quintessential example of cool, in person he is truly a humble and down-to-earth guy. At one point he said, “Chris, I’m embarrassed to admit that for much of my life I didn’t realize the difference between the idea of Kelly Slater and the person of Kelly Slater. And because of that I made a lot of mistakes.”

Hearing Slater talk about his struggles shed some light on my own. I realized that I had confused the idea of Chris Orwig with a more authentic version of myself. It hit me that the effort of trying to maintain this act was keeping me from contributing in the greatest way possible. It was like discovering that I had been driving around in my car with the emergency brake on. Once released, I was free to be true to myself, and my creativity began to flow in a powerful and unprecedented way.

Creativity always flows the fastest when we are the honest and authentic versions of ourselves. Trying to be someone else will only restrict and impede. Letting go of that begins with a realization that you are 100% unique, and that the more uniqueness in your work, the better it will be.

To begin the process of becoming true to ourselves, it helps to answer a few questions about your life: What makes you unique? What makes you come alive? What dreams and ideas course through your veins?

When asked if writing was hard, Ernest Hemingway replied, “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” When you read one of his books you can feel the lifeblood in his words. We need more of this in whatever work it is that we do. There is a creative spark hidden deep within the cellular level of your true self. Your job is to find that source and let it flow.

STEP 1

Get out a journal and take a few minutes to write out answers to the following questions:

What makes you unique? What makes you come alive? What courses through your veins?

STEP 2

Like a fish trying to describe water, sometimes it is difficult to identify our own strengths. So find a friend, colleague, or mentor and ask them to help. Ask for their insight into what makes you unique. Ask for their opinion of what strengths set you apart from the crowd.